Stranger Things and Nostalgia Now

Edited by Joel Burges and Jason Middleton

Introduction

1

After a game of Dungeons and Dragons, two boys bike home from their friend's house on a night in 1983. They are unaware of the awful and awesome events about to envelop their childhoods. Ignorant of this impending horror, one boy boyishly challenges the other to a race. The prize will be any issue of a comic the winner wants from the collection of the loser. Moments later, the winner emerges. Will has defeated Dustin. He lays claim to his reward: "I'll take your X-Men #134!"

Readers likely recognize the race between Will and Dustin as a scene from the opening sequence of the acclaimed Netflix series Stranger Things. What readers might not recognize is the obscure X-Men reference. But both of us did, right away. Both of us immediately knew — though maybe Jason faster than Joel — that this was a reference to the 1980 issue of X-Men in which the red-headed good girl Jean Grey, telekinetic and telepathic, turns into Dark Phoenix. Stranger Things traffics in just these kinds of references, both obscure and obvious, at length. It does so to the point of traffic jam, in fact. Within the first five minutes of the episode — even before the X-Men reference — we get the Dungeon and Dragons gameplay among four boys, the poster for John Carpenter's The Thing in the background, along with elements of mise-en-scène such as wood paneling, banana-seat bikes, and a Mitsubishi television set complete with rabbit ears. These nerdy period details reconstruct the '80s for us not only affectionately and viscerally, but also studiously and meticulously. They bring us close and keep us far. Their intimacy turns on how the sheer plenitude of detail evokes the past for spectators in a way that also turns on our distance in time from that past, with the details accumulating in the present to produce an image of the 1980s far more difficult to achieve when we were actually living through the decade.1

This intimacy and distance is necessary if such a high-production exercise in consumer nostalgia is to succeed — clearly an aspiration of the Netflix business plan. Nostalgia rises and falls on the accumulation of these kinds of references and details, on their build up as so much stuff that lets us feel our way, not into the 1980s, but into something more aesthetic and atmospheric: the '80s. This is why it doesn't matter whether you get every reference. Stranger Things is invested in a phenomenology of the '80s more than a representation of the 1980s. Every detail is chosen with a phenomenological care that verges on fetishism. But this atmosphere of aesthetic fetishism doesn't mean that each detail, each reference, isn't meaningful. Meaning emerges in the fractures that this fetish invokes. Those fractures are subjective ones in the personal experience of boyhood that the '80s of Stranger Things recalls for each of us from the 1980s.

Boyhood in the 1980s was a broken experience for both of us. We were two boys, girly and nerdy in turn. We were two boys, not only not identifying with being a boy in some normatively athletic way apt to gym class, not only alienated by the boy's body Presidential Fitness Tests were supposed to engender, but also caught up in a non-identification with a wider world that organized what it was like to be a boy in the first place. It is this fracture — this non-identification — that Stranger Things contains within itself and opens up for us, granting it a historicity such nostalgic objects are typically said to lack precisely because some vision of the '80s overtakes the lived experience of the 1980s. For us, then, the reference to X-Men #134 possesses this historicity because it, more than many of the other details, opens up the fractures around what it means for each of us to have been a boy in the 1980s; what it means to take up the 1980s and the '80s as a shared object of study in the 2010s; and the intellectual intimacies enabled by our fractured experience of the 1980s and our dialogic return to it in a cluster of essays, with our contributors, on the cusp the arrival of Stranger Things Season Three. So let us linger over X-Men #134 by way of introducing our investments in this cluster. There we find Jean Grey-cum-Dark Phoenix, a figure with whom neither of us shares a gender, but around whom something shared about the 1980s and the '80 continues to play out to this day.

2: Jason

The issues that comprise the Dark Phoenix story narrate how radically heightened power corrupts Jean — original team member of the X-Men, protégé of team patriarch Professor Charles Xavier, lover to both team leader Scott Summers (Cyclops) and fan favorite Wolverine. Possessed by a cosmic force called The Phoenix, Jean's telekinetic mutant powers are steadily amplified to god-like proportions. Jean becomes Phoenix, and Phoenix becomes Dark Phoenix when she lashes out violently against the mind control spell of an evil adversary of the X-Men. Her rage culminates in the annihilation of a civilized planet in a distant galaxy, for which she is called to account by an intergalactic governing council led by Empress Lilandra. In issue 137, Jean takes her own life in battle rather than risk causing further destruction.2

This is widely regarded as the most tragic death in Marvel Comics.3 For me, as a nine-year-old reader (the age Will and the others would have been when this issue was published), Grey's death produced a melancholia tied to the urge to displace the painful experience of the character's loss through the endlessly expansive act of reading enabled by the comics medium and the magnitude of its narratives. I understood only later how this pleasurable sorrow, a mostly solitary experience of my boyhood, intimated the larger collective melancholy that joined fans and creators in a kind of repetition compulsion. The bounded continuity system of the comics of that period proved inadequate to the traumatic rupture of Grey's death, and she was subsequently resurrected and killed repeatedly, across proliferating timelines in the comics and now in the movies. This summer's Dark Phoenix (Simon Kinberg, 2019) is charged not only with translating the story to cinema, but also with providing closure and redress for fans outraged by Ratner's roundly disparaged attempt to do so in X-Men: The Last Stand.

