Choosing a Good

The rise of American conservatism, as James Scott has argued, is reflected in mainstream Hollywood films of the past thirty years such as The Right Stuff (1983), the Rambo series (1982-2008), and The Terminator franchise (1984-2009). 1 As a corporate machine, the Hollywood studio system creates these tributes to American rugged individualism and the triumph of free-market ideology to yield vast profits. Simultaneously, however, these decades have produced a new form of popular independent film seemingly with the very different aim of offering diverse, global perspectives that seek to challenge American cultural insularity. Taiwanese-American director Ang Lee embodies this new independent film by blending diasporic cultural alignments, political resistance, and gender swerving with striking cinematography and American screenwriting. While directing box-office hits, Lee has made a career as an independent artist who can put an avant-garde flourish on traditional Hollywood fare, whether as director of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), Hulk (2003), or Brokeback Mountain (2005). But throughout this same period, Lee and his creative and business partner James Schamus have increasingly envisioned their films within the structures and demands of mainstream corporations. The neoliberal endorsement of individual free agents, global free enterprise, and evolved capitalism characterizing Rambo: First Blood also typifies—both thematically and, more unexpectedly, formally—Lee's and Schamus's films. Looking at Lee's cinematography and Schamus's screenwriting, we can see a studio use its "alternative" vision as a way to identify and uphold their valuable brand within the international contemporary economy, even bolstering this corporate identity with Schamus's performative management style.

Take the nine-minute Chosen (2001), Lee's short film for BMWFilms.com. 2 A sophisticated driver escorting a Tibetan child-monk from a city dock to suburbia skillfully avoids thugs driving far less elegant, resilient, or stable cars: a wobbly Jeep Grand Cherokee fishtails (recall that pesky rollover problem?), a Mercedes and Dodge Neon are smashed up, while the BMW zooms safely away. Upon delivering the boy to the authentic monks, the driver opens a tiny gift containing an Incredible Hulk bandage, cheekily making a product-placement for Lee's next film. 3 By purchasing an elegant, technically superior BMW—"The Ultimate Driving Machine"—a debonair commuting parent can experience a more exciting, cosmopolitan life while protecting their own "chosen" cargo in the backseat (which is also why, as a supplemental testimonial, Lee's son plays the buckled-up child-monk). We might note too that the title "Chosen" aligns various types of exceptionalism: as Lee puts it, "I like that title, 'Chosen,' whether it's the chosen little Buddha, or the chosen driver, or the chosen car." 4 What he likes is symbolically aligning the consumer choice to buy a BMW with a political decision to support Tibetan sovereignty through the driver's decision to save the "little Buddha." By linking the Tibetan struggle for independence, American luxury consumption, artistic filmmaking, and a powerful European brand, the film promotes globalization beyond BMW's mandate, implying that indirect, effective support of Tibetan autonomy can mutually benefit producer and consumer alike. 5

More unusual than its ideological claims is the film's sophisticated alignment of its formal devices with this familiar rhetoric of joint profitability. Lee instructed the musical editor to compose a hybrid piece combining traditional Tibetan music with classical baroque music, the latter deliberately evocative of the German aesthetic tradition and alluding to the elegance of BMW cars. We learn that certain East/West fusions can be exquisite, a veiled slight to the other kinds of East/West amalgams with which BMW contends for market share (Lexus, Acura, and other Asian brands modeling their less expensive products on European luxury cars). From a visual perspective, by turning the car chase into a finely choreographed quadrille that uses the full depth of the mise-en-scène—most other car chases look entirely two-dimensional in comparison—the film not only implies that BMWs can outmaneuver Jeeps and Mercedes, but that BMWs and their drivers are able to perceive their worldly situation from an altered, more wide-ranging perspective. Demonstrating this aesthetic and symbolic space, one striking scene first shows the cars chasing one another around shipping containers from the perspective of the baffled drivers: perplexed mice scurrying around the maze of late capitalist logistics (figure 1). In the next shot, however, Lee suddenly provides us with a different, aerial perspective, revealing the BMW and its driver effortlessly winding through the maze while the other cars blindly attempt to trail them (figure 2). A literally shifted perspective—from lateral to aerial—suddenly opens up an entirely new vision and understanding of the car chase, as we begin to understand that we can best maneuver through the thorny contemporary universe of global commodity purchases and political subversion in a BMW. More generally, through this quick change in visual perspective the scene opens up a newly perceived space that aligns precisely with the position Lee's films seek. Previously unrecognized connections between child Buddha, hired driver, and luxury product, and thus between world politics, corporate firms, and commodities, become newly discernable and desirable through this freshly seen space.

Chosen is a commercial, albeit a particularly sophisticated and well-crafted one, and we expect it to express corporate ideologies. But this film's narrative-political homologies and formal perspectival tropes—that is, shifts in perspective opening up different spaces—illustrate a widespread story extending beyond film-commercials to millennial indie films' collaboration with the business world. Instead of operating in opposition to Hollywood's financial demands, such films reveal a screenwriter's and a director's vision not only merging with the corporate bottom line but articulating and visualizing a newly imagined corporate subjectivity in which companies locate value and profit in perspectivalism and pluralism. Formal synergy between outlaw, corporate benefactor, multinational producer/screenwriter, and an arty, diasporic director, symbolized here through the cultivation of BMWs as progressive commodities, marks Lee's films, providing a fascinating case study of neoliberal independent—what I am calling neo-indie—filmmaking at the millennium. The neo-indie film instantiates a political economic model in which, to quote David Harvey, "the social good will be maximized by maximizing the reach and frequency of market transactions" and the global corporation is the inevitable institution for such expansion. 6 In the best of these films, the aesthetic shifts, cinematography, screenwriting, and score reflect a precise identification with the corporation and its definition of social good—that is, with additional market transactions, additional consumers/spectators, additional profits, and so on. By the late 1990s, multipronged expansion required the pursuit of more consumers—and found those consumers through collaborations that crossed the East/West divide, as in Chosen. 7

More specifically, Lee's diasporic Taiwanese aesthetic fluidly aligns with the corporate mandates of James Schamus's American-based production companies, the not-so-silent partner in the two men's working relationship. In 1991, Schamus, a New York-based film scholar and screenwriter, co-founded Good Machine Productions. Tiny Good Machine became Focus Features in 2002 when it was acquired by French media monolith Vivendi SA, merged with minimajor USA Films, and placed under the umbrella of Universal. When Vivendi subsequently sold most of its stake in Universal to GE in 2004, Schamus remained in charge, eventually becoming CEO of an even larger Focus Features. Finally, in 2011, GE sold its NBC Universal unit (NBCU) to cable giant Comcast. 8 Over nearly two decades, Lee's eleven films, varying in genre, have been produced with Schamus and these increasingly globally-financed corporations. As Lee puts it, "James is always part of the movie, I don't see him as a producer or writer. He's a collaborator." 9

By first analyzing these films' intercultural narratives, frequently adapted or written by Schamus, and then, in the following section, examining the recurring vantage shifts of Lee's cinematography, we shall see how formal perspectivalism supports Good Machine's and Focus Features' corporate identity as a profitable company promoting global pluralism. Neo-indie films such as The Wedding Banquet (1993) and Taking Woodstock (2009)—two films on which Lee and Schamus worked especially closely—trope hybrid cultural and sexual identities (and more allegorically, diaspora) to imply that alternative perspectives exist best within a corporate business structure. The narrative and shots are symptomatic of a similar perspective-shifting impulse we saw expressed in Chosen, as difference is ordered into a smooth, easily palatable, and crowd-pleasing view. When Schamus describes his production company's corporate philosophy by saying, "We want to get people who are turned away from the mainstream to turn a bit toward it, and those turned toward it to turn a little away," he is precisely describing the formal signature of the exemplary Lee/Schamus film. 10 But, in another sense, by using his management position to portray a self-conscious scholar-analyst of his business, Schamus also performs the distinctive alterity his film brand promises. Thus, in the last section of the essay, we will see how Taking Woodstock, a dramatization of an unlikely producer-in-training, operates as the ultimate commercial for Good Machine/Focus films: even its CEO has a "different" perspective on what it means to manage the business. Advocating for the mutually beneficial relationship between alternative filmmaking, cultural tolerance, and global capitalism, Good Machine/Focus films envision goodness from the perspective of a corporate person maximizing its social good through increased sales: the hypothetical "good" machine of capitalism. More particularly, their films present an excellent example of independent film's transformation throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s: what began as a material distinction—independence from Hollywood's labor and capital circuits—had become merely a difference in perspective.

