Emoji Dick and the Eponymous Whale, An Essay in Four Parts

I.

"This whole book is but a draught—nay, but the draught of a draught. Oh, Time, Strength, Cash, and Patience!" (Moby-Dick 193)

A book. Its author, Herman Melville (1819-1891). Its title, Emoji Dick; or, The Whale (2010), only instead of the words "the whale," picture an enlarged and therefore pixilated emoji — the spouting whale — a version of what might appear in a web browser or on an Apple device but not a version that can yet appear easily in the word processing software I used to write these words, or on an Android device, where it would look a little different. Emoji Dick is a book that in a real sense cannot be fully named — the name of which cannot be pronounced — since an accurate rendering of its title includes an image. Cataloguers at the Library of Congress settled, as I have, on the title Emoji Dick, or, The Whale, only with a slight change in punctuation, replacing the author's semicolon with a comma to conform to current book-titling practice, which typically separates titles and subtitles with either a comma or a colon, not a semicolon. No big deal. Punctuation is "accidental" not "substantive," a scholarly editor might reassure you. (It is in some likelihood an artifact of publication conventions not authorial intentions.) But a name? That's different. The title of this extended essay is "Emoji Dick and the Eponymous Whale" because names are important, and one of the things I'd like to do is follow the name of this book into Melville's novel, originally entitled, as it happens, Moby-Dick; or The Whale.1 I offer an extended description of Emoji Dick because I think it is such a pleasurable, perverse, and provocative object. More particularly, Emoji Dick offers a ludic contact zone between human intelligence and algorithmic processing, between text and image under the sign of computation, as well as between literature and whatever the fate of the literary may be in an ever more digitally mediated and data-described world.2

The cover of Emoji Dick

To begin with, a few details: The cover of Emoji Dick alerts us that it was "edited and compiled by Fred Benenson" and "translated by Amazon Mechanical Turk." Front matter includes an "About This Book" page [vii], which explains further that "Each of the book's approximately 10,000 sentences" was rendered into emoji "three times by a Amazon Mechanical Turk worker," and then these "results" were "voted" upon by other Mechanical Turk workers "and the most popular version of each sentence" was selected and used in the book. We learn that in all "over eight hundred people spent approximately 3,795,980 seconds working to create this book" and that workers earned "five cents per translation and two cents per vote." The money needed was raised on the crowd-funding platform Kickstarter.com. It took 30 days and contributions from 83 people to afford the labor and to cover a small initial printing of the book through the on-demand, self-publication site Lulu.com.

Though a good bit about the creation of Emoji Dick is not covered in this brief explanation, the confluence of "approximately 10,000 sentences," "over eight hundred people," and "approximately 3,795,980 seconds" points toward a book, a novel, an American classic, reimagined, managed, and executed as piecework: work for hire paid by the piece. Amazon's Mechanical Turk is a crowdsourcing platform named after a famous 18th-century hoax, a chess playing "automaton" powered by a hidden person. The Mechanical Turk platform coordinates a global workforce for U.S.-based employers who request and remunerate batches of tiny, discrete jobs that Amazon calls Human Intelligence Tasks (HITs). These tasks as a rule cannot be adequately or easily automated. Like tagging images, transcribing song lyrics, and decoding CAPTCHAs, they require human intelligence.3

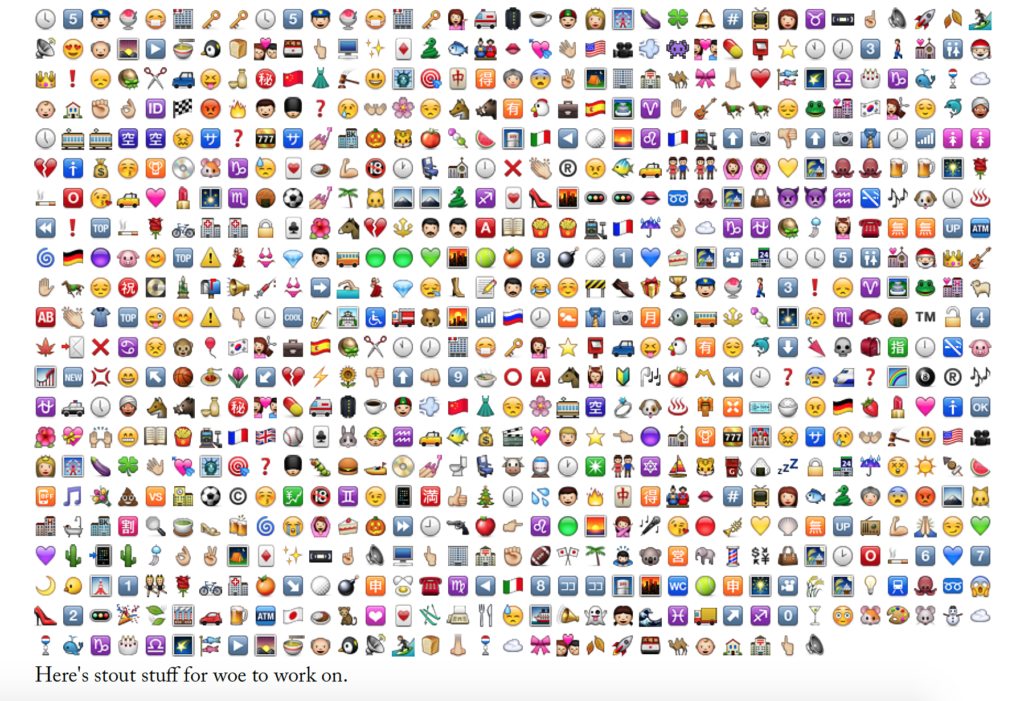

While the nineteenth-century printers who originally produced Melville's novel would also have imagined Moby-Dick as piecework, the labor in question would have been much different. Compositors would have set individual pieces of type — nineteenth-century compositors were typically paid per thousand ems set — working from individual sheets of manuscript copy. (An em is a unit that varies with the size of the typeface being set, since larger faces can be set more quickly than smaller ones.) Melville's wife served as his copyist, we think, so the manuscript — now lost — would have been in Lizzie's handwriting with her man Herman's edits and corrections: Hello Bartleby?4 By contrast, Benenson's workers — familiarly "Turkers" — encountered the novel not as sheets or pages of copy and ems to typeset but rather as individual sentences for so-called translation and voting. To avail himself of the Mechanical Turk platform, Benenson had to chop the novel into HITs, which meant pulling it apart into sentences. Readers of Emoji Dick encounter the novel that way too, because this "translation" is interlinear: each sentence of Melville's text is preceded by its counterpart in emoji. Or, to put that another way, each sentence of Emoji Dick appears as a sequence of emoji captioned or subtitled by Melville's words.

"All great texts contain their potential translations between the lines," Walter Benjamin once remarked, which suggests that interlinearity is the consummate page layout for aspiring translations.5 Here the layout accedes as much to the logic of producing Emoji Dick as to the greatness of Moby-Dick or its putative translatability, since readers encounter the novel divided into the same increments that Benenson's Turkers did. The novel reimagined as piecework looks and reads that way too.

The nineteenth-century printers of Melville's novel would have had trade practices in common, shared knowledge of the printing house, its traditions, tools, and hierarchy of tasks, as well as relevant anxieties about the rising tide of mechanization and decline in the apprenticeship system. By contrast Amazon's Mechanical Turkers form a "crowd" (as in crowd source) not a trade, and it is all but impossible to imagine them as a class. They are alike in their platform-based participation in work for hire, doing the bidding of American "requesters" good and bad, yet any solidarity they might accrue is only the potential result of additional participation in Turk-related message boards, where they can share tips and rate requesters or HITs. In comparing this crowd with the collaborative crowd responsible for Wikipedia, for instance, we tend to imagine a precarious global workforce alienated and exploited as they scramble for pennies meted out by savvy "Gig-economy" employers in the U.S. who are seeking the "on-demand, scalable workforce" promised by Amazon. But it's hard to know anything for sure. Turking, unlike printing, is done under wraps. Like the ingenious Van Kempelen hiding a person inside his chess-playing machine in the eighteenth century, Amazon does not disclose the inner workings of its Mechanical Turk.