In an article that begins in much the same place Joel and I have, Alex Abad-Santos has detailed the many nods in Stranger Things to the Dark Phoenix saga and the parallels between Jean/Phoenix and the show's telekinetic heroine, Eleven, though he maintains that "the X-Men saga spins out into a tale of planetary destruction, punishment, and love. Stranger Things feels more intimate, more about childhood and the loss of it."4 For me, though, the Dark Phoenix story stands as the zenith of a form of reading, a relationship to a text, inextricable from "childhood and the loss of it." Becoming a teenager meant leaving comic books behind in favor of serious books, redoubling the melancholy of Jean's death with the loss of a medium in which she was always the strongest point of diegetic attachment. Why? Because the Dark Phoenix saga felt adult to me in a way that I couldn't fully comprehend as a kid, but which set it apart not only from the other comics I had obsessively read and collected but also from the literary story worlds to which I was most strongly attached — Middle-earth, Narnia, Prydain.

This adultness is due in part to the story's admirably rendered moral ambiguity. There are villains that contribute to the rise of Dark Phoenix, but in the final chapter (#137) there are really no good guys or bad guys, just a group of well-meaning characters drawn into a battle over the fate of Jean/Phoenix, with both sides plagued by emotional and ethical conflicts and unsure of the justness of their respective positions. Tolkien and Lewis gave us some characters with flaws and complexities, to be sure, but there were always greater powers of darkness that should, and could, be defeated for the happy endings. No possible outcome of the Dark Phoenix story could have been described as happy. In this way, the story fractured my expectations of narrative itself, and of the always-consolatory power of reading for a socially unskilled kid. It pulled me out of the reassurance and safety that the fantastic realms of literature for children had always offered, intimating an adult world of choices and regrets that childhood as I'd known it could not contain.