Film studies may have largely abandoned auteurism, yet in Lee's case, the field seems to have made an exception. Despite Lee's intimate, longstanding relationship with Schamus and his increasingly multinational production companies, critics still analyze their films as the autonomous creations of a visionary immigrant auteur and not as the corporate commodity of Good Machine or Focus Features. In the process, we have not been able to see the corporate-aesthetic perspectivalism described above. Discussions surrounding Brokeback Mountain often accept these films as "Ang Lee's," as when Erika Spohrer provides a powerful reading of the film as an auteur director's subversion of the Western genre. 11 Yet to make sense of these films—indeed, to make sense of any film at our current moment—requires analyzing a more complex aesthetic, cultural, and financial collaboration than much film analysis, auteurist or otherwise, is willing to tackle. It is precisely this formal corporate aesthetics we must examine. While the corporate nature of contemporary filmmaking would come as a surprise to no one, the formal characteristics of the corporation's artistic view—the auteurism of the contemporary corporation, we might say—is regularly sidelined. 12

Recently, some critics have nudged beyond auteurism by considering Lee/Schamus films in their material relation to culture by exploring their global status. 13 Yet by focusing almost entirely on the films' culturally diasporic aspects, the assumption has been that Lee is reflecting his own autobiographical relationship with a lost homeland. From a different perspective entirely, film critics not focusing on Lee's work open up a fruitful critical space by analyzing independent film's complicated authorship and means of production, overlapping with the new "critical corporate studies." 14 Denise Mann's Hollywood Independents: The Postwar Talent Takeover (2008) considers the independent movement of the 1950s, while Chris Holmlund and Justin Wyatt's Contemporary American Independent Film: From the Margins to the Mainstream (2005) examines the negotiated relationship between independent filmmakers and studios in the 1970s and thereafter to chart independent films' re-absorption into the corporate system (Good Machine followed this narrative arc when it was bought by Vivendi and then GE). 15 Extending this logic of collaboration, Jerome Christensen argues that studios self-consciously expanded and exploited corporate personhood for market purposes, creating cinematic texts that reveal their corporate viewpoint and identity. 16 When powerful directors such as Stephen Spielberg, George Lucas, and Spike Lee are at work, Christensen suggests, they can take personal responsibility for their films precisely because they already have corporate responsibility for them as presidents of a brand. 17 That is, they are in the rarified position of possessing both individual and corporate personhood, a condition implying that, now, only corporations can obtain the status of full human beings. 18 Good Machine and its subsequent incarnation, Focus Features, both enjoy and explore this new status through their films.

While refining and promoting the commodity known as "Ang Lee films," these companies operate as powerful corporate persons attempting to define their vision and responsibility, whether social or "individual" (that is, whether to society generally or to shareholders specifically), at a time of unprecedented commercial power. It is the intentions of these corporate persons that demand our focused attention. Moreover, Schamus/Lee films articulate a socioeconomic compromise embodied as perspectival pivoting. Like Chosen's advertisement for Hulk boxed within a commercial for BMW, their films package commercials within commercials to profit from "Ang Lee films." Schamus has admitted as much, describing "one of the only real sales tools independents have at hand" as "the 'politique des auteurs.'" 19 Yet even Schamus's keen reflections on his culpable role in the corporate process bespeak a total dedication to his product: perspectivalism, through and through. Their films instantiate this commitment, revealing that an artistic vision such as Lee's and a scholarly production run by Schamus can be completely compatible with a corporate subjectivity such as Good Machine's or Focus Features'. Both realizing and frustrating the notion of thought-provoking "good flicks," these movies also fulfill that other descriptor in the company's original name: "machine." That is, neo-indie films define goodness as imagined by the corporate subject, one who resembles a mechanized, collaborative hulk made by Ang Lee and Industrial Light & Magic. Schamus and Lee give this hulk a voice and an aesthetic.

Scripting Independence: From Production to Perspective

"The death of American independent film has been prophesied more than once over the last few years, but finally we have a date on which to pin our grief," declared Anthony Kaufman in the Village Voice. 20 It was May 2, 2002, the day Universal Studios acquired Good Machine, incorporating the independent company into the conventional studio system. Ted Hope, one of the original company's cofounders, chose to distance himself from Focus, the new, amalgamated company: "I came to the realization that I had no desire to build an empire... I felt hampered by the responsibilities of feeding the machine and running a corporate enterprise" (Kaufman). But Schamus, the other cofounder, responded differently: "This is exactly where we've been heading for 12 years... When a seed gets put in the ground, you water it" (Kaufman). The diverging metaphors, the machine and the garden, precisely capture the company's complicated identity. Hope's Good Machine is a voracious, mechanized empire whereas Schamus's Good Machine is a munificent organic entity. The ravenous corporate machine demands sales, profit, and expansion regardless of individuals' wishes, whereas the benevolent organization spreads social good (when defined as non-Hollywood product) through corporate growth. These descriptions dramatize the contradictory logic of the good corporation, reiterating a historical tension in classical liberalism between egalitarianism on the one side and libertarianism of the free market on the other. 21

The paradox of the good corporation marked independent films such as Lee's from the very start. Following the 1948 mandated divestitures, the decline of the studios and the rise of television and talent agencies challenged independent producers. A film such as Marty (1955) could be made independently for a pittance but required a larger studio (United Artists) to release, advertise, and distribute it to make millions. 22 In the 1990s, Good Machine followed this model of production, distribution, and profit. Without a distribution arm of its own, the company relied on larger ones to create its first real breakout hit: The Wedding Banquet. As Schamus explained, with that movie they "were able to do what you only dream of in independent film... which is to have a bidding war." 23 The Samuel Goldwyn Company bought and distributed Banquet from Good Machine, grossing $28 million on a film costing less than one million dollars to make. Throughout the 1990s Good Machine's identity became synonymous with this calculated strategy. Taking on unpopular subjects, they produced films that proved enormously profitable when accompanied by a savvy, high-concept sales-pitch. Schamus brilliantly marketed Happiness (1998) using this approach: Todd Solondz's dark film depicting pedophilia was spun as a critique about the overproduction of desire. 24 The more acceptable standpoint of critical social commentary defused a disturbing point of view—the pedophile's. While the metaphor of the baseball minor leagues has been used to describe Good Machine's approach, a 1990s dot-com/high-tech start-up (like Google) better captures the model here. 25 A small, edgy start-up aimed to create a profitable, alluring concept that would be invested in by venture capitalists or bought by much larger corporations, generating a windfall and the promise of continuing profits. 26

Simultaneously, independent film evolved from an independence of production to an independence of perspective, what Filmmaker magazine describes as "an alternative point of view"—reimagining the pedophile's pathology as social commentary on late capitalism. Between the 1940s and the 1980s, "independent" referred to a film produced without the studio system's financing and distribution power, but when mega-corporations created "studio independents" in the 1990s and 2000s (i.e., "mini-studios" such as Fox Searchlight, Focus Features, Warner Independent Pictures, and Paramount Vantage), they assisted their smaller in-house units with production, financing, promotion, and distribution. 27 Acknowledging this reality in Contemporary American Independent Film, Holmlund points out that "independence" now means something closer to style: "the label suggests social engagement and/or aesthetic experimentation—a distinctive visual look, an unusual narrative pattern, a self-reflexive style." 28 Although Holmlund does not spell-out the transformation, once "indie" no longer means independent from corporate production, "independence" simply provides another marketing opportunity. These alternative viewpoints, ostensibly independent from the mainstream view, find perfect expression in corporate names such as "Searchlight," "Focus," and "Vantage," each suggesting the act of looking elsewhere. A global corporation can invest in perspectivally "independent" films to hedge or diversify, similar to a portfolio management strategy of buying varying-sized companies. While a "large-cap" action film needs to make huge profits to break even, one "small-cap" mini-studio film that becomes a hit (i.e., Juno, Little Miss Sunshine, etc.) compensates for dozens of duds. Finally, with the neo-indie viewpoint film, the act of capturing perspective trumps all other concerns. When critics wonder, as they did, if Brokeback Mountain is queer enough, they pose the only aesthetic evaluation a neo-indie film can natively prompt: does it have a sufficiently alternative point of view?

Early Lee/Schamus films consistently aimed for the latter definition of independence: not independence from production but independence as perspective. Whether examining Schamus's screenplays or Lee's camera angles, we can see how each consistently reveals the corporate containment of subversive perspectives through formal features. Although mostly financed independently, albeit by grants from the Taiwanese government, their early films seek to present a moderately unconventional perspective on various cultural issues to underscore, paradoxically, the value of individual perspective. Employing techniques of intercultural fusion, they make an alternative point of view (for example, ethnically Chinese or gay) palatable to a wider audience. And by taking that perspective and merging it with older, more conventional, "uplifting" genres, they increase the size of their audience even more. Guided by Schamus's screenwriting, the misunderstandings of romantic comedy, family drama, and comedy of manners blend with nostalgic melodramas of immigrant assimilation, intergenerational conflict, and interethnic love affairs. When such narrative strategies are combined, these films display an amalgamated perspectivalism that could be sold to a broad, global audience as not quite Hollywood and not quite avant-garde independent. This compounded perspective collapses cultural difference into aesthetic difference, which can then be easily marketed as a desirable, slightly exotic film commodity.

