In July 1956, the Pennsylvania Bar Association Endowment (PBAE) commissioned a comprehensive study of "wiretapping practices, laws, devices, and techniques" in the United States.1 At the time, Pennsylvania was one of several jurisdictions in the country without a statute regulating eavesdropping. Members of the PBAE's Board believed that a nationwide fact-finding mission had the potential to help state lawmakers establish effective policies for police agencies and private citizens. The man appointed to direct the study was Samuel Dash, a prominent Philadelphia prosecutor whose stint as the city's District Attorney had given him a first-hand look at eavesdropping abuses on both sides of the law. Two decades later, while serving as Chief Counsel of the Senate Watergate Committee, Dash would see many of those abuses come full circle.

After receiving a $50,000 grant from the Fund for the Republic, Dash hired a team of part-time researchers to help complete the study.2 Their ranks included Richard Schwartz, a communications engineer at the University of Pennsylvania, and Robert Knowlton, a legal historian at Rutgers University. The group worked together for sixteen months in twelve different cities, consulting wiretap experts with direct experience in the field: police officers, law enforcement officials, district attorneys, judges, phone company employees, electrical engineers, private investigators, even convicted criminals. "Every person we interviewed was an eavesdropper himself," Dash recalled, "a person who either employed it, authorized it, or actually engaged in installing the tap. . . . [W]e got our information right from the people who knew most about it."3 Dash himself interviewed more than 300 individuals over the course of the investigation. Only a handful agreed to go on the record.

The result of Dash's efforts was The Eavesdroppers, a 483-page report co-authored with Knowlton and Schwartz. Rutgers University Press published it as a standalone volume in 1959. The book uncovered a wide range of privacy infringements on the part of state authorities and private citizens, a much bigger story than the PBAE had anticipated. While law enforcement agencies were tapping lines in flagrant violation of state and federal statutes, phone companies were deliberately underreporting wiretap statistics to maintain public confidence in their services. While American businesses were stockpiling equipment to spy on employees and gather competitive intelligence, private investigators were using frightening new tools to listen in on wayward lovers and loose-lipped politicians. As Dash told members of Congress on the eve of the book's release, the American public's longstanding disregard for threats to communications privacy had only served to exacerbate these developments. "[T]he context of this whole subject clearly shows that we are not dealing with a new problem," he testified to the Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights in July 1959. "We are dealing with a problem that is at least 100 years old. At least from the very beginnings of electronic communication there were interceptions of electronic communications. Each generation seems to forget the problems of the past and considers this their own unique problem."4

The Eavesdroppers ended up having an outsized influence on popular debate. According to the legal scholar Alan Westin, whose own book on the subject, Privacy and Freedom (1967), made extensive use of Dash's research, the American public's attitude toward wiretapping had drifted ambivalently between naïve "fascination" and "nervous awareness" during the 1940s and 1950s.5 But The Eavesdroppers brought the national discussion to a fever pitch. In the 1960s, journalists and academics began citing the book as irrefutable evidence of mounting wiretap abuse. The U.S. Supreme Court distinguished the PBAE study in two of the period's most important Fourth Amendment decisions.6 And federal lawmakers entered portions of the finished text into the record of every major hearing on communications privacy that Congress held between 1959 and 1968, when legislative reforms appeared to render the book obsolete.7 By the end of the decade, commentators of all political stripes were frantically sounding the alarm of a full-blown "electronic listening invasion," mostly on the basis of Dash's findings.8 The march of technological progress finally appeared to have trampled the nation's bedrock values. No one seemed safe.

This article uses the publication of The Eavesdroppers to chart this momentous swing in popular perception during the late 1950s and early 1960s: from benign interest in wiretapping to anxiety over the collapse of the American right to privacy, from fascination with electronic eavesdropping technology to alarm over its seemingly limitless reach. In the process, I argue for a more historically grounded understanding of wiretapping and electronic eavesdropping than critical orthodoxy has seemed to allow. The 1950s and 1960s have long been remembered as a period of intensified government surveillance in the United States, and, as a result, scholars in a variety of fields have exerted a great deal of energy uncovering the clandestine eavesdropping programs that the federal government undertook at the height of the Cold War.9 No one can deny the truth of that narrative, or its relevance to the realities we now confront under the watchful eye of the NSA. But the importance of the "surveillance state"—that master metaphor of modern surveillance studies—to midcentury debates about wiretapping and electronic eavesdropping has been largely overstated.10 As we'll see, the activities of the U.S. government's eavesdropping apparatus in the postwar period were varied and contradictory, at times even incoherent. And prior to the watershed revelations of the Church Committee in the 1970s, Americans tended to regard a much broader range of phenomena as intrusions on communications privacy than we would perhaps recognize today. The eavesdropping threat loomed large during the 1950s and 1960s: in the work of state and local law enforcement agencies, who wiretapped extensively in criminal investigations; in the exploits of private investigators and eavesdropping specialists, who capitalized on technological innovations to expand their industry's reach; and, perhaps most importantly, in the contradictions of state and federal lawmakers, who sent conflicting messages about the legitimacy of eavesdropping practices that had dogged the nation's communications infrastructure for more than a century. Following the cultural career of The Eavesdroppers suggests that government entities like the FBI and the CIA were part of a much bigger story.

This article tells that story, recovering an "unofficial" history of eavesdropping during the 1950s and 1960s that scholarly focus on government surveillance has long obscured. My account is divided into two main parts. The first part outlines the core findings of Dash's 1959 study, which elicited varying responses in light of the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark decision in Benanti v. United States (1957) two years earlier. The result of a failed New York Police Department drug investigation, the Benanti case suggested that all official forms of law enforcement wiretapping fell under the jurisdiction of the 1934 Federal Communications Act. This meant that police agencies could no longer rely on recorded telephone conversations to gather evidence and convict suspects. As state and federal authorities scrambled to bring their wiretap procedures in line with the Benanti decision, The Eavesdroppers began to look less like a neutral investigative report and more like an opportunistic political attack. Well into the 1960s, the book continued to serve as a lightning rod for debates about the ability of a frighteningly wide range of third parties—not just the federal government—to listen in on ordinary American citizens.

The second part of this article examines the proliferation of concealed electronic eavesdropping devices, or "bugs," in exactly this same period, one of the PBAE investigation's most sensational discoveries. A crucial quirk of the Benanti ruling was that it appeared to outlaw wiretapping (eavesdropping via telephone) but not bugging (eavesdropping via microphone). Where one door closed, another opened: on the heels of the invention of the electronic transistor, which helped to miniaturize clandestine listening devices, the loopholes in the Benanti decision led to the explosive growth of the bugging business in the United States. As I demonstrate, the rise of the hidden microphone during this period is perhaps best captured in the popular visibility of two professional eavesdroppers who ended up cooperating extensively with Dash's investigation: mob wiretapper-turned-Christian evangelist Jim Vaus and San Francisco private eye Harold K. Lipset. The national response to their exploits also reveals just how powerfully nonstate actors shaped the public image of eavesdropping during the late 1950s and early 1960s, when miniature listening devices began to seem everywhere and nowhere at once.

* * *

Wiretapping is as old as wired communication. Civil War generals traveled with professional telegraph tappers in the 1860s, law enforcement agencies began planting telephone taps in the 1890s, and corporate communications giants tacitly sanctioned state and federal eavesdropping programs of various sorts for most of the twentieth century. Somewhat surprisingly, this wasn't a drama that played out in the shadows of American life. Police eavesdropping garnered front-page headlines during the 1920s, when the telephone tap emerged as an effective tool in the enforcement of Prohibition laws. The passage of the 1934 Federal Communications Act (FCA), which provided that "no person . . . shall intercept any communication and divulge or publish the existence, contents, purport, effect, or meaning of such intercepted communication to any person," sparked widespread debate over the legality and extent of third-party eavesdropping. And more than 75 articles about the practice of wiretapping—its uses, its limitations, and the technologies that made it possible—appeared in mainstream American magazines between 1934 and 1955 alone (10).