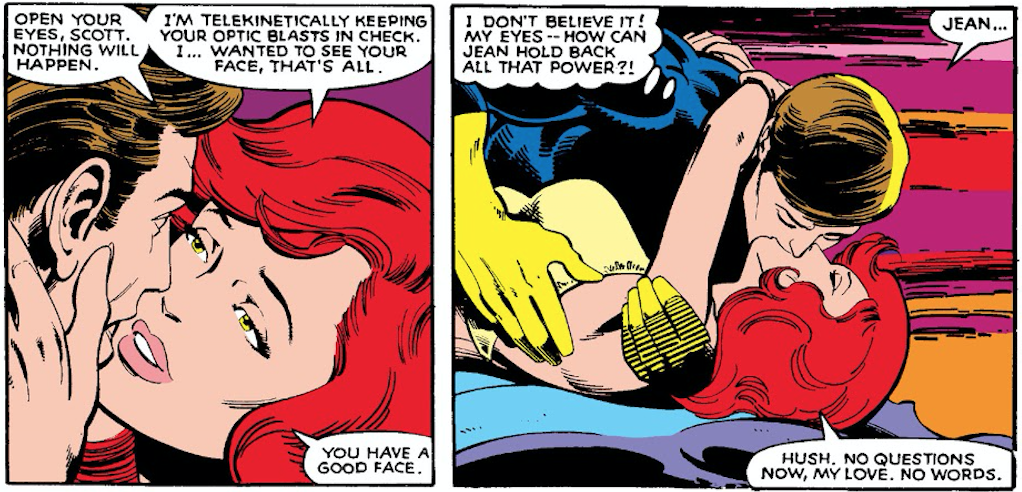

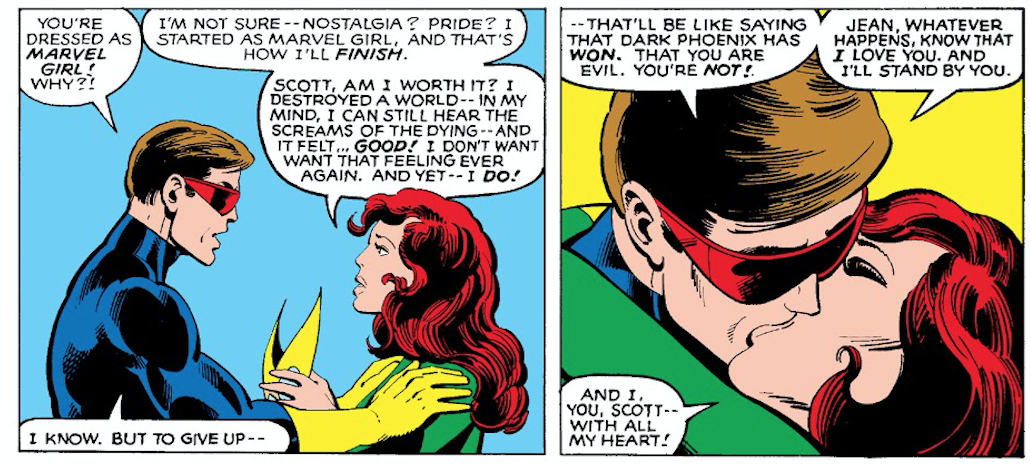

Frodo, Lucy, Taran: the protagonists of classic children's fantasy literature are youthful, often children themselves. Even as some of these characters aged, romantic love was sidelined entirely (Frodo) or present in only the most ritualized way (Taran). Not so with the Dark Phoenix saga. Sex permeates the story, from the romance-novel tableau and dialogue of issue 132, in which an increasingly powerful Jean seduces Scott on an isolated cliff top beneath a sunset ("Hush. No questions now, my love. No words."), to the dominatrix-style outfit Jean subsequently wears when brainwashed to be the "Black Queen" of the decadent Hellfire Club, the persona that precipitates her conversion to Dark Phoenix.

Alternately ennobling or corrupting, adult sexuality is inextricable from the story and the ultimately tragic changes it brings to long-familiar characters. For all of its science fiction elements and superheroics, the Dark Phoenix saga is at its core a tragic love story. There is no kingdom to be saved, no ring to be destroyed, in the later issues of the saga not even a villain to defeat. The central conflict of the story is whether Jean's soul will survive its possession by the Phoenix, so that she may complete her heterosexual coupling with Scott. The penultimate chapter, issue 136, offers the deceptive resolution of a marriage proposal; the final chapter ends with Jean's self-sacrificial death. As Jean's more modest telekinetic powers as Marvel Girl were to the longstanding, angsty teenage crush between her and Scott, so are her increasingly god-like powers as Phoenix to the passionate and terrifying adult love affair whose course is run in the Dark Phoenix saga. Just before the climactic battle of issue #137, the couple even names the nostalgia they feel for their own youth, as they face down adult consequences and the prospect that it may simply be too late for a happily ever after.

The story of Dark Phoenix unsettled both my expectations for narratives in which good is distinguishable from bad and always wins in the end, and for identifications with characters whose inner lives were readily imaginable from my juvenile point of view. And it made adult heterosexuality — something foreign to the inner lives of Frodo et al., and to my own — suddenly legible, and desirable, in an equally unsettling way. The superheroes whose identity as teenagers had always been central to Marvel's marketing made a transition to adulthood that was amorously thrilling for them and for me as a child reader, but also marked by loss and grief. Before this, there was no difference for me between wanting to be Frodo or Lucy. I think I still wanted to be both Scott and Jean. But this story opened a window to that place where to be conflicts with to have. Judith Butler shows us how a boy's repudiation of the feminine "reconstructs it in difference from the self as the object of desire" and forecloses same-sex desire. The ego assumes a gendered character, in other words, through an "ungrieved and ungrievable" loss, a preserved, melancholic identification with the repudiated feminine.5 I was no longer a child, but a boy, though becoming a boy turned on a melancholic break with both femininity and homosexuality. In this way, I can better understand the pervasive melancholy I felt over the character's death, which led me at that point to narratively regress through the back catalog of X-Men issues. My need to endlessly defer and displace the painful awareness of Jean's eventual death was also a readerly figuration of my own dawning awareness of adolescence and its gendered identifications, and of what would be lost in attempting, however awkwardly, to attain them.

3: Joel

My relationship with Jean Grey/Dark Phoenix works in reverse of Jason's since it is tied up with becoming a gay man who can't and won't repudiate the feminine. The red-headed female protagonist, as a type, has been a source of power for me since I was a boy in the 1980s, when I devoured L. Frank Baum's The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and the countless sequels to it, and when I immersed myself in L. M. Montgomery's Anne of Green Gables and its many sequels. (I recently noticed in re-watching Stranger Things that in a flashback in Season One, Sheriff Hopper is depicted reading Anne of Green Gables to his dying daughter.) My mother worried in this pre-pubescent period that I was reading too many books about girls, as if I were being feminized by what I wanted to read, as if my reading would encourage a femininity a boy isn't supposed to have. My mother's anxiety probably had as much to do with being a single parent of an only child as with any threat to my development as a boy. But maybe I was being feminized. Maybe I was reading for a particular form of femininity. Maybe I did want to be a girl in a world in which I often didn't feel like a boy, much less adequately read as a boy by the world around me.