Schamus's narratives, in other words, enable their films to connect unfamiliar views to more familiar perspectives in ways marketable to a mainstream audience, giving outside perspectives an insider track. We can see this containment strategy operating on a narrative level in The Wedding Banquet, the second film of Ang Lee's "Father Knows Best" trilogy, along with Pushing Hands (1992), and Eat Drink Man Woman (1994), films that Schamus also co-wrote and produced. As Schamus describes, he took Lee's tragic Banquet story about Wai Tung Gao, a young Taiwanese man living in New York whose parents cannot accept his homosexuality, and rewrote it as a classic 1930s screwball comedy of remarriage based on Stanley Cavell's film study, Pursuits of Happiness. 29 In the film, Wai Tung is a gay "yuppie capitalist" landlord whose parents fail to acknowledge his immigrant triumph because he is unmarried. Attempting to placate them, he agrees to a quick green-card wedding with Wei Wei, his young Chinese tenant, while also living with Simon, his lover. Much of the screwball humor of the film relies on the everyday deceptions this duality requires. Before Wai Tung's parents arrive from Taiwan the house must be scrubbed of the evidence of his life with Simon. Raunchy gay photos and sexually playful postcards are replaced with staged, humorless portraits. Eventually the Gaos discover that the "landlord" Simon is his true partner (the film's significant tweaking of the remarriage aspect) but not before the raucous, heterosexist wedding banquet of the title leads to sex between Wai Tung and Wei Wei. She becomes pregnant and Wai Tung and Simon nearly split up. By the film's end, these conflicts are more or less resolved. The Gaos do not have a traditionally married son, but because Mr. Gao feigns ignorance about his son's homosexuality—Schamus's crucial plot innovation—the parents end up with a deeper desire fulfilled: a grandchild. 30 Immigrant tragedy becomes a sympathetic, comedic portrayal of the American capitalist dream: namely, yuppie gay landlord with an heir-apparent.

Critics who point to Eastern/Western amalgamations throughout Lee's films nonetheless omit Schamus's transformative role in the narrative process. 31 Invoking Fredric Jameson's account of the "tourist-friendly" Third World film marketed to first world consumers, Sheng-mei Ma suggests that the "Father Knows Best" trilogy reveals "an increasing propensity toward exotic travel" designed to appeal to the bourgeois taste of First World tourists. 32 Building on Ma's notion of the intended viewer as a bourgeois consumer, my different point is that the ethnic fusions of the trilogy situate Good Machine in the corporate vanguard by creating a new paradigm for independent film—the alternative point of view as such. That is, the films frame not just the person but the perspective of a gay and/or Chinese immigrant as a valuable commodity that can be manipulated and sold to a mainstream audience. This sales pitch is not directed at consumers but at the studio itself, a way to recommit to its identity as a small indie production house.

One might object that not all Schamus/Lee collaborations reveal such obvious perspectival interchangeability as do Banquet and (as we shall see) Taking Woodstock, small budget films on which the two men worked together closely. Yet other Schamus screenplays imply, perhaps more elliptically, not only that these films must occupy a space of contained subversion, but that such a position is the key to Good Machine's purported social goodness. Take another instance of collapsing perspectives for both the social good of pluralism and the corporate good of profit. While writing Eat Drink Man Woman, Schamus renamed the Chinese characters with Jewish names and personalities before having them retranslated back into Mandarin. This strategy enabled him to write from an ethnic perspective more familiar both to himself and to his intended audience: "Ja-Chin, Ja-Ning, I changed them all to Sarah, and Rachel... I changed it globally and made everybody Jewish... I gave [Ang] the script, and he sat there in my kitchen, and read it and he goes, 'Wow, this is so Chinese!'" 33 Chinese becomes legible, acceptable, and profitable once translated into Jewishness. Schamus admits as much when he explains that the film industry "must have people who act and look a little differently from the norm, or differently enough so that they can sell difference, while at the same time we have to act in ways that are absolutely similar, and always the same." 34 While, on the one hand, Schamus's intercultural, trans-generic screenplays participate in the very selling of difference he identifies, on the other hand, his point is that even "independent" film creators, like himself and Lee, have no choice but to create, and to attempt to challenge convention, from within this constricted space.

Let's bracket for a moment one complication: namely, that Schamus himself provides the keenest insight on his role in a production and marketing process that turns a Ja-Chin into a Sarah. I'll return to this issue at the end of this section. For now, note that the motif of peering into foreign, often diasporic communities, whether Taiwanese or Jewish, is used in these films to allegorize alternative perspectives that might be unfamiliar to audiences. In other words, these films merge more familiar articulations of perspectival difference (a Jewish-American perspective) with less familiar ones (a gay, Taiwanese perspective) to turn ethnicity into a profitable commodity. In Banquet, the proverbial immigrant story of intergenerational conflict is fused with a less familiar gay, yuppie, and Chinese diaspora story. Later films continue the strategy of perspectival hybrids with a pro-integrationist Confederate (Ride with the Devil [1999]), a radical feminist swordfighter (Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon), a hyper-masculine gay cowboy (Brokeback Mountain), an S&M-practicing ingénue/double agent (Lust, Caution [2007]), and a business-friendly hippie (Taking Woodstock). In the process, Lee/Schamus films amalgamate alternative perspectives with generic cinematic identities (soldier, swordfighter, cowboy, double agent, hippie) to "sell difference" as independent perspective. And insofar as all these films primarily aim to sell different perspectives (here recombined with generic types) as independent ones, they also are fundamentally alike.

Banquet manifests this strategy structurally and thematically by depicting gay sexuality on a more traditional minority model of diasporic life, implying that Wai Tung's Taiwanese father is trapped in the same position as his son relative to traditional Chinese culture. 35 Living in the diaspora, being gay, and being Taiwanese are aligned narratively as a condition of contemporary culture. Like Wai Tung, Mr. Gao feels obligated to maintain a masquerade of traditional Chinese culture, nationalism, and patriarchal authority, a masquerade he sporadically undermines by attempting to abdicate such responsibility. For instance, he explains to his son that he joined the army not out of solidarity with the Nationalists but to escape an arranged marriage: "I got angry and just took off. We fought the Japs and the Communists and then I went to Taiwan. One day a relative escaped and brought a letter from grandpa that said that the Gao family was gone and it was up to me to continue the family name. I can't tell you how I feel about being at your wedding!" Wai Tung only hears the last part of the speech: the joy and pride his father now feels knowing that the family name will continue if a child is born. But Mr. Gao clearly tries to "come out" to his son by undermining the image Wai Tung has of him as the noble, brave patriarch. What Wai Tung assumed was a biography of heroism and nationalist valor—his father joined the army to fight for Chinese autonomy—morphs into a different story: his father, afraid to challenge patriarchal authority directly, runs away to live in the diaspora (Taiwan, in his case) and marry whom he wants. The scene establishes that Mr. Gao (as a young man) and Wai Tung occupy the same position vis-à-vis their respective fathers, as Wai Tung's gay sexuality becomes merely another way of living diasporically. 36

A similar alignment between and even conflation of two distinct perspectives operates in Ride with the Devil (1999). The central tension is the uneasy friendship between two people related by temperament, political beliefs, and social standing but separated by racial difference: in this case, a minority political opinion (Southern abolitionism) is depicted on the model of the gay closet. The freed slave Daniel Holt (who fights alongside his former master) becomes close to Jake Roedel, a son of a German immigrant abolitionist who must conceal his friendship with Holt to appease his Southern Confederate comrades. Employing a dynamic long-familiar to readers of Mark Twain, the film models their forbidden friendship on the homoerotics of the closet: there are many scenes of pillow-talk between the two men, including a scene played for laughs of Jake preferring to sleep with Holt on his wedding night. In one sense, these various examples reveal a sensitivity to "other" subjectivities, particularly apparent when the films subversively enlist popular, straight actors (Tobey Maguire, Jake Gyllenhaal, Heath Ledger) to temporarily queer themselves.

