Gendered Terrain: Middlebrow Authorship at Midcentury

My mother-in-law was a voracious reader who came of age in the early 1950s.1 Once, when I was putting together a class on postwar popular fiction, I asked her what she thought of James Jones's 1951 novel From Here to Eternity. "A great book, and an even better film," she said. "I remember it was my favorite novel for a time." Then I asked what she thought of the 1956 novel Peyton Place, by Grace Metalious. "Oh, Anna," she frowned. "You're not reading that, are you? It's absolute trash."

As it happens, the novels with which James Jones and Grace Metalious launched their careers were surprisingly similar in many ways. Both From Here to Eternity and Peyton Place featured sweeping plots with large casts of characters and shifting narrative perspectives. Both employed idealistic young protagonists to critique the hypocrisies of major American institutions, as well as tragically trapped but likeable secondary protagonists struggling toward integrity. Both were greeted with early critical acclaim before quickly becoming colossal paperback bestsellers, and both were soon made into Oscar-nominated films. Both took risks and provoked controversy, pulling their authors into the pages of popular magazines like Life and Look. And yet, as my mother-in-law's language suggests, From Here to Eternity and Peyton Place are recalled in very different terms. What explains their diverging trajectories? One answer may be found in the way gender functioned in the uneven terrain of the midcentury middlebrow.

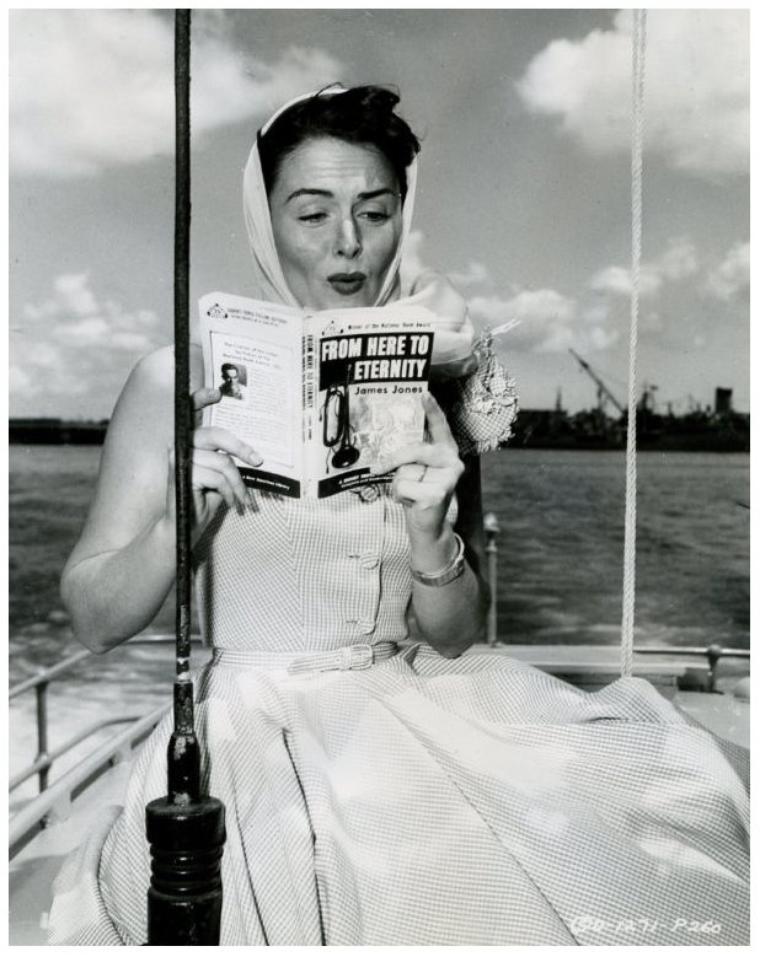

Figure 1: Actress Donna Reed (playing Lorene/Alma), reading From Here to Eternity on location in Hawai'i. Publicity still.

Middlebrow publishing and its institutions were forces to be addressed by midcentury authors struggling to establish literary footholds. Those forces produced anxieties that both aspiring authors and their readers had to manage, often in and through the deployment of gender. To James Jones, certain middlebrow literary institutions held distinctly feminine associations. Within his novel about the prewar military, James Jones embedded misogynistic critiques of the varieties of writing and reading he hoped to avoid. Beyond the pages of his novel, Jones leveraged a macho authorial persona to try to position himself outside the writing practices that threatened him. Grace Metalious, like Jones, hoped to use her fiction to "tell the truth" about the dangers small-minded American communities presented, especially for women. Purposefully stirring up gender trouble in the pages of her novel, she wrote about sex and violence with bold realism to press back against the prim conservatism of the times. The gendered resistance of her plots was escalated by her unladylike and irreverent self-presentation. But the powerful double standards of the times for men and women meant that these novelists' similar strategies would be received differently. Jones's masculine posturing kept him successful with both male and female readers, while Metalious's gender insubordination landed her in a literary rut not unlike the one Jones ridiculed in his fiction.

This paper considers the conditions of production and reception for two midcentury blockbuster novels whose status as highbrow, middlebrow, or lowbrow was never stable. The mutability of these novels' reputations is itself evidence that at this time, the middlebrow was a shifting ground. The middlebrow could be profitable for publishers and a safe space for readers, but, increasingly maligned by critics, it was treacherous territory for writers. While a variety factors shaped the careers of Grace Metalious and James Jones, this paper compares their similar debuts to highlight the ways gender and class converged to make postwar literary reputations in the middlebrow milieu. As these cases illustrate, the gendering of middlebrow culture etched high-low distinctions onto a growing middle class in ways that mattered and that lasted.2

The Middlebrow Designation

To contextualize this tale of two blockbusters, we must first frame the sudden re-emergence of the middlebrow in the decades following the end of World War II. Why, at this juncture, did middlebrow become newly necessary as a way to describe American writing and reading practices? The middlebrow designation has a very specific history: born in interwar Britain, its infancy prolonged by the crisis of World War II, the term exploded in U.S. popular discourse in the immediate postwar decades, in tandem and in productive tension with the consolidation of midcentury modernism. The middle brow in the US aligned with the postwar growth of the middle class, as rising affluence and education levels combined with a paperback revolution to produce a consumer culture that included the purchase of books, whether for pleasure, for status, or for show.

The post-World War II genealogy of the term "normality" is useful to consider here, since the term middlebrow experienced a similar tension and followed a similar arc. The postwar focus on a "return to normal," as I have argued elsewhere, signified an alignment with the "middle," which was imagined to be a sort of comfortably invisible in-between.3 But as more prescriptive notions of normality took hold, a potent critique of the concept emerged. In full swing by the early 1960s, this critique cast normality as dangerous: an "unambitious" conformity verging on communism. Normality was frequently feminized in this critique, as a complacency that was not just dull, but anti-modern, and an impediment to progress: "cheerfully unambitious, happily in a rut, is this the ideal for which to strive?" one writer complained in her diagnosis of "the 'normal' wife." 4 The discourse on the middlebrow followed a similar path, as the middlebrow's function also expanded, from describing audiences to texts to culture.

Middlebrow appears in American mass media at first as a relatively benign label, almost democratic in its appeal. Published discourse appearing before and during World War II used the term with less judgment, often simply to describe large audiences. "Middlebrows" composed only one among many demographics, and writers even emphasized the relative newness or constructedness of the category with the use of scare quotes. Middlebrow was a wholesome space which bore neither the snoot of high culture nor the smudge of low, and its defining quality was neutral, even statistical. A 1926 New York Times review, for example, promoted the utility of the term, and praised "middlebrows," slyly, for their purchasing power: "It is a word, or at least a conception, which ought ... to gain currency.... They are not a distinguished body, even in their own most complacent judgment of themselves, but they are useful... [T]he great mass of the middlebrows [are], after all, the great encouragers of literature by not only reading books, but buying them."5 In such early discourse, middlebrow was a noun, not an adjective, and "middlebrows" were valued as a critical "mass." Middlebrows were simply the "middle," and the term helped to explain cultural forms with broad appeal. Fairly quickly, historically speaking, it began to be used with skepticism.