For his part, Benenson merrily salutes the Turkers responsible for Emoji Dick in his Acknowledgements, where he gives a long list of "all the individual Amazon Turk workers whose effort and clicks are the foundation of the project" (724). Participants on the Amazon Mechanical Turk platform are always anonymous, though, so the list offers only platform-specific identifiers, like A106Q3N3OECN73 and A108WVBRT2DT4K. It's safe to say that no nineteenth-century novel acknowledges the individual printing house employees behind its production, even pseudonymously. So what we encounter in Emoji Dick is both a radically new, network-based phenomenon and a good reminder that books have always been the results of distributed labor, the nexus of multiple and unsung human and nonhuman agencies, all of the tasks done by workers and all of the work done by the material components and conditions of their labor.

College English majors rarely think in such crass, material terms. They tend to direct their attention to an ideal construct called the literary work, not the manufactured text through which that work is so generatively discerned, even as habits of reference ("Turn to page 63," e.g.) and the demands of commerce ("That will be $11.95, please," e.g.) natter at this high-mindedness. Still, there is a sense in which readers have long been used to thinking about books both as networked entities and in pieces. For centuries humanists and scholars have used books by culling excerpts out of them, whether for published compendia, commonplace books, or researchers' note cards. Once culled and sorted or indexed, excerpts establish productive new connections among books. Today things seem different. Google serves us snippets based upon our search strings and its giant digital corpus, which underwrites a new "bibliographical imagination" oriented toward "everything" (that is, everything searchable). Earlier generations collected excerpts laboriously "by hand," based upon individual reading experiences that were subjectively enabled by — as well as enabling of — a collective bibliographical imagination, an awareness of the world of books as such, its constitutive agencies — authors, publishers, readers, editions — and intertextual connectivities.6 Melville's novel, case in point, opens with a brief preliminary section entitled "Etymology" ("Supplied by a Late Consumptive Usher to a Grammar School") and a longer section entitled "Extracts" ("Supplied by a Sub-Sub Librarian"), both containing excerpts from earlier authors. How long and how widely Melville must have read in order to harvest — to read, select, and transcribe — his authorities on whales: Genesis, Jonah, Pliny, Plutarch, Rabelais, Shakespeare, Captain Cook, Thomas Jefferson, Charles Darwin, and so many more. Emoji Dick omits the etymology and extracts; it gets right down to business with Chapter One, sentence one, "Call me Ishmael." Breaking the novel into sentences arrives at a scale that is simultaneously suitable for Turking and reminiscent of texts and tweets, the diminutive semantic habitats — Are they formats? Or genres? — to which emoji most assuredly belong.

But before we get to emoji, just a few more details: like the standard scholarly edition of Moby-Dick — the 1,043-page Northwestern-Newberry edition published in 1988 — Emoji Dick did not involve any act of transcribing from earlier text. The Northwestern-Newberry editors wanted to use the first impression of the first American edition of Moby-Dick as their copytext — the core version they examined in relation to others — so instead of retyping the whole book — it's a big one, after all — the copy they marked and sent to Northwestern University Press was a xerographic print made from a microfilm of Harvard University's copy, identified as *AC85M4977.851ma(D).7 (Library books, like Turkers, go by alphanumeric code names.) Benenson likewise was not going to keyboard all of Moby-Dick sentence by sentence. A slightly garbled note on Emoji Dick's copyright page explains that the version used is from Project Gutenberg, the by-now-venerable, public-spirited repository of free e-books.8 Project Gutenberg had its origins in 1971 and is committed to editions presented in ASCII, that is, as .txt files.9 The Project long eschewed textual markup strategies, advocating in favor of plain vanilla literary content.10 It was an advocacy of supposedly un- or non-formatting that drove scholarly editors crazy, and that today reads as a throwback to some small, flat earth. As Finn Brunton explains the look of early networking, it was "one color (usually amber or green) and ninety-five printable characters — numbers, the English alphabet in uppercase and lowercase, punctuation, and a space."11 A textual interface: small, constrained, and parochial.

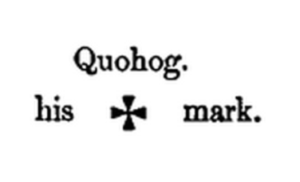

The text used by Benenson, it may be gleaned, was produced in 2001 by combining one electronic text from the now-defunct ERIS project at Virginia Tech (happily preserved at the University of Adelaide) and another from Project Gutenberg's own archives. It was proofread against a hardcopy, edition unspecified. An "Original Transcriber's Note" — original to the full text produced for Project Gutenberg, or to one of its two components — indicates further, "In chapters 24, 89, and 90, we substituted a capital L for the symbol for the British pound, a unit of currency."12 This is because ASCII characters do not include the symbol for a British pound sterling. In order to include the £ character, Project Gutenberg's transcribers had to figure out a workaround. They could have paused to insert a placeholder of some kind. They could even have interrupted their character string to insert an image file, a little picture of £. They decided to use the closest character encoding available in the ASCII standard: L. That Emoji Dick retains the capital L instead of a pound symbol is a modest "tell," an incidental clue that Benenson downloaded Project Gutenberg's text file, wrote and ran a script to divide it into sentences, and presented them for Turkers to work on, who sent them back for assembly into a book.13 None of this labor was trivial, but all of it was automated. We could call it coding, programming, or maybe skilled batchwork. Only the Turkers worked piece by piece, selecting individual characters from the emoji character set to accompany Melville's text in English. Following the ASCII version it incorporates, the English text of Emoji Dick contains minimal formatting. So there are no centered cenotaphs in display type in Chapter 7, for instance, and no Maltese cross for Queequeg's signature in Chapter 18. But in presenting Melville's text, for whatever reason (Thank you Microsoft Word?) the plain vanilla look of ASCII has been replaced by painfully workaday Times New Roman.

If presenting a text in ASCII leaves relatively few choices, letterpress printing produces them in abundance. Indeed, we might profitably imagine for one moment the nineteenth-century compositor paid by Harper & Brothers to set Melville's Chapter 18 in type. He reaches an awkward moment. The harpooner Queequeg must sign the ship's papers to join the Pequod on its voyage, but Queequeg is illiterate. That's not the awkwardness. As Melville's narrator Ishmael explains, Queequeg "looked no ways abashed; but taking the offered pen, copied upon the paper, in the proper place, an exact counterpart of a queer round figure which was tattooed upon his arm" (100). The novel continues; Ishmael quotes the ship's papers, showing both a representation of Queequeg's name as it has been comically if xenophobically misrepresented by the officer signing him in — Quohog — and a representation of the "queer round figure" that Queequeg "copied" from his arm. Here our compositor hesitates. We have no way of knowing how the queer round figure looked on the manuscript copy before him, because the manuscript does not survive, yet however it looks he must somehow render it into type. He must leave the type cases in front of him, upper and lower, with their font of commonly used letters, punctuation, and spacing, to find something like "a queer round figure" amid the specialized type sorts nearby. Like someone using emoji, he must switch from one character set to another, waving away the usual alphanumeric signs in favor of something less familiar, less linguistic.