More than Dorothy, Anne Shirley served as the basis for my fascination with the red-headed female protagonist: a fiery girl with a propensity to explode and who is fiercely smart. Despite the striking whiteness of this type, she is typically figured as an outsider who does not belong, a disruptive force to the world the text is making and unmaking, whether Oz or Avonlea. This characterization also features in three texts that I still love from my teenage years, when I was struggling with homosexual desires I didn't want to have. All are by Joyce Carol Oates. All of them put a red-headed girl or woman at their center. And all of them not only tend to characterize that girl or woman as preternaturally intelligent, but also possessed in a way, caught up in social transgressions that locate her on the margins of her time and place: interracial love (Because It Is Bitter, and Because It Is My Heart and I Lock My Door Upon Myself) and incestuous desire (You Must Remember This). But reversing Jason's course, it was as an adult — or at least a young adult in my twenties — that I discovered the story of Dark Phoenix and its resonances with Dorothy Gale, Anne Shirley, Iris Courtney, Edith Freilicht, and Enid Marie Stevick. In this, I was able to look back on the fractured boyhood of my 1980s when I wasn't repudiating the feminine adequately, thanks in large part to my emerging homosexuality.

I first discovered the story of Dark Phoenix by way of one of the campy cultural forms in which she recirculated in the 1990s and 2000s: Buffy the Vampire Slayer. One of the central characters of Buffy is Willow Rosenberg.

Willow is a nerdy redhead who, in Season Six, is compared to Dark Phoenix by one of the white male nerds whom she blames for her girlfriend's murder. This comparison occurs during a rampage in which, drawing on her massive well of Wicca power, Willow decides to destroy the world so as to end the pain of being human for everyone. The episodes portraying that rampage preceded the release of Bryan Singer's X-2: X-Men United by a year, followed by Ratner's X-Men: The Last Stand a few years later. However awful Ratner's rendering of the Dark Phoenix saga, the scenes of Famke Jannsen as Dark Phoenix in that film — especially the one in which she takes revenge on Professor X for containing the joy and rage of her power, a scene that alludes to The Wizard of Oz when Grey makes her childhood home float propulsively upwards in the sky as she unleashes on her mentor and captor — are excruciatingly moving, even mobilizing in how they show, as with Willow, her control of her intelligence give way to a resistance to control.

It was only after Buffy and these X-Men movies that I finally read the saga penned for the comics by Chris Claremont and illustrated by John Byrne.

Even as Jean/Phoenix has found another descendant in Eleven that I can identify as such, I am still working out why this fiery figure pulls me so. Being gay and becoming a gay man is involved in this pull, in the fantasies of power these girls and women generate. This pull doesn't feel like a simple identification with the female or feminine or feminist "within," though female firepower does have some elemental energy for me that I refuse to repudiate. If anything, the pull feels like a non-identification with a world that continues to organize my gender, race, sexuality, class. This is a world in which I have embraced masculine forms to deal with the world (weightlifting) and socially sanctioned ways of thinking to make sense of that world (scholarship). But sometimes what I want is to lose control, to let go — to just burn, and to burn it down.

This fiery desire tells me I want a new world that is currently a non-world. In that non-world, race, gender, sexuality, and class don't fracture us so violently and so ordinarily. There is a more nostalgic way to characterize this desire to be less fractured. For what the allusions to Jean/Phoenix on Stranger Things spark in me is nostalgia for a girlhood that I didn't — that I couldn't — have, but that I longed to inhabit, at least partially, in part because becoming a man was — and still often enough is — interrupted by being gay. My experience is not unlike what Eleven is working out in the first two seasons of Stranger Things: how to have the telekinetic and telepathic firepower she does, and how to be a girl. At the end of Season Two, that desire played out in disappointingly normative terms that, I worry, are about to get worse in Season Three. I would rather see Eleven allowed the burning brightness of being a girl with a firepower the world cannot refuse instead of yet another girl killed for having that power in the first place.

But I expect to be disappointed. After all, such disappointments abound in stories of women burning it down, the most recent being Daenyrus Targaryon's cataclysmic turn on the back of Drogon, the beautiful dragon with whom she becomes one in the penultimate episode of Game of Thrones, "The Bells," before being murdered in the final episode for her "mad" desire to break the wheel of power in the name of a new world.