By the late 1940s, the term "middlebrow" became less benign and more pointed, and was increasingly used as an instrument for skewering literary texts. One 1947 New York Times reviewer, for example, defined the middlebrow as "writing [that] troubles to be good" but is not "of the first order."6 Defenses of the middlebrow persisted, particularly by publishers like John Farrar for whom it was profitable to encourage expansive literary tastes: "It would be a bore for me to publish only for the 'highbrow.' I like the 'middlebrow.' I like the 'lowbrow.' I have always despised the literary snob. I like a good story and I am bored by a pretentious, dull book, no matter what scholarly cloak it wears."7

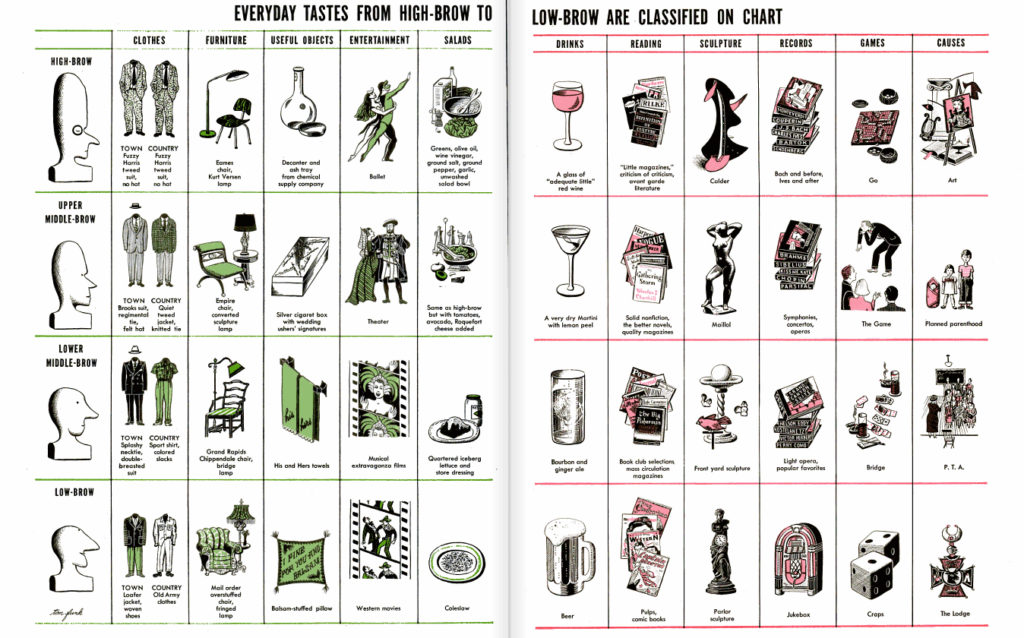

Into this space between middlebrow's uncertain literary value and its broad marketability entered Russell Lynes's infamous 1949 Harper's article "Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow," to make its own far-reaching masscult ripple.8 A slice of what would become Hynes' book-length study The Tastemakers (1954), the essay "Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow" was quickly reprinted in Life magazine, complete with a "socio-diagram," a cheeky illustrated taxonomy of American taste from furniture to cocktails to salads to reading material.9 With its wide dissemination, Lynes's somewhat satiric shorthand helped solidify the terms of debate: after 1950, middlebrow would not only describe audiences or texts, but all aspects of culture and taste. Significantly, Lynes further divided the designation — or rather, claimed that middlebrows "divided themselves" — into "upper-middlebrow" and "lower-middlebrow." This splitting of the middle both played on midcentury anxieties about class mobility and helped an already-exaggerated gender binary to become a part of the middlebrow. One of Lynes's subsections, entitled "Women in Charge," flatly stated that "in the matters of taste, the lower-middlebrow world is largely dominated by women." Another of Lynes's sources blithely gendered the highbrow male with the remark, "A highbrow is a man who has found something more interesting than women." The lower-middlebrows, according to Lynes, were the ones who were "the members of the book clubs," the undiscriminating consumers who "read difficult books along with racy and innocuous ones."10 Since highbrows and lowbrows at least had some common cause, the lower-middlebrow really occupied the consumerist bottom rung by Lynes's calculations: "It is the upper-middlebrows who are the principal purveyors of highbrow ideas and the lower-middlebrows who are the principal consumers of what the upper-middlebrows pass along to them."11

Figure 2. Russell Lynes, "Everday Tastes from High-Brow to Low-Brow are Classified on Chart," Life Magazine, April 11, 1949, pp. 100-101.

Lynes's bifurcation of the middlebrow at midcentury was a key development, and characteristic of the age. According to the chart, highbrows read "'little magazines,' criticism of criticism, avant garde literature"; upper middlebrows read "solid nonfiction, the better novels, quality magazines"; lower middlebrows read "book club selections, mass circulation magazines"; and lowbrows read "pulps, comic books." The taxonomy of brow-heights that he produced, tongue-in-cheek as it was, "almost became a national parlor game," according to one critic.12 At a moment when, according to one study, 40% of Americans defined themselves as middle class and more than 50% as working class, Lynes encouraged readers to make high-low distinctions within the middle, a demographic that was growing so large as to threaten to become meaningless — or dangerous.13 After Lynes, discourse on the middlebrow would proliferate throughout the 1950s, as the designation took stronger hold as a pejorative. In literary culture, such divisions would help draw lines between "good" books and "trash," or what one critic by the late 1960s called "middlebrow meretriciousness."14

This ruptured ground was the space in which so many midcentury authors like Jones and Metalious would make their debuts. As books became both explosively popular and aggressively policed by powerful arbiters of taste, the boundaries imposed on writing and reading practices would not only reflect but also help constitute midcentury American class and gender boundaries.15

Middlebrow Plots

The term middlebrow can be maddeningly nebulous, but it is important to note at the outset that I see it as extrinsic rather than intrinsic to texts. In other words, as Nicola Humble has argued, "there is no such thing as 'middlebrow literature.' It is a category into which texts move at certain moments in their social history."16 Rather than a particular set of textual characteristics, middlebrow is a historically situated category deployed by critics and institutions to label texts or readers. In this sense, middlebrow describes function more than form.17 Other scholars, however, have countered that middlebrow fictions share certain formal qualities, or at least constitute a coherent literary project. Such qualities might include a "hybridity" of high/low reading experiences (Humble), recuperative endings (Wood), a character-driven realist style (Studer and Takayoshi), middle-class perspectives (Brown), or even pragmatic social critique (Harker).18 It is worth noting that both From Here to Eternity and Peyton Place would satisfy middlebrow categorization in any of these terms.19 But I would maintain that middlebrow institutions and reading practices shape the reception of texts as middlebrow in their own eras.

A comparison of the plots of these two first novels suggests a number of features in common. Jones's 800-page realist novel draws heavily on his experience as a World War II Army veteran, and it is boldly critical of the conformism of the American military. Focused on "G-Company," a peacetime Army unit stationed in Schofield Barracks, Hawai'i, in the months prior to Pearl Harbor, From Here to Eternity centers on Robert E. Lee Prewitt, an undereducated, poor-white Kentucky coal miner's son who has fumbled his way into the Army because "[a] man has got to have some place."20 Strong-willed and individualistic, Prewitt endures an escalating series of punishments for his independence, including torture at the hands of a sadistic stockade sergeant. The central story of Prewitt's eventual martyrdom is interwoven with the story of his love affair with a white prostitute called Lorene (born Alma). The remaining characters form a classic World War II multiethnic platoon, and spend most of their time bonding, fighting, gambling, drinking, visiting brothels, or "queer rolling": exchanging drinks or money with gay men in Waikiki for sexual favors. Jones develops a second narrative about the seasoned Staff Sergeant Milt Warden, who remedies his boredom and disillusionment with an affair with Karen Holmes, the equally bored and disillusioned wife of his superior. Prewitt's story ends in violence: going AWOL after murdering a sadistic stockade sergeant, Prewitt hides out in his girlfriend's house but is shot and killed by MPs while trying to return to his post to fight as the Pearl Harbor attack begins. The novel ends with Lorene/Alma and Karen Holmes meeting as they sail home to start carefully reconstructed lives on the mainland.

Metalious's long novel, though half the page count of From Here to Eternity, weaves together the stories of three major female characters: Peyton Place is a bildungsroman for young aspiring writer Allison Mackenzie; it is a tragedy-turned-around for Allison's impoverished and abused friend Selena Cross; and it is a sexual salvation story for Allison's self-made single mother, Constance Mackenzie. While set between the depression and World War II with a huge cast of characters, the novel's social critique is aimed squarely at the bourgeois hypocrisy of the 1950s, particularly the burdens that culture placed on women's sexual and psychic freedom. Drawing details for her story from her imagination, novels she loved, local headlines, and the lives of her neighbors, Metalious rendered the collectivized and harshly judgmental "voices of Peyton Place" alongside the interior lives of citizens suffering from the town's neighborly surveillance.21 Allison Mackenzie, struggling with her own sexual and artistic identity in a culture of silence and dishonesty, liberates herself by leaving Peyton Place for a writer's life in New York. Despite a life of poverty, violence, and sexual abuse at the hands of her stepfather, Allison's friend Selena Cross, surviving an unwanted pregnancy, an illegal abortion, and a murder trial, fiercely chases and finds success and economic independence. While thriving as a single working mother, the "widow" Constance Mackenzie (who actually had Allison as the result of an affair with a married man) has to free herself from her own obsession with keeping up appearances in order to find sexual pleasure and personal integrity in a new marriage. Although both Allison and her mother end the novel in or approaching heteronormative pairings, the working-class character Selena Cross remains happily single and self-sufficient, managing Constance's shop.

Jones and Metalious each produced complex narratives that could and did appeal to a broad cross-section of readers. While Jones's plot critiques the anti-individualist hypocrisies of a military that destroys its own strongest adherents, Metalious's plot critiques the anti-individualist hypocrisies of middle-class communities that destroy their own best citizens. Both authors located their stories in the months or years leading up to World War II, making them both, in a sense, novels designed to process the deep reverberations of the war, as well as the depression that preceded it. Notably, both authors pushed the envelope in using raw language and in writing more explicitly about adult questions or themes, especially the realities of sex. From Here to Eternity exposed the sadistic practices of the Army as well as the sexual permissiveness of the homosocial military environment, while Peyton Place broke silences around such feminist topics as female sexual desire and pleasure, birth control and abortion, child abuse and incest, and domestic violence and suicide.22 In the end, despite the fact that Jones wrote amply about sex and Metalious wrote disturbingly about violence, Eternity would be framed as the war novel, and Peyton Place as the sex book.

