The Daily Planet

"Superman is, after all, an alien life form," the horror genre writer Clive Barker notes in his introduction to Neil Gaiman's The Doll's House (the second volume of Gaiman's remarkable serial graphic novel, The Sandman): "He's simply the acceptable face of invading realities." He may have noted too that the acceptable face that an invading alien life form takes—in a type of world that consists both of itself and an unremitting commentary on itself—is that of a mild-mannered reporter on The Daily Planet. 1

I have, in a series of pieces, been setting out the pedagogical principles of this type of society: a self-inciting and self-reporting form of life that I redescribe as "the official world." 2

The throughput of this larger account is the work of Patricia Highsmith, whose novels and stories are fixated on the invading realities of species life on the daily planet—albeit the life of a species apparently intent on putting an end to itself, and doing so, as Highsmith puts it, "under the weight of officialism." The relentlessly brilliant, and relentlessly narrow-cast, stagings of an autotropic order of things makes for the "strange air of captivity," the "precarious life," and the "flavour of the unearthly"—I take all three phrases from Strangers on a Train (the first novel Highsmith published under her own name)—that define the official world, and draw chalk-white boundary lines along its edges.

The primary zones of distinction on the daily planet are these: the space of the game, the scene of the crime, and the form of the work of art. These reenactment zones are, it turns out, scale models of the official world, but at the same time working models in it (not just analogies to it, but also analogues of it). They are, as it were, scale models of the modern social system, which is then, in effect, a life-size model of itself. For this reason, if Highsmith's work is the strange attractor of these pages, my primary attention is to delineate the constituents of an official world that crisscross her work, and so to cast that world in relief, or to recast it in the presence of alternative, or warring, or ending worlds.

This piece then turns in part on Highsmith's novels Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley and the microworlds they model. These microworlds include the office (the architectural office, for example, in which worlds are drafted and modeled into existence); the theme park ("The Kingdom of Fun," a collection of demarcated repeating zones—the merry-go-round, the tunnel of love, and so on—small worlds after all); the train car, a rotating and repeating place without a place; the game space (which Hitchcock literalizes, in the real-time tennis game, in his film version of Strangers); the scene of the crime and the returns to it; and, not least, the artwork.

Games, forensics, and the work of art everywhere indicate each other in Highsmith's fiction (and not just there): they are prototypes of a unified and autistic world. These violent and reflexive zones are fractally self-similar (the emergence of comparable conditions in diverse systems is a defining attribute of modernity). And each, in turn, looks like, as Highsmith puts it, "a horrible little work of art." 3

To phrase it a bit differently, these are zones in which "each line, each figure, every angle—the ink itself vibrates with an almost intolerable violence." 4 These extremely formal zones of rehearsal and reenactment epitomize the epoch of social systems. They epitomize the internality, autonomy, self-referentiality, and staged character of, say, the Cold War game worlds of Herman Kahn, or the overlit interaction spaces of institutional ritual of Erving Goffman, or the insulated bureaucratic zealotry exhibited in The Pentagon Papers. They epitomize too—and this is the crux of the matter—the condition of the work of art in the systems epoch.

The aesthetic is the contemporary demarcation zone par excellence. And if aesthetics is "the science of the a prioris of perception," 5 it provides something like a perceptual blueprint of this world—if one takes into account how the official world blueprints itself as it goes and so, improbably and against all odds, goes on.

One art form that enters directly into Highsmith's suspense writing is the wildly popular genre (selling more than 50 million issues a month) that she worked on for the first decade or so of her career as a novelist: comic books—the illuminated books of the second machine age. 6 The brutal simplifications of that art form (Highsmith worked primarily on superhero comics) encode the senses of precarity, captivity, and unearthliness in her work. The comic-book genre provides the iterative model of an unremitting and systemic violence—a Cold War violence suspended in its premonition and induced in its preemption. It provides living diagrams of the ongoing catastrophes of modernization—and with those diagrams the intimation of counterfactual or alternate worlds, a war of the worlds, and the end of the world.

It provides models of ego and alter—and so of alter-ego—that shape Highsmith's talented killers from Strangers on a Train on. There is something of a likeness between the sort of superheroes, often with laboratory-induced superpowers, whose adventures Highsmith plotted at the drafting table and typewriter—Whizzer, the Human Torch, the Destroyer, Captain Midnight, Black Terror, Ghost, the Champion, Golden Arrow—and the posthuman psychopaths that populate her novels. The comic-book genre provides the laboratory conditions of what I will be describing as Highsmith's experimental novels, their species life, and the control conditions—the humanities lab—proper to an autogenic and self-conditioned world. Or, as the psycho-killer Bruno puts it in Strangers, "Guy and I are supermen." 7

In these pages, I want first to set out in a bit more detail what I mean by the official world and to trace its contours via several recent experimental models of it, fictional and real. I will then turn to a few scenes in Highsmith, scenes that remain remarkably consistent across their different scenographies, living spaces that make life interfere with life. Life and death in those spaces take place (to adapt W. G. Sebald's formulation) "between history and natural history"—or, more exactly, take place at that turning point of collective catastrophe at which "history threatens to revert to natural history." 8 (It is of course the "between" of this duality that must be interpreted, here via a series of instances, in the sections that follow. 9) Examining those spaces will make it possible to locate, in very preliminary fashion, what this form of life and its institutionalizations have come to look like in contemporary accounts of it. One might speak here of the distinction between the modern age and a modern world—in that the first discovers the conditions that the second applies to itself. (More on this, in a moment, by way of the epoch-making reenactment zone, the experiment—the staging area, or dress rehearsal, of a reflexive modernity.)

The Official World

The argument of the book from which this piece is drawn can be stated simply: a modern world comes to itself by staging its own conditions. A modern world is a self-conditioning and self-reporting one. If, prior to the nineteenth century, society could not describe itself, now it cannot stop describing itself—in an attempt to catch up with what it is generating. 10 Or, as the great science fiction writer Stanislaw Lem neatly put it: "In the Eolithic age there were no seminars on whether to invent the Paleolithic." 11 A modern society—which is to say, a continuously self-monitoring, auto-updating, and modernizing one—is what Durkheim (inaugurating modern sociology, and so indicating a society on the way to self-description) described as an "almost sui generis" society. The autotropic character of that world makes up what Durkheim also would call a social fact.

There are three general premises to this argument.

First, if a modern world comes to itself by staging its own conditions, it must consist both of itself and its self-description, denotation, or registration. A modern society, to the extent that it is modern, takes note of itself as it goes along. The mode of contemporary society—what I have called the official world—everywhere launches models of a self-modeling form of life. In doing so, it curates a world.

Second, if a modern world is a self-reporting one, a modern society must be bound to what Max Weber, early on, described as the self-documenting qualities and self-descriptive techniques that are the defining attributes of the second modernization. The modern world is an official world not merely in its administrative a priori, and not merely in the spreading of the administrative a priori across the social field, but in its bending of the will to know the real to the will to produce the real: the official world does not merely denote itself as it goes, but also takes note of the fact that it is a fact-producing act. 12 If it stops commenting on itself, it dies.

Third, the model for this self-staging world is then the modern work of art. We know that the modern work of art interrogates itself with an unremitting and unsparing intensity as to its own nature and singularity. It leads thinking in a circle, by leading art back to the expression of its own conditions. The work of art thus epitomizes an autonomous, self-reflexive, and so self-epitomizing world. At every point, it re-uses reference as self-reference. But reflexivity today is cheap. Hence to the extent that it does so, the work of art is then both exceptional and exemplary in what we can call the epoch of social systems. It is exceptional in its autonomous relation to, as they say, the "outside" world. It is exemplary in that it provides the very model of the autonomization of that world, its stand-alone, internalized, and demarcated character. In this way, the artwork makes the world appear in the world and unceasingly marks that it does so. 13

This is, in short, the paradoxical status of the sui generis artwork in the company of contemporary social systems or forms of life. The advent of the discipline of sociology indicates a society on the way to self-description—the achievement of the "almost" autonomous society, or what the microsociologist of contemporary intramural institutions Erving Goffman calls "our indoor social life." The modern social system and its demarcation zones—like the modern work of art—perform their own unity. 14

This also means, it will be seen, that the official world must continuously check and mark the distinction between what's in its zone and what's outside it. 15