But in another sense, what we're seeing here is something other than tolerance. These films depict diasporic and gay perspectives as fungible cultural differences that can model all forms of difference for the broadest audience imaginable. Although the insistence and instantiation of this point varies from film to film (most obvious in Banquet than in any other), it remains crucial to each of them. Sometimes diaspora and other times gayness are portrayed as the most agreeable, fundamental form of difference: while Wai Tung's gay identity is often allegorized in the language of diaspora, Jake's abolitionist beliefs are portrayed in terms of the essentialist/social constructivist debate about homosexuality. Which is to say that sometimes Jake's beliefs are depicted as a racial birthright (he was born an abolitionist/gay) and sometimes they are a cultural inheritance (his family and culture made him an abolitionist/gay), but never are these beliefs depicted as chosen (he never decided to be an abolitionist/gay). These beliefs, which aren't in any real sense beliefs (he can't choose not to have them) but a set of practices intrinsic to his identity, are in conflict with his commitment to the slave-holding Southern culture. Jake, like Wai Tung and, for that matter, like Ennis in Brokeback, reveals himself in tension with his lived culture at certain closeted moments. But whether sexuality, race and ethnicity, or politics is the particular viewpoint under examination, in these narratives of perspectival collapse, cultural variation is always revealed to the audience, if not to the characters themselves, as an essential, lucrative interchangeability. Every Ja-Ning can become a Rachel, every gay yuppie is also a member of the Taiwanese diaspora, every Southern abolitionist is like a gay man in a heterosexist culture. Every difference in perspective is structurally identical, and through that structural sameness, every difference is potentially profitable.

This revelation, however, is at least as much Schamus's as it is mine. My footnotes to his interviews, articles, and comments imply as much. His persistently smart and candid observations on his role at Good Machine and Focus reveal a scholar-producer comprehensively scrutinizing the industry, an instance of what J.D. Connor has aptly described as independent films' "industrial reflexivity." 37 We might think, as I have at times, and somewhat uncharitably, of Schamus's self-reflections as a kind of ritualistic absolution from the various sins of contagion generated by his proximity to the corporate machine. Thus when he claims, as he did last year in the New York Times, "I'm not particularly a fan of late capitalism in general, but I realize our movies have to make a profit," he liberates himself to operate as one of late capitalism's particularly well-compensated fans. 38 But I have come to think that we might more profitably—so to speak—think of these self-reflections as a commitment to perspectivalism so pervasive that it is enacted at all levels of the corporate and managerial structure. Schamus must speak about his producer's role whenever possible not to distract us from the work he does but to do that work more proficiently. That is, what looks like a compulsion to speak the ugly truth of the business stands revealed as something else: an even deeper, more extensive commitment to perspectivalism as the brand identity of Good Machine and then Focus Features. Here the perspective Schamus must project on the world's screens is his own as producer. The production companies he runs require self-irony and canniness from their CEO to more integrally instantiate their trademark of perspectival canniness. Schamus's frank perspective is yet another turn of the screw, a way to reinvest in a company that profits from unlikely perspectives.

The Budget Aesthetic: Framing Perspectivalism

We have seen how Schamus's narratives put into practice the basic philosophy of the corporate entity, whether Good Machine or Focus Features, where outsider perspectives are given a space to respond to mainstream culture instead of being kept at a marginal distance from it (as the Focus Feature motto puts it, "speaking face-forward to the rest of the culture"). 39 And we have also begun to see Schamus's commitment to perspectivalism in film reflected in his public identity of producer-scholar, one who spins a unique perspective on the business he runs. In the final section of the essay, we will see how Schamus's performance of this brand identity at Focus Features culminates in Taking Woodstock. Yet first we need to understand more clearly how Lee's visual aesthetic contributed to fashioning this trademark for Good Machine and Focus Features.

Before Good Machine became Focus, the company's ostensible motto was "the budget equals the aesthetic." 40 This earlier motto and identity required the company to create perspectives without spending their budget on expensive explosions, CGI, big-name stars, or outdoor scenes involving helicopters and extras. But, in fact, the earlier aesthetic of Good Machine and the later mandate of Focus Features are entirely compatible with one another through an economical, signature technique regularly appearing early and often in Lee/Schamus's films: slow, unexpected shifts enabling the careful construction of scenes around pivoting camera angles. This camera pivot is not just a stylistic device but resembles the company's notion of changing or dual perspectives when one speaks "from outside the mainstream," that is, turned away, while "facing forward" to address it. If we saw in the previous section how Lee/Schamus films produce a collapsed, interchangeable, "independent" perspective within the film narrative, here we see these films trope or frame alternative perspectives visually to make other, alien views more familiar, approachable, and marketable to an increasingly varied audience. In other words, Lee's and his cinematographer's visual decisions masterfully echo the perspectival alignments between a diasporic perspective and a gay perspective that Schamus creates at the narrative level. Combined, these alignments sustain Good Machine's and eventually Focus Feature's corporate subjectivity and identity. They are the signature gestures of the Lee/Schamus machine.

One of these framed perspectives appears early in Banquet, when Wei Wei and Wai Tung temporarily produce the masquerade of a traditional, heterosexual Taiwanese couple while Simon takes up the role of landlord and "best man." Mrs. Gao has given her own wedding dress to Wei Wei, predicting it would fit: "It's a spiritual bond that passes from generation to generation. You were brought together by fate. You and our son" (figure 3). Of course, no such fate was involved. The two people are aligned through migratory human capital flows in a temporary financial and legal arrangement that only deceives his parents (he is her landlord and she fears deportation). But the careful triangulation of gazes on and between an object of speculation—between Simon, Wei Wei, and Wai Tung on the one hand, and between Ma and Pa Gao and Wei Wei on the other—neatly captures the association between diasporic living and closeted living. Although the triangles are slightly different (in one, Simon is the object of speculation, in the other, Wei Wei is), Wei Wei's dual role in both triangles underscores the essential sameness between diaspora and closet the film insists on. Similarly, Schamus has alluded to the presence of a "Jewish closet" in Spielberg's films, while Lee admits this conflation more explicitly: "I can really identify with being gay... because I identify with being the outsider." 41 The behavioral modification the closet requires is not limited to Wai Tung (or gay men): Wei Wei, as a Chinese woman living in America, must also play the role of a feminine, domestic housewife for her Taiwanese in-laws at the same time that Simon closets his embrace of precisely this role. Finally, the viewer is implicated in this triangle from Simon's perspective as the American and as the gay man, both because we are looking past him (and thus from his vantage point) but also because the subtitles translating the scene for uncomprehending viewers requires us, repeatedly, to stare at his behind.

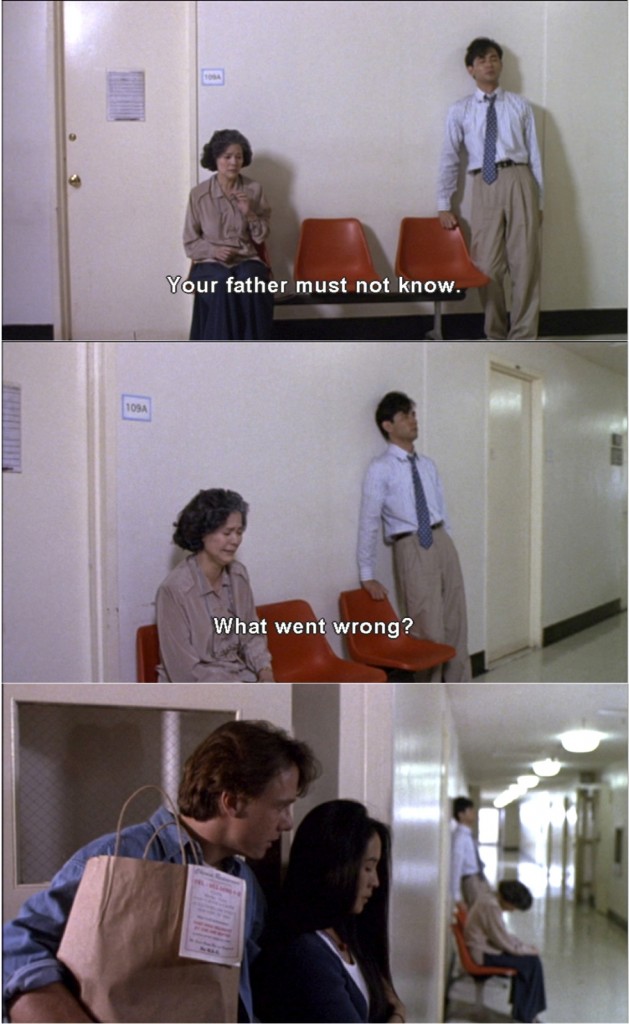

After the wedding banquet, Wei Wei reveals her pregnancy, leading to a scene dramatizing the closet as a flat, stagnant, claustrophobic space triangulating viewers situated on different axes. Mr. Gao has a stroke and Wai Tung reluctantly comes out to his mother at the hospital, admitting both his frustration and his marital deception. Dejected, she orders his silence: "Your father must not know... It would kill him. What went wrong?" Starting with a medium shot, the camera slowly tracks clockwise and retreats until we spot Simon and Wei Wei in the foreground of the frame, surreptitiously listening to the entire conversation around the corner (figure 4). Clearly, the closet is "what went wrong" in the family relationship, a point nicely dramatized when the narrow hospital hallway allegorizes the deceptive withholding and spying the closet generates from everyone. Mother and son are stuck in a stark and shallow space, unable even to face one another, while we are once again positioned with Simon, whose perspective is presented as different (i.e., gay) but less different than others (i.e., gay and Taiwanese) in the film. Like him, we try to make sense of the conversation as the foreign third party, learning about the other perspectives the film allegorizes.