Figure 3. Peyton Place, first hardback edition, 1956. From John Unsworth's "20th-Century American Bestsellers Database," Department of English, Brandeis University.

Representations of reading practices within the novels help to reveal the relationship each author had to the middlebrow milieu. Both Jones's and Metalious's protagonists experience "insatiable" pleasure, intellectual growth, and personal understanding through reading. Jones's novel contains many evocative scenes of characters reading or discussing reading, scenes which illuminate the gendering of midcentury middlebrow culture. In one pivotal "queer rolling" scene, for example, the hero Prewitt and his friend Angelo Maggio pay a visit to "a little side street" in Waikiki with their respective "dates," two gay men named Tommy and Hal. The burly Tommy writes short stories, and Hal is an effete novelist. As if the correlation between gender, sexuality, and authorship were not clear enough, Jones has Hal pontificate on the matter: "We're abnormally sensitive..., you see? Homosexuality breeds freedom, and it is freedom that makes art" (367). Prewitt, out on a "queer" date for the first time and unsure of how to interact with these men, launches into a discussion of writing and reading with Tommy. In the chic "neatness and the order and the niceness of [Hal's] apartment," a space which includes "chrome and real leather modern chairs," a record-player, and "a big bookcase that was full, and a well-desk," Prewitt begins to learn that a certain variety of authorship and reading aligns with both effeminacy and middle-class consumption. The scene's dialogue clearly telegraphs James Jones's own view of the middlebrow literary culture in which he was trying to make his macho mark:

"Have you ever had any of your writing published?" [Prewitt] asked [Tommy] finally.

"Of course," Tommy said stiffly. "I had a story in Collier's just a few weeks back."

"What kind of a story was it?" Prew was looking at the records, all classical, symphonies and concertos.

"A love story," Tommy said.

Prew looked up at him and Tommy giggled in his deep bass voice.

"Story of an aspiring young actress and a rich young Broadway producer. He married her and made her a star."

"I can't read them kind of stories," Prew said. He looked back at the records.

"I can't either," Tommy giggled.

"Then why write them?"

"Because people want to read them, and will pay for them." (369-70)

Employing his gay characters as vehicles for a debate about cultural value, Jones lets his hero Prewitt play the naif, confused by Tommy, a consumer of highbrow culture (the classical records) who produces mass culture that he would not deign to consume. In their exchange, Tommy reveals that he writes romance stories for middlebrow magazines with a mercenary purpose. His variety of salesmanship is not so far removed from what Prewitt is engaged in by "dating" gay men in Waikiki: these men are both, as Jones would likely put it, prostituting themselves for money. As their discussion continues, Prewitt tests Tommy further, questioning his talent for writing realistically:

"They aint [sic]23 like real life though," Prew said, "Nothing like that crap ever happens."

"Of course not," Tommy said, stiffly. "Thats why the people read them. You have to give the people what they want."

"I aint so sure that they want that," Prew said.

"What are you?" Tommy giggled bassily. "A sociologist?"

"No. But I figure I'm about like most people. I don't know nothing about great literature, but I cant read them stories."

"Its not the men," Tommy said. "Its the women. The stupid, romantic, filthy, moralistic women. They're the ones that like it. They are the book and magazine buyers. And they eat it up. They have to get their kicks some way, dont they? Their morals wont let them get their kicks in bed."

"Oh, I don't know. I aint convinced of that." (369-70)

Tommy defensively blames "the women" for the formulaic quality of middlebrow fiction, but Prewitt casts doubt on this logic. Jones's misogynistic strategy in this scene is to align the "giggling" queer Tommy with lower-middlebrow genre writing, and to align womanhood with unscrupulous reading. With the line "I aint convinced of that," Jones's "straight" man Prewitt implies that a sexually satisfied woman would not need the substitution of "them kind of stories." A true writer — by implication, a straight writer — would not "give the people what they want." This was just the sort of writer James Jones aspired to be.

Scenes featuring books and reading in Peyton Place also comment on the novel's relationship to the middlebrow, though with a different tone than those in From Here to Eternity. Metalious's characters read for a broader range of reasons, and their reading, less colored by class, sexuality, and gender than Jones's examples, crosses brows. One of the characteristics of dreamy adolescent Allison Mackenzie, for example, is that she is an "insatiable" reader, one who wishes to become a writer:

...she devoured every word she read and was filled with an insatiable longing for more. She discovered a box of old books in the attic, among them two thin volumes of short stories by Guy de Maupassant. These she read over and over again, unable to understand many of them and weeping at others.... Allison's reading had no pattern, and she went from de Maupassant to James Hilton without a quiver. She read Goodbye, Mr. Chips, and wept in the darkness of her room for an hour while the last line of the story lingered in her mind. Allison began to wonder about God and death. (46)

Whereas Jones has his hero learn to observe gendered hierarchies of literary value, Metalious's heroine Allison Mackenzie reads with "no pattern" and little regard for such hierarchies. She reads for both emotional and intellectual purposes, and as she moves toward sexual maturity, Allison reads more often alongside her friends, and for increasingly erotic purposes: "Kathy and Allison changed their reading habits radically that winter. They began to haunt the library in search of books reputed to be 'sexy,' and the read them aloud to one another" (92). With her friend Norman Page, Allison "swam and ate and read" books like Robinson Crusoe and Walden (226), until pubescence leads them to investigate anatomy books, raising the suspicion of Allison's uptight and paranoid mother. "I suppose you were off in the woods doing nothing but reading books!" exclaims Constance (236). In such scenes, reading itself becomes sexualized, as both Allison's reading practices and her early forays into writing are entangled with desire and a search for romantic fulfillment. With this trope, Metalious comments on the culture of sexual repression surrounding the novel itself, since Peyton Place— famously scandalous, banned, and ridiculed — would be received as the kind of subversive, sexualized reading her most repressed characters feared.

Middlebrow Production: Gender and Genre

The very intention to become an author was an exercise in bravado for James Jones, as one former Army buddy reminded him in a fan letter: "Do you remember telling me [in the hospital in Schofield Barracks, Dec. 1940] that if you were not successful as a writer within ten years that you would blow your brains out? This statement stayed with me...and so I was not surprised in early 1951 to read that your book [From Here to Eternity] had become a best-seller."24 Jones's text was a "literary phenomenon" in part because, like Peyton Place, it epitomized a new kind of publishing success story.

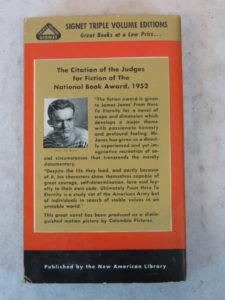

Figure 4. Signet 1953 "triple-volume" paperback edition of From Here to Eternity.

Signet's hardback edition of From Here to Eternity was promoted in Publisher's Weekly with a large advertisement and a photograph of the author on the cover in December of 1950. In khaki brown with a simple bugle image, the novel's cover art promised another in the emerging subgenre of World War II novels. The first edition's author's note emphasized Jones's military career almost exclusively, thereby highlighting both his respectability and the authenticity of his narrative. Early advertisements for the book featured blurbs from the "Editorial Board of the Book-of-the Month-Club" as well as from Norman Mailer, who claimed, "It's a big fist of a book... one of the best of the 'war novels.'"25 Jones's $100,000 payment from the New American Library far eclipsed Mailer's previous record of $38,000 paperback rights to The Naked and the Dead (1948),26 and after Columbia purchased the film rights to From Here to Eternity in March of 1951, the 1953 film went on to win eight Oscars and returned the novel to the bestseller list yet again.27 Even the very size of Jones's text seemed new, capturing the size-matters mentality of the masculine middlebrow. The NAL/Signet paperback edition had to be published in a special "triple-volume" format due to From Here to Eternity's extreme length.28 An endlessly long novel was not only a bold display of the hard labor undertaken by the writer, but also an affirmation of the middle-class status of readers who had the leisure time to spend on such "serious" books.

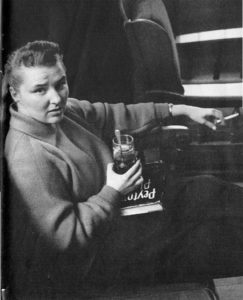

The wife of a poorly paid New Hampshire school principal, Grace Metalious famously let the dishes pile up in the sink and locked her kids out of the house in order to write Peyton Place. When asked if her next book would be "another Peyton Place" she replied, "I don't see how it can be. This time I'm neither frightened nor hungry nor angry."29 At a time of almost baroque cultural differentiation between male and female, Grace Metalious's public "appearance was as much of a scandal as the book was," as one reader recalled.30 In every way, whether it be her infamous "Pandora in Blue Jeans" book-jacket photograph in flannel shirt and jeans, or her so-called "coarse" irreverence during television appearances, or her "fat and happy" self-presentation in mass-circulation magazine features, or her snippy response letters-to-editors of small-town papers, Metalious frankly refused postwar cults of femininity, slenderness, stylishness, tidiness, deference, and consumerism. As with Jones's respectable-veteran image, this public persona mediated her book's reception.31 But in contrast to their celebration of Jones, the media cast Grace Metalious as a "freak": a housewife who "deviate[d] from the pattern" by writing a novel.32 Focusing on the supposed conflict between her gender and her authorship, the media pathologized her female masculinity to explain her capacity to author such a "dirty" book. In this way, while both authors leveraged masculinity as a tool to help them navigate the middlebrow milieu of postwar publishing, the same tool that would build Jones up was used to tear Metalious down.