What is queer to Ishmael in this instance — because it is not legible or intelligible, because it de-familiarizes the signature as bodily trace, or because it relates to another man's skin — is awkward for the compositor because it is not easily set or accurately printable by type. Our compositor seizes upon the (admittedly not very round) Maltese cross, and the job is done. It's a delightfully "phat" or "fat" job too, in printers' jargon, because centering "Quohog" and Queequeg's mark on the page leaves open a lot of blank space that can be set quickly — lots and lots of ems — before proceeding on with the rest of the chapter. Our imaginary compositor is happy, while clearly Melville's novel thematizes questions — I would go so far as to call them pressing grammatological questions — which its own production and reproduction in print, including in emoji, help to open and adumbrate. In this instance we might consider Melville as the leading edge of what Christopher Bush has termed "ideographic modernism," referring to the ways that the Orientalized Other has "served [in the West] as a means of thinking and writing about aspects of language whose critical formulation largely had to await the advent of 'theory.'"14

What is queer to Ishmael in this instance — because it is not legible or intelligible, because it de-familiarizes the signature as bodily trace, or because it relates to another man's skin — is awkward for the compositor because it is not easily set or accurately printable by type. Our compositor seizes upon the (admittedly not very round) Maltese cross, and the job is done. It's a delightfully "phat" or "fat" job too, in printers' jargon, because centering "Quohog" and Queequeg's mark on the page leaves open a lot of blank space that can be set quickly — lots and lots of ems — before proceeding on with the rest of the chapter. Our imaginary compositor is happy, while clearly Melville's novel thematizes questions — I would go so far as to call them pressing grammatological questions — which its own production and reproduction in print, including in emoji, help to open and adumbrate. In this instance we might consider Melville as the leading edge of what Christopher Bush has termed "ideographic modernism," referring to the ways that the Orientalized Other has "served [in the West] as a means of thinking and writing about aspects of language whose critical formulation largely had to await the advent of 'theory.'"14

Let me stress that these genetic details matter. Parsing narratives of textual production and reproduction not only serves to illuminate the book as a nexus of agencies, it can also act as a corrective to the cavalier ways in which popular discourse today distinguishes "print" from "digital" text in reference primarily and myopically to the mass market codex and the handheld screen. Neither print nor digital textuality is a simple or monolithic formation, and the complex textual conditions of the present moment, electronic and not, remain radically underexamined.15 Emoji Dick is the result of both close attention to detail and more distant algorithmic operations. Comprised simultaneously of piecework and batches of processing, it is a creative work of incremental decision-making and of data pours. (Shifts in scale exist everywhere: Melville's first edition was painstakingly set in type and then — a different sort of pour — stereotyped for printing and reprinting from metal plates.) Crowd-funded and crowd-sourced, Emoji Dick inhabits what Rita Raley calls our new "socio-technical milieu" in which "we can no longer be certain about the distinction between a human-produced text and textual expressions that have been algorithmically mediated."16 Where, if anywhere, is the line between writing and machine-generated character strings? "The crowd" of current fame is an aggregate of networked subjects tuned variously to the exploits and exploitations of dot-com capitalism. And here the crowd variously reworks the old-fashioned populism of Project Gutenberg into the slick neoliberal logic of Lulu.com, the former conceived (in 1971) in the interests of democratic access, the latter (2002) in terms of individual empowerment through self-publication.17

Digital from stem to stern, surely Emoji Dick deserves for all of this to be called an electronic book, even if I own it as a hefty codex. No, even e-books today get International Standard Book Numbers or ISBNs, but a thorough inspection of Emoji Dick doesn't turn up one of those.18 It's a non-standard book-object; perhaps that's the best encapsulation for now. Laser-printed in full color, Emoji Dick costs $200. Though increasingly well known, it's not much of a moneymaker. I figure that Kickstarter, Amazon, Lulu, Benenson, and the Turkers are all in the black, but modestly so.19 My copy makes a weird cracking sound when I open it, as if it's about to break in two. (To be fair, my Northwestern-Newberry paperback Moby-Dick succumbed long ago.)

One thing Emoji Dick most certainly is not — pace Benenson — is a translation, since emoji are pictorial not linguistic. Pictographs are not real writing. They lack the flexibility and range of written language, a lack that helps account for the constant pressure to add more and more emoji to the character set. Rare are the communications — within Emoji Dick or abroad in the world — in which emoji have syntactic utility. Scroll through the hundreds of emoji there are to choose from to date, and you might come up with some interesting observations about the differences between novels and text messages or between literary and non-literary discourse. (You may consider as well the ways that writing on smartphones seems to veer away from the habitual conditions of inscription and thereby verge on more oral forms of communication.) Apple divides emoji into People, Nature, Food & Drink, Celebration, Activity, Travel & Places, and Objects & Symbols, and it would be difficult to reconcile any novel or literary corpus with such a classification scheme.20 The telephone emoji works splendidly for the "Call" in "Call me Ishmael," but how can emoji work practically or consistently as adverbs, pronouns, articles, or adjectives? How can they convey the conditional or the interrogative; how can they suggest negation, subordination, or other grammatical relations? Like all pictographs and pictographic systems, emoji beg the question of universal language without being language at all.

Even the most casual browsing through the pages of Emoji Dick reveals the delightful absurdity of Benenson's project and the peculiarity of its execution. At first glance, the Turkers' division of labor seems to have proven grievously disabling, since even the correspondence of the words "whale" or "Moby Dick" to the spouting whale emoji is underdetermined and radically inconsistent, while repeated uses of the same word — such as the exclamation "Oh!" or the name "Pip" — have hilariously different "translations" within the course of even a few pages. Upon closer examination, occasional correspondences may be found between Melville's text and Benenson's emoji, but randomness predominates, so much so that one wonders whether Benenson's Turkers weren't wantonly inattentive, generally non-Anglophone, or especially ingenious programmers able to automate selection of emoji without reference to Melville's words. Needless to say, the richness and density of Melville's prose, the supreme breadth of his diction and abundance of verbiage, cannot have a counterpart in images, even where judiciously selected. Take the extreme case, for instance, a fugue-like sentence at the beginning of Chapter 42, "The Whiteness of the Whale": it runs for 467 words and is rendered as nine emoji, utterly nonsensical (253). Elsewhere there is a seven-word sentence translated as 764 emoji (529). Emoji Dick is a joke, a big one and timely.

This is not to denigrate Benenson's project. Because it cannot be the translation that it says it is, Emoji Dick works as an outsized reminder that translating is a deeply problematic endeavor, as necessary and as enriching as it may also be. This is especially the case with literature. After all, "What does a literary work 'say'?" Benjamin asks, "What does it communicate?" Because literature does more than merely communicate information, any translation that sets out cellphone-like to "perform a transmitting function" is doomed to fail.21 Translations owe their existence to the literary works they serve, and yet the best of them also renew and transform the originals, precisely as they exceed a mathematical, Shannon-Weaver-like model of communication, in which an information signal gets transmitted through a channel to a receiver. The mutual foreignness of languages — pace Google Translate — is more than just noise in the system, a point that is only most obviously the case for literature. The word emoji is itself an interesting case in point, as I will touch upon below.