Yet in 1956, when the PBAE commissioned its nationwide investigation, fact was still difficult to separate from fiction. While most Americans shared a vague sense that wiretapping constituted a "national problem," no one seemed to know what the problem actually entailed. Dash used the confusion as the starting point for The Eavesdroppers. The book's three main parts, written separately by the three core members of the PBAE research team, were intended to offer an objective look at an issue ordinarily clouded by hearsay. In Part I, Dash outlined the history of wiretapping in the United States and presented the results of the investigation. He limited his report to nine jurisdictions that best represented the range of the study's findings: Baton Rouge, Boston, Chicago, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, New Orleans, New York City, Philadelphia, and San Francisco. In Part II, Richard Schwartz, the engineering expert in the group, explored the technical innovations behind wiretapping and electronic eavesdropping, from the tape recorder to the parabolic microphone. In Part III, Robert Knowlton surveyed relevant judicial decisions and legal statutes, dating back to the prohibitions against eavesdropping in Blackstone's Commentaries.

The mix of voices within the three sections gave the study the appearance of offering divergent opinions on the nature of the issue at hand. But Dash stressed that he was united with his co-authors in offering an impartial account, free of political biases and policy recommendations. Even so, the published product suggested something of Dash, Schwartz, and Knowlton's ideological leanings. Along with lurid promotional copy about the study's contents ("the unknown story of wiretapping today—its victims, its practitioners, the technologies, and what the law says about it"), the front jacket of the book featured the image of a keyhole-shaped silhouette, out of which peered the glowering red eye of a Peeping Tom. The metaphor was mixed, but it didn't obscure the underlying message: the mechanisms that guaranteed the American right to privacy, from locks to laws, no longer offered adequate protection.

For Dash, this was a major political reversal. Dash had made his name in the early 1950s as an outspoken defender of law enforcement wiretapping, and in 1955 he appeared before House Committee on the Judiciary to fight a proposal for more restrictive national wiretap policies. Drawing on his experience in the Philadelphia District Attorney's office, Dash also published an article in the Dickinson Law Review that same year arguing that that wiretapping wasn't "an unfair or coercive procedure," but rather an "'ear witness' of crime—almost, if not as good as, an eye witness."11 Critics in a variety of fields were already inveighing against this line of reasoning. But Dash pointed out that they usually made the case against law enforcement wiretapping either by enumerating scandalous local incidents of wiretap abuse, or by limiting their accounts of the problem to cities that were popularly regarded as wiretapping "hotbeds," such as Washington, D.C., and New York City. In less publicized jurisdictions, according to Dash, the benefits outweighed the costs, and nowhere was this more true than in Philadelphia, a midsize city with a rising rate of organized crime. As he told the House Committee on the Judiciary in 1955, "We would be powerless in Philadelphia today to combat organized crime and rackets if we could not wiretap. . . . Without wiretapping, Philadelphia's crime problem would be indeed a serious one."12

Writing The Eavesdroppers changed Dash's opinion. Instead of focusing on sensational incidents and wiretapping hotbeds, the PBAE investigation took what amounted to a bird's eye view, aggregating the experiences of multiple jurisdictions to reveal the scope of wiretap use on a national scale. The approach gave the authors of the study an opportunity to identify trends that had long eluded both sides of the eavesdropping debate. According to Dash, the source of the American "wiretapping crisis"—now identified as such—wasn't the vulnerability of the telephone system or the proliferation of unlicensed private surveillance experts (two of the most common explanations during the 1940s and 1950s), but the contradictions inherent in American eavesdropping policy. As he explained in the opening section of The Eavesdroppers, by far the most widely cited of the three, wiretapping was indeed illegal on the federal level. Despite the ambiguities of the "intercept and divulge" rule, the U.S. Supreme Court had plainly affirmed the anti-wiretapping implications of the Federal Communications Act in two major rulings in the late 1930s.13 Yet as Dash discovered, government agencies were finding creative ways to circumvent the federal wiretap ban, and wiretapping policies at the state level remained chaotic and unenforceable. While "permissive" states like Louisiana and Massachusetts upheld relatively lax wiretapping laws, "prohibition" states like Illinois and California barred wiretapping outright. (California's wiretap restrictions were the nation's oldest, dating back to the 1860s.) While some states had well-established systems for regulating the use of wiretaps by law enforcement agencies and private citizens, a disconcerting number still remained "virgin jurisdictions," with no wiretapping laws on the books. As Dash pointed out, the "confused and mixed up situation" between states and the federal government created some confounding legal paradoxes.14 Although federal officials could be sentenced to prison for wiretapping, state officials could wiretap with impunity, even when openly committing a federal crime in doing so. And regardless of what state and federal statutes said (or didn't say) about the use of wiretap evidence in court, law enforcement agencies could still use wiretap leads to pursue police investigations and arrest criminal suspects. Licensed private detectives, many of whom specialized in electronic eavesdropping and tapped for hire in insurance investigations and divorce cases, occupied the same legal no-mans land.

The thicket of legal contradictions made it impossible to prevent wiretap abuse. As Dash discovered, the federal government rarely enforced its wiretapping ban. The crime was exceedingly hard to detect—only one individual had been brought to federal trial for wiretapping since the passage of the FCA in 1934.15 State prosecutions turned out to have been just as rare, and the upshot was that police officials and private investigators were able to eavesdrop indiscriminately, regardless of whether they did the dirty business of wiretapping in "permissive," "prohibition," or "virgin" jurisdictions. In Boston and New Orleans, two of the most laissez-faire districts in the country, Dash discovered that police tapped extensively in criminal investigations, but seldom reported doing so in official documents. They also avoided using wiretap evidence in criminal trials. The code of silence was part of a gentleman's agreement with local telephone companies, who had a vital interest in preserving the public fiction of secure telecommunications (122-123). In New York City, where wiretapping was regulated by a strict court-order system, plainclothes police officers were planting as many as 100 illegal taps a day, a number well in excess of official estimates (68-69). District attorneys were also hiding microphones in police interrogation rooms to gather information about criminal suspects (77).

Similar problems of oversight plagued law enforcement agencies in Chicago and Los Angeles, two cities where wiretapping was prohibited. Despite the best efforts of the Illinois State's Attorney's office to discourage illegal eavesdropping, the Chicago Police Department maintained an intelligence unit of more than 40 officers whose sole duty was to tap wires (217). And in Los Angeles, Dash revealed that police agencies were routinely skirting California's stringent eavesdropping laws by hiring freelance wiretapping experts—"private ears," as they were then known—to assist with criminal investigations (164-165). The collusion between the two sides was an open secret. Dash was amused to discover that more than 60 private detectives in the Los Angeles area openly advertised illegal wiretapping services in the city's yellow pages (208-209). Accompanying many of these entries were racy promotional illustrations that featured men with headphones listening to the telephone conversations of unwitting female callers.

The ineffectiveness of the nation's eavesdropping laws opened other avenues for wiretap abuse, as well. The fact that electronic surveillance experts operated in "a carefree manner . . . unafraid of law-enforcement interference" was well-known by the time the PBAE commissioned its study, particularly since the telephone tap had emerged as an effective weapon in marital infidelity cases during the 1940s and 1950s (82). Yet Dash also suggested that one of the newest, and most lucrative, fields for the professional eavesdropper was corporate espionage. A Harvard Business School study reached the same conclusion in 1959: a growing number of American companies were hiring wiretapping specialists to spy on employees and competitors alike.16 Under the condition of anonymity, business executives around the country told Dash that they frequently tapped office telephones if they suspected their workers of stealing, or if they feared the influence of unions among their ranks (95). Some admitted to planting recording devices in office restrooms. In an ironic twist, Dash found that telephone companies weren't averse to tapping their own lines for this same purpose (96). Some of the nation's most skilled wiretappers turned out to have been telephone company linemen, who were illegally hiring out their services to law enforcement agencies and private investigators, thereby completing the sinister circle (316).