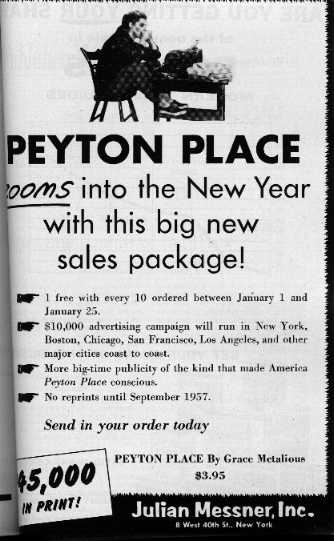

Metalious's novel was marketed through a contradictory appeal to both her respectable identity as a New Hampshire housewife and to the titillating promise of scandal. Metalious herself helped propel this scandal by suggesting in an early interview that her high-school principal husband was going to be fired because of the controversial content of her soon-to-be released book. The publicity team at Messner ran with the (largely exaggerated) story. One of the pre-publication advertisements featured an illustration of the hardback Peyton Place surrounded by torn-from-the-headlines newspaper stories: "Wife's Spicy Novel Gets Teacher Fired" and "Staid New England Town Shocked by Frank Novel," under the tagline "This is the explosive book that was headlined all over the country!" The strategy helped Peyton Place become one of the first novels to be a bestseller before its release.33 Metalious and Jones had each labored to write realistically about sex and sexuality, but the sexual content of Peyton Place was exploited, not downplayed by her publisher. James Jones's publisher (Scribner's) required him to delete explicit scenes focused on homosexuality and the brothels,34 but Metalious's publisher actually asked that she write an additional hetero sex scene between the adult couple Constance Mackenzie and Tom Makris.35 Fearing censorship, Metalious's publisher also required that Selena Cross's rapist father to be changed to a stepfather. At a time when the 1956 Miss America Bess Meyerson hid her own past as a victim of father-daughter incest, and Erskine Caldwell's incestuous undercurrents had become best-selling titillations, Metalious understood how such subtle distinctions could shape the high-low-trash distinctions of a literary career. Father-daughter incest was the stuff of tragedy, but randy stepfathers were the stuff of Dogpatch: it was a cliché so pornographically American that Nabokov had burlesqued it mercilessly in Lolita that same year.36 Metalious felt this requirement that Lucas Cross be changed to Selena's stepfather changed the incest plot in her novel from "tragedy into trash."37 Reviewers would continue to diminish the tragic element of incestuous abuse in Peyton Place as lowbrow, even calling the novel "Tobacco Road with a Yankee Accent."38 Though the marketing campaigns had emphasized the authenticity of both From Here to Eternity and Peyton Place by referring to their authors' lived experiences, Jones's truth was "bold," while Metalious's truth was "earthy."39

Figure 5. Julian Messner, publicity for Peyton Place. From John Unsworth's "20th-Century American Bestsellers Database," Department of English, Brandeis University.

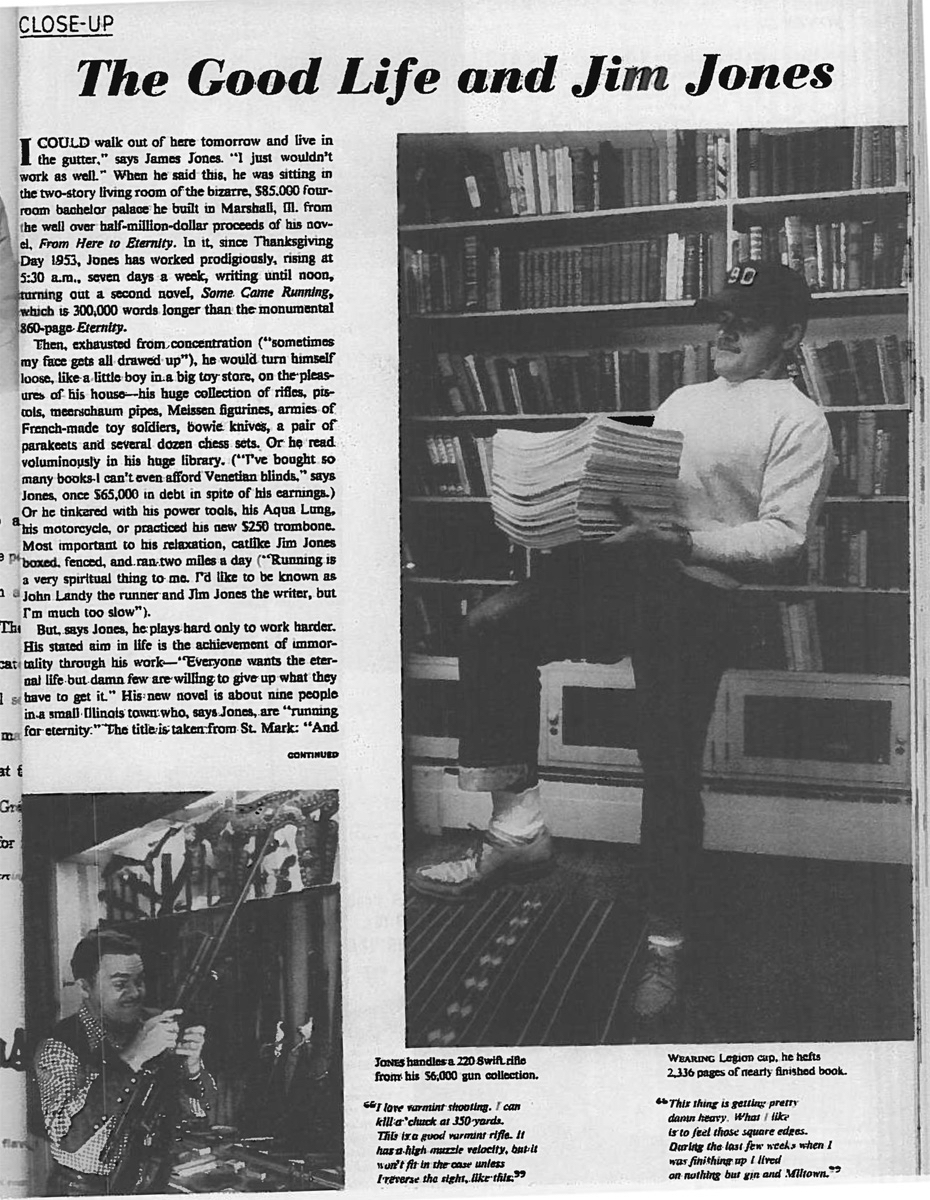

At midcentury, then, middlebrow publishing was increasingly packaging novels as "both works of art and commodities."40 Mass-market magazines, famously cast by Macdonald, Lynes, and other masscult critics as inherently "middlebrow" forms, produced glossy features on literary figures, helping to make their private lives part of their publishing lives. In 1957, Jones was the focus of a Life magazine feature which, along with other public portrayals, mediated the continued reception of his work: it re-ignited sales of Eternity and built an audience for his future novels.41 An indication of how powerfully middlebrow magazine culture could help make a literary career, this Life feature showed Jones hoisting his thousand-odd page Some Came Running manuscript, displaying his gun collection, and playing chess in his luxurious bachelor home, complete with a floor-to-ceiling library. In 1958, Metalious was the subject of a lengthy Look magazine feature. In contrast to the media's celebration of James Jones's hypermasculine domestic interiors, this feature showed Metalious in New England housewife mode, frolicking with her dogs outside her Cape Cod home or braiding her daughter's hair. But Metalious also resisted this stereotype by refusing to play pretty for the camera, and Look's Patricia Carbine certainly noticed, describing Metalious as as "a paunchy, pony-tailed woman without a hint of make-up.... with a long-sleeved jersey spanning her bulky girth.... [and a] high-cheeked but too pudgy face." This ruthless authorial portrait was indicative of a steady spotlight of media attention that not only shaped the reception of Metalious's writing, but in many ways, overshadowed it.42

Figure 6. Grace Metalious, photo by Bob Sandberg, LOOK Magazine, 18 March 1958.

Middlebrow Reception: Club Mentality

In a late scene in From Here to Eternity, the protagonist Prewitt, who has gone AWOL, hides out in his girlfriend Lorene/Alma's apartment, which she shares with another prostitute named Georgette. Georgette, Jones writes, "belonged to the Book of the Month Club, 'just for the hell of it,'" because, as she says, "'after all, I do live on Maunalani Heights, and the books look good in the livingroom even if I dont read them'" (659). By having a prostitute be a Book-of-the-Month-Club member who doesn't read her own purchases, Jones took another opportunity to satirize women's reading, middle-class status-seeking, and the pretense of middlebrow literary institutions.