As the conclusion of Game of Thrones suggests, female firepower is almost always both a narrative-psychological and ethical-political crisis. As such, it is often bound to disappoint, and bound as a result to engender the melancholic identification with the repudiated feminine that Jason tracks in his account. Like Jason, I am pulled toward Jean/Phoenix again and again. But I am equally pulled toward bro-like forms of masculinity in everyday routines of working out and being a gay man, in the name of possessing a muscular masculinity that feels less fractured than my boyhood self. I appear to be not only nostalgic for a girlhood I didn't have in the 1980s, but also longing for a masculinity that I'll never achieve, now or then.

An unachievable masculinity sometimes feels less fracturing than the non-identification with the world that Jean/Phoenix and her kin embody for me. But this masculinity lacks the burning desire for a blazing world that pulled — and still pulls — me to those girls and women in the first place. It lacks the incandescence that their femininity brilliantly concentrates. But there is, for me, something beyond melancholic identification in that incandescence worth trying to see: how the fantasy of female firepower might be turned into a powerful fact — one world destroyed and negated so that another can be forged and affirmed.

How to make the leap from a fantasy of world-making agency to a fact of world-changing agency, and the crises that leap will necessarily entail, is the ultimate problem of the non-identification with the world that fractured me as a boy during the 1980s in the first place.6

4

For both of us, then, Stranger Things did not activate the longing to return to a comfortingly idealized past. Instead, it sparked a reckoning with discomfiting but inspiringly unfinished senses of self in boyhoods respectively experienced as nerdy and girly — appellations powerfully pejorative in the 1980s, and preparing us to be the target of the word "fag," even though only one of us turned out gay. While it gives its characters a collective into which to retreat, Stranger Things is at pains to demonstrate this fractured sense of boyhood self through the portrayal of its protagonists as consistent objects of bullying. This is what we recall the most about being boys in the late twentieth century. What watching this obsessively visual and relentlessly sonic show about the '80s further recalls for us is what we were reading, viewing, and watching. We sought solace, coherency, and yet also volatile letting go in novels and comics and movies and TV.

For Ashley Reed, Stranger Things evokes the movies of her 1980s suburban girlhood (e.g., E.T., The Goonies, Poltergeist) and works to "repair [ . . . ] a gaping hole at the center of those movies: their inability, in films all about the wonders of childhood, to imagine the inner lives of girls."7 Stranger Things attempts this revisionist and restorative approach to its 1980s source material in a number of ways, treating the iconic '80s texts not as perfect models to be reproduced but as unfinished, as still in process. Our own first encounters with Stranger Things seemed to offer something different from other contemporary exercises in cultural nostalgia; in particular, with its fiery heroine, Eleven, the show does not try to clone the original Jean Grey, but instead to acknowledge her widespread and powerful presence in our pop cultural DNA. In doing so, the show may point less toward the melancholic pursuit of a lost object than toward the discovery of new objects and new attachments. Such objects and attachments are at stake in Amy Rust's essay on props and old and new media in this cluster. Eleven's twinned powers of telekinesis and telepathy, inherited directly from Jean Grey, instantiate for Rust the inseparability of analog media's immediacy and digital media's abstraction that stretches back at least to the 1980s of the show's setting, troubling the perception of analog media props as simple exemplars of nostalgia. Through Eleven's telepathy, and in spite of its own attachments to old media, the show suggests a form of "feeling at a distance" that points us away from the stock associations between new media and social isolation and control.

If nostalgia is about the painful longing for home, that home as reconstructed by Stranger Things is tensely twofold. It is a site of reparative return to autonomous childhood freedom, anachronistically made psychically safe by greater parental involvement (all of which Jason explores in his analysis of the generic convergences of Stranger Things in his essay for the cluster). But it is also reconstructed as an original time and space of repression and retreat, alienation and anger, in which the violence of masculinity and heterosexuality reigned. The '80s of Stranger Things is thus not as glossy as you might think. Its '80s are indelibly fractured, moving between reparation and alienation in a way that makes its image of that era more than the routinely invoked "nostalgia for the present" that Frederic Jameson once described as producing an unduly pretty picture of the past in the retro modes of postmodern commodity culture. Given that the nostalgia of the series is often crosscut with violence (as Joel explores in his essay for the cluster), history does indeed hurt on Stranger Things.8 The Duffer Brothers' series moves between the '80s it engenders as an aesthetic atmosphere, and the bad weather the 1980s stirs up in that atmosphere to this day. As a result, the series opens up in generative ways the problem that we have tried to identify in accounting for our distinct relationships to the Dark Phoenix saga: how to move beyond melancholic identifications that draw us back to the same texts and figures again and again, and thus how to make the leap from a fantasy of world-making agency to a fact of world-changing agency.