Lee often pivots the camera in precisely this way—what I am describing as an aesthetic of self-conscious perspectivalism—to dramatize and expose for the viewer the workings and psychodynamics of closeted behavior that might be otherwise mysterious. The formal tracking shots and pivots that are so successful in Banquet are repeated with only slight differences in a succession of films. He inverts the same move in the final scene of Brokeback Mountain when Ennis opens up his tiny trailer closet to expose his shirt and Jack's both hanging on the closet door next to a postcard of the eponymous mountain (figure 5). In this instance, the camera begins from the exposed side, precisely where the hospital scene from Banquet ended. Both Ennis and the shirts appear in profile before the camera rotates 90°, over Ennis's shoulder, revealing the increasingly constricting space of his literal closet. Underscoring the point, Ennis "straightens" up the postcard of Brokeback (figure 6) perhaps to respect Jack's memory (tidying up a memorial) but also to repress the memory's sexual content. He puts Brokeback and the sexuality expressed there in a straightjacket. Symbolic of his loss, the shirts are flattened and stored: all remnants of intimate sexuality are closeted in Ennis's constricting life. The last shot of the film lingers here a moment before Ennis resolutely shuts the closet door and keeps them hidden inside. Thus, in both Banquet and Brokeback, Lee portrays the closet as a static, visually constricting space that the privileged viewer experiences and then occasionally escapes via a 90° spin. 42

Later films make similar cinematic moves. The adaptation of Jane Austen's Sense and Sensibility (1995), Lee's first film after the trilogy, revisits the same aesthetic of closeted, framed perspectives from a feminist angle to reveal women trapped in a closet of gazes, tracking and pivoting the camera to an almost identical purpose. 43 Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Lee and Schamus's collaboration immediately before the corporate purchase of Good Machine, combines all of these strategies to dramatize a fantasy of feminine freedom in the repressive culture of historical China. 44 But most importantly, Crouching Tiger frames perspectives as such (what I'm terming perspectivalism) to anticipate the philosophy of Focus Features, the corporation Good Machine soon becomes. As described on the NBCU website, Focus is dedicated to "films that challenge mainstream moviegoers to embrace and enjoy voices and visions from around the world." This narrative arc—from challenge, to embrace, to enjoy—precisely describes films enticing us through a kind of romantic looking that begins antagonistically but ends intimately, as do so many of the loves scenes in later Lee/Schamus movies (e.g., the brutal but passionate sex scenes in Brokeback and Lust, Caution).

Crouching Tiger dramatizes this allegory between film and its audience in the romance between Jen, the aristocratic and rebellious swordfighter, and Lo, her outlaw lover. In a twenty-minute flashback sequence, Jen recalls meeting Lo in the Gobi dessert and the Taklimakan Plateau. Similar to Jack and Ennis's violent roughhousing on the mountain, the two chase and fight each other (the "challenge" to "mainstream moviegoers") in a protracted episode of martial arts, finally ending in sex ("embrace and enjoy"). The scene begins from Jen's vantage point inside the confined space of her family's carriage, where she and we watch Lo in his pose of "Dark Cloud"—the frightening, long-haired, barbarian on horseback who attacks her father's guards (figure 7). The carriage's window frame conspicuously resembles both a movie screen and the sprocket holes that are sometimes partially visible on screen when the projector is misaligned. The film literalizes Jen's situation: she faces her alienation from her own experience as a misalignment between her family's expectations and her personal desires. She gazes at her desired life "on screen," protected in her audience-position, as if she were entranced by an exciting action film (and not, exactly, by the typical Good Machine movie). But when Lo looks back at her, catches her eye and, with a wink, reaches into her carriage to snatch her comb, her aesthetic distance immediately vanishes (figure 8). Her movie has not only slipped its sprocket holes but come to life, inviting her more direct interaction with it.

While her mother responds by fainting, Jen is made of sturdier stuff—Good Machine's ideal viewer. With yet another 90° camera pivot clockwise, she explodes out of her role as passive audience member, leaps from her carriage-as-screening box, and begins an odyssey for her comb and her sexual freedom (figure 9). Simultaneously, this scene reiterates the entire ideology of the perspectivally driven neo-indie under Good Machine, which is to challenge the mainstream audience to embrace and to enjoy its unexpected visions. At first we are shocked and worried for Jen in the face of barbarians, just as both Jen and her mother are appalled by their carriage-box screening of Lo. But the film pulls us and Jen in with Lo's wink, stealing into our private space represented by Jen's comb. Eventually, we too see the barbarian from a more sympathetic perspective: Lo bravely and honorably devotes himself to Jen, assisting in her sexual and psychological liberation. He is a feminist in barbarian clothing. And by watching him we, like Jen, enjoy an imagined taste of the nomadic, barbaric lifestyle.

The recurring gesture of the pivoting camera to trope perspectivalism allows us to make sense of a signature thematic operating throughout Lee's filmography: the performative identification with cultural difference. But the larger point I am making is that the decision to frame or view individual perspectives through more expected ones (Wai Tung's through Simon's; Jen's through the typical film viewer's) is not just a central identifying feature of these films but a feature identical to the larger aims of Good Machine productions, and later, of Focus Features. Just as Schamus and Lee sell the viewer a way to identify with a severely repressed perspective that might be exotic or even incomprehensible, Good Machine and Focus Features sell independent perspectives as an unfamiliar commodity that can be repackaged, reformulated, and familiarized through the "Ang Lee" imprimatur: the pivoting camera opening up a whole new outlook on the world. Through narrative and cinematography, characters like Simon or Jen model a more familiar view on an alternative world. At moments even Brokeback follows this pattern, since Ennis's frustrated yearning often mirrors Wai Tung's dual closeting in both the Taiwanese diaspora and the land of heterosexuality. 45 That is, to illuminate the perspective of a hyper-masculine, gay cowboy for uncomprehending audiences, Ennis is portrayed, like Wai Tung in Banquet, as a kind of gay immigrant in a foreign land, nostalgically pinning pictures of the remote gay homeland mountain to his closet door. Lee and Schamus attempt to make the closet experience sympathetic and knowable by modeling it on the seemingly more familiar diasporic immigrant experience. In every case, an exotic angle of vision is mapped onto whatever is deemed the more conventional and thus accessible one, enabling the production company to tell and sell the same story—"challeng[ing] the mainstream moviegoers to embrace and enjoy voices and visions from around the world"—over and over again.

Becoming Focus Features

After Crouching Tiger and the creation of Focus Features, Lee and Schamus's collaborations increasingly became multinational, corporate products: Hulk was produced by Good Machine, Marvel, and Universal, while Brokeback Mountain, Lust, Caution, and Taking Woodstock were produced by NBCU's Focus Features division, each with Schamus at the helm. More could be written about each of these films' use of perspectivalism as a commodity within an even larger corporate framework. Hulk, for example, often uses expensive CGI to produce an almost identical effect as Jen exploding out of her carriage in Crouching Tiger (figure 10), while the film's formal trope of mimicking comic book paneling arguably bespeaks an attempt to accommodate or figure the financial partnership with Marvel, the comic book company. Meanwhile, Taking Woodstock presents a neo-indie vision by underscoring the social and the financial benefits of modifying an unusual angle on the world for mainstream audiences.

But more pointedly, this film is where Schamus's self-consciousness about his implications in the international cultural economy pays off. Not only is it a particularly good example of the director's and producer's collaboration within a larger corporate structure; more crucially, Taking Woodstock removes the producer from the closet. The director's and producer's introductions to the published shooting script reveal this dynamic in action, beginning with Lee's brief Buddhist meditation abnegating film meaning: "Unlike all my other movies, I myself didn't suffer during the making of it, so I really have nothing of interest or meaning to say about it... the film might be somewhat interesting, even though there's nothing meaningful to be found in it." 46 He thus defers to Schamus's descriptive, philosophical interpretation of the film as the continuation of the Woodstock movement. Quoting Bakhtinian literary critic Saul Morson, Schamus explains that the film celebrates the "plurality of temporalities" of the Woodstock story by "excavat[ing] alternative histories" (xii). And the particular alternative history the film reveals is the coming out story of the neo-indie producer.