The abuses were shocking, and readers weren't lost on the fact that the individual sections of The Eavedsroppers told a coherent story about the steady erosion of time-honored American values. One reviewer wrote that Dash, Schwartz, and Knowlton's research depicted a "thoroughly unpleasant society."17 Another lamented that "only America . . . could produce a book of this sort."18 The details about carefree private ears and prying business executives weren't what led readers of The Eavesdroppers to make such sweeping pronouncements, however. Above all else, it was the book's portrayal of the police. "There is something disturbing . . . about the position that law enforcement officers should be permitted to violate the very law they are sworn to uphold. That is hypocrisy," wrote a reviewer in the American Bar Association Journal.19 To be sure, the idea of the police tapping the wires in open defiance of state and federal laws gave many the impression that the nation was careening inexorably toward totalitarianism. According to an article on The Eavesdroppers in Commentary, "When police install taps or bugs, they are in effect laying traps, and taking over some of the functions of a secret, or political, police. When they go so far as to . . . bug a conversation between a suspect and his lawyer in a prison cell or when they have to rely on eavesdropping informers, as is generally necessary in tapping cases, the health of the society is obviously jeopardized. It is the old question of power and corruption."20 Missouri Senator Thomas C. Hennings, Jr., Chair of the Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights during the 1950s, likewise called The Eavesdroppers an "appalling" read based on the book's allegations of clandestine police wiretapping.21

And yet, as damning as the PBAE's findings seem in hindsight, the public response to The Eavesdroppers was far from uniform. The book inspired as much support for wiretapping as outraged opposition, and the argument in defense of the practice similarly hinged on the charges that Dash had leveled against American law enforcement. To understand why the excesses detailed in The Eavesdroppers would have stood justification in the late 1950s and early 1960s—indeed, to understand why the PBAE investigation provoked debate at all—it's necessary to take a detour through curious wiretapping case in New York City. It involved two brothers, Salvatore and Angelo Benanti, who were convicted of a crime they weren't suspected of committing. Their case played an important role in stoking the fires of the controversy that ensued.

* * *

During the early 1950s, Salvatore and Angelo Benanti ran a small but lucrative drug organization out of the Reno Bar, a notorious mafia haunt on Manhattan's lower east side.22 In March 1956, hoping to mount a viable state narcotics case against the Benantis, a New York judge granted an official New York Police Department (NYPD) request to tap the Reno's telephones. For a long month and a half that spring, the NYPD picked up little in the way of useful information. But on the afternoon of May 10, 1956, officers overheard Salvatore make an urgent call to an unknown recipient about the delivery of "eleven pieces" later that evening. A major bust seemed imminent. Around 7:00 PM, officers saw Angelo leave the Reno and drive off in a light-green Chevrolet coupe. They followed his car for several blocks and pulled him over.

When the investigating officers searched Angelo's vehicle, they had little trouble finding the "eleven pieces" that Salvatore had mentioned on the phone. The problem was that "pieces" in question were eleven five-gallon containers of alcohol—contraband that had nothing to do with the trafficking of narcotics. With the prospect of a blown wiretap at hand, the officers arrested Angelo on the grounds that the containers in the car lacked the tax stamps required by federal law. This was a relatively minor charge, an awkward throwback to the bootlegging wiretaps of the Prohibition era. But the untaxed alcohol at least gave the NYPD the power to turn over the Benantis to federal authorities and proceed with an indictment.

What started as a state narcotics investigation had accidentally turned federal, and the turn of events put the prosecution in an uncomfortable position. The state of New York had an extensive court-order system in place for authorizing law enforcement wiretaps. Established in 1938, it was the nation's first. This meant that the incriminating information about Salvatore—the "eleven pieces" conversation—was legal to use as evidence in a New York state court. But the case against the Benantis was no longer under New York jurisdiction. On the federal level, per Section 605 of the FCA, the interception and divulgence of telephonic communications was illegal. If federal prosecutors revealed the source of the information that had led to Angelo's arrest and tied the crime to Salvatore, the entire case against the Benantis would be jeopardized.

When Salvatore Benanti went to trial in August 1956, the prosecution's initial strategy was to keep the existence of the Reno Bar wiretap under wraps. (Angelo pled guilty in exchange for reduced jail time soon after his arrest.) But Salvatore's attorney, George Todaro, sensed that something was amiss as soon as the investigating officers were called to testify. What else but a wiretap could explain why the NYPD had arrested the Benanti brothers, suspected drug dealers, for an offense as inconsequential as the transportation of untaxed alcohol? Shouldn't the case against Salvatore be dismissed since it relied on "fruit of the poisonous tree" (illegally obtained evidence)?

The presiding judge didn't think so. The federal officers who handled the Benanti investigation had nothing to do with the Reno Bar wiretap, which was itself sanctioned by a court order. Accordingly, on October 9, 1956, Salvatore Benanti was convicted and sentenced to 18 months in prison. Todaro subsequently challenged the decision. As he summarized the argument against his client's conviction, "Despite the warrant issued by the New York State court pursuant to a New York law, we have no alternative other than to hold that in tapping the wires, intercepting the communication made by the appellant [Salvatore Benanti] and divulging at the trial what they had overheard, the New York police officers violated the federal statute."23 A Second Circuit judge affirmed the conviction in May 1957, spurring another round of appeals. The U.S. Supreme Court agreed to hear the case late that same year.

What happened next surprised many. On December 9, 1957, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the NYPD officers who originally pursued the Benanti investigation had in fact violated the Federal Communications Act, despite the presence of a wiretap order signed by a New York state judge. Salvatore Benanti's conviction was overturned. The language of the opinion answered any questions as to whether the ruling was meant to clarify the longstanding uncertainty surrounding the FCA's relationship to state wiretap law. Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Earl Warren explained that the "plain words of the statute created a prohibition against any persons violating the integrity of a system of telephonic communication and . . . evidence obtained in violation of this prohibition may not be used to secure a federal conviction." The FCA was thus an "express, absolute prohibition against the divulgence of wiretapping," and the court-ordered tap on the Reno Bar was merely "another example of the use of wiretapping that was so clearly condemned under other circumstances."24 The implication of the Court's reasoning was momentous: it was a federal crime to tap a wire and divulge its contents, regardless of what the states had to say about the matter. After two decades of turning a blind eye to the conflict between state and federal wiretapping laws, the U.S. Supreme Court had finally moved to bring order to statutory chaos.

As legal experts were quick to point out, a second ruling handed down later that same week—Rathburn v. United States (1957)—partially mitigated the Court's anti-wiretapping stance, and the language of the Benanti opinion did little to encourage federal authorities to begin prosecuting state law enforcement officials for violating the FCA.25 Nevertheless, the decision had dramatic short-term consequences. Within weeks, New York state courts were forced to postpone several cases involving warranted wiretaps, and three other states with court-order systems—Maryland, Oregon, and Louisiana—began to reevaluate the legality of their policies.26 New York State Supreme Court Justice Samuel H. Hofstadter even went so far as to stop signing wiretap requests in light of the Benanti ruling. In an extended memorandum on the subject, Hofstadter declared that "when state officers indulge in wiretapping they are violating Federal law and subject themselves to Federal prosecution." According to Hofstadter, Benanti implied that the stain of illegitimacy went all the way up the chain, from the police officers who tapped the wires to the judges who signed the wiretap requests. "Clearly a judge may not lawfully set the wheels in motion toward the illegality by signing [a wiretap] order," Hofstadter concluded. "[T]he warrant itself partakes of the breach, willful or inadvertent, of the Federal law."27 A New York Times columnist underscored the same point in the weeks following the decision: "[A]ny state official who stands up and offers wiretap evidence at a trial will now be proclaiming the commission of a Federal crime, with whatever moral sanctions that implies."28

Legal historians tend to discount the importance of Benanti v. United States, narrating the story of American wiretap law as though little of significance transpired between the Supreme Court's notorious ruling in Olmstead v. United States (1928) and its major eavesdropping decisions of the late 1960s, which provide the precedent for the system of law enforcement wiretapping under which we live today.29 When the Benanti ruling is remembered, if at all, it's typically as a small but necessary step toward the abolition of the so-called "silver platter" doctrine, which gave federal authorities the freedom to use evidence seized illegally by state police.30 But viewing Benanti solely from the perspective of legal history obscures its cultural import. In its day, the ruling was a political bombshell, provoking backlash among liberals and conservatives alike.