Emoji Dick may not be a translation in the most literal sense, but the curious semiotic functions of emoji do help it to inhabit some of the dilemmas of translation. For if emoji are pictorial, not linguistic, they nonetheless work like language in several respects, even if what they communicate remains pretty fuzzy, or warm and fuzzy. Benenson — something of a partisan — has written a book entitled How to Speak Emoji; a company called Adams Media is hawking an emoji-to-English dictionary; and many users readily testify that they are making themselves understood across social networks and within coteries, despite a pictographic repertoire tilted toward facial expressions, hand gestures, and what look mostly like things/nouns. (How often do we really use the word "sushi" or "panda" or "sailboat" after all?) A few linguists have even begun to investigate the ways that emoji are being used, and amateur linguists among us can take a crack at this question too by pondering Matthew Rothenberg's emojitracker.com, which offers a real-time look at the ways individual emoji are being used across the Twittersphere.22 The emojitracker allows us to gauge how different emoji are being used differently across cultures and in various linguistic contexts as those contexts have each been adapted to Twitter.

Further resemblance between emoji and writing arises from the ways emoji rely upon graphical linguistic techniques (character selection, if not quite typing on keyboards) and inhabit the graphical linguistic sphere, especially in their relation to punctuation and emoticons. Emoji are widely understood to be an extension of emoticons (and Japanese kaomoji), and so they build upon the increasingly capacious utility of punctuation marks and other non-phonetic operators — like the hashtag — we now think of as related to punctuation.23 Theodor Adorno once remarked that punctuation is where language most "resemble[s] music." He was thinking of tempo, certainly, but also of tone.24 Emoticons and now emoji greedily inhabit the tonal register, less as signs with semantic value and more as phatic expressions, communicating the in-commonness of communication. Emoji in this sense hold the channel open as signifiers of "affect, emotion, or sociality," marking the existence of senders and recipients as subjects within a shared exchange, enabling the expression of affective states amid otherwise linguistic communications.25 Emoji Dick opens the line, then, not so we can hear from Herman Melville exactly, but so we can feel good knowing that he's still there.

II.

"If that double-bolted land, Japan, is ever to become hospitable, it is the whale-ship alone to whom the credit will be due; for already she is on the threshold" (110).

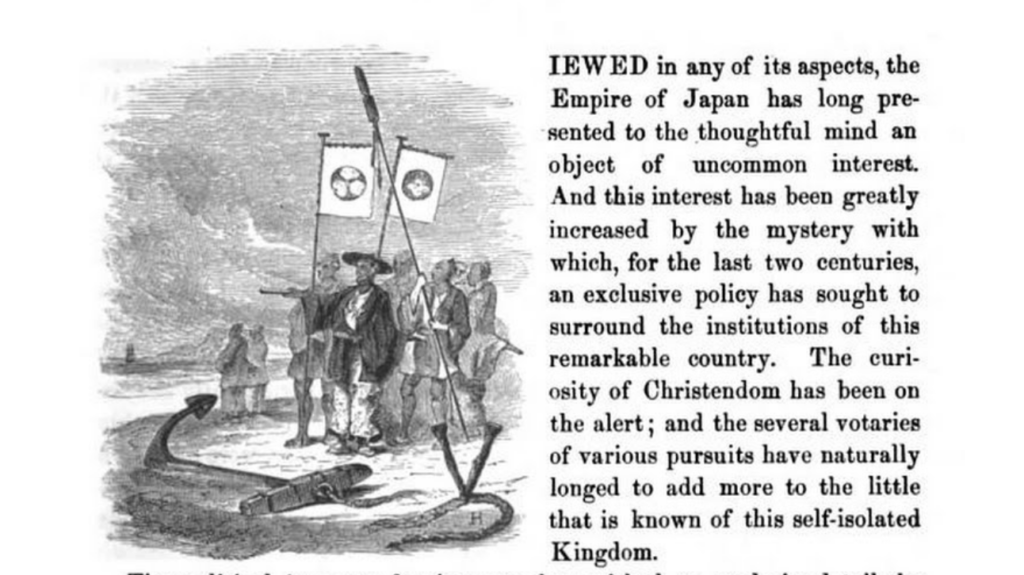

The year after Moby-Dick was published, Commodore Perry arrived to "open" Japan to the West, or so U.S. history has always flattered itself. When Perry published the official account of his mission, his Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan (1856) opened with an introductory description of the "self-isolated" island kingdom, including its language.26 Perry reports that "the idiographic cypher of the Chinese" was introduced into Japan in A.D. 290, but that Japan also has "an alphabet, or rather a syllabarium" of its own. He then uses contemporary comparative philology to suggest the non-Chinese origins of the Japanese people, at one point approving Japanese pronunciation in contrast to the "confused sing-song monotone" of Chinese, which is so "unpleasant to the ear."27 When the printers employed by D. Appleton & Company in New York City set Perry's lavish Narrative in type, they used specially made engravings as initial capitals to begin the introduction and subsequent chapters. Thus the introduction, which opens "VIEWED in any of its aspects, . . ." really begins with a little picture. It's a scene on a beach with a small delegation of Japanese men in the middle distance. In the foreground lies an anchor and cable half-buried in the sand. Rising oddly from the cable is a large capital letter V (and beneath it a smaller letter H, the engraver's initial). So the letterpress type of Perry's Narrative — and the encoded plain text version captured by scanners for Google Books — actually begins "IEWED in any of its aspects, . . ." Readers don't have to distinguish the V as an image and the IEWED as text, but D. Appleton certainly did, and so does Google.

It's an incidental example — a matter of producing, reproducing, and encoding a few characters, printing and later digitizing a book — but it's one that points squarely to the zone of signification where emoji presently abide and thus where any account of Emoji Dick must take us. Like the image of capital V standing on that Japanese beach, emoji exist at an arbitrary junction of text and image at the same time that they negotiate the juncture and juxtaposition of East and West.

Emoji originated in Japan, where the neologism emoji carries the sense of picture + writing + character to mean pictograph. These pictographs carry cultural weight as exports/imports, reversing Commodore Perry's trajectory while tagging the intensity of Japanese culture industries in their production of popular, even addictive cultural forms with global purchase. Think of Godzilla, Manga, or Pokémon. The Japanese telecommunication industry introduced emoji in the late 1990s to the delight of many of its customers, although each carrier had its own underlying technology, so texting emoji to someone with a different service provider wasn't a sure thing. Today mojibake — writing + character + transform — is the word used widely for garbled transmissions that are the result of sending invalid or unsupported characters. You will probably have seen garbled transmissions appear partly as a string of narrow rectangles, sometimes called "tofu," one form of .notdef glyph ("notdef" for "not defined"), mojibake that appears when someone sends you characters or font that your operating system or application doesn't recognize.28

The popular uptake of emoji in East Asia, the spread of smartphones everywhere, and the multinational exertions of Google and Apple all eventually created pressure for standardization, to the point that the Unicode Consortium agreed to support encoding standards for emoji in 2007.29 (More on Unicode below.) Apple added emoji to its iPhone, also in 2007, although the cartoon characters had to be unlocked with a Japanese-language app on North American phones until 2011, indicating what a canny early adopter Fred Benenson must have been, since Emoji Dick appeared in 2010. Popular attention in the West has surged in recent years, and emoji now proliferate in text messages and across social media platforms like Twitter. Knock-off "stickers" populate Facebook and other social networks, part of the way that all of these platforms increasingly encourage "users to classify themselves emotionally," for fun as well as for algorithmic analysis by the platforms and therefore for potential profit by the advertisers who pay them.30 As one journalist declared in a New York Magazine cover story of 2014, emoji "are a small invasive cartoon army of faces and vehicles and flags and food and symbols trying to topple the millennia-long reign of words."31 The magazine called on Fred Benenson, incidentally, to turn those words into emoji: mobile phone with input arrow, cartoon family, VS, pen, hourglass, old person, notebook. (He's much better at this than his Turkers were.)