In raising the possibility of such a leap, which we doubt Stranger Things will (or even can) make, we are trying to avoid some of the pitfalls that emerged in the nostalgia of Season Two. The second season feels distinctly melancholic, as if the longer the series protracts its nostalgia, the more likely it is to get stuck on the '80s it so sensuously imagines, and so stall us in the historical experience of the 1980s it recalls rather than grounding us in the conditions of the contemporary. The danger is that this could lead us to ignore not only how the 1980s were fractured for us, but also how those fractures extend into the 2010s within the '80s that Stranger Things creates as its world. We want to remain tuned into how, for both us, the nostalgia of Stranger Things contains within it the fractured boyhood of feminine firepower and melancholic masculinity that our 1980s embodies for us as a little history, if you will, of the present in which we currently find ourselves. We hope this means, moreover, that both our fractured boyhoods and Stranger Things have something to tell us about nostalgia now, especially the degree to which the politics of nostalgia today simultaneously divide and unite us, with the fractures of the past resurfacing as the conflicts of the present. So while fantasy is likely to persist in the nostalgia of the series, how that nostalgic fantasy relates to the facts on the ground in the political present is what we hope to frame in the remainder of this introductory essay as the work of this cluster.

Stranger Things' inconsistent thematics of race, gender, and sexuality must be analyzed in relation to the often-ugly contemporary politics of nostalgia. For us, the obscure reference to X-Men 134 unfolds worlds of childhood reading built from a non-identification, then and now, with the world around us. But we are living in a moment in which that and other references in the show are often treated as the exclusive preserve of white heterosexual men and self-professed "actual nerds" who draw frequently misogynistic boundaries (e.g. the "fake geek girl" memes) around the very sorts of objects and texts in which Stranger Things invests.9 Indeed, contemporary texts that share a fan base with Stranger Things have examined this very figure. For example, take Black Mirror's trenchant Season Four episode, "USS Callister." The episode draws a through-line between an aggrieved and isolated "actual nerd's" nostalgic attachment to a nerd ur-text, the original Star Trek (1966-1969), and his technologically-enacted violent and misogynistic power fantasies. These fantasies resonate with the real-world figures of the incel and mass shooter, rageful beings who evoke and oppose the complicated kinds of tragic violence that Dark Phoenix and her arguably feminist kin embody. So what is Stranger Things' attitude toward these entwined issues of nerdiness, masculinity, and misogyny, and how does it reshape the paradigms of masculinity it inherits from the mass culture of the 1980s: the cool hetero jock or tough guy that turns out to be a good guy despite his privilege (Jake Ryan in Sixteen Candles) or lack thereof (John Bender in The Breakfast Club), and the geek, often accused of being gay (and invariably played by Anthony Michael Hall)? Is our gendered investment in Stranger Things akin or askance to what Black Mirror is critiquing in "USS Callister"? And how do the politics of gender here converge and diverge with the politics of nostalgia now?

Stranger Things at first seems to retreat from a critical perspective on white masculinity by reproducing its 1980s sources' standard dichotomy between good nerds and bad jock-bullies, not only through the four boy protagonists' bullying, but also through the contrasting teenage male figures of Jonathan Byers (Will's older brother) and Steve Harrington (Nancy's boyfriend in Season One), respectively. But the show complicates its initial binary oppositions (poor/rich, sensitive/callow, outsider/insider), and the viewer's inclination to identify (with) Jonathan as a better love object for Nancy, by showing Jonathan's potential to be just as condescending and sexist toward Nancy as Steve, locating these qualities in class resentment about his status as a social outcast. But it is really Season Two's introduction of Billy Hargrove that is relevant to the question we are asking about the gender politics of our nostalgic investments, however fractured, in Stranger Things. For Billy is, in the contemporary parlance, an exemplar of toxic masculinity, effectively rehabilitating both Steve and Jonathan within the logic of the show.

Billy is a troubling amalgam of the stoner-metalhead outsiders of 1980s movies like River's Edge and the bullying jock insiders of any teen comedy of the period. In Season Two, he replaces Steve as the "king" of the high school, his royal status attained through hyper-masculine displays of strength, confidence, and violence and the threat of violence. Much of this plays out through his toxic relationship to his tomboy stepsister, Max, whose budding attraction to Lucas he finds intolerable due to his racism. Billy's violent eruption into the world of Stranger Things has the effect of emphasizing what "good guys" Jonathan and Steve are. Jonathan embraces freaky boyhood in taking brotherly care of Will after the younger character's traumatic experiences in the Upside Down during Season One. Similarly, Steve abdicates his high school throne and offers care to the boys as they begin to enter adolescence more fully, becoming an ersatz brother to Dustin in particular and providing him with a heteronormative holding environment on his road to masculinity. The arrival of Billy thus allows us to believe in Jonathan and Steve as good guys even as both of them seem pulled into Season Two's seemingly inexorable drive toward boys refusing the feminine within, girls claiming conventional femininities, and everyone going to the school dance in properly boy-girl pairings.