The reflex question then, "What is 'outside' the official world?" is the question that it, from moment to moment to moment, puts to itself. It consists in the renewing, recording, filing, retrieving, reenacting of it. The official world knows, that is, that it has another side, an outside, and must reckon with this paradox at every moment—as in the extremely formal conditions of the game, we must see through it in order to play it and to single it out from the world. 16 This paradox is the nature, or second-hand nature, of an indoor social life, one turned away from what has recently been described as "le Grand Dehors" (or, the Great Outdoors.) 17

The New Experimental Novel

We might then have begun, in approaching Highsmith's Cold War—or perpetually post-war—world, with Brecht's dictum that "human beings learn no more from catastrophe than a laboratory rabbit learns about biology." 18 And what, after all, is the new novel, from Zola on, but a machine for conducting experiments? 19 One in which the species conducting the experiment and the one submitting to it are one and the same? The unreal reality of the perpetual post-war world—from World War II to World War Z—oscillates between history and natural history. These are the coordinates of what Highsmith calls an "Imaginary Zoo" and its "glass cells." 20

They are the presuppositions of the experimental conditions of precarious, captive, and alien life in her work. The point not to be missed is that the appeal to either side of this distinction—history, natural history—ends up on the other and so leads into tautology: hence "the perspective of human history and that of natural history are one and the same, so that destruction—and the tentative forms of new life that it generates—work like experiments, experiments in which the life of the species is concerned." 21 For the moment, let me outline these experiments in which species life is concerned via two recent reports on the prospects, if that's the right word, for tentative forms of new life on the daily planet. 22

Consider, first, this example of a postwar form of life, one at the lower range of life and form, and so perhaps a good way to take a baseline pulse of these general conditions. Here is the opening of Max Brooks's recent bestseller, World War Z, an unexpectedly compelling novel subtitled, "An Oral History of the Zombie War":

Greater Chongquing, the United Federation of China

[At its prewar height, this regime boasted a population of over thirty-five million people. Now there are barely fifty-thousand. Reconstruction funds have been slow to arrive in this part of the country, the government choosing to concentrate on the more densely populated coast. There is no central power grid, no running water besides the Yangstze River. But the streets are clear of rubble and the local "security council" has prevented any postwar outbreaks. The chairman of that council is Kwant Jing-shu, a medical doctor who, despite his advanced age and wartime injuries, still manages to make house calls to all his patients.]

The first outbreak I saw was in a remote village that officially had no name. The residents called it "New Dachang," but this was more out of nostalgia than anything else. Their former home, "Old Dachang," had stood since the period of the Three Kingdoms, with farms and houses and even trees said to be centuries old. When the Three Gorges Dam was completed, and reservoir waters began to rise, much of Dachang had been disassembled, brick by brick, then rebuilt on higher ground. This New Dachang, however, was not a town anymore, but a "national historic museum." It must have been a heartbreaking irony for those poor peasants, to see their town saved but then only being able to visit it as a tourist. Maybe that is why some of them chose to name their newly constructed hamlet "New Dachang" to preserve some connection to their heritage, even if it was only in name...Officially, it didn't exist and therefore wasn't on any map. 23

World War Z is, like Stoker's Dracula a century before, a chronicle, or better yet a chronologically-ordered dossier, made up of documents, files, numbers; grids, maps, committees, officialism; the administratively located, named, and recorded—and the unnamed and unrecorded, and so officially inexistent. It has the neutrality of a series of collated reports, and so that of a foreign and unreal reality, one in which familiarity with cultural and social circumstances has been suspended, the very same familiarity on which the writing and reading of novels depends.

Hence World War Z suspends the distinction (as does much horror fiction) between the world as it looks to us and the world as it looks without us—as does, for example, Cormac McCarthy's recent novel, The Road—and there too, "We're the walking dead in a horror film." 24 The daily planet reporter in this case is a medical officer. The coupling of biology and its administration is, of course, the mode of the experimental novel. We recall that the novelist and the doctor stand in for each other in Zola's manifesto for the experimental novel. Consider, with that, the function of fictions, or thought experiments, in the natural sciences, in pupating truth.

Here history and natural history in effect change places with each other. The account in World War Z compares the newly constructed, or reconstructed, to the long span of natural life (trees centuries-old) to the yet even longer span of unnatural or social life (the Three Kingdoms, two millennia-old). The Three Kingdoms and the Three Gorges Dam are in effect "floated" in relation to each other, in an ongoing comparison of what Highsmith calls "tales of natural and unnatural catastrophes." 25 This is the case because collective catastrophe marks the point where nature and history refer back to each other as two sides of a tautology. The effect is to neutralize the distinction between them. This neutralization intimates that the biological reflexes setting off construction and destruction both seem to have "long been foreshadowed by the complex physiology of human beings, the development of their hypertrophied minds, and their technological methods of production." 26

The official world is of necessity always patrolling the dikes of made culture, and in doing so, managing the catastrophes their construction sets in motion. The unspecified "outbreak" lies then in the interval between natural and unnatural disaster, and the walking dead, like the displaced in a war zone, carry their restlessness around like a plague.

But it is another and apparently gratuitous observation that in fact centers these opening pages and does so not in diegetic but in extremely formal terms. I am referring to the reenactment project that preoccupies the opening: the brick-by-brick disassembly and reconstruction of a small world, one irremediably in the "as-they-say" code of represented discourse ("New Dachang"). This is not exactly a constructed, or even a reconstructed, place, but the staging of one—a life-size model of itself as a "national historic museum." The town that is not a town and place that is not a place centers this entry into the novel. Hence it is where the novel describes its own conditions—and so frames a space of reenactment in which its own fictional reality applies. In this way it depicts a world that appears in the world—a demarcated space and the official world as observation zone.

INS

"Zombiedom," the English novelist Tom McCarthy has recently observed, "is just re-enactment without content." 27 McCarthy's novel Remainder (to which I will return at the close) is a novel about reenactment. The sponsor of these reenactments is the novel's human-like narrator, a first-person narrator who is not exactly a person but, as the speaking voice puts it, a "robot or zombie," and one who is irremediably alien or "second-hand" with respect to the world. 28

Re-enactment without content. If a modern world comes to itself through the staging its own conditions, then the prototype for that process is no doubt in the nature of the experiment. For one thing, the experiment is the defining form of observation, and the observation of observation, in the modern age. For another, observation via continuous reenactment, and commentary on it, are the presuppositions of the official world. That means the staging and repetition of natural processes via technical means, and the continuous alternation of observation and report, such that observing and reporting, and their repetition, may themselves be observed: "The experiment," as Hannah Arendt (following Heidegger) presents it, "repeats the natural process as though man himself were about to make nature's objects, this not for practical reasons of technical applicability but exclusively for the 'theoretical' reason that certainty in knowledge could not be gained otherwise." In Kant's terms: "Give me matter and I will build a world from it, that is, give me matter and I will show you how a world developed from it." 29 The experiment repeats the natural process by technical means, not for practical but formal reasons: it makes a world and shows its creation.

This—reenactment without content—is also, as McCarthy makes clear enough, the logic of the official world at its purest. Reenactments and their extreme formality take place, quite literally, under the weight of officialism and are acutely conscious of those circumstances. (Hence it's impossible to decide whether such reenactments take things to the breaking point or to the point of installation: we recall that, in Kafka, official decision-makers are as shamefaced as young girls.)

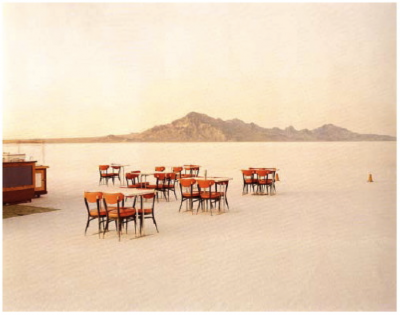

McCarthy serves as General Secretary of the International Necronautical Society he co-founded. (A meeting of the Society is pictured above, featuring—of course—re-enactors.) The Founding Manifesto of the Society (1999)—an "official document" authorized by the "First Committee, INS"—sets out its mission in these terms:

We, the First Committee of the International Necronautical Society, declare the following:

- That death is a type of space, which we intend to map, enter, colonize and, eventually, inhabit.

- That there is no beauty without death, its immanence. We shall sing death's beauty—that is, beauty.

- That we shall take it upon us, as our task to bring death out into the world. We will chart all its forms and media: in literature and art, where it is most apparent; also in science and culture, where it lurks submerged...