On January 17, 1958, a month and a half after the Court's decision, six members of the U.S. Senate Rackets Committee proposed a bill exempting state law enforcement officials from the scope of the Benanti ruling.31 (Coincidentally, one of the two members of the committee who refused to sign off on the bill was a charismatic young Senator from Massachusetts whose Presidential administration would later become the target of a congressional eavesdropping inquiry.) The exemption had little hope of passing in Congress. Instead, the proposal was part of a broader political campaign designed to convince the American public that Benanti represented a dangerous blow to law enforcement. The idea was timeworn. Attempts to portray restrictions on eavesdropping as harmful to public safety are almost as old as eavesdropping itself. But the wiretapping-as-necessary-evil argument became something of a noisy refrain in the months following the Benanti decision, and nowhere more so than in the state of New York, where the ruling appeared to have the most impact.

In December 1957, the Executive Committee of the New York State District Attorney's Association drafted an official resolution asserting that Benanti "deprives State prosecutors and other law enforcement officers of one of the most effective weapons in combating serious crimes and organized criminal activity."32 One month later, the more liberal-minded staff at the New York Times ran an official editorial statement condemning the Supreme Court's move to curb state law enforcement wiretapping. According to the Times, although "no one who believes in the individual's right of privacy likes the idea of law-enforcement officers . . . secretly listening in on telephone conversations," the Benanti decision had robbed police agencies of a "necessary weapon" in the fight against crime.33 Edward S. Silver, an outspoken District Attorney for King's County, New York, cast the ruling in a much darker light: "If, for any reason, the Senate or the Congress doesn't do something to correct the Benanti decision, we just will not be able to use wiretapping in our law enforcement, and it simply means that a lot of people are going to have carte blanche in their criminal operations. You will not be depriving me but the people who elected me to fight crime in our county. If I am compelled to hunt lions with a peashooter, so be it."34 By 1960, Silver was already claiming that Benanti had "seriously crippled law enforcement."35

Benanti v. United States would receive little more than passing mention in the text of The Eavesdroppers, a curious fact to consider given that Dash, Schwartz, and Knowlton were still in the initial phases of their research when the Supreme Court handed down the ruling. In the book's final section, Knowlton briefly remarked that the decision had the potential to bring about a "long overdue appraisal of the relationship between the federal and state laws" (423). But the book's authors seemed reluctant to wade their way into an ongoing controversy beyond that. Dash, for his part, ended up taking a much more measured stance on the ruling than his colleagues in New York. In 1959, he went on record as supporting Benanti as an important step in reconciling the contradictions between state and federal wiretapping laws. But he also predicted that the new judicial precedent was unlikely to have any lasting effects on the ground because the Supreme Court had stopped short of formulating its opinion in Benanti as a rule of evidence. As Dash pointed out, this small but significant loophole left the door open for state officials to divulge wiretap leads in criminal trials: "[E]ven though the Benanti decision may make wiretapping illegal in a State . . . if that State has a rule of evidence admitting illegally seized evidence in court, then wiretapping, though illegal, may still be the basis for a prosecution. . . . A police officer does commit a crime, a Federal crime, by wiretapping, but that evidence in certain states throughout the country may still be used."36 Notwithstanding the temporary stays on court-ordered wiretaps in New York, state law enforcement agencies could, in this interpretation of the ruling, proceed with business as usual. Benanti thus seemed likely to go the way of prior Supreme Court wiretapping decisions, which were neutralized by loopholes soon after they were handed down. The doomsday scenario of organized crime running amok was overblown.

As it turned out, Benanti v. United States influenced the practice of police eavesdropping in an altogether different way—an issue we'll consider later on. For the time being, what's crucial to highlight here is how rapidly the Supreme Court's 1957 decision fanned the flames of an ongoing debate over the place of wiretapping in American law enforcement. Dash quickly found his research caught in the middle. Despite his attempt to minimize Benanti's relevance to the abuses that The Eavesdroppers uncovered, the new precedent ended up casting a long shadow on the PBAE study's public reception. In the wake of the Supreme Court's most controversial wiretap ruling in decades—a ruling that to many seemed to hamper the police's ability to combat sophisticated criminal organizations and national security threats—The Eavesdroppers came to look like something other than an neutral fact-finding investigation. While a handful of reviewers lauded the book as a crucial first step in clarifying the chaotic field of American wiretap policy, a far more vocal contingent yoked the book to the Benanti decision, denouncing The Eavesdroppers as the latest in a series of unwarranted attacks on American law enforcement.

The attempt to discredit The Eavesdroppers along these lines in fact began before the book appeared in print. Consider, for instance, Edward S. Silver's comparison of fighting organized crime after Benanti to "hunting lions with a peashooter," mentioned above. The analogy was part of Silver's July 1959 testimony before the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights, and it came as a sudden digression in a much longer screed against Dash, who had testified earlier that same day. Silver wanted to cast "very serious doubt" on Dash's portrayal of law enforcement wiretapping, and his criticisms implied that The Eavesdroppers, which was slated for publication two months later, ran the risk of stoking "fanciful and imaginary fears . . . of what is going to happen in our country if we permit a lawful wiretap."37 In Silver's opinion, both Dash and the U.S. Supreme Court had wrongly collapsed the "distinction between law enforcement agencies who are fighting crime and private groups or persons who use wire tapping for nefarious purposes," thereby criminalizing a form of police work that had become increasingly necessary in the electronic age.38 To solve this problem, Silver somewhat improbably proposed a moratorium on the use of the terms "wiretapping" and "eavesdropping" in public discourse about police surveillance. Both words seemed to have unfairly sinister connotations.39 In titling The Eavesdroppers as he did, Dash appeared to be playing to popular misconceptions about the police's ability to listen in on the conversations of American citizens. In Silver's view, he was kicking the nation's law enforcement agencies when they were already down.

Frank S. Hogan, a Manhattan District Attorney, shared many of Silver's sentiments. Hogan was particularly stung by The Eavesdroppers. He had offered to help Dash in the early stages of the PBAE investigation, only to find the policies of his jurisdiction slammed in the pages of the book. "Several members of the National District Attorneys' Association cooperated with one of the authors of this book because they understood the purpose of the book was to make an objective study of 'wire tapping,'" Hogan complained. "But it seems quite apparent from the moment one reads the title, looks at the jacket of the book (with a huge eye looking through a keyhole), and checks some of the footnotes and authorities which are used to substantiate the 'facts' of the book, that the authors became more interested in writing a best seller than conducting an objective research." Hogan continued: "It is unfortunate . . . that much of this discussion has been dominated by emotional considerations and fed by a wealth of irresponsible and inflammatory 'data.' Such recklessness, from purportedly objective sources, has served to harm rather than secure the interests of the public. . . . The authors of The Eavesdroppers have firmly aligned themselves with this damaging contingent of critics by painting, particularly concerning New York City, a picture bearing no factual resemblance of the true situation, as known by reputable officials. They grind their axe upon a wheel of untruth and far-fetched speculation."40 For Hogan, The Eavesdroppers and the Benanti ruling were allied forces: both defended civil liberties at the expense of civic safety. The language he used to discredit Dash's study came directly out of the growing criticism of the Supreme Court—to be sure, the "damaging contingent of critics" who were hurting the cause of law enforcement in New York could have just as easily referred to the nine justices who unanimously voted to overturn Salvatore Benanti's conviction.