Adapted by Schamus from Elliot Tiber's memoir, the film explores Tiber's entrepreneurial role in organizing, promoting, and profiting from the 1969 Woodstock concert. In Schamus's version, Elliot begins to distance himself from his repressive Jewish family while acknowledging his homosexuality, thus revisiting themes from Banquet and Brokeback. We also learn that the legendary concert was really the occasion for thousands of people to experience individually a 1960s Happening. When Elliot denigrates his own "trivial" family issues, suggesting that when placed in the proper perspective his problems are irrelevant to the culturally significant event at hand, another concert organizer corrects him, explaining that a hypothetical universal or objective view is meaningless: "Perspective is what shuts out the universe. Everyone with their little perspective. It keeps the love out." Her view comes to represent the film's unexpected yet implicit point. Individuals' perspectives (or "alternative histories," to use Schamus's phrase) are only esteemed after some other entity—most obviously, the corporation—frames them. Or to put it slightly differently, an individual's "little perspective" is merely conditionally valuable, only "love[d]" by others once it is generalized and represented cinematically as perspectivalism.

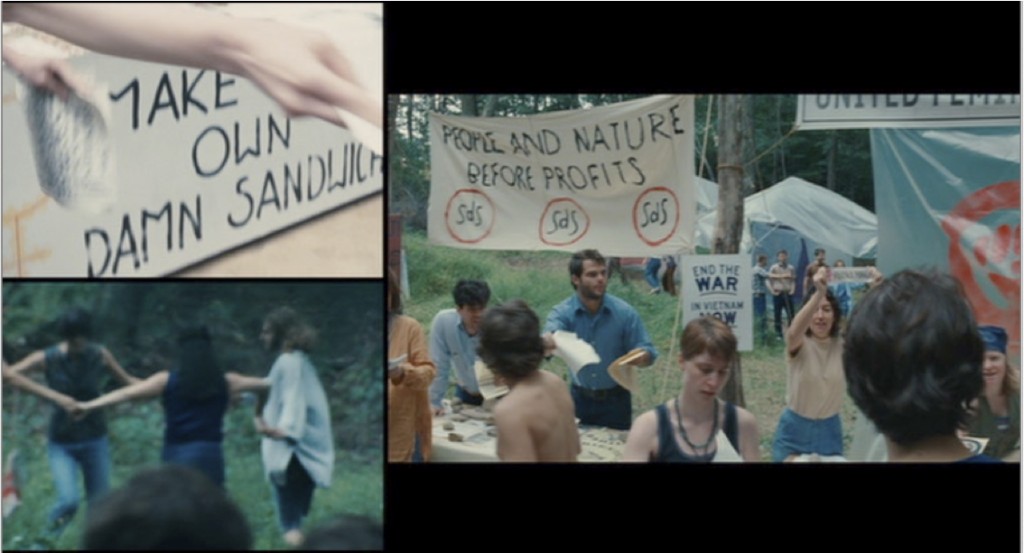

The film visually dramatizes this point by balancing multiframed perspectives against one another, indicating that the many different events and viewpoints occurring simultaneously during Woodstock can be represented harmoniously. 47 Frequent split-screens pay homage to Michael Wadleigh's documentary, Woodstock (1971), but the strategy used to capture these vignettes reveals Taking Woodstock as the product of a very different era. Lee gave young filmmakers (working as extras) 16mm cameras; throughout the shooting of Taking Woodstock they filmed his restaging of the event from their own viewpoint. Their footage was then spliced together as a montage accompanying, or juxtaposing, Lee's 35mm master-shot. In figure 11, the 16mm footage is on the left while Lee's 35mm master-shot, with Elliot's head in the foreground, is on the right. On the one hand, this strategy implies that a history of Woodstock is always incomplete and can only be recalled from many different people's perspectives—including, as this shot reveals, those of socialist groups such as Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), whose banner reads "PEOPLE AND NATURE BEFORE PROFITS." But, on the other hand, by taking actual individuals' footage of the making of Lee's film and incorporating it into the totalizing Lee/Schamus/Focus Features' account of Woodstock, the film effectively contains and domesticates other perspectives such as SDS's anti-capitalism. Focus Features can make a film that includes alternative perspectives precisely because they are retained as secondary alternatives to Lee's master-shot, in the same way that the two grainy 16mm views by amateur filmmakers are juxtaposed with, and subordinate to, a single, high-definition, polished 35mm shot. As the corporate vision is aligned with Lee's own, each individual perspective, even an anti-corporate one, is incorporated into the organizing montage. 48

Indeed, the film is fascinated by the idea of capitalist-supported protests. Supported by "heavy lawyers" and paper bags of cash, corporate "suits" are portrayed as an integral part of the hippie event, traipsing across Max Yasgur's fields with young, visionary organizers like Michael Lane. At times the film seems less to dramatize Woodstock and more to present Elliot as a Focus Features CEO-in-training, producing a transformative theatrical piece in the Catskills. After all, with Lane's support Elliot does the work of a studio producer: applying for permits, scouting locations, giving press conferences, arranging vendors, hiring security guards, and distributing tickets. When the locals harass him, Elliot recognizes that he must avoid peace and love to focus on potential profits: "This whole thing is about commerce, right?" He reiterates the point at a press conference, albeit in confused stoner-lingo:

You are asking about freedom. The very essence of the enterprise, of all enterprise, especially free enterprise. And freedom could be considered, and is often considered, you know, to be just another word for being free. Therefore, there will be no train to freedom. Train has already left the station.

His mostly inane speech is interpreted to mean that the concert will cost nothing to attend ("we are going to free all the songs"), frustrating his co-organizers' aims for big profits. But the quick, libertarian jump from freedom to free enterprise, masked as drug-induced word association, neatly aligns with the philosophy of Focus Features as a distinct brand within NBCU. That philosophy argues that while complete freedom is a fallacy ("there will be no train to freedom"), one can attain moments of freedom within free enterprise. Elliot's free-music message, resembling Radiohead's popular pay-as-you-want strategy with their release of "In Rainbows" (2007), is snuck into a corporate microphone, one actually bearing a retro NBC logo (figure 12). 49

No longer could Schamus repress his own desires: he had to be explicit. He would become Elliot/Demetri Martin. As Elliot implies in this scene—one Schamus reports that he took great pains to write carefully—ambiguous, subversive, and invariably "independent" perspectives like Elliot's (or like the young filmmakers' whose 16mm takes are incorporated into Lee's montage) best exist within a corporate frame. At the film's end Lane describes his dream for a Rolling Stones concert that will truly cost nothing for the listeners to attend, what became the disastrously violent Altamont Free Concert later that year. Here the film is explicitly arguing that the absence of capitalism is unreasonable and dangerous and that despite its problems the free market produces the social good of keeping anarchical rage in check. According to this argument, if a company had been hired for security (instead of the loose agreement organizers made with the Hell's Angels) the deaths at the latter concert might have been avoided. Although Lane's peaceful, "totally free" concert flopped, he accurately foresees the post-Woodstock moment of the 1980s and beyond: "Everybody's gotta chase the money now, right? We're all probably gonna sue each other, but that's cool." Like Lane, Taking Woodstock is cool with the idea that legal disputes over profit-ownership are as much a part of Woodstock's legacy of freedom ("free enterprise") as Elliot's experiences of personal, political, and sexual liberation ("the train to freedom").

Schamus's self-conscious revelations make the producer central to the story, even if Taking Woodstock might be simultaneously mocking its own collapsed distinctions between different kinds of freedom. But such irony can be easily reincorporated into the brand, since it nicely serves the purpose of defining their machine—now, Focus Features—as the "good," hip one. Indeed, this is increasingly not just Schamus/Lee's but NBCU's own conception of its corporate identity: the hip company that can profit from self-ribbing, which the NBC network show 30 Rock so often provides through Alec Baldwin's comical portrayal of an arrogantly charming NBCU/GE/"Kabletown" executive, ambitiously marketing the next great microwave or reality television show. 50 More broadly, the conflation between different forms of freedom is the real story of neo-indie filmmaking over the last thirty years. The synergy between Lee, Schamus, Good Machine in the 1990s, and Focus Features in the 2000s serves as an excellent, even allegorical case study precisely because Schamus consistently operates both as screenwriter and producer. Like George Lucas and Spike Lee, he writes films (for a dependable, loyal director) as a studio CEO, one attempting, like Elliot, to balance freedom with free enterprise. Whether with low-budget films such as The Wedding Banquet or blockbusters such as Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Lee/Schamus films frame and domesticate individual perspectives with narrative strategies such as Banquet's alignment of diaspora and the closet, or with artistic camera tracking and pivoting in Sense and Sensibility and Crouching Tiger (among others). In turn, these strategies operate with a corporate identity that explicitly markets itself as an independent vantage, speaking from one position to address another. The consistent goal is to nudge the "mainstream" marketplace towards pluralism and toleration, thus increasing the company's market share for the pluralistic, tolerant films it sells. One can speak into an NBC microphone and advocate for the gift economy as long as NBCU forecasts eventual profits from that speech. The Focus logo at the beginning of Taking Woodstock swirls subversively and psychedelically while NBCU, like Elliot, sells tickets to the show.