- Our ultimate aim shall be the construction of a craft that will convey us into death in such a way that we may, if not live, then at least persist. 30

These are the contours of what I've elsewhere called death and life in our wound culture—but in the terms of a "bureaucratic comedy, trimmed out in red tape." 31 The General Secretary's Report to the INS has as its ground zero, it may be noted, "Berlin: World Capital of Death." The report is replete with forensic detail, dossiers, archives, aerial surveys, sites of "marking and erasure, transit and transmission, cryptography and death." 32 It choreographs its own intent, with a hyperbolic and deadpan officialism: in its combination of a statement and a practice, it is sort of a practical joke—and the practical joke (it will be seen) is one of the dress rehearsal routines of the official world. The central place in McCarthy's account is, in fact, place that's not quite a place, but a transit and transmission zone, and the "primary reenactment space":

"I'd like to hire a room," I told him.

"What kind of room?" he asked.

"A space. An office."

"Right." 33

IRS

We may recall that Highsmith's most popular novel, The Talented Mr. Ripley, takes off from a practical joke involving the same reenactment zone, the office—albeit in this case, one that involves the reenactment of the office space itself.

The game that Tom is playing at the start of the novel "amounted to no more than a practical joke, really. Good clean sport." The practical joke, a sport or game, involves impersonating systems (that is, personating them)—in this case, not the INS but the IRS. The sport, more exactly, involves notifying strangers about back-taxes they need to pay; the checks are to be made out to "McAlpin" (Tom) and sent to a mail-drop address. Tom has "a list of prospects"; "a mauve-coloured stationery box"; a "stack of various forms" he has stolen; a typewriter; "typewriter paper stamped with the Department of Internal Revenue's Lexington address"; a "supply" of carbon paper, pens, paper, stamps, numbers; a telephone directory and a telephone, and so on. 34

The scene is thus like a diorama that might be called Office-dwelling Hominid in an Administrative State of Nature. And the whole point of the joke is that Tom knows he can't cash the checks he receives: his intention is predatory but only formally so. The pleasure is in entering into and staging, writing and voicing, an impersonal system as a practical joke, a play at home version of the IRS, and the scale model of an official world that operates just to keep operating—and getting client-victims to play along.

Here then is the description, in The Talented Mr. Ripley, of what Tom Ripley's harmless sport looks like:

He chose two forms headed NOTICE OF ERROR IN COMPUTATION, slipped a carbon between them, and began to copy rapidly the data below Reddington's name on his list. Income: $11,250 Exemptions: 1. Deductions $600. Credits: nil. Remittance: nil. Interest: (he hesitated a moment) $2.16. Balance due: $233.76. Then he took a piece of typewriter paper stamped with the Department of Internal Revenue's Lexington Avenue address from his supply in his carbon folder, crossed out the address with one slanting line of his pen, and typed below it:

Dear Sir:

Due to an overflow at our regular Lexington Avenue office, your reply should be sent to:

Adjustment Department

Attention of George McAlpin

187 E. 51 Street

New York 22, New York

Thank you.

Ralph F. Fischer

Gen. Dir. Adj. Dept.

The point not to be missed is how, in such passages, the white spaces on the page begin to signify —not exactly in the form of, say, Mallarmé's poetics, but like the blank spaces on official forms (which, of course, Highsmith types Tom typing). One cannot read this form, only copy it, and Tom's talent, of course, is to "copy rapidly"—and to copy uncontrollably. (Bartleby—a name Highsmith borrows for her main character in her novel A Suspension of Mercy (1965)—but Bartleby weaponized.) 35

The administrative system, like the form letters that enact and copy it, is a place-value system. The modern administrative a priori, as Weber made clear early on, replaces persons with positions. More exactly, the bureaucratic form of life means that persons are shifted, or rotated, through positions. They take their place, and so take place, in the same way that the zero allows digits to take value from a position and so to function as an autonomous system. The problem is keeping up the sequence and endlessly repeating it, by rotating persons through positions. 36 (More on this in a moment.)

Or, in case of the Ripley novels, Tom, the medium in person, takes their place. His talent is to see how place-value systems, their form and media, work—and how blindness to those systems works too. Uncontrollably reenacting, without content or character, Tom in effect turns alter into ego albeit in the form of alter-ego. Hence Tom can take the place of Dickie, or in principle anyone else, in the same way that he can take McAlpin's position, or posit it. The Ripley novels are nothing but the possibility of that interchangeability—and the cultural techniques that enable it (the typewriter, the post, the telephone, the train, the passport, the newspaper, the telegraph, and the novel)—the techniques that presuppose addicts of the secondary (and their anaesthetic media). Or we might say that the epistolary novel (and Highsmith's novels are full of letters) has mutated: it now includes form letters too.

In short, in the reconstructed office world, and in the reconstructing official world, the act and its registration are two parts of single formation. But the parts are first separated via a legal-technical process and then recombined as, precisely, the process of administration. And that combination of statement and practice here takes the form of a practical joke, a merely official world.

It is not just then that "[t]he registration and revelation of reality make a difference to reality. [That it then] becomes a different reality, consisting of itself plus its registration and revelation." 37 The official world—that is, a modern self-generated and self-described world—is one that works via a continuous transfer of the act and its registration. It takes shape in taking into account and storing its own actions. 38

The IRS for Highsmith is then, like the INS for McCarthy, a sort of practical joke. One with, as they now say, existential consequences. The practical joke is a self-induced and self-exposed game about being taken in by games, and the observation of that process. It is a centauric form, one that (like the bureaucratic medium) combines a physics and a hermeneutics. (It is located on the switch-point of the physical act, and its registration and observation, such that each indicates the other.) It does so with the intent of causing embarrassment—a sociable moment, a little space of commitment—felt on the body. Hence it provides a scale model of the interactive rituals, or drills, of the daily planet.

The practical joke is one of the calisthenics of social-interaction rituals by which make-believe makes belief and then discredits it, breaking what Erving Goffman calls "a socialized trance." Embarrassment or, rather, the observation of embarrassment—and its observed self-observation—is its object. 39

The practical joke is thus a game that gives itself away in the end, since its purpose is to see whether the other person believes in the game or not. More exactly, it posits, as its formal condition, the little social system constructed "between the concealer and the concealed-from" (103). (It plays a game of hide-and-seek that excludes one player, from whom the game itself is hidden). It stages a small world and then proceeds to discredit it by exposing the credulity that holds it in place—showing that one (the concealed-from one) has been taken in by taking the game as serious or real. But the point is not merely to embarrass the true believer. The point is to show his becoming-embarrassed over his embarrassment: to mark the point "when, in short, the interactive world becomes too real for him" (123). 40

The physical symptoms of embarrassment, the "objective signs of emotional disturbance," make up a long list: they include "blushing, fumbling, stuttering, an unusually low- or high-pitched voice, quavering speech or breaking of the voice, sweating, blanching, blinking, tremor of the hand, hesitating or vacillating movement, absentmindedness, and malapropisms" and so on (97).

These disturbances—which are, for the most part on this account, disturbances in communication (speech and signal)—are the bodily registers by which "the standards of the little social system are maintained through the interaction" (106). They are means by which its rituals of self-evaluation and self-propitiation are at once represented and presented. 41

That's clear enough, for instance, in those games that "commemorate the themes of composure and embarrassment" (104), like poker or spectator sports or reality TV. The embarrassing incident tests outs how the "interaction qua interaction" is proceeding, making things "safe for the little worlds sustained in face-to-face encounters" (118). 42 There is a good deal more to be said about the repercussive character of these situations. 43 For now I mean to indicate the manner in which the reality tests like the practical joke, or sport, or (in fact) the artwork test out controlled and uncontrollable bodily states: these conduct social experiments, under outlined, repeated, and staged conditions, not least in the forms of identification (controlled, or uncontrollable) solicited in literary fiction. These are Highsmith's own renditions of an international necronautical society, and its demarcation zones, its games, crimes, and art. These "little worlds" epitomize the autotropic social systems of the daily planet—or what Highsmith also calls (the title of her 1958 novel) "a game for the living."