Squabbles over the content of The Eavesdroppers continued into the early 1960s. A sharp divide emerged in the commentary on the significance of the book's findings, indicative of a growing schism between "anti-" and "pro-" wiretapping camps in the national debate over eavesdropping reform. When the criminal procedure scholar Yale Kamisar convened a special issue on the "Wiretapping-Eavesdropping Problem" for the Minnesota Law Review in the winter of 1959-1960, he could only imagine Dash, Schwartz, and Knowlton's research as the starting point for the discussion.41 Kamisar sensed that The Eavesdroppers had caused "not inconsiderable controversy." For the foreseeable future, the issue of wiretap abuse among law enforcement officials and private citizens would have to be "approached in defense or attack of the work of these men [Dash, Schwartz, and Knowlton]."42

The issue of the Minnesota Law Review on The Eavesdroppers eventually appeared in April 1960. In the interest of political balance, it featured "pro-wiretapping" contributions from Edward S. Silver and the private investigator Harold Lipset, both of whom defended the right to eavesdrop using the latest electronic technologies. The representatives of the "anti-wiretapping" camp were Thomas C. Hennings, Chair of the Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights; Edward Bennett Williams, Chair of the American Bar Association's Committee on Criminal Defense Procedures; and Yale Kamisar himself. Clear rhetorical patterns emerged on both sides of the debate. Criticism of the book gave way to condemnation of Benanti v. United States and support for law enforcement tapping. Silver, for instance, began his contribution to the symposium by blasting Dash's study ("an innuendo-splattered thriller"), and concluded with a gloss on the necessity of violating privacy in special cases to protect the public interest.43 By contrast, defenses of The Eavesdroppers were tantamount to arguing for a ban on eavesdropping in all of its forms. The three articles that unequivocally praised the book all closed with strident calls for a legislative crackdown.

By the early 1960s, then, The Eavesdroppers had emerged as a bellwether for the course of wiretap reform in the United States. Whatever else Dash, Schwartz, and Knowlton's research revealed about the scope of the "wiretapping-eavesdropping problem," the book laid bare an unbridgeable divide in the public debate on the issue, projecting two different courses for the nation to take in the coming decade. There were those who believed that wiretapping should be permitted in special cases, particularly cases involving organized criminal activities and national security threats. And there were those who believed that wiretapping should be banned altogether. While few made the argument that the field should remain unregulated, the two camps shared little common ground. A legislative stalemate seemed likely. When federal lawmakers brought four different wiretap reform bills to Congress early in the spring of 1961, none went forward.44

State legislatures around the country had better luck at reaching consensus, but the new policies they crafted merely served to reinforce the same general schism.45 On one end of the spectrum were the states that elected to capitalize on apparent loopholes in the Benanti ruling. Between 1957 and 1959, Maryland, Massachusetts, Nevada, and Oregon passed laws permitting the use of wiretap evidence in state courts, indirectly sanctioning state police wiretapping despite its newly firm status as a federal crime. On the other end of the spectrum were the states that followed the Supreme Court's cue in Benanti. California, Florida, Indiana, Illinois, and New Jersey all either passed new laws banning wiretapping at the end of the 1950s, or made moves to shore up old statutes that had the same effect. Pennsylvania—Dash's home state, the source of the PBAE investigation—ended up taking the latter approach.

At the dawn of the new decade, the running tally of state wiretapping laws reflected the difficulty the nation would face in bringing its contradictory eavesdropping policies into alignment. Six states had statutes authorizing law enforcement officers to tap under various circumstances, while 33 states prohibited wiretapping outright. 11 states still had nothing on the books.46 Despite the apparent impasse, the privacy law expert Alan Westin believed there was new cause for optimism. The Eavesdroppers had exposed too much to let the issue recede once again into the background of public consciousness. "Whichever approach emerges from the current debate as the dominant public reaction, the most satisfying aspect of the wire tapping revolt . . . is the proof that Americans value their constitutional privacy too highly to let it ebb away before an advancing technology or the forays of official and unofficial intruders," Westin remarked in "Wiretapping: The Quiet Revolution" (1960), a tellingly titled essay for Commentary. "This is a promising start to what must be the next step—a full-scale federal clean-up in the 1960s and extension of state control laws to fifty jurisdictions. When this is accomplished, the tools for protecting privacy in the electronic era will be at hand."47

Westin had a few more years to wait for that next step, perhaps longer than he might have expected given the newfound urgency of the national debate. A more unsettling problem was on the horizon, a problem at once both big and small. True to form, Dash, Schwartz, and Knowlton were among the first to see it looming in the distance.

* * *

Eavesdropping technologies of various sorts have been around for centuries. Prior to the invention of recorded sound, the vast majority of listening devices were extensions of the built environment. Perhaps nodding to the origins of the practice (listening under the eaves of someone else's home, where rain drops from the roof to the ground), early modern architects designed buildings with structural features that amplified private speech. The Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher (1601-1680) devised cone-shaped ventilation ducts for palaces and courts that allowed eavesdroppers to listen to other people's conversations. Catherine de' Medici (1519-1589) is said to have installed similar structures in the Louvre to keep tabs on individuals who might have plotted against her. Architectural listening systems weren't always a product of intentional design. Domes in St. Paul's Cathedral in London and the U.S. Capitol building still serve as inadvertent "whispering galleries," enabling prying ears to hear conversations held on the other side of the room. Archaeologists have discovered acoustical arrangements like these dating back to 3000 B.C.E. Many were used for eavesdropping.48

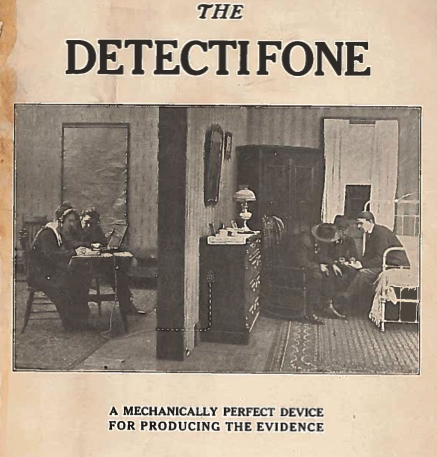

The earliest electronic eavesdropping technologies functioned much like architectural listening systems. When installed in fixed locations—under floorboards and rugs, on walls and windows, inside desks and bookcases—early-twentieth-century devices like the Detectifone, a technological cousin to the more common Dictaphone, proved surprisingly effective (see Figure 1). According to a pamphlet published in 1917, the Detectifone was "a super-sensitive device for collecting sound in any given place and transmitting it by a wire thru [sic] any given distance to the receiving end, at which point the person or persons listening are able to hear all that is said at the other end. . . . The result is the same as though you were present in the room where the conversation was being carried on."49 Such devices were typically marketed to the police as investigative tools. But manufacturers also envisioned a wide range of alternative uses: verifying the loyalty of business associates, corroborating statements made under oath, even monitoring patients in hospitals and insane asylums.50

The devices that we now think of as "bugs" emerged much later. During the late 1940s, electronic innovations made it possible for eavesdroppers to miniaturize listening technologies like the Detectifone. This made them easier to hide. It also freed them from the strictures of the built environment, dramatically expanding their reach. Reports of an American bugging epidemic began circulating in the early 1950s—first, as glimpses of the man-made miracle of electronics miniaturization began to appear in national newspapers, popular magazines, and Hollywood films, and later as congressional subcommittees revealed scandalous tools of the eavesdropping trade on the floor of the United States Senate. The numbers were impossible to substantiate, but by 1960 all accounts suggested the bug had noticeably outstripped the wiretap as the professional eavesdropper's weapon of choice. "Whereas so much attention has been put to wiretapping," Dash explained in 1959, "the widest use of eavesdropping by private people and law enforcement today is through the use of microphones."51 The electronic listening invasion had begun.