At first Georgette's books are simply part of Prewitt's experience of the pleasure of middle-class interiors; they are luxury objects to be held, or beheld:

He would play through the records, and run through all the books, and go around feeling the furnishings, and feel the tile floor and the Jap mats on the porch with his bare feet, and in the evening he would make his own evening meal himself in the shining white kitchen where he knew just exactly where everything was. All the books with their brightly colored jackets (Georgette had been in the Book of the Month Club three years and she always took every book, plus all the dividends) were very pretty in the recessed bookcase over the divan...And there was all the time in the world. (659-60)

But with "all the time in the world," Prewitt begins to read and drink too much, and soon goes on a middlebrow "bender" of sorts, reading "every book in Georgette's Book of the Month Club collection,"

even the bad ones that did not sound true to life.... He read night and day like that for over two weeks. If the girls got up at noon, or came home from work at 2 AM, they would find him curled up in a book with the dictionary and a drink at his elbow. He had found that three or four drinks made many of them much more believable. He would be so engrossed that the girls never got more than a grunt for an answer. (688)

Though the self-educated Prewitt has to read with a "dictionary... at his elbow," Jones clearly casts this reading as middlebrow by invoking the Book of the Month Club, by emphasizing the books' value as decor, by leaving the authors nameless and the books themselves untitled and indistinguishable. Middlebrow reading becomes a feminized literary overconsumption that endangers our hero by making him both antisocial and uncritical.

When Prewitt runs out of Georgette's books, however, Alma brings him new ones from the library, and the gender of reading immediately shifts. Prewitt "remembers" how another soldier "had always talked about Jack London all the time," and although Prewitt has to "use the dictionary more often with London,"

he could still seem to read him faster... One day, ... he read five in one day... It was while he was reading Martin Eden that he got the idea to start writing down titles of other books to read, like Martin had done. There were lots of them in [Jack] London. Most of them he had never heard of... He wrote down all of them, with the author's name, in the little notebook he had had Alma buy for him. He would look at the growing list as proudly as if it was a Presidential Citation. Before he was done, he would read them all.... He did the same thing with a Thomas Wolfe book that Alma brought home on a hunch. (689-90)43

In both of these scenes, reading is linked to leisure time (he is bored), rebellion (he is AWOL), and consumption (he reads/drinks/reads/drinks himself into a stupor). The scenes explicitly describe reading as a class experience, but the class valences of reading are also clearly gendered. When Prewitt turns to the masculine-themed, male-authored fiction of London and Wolfe, he is no longer degraded, but uplifted. These books lead him to more of their kind, and become part of his erudition. These authors' names matter enough to be recorded and remembered. Taken together, these scenes construct middlebrow reading as gendered: women or effeminate men write lower-middlebrow fiction, and women read it. Lower-middlebrow is aligned with the prostitute Georgette's commoditized Book-of-the-Month Club collection, while the more upper-middlebrow Jack London and Thomas Wolfe bear the library's modern, masculine, literary distinction.

Ironically, in light of the way Jones's novel parodies it as a middlebrow institution, From Here to Eternity actually became a Book-of-the-Month-Club selection, though the Club decided to make it an alternate rather than a feature because of its "frankness." From Here to Eternity was also a 1952 National Book Award winner, besting The Caine Mutiny and The Catcher in the Rye for the honor. And the novel made Jones rich: according to Newsweek, he was "the most successful novelist in American literary history."44 These tensions among the institutionalization of a middlebrow book club, the prestige of a national book award, and the pop-culture element of mass appeal illustrate how fraught the making of any midcentury literary reputation could be.

Reviewers in the 1950s praised Jones's novel for its realism, but it was a gendered realism. They admired Jones for using the "moral and social order" of the Army to frame his story, thereby avoiding the "classless and mannerless wastes of American life into which so many of his contemporaries have wandered aimlessly and been lost." Critics complimented Jones's naturalism, which they saw as an antidote to the "effeminate" turn to a more "psychological" literature, and celebrated his exploration of universal problems like the "perversity of human nature in the face of evil."45 These reviewers, always male, particularly praised the authenticity of the "pungent dialogue" of Jones's "soljers" and praised the "integrity" and "punch" of his writing, "as exciting as a sock on the nose."46 James Jones had battled with his editor Burroughs Mitchell to include the profanity, which he felt brought him closer to the truth: "I am willing to cut considerable of it," he wrote to Mitchell, "but ... if you take it all out ... the whole thing is going to sound like a historical novel of the Amber ilk which cunningly hints at everything but never has the guts to say anything.... I dont care if anybody thinks I'm a dirty writer. Maybe I am. After all I've only my American background and training to pattern after."47 With this comment, Jones worked to distance himself from Kathleen Winsor's phenomenally successful 1944 novel (set in Restoration England) Forever Amber. While both novels could easily be described as popular, overly-long historical romances, by emphasizing his "gutsy" style of "American" prose, Jones claimed a masculine nationalist authority that suited his early Cold War context.48 The masculinist discourse propagated by both critics and Jones himself raises the question of whether Jones's career was in part facilitated by a masculine turn in the postwar middlebrow. In such an environment, the success of writers like Jones was to some degree made possible by the failures of writers like Metalious, and by the gendered containment of woman-authored and woman-centered books like Peyton Place in a separate sphere.

Peyton Place was a small-town stand-in for a national culture of keeping up appearances, and the power of Metalious's critique was not lost on the novel's early positive reviewers. The New York Times admired Metalious's fearlessness in calling out the "false fronts and bourgeois pretensions of allegedly respectable communities," and aligned her with such literary forebears as Sherwood Anderson and Sinclair Lewis.49 But the frankness of Metalious's text quickly became the locus both for the book's popularity and for a punishing shift in its critical reception. In the end, the same culture that had required more sex scenes to make Peyton Place a bestseller would condemn her for the scandal it caused: "People are surprised, Grace, that a book so full of sex and violence could be written by you, a housewife and mother of three children," as one wide-eyed blonde television personality put it.50 Jones's book, despite its equally explicit sexual realism, was praised in literary not moral terms, for its "extreme naturalism."51 One male reviewer for the New York World Telegram explicitly compared Metalious to Hemingway, James Jones and other "masculine writers who have refused to use euphemisms where four letter words will do," but then disparaged her for it: "never before in my memory has a young mother published a book in language approximately that of longshoremen."52 Female reviewers were just as violent in their policing, if not more so: Margaret Latrobe, for example, mocked the profanity of contemporary male authors (like Mailer and Jones, presumably) lest "Somebody might think writers were effeminate! Gad!" Metalious, Latrobe continued, "apparently wants to prove that women writers aren't effeminate either; that at least one can be just as ugly-spoken as any man writing."53 Again, the same quality praised in a male-authored text as authenticity was panned in a woman-authored text as vulgarity. Metalious's willingness to exercise "unquiet acts of female nonconformity" kept her under the microscope, and the public attraction/repulsion toward her would color the rest of her career.54

The middlebrow respectability of being a Book-of-the-Month-Club selection, combined with the prestige of winning the National Book Award, helped edge From Here to Eternity toward what Lynes called the upper-middlebrow. Peyton Place, by contrast, became increasingly infamous for being censored or banned, or simply for its unprecedented sales. By 1958 Peyton Place had outsold Gone with the Wind, and by the time the popular but quite dissimilar television serial debuted in 1964, the novel had sold more than eight million copies, to become America's all-time fiction bestseller. Since roughly one in twenty-nine Americans purchased the novel and countless more read it, Peyton Place was understood less on its own terms and more in terms of the consumption patterns of the masses.55

Fan Feeling

In the surveillance culture of the 1950s, the middlebrow zone between high and low, between egghead and pulp, was popular with readers because it was safe. The voice of postwar criticism was powerfully present, not only in the pages of the New York Times or Partisan Review, but in mass-market magazines as well, so people read books with an increasingly intense awareness of what reading signified.56 James Jones understood that mere ownership or possession of books could be enough to perform middle-class respectability, and he pointedly used female characters to condemn this pretense of being well-read. In so doing, he flattered both male and female middle-class readers who were working to join a reading class, as opposed to simply a book-buying one. Although Metalious also engaged in such debates over taste and class, she did so with powerful public zingers like "If I'm a lousy writer, a hell of a lot of people have got lousy taste."57

While shame was attached to certain kinds of reading, that shame did not necessarily prevent the reading. Younger readers shared Peyton Place in the manner of Allison Mackenzie and her friends: they gathered around the novel in secretive places to read only the most erotic scenes, such that reading itself practically became a sex act. Their parents hid copies of Peyton Place in brown bags or under their beds, like illicit booze.58 As the paperback revolution made books more available and affordable, soldiers passed books around Army barracks, and commuters tore the covers off to read books on the train, free of judgment. And many families did present artful arrangements of hardback fiction in their living rooms or dens, for picture-window approval. These reading practices were more complex, however, than the sort that Jones had critiqued with his narrow representations of self-hating writers like Tommy and his unscrupulous women readers, or hypocritical Book-of-the-Month-Club posers like the prostitute Georgette. Dwight Macdonald had expressed concern that middlebrow culture would "fuzz up the distinction" between mass and high culture, and postwar readers bore this concern out by crossing brow-boundaries, though not without apology, and not without consequence.59

When readers become part of the terrain of the midcentury middlebrow, it shifts yet again. Fan mail response to From Here to Eternity suggests that for some, the novel's success was tied to readers' understanding themselves through it. Military readers closer to the book's 1951 debut connected to Jones's tale with a poignant immediacy: "I just this minute finished reading your great book, 'From Here to Eternity.' As I write this, I am sitting 'on watch' in the Navy radio station at Wailupe -- only it's a Coast Guard station, now.... Anyhow, thanks from an ex-Army man in the C.G. for a few hours of damned good reading." Another fellow veteran wrote, "As I am not an accomplished writer, I have only written my own past history to let you know how profoundly I was touched by your book... I like to read myself and your book in my estimation ranks as one of the outstanding books of the 20th Century.... P.S. This is the first fan letter I have ever written in my life."60 These moments of personal connection suggest the degree to which reading From Here to Eternity was about masculine self-identification. The missing comma and double meaning of "I like to read myself" is a subtle, inadvertent signal of this phenomenon: "I like to read, myself" becomes "I like to read myself." The self-ish, self-interested mirror function of middlebrow reading is transparent here, and is especially relevant in letters from one veteran to another.