The Uncanny Valley

Highsmith's experimental novels observe the behavior and interaction of human beings in their glass cells—strange captives in an imaginary zoo. 44 These novels are clinical reports on a wound culture and its pathological states (at times, as in Ripley's Game, clinical reports in literal terms). They are reports on species physiology, its ouroboric reflexivity, and its bent toward technical life. 45

A certain way of sensing and reporting the world makes it possible to observe, for example, "the caviar [tossed in a fire], popping like little people, dying, each one a life" (ST, 116). To speak in terms of a character "different from...any other human" (ST, 19). To see a little turn in one's course of action as something "like the turning of the earth" (ST, 281).

This imaginary zoology is thus suspended between history and natural history, biology and its administration, unnatural and natural disasters. It includes "mermaids on the golf course." It includes an island of giant naturalist-devouring molluscs. It includes stories of "bestial affinities" (ST, 144)—snail-keepers fascinated by the sexual life of these backyard aliens and their capacity, or talent, to move across the upturned blade of a razor (a fascination Highsmith shared); or perpetually floodlit chicken factories that generate a hothouse madness and horrific violence. It includes too an unearthly human order routinely described in terms such as these: "Some wisps of hair, darkened brown with sweat, bobbed like antennae over his forehead." 46

The fat words "life" and "society" and "world"—especially "world"—repeat in Highsmith's writings with an unyielding abstractness. This is life viewed (the examples here are from Strangers on a Train), as it were, from "another planet" (54). It is viewed in terms, again and again, of "the outside world" (18), "the whole world" (132, 155, 247), "its own world" (26), "the pulse [of the] world" (232) "the new world" (38), "everything in the world" (54), "as if the crust of the world burst" (151), and so on.

But it's not hard to see the ease with which that grandness of reference overturns into grandiosity of self-reference, "the outside world" to "someday Guy and I are going to circle the world like an isinglass ball, and tie it up in ribbon" (260) to "take on the whole world and whip it!" (262). In effect, alter and ego, "Guy and I are Superman."

Superman, who could, on a good afternoon, easily remedy world-wide problems of war, poverty, disease, and all the rest, instead divides his time between his reporting job and catching petty criminals in a big Metropolis that's still then Smallville, USA. 47 There's a performance of scale here. The evocation of the vastnesses of deep space or time largely functions as evocation. There is perhaps an element of the sublime in this, its apotropaic rhythm, and its counter-effect of self-aggrandizement. But my sense is that this is less a matter of the sublime than of the autotropic conditioning of a modernity at once self-inciting and self-reporting, continuously re-using reference as self-reference, and so setting off the reflexes of a reflexive modernity, albeit at its meridian. 48 Reference becomes self-reference, seeing self-seeing, observation self-observation, locating self-locating. 49 We are in fact very familiar with this way of seeing a world or, at the least, with the diagrammatic and simplified visual techniques that lend themselves to it. A little sampling from Highsmith's Strangers on a Train: "the world beyond the merry-go-round vanished in a light-streaked blur" (77); "the oblique bars of shadow" (177); "two streaks of red fire that came and disappeared" (167); "a small room lined in red" (200); "Bruno's mouth a thin, insanely smiling line" (194).

This is the worldview of the every-guy architect Guy who draws alternate worlds into existence in his office space—"floor models" and "cartoons" of what a building or city might look like (and hangs a drawing of an imaginary zoo on his bedroom wall). And these are the lined and simplified comic-book worlds that Highsmith drafts and scripts, at the typewriter and storyboard, in hers: faces of invading and alien realities but also the look of a daily planet that is immanently unearthly. Its nonhuman figures are outlined like humans, ones who are near but also far—like strangers, with bobbing antennae, on a train. This is a stranger-intimacy with (as Bruno is introduced in Strangers on a Train) "a look that was eerily omniscient and hideous...this thing right in the center of [his] head." This is the alien as usual, albeit (with apologies to Tom McCarthy) more usual than usual. 50

"A constellation of red and green and white lights hummed southward in the sky" (ST 11). The constellation is not in fact the distant stars but a series of signals, a coding system, marking and reporting the moving perimeter of the zoned world (the hum of the daily planet, demarcated and encircled, the planet in effect as planetarium.) There is, as it were, a condensed history of modernity in passages such as this one, or in the world vanishing behind the light-streaked blur of a rotating model of one. Suffice to say that the passage—in its shifting from the planetary to the daily planet (from constellation to a human order of things)—invokes in order to revoke the turn to the great outside. That's what the speculative realist Quentin Meillassoux describes as the loss of Great Outdoors—le Grand Dehors—and hence "the impossibility itself: to get out of ourselves" and our limitation to a world that "exists only on the basis of a vis-à-vis with our own existence." 51 This is the two-step by which the turn to the great outside is coupled to the counter-turn of a modernity premised on its observation. ("A curious analogy," Wittgenstein notes, "could be based on the fact that the eye-piece of even the hugest telescope cannot be bigger than our eye.") In short: in Brecht's play Galileo, it is announced, in turning the telescope from the earth to the big sky: "January, 1610. Heaven abolished." The counterrevolution, at its limit, makes for Virginia Woolf's statement that "in or about December 1910 human character changed." We might tentatively add that on or about January 2010, the call of the wild, the great outdoors, was heard again. And that already a half-century after Foucault, in the last paragraph of his archaeology of seismic shifts in Les mots et les choses, concluded that the brief period of the human character of things—not millennia-old but a narrow interval from the late eighteenth century to the mid-twentieth—was coming to an end: the disappearance of the face of man drawn in sand at the edge of the sea. A scene literalized—in the little exchange about letters that might be written in sand on the edge of a dead ocean—in McCarthy's The Road. The "anthropocene" has recently come to brand-name the epoch, not least in that it posits at the same time the generalization of the man-made and its incipient nullification: Brecht's rabbit holding seminars on the hopeless fix it has placed itself in.

I have elsewhere set out how Highsmith's work pivots on this condition: on the absolute decoupling of the world as it looks to us (our "indoor" social life) and the world as it looks without us (the Great Outside)—and on the horrors, and pleasures, that decoupling induces. For one thing, Highsmith's narrative way of seeing—preemptive and autistic—lends to self-observation the look of omniscience and to the counterfactual the feel of objective description. For another, uncontrollable identifications determine the semantics of character and interaction in these novels. In short, we see again and again a reflexive violence that (in these reiterative terms) tears the body to pieces, and then reorders pieces into parts and parts into the two parts of a whole, the twin halves of an identity. 52 There is a generalized failure of distinction between subject and space that is at the same time a failure of self-distinction: "The bathroom walls had that look of breaking up in little pieces, as the walls might not really have been there, or he might not really have been here" (ST 200). Self-observation proceeds in just these terms (which are not metaphoric but descriptive)—such that alter enters into ego but in the form of alter-ego, and so as a process of continuous "self-annihilation." (This is a refrain, for example, in Strangers, The Talented Mr. Ripley, Those Who Walk Away, and so on—the disincarnations of identity that are characteristic of Highsmith's work. A state of hypertrophied reflexivity uncorrectable by external information—and so a correlate of reflexive modernity, and its strict delimitation of the world to its self-observed observer. Reflexive modernity with a human, or nearly-human, face).

These are the intensified and denuded simplifications of character and ground in this work—and we should be familiar with these outlines. In his immensely useful account of forms of figure and ground in the art of comic books, Scott McCloud traces how, in comics "most characters were designed simply, to assist in reader-identification." 53 Here think of the simplicity of the emoticon (or for that matter their reproduction on the faces of those viewing them, on their smartphones, for their viewers :-)). For McCloud, they are designed to assist in identification and self-identification—"just as our awareness of our biological selves are simplified conceptualized images" (39). In short (and in terms that resonate with the account of the cellular organization of modernity I have been setting out here): "when you look at a photo or realistic drawing of a face—you see it as the face of another...the world outside of us... But when you enter into the world of the cartoon—you see yourself...the world within" (40-41). The simplification of representation in the direction of line and outline means that "those same lines became so stylized as to almost have a life and physical presence all their own" (111).

McCloud's account is more complicated, but the point is that the diagrammatic in this art form lends itself to a readiness of identification, such that "we make the world over in our image": "we see ourselves in everything" (33).

The drive to identification here has a real counter-side, however. For one thing, the intrusion of realism (a realism relative to line or diagram) interrupts or spoils it. The deviation from line and outline into irregularity, or asymmetry, not merely interrupts but overturns that identification. This is the moment when the stylized "body-to-body analogies" (I will return to this way of putting it in a moment) that make identification possible mutate, and become images of just the opposite.