This battle is joined by a billion tapping thumbs, but the war between words and images has been long already. The whole history of culture, W.J.T. Mitchell notes, "is in part the story of a protracted struggle for dominance between pictorial and linguistic signs," in which words have always seemed to win the higher ground.32 We glimpse this struggle in ancient prohibitions against graven images, as well as in modernity, amid successive spasms of moral panic around the supposed seductions of chromos, cinema, comic books, television, and video games. Most famously, the contest between word and image in the West has been understood in the contrast between poetry and painting: Gotthold Lessing's Romantic aesthetics had it that "time is the province of the poet just as space is that of the painter."33 Writing has to be apprehended in sequence, whereas visual images flash upon the mind's eye all at once. It is an important distinction now apparently destabilized as emoji proliferate amid text, but it also points toward a borderline that can be difficult to maintain or even discern in some contexts. As Mitchell puts it, "Among the most interesting and complex versions of this struggle is what might be called the relationship of subversion, in which language or imagery looks into its own heart and finds lurking there its opposite number" (43). So critics write with varying degrees of self-consciousness about "a language of graphics," using the metaphor of language to address its absence, part of a rich intellectual tradition that seeks to understand non-verbal knowledge as somehow systematic and therefore resembling language. Partisans of words likewise make damning recourse to imagery, as when Lessing himself charmingly considers the realm, the province, and domain of poetry, adopting spatial metaphors that work against his identification of poetry with time and not space.

We can glimpse a version of the same word/image struggle and confusion in centuries of mischaracterizations by Westerners about the nature of East Asian scripts, including the 19th-century Western invention of the ideograph as a way to think about East Asian writing.34 (Perry calls Chinese writing an "idiographic cypher," but linguists today would call it a logographic or logophonetic script.) Melville and the Romantics before him were steeped in the word/image struggle — Symbolism with a capital S and sublimity in a sense forged partly from its dialectic — evident for instance in the portent ascribed to Queequeg's tattoos. And what for centuries has been waged as a struggle rich in moral, aesthetic, and even cognitive presumptions has also been reducible to questions of technological affordance. That is, there are contexts in which technological capabilities help to determine what counts as text and what counts as image, if you will think again of D. Appleton's engravers and compositors or Google's scanners.

The distinction between linguistic and pictorial signs persists in some measure because of the different technical means — the media — by which words and images have been reproducible and transmissible. If Melville had needed any illustrations — he couldn't afford them— his publishers would have had them made separately from the typeset pages and by differently specialized means. Today authors still submit text and art to publishers in different files and file formats, largely because text and image are distinct from one another computationally, since images have generally not been processable, except with recourse to text. Search Flickr or other image databases, if you like, but what you are probably searching are hidden linguistic tags: text not image. As Matthew Kirschenbaum puts it, "Images remain largely opaque to the algorithmic eyes of the machine."35 That's why Google's scanners couldn't read Commodore Perry's engraved initial capital as a letter V amid the clutter of the pictured beach. Even texts that can be scanned successfully remain frustratingly like images if they haven't been properly subject to optical character recognition (OCR). (Returning to ye olde print shop, you might say that a scanned text that hasn't been subject to OCR — sometimes called a "page image" — is too much like a stereotype plate, a solid chunk, and not enough like pages standing in type.)

Admittedly, I am overstating this last point. We know that there are certain computational realms in which images are processable, fully encoded. Some are brand new and presage a truly momentous change. Google Photo can now sort your digital images for you, if you'll let it, and we know that the security state has been driving developments in fingerprint, facial, and other forms of biometric recognition. Image search is finally becoming a reality in some contexts, and image analysis, like translation, is a hot area for the application of machine-learning techniques. Zillions of tags added by humans, including, we can suppose, a goodly number of Amazon Mechanical Turkers, are helping to "teach" machine-learning algorithms to "see" image features, effectively opening the "algorithmic eyes" of the machine to image data.36 As with OCR, of course there are glitches. The algorithmic eyes make "mistakes." At least initially, it seemed that the training data and machine-learning algorithm behind Google Photo had normalized white skin, for example, so that the application has been less adept at identifying people of color.37 Like so many earlier innovations — and like Melville's Pequod — image analysis must be built on and out of human differences. I call these "mistakes" because at a certain level they aren't mistakes at all. The technology is working in exactly the way it has been constructed on precisely the data available so that any unintended, aberrant results must be traced critically, back to the ways that developers have generated and construed the data in question and designed the algorithmic means by which it is processed.38 Algorithms don't make mistakes; only people do.39

As momentous as image search really is, there are ways in which the computational availability of images is already well established. Think of CAD (computer assisted design) or, better, think of OCR itself. OCR depends upon a hardware-software combination that processes shapes (the shapes of letters) into linguistic components (encoded text). The development and use of OCR teaches us what we already know: writing as writing depends upon visual units of semantic value.40 Certain as we may be that pictorial and linguistic signs are categorically distinct from one another and chronically at war, alphabets and non-alphabetic scripts are essentially and by definition both pictorial and linguistic; they are "verbal imagery" in the first instance and of the finest grain.41 Thus emoji flourish as a cartoon army storming the citadel of words, but they also hail from a Lilliputian realm in which Mitchell's relationship of subversion is an operative necessity. Today, anyone creating a web page and needing a capital V or even a Maltese cross can decide to use either an encoded character or an image to represent the symbol in question, and there are good, practical reasons to do both, depending on what your expectations are. Encoded characters are useful because they can be searched, machine-indexed and analyzed, and they can be modified with a text editor in ways that images cannot. Image files, on the other hand, may end up being more stable in their appearance, if you think the matter of which they are part will be subject to font changes or other display modifications.42

Emoji aren't true writing, but they are handled as if they were. They are picked out individually from one character set among a menu of character sets, and they are digitally encoded just like the letters I word process in writing these lines. Each has an official name (which is in English), each has a code point corresponding to a bit value, and each has an abstract shape, a range within which variations remain intelligibly "the same." Just as "the same" letter can be represented in almost infinite variety — by any number of specific glyphs of various styles and sizes (fonts) and in anyone's handwriting — so the same emoji can also appear differently, less for aesthetic reasons in this case than for proprietary ones.43 "In the parlance of the gaming industry," emoji are "'skinned.'"44 That means that corporations like Apple and Google apply their own renderings for each character, something like a font, which they consider their own intellectual property. In the face of corporate competition, the underlying coherence of emoji and thus their broad transmissibility are based upon their description within the evolving Unicode standard, an international standard aspiring to describe the way that all written characters in all written languages get individually and uniquely encoded into sequences of ones and zeros for interchange and representation by different operating systems, platforms, and applications. Each emoji is everywhere encoded the same; different companies apply their own "skins" on the fly, and ever since Unicode 8.0 in 2015, users have been able to customize a few of those skins, picking from among six different skin tones for emoji that represent human features.

Unicode, as its name implies, is a unification, conceived originally in the late-1980s as a way to move beyond the parochial limitations of local standards like ASCII, which was great for English but not for other written languages. Basic ASCII is a 7-bit standard and has code space for only 128 characters, hence no £. Unicode was dreamed as a two-byte or 16-bit standard, with code space for over 65,000 characters. Back in 1988 that called for what one advocate called "перестро́йка (perestroika), i.e., restructuring our old ways of thinking."45 Published first in 1990-91, The Unicode Standard was subtitled Worldwide Character Encoding, Version 1.0. The worldwide ambitions it projects in this subtitle were simultaneous with another, better known effort, a memorandum by Timothy Berners-Lee and Robert Cailliau entitled "WorldWideWeb: Proposal for a HyperText Project" (1990). And just as the WWW emerged from the work being done at CERN — a European research center for particle physics — so Unicode 1.0 began by addressing the interests of those "most affected" by the lack of international coordination, identified as scientific and other publishers, bibliographical information specialists, and other academic researchers (1). One of the Unicode Consortium's earliest and stalwart participants was the Research Libraries Group (RLG), a small nonprofit consortium of North American research libraries that were already practiced with handling materials in multiple scripts. That said, the Unicode effort also attracted a veritable Who's Who from the technology sector, participants with additional interests at stake. The technical committee responsible for Unicode 1.0 included representatives from Xerox, IBM, DEC, Novell, Apple, Sun Microsystems, and Microsoft.