The middle section of The Eavesdroppers, written by the University of Pennsylvania engineer Richard Schwartz, was intended to account for this new development. Brusquely titled "Eavesdropping: The Tools," Schwartz's chapter took stock of the listening devices that professionals were using in the field. In the process, Schwartz told a more disconcerting story about ordinary technologies turned against the society that had created them. There were induction coils that allowed eavesdroppers to listen to telephone conversations without making physical contact with telephone wires (318-323). A special brand of conductive paint, invisible to the unaided eye, could redirect phone signals to outside lines (316-317). There was a new class of microphones engineered to be smaller than sugar cubes and thinner than postage stamps. These could be secreted away in surprising locations, transforming everyday items into covert listening machines: wall sockets, picture frames, packs of cigarettes (339-343). Then there were the technologies of remote listening, futuristic gadgets that seemed to defy the laws of physics. Tiny radio transmitters embedded in briefcases or wristwatches could broadcast conversations to eavesdroppers lying in wait elsewhere (343-346). Directional microphones shaped like satellite dishes and shotguns could intercept conversations from thousands of yards away (346-353). Schwartz even reported on the development of an eavesdropping laser beam, long rumored to have been on the open market (353-358). Unfortunately—or fortunately, depending on how you looked at the situation—this was the only device that he discovered to be apocryphal.

There were two main reasons why electronic listening devices were on the rise during the late 1950s and early 1960s. The first was that bugging still represented something of an uncharted legal frontier in this period. Although devices like the Detectifone had been available to police and private citizens since the early 1900s, it wasn't until the early 1940s that the U.S. Supreme Court had the chance to consider their constitutionality. In Goldman v. United States (1942), FBI agents had attached a warrantless "detectaphone" (the spelling referred to a general eavesdropping device, not necessarily one made by the Detectifone brand) to a wall adjoining the office of an attorney suspected of fraud, using what they overheard to secure his conviction.52 The Court upheld the verdict on the grounds that the government's use of a listening device wasn't a violation of the Fourth Amendment: the detectaphone hadn't physically trespassed onto Goldman's property, and the criminal evidence that the FBI "seized" through its use—oral speech—wasn't materially tangible. The ruling appeared to signal that the manufacture and use of concealed listening devices could continue unabated. The Court's subsequent decisions in On Lee v. United States (1952) and Irvine v. California (1954), similar cases involving concealed microphones, didn't help matters.53 In 1959, Dash could still assert that electronic eavesdropping remained an "almost untouched area" in state and federal statutes.54 Edward Bennett Williams agreed at the start of the 1960s that bugging laws were "even more chaotic and outdated" than wiretapping laws.55

The years following the publication of The Eavesdroppers, which Dash later remembered as a "period of heightened awareness" of electronic listening devices, only seemed to muddy the waters.56 In Silverman v. United States (1961), the Supreme Court was presented with a case not unlike Goldman: without a warrant, FBI investigators had inserted a microphone attached to a long metal rod—a "spike mike"—into the baseboards of a suspect's home, using its acoustical properties to transform the residence's ductwork into a massive amplifying system. What the FBI heard through the ducts enabled federal prosecutors to convict Silverman. This time, however, the Supreme Court unanimously decided to overturn the verdict: the spike mike, as a physical extension of the investigating officers, had trespassed onto Silverman's private property, making the oral evidence against him (now distinguished as a "tangible thing") illegally obtained.

This was a clear victory for the Fourth Amendment—and a victory for The Eavesdroppers, which was directly cited in the Court's opinion.57 But the Silverman ruling balked on the more pressing question of what to do about the proliferation of electronic listening devices. According to Justice Potter Stewart, who wrote for the Court, the details of the Silverman case didn't require legal consideration of the "frightening paraphernalia which the vaunted marvels of an electronic age may visit upon human society," much less the FBI's use of the spike mike.58 All that mattered was that the investigating officers had physically intruded on Silverman's property. Bugging thus remained an open field. And for police and private investigators whose eavesdropping work had been hindered by the Benanti decision four years earlier, the road was clearer than ever. The safest course of action—that is, the least illegal—was to replace wiretaps with bugs.59 As the years wore on, supply followed demand.

And yet, as with this history of wiretapping in this period, the law only tells part of the story. The Supreme Court's earliest rulings on electronic eavesdropping—Goldman, Irvine, and Silverman—coincided with a flurry of technical innovations in the electronics industry. The ambiguity of the law made state and federal officials even less equipped to keep pace with the developments that ensued. This was the second reason for the bugging epidemic of the 1950s and 1960s: electronic eavesdropping technology had suddenly raced ahead, eluding the law's grasp and leaving eavesdroppers to operate without fear of reprisal. According to the professional eavesdropper Bernard Spindel, the "modern world of gadgetry" had created bugging techniques that "def[ied] the imagination and also detection." The rate of innovation in the field could already, in 1955, be compared to "the rapidity in changes of ladies' fashions," which all but ensured that regulatory efforts would lag behind the times.60 State and federal authorities agreed that there was little the government could do to stem the tide. "We've had some complaints about bugging, but we've never been able to catch anyone at it," Curtis B. Plummer, Chief of the Fedxeral Communication Commission's Bureau of Safety, admitted to the Washington Post in 1962. "We have reason to believe that most of the people who do this kind of work are thumbing their noses at us. . . . They just go ahead, knowing there's a small chance of getting caught."61 (In hindsight, Plummer's remarks have a ring of prophesy to them: the Federal Communications Commission passed a resolution prohibiting the use of bugging equipment four years later, only to discover that the ban had no effect.)62 Reports in venues as diverse as Time, Life, Business Week, the Chicago Tribune, and Popular Mechanics came to the same conclusion.63 Bugging techniques had become too effective to regulate through ordinary channels.

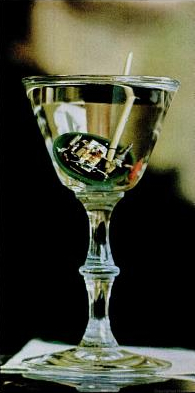

Behind the rapid advances in electronic eavesdropping was a single technological innovation: the transistor. Developed by researchers at Bell Laboratories in the late 1940s, transistors provided the means to make electronic components smaller, enabling the development of a host of devices that helped to reshape postwar American society: the calculator, the portable radio, the hearing aid, and (perhaps most importantly) the integrated circuit and the personal computer. Scholars typically identify the transistor as the breakthrough behind the birth of the information age.64 But there was an ominous side to the technology, often overlooked in historical accounts of its social application. Transistors were easy to construct, and, by the late 1950s, cheap and easy to acquire. When audio engineers and surveillance experts realized their potential, it ushered in what Harold Lipset later remembered as a period of "extreme miniaturization" in the field (see Figure 2).65 In The Eavesdroppers, Schwartz reported that "transistorizing" a bug halved its size without changing its overall manufacturing cost (344). The results, at times no bigger than the head of a matchstick, seemed nothing short of miraculous: bugged television sets, staplers, doorbells, and flower arrangements; bugged shirt buttons, tie clips, hat bands, and lighters; even bugged lipstick tubes and cavity fillings.66 As Alan Westin warned, these weren't "'Buck Rogers' developments, technically possible but still on the drawing boards." They were "already in use, and spreading across the nation with cancerous speed."67