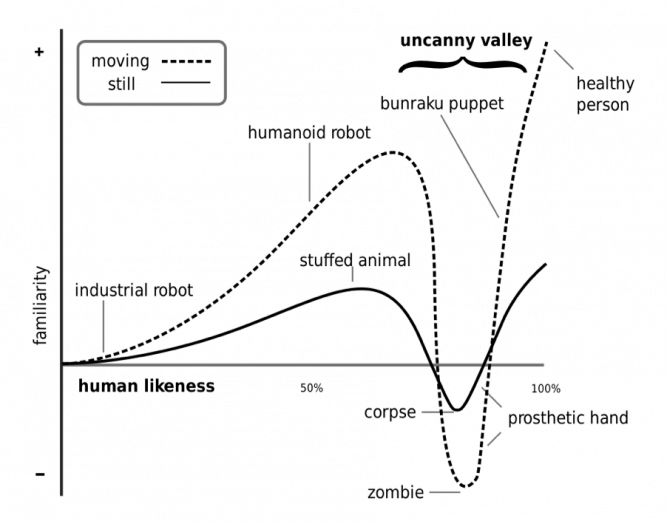

These figures inhabit what robotics engineers, from the 1970s on, call "the uncanny valley"—that abrupt transit point in realist representation at which identification with the simulation of human face or body abruptly reverses into revulsion, and the nearly human overturns into the barely human. The uncanny valley charts that moment when the incitation to identification (via say puppet or clown or doll) becomes horrific. Here it's perhaps appropriate, in the account of these living diagrams, to let the diagram stand in for a more extended explanation:

The moment of the uncanny valley is the moment when over-identification turns inside out. The zombie, it will be seen, moves and lives, or persists, at the bottom of the uncanny valley. The walking dead, motion without life, undoes the fundamental principle (as Hobbes expressed it) that "life itself is but motion." Hence the simplified analogy between bodies upon which identification is founded becomes too real to be sustained. These are the formal conditions for the uncontrollable identifications—and disidentifications—we have seen setting out. They are too the preconditions for self-conditioning and autotropic practices like novel-reading—and its excitations—in the first place.

Coda: The Loyalty Card

There is a party, everyone is there

Everyone will leave at exactly the same time

When this party's over, it will start again

It will not be any different, it will be exactly the same

Heaven, heaven is a place, a place where nothing, nothing ever happens.Talking Heads, Heaven

"The novel itself had found its leitmotifs in the bodies of its protagonists," Niklas Luhmann notes in The Reality of the Mass Media, and did so "especially in the barriers to the controllability of bodily processes." The dominance of dangerous or erotic adventures in the novel is explained, he further suggests, in that they provide ways "in which the reader can then participate voyeuristically using body-to-body analogy": the "tension in the narrative is 'symbolically' anchored in the barriers to controllability in each reader's body." 54 It's not simply then that readers imitate characters in novels. Instead, they enter into situations of incitation and their observation—which is to say, situations of self-incitation and self-observation. 55

The complement to novel reading, on this account, is the boundary condition of bodily control to be found in the viewing of sporting events. Such events, to the extent that they are intended for spectation, provide body-to-body analogies too. The sporting event then provides not merely occasions for excitation by proxy but fitness to a reenacting, risk-driven, and self-reporting world.

Highsmith's novel The Talented Mr. Ripley, for example, pivots on the observation of a "game" that involves the body-to-body building of a "human pyramid"—a game, a spectacle, and a form—and it is this scene that stimulates Tom's first killing. 56 The suspense novel—the form of the human pyramid is the very model of suspense, the suspension of bodies in the name of some superior form—stages that suspense: it provides a narrative of ungovernable copying and the self-incited, physical thrill of risk-taking and serial games of self-endangerment. It is not merely that Tom is everywhere "still pretending, uncontrollably" (165). The novel does the same. Ripley's games—in the border zones of controllability and its panic/thrill—are then the formal conditions for novel reading and analogues of it: these forms of copying are copied into each other.

The analogues at work in moments such as these are technologies of auto-stimulation. Their internalized character makes it possible for the space of the game, the scene of the crime, and the work of art to refer back to each other in circular fashion—and so provide the conditions for the continuous rotation of the elements of a self-induced world.

In his recent account On Deep History and the Brain, the historian Daniel Lord Smail traces in some detail the emergence and spreading of autotropic commodities from the long 18th-century on: self-stimulants such as alcohol, caffeine, chili pepper, opiates, tobacco, chocolate, sugar, gossip, sports, music, new media, religiosity, recreational drugs, sex for fun, and pornography. Last and not least—or most—is novel-reading and related forms of literary leisure: what in the nineteenth century came to be called a reading world. These are versions of what one contemporary observer calls "the controlled use of the uncontrollable." 57

Here is the biological component of that self-incitation. Smail is entranced by the example of the snorting horse: "Horses who get bored or lonely while isolated in a paddock sometimes take pleasure in startling themselves. A lively snort causes a chemical feedback that induces a startle reflex and an exciting wash of neurochemicals." He, the horse, mimics the conditions that would naturally stimulate a startle reflex. For Smail, this feedback pleasure is like the self-stimulative history he traces, with the difference, of course, that "the horse cannot say to himself, 'I feel like getting startled'" or report that thought to others. Hence the autotropic world is between history and natural history (at once deep history and deep history). 58

I have been suggesting here that this oscillation between the planet and its reporting is one way of marking the difference between a modern age and the modern world—a world trending toward the automation of everything and toward the self-organization of everyday life on the daily planet. In the official world, positions—planning, rehearsing, staging, recording, commentating—run in a continuous loop, each reinstating the other. The repetition-automatism (trauma), the figure 8 (for instance, in McCarthy's Remainder), stand-alone and autoreferential form: these are its primary shapes. Here we are reminded that, as Diedrich Diederichsen puts it, the endless loop has become the contemporary rhetorical figure par excellence: "the reason the loop became such a successful rhetorical trope in the effort to describe, narrate, and even organize experiences is that it harbours possibilities ranging from regression to self-reflection without ever becoming arbitrary: a conspicuous constellation that subsumes ever more (sub)cultural territory, organizing very different things that would have otherwise been mere narrative. And no one really trusts narrative anymore." 59

It's not possible at the moment to take this account further. But since the work of one of this world's most alert recent reporters, the novelist and choreographer of officialism, Tom McCarthy, has run like a thread through these pages, it may be appropriate to give the General Secretary of the INS the last word, even if it is not exactly his. This not least in that his work describes and indexes the circuitry of an auto-inciting and re-enacting worlds. Here is a look at that world in operation: a conversation of sorts between the novel's commentator (who describes himself as a "robot or zombie") and a couple of the daily planet's actors, or re-enactors (who describe themselves in the same way—"Sorry! I'm a zombie! [116] too)—and at one of its iconic sites:

After a while I tired of watching all these amateur performances [that is, people interacting on the street] and decided to buy a coffee from a small concession a few feet away. It was a themed Seattle coffee bar where you buy caps, lattes, and mochas, not coffees. When you order they say Heyy! to you, then they repeat your order aloud, correcting the word large into tall, small into short. I ordered a small cappuccino.

"Heyy! Short cap," the man said. "Coming up! You have a loyalty card?"

"Loyalty card?" I said.

"Each time you visit us, you get a cup stamped," he said, handing me a card. It had ten small pictures of coffee cups on it. "When you've stamped all ten, you get an extra cup for free. And a new card."

"But I'm not here that often," I said.

"Oh, we have branches everywhere," he told me, "It's the same deal"....

If I got all ten of its cups stamped then I'd get an extra cup—plus a new card with ten more cups on it. The idea excited me.

The loyalty card is a little technology that blueprints, comments on, and records what it does, and it reinstates itself as it goes. Not only that, it incites loyalty—that is, reenactment—in the process. And that's, as the nameless narrator puts it, "the beauty of it. It became real while it was going on." 60

Mark Seltzer teaches English at UCLA.