My analysis here challenges traditional accounts of these films to suggest that still-popular conceptions of neo-indie film are erroneous. Looking more carefully at collaborations like Lee/Schamus's reveals how "the brilliant director" marketing strategy masks a different corporate ideology: namely, the idea that independent perspectives work best from within a corporate framework. Focusing our analysis on the true corporate authors of "independent films" illuminates the cultural products of companies like Good Machine and Focus and, in the future, of Fox Searchlight, Miramax, and others. Perhaps these other corporate films depict formal and stylistic signatures we hardly think of seeking out. We too often neglect the complicated financial and aesthetic collaboration of indie filmmaking, just as film critics leave out Schamus in the Lee/Schamus partnership. While it might be particularly surprising that queer critics, presumably the most receptive to repressed partnerships and homosocial relations, have tended to ignore the ramifications of this longstanding collaboration between two "partners for life," this blindness seems less about queer critics missing a queer feature of these commodities and more representative of a blindness or aversion to corporate aesthetics, and the nature of the commodity in general, common in contemporary cultural analysis. 51

Such contextualization and re-focusing could lead to very different readings of these films than the ones presented here. After making Hulk, Lee defensively claimed that the experience of big-budget studio filmmaking was liberating:

People are saying that independents are supposed to... When you have no money, you're noble, you're independent. When you make a big movie, you're a sell-out. It didn't happen to me. To me, that's the ultimate freedom. Even money is not an issue. You just do whatever you want! (Laughs) Ultimate indulgence. 52

Lee has boarded Elliot's Freedom Train, where free enterprise liberates absolutely. Yet despite his "ultimate freedom," fears about selling out linger here. Focus Features films are also writing and masking anxiety about collaboration with the enemy, whether that enemy is a foreign country, the military, or corporate "suits" (as in Taking Woodstock). And while their very different recent film, Lust, Caution, has a distinctive historical milieu and context of reception in China, collusion with the enemy is the film's obvious concern: Chinese collaborationists with Japan during WWII are targeted by a group of rebel nationalists. Collaboration becomes a violent and erotically-charged temptation, such that Wang Chia-Chih, the double agent leading her mark to his death, can't resist saving his life and turning collaborationist herself. A similar subtext also operates in Hulk in its subplot about striving scientists collaborating with defense contractors. "How'd you like to come work for Atheon, get paid ten times as much as you now earn, and own a piece of the patents?" asks Talbot, one ambitious corporate-scientist working for a Raytheon look-alike, trying to recruit Bruce Banner and Betty to his own particular dark side in the military industrial complex. Talbot's threats escalate after they rebuff him: "There's a hair's breadth between friendly offer and hostile takeover," he warns, foreseeing the tremendous business opportunities in selling a hulk-like super-soldier. Only Bruce Banner as the huge, enraged Hulk manages to suppress Talbot's ambitious plans. But this exceptionalism itself suggests how much power is now required to resist the corporate obligation for increased profits, whether that corporation is "Atheon," Raytheon, NBCU, or, in its latest hulk-like form, Comcast-NBCU.

Lastly, perhaps these films are registering a new phenomenon of our age: the fear of corporate identity loss that comes with both a "friendly offer and hostile takeover." In this case, Focus Features, in its marriage to NBCU, worries about the lost autonomy it possessed as Good Machine. It is no longer a production company supposedly driven by aesthetic concerns instead of the bottom line. Certainly Schamus's abandoned partner Ted Hope thought as much. Focus is now just another capitalist machine. Of course, we have seen the fallacy of this conception of the company, since Good Machine's mandate of promoting pluralism for corporate profit was always compatible with, if not identical to, the aims of Focus Features and NBCU. More pointedly, these films expose the mistake of locating in diaspora or hybrid cultural identities, whether gay, hippie, cowboy, Taiwanese, feminist, or some combination, a critique of globalization. 53 The neo-indie film proves how easily cultural diasporas, portable wealth, and varied audiences triumph over grounded capital and a single, national audience in the global marketplace. Pluralism, diaspora, globalization, and artistic direction are entirely compatible and even mutually beneficial, as the Lee/Schamus partnership proves. And while there are, arguably, better corporations and worse corporations, distinguishing between the good machine and the bad machine is entirely irrelevant to these films and their aims. When we imagine that alternative perspectives turn some corporate machines into good corporate machines, we turn away from the aesthetic and profitable work these films do so well.

Lisa Siraganian is Assistant Professor of English at Southern Methodist University, and is currently a Visiting Scholar at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. She works in twentieth-century literature and culture, and her book, Modernism's Other Work: The Art Object's Political Life, is forthcoming from Oxford University Press. She adds in acknowledgment:

I would like to thank J.D. Connor, Darryl Dickson-Carr, Dennis Foster, Jason Gladstone, Shari Goldberg, Brian Hewitt, Eva Rueschmann, Nina Schwartz, several anonymous reviewers, and the editors of Post45 for their helpful comments and suggestions on this essay.

References

- #1 James Scott, "The Right Stuff at the Wrong Time: The Space of Nostalgia in the Conservative Ascendancy," Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies 40, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 45. See also Michael Ryan and Douglas Kellner, Camera Politica: The Politics and Ideology of Contemporary Hollywood Film (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1988).[⤒]

- #2 Chosen is one of eight short films starring Clive Owen that make up The Hire, BMW's successful film series originally produced for the web and later released on a DVD. The films were directed by Lee, Guy Ritchie, John Frankenheimer, and Alejandro González Iñárritu, among others.[⤒]

- #3 The chase is expertly choreographed and resembles an "Ang Lee Film" as much as any other. Working on Chosen with longtime-collaborators on his films (Frederick Elmes, Tim Squyres, Mychael Danna), Lee used the exquisite fight sequences in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) as models for the car chase.[⤒]

- #4 Chosen, Director's Commentary, BMWfilms.com.[⤒]

- #5 Buying a BMW supposedly protects a young monk's freedom and Tibet's sovereignty particularly through viral, new media advertising of a global brand. Since the film is now distributed only via video-sharing sites like YouTube, new forms of viral networking enable savvy global corporations to partner with religious groups (Tibetan monks) and filmmakers for imagined political results. Tibet's and its monks' long struggle with China over sovereignty has been publicized in the West, with the "Free Tibet" publicity campaign begun in London in 1987, hunger strikes in 1998, and violent protests surrounding the 2008 Beijing Olympics. See Jane Ardley, The Tibetan Independence Movement: Political, Religious and Ghandian Perspective (London: Routledge, 2002) and Melvyn C. Goldstein, The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).[⤒]

- #6 David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 3.[⤒]

- #7 The intimate friendship between the boy and the driver contrasts with the embrace of an imposter monk in cowboy boots to warn us about potentially inauthentic Eastern/Western amalgamations, perhaps an allusion to cars like the Geo Prism, another hyped Eastern/Western collaboration.[⤒]

- #8 Anti-trust regulators at the FCC and Justice Department permitted Comcast's purchase of a majority stake in the company in January 2011; at its merger, the new company was valued at USD$30 billion. Yinka Adegoke, Dan Levine, Eric Beech, "Comcast completes NBC Universal merger." Reuters, 29 January 2011, online edition.[⤒]

- #9 Gillian Mohney, "Ang Lee and James Schamus: Partners for Life," Interview Magazine blog, 19 November 2009.[⤒]

- #10 Carlo Rotella, "The Professor of Micropopularity," New York Times, 26 November 2010, online edition.[⤒]

- #11 Erika Spohrer, "Not a Gay Cowboy Movie?" Journal of Popular Film & Television 37, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 29-30. While his status as auteur is sometimes challenged, as by queer film critics after Lee won an Academy Award for Best Director of Brokeback, generally the brilliant-auteur model holds firm, and he is depicted as a tolerant craftsman-auteur working in multiple genres; see, for example, Robin Wood, "On and around Brokeback Mountain," Film Quarterly 60, no. 3 (Spring 2007): 29-30. D.A. Miller's analysis of Brokeback, the most challenging to Lee-as-auteur, argues that gay viewers were asked to "mistake a middling piece of Hollywood product for a major work of art;" "On the Universality of Brokeback Mountain," Film Quarterly 60, no. 3 (Spring 2007): 50. Similarly, William Leung considers whether the "typical Ang Lee film" is queer (and decides it isn't); William Leung, "So Queer Yet So Straight: Ang Lee's The Wedding Banquet and Brokeback Mountain," Journal of Film & Video 60, no. 1 (Spring 2008): 23-42. For another interesting discussion of the film, see Joshua Clover and Christopher Nealon, "Don't Ask, Don't Tell Me," Film Quarterly 60, no. 3 (Spring 2007). For a broader discussion of auteurism as commercial approach, see Timothy Corrigan, A Cinema Without Walls: Movies and Culture After Vietnam (New Brunswick, 1991), 101-36, and "Auteurs and the New Hollywood" in The New American Cinema, ed. Jon Lewis (Durham, 1998), 38-63.[⤒]