All told, the combination of rapid technological innovation and crawling legal control yielded a situation that one federal official described as "total anarchy."68 Following Dash and Schwartz's lead, lawmakers gradually turned their attention to the bugging epidemic in the 1960s. The congressional hearings that ensued, led by Missouri Senator Edward V. Long and the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, mostly served to expand on the territory that The Eavesdroppers had already covered.69 But new details about the pervasiveness of electronic eavesdropping technologies began to emerge, at first in pieces, and then seemingly all at once. The U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations disclosed that a listening device had been lodged inside the state seal of the American Embassy in Moscow for the better part of a decade. Reports suggested that as many as one out of three divorce cases in major American cities involved a conversation intercepted by a hidden microphone, and as many as one out of five businesses had purchased top-of-the-line audio surveillance equipment to spy on competitors.70 A torrent of books and articles on the eavesdropping crisis appeared, some written by former professionals in the field. The titles suggested that the nation had at long last reached a point of no return: "Bug Thy Neighbor" (1964), The Privacy Invaders (1964), The Naked Society (1964), "The Big Snoop" (1966), The Intruders (1966), The Electronic Invasion (1967), The Ominous Ear (1968), The Third Listener (1969).71 And in the midst of the mounting anxiety, a private detective with a flair for the dramatic appeared before Congress and pretended to sip a dirty martini throughout the proceedings. The olive in the glass contained a listening device, designed to record conversations at a range of up to 40 feet. At the end of his testimony, he played back his opening statement for rhetorical effect.72

* * *

Much of the information about bugging detailed in The Eavesdroppers came from two sources who perhaps knew more than anyone else about the subject. One was J. Arthur Vaus, a reformed mob eavesdropper whose improbable conversion to Billy Graham's ministry captured the nation's attention in the 1950s. The other was Harold Lipset, a private investigator whose inventive use of electronic listening equipment made him a household name in the 1960s. (It was Lipset who performed the "bug in the martini olive" trick on the floor of the U.S. Senate in February 1965.) The two men followed similar paths to national notoriety. Both perfected the tools of their trade in the Army during World War II. Both began their careers doing freelance investigative work. And both ended up in the public eye during periods of heightened concern over threats to communications privacy. Yet despite their similarities, Vaus and Lipset also seem to embody two different registers of the eavesdropping debate at midcentury. During the 1950s, Vaus's bugging exploits were generally regarded as miraculous feats of human ingenuity, wonders of the electronic age. By contrast, when Lipset took center stage in the mid-1960s, Americans tended to view electronic eavesdropping in a more dystopian light, and his technological achievements accordingly seemed to portend the demise of the right to privacy. Taken together, their careers help illustrate the shift from wonder to alarm in popular discourse about eavesdropping, and highlight the importance of nonstate actors in the public history of electronic surveillance during this period.

J. Arthur Vaus, also known as "Big Jim" Vaus, grew up in Los Angeles, the son of a Baptist minister.73 He exhibited an interest in electronics early on, engineering his first listening device in an attempt to play an elaborate prank on his sister. When Vaus enlisted to serve in the military during World War II, his skills made him an ideal candidate for the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Despite an auspicious start in the Signal Corps' radar division, Vaus was eventually caught stealing military equipment and sentenced to ten years in an Army prison. An early release at the end of the war allowed him to return home and open a small electronics repair shop in Hollywood.

Business at the shop proved slow. But Vaus soon found more remunerative work when the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) approached him to assist on criminal cases. As Vaus explained the arrangement, "to see and not be seen was a constant problem of the police," and his homespun line of bugging equipment, manufactured in the back of his Hollywood shop, provided a convenient investigative solution (see Figure 3).74 "We had one gadget that made it possible for us to listen in to telephone conversations so that we didn't need to go anywhere near the telephone in question," Vaus recalled, looking back on the devices he built for the LAPD in this period.

We could sit back, on the other side of town, and hear all that was being said on that telephone—not only hear what was being said, but determine what telephone number was being dialed, without being near the phone and without any physical connection. We had another gadget that made it possible to take sound out of a room, through solid walls. From a listening post several miles away we could hear all that was being said. . . . We had what we called a 'talking cane,' where we couldn't get inside by any other means or method, for instance, in a hotel or office building where it was necessary to get conversation out . . . we could walk through it when no one was in the corridor. By pressing the cane right up against the wall, the sound would come right through the cane, through a little wire up into our sleeve into a little pocket amplifier, and then into an earplug that permitted us to hear all that was being said in the room. Not only hear what was going on, but with another device that we carried we could transmit the same conversation to an automobile outside where recorders would make a permanent record of the conversation. . . . It's always interesting what goes on when people don't know they're being listened to.75

Vaus was the first to admit that his miniature microphones and "talking canes"—variations on the detectaphones and spike mikes used in the Goldman and Silverman cases—seemed "a little on the fantastic side" to the uninitiated.76 But they were real, they were effective, and they enabled him to corner a growing market for private eavesdropping work in Hollywood during the late 1940s. On top of his freelance police efforts, Vaus was hired in this period to tap the phones of L.A. businesses and record the conversations of state political candidates. He also accepted a $500 offer to bug Mickey Rooney's wife, whom the comedian suspected of infidelity. (Rooney was right, as it turned out.) Eventually, Vaus's skills came to the attention of the L.A. mob boss Mickey Cohen. After Cohen made Vaus a lucrative retaining offer, Vaus abandoned part-time police work and jumped headfirst into the world of organized crime. Over the course of eight eventful months, he made a small fortune tapping lines, planting bugs, and operating state-of-the-art electronic security equipment for Mickey Cohen's syndicate.

All of this would change on the afternoon of November 7, 1949. In between sessions of a grand jury investigation of the LAPD Vice Squad—a high-profile inquiry that hinged on telephone recordings that Vaus was alleged to have made on Cohen's behalf—Vaus went to see Elia Kazan's popular racial passing melodrama Pinky (1949), starring Jeanne Crain. Perhaps it was the pressure of the grand jury investigation. Or perhaps, as Vaus's wife, Alice, later suggested, it was Crain's portrayal of "a girl who pretended to be something she was not, just as Jim was bluffing about being . . . as good as the next fellow."77 Whatever it was, Vaus abruptly left Pinky and drove straight to Billy Graham's "Canvas Cathedral" on the corner of Washington and Hill Streets, just outside of what was then L.A.'s business district. After listening to one of Graham's fiery sermons, Vaus knelt in the sawdust, prayed for forgiveness, and was reborn. "I made a decision to accept Christ and his teachings," he told the Los Angeles Times the following week. "This has brought an entire change in my life. I have given up all my former work in crime and politics. God has changed my life and whereas in the time past I have lied and cheated men and women in this city, I propose . . . to live fearlessly for Christ and make amends for the many wrongs I have committed."78 God was calling, and Vaus, the expert wiretapper, was suddenly listening in. His religious awakening made national headlines.79

Vaus's conversion turned out to be instrumental in Billy Graham's rise to prominence during the early 1950s. (Incidentally, so did the conversion of Jeanne Crain's co-star in Pinky, Ethel Waters.) Here was a well-known Hollywood gangster who had renounced a life of crime to be born again, all on account of a sermon at a Billy Graham tent revival. The story provided an opportunity to spread the evangelical gospel, and the Billy Graham Evangelical Association (BGEA) proved quick to exploit it. In 1951, the Navigators, a BGEA-affiliated religious group, helped Vaus publish Why I Quit Syndicated Crime: The Wiretapper's Own Story (1951), a book-length testimony of his journey from sin to salvation. Featuring a fulsome preface written by Mickey Cohen himself—certainly the only book in history to claim this honor—Vaus's autobiography proved successful among evangelicals in the United States.80 It also went through a number of foreign language editions.81 After Alice Vaus published a companion volume, They Called My Husband a Gangster (1952), the BGEA's Hollywood production division, World Wide Pictures, arranged to adapt Vaus's story for the silver screen. The film was eventually released to theaters as Wiretapper (1955), starring Bill Williams as Jim Vaus and Georgia Lee as his devoted wife, Alice (see Figure 4).