The RLG and Unicode Consortium were hardly the first and not alone in their ambitions to deal with the diversity of the world's writing systems. The administration of empires forms a context here, of course, while the history of international standards stretches at least as far back as the formation of the International Telegraph Union in 1865. Corporate efforts to internationalize telegraphy, typewriting, typecasting, typesetting, and word processing have all gotten caught up in complications arising from the world's many and diverse scripts. (Different writing systems use different character sets, but they also vary in things like directionality, use of vowels, diacritics, and context-dependent character forms.) Language reform — e.g., Romanization — was only one technique among several devised by entrepreneurs, governments, and others to accommodate non-Roman scripts in the service of modernity the world over, easing the electrical transmission of messages and the mechanical production and reproduction of writing. For instance, in 1928, the Turkish government under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk imposed a Roman alphabet (discarding Arabic) optimized for the phonetics of Turkish. East Asian languages, with their many thousands of logographic characters, phonetic elements, and multiple syllabaries, presented special, technolinguistic complications, as detailed in Thomas Mullaney's recent history of the Chinese typewriter. Mullaney shows that the effort to implement a subset of Han characters that might work in representing Chinese, Japanese, and Korean was first attempted in 1940 by a Japanese typewriter company seeking to supply its wartime empire.46

When the RLG and Unicode got started, East Asia thus demanded early attention. Based on work already being done by the RLG as well as in Asia, Unicode would begin by reducing Chinese, Japanese, and Korean scripts into "CJK," a single combined standard describing 27,786 fundamental characters, including both Han (Chinese) characters used in common by the three languages as well as characters from language-specific scripts like the katakana and hiragana syllabaries for Japanese, for example.47 Unicode's initial Han character repertoire drew on numerous standards developed in the different Asian nations as well as character encoding developed earlier for telegraphy and by IBM and Xerox.48 The Unicode Consortium devised a procedure for deciding when to merge Han characters from which of the source character sets, and when to let unique characters persist in the unified standard. It had its process "verified" by independent experts at the University of Toronto in 1991, about the same time that Unicode and China's own unified GB 13000 standard combined their efforts.49 For all of this, the Unicode code space already seemed impossibly small, while its international competitor, ISO 10646 (a 32-bit standard with code space for over 679 million characters) was way too big for software architecture of the time to handle.

Since these initial efforts, Unicode has continued to evolve and expand as it seeks buy-in as a worldwide standard. The nonprofit Unicode Consortium has expanded its membership, and new encoding techniques have radically increased the code space it describes. Joined with an improved ISO 10646 since Unicode 2.0, the standard now has code space for a little more than a million encoded characters. (As of Unicode 9.0, published in 2016, the standard describes 128,172 characters, leaving room for approximately 846,000 more.) Corrective interventions and competing schemes persist, but this has always been a specialists' domain. Until now. Much to the chagrin of diehard character-encoding geeks, Unicode makes headlines today only in relation to emoji.50 Forty years on, it has finally come to popular awareness, not as a worldwide encoding standard for scripts, but rather as an encoding standard for pictographic cartoons in a script-oriented setting. Should there be a taco emoji? Users (and Taco Bell™) say yes! If emoji are a cartoony gesture toward the universal language that they cannot be, then Unicode has been playing their straight man, managing worldwide transmissibility in its bid to underwrite (to encode) every and any written symbol stored or transmitted online, including the Maltese cross. What was for so long a black box for users — the largely unnoticed work of character encoding — is now a colorful arena for proposing and debating representative user interests. One recent addition to emoji (added March 2017) included additional flags (for England, Scotland, and Wales), Woman with Headscarf, a Curling Stone, Chopsticks, and Flying Saucer.

All of this is to suggest that Emoji Dick speaks both from and to an extended contemporary moment in which the image/text distinction exists under pressure, in which writing newly encroaches on oral-communication norms, even as the meanings (that is, the uses) of punctuation continue to puddle out, and in which global code space is finally — or at least increasingly — a reality: one encoding standard, all writing systems. For all of this, Emoji Dick is also born of an extended legacy of contact between East and West and a thicket of related technolinguistic concerns. A novel reimagined as piecework, the literary dialed down to the smartphone, a non-standard book-object nonetheless dependent on standards like Unicode, Emoji Dick asks us to consider the legacy of East/West contact as much in terms of media history as in terms of cultural exchange, international trade, or what Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels called worldwide "intercourse" (Verkehr).51 The East Asian histories of telegraphs, typewriters, and typecasting systems all have a bearing here, as do the various writing reforms proposed and effected in East Asia as part of the region's extended encounter with Western modernity over the past two centuries. Also germane would be the West's persistent imagination and use of the ideograph as a figure for mediation, a topos returning readers to certain assumptions about language and its inscription.52 Added to these concerns must be more recent patterns of use specific to Japan, such as cellphones embraced in Japan as a medium for writing fiction, and facsimile machines retained by Tokyo offices long after their disappearance in the West.53

While a thoroughgoing comparative history of cellphones still urgently needs to be written, the different histories of facsimile technology in Japan and the United States have been explored recently by Jonathan Coopersmith and are suggestive here, since these histories reconnoiter varied experiences of text and image, or, better, of text as image, since analog facsimile transmission — whether telegraphic or telephonic — obviates character encoding: faxes are typically texts transmitted as page images of themselves. Something like PDF files (developed in the early 1990s), they are great for sending and preserving layout. Facsimile telegraphs were developed in the U.S. and Europe as early as the late 1860s, when one preliminary rationale was transmitting East Asian scripts.54 The eventual uses of facsimile technology included niche applications like the transmission of signatures (by banks) and photographs (by newspapers), even as developers and entrepreneurs decade after decade predicted and failed to realize less specialized, breakaway success for the facsimile technology. Telephone deregulation — begun in 1968 in the United States and more suddenly in Japan in 1972 — would prove to be important, as would efforts by the International Telegraph Union to develop standards that might solve compatibility problems across competing devices. I won't rehearse the details. When fax machines finally did have their breakthrough moment — in the late 1980s — Japanese manufacturers dominated the market, so that Americans typically used Japanese machines. The fax machine was an essential office technology in the United States throughout the 1990s, but in Japan fax machines were also used in private homes. By 2002 more than half of all Japanese households had a fax machine, and faxes have persisted longer into the age of email and networked computers than they have in the U.S.55

Not only have the histories of fax and thus of page images been different in Japan and the United States, then, they have been intricately intertwined. Some of the differences might be ascribed to the divergent meanings of handwritten communications in both places (and thus tenuously as well to different scripts), but obviously there are a host of factors and contexts to consider, even beyond those mentioned here.56 That facsimile technology existed for more than a century before the breakaway success of fax machines as consumer electronics in the 1980s only confirms the radical contingency of media history. No technology determines its own meaning; instead, patterns of use emerge according to many variables. Over the long history of facsimile transmission, those patterns of use have negotiated and renegotiated the experience of page images as-and-in-distinction-from text, based upon communication norms among different groups of users.