References

- #1 Clive Barker, introduction to The Sandman: The Doll's House, by Neil Gaiman (DC Comics, 1990), not paginated.[⤒]

- #2 See my "Parlor Games: The Apriorization of the Media," Critical Inquiry 36:1 (Autumn 2009): 100-133; "Die Freie Natur," in Gefahrensinn: Archiv für Mediengeschichte (München: Wilhelm Fink, 2009), 127-38; "The Official World," Critical Inquiry 37:4 (Summer 2011), 724-53. See also, on Highsmith, "Vicarious Crime," in True Crime: Observations on Violence and Modernity (New York: Routledge, 2007), 111-38. [⤒]

- #3 Patricia Highsmith, Strangers on a Train (1950; New York: Norton, 2001), 26.[⤒]

- #4 Tom McCarthy, Remainder (New York: Vintage, 2007), 185[⤒]

- #5 I am quoting Bernhard Siegert, "There Are No Mass Media," in Mapping Benjamin: The Work of Art in the Digital Age, eds. Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht and Michael Marrinan (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 38.[⤒]

- #6 See Joan Schenkar, The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2009), 157.[⤒]

- #7 Highsmith, Strangers on a Train, 261. My thanks to Tom Perrin for reminding me that Bruno is a reader of comic books (see ST, 14).[⤒]

- #8 See W. G. Sebald, "Between History and Natural History," in Campo Santo, trans. Anthea Bell (Modern Library: New York, 2005), 65-96; and Sebald, On the Natural History of Destruction, trans. Anthea Bell (Modern Library: New York, 2004). What is set out in Sebald's account is not a biological explanation for social forms of life (or their "naturalization") but instead the incoherence of the antinomy in the first place. That incoherence becomes explicit above all (it will be seen) in episodes of catastrophic modernization—episodes in which, as Kluge puts it, those affected "could not have devised practicable emergency measures...except with tomorrow's brains." [Alexander Kluge, Neue Geschichten: Unheimlichkeit der Zeit (Surhkamp: Frankfurt, 1977), 53.][⤒]

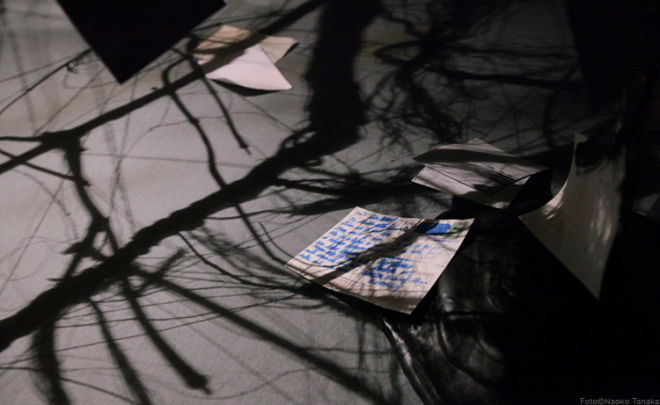

- #9 The presumption of the reciprocal conditioning of each by the other (positive feedback)—generalized now to mean sort of "everything is connected"—has lessened interpretive pressure on the dilemmas the duality is designed to address. (Hence it has generated terms, like "intersectionality" or "relationality" or "connectedness," that name or brand-name what is in effect a black-boxed business as usual.) The coalescence of many of these issues of social and natural history around the large term "affect" has made for similar naming-events and non-sequiturs. (My sense of these matters has been inflected by the brilliant installation/performance work of Naoko Tanaka, Absolute Helligkeit, presented at Performance Platform: Body Affects, Berlin 5-8 July 2012.)

[⤒]

- #10 We can punctually date the emergence of a self-describing society with the appearance of its scribes: the advent of official self-description in the rise of sociology and the first sociologists, the field reporters of a daily planet. On self-describing modernity, see, for example, Niklas Luhmann, "Deconstruction as Second-Order Observing," in Theories of Distinction: Redescribing the Descriptions of Modernity, ed. William Rasch (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002), 94-112.[⤒]

- #11 Stanislaw Lem, Imaginary Magnitude, trans. Mark E. Heine (Orlando: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984), 131.[⤒]

- #12 See Cornelia Vismann, Files: Law and Media Technology (Stanford, 2008) [⤒]

- #13 I draw here on Niklas Luhmann, Art as a Social System, trans. Eva M. Knodt (Stanford, 2000). The question then, of course, is whether the consideration of "art as a social system" is adequate to the consideration of the work of art. I take up this question here in terms of the crisis of the artwork in the epoch of social systems. (The question then, on another level then, is whether social systems theory provides a good account of these matters or a good symptom of them. On this, see "The Crime System," in Seltzer, True Crime: Observations on Violence and Modernity, 57-90.) [⤒]

- #14 On the manner in which social systems stage their own unity, see (in addition to Luhmann) Problems of Form, ed. Dirk Baecker (Stanford, 1999), particularly Baecker's "The Form Game," 99-106; and Elena Esposito, "The Arts of Contingency," Critical Inquiry 31:1 (Autumn 2004), 7-25.[⤒]

- #15 The ongoing oscillation between checking and acting—and hence the unity of the distinction between them—is set out in Norbert Wiener's account of majority and minority reports in his foundational Cybernetics: or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1965), 145; it is the direct source of Philip K. Dick's Minority Report, in which this common principle is recognized, albeit anthropologized. Self-reporting is not something added to the sequence of operations, but rather that sequence works through self-reporting. Self-reporting is its condition of operation and a generalized one: as Wiener goes on to say: "Like the computing machine, the brain probably works on the principle expounded by Lewis Carroll in The Hunting of the Snark: 'What I tell you three times is true.'" (It is perhaps worth noting that if then literature and biology have a self-reporting principle in common, this common principle scarcely provides the basis for the claim—promoted in a range of recent accounts of literature and biology—that the first is an effect of the second and so indicates the insistence of bio-evolutionary components in literary forms. This is a bit like arguing that, since both steam engines and Proust have a way of recollecting past states, Remembrance of Things Past is steam-powered.) [⤒]

- #16 Dirk Baecker, "The Form Game," in Problems of Form, 106. Just as in spectator sports, one must repeatedly reenact the distinction between the inside and the outside of the game, which is then copied into the game. It is necessary to distinguish between what is inside and outside the lines, to take note at every moment of what is, say, inside and outside the zone, between time in and time out, between live and dead balls, between game space and spectation space, between act and record, score and standings, and so on. These are its strike zones of demarcation and reenactment, administrative zones, it is true, but the administrative a priori must then be understand in this expanded form. The expansion and realization of its zones is one marker of the transition from a modern age (which knows this) and a modern world (which enacts it, and so is almost sui generis). The question is whether, as, for example, Tom McCarthy's Remainder puts it, these demarcation zones are now "nonexistent" or "limitless"—which would, of course, amount to the same thing (283). [⤒]

- #17 The description is Quentin Meillassoux's in After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency, trans. Ray Brassier (London, 2008).[⤒]

- #18 Brecht, as cited (loosely) in Sebald, Campo Santo, 89.[⤒]

- #19 We may recall (not least in the context of the biological and neurobiological turn in recent literary studies) that Zola's program for the experimental novel in the Rougon-Macquart series makes this explicit, from the descriptive subtitle of the series on—Histoire naturelle et sociale d'une famille sous le Second Empire—advertising the unity of the distinction between history and natural history in naturalism. Zola, Oeuvres complètes, ed. Henri Mitterand (Paris, Cerce du Livre précieux, 1966-70). See also n. 22 below.[⤒]

- #20 The first phrase appears in Highsmith's Strangers on a Train (1950; New York, 2001), 143; subsequent references in text. For the second, see Highsmith's captivity (or self-captivity) narrative The Glass Cell (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964).[⤒]

- #21 Sebald, Campo Santo, 77. One finds too, in Sebald's divagating and searching fiction, something like the pathos of the search engine, with all its safaris and explorers, and sites of lost or sought things. This may be one of the strange attractions of Sebald's work today. (We might compare here the sense of taking stock of a used world in Cormac McCarthy's The Road. Or even recession reality shows like The Antique Roadshow, in its lost-and-found revelations of history and value. On The Road, see n. 24 below.) [⤒]