Wiretapper is worth examining in some detail, even if the film does little more than recapitulate the most sensational episodes in Vaus's autobiography, from his ignominious stint in the military during World War II to his religious rebirth at Billy Graham's Canvas Cathedral. (Notably, Vaus's exploits with the LAPD are omitted from the film altogether.) As with all of the movies that the BGEA backed in this period, Wiretapper was primarily the product of a proselytizing impulse. If the lesson of Vaus's transformation wasn't clear enough on its own, the film's climactic conversion sequence featured an appearance by Graham himself, who delivers a version of the sermon that led to Vaus's religious awakening in November 1949 (see Figure 5). "There's a man somewhere in this audience who has heard this message many times before, and the spirit of God is striving mightily with him at this moment," Graham exhorts at the end of the film, speaking as much to Bill Williams's Jim as to the audience in the theater. "If he doesn't come to Christ now, he may never come. . . . There's still time for you to come. You come, and give your life to Christ." Jim gives his life, of course, and the film concludes as he renounces all worldly ties. He breaks with his criminal connections, surrenders his material possessions, and dedicates himself to God's service.

As a patently transparent example of American evangelical propaganda, Wiretapper doesn't seem to warrant much in the way of analysis. But as an episode in the public history of electronic eavesdropping, the film provides much more interesting fodder. For one thing, Wiretapper represents a notable link in long chain of historical connections between eavesdropping and American religious culture that runs from the nation's first major wiretapping scandal in 1916, which involved illegal police taps on a prominent group of Catholic priests in New York City, to Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation (1974), which figures the morality of electronic eavesdropping as a question of spiritual faith.82 More importantly, for our purposes, Wiretapper's portrayal of midcentury eavesdropping practice turns out to have been curiously exacting. Notwithstanding the BGEA's religious message, the film actually broke new ground in exposing mass audiences to listening techniques that had escaped the public's attention during the wiretapping controversies of the early 1950s. This is evident from the film's opening title sequence, which begins with a slow dolly shot into an open telephone junction box. As a flashlight shines down a row of terminal switches, a disembodied hand enters the screen to connect a thin pair of wires—one of the earliest authentic depictions of a direct wiretap in U.S. film history. This sequence is repeated later on in the movie, when police catch Jim listening in on a Hollywood prostitute's telephone conversations (see Figure 6).

In another scene, Jim is shown searching for a miniature microphone hidden in the home of Charles Rumsden, the film's fictional stand-in for Mickey Cohen. The episode draws heavily on Vaus's autobiography, which early on offers a vivid description of the sorts of listening devices that law enforcement agencies began using in the late 1940s: "These [hidden] microphones are difficult to find. They are very small, and are often buried between the two thicknesses of a wall. The wires that connect them are no larger than a human hair. Usually the wires are tucked into the cracks or crevices of the wood so that it is impossible to locate a microphone just by looking for it."83 To accentuate the size of the device on screen, the camera once again dollies in for a close-up. As Jim works to dislodge the bug we are afforded a better sense of scale: the microphone is only slightly bigger than his thumbnail. The film also includes similar shots of a working pen register, a wire recorder, and Vaus's trusty "talking cane."

Wiretapper's attention to technical detail provided the American public with its first glimpses of the bugging devices that Vaus and other eavesdropping specialists had pioneered in the wake of the invention of the transistor. The technologies were part of the film's appeal. As one reviewer punned, while Wiretapper's didactic storyline was likely to "short circuit" most movie-goers, the film's "fascination with machinery and gadgets" was more than enough to sustain audience interest.84 But it's crucial to note in this account that the electronic innovations showcased in Wiretapper—the miniature microphone, the pen register, and the "talking cane"—are registered as benign technological novelties, occasions for wonder rather than causes for alarm. These are ingenious devices that "defy known physical laws" and "hear the seemingly unhearable," as Vaus put it in his autobiography, and they variously brand Jim as a "young Edison," a "whiz kid," and a "magician" at crucial points in the movie.85 In certain respects, Vaus is represented as a technological miracle worker in Wiretapper. His electronic expertise provides a quotidian analogue to Billy Graham's spiritual gift, which essentially allows Graham to overhear Jim's private crisis of conscience at the end of the film. Perhaps it isn't surprising, then, that Jim's melodramatic conversion from wayward wiretapper to born-again Christian seems plausible in the movie. In Wiretapper, eavesdropping is a form of the Lord's work.

The idea that electronic eavesdropping devices were technological miracles, symptoms and symbols of God's hand in the world, eventually emerged as the foundation of Vaus's crusade as an evangelical Christian. In the years that followed the publication of Why I Quit Syndicated Crime and the release of Wiretapper, Vaus traveled around the country to deliver testimonies of his conversion experience to evangelical congregations (see Figure 7). His mission, according to one report on his exploits, was to "tap the souls of the sinful."86 Vaus's sermons in this period typically recounted the details of his life in organized crime and subsequent spiritual transformation. And true to his portrayal in Wiretapper, he frequently used electronic eavesdropping equipment to illustrate the Christian moral of his story.87 According to a 1953 article on a revival meeting in southern California, Vaus's "crackling electronics displays" were invaluable demonstrations of "points of religion. . . . It's a new idea, explaining God in terms of the amazing modernity of electronics and explaining electronics and science in lay terms."88 One of Vaus's devotees in upstate New York offered a more animated response to a 1956 sermon, once again connecting eavesdropping technology with the miraculous and divine: "He's . . . got a trunkful of gadgets with which he performs what look . . . like downright miracles!"89 In real life, not just on screen, Vaus's electronic eavesdropping devices seemed wondrous, almost godlike.

This was by no means a fringe assessment. During the 1950s, American news outlets frequently reported on eavesdropping devices as miraculous feats of technical ingenuity, particularly after the transistor began revolutionizing the field. In 1955, the same year Wiretapper appeared, Science News Letter ran an article titled "Tappers Called Ingenious" that marveled at the ability of professional eavesdroppers to "develop equipment for their trade so advanced . . . that some systems are similar to secret military devices."90 Newsweek likewise represented the nation's growing population of bugging experts as "inspired tinkerers," citing Vaus's work directly and quoting an anonymous FBI official who clearly admired (and likely profited from) the creativity of men like him: "It's amazing what they'll come up with."91 Vaus's "No Place to Hide" theme also resonated in more secular contexts. As Bernard Spindel explained in a tell-all article for Collier's in 1955, the discovery of the transistor made it impossible to live beyond the bug's reach:

To be completely safe against electronic eavesdropping today, you would have to construct a special conference room deep in the interior of a large building. The room would have to be windowless to protect it from the parabolic microphone (whose dish-shaped 'ear' can pick up and amplify conversations through open windows from some distance away). The room would have to be encased in heavy metal to thwart any still-secret eavesdropping devices set up outside the room and to reduce the effectiveness of any radio transmitters hidden inside. Within the metal sheath there would have to be an inner shell of transparent plastic, separated from the metal by about six inches and resting on transparent plastic supports. This would foil contact microphones which, when placed against a resonating surface such as a nail driven through a wall, pick up conversations on the other side of the wall. Moreover, all the wiring in the room would be visible through the plastic shell; any tampering with the lines would be immediately apparent. There would, of course, be no telephones.92

In the mid-1950s, Spindel's imaginary safe haven wasn't a nightmare prediction of a society without privacy. It was a thought experiment, intended to enumerate what was technologically possible in the age of transistor miniaturization. The miracles of electronic engineering made it such that bugs could operate anywhere, free of detection. From the junction box to the pulpit, and from the pulpit to the silver screen, Vaus's career provided evidence of that seemingly improbable fact.

The rhetoric surrounding electronic eavesdropping shifted in the coming years, and no figure embodied that shift more than Vaus's successor in the public eye, Harold Lipset, a bugging pioneer whose exploits in the field of private investigation during the 1960s came to personify the frightening reach of concealed listening devices. Born in Newark, New Jersey, and educated at the University of California, Berkeley, Lipset began his career as a freelance detective while serving in the U.S. Army's Criminal Investigation Division.93 He earned a bronze star for investigating crimes committed by American soldiers during World War II, and in 1947 he returned to the Bay Area to open a licensed private investigation firm. By the mid-1950s, Lipset had already made his name as America's "super snooper," routinely working more than 500 cases a year. He cemented his reputation by using electronic eavesdropping devices to help solve them.