But Billy's arrival also stresses the violence involved in what, in her essay for this cluster, Aviva Briefel characterizes as the "straight nostalgia" of Stranger Things. Toward the season's end, the show reveals Billy's behavior as stemming from abuse by his authoritarian father, who assaults him, berating him as a "faggot" for his appearance and his failure to watch over Max, who has left the house unattended. Billy's father thus emerges as the paragon of the show's array of bad fathers (traced in Jason's essay), the figure positioned as transmitter not only of Billy's violence but of the younger bullies who harass Will and assault Mike in acts that approach gay bashing. The character system of Stranger Things, then, reveals the show's nostalgia as filled with fractured boys — and complexly gendered girls, from the brief-lived Barb to the powerful Eleven to the tomboy Max. It doesn't ruthlessly critique nostalgic attachment to nerdy texts and their centering of white male heroes, as does "USS Callister." But it mobilizes its nostalgic attachments to the 1980s to expose the fractured forms of gender and sexuality available to boys and girls then and now, pointing to the spaces of non-identification that those fractures both created in the past and still create in the present.10

It has shown itself less able to mobilize resources to expose the fracturing forces of race and racism. Whereas "USS Callister" underlines the nerdy protagonist's microaggressions toward a black associate and unawareness of how his white privilege serves him, Stranger Things makes only circumscribed moves toward addressing the racial exclusions of its nerdy boyhood. One example is Season Two's argument about Ghostbusters between Mike and Lucas. This argument is part of a larger one about the whiteness of nostalgia on Stranger Things that David Bering-Porter explores in his essay. He analyzes the split between liberal politics and neoliberal economics when it comes to race and ethnicity on the show, showing how both the liberalism and neoliberalism of Stranger Things trivializes anti-state, anti-patriarchal, and anti-racist forms of solidarity in the nostalgic name of white community. Elizabeth Reich also detects tremors of a fracturing futurity at the end of Season Two of Stranger Things, calling for the show to pursue a radical Afrofuturism that might allow it to move closer to, however asymptotically, the world-changing agency that nostalgia will almost always contract to a fantasy of power you don't actually have.

We hope with this cluster to pursue the violent fractures that nostalgia today entails. Each of us — some weaving in more personal details, others less so — seeks to grasp nostalgia now. Confronting nostalgia anew is pressing because extant accounts remain unduly beholden to critics whose historical present is no longer our own. The cluster takes up the legacies of critics such as Fredric Jameson and Susan Stewart, who famously critique nostalgia in "Nostalgia for the Present" and "Historicism in The Shining," and On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. They argue that nostalgia creates problems for thinking about the present. Its preponderance in the late twentieth century reveals, for them, the domination of cultural production by consumerism, and the failure of available modes of expression to address how we experience the present, much less the past that nostalgia falsely aestheticizes. At its worst, nostalgia, in this tradition — from which we have learned so much — seeks to repair the fractures of history with fantasies of a past that never existed.

This might still be true. But, because they were leveled in the 1980s and 1990s, these critiques of nostalgia demand reconsideration. Especially since the 2016 election, nostalgia has emerged as a public affect mobilized right, left, and center. The right is leveraging racism, misogyny, and xenophobia to "Make America Great Again." In response, liberals resist by recalling the hard-won gains of the Civil Rights Movement, feminist politics, gay liberation, and the culture wars. But these recollections sometimes domesticate leftist struggles, not least because they smuggle in nostalgia for a far more recent past. T-shirts, mugs, and bumper stickers proclaim, "I Miss Obama" and "I'm Still With Her." The center, meanwhile, seeks what is no longer there, what is more a death wish than a future: a culture of bipartisanship that depended on a middle class that is gone for good, but that is an object of intense longing (which Joel addresses in his essay). Nostalgia as a category might unify the public now. But its divergent forms violently divide us. Decades after the critiques leveled against it, this divided unity, this violence, indicates a need to reevaluate the aesthetics and politics of nostalgia.

Happily partaking of much that Jameson and Stewart condemn about nostalgia, Stranger Things is set in the very decade when, under the regime of Ronald Reagan, our political moment began to take shape. Despite its ostensibly liberal choices, the desire for the past embedded in Stranger Things' often beautiful homage to the 1980s must be analyzed in terms of the often ugly politics of nostalgia in the present. The essays here address heteronormative memories of adolescence (Briefel); violence and middle class modernity (Burges); new and old media (Rust); generic convergence and autonomous childhood (Middleton); white nostalgia (Bering-Porter); and racial ecologies of death that might contain Afrofuturist impulses (Reich). Taken together, these essays seek out the tensions, blind spots, and subterranean desires in nostalgia today, showing how the '80s that Stranger Things reinvents cannot avoid the fractures of the 1980s that remain ours today.