Against this kind of media history Emoji Dick is a riff of sorts, calling our attention to mis- and non-communication as well as to workarounds, improvisations, and accommodations on a global scale and in the service of literature. Appearing just as the academy in the West re-theorizes something called "world literature," Emoji Dick fakes the export — the translation — of Melville's novel as it simultaneously evokes a succession of recent imports — manga, Pokémon, Hello Kitty, now emoji — that hail from Japan's culture industry of cute and that have arrived in the West on the heels of more consequential and less blatantly affective expressions of late capitalism. Think of Japanese manufactures, certainly — consumer electronics, microprocessors, automobiles — but think as well of the Toyota Production System or TPS. Critical successor to Fordism, TPS is a management philosophy and manufacturing system that has reengineered mass production as "lean" production, restructuring the increasingly automated shop floor for team-driven efficiencies and integrating logistics for just-in-time manufacture.57 Because Emoji Dick so ostentatiously depends upon recent innovations in knowledge work/Turk, it asks us to locate literature in and against a global history of labor and the means of production more generally.

Marx and Engels imagined the globalized means of production, a worldwide proletariat, and their Communist Manifesto correspondingly imagines world literature. "As in material, so also in intellectual production," they write: "From the numerous national and local literatures, there arises a world literature."58 They were picking up the concept from an earlier discourse, the "worlding" of literature enacted perforce by eighteenth-century Orientalist encounters with Asiatic writings.59 What they added was their own dialectic. As Amir Mufti explains, Marx and Engels saw world literature as a double-edged sword, complicit in the emergence of worldwide capital while also "pointing toward a distinctly human emancipation, the possibility of the overcoming of 'national one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness' and the inauguration of human 'communication' on a world scale." As a feature of bourgeois modernity, it puts native societies in jeopardy, yet it harbors progressive potential.60 Today world literature is partly a taste category, like world music, mapped to publishers' trade lists. It is also a disciplinary formation mapped selectively and often less than critically to college curricula. In this context, it has recently been described as a "mode of circulation and of reading . . . available for reading established classics and new discoveries alike," a description which — it must be admitted — works splendidly for literature in general, forget the "world."61

The contours of world literature are further hypothesized in libraries, where different cataloging systems differently model the world. To take only the case at hand, the U.S. Library of Congress acquired Emoji Dick in 2012 and catalogued it as PS2384.M6 2012. As such, Emoji Dick inhabits a unique niche on an imaginary shelf — a code space — appearing alongside every past and future Moby-Dick edition in chronological order, in a space identified for PS2384.M6. (Editions in English precede translations, and editions in general precede study guides and books about Moby-Dick.) The Library of Congress may store its copy in a special place — it has one signed by Benenson — and any local library may not even own a copy, but Library of Congress cataloging imagines a total world library, and, with the help of cataloging giant OCLC, it helps every other library that follows its cataloging system to imagine the same total library. Real libraries, bricks and mortar, each offer unique scale models, since their books are shelved in the order prescribed by the LC system. As the imagination of a total world library, LC's cataloguing system has the capacity to uniquely identify every existing or potential book, where "potential" gestures not toward infinite, monkey-typed or machine-generated permutations — a la Borges's Library of Babel — but rather toward the productivity of known, describable agencies: authors, compilers, editors, translators, and publishers. Still, a total library — a world library — is a staggering proposition, and not without pitfalls both practical and intellectual.

At a practical level, mistakes are made. The OCLC catalog — its public access version is called WorldCat — is crowd-sourced by librarians, who describe the new books they acquire. (Librarians arguably invented crowd-sourcing, coordinating cooperative cataloging projects across special-purpose digital networks.) Newness can sometimes be difficult to gauge, however, so duplicate entries crop up. WorldCat catalogs the same edition of Emoji Dick in three different ways, for instance, so that as of this writing it has three different OCLC control numbers. A library in France punctuates its title with a colon, Emoji Dick: Or, the Whale, and includes three different subject headings: "Smileys"; "Ahab, Captain (Fictitious character)—Fiction"; and "Whaling ships—Fiction." The Library of Congress demurs on Smileys, but includes the subject heading "Whaling—Fiction" and "Picture-writing in literature." It speculates place of publication as "[Virginia?]," while another library supplies the information that Lulu.com is based in North Carolina. It would seem that books — even books lying open on the desk in front of you — can be tricky to describe with any great precision.

At an intellectual level, cataloging can be even more vexing. "PS" is the call letter for American literature, and PR for British. Class P generally "includes philology, linguistics, and literature." When the classification was elaborated, "German, Dutch, and Scandinavian literatures received a separate call letter, PT, whereas all 'Oriental' Literatures were subsumed under PX." The world of world literature so rationalized is a lopsided construct indeed, shaped and radically misshaped by a host of historically and culturally specific judgments and assumptions about literature, literary cultures, and the global potential of the knowledge projects so entailed.62 If Melville's Ishmael sets out whaling "to see the world" (71); seeing the world in world literature turns out to be a complicated proposition.

Whether one is for or against world literature — because of its "translatability assumption," its residual imperialist contours, or otherwise — the formulation at least helps to conceive a global system of literary production and consumption that is predicated on the flow of cultural and other forms of capital.63 It even "becomes possible," Pascale Casanova writes, "to measure the literariness (the power, prestige, and volume of linguistic and literary capital) of a language, not in terms of the number of writers and readers it has, but in terms of the number of cosmopolitan intermediaries — publishers, editors, critics, and especially translators — who assure the circulation of texts into the language or out of it."64 Likewise we might measure the relative scientificness of different languages, judging from a fascinating book by historian Michael Gordin.65 Science, at least, is international in the way that Marx and Engels imagined — scientific knowledge is knowledge everywhere, no matter its nation of origin — and it is assumed to be more translatable than literature. Yet, scientific publishing too has from its origins been intricately structured by linguistic politics. No surprise: different discourses—literature and science — function differently along the trajectory (which Marx and Engels did not imagine) toward Global English. Put another way, if Global English is itself an elite discourse of contemporary capital (and correspondingly the idiom of standards bodies), its cooption or infection of existing discourses remains uneven and heteromorphic.66

Encountering Emoji Dick is thus partly an encounter with multiple, presumptive efforts at "worlding," and any adequate account of Benenson's project must puzzle the world at stake. It is a world made adequate to TPS and emoji: technically advanced, industrially integrated, bureaucratically managed, standards-dependent. "Following Heidegger's suggestion that in modernity the world has come to be grasped and conceived as 'a picture,'" Rey Chow writes, "we may say that in the wake of the atomic bombs the world has come to be grasped and conceived as a target — to be destroyed as soon as it can be made visible."67 Following the "age of the world picture" and the "age of the world target," Emoji Dick points facetiously to world literature, as if to remake the world picture as world communication, the non-writing of pictographs acting as a decoy for an underlying and totalizing encoding standard for writing in the context of computing. So, two cheers for world communication?

III.

"I have swam through libraries and sailed through oceans" (136).

My students have observed that half the fun of Emoji Dick is saying it. They like the word dick, yes, but there is pleasure in the whole title. The word emoji, like the word perestroika is an untranslatable. It functions as a "checkpoint," marking a historically specific zone of contact and frisson between languages, the paradoxical crux of incommensurability and pleasurable accommodation.68 And just as perestroika is a Romanized untranslatable that we can date to the Gorbachev era of the 1980s, emoji is a transliterated untranslatable evolved in and of our networked present. Like other untranslatables, it can be reckoned "as a linguistic form of creative failure with homeopathic uses."69 Both failure and homeopathy in this case are keenest with regard to "emo-," which is formed in Japanese by combining lexical elements to signify picture + writing and thus has nothing whatsoever to do with the "emo-" in emoticon or emotion or with "emo" as a style connected with an American popular music scene and, at least stereotypically, as an affect associated with a kind of youthful nihilism. Anglophones get something in the word emoji that isn't there in Japanese. There's no precise term for this sort of slippage — it's not a cognate, a homonym, a mondegreen (when you hilariously mishear a lyric), or a misappropriation of a foreign word — it is simply an arbitrary surplus, a modest semantic profit taking or sense-making by speakers of English as they encounter the word emoji along with the character set it describes.