- #12 Important exceptions to this trend that strongly inform my own claims here include J.D. Connor, "'We'll eat you up we love you so': Warners Gone Wild," Post45: Contemporaries (6.29.11), and Jerome Christensen, America's Corporate Art: The Studio Authorship of Hollywood Motion Pictures (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2011), forthcoming.[⤒]

- #13 Christina Klein, "Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon: A Diasporic Reading," Cinema Journal 43, no. 4 (Summer 2004): 18-42 and Shu-mei Shih, "Globalization and Minoritisation: Ang Lee and the Politics of Flexibility," New Formations: A Journal of Culture/ Theory/ Politics 40 (2000): 86-101.[⤒]

- #14 Purnima Bose and Laura E. Lyon, eds., Cultural Critique and the Global Corporation, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 3.[⤒]

- #15 Denise Mann, Hollywood Independents: The Postwar Talent Takeover (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008) and Chris Holmlund and Justin Wyatt, eds., Contemporary American Independent Film: From the Margins to the Mainstream (London: Routledge, 2005). See also Emmanuel Levy, Cinema of Outsiders: The Rise of American Independent Film (New York: New York University Press, 1999), Stephen Prince, A New Pot of Gold: Hollywood Under the Electronic Rainbow, 1980-1989 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2000), Deidre Pribram, Cinema and Culture: Independent Film in the United States, 1980-2001 (New York: Peter Lang, 2002), Geoff King, American Independent Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005), Greg Marcks, "The Rise of the 'Studio Independents,'" Film Quarterly 61, no. 4 (2008): 8-9; and Michael Newman, "Indie Culture: In Pursuit of the Authentic Autonomous Alternative," Cinema Journal 48, no. 3 (Spring 2009): 16-34. Interest in the corporate, collaborative authorship of typically "auteur" films increased after the publication of David Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985) and Thomas Schatz, The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era (New York: Pantheon, 1988).[⤒]

- #16 Jerome Christensen, "Studio Authorship, Warner Bros., and The Fountainhead," The Velvet Light Trap 57 (Spring 2006): 18, 20. He views a film such as Warner Brothers' The Fountainhead (1949) not by focusing on its powerful screenwriter (Ayn Rand), director (King Vidor), or star (Gary Cooper)—although each of these figures importantly relates to the corporate vision—but by analyzing Warner Brothers' response to postwar legislation such as the Trade-Mark Act of 1946.[⤒]

- #17 Jerome Christensen, "Spike Lee, Corporate Populist," Critical Inquiry 17, no. 3 (Spring 1991): 589.[⤒]

- #18 On the role of CEOs' narratives in conceptions of corporate personhood, see Eric Guthey, "New Economic Romanticism, Narratives of Corporate Personhood, and the Antimanagerial Impulse" in Constructing Corporate America: History, Politics, Culture, ed. Kenneth Lipartito and David B. Sicilia (Oxford, 2004), 321-42.[⤒]

- #19 Stuart Klawans, Annette Michelson, Richard Peña, James Schamus, Malcolm Turvey, "Round Table: Independence in the Cinema," October 91 (Winter 2000): 10.[⤒]

- #20 Anthony Kaufman, "Ghost of the Machine: Mourning Has Risen for Independent Film," Village Voice, 28 May 2002, online edition.[⤒]

- #21 For a brief overview of these debates in contemporary political philosophy, see Thomas Nagel, Secular Philosophy and the Religious Temperament (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 113-14.[⤒]

- #22 Mann, Hollywood Independents, 16. For an excellent discussion of UA's production and marketing strategy for Marty and other small films, see Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company that Changed the Film Industry, Volume 2, 1951-1978 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987), 79-82, 146-51.[⤒]

- #23 Ann Hornaday, "A Film Scholar Conjures Up a Hit Machine," New York Times, 20 February 1994, online edition.[⤒]

- #24 James Schamus, "The Pursuit of Happiness: Making an Art of Marketing an Explosive Film," The Nation April 5/12, 1999, 34-35.[⤒]

- #25 Hornaday, "Film Scholar."[⤒]

- #26 Nor can one assume that studios were conservative and independent companies were progressive; as Mann points out, the independent company's responsibility to earn a profit to prove and to maintain their independence led, instead, to the opposite scenario (Mann, Hollywood Independents, 22). Similarly, according to director Greg Marcks, today's independently-financed films "feel the pressure to 'self-develop'"—that is, to adjust the script to the mainstream marketplace just as producers and studio executives do for studio films (Marcks, "Studio Independents," 8).[⤒]

- #27 The precise definition of contemporary independent film is still debated. According to Pribram, "a film released in the United States is considered independent if it has received no studio financing, is distributed by a non-major, and has no prominent stars" although she points out notable exceptions to this definition (Pribram, Cinema and Culture, xvi). Geoff King argues that many "different (overlapping) modes of independent practice" exist (King, Independent Cinema, 10). For financial accounts of indies' development see Arthur De Vany, Hollywood Economics: How Extreme Uncertainty Shapes the Film Industry (London: Routledge, 2003), Edward Jay Epstein, The Big Picture: Money and Power in Hollywood (New York: Random House, 2005), and The Hollywood Economist: The Hidden Financial Reality Behind the Movies (Brooklyn: Melville House, 2010).[⤒]

- #28 Holmlund and Wyatt, Contemporary American Independent Film, 2. Holmlund also notes Filmmaker: The Magazine of Independent Film's definition: "Independent film has always been about alternative points of view, whether they be expressed in experimental approaches or through crowd-pleasing comedies" in "25 New Faces of Indie Film 2003," Filmmaker: The Magazine of Independent Film (Summer 2003), online edition.[⤒]

- #29 "A Pinewood Dialogue with Ang Lee and James Schamus," Interview Transcript (pdf), moderated by David Schwartz. November 9, 2007. Museum of the Moving Image, 6.[⤒]

- #30 Lee and Schamus, "Pinewood," 6-7.[⤒]

- #31 See William Leung's comparison of Lee's Sense and Sensibility and Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon, Chris Berry's discussion of the specifically Chinese cultural aspects to Brokeback, and Gina Marchetti's analysis of Hulk as an icon of the Chinese diaspora: William Leung, "Crouching Sensibility, Hidden Sense," Film Criticism 26, no. 1 (Fall 2001): 42-55; Chris Berry, "The Chinese Side of the Mountain," Film Quarterly 60, no. 3 (Spring 2007): 32-37; Gina Marchetti, "Hollywood and Taiwan: Connections, Countercurrents, and Ang Lee's Hulk," in Chinese Connections: Critical Perspectives on Film, Identity, and Diaspora, ed. Tan See-Kam, Peter X Feng, and Gina Marchetti (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009), 95-108.[⤒]

- #32 Sheng-mei Ma, "Ang Lee's Domestic Tragicomedy: Immigrant Nostalgia, Exotic/Ethnic Tour, Global Market," Journal of Popular Culture 30, no. 1 (Summer 1996): 192-95.[⤒]

- #33 Lee and Schamus, "Pinewood," 7.[⤒]

- #34 Klawans et. al. "Round Table," 9.[⤒]

- #35 For a related discussion of the commonalities between the closet and the diaspora in film, see Ruth Johnston, "The Jewish Closet in Europa, Europa," Camera Obscura 18, no. 52 (January 2003): 1-33 and Schamus's discussion of the "Jewish closet" in "Next Year in Munich: Zionism, Masculinity, and Diaspora in Spielberg's Epic," Representations 100 (Fall 2007): 53-66.[⤒]

- #36 While some film critics have recognized the centrality of Mr. Gao to the thematics of Banquet, he has been interpreted as a patriarch instead of as a man forced into a closet of cultural masquerade. Mark Chiang reads Mr. Gao as a failing patriarch trying to transfer power to his son while David Eng does not discuss the role of Mr. Gao. Mark Chiang, "Coming Out into the Global System: Postmodern Patriarchies and Transnational Sexualities in The Wedding Banquet," in Q & A: Queer in Asian America, ed. David L. Eng and Alice Y. Hom (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998), 374-96 and David Eng, "Out Here and Over There: Queerness and Diaspora in Asian American Studies," Social Text 52-53 (1997): 43-46. It should also be pointed out that both Mr. Gao and his son are committed, above all, to capitalism.[⤒]

- #37 J. D. Connor, "The Biggest Independent Pictures Ever Made: Industrial Reflexivity Today," in Blackwell's History of American Cinema, volume 4, 1976-present, ed. Roy Grundmann, Cindy Lucia, and Art Simon, forthcoming.[⤒]

- #38 Rotella, "Professor of Micropopularity."[⤒]

- #39 Matthew Belloni and Stephen Galloway, "Focus Movie Boss Brings Avant Garde to Hollywood." Reuters.com 21 January 2010.[⤒]

- #40 Hornaday, "Film Scholar."[⤒]