Women read this book too, in larger numbers than one might expect: an unscientific survey of fan letters in the Beinecke archive showed that roughly forty-three percent of correspondents were women. A large proportion of these fan letters to Jones were inspired by the 1957 Life magazine feature that had highlighted the middlebrow-masculine persona that Jones embodied so well, with his massive book manuscripts and juxtapositions of books and guns casting reading as serious man-sport. But these letters also indicate how middle-class respectability was central to Jones's broad appeal to women readers. "Perhaps I should be writing Life magazine instead of you," writes one female fan. "It was very inspiring to read of your interests and more important your possessions. To be specific -- your library. All I can say is, thank Heaven for public libraries."61 Another reader, an African-American woman, tells Jones her entire life story, then eventually (like a number of others) asks him for a loan, saying "I guess I am one of those you write about that wants eternal life but isn't willing to give up anything to get it, because I want a few more of those material things everyone's crying for."62 Such responses reveal the ways the middlebrow milieu linked books to consumption and to social mobility. Charting the boundaries between high and low themselves, many fans flattered Jones (and perhaps themselves) by aligning him with Tolstoy or Conrad, and celebrating his accomplishment as the "one of the outstanding books of the 20th century."63 Others, like one woman reader from Charleston, South Carolina, complained about the debased purposes to which Jones had put his talents: "After reading the write up about you in Life, I rushed out and got your book ... Frankly, I was surprised that a book with such vulgar language could have been sold to the American people. - I was shocked that people actually read what I consider trash."64 Most male readers, however, like most male critics, continued to defend the macho tone Jones projected in his Life portrait as well as in his novel. One male fan, an aspiring writer, rehearsed his and Jones's "mutual" interests, including skin diving, motorcycles, "dames" and guns, but with a jab at "poesy," he highlighted the gendered risks of identifying as a writer at all: "I could mention other stuff like cameras, cobbey ketches, psychic phenomena, stem cars, Old Japan, Old Mexico, dames, and what not, but I am supposed to be writing on a more 'poesy' plane, what?" Aware of the gendered terrain of midcentury middlebrow, this fan sought Jones's expertise on how to navigate it; he closed his letter with a request for few pointers to a "half budding, half bumming aspirant."65 This letter and others like it show that readers were navigating not only highbrow/lowbrow distinctions but also the gender of middlebrow reading and the borders among self, book, and author.

Figure 7. James Jones, hoisting the book manuscript for his second novel Some Came Running. "The Good Life and Jim Jones," Life, February 11, 1957, 83-86.

The feminist cultural interventions Metalious made were obscured by the popular response to Peyton Place as simply a "sexy book." The fan mail Metalious received, however, suggests that readers understood and appreciated the politics of her novel, and were themselves perplexed by how the media distorted her message. Much of Metalious's fan mail, which seems to have been overwhelmingly written by women, expressed a "kinship" with the author, forged — as in James Jones's case — through a combination of her book and her public presence. "My life was so very much like yours," wrote one woman reader. "I am a nobody like you were," wrote another. "It is a shame," one Maine housewife observed, "that some interviewers cannot bring out the real person that you are and allow you to be sincerely your real self, for your reticence can be felt even over the air waves - and it is only natural for you to be on the defensive."66 A pattern of protectiveness emerges in this correspondence, indicating an awareness that the force of the media was dangerous for Metalious, if not for all women authors. Another reader described a tension between herself and the women in her community who called Peyton Place "vulgar": "HOW BADLY THEY MISSED YOUR POINT," she fairly shouts in her letter to Metalious.67 Women also wrote to Metalious because her story affirmed theirs: "I am a nobody like you were," wrote one; or I am "'an outcast' too who had an abortion, married three times and let me tell you my life would make a book." Readers spoke of a "kinship" with Metalious. As one fan wrote, "I felt a closeness -- that you are a down-to-earth person and not a snob."68 The public ostracizing of Metalious thus contrasts deeply with the sense of affiliation and close identification with the author expressed by her readers. This disconnect between public and private, a theme in Peyton Place, was also a reality in the way the media and fan responses differed. The reader correspondence indicates that the mass media was only partly successful in controlling the impact of this book, though the media did play a strong role in shaming and ultimately silencing the author.

Rank and File

James Jones and Grace Metalious met in person once. According to her biographer Emily Toth, one of Metalious's few "prerogatives of fame" was to ask her agent to arrange for her to meet James Jones for lunch at the Algonquin. While no one can say exactly what might have transpired at this meeting, we know that Metalious "greatly" admired Jones's 1951 novel.69 We know that Jones despised novels of the "Amber ilk," and that Metalious admired and emulated Forever Amber. We know that Jones arrogantly imagined his novel From Here to Eternity would "stand by itself after the movie is forgotten,"70 and that Metalious, in contrast, "doubt[ed] very much" that Peyton Place "would be remembered fifty years hence."71 On the one hand, both authors were wrong: Jones's thick novel From Here to Eternity did not outshine the better-loved film in popular memory, and Metalious's Peyton Place became a record-setting bestseller, the first prime-time soap opera, and a catchphrase that resonates to this day. On the other hand, the authors were also correct: James Jones, as the author of a macho realist war novel and winner of a literary prize, built a literary reputation that persists. And in spite of the feminist recovery work of a few scholars, Metalious is still the author no one has heard of whose first novel became the bestseller of the 20th century.72 Despite the immense cultural significance of Peyton Place, Metalious never secured even the small literary reputation that Jones still commands.73

The sales figures and enthusiastic fan response indicate that the debut novels of Jones and Metalious spoke deeply to the needs of America's postwar middlebrow readers. Jones's 1951 novel emerged in the early phases of a new postwar discourse on the middlebrow, but by the time Grace Metalious published Peyton Place, the term middlebrow had been more thoroughly concretized as one of three distinct categories of culture, and those levels had been more explicitly aligned with American class distinctions. In 1949, Russell Lynes had suggested "brows" could cross classes, but those boundaries appeared more rigid by the time his 1954 The Tastemakers appeared. In an excerpt in the New York Times, he wrote: "Highbrow, lowbrow, upper middlebrow, and lower middlebrow — the lines between them are sometimes indistinct, as the lines between upper class, lower class and middle class have always been in our traditionally fluid society. But gradually they are finding their own levels and confining themselves more and more to the company of their own kind."74 As Erica Brown argues, "the opposition between high and low culture is connected with the opposition between masculine and feminine: it is a gendered opposition ... the feminine middlebrow novel ... is neither high nor low culture, but this ... [belittling association] contributes to its exclusion."75 The construction of Jones's work as middlebrow macho helped keep him in a deep middlebrow groove for the remainder of his career. The construction of Metalious's work as sexually scandalous tilted her reputation toward the lowbrow, and she never wrote her way out of that designation: few writers could.

While to contemporary audiences, James Jones's 1951 From Here to Eternity might seem highbrow and Grace Metalious's 1956 Peyton Place might register as lowbrow, both authors were navigating the powerful force that was the midcentury middlebrow. Understanding the conditions of production and reception for each novel shows how class and gender converged in the terrain of the midcentury middlebrow. The contrasting cases of Jones and Metalious illuminate the gender double-standard that came to characterize the middlebrow at midcentury, and affirm that gender was one of the axes on which high/low cultural distinctions would continue to turn.

Anna Creadick is Associate Professor and Chair of English and American Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York. In addition to her monograph Perfectly Average: The Pursuit of Normality in Postwar America (UMass Press, 2010), she has written about Faulkner, Appalachia, whiteness, pop culture, and other subjects for Mosaic, Transformations, Appalachian Journal, Southern Literary Journal, and other venues.