- #22 It would be necessary, in a fuller account, to pressure not merely the presumption of social constructionism that's currently going out of vogue but also the counter-turn to biology in the humanities and social sciences that's coming into it. The return to biology and natural history in literary and social studies today has taken on an optative, even peppy tone: at its weakest, species life as the family of man. This tone often amounts to the evocation of deep time and space as mere evocation—and in the service of a strictly intramural conservativism. In this way (it will be seen) evocation of the deep history of the planet programmatically overturns into microhistories of literary institutions. (The institution of literature thus appears as something like a little house on the cosmic prairie.) Along these lines, the Great Outside is invoked but in effect as a circular detour that returns us to our indoor life: reference into self-reference, seeing into self-seeing, location into self-location. [I am here drawing on Joseph Vogl's "Becoming Media: Galileo's Telescope," Grey Room, Fall 2007, No. 29, 14-25. See also n. 40 below.] This is the reflex of an autotropic and official world. I have set out what this looks like (with particular reference to speculative realism, and the work of Quentin Meillassoux) in "Die Freie Natur," Archiv für Mediengeschichte. I will return to some of its implications, and paradoxes, in the final section of this paper. Here we may simply note that one need not evoke deep time and vast space in order to see, for example, high modernity and the hunting-and-gathering stage of species life side-by-side: one might instead, say in Berlin or Tokyo on a day in 1945, or in Sendai a year ago, just step outside. [⤒]

- #23 Max Brooks, World War Z: An Oral History of the Zombie War (New York, 2006), 4-5. I thank, or forgive, my teenage son for directing my attention to this novel. On the spread of zombiedom in the humanities, and culture at large, see: Mark McGurl, "Zombie Renaissance," n+1 9 (26 April 2010); and Better Off Dead: The Evolution of the Zombie as Post-Human, eds. Deborah Christie and Sarah Juliet Lauro (New York: Fordham University Press, 2011).[⤒]

- #24 This suspension is the "cauterized terrain" of Cormac McCarthy's post-apocalyptic novel, The Road. The world has been contracted to a father and son—"each the other's world entire"—who push down the road a battered shopping cart, containing their bare provisions, in a thoroughly consumed world—as if going down the same road that led to the disaster in the first place. It is (and here I am paraphrasing Kluge's account of the devastation produced by the air war on Germany) as if the reflexes of a form of life that not merely preceded the disaster but led to it continue on in the absence of the obliterated world that was the prerequisite for them. And prerequisite for the form of the novel itself. The world of The Road is one virtually stripped of secondary qualities: "some cold glaucoma dimming the world." It is a world stripped of self-observation and so of news of itself. There remain only the remnant small technologies—binoculars, map, lamp—that not merely locate a way of seeing but ways of seeing: the world as it looks to us. The sudden, quenching return of color and life, in the last lines of the novel—and the beauty of "the deep glens where they lived all things were older than man"—appear strictly in terms of the world as it looks without us. The Road is thus located at the crossroads of a speculative realism and a social realism. It is located, that is, at the crossroads of two world views, or, more exactly, a worldview and a world without a view. First, the nature of things apart from us— and apart from how we see them (cold, autistic, alien, uncoupled, implacable, a world unheard of—these are some of McCarthy's terms for this). Second, the remnant flashes of a social realism and its prerequisite idiom of a mutually observed and self-reported world—that is, the world of the novel at its meridian, or eclipse. (The Beckett-like exchanges between the father and son that involve idioms shorn of their referents—"What are our long-range goals?"; "The odds are not in their favor," etc.—posit an unobserved and unobservable world, one in which there is no one to signal to.) To the extent that the novel (as the way of the world) correlates the world and its observation, The Road indicates the world of the novel at its eclipse. The correlation of the world and its observation is the presupposition of social systems theory (which collates at every point the world and its reporting, such that the reporting of the news is the news reported on). It is precisely the paradoxicalization of this correlationism which has entered into crisis today (for example, in novels such as The Road or, along very different lines, Sebald's testing of the boundary lines of history and natural history—in fiction like The Rings of Saturn, or history like Campo Santo). McCarthy's dispositif of the secondary and primary qualities of the world of the novel is another way of staging the crisis of correlationism (that is set out in philosophical terms by Meillassoux, and in speculative realism more generally). On the distinction between the world as it looks to us and the world as it looks without us, in No Country for Old Men, see my "The Official World," Critical Inquiry.[⤒]

- #25 This the title given to Highsmith's collection of short stories first published in 1987 (Tales of Natural and Unnatural Catastrophes [London: Bloomsbury, 1987]).[⤒]

- #26 Sebald, Campo Santo, 95. Or, as Sebald expresses it elsewhere, in On the Natural History of Destruction: "Is the destruction not, rather, irrefutable proof that the catastrophes which develop, so to speak, in our hands and seem to break out suddenly are a kind of experiment, anticipating the point at which we shall drop out of what we have thought for so long to be our autonomous history and back into the history of nature?" (66).[⤒]

- #27 See "The Radical Ambiguity of Tom McCarthy," interview by Clodagh Kinsella, Dossier (July 25, 2009). [⤒]

- #28 "Re-enactment brings about a kind of split within the act itself...on the one hand it's something you do, and on the other it's not something you're actually 'doing': it's a citation, a marker for another event that this one isn't." (McCarthy, quoted in Simon Reynolds, Retromania: Pop Culture's Addiction to Its Own Past [New York: Faber & Faber, 2011], 54). This citation—this one—reminds you that events are possible, and only because they happened before.[⤒]

- #29 "Gebet mir Materie, ich will eine Welt daraus bauen! Das ist, gebet mir Materie, ich will euch zeigen, wie eine Welt daraus entstehen soll" (see Kant's Preface to his Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels). Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 295.[⤒]

- #30 "Manifesto of the Necronautical Society," accessed 16 November 2012.[⤒]

- #31 See Saul Bellow, Dangling Man (1944; New York: Penguin, 1998), 10.[⤒]

- #32 On the reconstruction of Berlin in these terms, see my "Berlin 2000: 'The Image of an Empty Place,'" in After-Images of the City, eds. Joan Ramon Resina and Dieter Ingenschay (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003), 61-74[⤒]

- #33 McCarthy, Remainder, 93.[⤒]

- #34 Patricia Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955; New York: Vintage, 1999), 14-15.[⤒]

- #35 Highsmith, The Talented Mr. Ripley, 20. The uncanny space of "the office" epitomized for a period (roughly a century) the demarcation zone of a self-denoting world. The administrative a priori—along with the oddity of a form of life (bureaucracy) that takes its name from a piece of furniture—has been mapped in detail from Weber to Adorno, and its operations filled in more recently by accounts of the little cultural techniques of this habitat (files, index cards, typewriters, ring binders, perforation, staplers, copy-paper, etc.), techniques that appear as epoch-making as the plow or stirrup. At its advent there is Flaubert's very early story (1837), written at the age of fifteen, "A Lecture on Natural History—Genus: Clerk." premised on "my frequent trips to offices...You ought to see this interesting biped in the office, copying its register ..." (Flaubert, Early Writings, trans., Robert Griffin [Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991], 45-49.) At its mid-point, consider the opening chapter of William Dean Howells's The Rise of Silas Lapham (Edinburgh: Davis Douglas, 1885). The opening does not merely inventory the appliances, partitions, occupants, and distinctions of this space. It makes visible the manner in which the indoor techniques of recording and self-recording become the terms of a world. The novel opens with an interview in an office but an interview that is described, recorded, and reported, as it takes place—such that (via a cut-and-paste in diegetic time) the event and its registration enter into each other at every point. More than that, the world outside the office—space "indoors and out"—denotes and depicts itself too. Hence the outside world is a self-demarcating one: in one example after another after another, we find the street stones scored and "worn by dint of ponderous wheels...and discoloured with iron-rust from them"; "here and there in wandering streaks over its surface...the grey stain of the salt water with which the street had been sprinkled"; and "at the end of one [at the very edge of a self-constructing world—"block and tackle wandering into the cavernous darkness overhead"] the spars of a vessel penciled themselves delicately against the cool blue of the afternoon sky." Everything acting is in the act of delineating itself. The point not to be missed is that the presupposition and condition of realism is not the description of every thing, but the description of the self-description and self-indexing of everything. If Howells's novel has been taken to epitomize realism, it does so then because it epitomizes a self-epitomizing world. (Hence if we are meant to hear—in the name of Howells's reporter/interviewer Bartley Hubbard—the name of the office-dweller Bartleby, we are meant too to see not merely the dead zone of mechanical reproduction but, beyond that, the emergence of an autotropic control network, coterminous "indoors and out," what Howells calls "another world.") (All references to the first chapter of the novel.) [⤒]