Joel Burges and Jason Middleton teach at the University of Rochester in the Department of English, the Graduate Program in Visual & Cultural Studies, and the Film & Media Studies Program. Burges is the author of Out of Sync & Out of Work: History and the Obsolescence of Labor in Contemporary Culture (2018), the co-editor of Time: A Vocabulary of the Present (2016), and is at work on Literature after TV: The Double History of Watching and Writing. Middleton is the author of Documentary's Awkward Turn: Cringe Comedy and Media Spectatorship (2013), co-editor of Medium Cool: Music Videos from Soundies to Cellphones (2007), and is at work on The Intimate Work of Horror.

References

- See James Phillips, "Distance, Absence, and Nostalgia," eds. Don Ihde and Hugh J. Silverman, Descriptions (Albany: SUNY Press, 1985), 64-75.[⤒]

- Jason Middleton, "Comic Book Melancholia," Los Angeles Review of Books, August 25, 2016.[⤒]

- Tom Baker, "10 Most Tragic Deaths on the History of Marvel Comics," WhatCulture. July 15, 2014.[⤒]

- Alex Abad-Santos, "Stranger Things is a Love Letter to the X-Men's Jean Grey," Vox, August 5, 2016.[⤒]

- Judith Butler, "Melancholy Gender, Refused Identification," in The Psychic Life of Power (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), 140.[⤒]

- These sentences draw directly on passages from two texts that influence my thinking above: Lauren Berlant, The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 269; and Jared Sexton, Black Men, Black Feminism: Lucifer's Nocturne (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 92. I also benefited from conversations in person and by text with Rachel Haidu and Emily Sherwood — and, it goes without saying, my co-author, Jason Middleton, and our editor, Dan Sinykin — in writing the entirety of my section of the introductory essay.[⤒]

- Ashley Reed, "Girls Feel Stranger Things, Too," Avidly, August 19, 2016.[⤒]

- See the almost too ubiquitous to require citation: Frederic Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991), and The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981).[⤒]

- Heben Nigatu, "Why the 'Fake Geek Girl' Meme Needs to Die," Buzzfeed, January 4, 2013.[⤒]

- We think a long note is order here, though we hope this introductory essay has enacted and performed the following such that it is almost not necessary for readers. Throughout, we have used the term non-identification to suggest the social and psychic spaces that open up when normative modes of being feel like the negation of a subject position you are supposed to inhabit in the world, such that the world itself becomes an object you want to negate. As such, non-identification repeatedly fractures your capacity to participate easily in supposedly affirmative forms of world-making, even as you may seek to do so with difficulty again and again. These affirmative forms might remain desirable across your life, but a potently negative or “non” relation to them persists even as you pursue them. We think non-identification differs from related terms such as José Esteban Muñoz's well-known concept of "disidentification," which is akin to Stuart Hall's mode of "oppositional reading." Muñoz describes disidentification as a strategy of resistance and survival for minority spectators; not a utopian effort to break free of a dominant ideology altogether, but a "working on and against" that "that tries to transform a cultural logic from within" (Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 3). Non-identification is certainly related to — and could even happen simultaneously with — disidentification in that, as we trace here, the former involves volatile attachments that you are not supposed to have: for example, to texts that imagine other worlds for you, to bodies that don’t resemble your own, and/or to subject positions non-identical to yours. But those attachments do not necessarily have as their primary purpose the transformation of a cultural logic from within. They instead function as a means of working through what it means to be, sometimes violently, non-identified with normative modes of being and ways of world-making (such as being and relating as a boy). In this, we are probably closer to Leo Bersani in Homos in this essay, working with attachments that demand "a redefinition of sociality so radical that it may appear to require a provisional withdrawal from relationality itself" (Homos (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995), 7). As we have tried to explore in the final section of the introduction, the politics of such non-identification could lead in many directions given its at least provisional withdrawal from sociality. It could lead towards, on the one hand, feminist rage and leftist critique as much as, on the other, the social and cultural violence of the incel, the mass shooter, and actual nerds. [⤒]

Past clusters

Abortion Now, Abortion Forever

African American Satire in the Twenty-First Century

Ecologies of Neoliberal Publishing

Feel Your Fantasy: The Drag Race Cluster

For Speed and Creed: The Fast and Furious Franchise

Leaving Hollywoo: Essays After BoJack Horseman

Legacies — 9/11 and the War On Terror at Twenty

Minimalisms Now: Race, Affect, Aesthetics