References

- My gratitude to the guest editors of this cluster, the peer reviewers, and the Post45: Peer-Reviewed editors, all of whose suggestions have strengthened this essay, and some of whose language I have borrowed directly in shaping my arguments throughout.[⤒]

- I am far from the first scholar to consider gender and the middlebrow, though attention to the midcentury period in the U.S. is still somewhat lacking. Works in this vein that have been helpful to me include the following: Lisa Botshon and Meredith Goldsmith, Middlebrow Moderns: Popular American Women Writers of the 1920s (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2003); The Oprah Affect: Critical Essays on Oprah's Book Club, ed. Cecilia Konchar Farr (New York: SUNY Press, 2008); Jaime Harker, America the Middlebrow: Women's Novels, Progressivism, and Middlebrow Authorship between the Wars (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007); Nicola Humble, The Feminine Middlebrow Novel, 1920s to 1950s: Class, Domesticity, and Bohemianism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001); and Janice Radway, A Feeling for Books: The Book-of-the-Month Club, Literary Taste, and Middle-Class Desire (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1997). Joan Shelley Rubin's The Making of Middlebrow Culture (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1992) is, of course, foundational. On the "masculine middlebrow" in a British context, see The Masculine Middlebrow, 1880-1950: What Mr. Miniver Read, ed. Kate Macdonald (Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011).[⤒]

- See Anna Creadick, Perfectly Average: The Pursuit of Normality in Postwar America (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2010), 66-89.[⤒]

- Rena Corman, "Close-up of the 'Normal' Wife," New York Times Magazine, September 8, 1963, 52-69.[⤒]

- "Mezzobrows," New York Times, January 18, 1926, 20. See also Vincent Sheean, "American Drama Stirs Londoners," New York Times, July 19, 1940, 10.[⤒]

- J. Donald Adams, "Speaking of Books," New York Times Book Review, November 2, 1947, BR2.[⤒]

- David Dempsey, "In and Out of Books," New York Times Book Review, December 25, 1949, BR8.[⤒]

- Russell Lynes, "[Harper's] Reprint: 'Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow' (February 1949)." The Wilson Quarterly 1, no. 1 (1976): 146-58.[⤒]

- Russell Lynes, "Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow," Life, April 11, 1949, 99-102.[⤒]

- Russell Lynes, "Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow," Wilson Quarterly, 147, 156-57.[⤒]

- Lynes continues, "The highbrow's friend is the lowbrow. The highbrow enjoys and respects the lowbrow's art — jazz, for instance — which he is likely to call a spontaneous expression of folk culture. The lowbrow is not interested, as the middlebrow is, in preempting any of the highbrow's function." "Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow," 151-52.[⤒]

- Peter de Vries, quoted in Charles D. Rolo, "Upper Middlebrows: The Tunnel of Love," review of The Tunnel of Love, New York Times, May 23, 1954: BR5.[⤒]

- These percentages come from Richard Centers' 1949 study The Psychology of Social Classes (Princeton: Princeton University Press), cited by Walter Goldschmidt in his "Social Class in America: A Critical Review," American Anthropologist 52.4 (October-December 1950), 489.[⤒]

- The archaic root of meretricious as "relating to or characteristic of a prostitute" is worth noting. John Aldridge, discussing The Contemporary Novel in Crisis in Robert Gorham Davis, "Nothing Good," New York Times, May 1, 1966, 332.[⤒]

- On the tectonic shifts of the paperback revolution see Kenneth C. Davis' indespensible Two-Bit Culture: The Paperbacking of America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1984), as well as David Earle's work, including Re-Covering Modernism: Pulps, Paperbacks, and the Prejudice of Form (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009).[⤒]

- Elke D'hoker, "Theorizing the Middlebrow: An Interview with Nicola Humble," Interférences littéraires/Literaire interferenties 7 (November 2011): 259-265; 260.[⤒]

- For a rigorous argument for middlebrow as a coherent literary project, see Tom Perrin, The Aesthetics of Middlebrow Fiction: Popular US Novels, Modernism, and Form, 1945-75 (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2015).[⤒]

- Nicola Humble, quoted in Kate Macdonald and Christoph Singer, "Introduction: Transitions and Cultural Formations," in Transitions in Middlebrow Writing, 1880-1930, eds. Kate Macdonald and Christoph Singer (London: Palgrave MacMillan UK, 2015), 1-13; Ruth Pirsig Wood, Lolita in Peyton Place: Highbrow, Middlebrow, and Lowbrow Novels of the 1950s (New York: Routledge, 1995), 93; Seth Studer and Ichiro Takayoshi, "Franzen and the 'Open-Minded but Essentially Untrained Fiction Reader'" Post45: Peer Reviewed, July 18, 2013; Erica Brown, Comedy and the Feminine Middlebrow Novel: Elizabeth Von Arnim and Elizabeth Taylor (London and New York: Routledge, 2013); Jaime Harker, America the Middlebrow (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007).[⤒]

- It is also worth noting that for contemporary scholars, myself included, middlebrow can also mean something new: "a site in which to reposition previously neglected writers, re-examine discussion of cultural hierarchies and re-imagine the ... literary landscape." See Emma Sterry, "These are Just Romances: Love and the Single Woman in the Fiction of Rosamond Lehmann," Journal of Popular Romance Studies, March 31, 2011. [⤒]

- James Jones, From Here to Eternity (New York: Scribner's, 1951; Avon Books, 1975), 14. All subsequent references are to the Avon edition and are cited in text.[⤒]

- Grace Metalious, Peyton Place (New York: Messner, 1956; Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999), 16. All subsequent references are to the Northeastern edition and cited in text.[⤒]

- As both her biographer Emily Toth and leading scholar Ardis Cameron have argued, Grace Metalious was able to write about subjects second-wave feminists would not begin to name until after The Feminine Mystique was published, seven years later. See Toth, Inside Peyton Place: The Life of Grace Metalious (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2000) and Cameron, "Open Secrets: Rereading Peyton Place," introduction to Grace Metalious, Peyton Place (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999) vii-xxx.[⤒]

- James Jones developed a distinct vernacular writing style, the primary characteristic of which was a distain for apostrophes. I reproduce that style in quotations without further comment.[⤒]

- S.M., Letter to Jones, 13 February 1957, Cortez, Colo. James Jones Papers, Box 38 Folder 577, "Fan Mail H - M, 1951-57." Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.[⤒]

- Charles Scribner's Sons, "One of the GREAT NOVELS of our time! James Jones From Here to Eternity," advertisement, New York Times, February 25, 1951, 9.[⤒]

- Philip D. Beidler, The Good War's Greatest Hits: World War II and American Remembering (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1998), 192fn.1.[⤒]

- See Robert E. Cantwell, "James Jones: Another Eternity?" Newsweek (23 Nov. 1953), 106. See also George Garrett, James Jones (San Diego and New York: Harcourt Brace, 1984), xix, 26-27, 97.[⤒]

- As Janice Radway notes, "The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich extends over 1,245 pages. Marjorie Morningstar, Advise and Consent, The Wall, Hawaii, Stillness at Appomattox, Exodus, and The Agony and the Ecstasy are all more than 500 pages." I find it significant that so many of these bloated midcentury tomes were authored by male writers. See Radway, A Feeling For Books, 308-351, quotation p. 313-14.[⤒]

- Patricia Carbine, "Peyton Place," Look, March 18, 1958, 117.[⤒]

- "Let's Play House" [documentary]. David Halberstam's The Fifties. VHS. Vol. 3. Dir. Alex Gibney, and Susan Motamed. History Channel Documentary. A&E Home Video, 1997.[⤒]

- For a fuller discussion of the public discourse about Grace Metalious, see Anna Creadick, "The Erasure of Grace: Reconnecting Peyton Place to its Author," MOSAIC: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 42.4 (December 2009), 165-80. See also Ardis Cameron, Unbuttoning America: A Biography of Peyton Place (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015), especially Chapter 4, "The Other Side of Writing," and Chapter 5, "The Gendered Eye."[⤒]

- "You live in a town, and there are patterns," Metalious explained. "The minute you deviate from the pattern, you're a freak. I wrote a book, and that makes me a freak. They don't like that." The quote appeared in an AP story by Joseph Kamin, reprinted in the Laconia [NH] Evening Citizen, August 29, 1956. Collected in the Laconia, NH, Public Library file on Metalious.[⤒]

- Julian Messner, Inc. "This is the explosive book..." Peyton Place advertisement, New York Times, September 23, 1956, 23. See Evan Brier, A Novel Marketplace: Mass Culture, the Book Trade, and Postwar American Fiction (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011) for a discussion of Peyton Place as a culmination of early 20th century publishing and marketing practices already well underway.[⤒]

- A recent e-book republication of From Here to Eternity restores some scenes of "censored gay sex" omitted from Jones's original, although it was perceptible enough in the original, as I discuss in my chapter "From Queer to Eternity" in Perfectly Average, 90-117. See Benedicte Page, "Censored Gay Sex in From Here to Eternity Restored for New Edition," The Guardian, April 5, 2011.[⤒]

- "Let's Play House" [documentary]. David Halberstam's The Fifties. VHS. Vol. 3. Dir. Alex Gibney, and Susan Motamed. History Channel Documentary. A&E Home Video, 1997.[⤒]