- #36 "I have a position" is the refrain of Dreiser's novel of the new lines and places of the official world, Sister Carrie (1900). Carrie herself is above all a "carrier": the first paragraph of the novel is a virtual inventory of things designed to carry other things—from the suitcase or wallet or lunch box or envelope to the train car itself—and Carrie is of course a medium, a carrier and mode of conveying the world's longing—just as the city of Chicago itself is a place that is not exactly a place, "not so much thriving upon established commerce as upon the industries which prepared for the arrival of others." Sister Carrie (New York: Norton, 1970), 11. Things hold the places of other things, and places are placeholders.[⤒]

- #37 See Dirk Baecker, "The Reality of Motion Pictures," MLN: Modern Language Notes 111:3 (1996), 561.[⤒]

- #38 See Cornelia Vismann, "Out of File, Out of Mind," in New Media/Old Media: A History and Theory Reader, eds. Wendy Hui Kyong Chun and Thomas W. Keenan (Routledge: New York, 2006): "files display a rather complicated duality"; hence "the simple equation between files and the world, between the physicality of storage and the existence of data in the order of signs," 119-28.[⤒]

- #39 See Erving Goffman, "Embarrassment and Social Organization," in Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face-to-Face Behavior (Chicago: Aldine, 1967), 97-112. (Subsequent references to Interaction Ritual in text.) [⤒]

- #40 The social obligation is to "keep things going." Hence over-involvement is as much "a crime against the interaction" as dis-involvement. The interaction hero avoids both in his performance of spontaneity.[⤒]

- #41 The self-conditioned and self-evaluative character of contemporary institutional work spaces is the normal condition of competitive socialization today, inside the "affective labor" of capitalism: as Diedrich Diederichsen expresses it: "Self-evaluation—a familiar ritual in today's universities and workplaces—is nothing other than a visible, public form of organized narcissism as higher-order repression." See Diederichsen, "Radicalism as Ego Ideal: Oedipus and Narcissus," e-flux (2011), accessed 16 November 2012[⤒]

- #42 For Goffman, it will be recalled, the matter of embarrassment in modern social situations "leads us to the matter of 'role segregation'" (108) or social differentiation. The scenes of embarrassment and of "joking and avoidance" that Goffman inventories are the scenes of an official and differentiated world—office buildings, schools, hospitals. Embarrassment takes place, more exactly, at the sites of a stranger intimacy in friction with that role segregation: places of embarrassed encounter like elevators, corridors, entrances, parking lots, or the coffee machine. Hence the executive elevator, like the stratified parking facility or the freight entrance, are embarrassment-avoidance devices, the built infrastructure of what Goffman likes to call a civil inattention.[⤒]

- #43 I take up these matters in the context of an account of the games, forensics, and the art in the writings of Agatha Christie in "Die Freie Natur," Archiv für Mediengeschichte.[⤒]

- #44 Ripley goes to the bar called The Green Cage at the start of The Talented Mr. Ripley; near the close of Strangers on a Train, the detective Gerard "poked a finger between the bars and waggled it at the little bird that fluttered in terror against the opposite side of the cage" (215). The novel, The Glass Cell, about imprisonment and its after-effects, names her world.[⤒]

- #45 The reference to Ouroboros is to Plato's Timaeus and the animal "made in the all-containing form of a sphere...he moved in a circle turning within himself."[⤒]

- #46 This last is Bruno in Strangers on a Train (19). "Mermaids on the Golf Course" is a short story, included in a collection with the same title (New York: Penzler Books, 1988), 11-26. Two of the lethal snail stories are "The Snail-Watcher" and "The Quest for Blank Caveringi," both included in Highsmith, Eleven: Short Stories (London: Heineman, 1970). The snail-fixated murder novel is Deep Water (New York: Harper, 1957). The story of factory-farmed chickens gone wild is "The Day of Reckoning," originally published in Highsmith's The Animal-Lover's Book of Beastly Murder, and reprinted in The Selected Stories of Patricia Highsmith (New York: Norton, 2001), 84-97. Hitchcock, it may be noted, invents and interpolates Bruno's little speech about "life on Mars," in the party scene of his film version of the novel. He stops short of the sentence John Carpenter gives to Natasha Henstridge in his Ghosts of Mars: "As soon as I get back I'm going to tell my superiors all about this fucked-up planet."[⤒]

- #47 See Umberto Eco, "The Myth of Superman," in The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts (Indiana, 1979), 107-127. Eco's account locates Superman in part in terms of what David Riesman, in The Lonely Crowd, called the "other-directed" as opposed to the inner-directed) individual—what Eco calls "a model of 'heterodirection.'" (Rev. ed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001). In these rapid alternations between the inside and outside of worlds, and between self-reference and hetero-reference, we might recall too Lem's statement that "your genuinely immediate world is the outside world"—"that body of yours, which to some extent obeys you, says nothing and lies to you" (Lem, Imaginary Magnitude, 175). [⤒]

- #48 The performance of scale (evocations of big space and deep time that do not proceed beyond the evocative) functions in much the same way in a range of recent literary history—in the service of disciplinary self-reflection. In this way the discovery of deep history, for example, is folded back into the history of institutions, or into the reflexive history of history. Here one might consider what art critics have recently described as "the New Institutionalism." This refers in part to what Wolfgang Kemp has called the "Betriebssystem Kurator"—the curator as operating system. (Nowhere more in evidence than in the recent Documenta 13, 2012.) These operations, in turn, mark the turn to the institution as a cross-referencing system (what is sometimes described as "interdisciplinarity"). Hence the curator as operating system "aims at stimulating discussion and dialogue with other fields of knowledge and is committed to...radical exhibition strategies." In this way reference becomes cross-reference, and cross-reference becomes self-reference, in curating a world. All under the banner of "political engagement" and "expanded programming." See Wolfgang Kemp, "Betriebssytem Kurator," in Kunst (June 2012), 6-11, part of the special issue "God is a Curator" (accessed November 16, 2012).

For an alternate account of this institutional turn in the art world, see Diedrich Diederichsen, On (Surplus) Value in Art (Berlin: Sternberg, 2008). (I will briefly return to this New Institutionalism in the final section of this paper, in part by way of Daniel Lord Smail's recent Deep History and the Brain.) [⤒]

- #49 I am here paraphrasing Joseph Vogl's "Becoming Media: Galileo's Telescope," Grey Room, Fall 2007, No. 29, 14-25. The turn from reference to self-reference is both the subject and form of Vogl's instructive piece (as it is in a range of media studies that turns from the object to the form of its observation). Or in the terms of the systems theorist Heinz von Foerster (who described himself as Wittgenstein's "honorary" nephew), "reality appears as a consistent reference frame for at least two observers." Heinz von Foerster, Observing Systems (Seaside, CA: Intersystems Publications, 1981).[⤒]

- #50 The current discovery of "counterfactuality" in history and fiction might attend to such moments in the ordinary life of the daily planet, which continuously involves acts recast by the presence of alternatives.[⤒]

- #51 See Meillassoux, After Finitude, 7, 27.[⤒]

- #52 See my True Crime, 111-32.[⤒]

- #53 Scott McCloud, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (New York, 1994), 44. Subsequent references in text.[⤒]

- #54 Niklas Luhmann, The Reality of the Mass Media, trans. Kathleen Cross (Stanford, 2000), 59.[⤒]

- #55 Embarrassment and, as we have seen, its self-observed observation, is only the version of those situations of self-incitation and self-observation which correspond most closely to everyday life; one cannot imagine the first two centuries of the European novel without it—what Edith Wharton, in House of Mirth, calls the "art of blushing at the right time."[⤒]

- #56 I take up this scene in greater detail in my forthcoming book, The Official World. To condense that treatment here, consider this passage:

Tom watched with interest as a human pyramid was building, feet braced on bulging thighs, hands gripping forearms...He stood still to watch the smallest one boosted to the shoulders of the centre man in the three top men. He stood poised, his arms open, as if receiving applause. Tom watched with interest as a human pyramid began building, feet braced on bulging thighs, hands gripping forearms. He could hear their "Allez!" and their "Un—deux!"

"Look!" Tom said. "There goes the top!" He stood still to watch the smallest one, a boy of about seventeen, as he was boosted to the shoulders of the centre man in the three top men. He stood poised, his arms open, as if receiving applause. "Bravo!" Tom shouted.

Tom looked at Dickie. Dickie was looking at a couple of men sitting near by on the beach.

"Ten thousand saw I at a glance, nodding their heads in sprightly dance," Dickie said sourly to Tom. (Talented Mr. Ripley, 86).