- Caldwell's God's Little Acre (1933) hints at father/daughter-in-law incest, and Tobacco Road (1932) hints at father/daughter incest. Caldwell's reputation famously shifted from more literary/highbrow responses to his work in the 1930s to a largely lowbrow/pulp view of those same works when they became paperback bestsellers in the 1940s and '50s. See Stanley W. Lindberg, "The Legacy of Erskine Caldwell," The Georgia Review 66.3 (Fall 2012), 495-99. Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita was published in Paris by Olympia Press in 1955, but an American edition would not appear until 1958. A typical moment of reflection from the stepfather-narrator Humbert Humbert indicates the absurdity of his dilemma as kidnapper-rapist of the girl Dolores Haze (Lolita): "Query: is the stepfather of a gaspingly adorable pubescent pet, a stepfather of only one month's standing, a neurotic widower of mature years and small but independent means, with the parapets of Europe, a divorce and a few madhouses behind him, is he to be considered a relative, and thus a natural guardian?" See Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita (New York: Vintage, 1997), 172.[⤒]

- Quoted in James Dodson, "Pandora In Blue Jeans." Yankee, September 1990: 92-97, 132-137; 134.[⤒]

- Hal Boyle, "Grace Unfolds to Hal Boyle Hazard of Husband Losing Job; Hal Calls Peyton Place a Tobacco Road with a Yankee Accent," The Laconia [NH] Evening Citizen, August 29, 1956: 1.[⤒]

- David Dempsey, "Tough and Tormented: This Was the Army to Mr. Jones," review of From Here to Eternity, New York Times Book Review, February 25, 1951, 5. Carlos Baker, "Small Town Peep Show," review of Peyton Place by Grace Metalious, New York Times Book Review, VII, September 23, 1956, 4.[⤒]

- Brier, A Novel Marketplace, 125.[⤒]

- "The Good Life and Jim Jones," Life, February 11, 1957, 83-86.[⤒]

- Patricia Carbine, "Peyton Place," Look, March 18, 1958, 110. See also the three-part series authored by Grace Metalious, "All About Me and Peyton Place," American Weekly, May 18 ; June 1; June 8, 1958.[⤒]

- Prewitt also imagines that "The next time he ran into Jack Malloy he would be able to talk back instead of just listen." Malloy is Jones's "philosopher-criminal" character, who, Tom Perrin argues, occupies the "moral center" of the novel. Perrin characterizes Malloy's pontifications as a classically middlebrow literary mode he terms "bluster," and in this scene of masculine self-improvement, Prewitt becomes a blusterer-in-training. See Perrin's "Oh Blustering: Dwight Macdonald, Modernism, and The New Yorker" in Fiona Green, ed. Writing for The New Yorker: Critical Essays on an American Periodical (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015): 228-248.[⤒]

- Robert E. Cantwell, "James Jones: Another Eternity?" Newsweek, November 23, 1953, 106.[⤒]

- John W. Aldridge, "Speaking of Books," review of From Here to Eternity, New York Times, September 2, 1951, 2. David Dempsey, "Tough and Tormented: This Was the Army to Mr. Jones," review of From Here to Eternity, New York Times Book Review, February 25, 1951, 5.[⤒]

- Dempsey, "Tough and Tormented," 5. Orville Prescott, "Books of the Times," New York Times, February 26, 1951, 21.[⤒]

- James Jones, Letter to Burroughs Mitchell, 3 October 1950, quoted in To Reach Eternity: The Letters of James Jones, ed. George Hendrick (New York: Random House, 1984), 173-74. Norman Mailer had famously lost this fight in The Naked and the Dead, using "fug" as a substitute to get past the censors.[⤒]

- Orville Prescott's concluding lines in his New York Times review: "when [Jones] describes the sadistic tortures inflicted in the punishment 'stockade' he leaves his sickened and enraged readers wondering how much American Army practices duplicate those of the totalitarian nations." "Books of the Times," New York Times Book Review, February 26, 1951, 21.[⤒]

- Carlos Baker, "Small Town Peep Show," review of Peyton Place by Grace Metalious, New York Times Book Review, VII, September 23, 1956, 4.[⤒]

- Joyce Davidson, television interview with Grace Metalious, quoted in "Let's Play House," David Halberstam's The Fifties, vol. 3, dir. Alex Gibney (History Channel Documentary: A&E Home Video, 1997).[⤒]

- David Dempsey, "Tough and Tormented, This was the Army to Mr. Jones," review of From Here to Eternity, New York Times Book Review, February 25, 1951: 55.[⤒]

- Quoted in Toth, Inside Peyton Place, 145.[⤒]

- Margaret Latrobe, Laconia Evening Citizen, October 10, 1956. Collected in the Laconia, NH, Public Library file on Metalious.[⤒]

- Ardis Cameron, "Blockbuster Feminism: Peyton Place and the Uses of Scandal," in Must Read: Rediscovering American Bestsellers (London: Continuum, 2012), 266-67, 263.[⤒]

- See Cameron, "Open Secrets," viii, xxi, xxviin6. Metalious died, her estate insolvent, before the television series premiered.[⤒]

- Amy Blair shows how manuals like women's guidebooks for home decor as well as columns in women's magazines "instructed their middlebrow readers in highbrow aesthetics" in the early decades of the twentieth century. See her Reading Up: Middle-Class Readers and the Culture of Success in the Early Twentieth-Century United States (Philadephia: Temple University Press, 2012), 165.[⤒]

- Quoted in Otto Friedrich, "Farewell to Peyton Place," Esquire, December 1971, 160.[⤒]

- Ardis Cameron relays a reader's recollection of walking in on her mother and her mother's best friend "whispering in the kitchen. As soon as I entered, they whipped a book into a bag, but they were too slow. I had caught my mother reading Peyton Place, a book banned by our town library!" See Cameron, "Open Secrets," viii.[⤒]

- See Dwight Macdonald, "Masscult and Midcult," reprinted in Macdonald, Against the American Grain: Essays on the Effects of Mass Culture (New York: Random House, 1962), 3-75, 73. [⤒]

- J.D., Letter to Jones, 3 December 1952, Honolulu, HI; S.J.B., Letter to Jones, Philadelphia, October 21, 1953. "Fan Mail A - G, 1951-57," Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.[⤒]

- M.L.G., Letter to Jones, 13 February 1957, Coral Gables, FL. James Jones Papers, Box 38 Folder 576, "Fan Mail A - G, 1951-57." Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.[⤒]

- F.D. Letter to Jones, 15 June 1956, Champaign, Ill. James Jones Papers, Box 38 Folder 576, "Fan Mail A - G, 1951-57." Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. [⤒]

- H.E.C., Letter to Jones, 22 March 1953, Liberal, KS; S.J.B., Letter to Jones, Philadelphia, 21 October 1953. "Fan Mail A - G, 1951-57." Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.[⤒]

- M.S., Letter to Jones, 12 March 1957, Charleston, SC. James Jones Papers, Box 38 Folder 577, "Fan Mail H - M, 1951-57." Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.[⤒]

- V.M.G, Letter to Jones, 15 April 1957, San Francisco, Calif. James Jones Papers, Box 38 Folder 576, "Fan Mail A - G, 1951-57." Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.[⤒]

- Cameron, Unbuttoning America, 164-66. The excavation of fan mail received by Metalious has been the most recent contribution of Metalious scholar Ardis Cameron. See her 2012 essay "Blockbuster Feminism" as well as her 2015 book-length study Unbuttoning America, especially Chapter Eight, "Excitable Fictions.[⤒]

- Quoted in Cameron, "Blockbuster Feminism," 269.[⤒]

- Quoted in Cameron, Unbuttoning America, 165-166.[⤒]

- Toth, Inside Peyton Place, 151.[⤒]

- James Jones, letter to Burroughs Mitchell, 2 December 1950, quoted in Hendrick, To Reach Eternity, 178.[⤒]

- Joyce Davidson, television interview with Grace Metalious, quoted in "Let's Play House," David Halberstam's The Fifties, vol. 3, dir. Alex Gibney (History Channel Documentary: A&E Home Video, 1997). [⤒]

- Peyton Place remained the all-time fiction bestseller until the early 1970s, with the release of The Godfather and the advent of new cross-marketing publishing strategies that led to phenomenally higher sales figures. Grace Metalious struggled to produce three more critically panned novels before drinking herself to death in 1964, insolvent, at age 39. She neither lived to see nor realized any profit from the infamous television iteration of her blockbuster. See Cameron, "Open Secrets," xiii, xxi, xxvii n6.[⤒]

- There is a James Jones Society which sponsors a James Jones first-novel award, and his books are still in print and being made into films. Contemporary writers have lauded From Here to Eternity, from Joan Didion in The White Album to James Ellroy, who wrote: "From Here to Eternity is a great American novel. It remains incandescent after 58 years." (See "Damned 'From Here to Eternity' You Must Read This: Writers Recommend their All-Time Favorite Books" npr.org, July 15, 2011). Jones's novel is also on the Modern Library's 100 Best Novels list. While Metalious has her devotees, and scholarly attention to Peyton Place has increased since its 1999 republication in an academic edition, her novel is still widely considered a potboiler, and she certainly does not have a "Society." [⤒]

- Extract from The Tastemakers by Russell Lynes, New York Times Book Review, October 17, 1954: BR2. Emphasis added.[⤒]

- Brown, Comedy and the Feminine Middlebrow Novel, 116.[⤒]