There is still further gain in the partial rhyme of Moby and emoji, which works to supplement the problem of naming that the spouting whale icon presents in Benenson's title. Crucially, Emoji Dick retitles Melville's novel without renaming its white whale. Eponymy flickered from the first, since in 1851 Moby-Dick featured Moby Dick, the whale: no hyphen. But here eponymy short-circuits entirely. Emoji Dick refuses the identity of whales and books upon which Melville's big novel seems premised. That premise is nowhere more clear than in Chapter 32, "Cetology," in which Melville's narrator tries to offer a systematic account of the varieties of whales. Because Melville's is a book at some level about books, Ishmael does this bibliographically, by dividing whales into formats: giant folio whales, smaller octavo whales, and the little duodecimo whales. To the extent that Emoji Dick plays with Melville's identification of whales and books — of Moby-Dick the novel and Moby Dick the character — it is only on the most slender grounds: Emoji Dick is a big white codex, and it's unreadable. If — as my students say — half the fun of Emoji Dick is saying it, then the other half is not reading it.

For the record, Moby-Dick itself is famously unreadable, larded with one long excursus after another on subjects relating to whales and whaling. As a result, American popular culture has turned Moby-Dick into a punch line forever waiting for its next joke. Monomaniacal Ahab has become a stock character, "Call me Ishmael" a tag line, and the sheer monumentality of Melville's tome the invitation to a gag. Woody Allen's Zelig (1983), to take only one example, is a mockumentary about an eponymous anti-hero who becomes a human chameleon, able to morph in size, shape, skin tone, diction, and expertise according to the people around him. Zelig begins his entire identity-blending career — baby steps — by pretending to have read Moby-Dick among a group of people discussing it at a cocktail party. Students of literature do read Moby-Dick, of course, and I commend it to your attention. Not reading Moby-Dick is a shame. Not reading Emoji Dick is the point.

Thus, Moby-Dick and Emoji Dick differently call attention to not reading as an element of popular discourse, part of and party to the ways we have come to think and talk about reading at the present time.70 And it is striking just how different the different kinds of not reading seem to be. There is the not reading done by college students in the U.S., for one, who are everywhere deserting the traditional literature majors for what they have been led to believe are more practical fields. The English major, once the paradigmatic liberal arts concentration, has been hemorrhaging students, with some campuses reporting declines by 30 or 40 percent over several years.71 Mostly anecdotal evidence suggests that students are more and more vocationally oriented, while many are simply pursuing newer, less traditional disciplines in the arts and humanities.72 Creative writing and media studies, for example, have both seen increased enrollments on campus. But there are other distinct species of not reading that warrant attention too. I refer on the one hand to the not reading of the literary-critical methodology called "distant reading," and on the other hand to the not reading to which a variety of contemporary literary expressions differently seem to aspire.

So-called distant reading productively uses statistical and computational methods to "mine" (that is, to analyze) vast textual corpora with the preliminary rationale of getting beyond the relatively tiny number of literary works, the "canonical fraction," which any of us can hope to read in the course of a lifetime.73 Not reading actually works on two alternative levels at once in this formulation. First, its critics sniff that distant reading — machine reading — isn't really reading at all. And second, the canonical fraction is a reminder that a hugely gigantic proportion of the books ever written and published are simply not read. Consigned to oblivion, most are works we've never even heard of and never will.

Not reading of an entirely different stripe has emerged in contemporary literature, where certain works may be said to beg for it. For instance, there is the long "tradition of poetic illegibility" explored by Craig Dworkin in Reading the Illegible. Here Dworkin focuses on modern and postmodern works that include overprinting, redaction, cancellation, erasure, and other techniques that make them unreadable in part or in whole (xxii). In his subsequent No Medium, Dworkin goes even further, focusing on artistic works — books, but also films, recordings, and other media — that are simply (or, as it turns out, not so simply) blank. Closely related are works within the realm of what has been called "conceptual poetics." Here Kenneth Goldsmith is probably today's foremost practitioner-provocateur, well known for his exertions in what he himself has described as "uncreative writing." Examples include his notorious poem "The Body of Michael Brown" (a modified transcription of the autopsy of Ferguson victim, Michael Brown, which Goldsmith performed at a reading in 2015) as well as earlier "uncreative" works. My favorite is Day (2003), which republishes a single day's issue of the New York Times as a massive, 835-page paperbound codex. Day compares to Benenson's book in its scale, certainly, making another big book out of an ephemeral non-codex form. Benenson's book is built as if in texts and tweets, that is, the way the Goldsmith's is built on the newsprint in his recycling pile. But Goldsmith transcribed his text laboriously by hand, so he has always said.74

Here again, with Day as a prompt, not reading operates on two levels. First, conceptual works like this tend to garner "thinkerships" more than they do readerships, as Goldsmith puts it.75 Open Day and the eyes quickly glaze. Second, faced with the ponderous weight and laughable bulk of Day, it becomes clear that the daily newspaper, any day or every day, simply isn't read — it is always not read — cover-to-cover. This seems like yet another distinct form of not reading, one that we experience as fully determined by media, since it is the quantity, heterogeneity, and piecemeal presentation of the newspaper (not to mention its unrelenting refresh rate) that works to discourage or disable a thorough reading. Media-determined not reading is having its day today, not so much in relation to newspapers as in relation to the world online, as critics, educators, journalists, and researchers describe and diagnose "hyper reading," the kind of not reading that is supposedly native to the computer screen. We click through hyperlinks, scroll down screens, jump from one window to another, multitasking all the while.76 Hyper reading — a bit like reading a newspaper — involves absorbing layout and design as part of the process of reading some bits and leaving others unread, pursuing some links and ignoring others, whether according to method, habit, whim, or fancy. It means absorbing superabundance and navigability as framing conditions. And unlike reading a printed page, it means acceding to the multifarious role of "user," as each of us become at once the interacting subject of an application interface, operating system, and networked device.

Take just one relevant example, Moby-Dick rendered as a blog: "The Time I Spent on a Commercial Whaling Ship Totally Changed My Perspective on the World" was posted by "Ishmael, Sailor" on the humor site Clickhole.com in August 2014.77 The sailor's lengthy post begins, "Call me Ishmael." It contains the full text of Melville's novel and is appended by three tags: "Whaling," "Inspirational," and "Wow." (Hint: it uses a capital L for the British pound sterling.)

No one would ever actually read Goldsmith's Day or Clickhole's "The Time I Spent," yet both have plenty to suggest about reading and not. To scroll through Moby-Dick reformatted as a blog entry is to recognize anew the ways that screen environments seem to trigger browsing instead of reading. Here, without page numbers or embedded anchors to orient the reader, just chapter titles and an occasional pull quote, Melville's work invites a quick dip or just a giggle, not any lengthy navigation. Both newspapers and the blogosphere encourage — indeed rely upon — not reading. Chalk it up to the affordances of different media and different formats, perhaps, but these are forms of not reading that point as much to the social functions of publication as to newsprint and posting online. The title Day points ambiguously to the day before (in general, today's printed news happened yesterday) and the day of. The defining ephemerality of the news, its never ending cycle, day by day or 24/7, helps to produce conditions of continuous and perpetual not reading, which paradoxically delimit not reading of yet another kind, since old news: there's no point in reading that.

Clearly, not reading is a category even more capacious than reading, and it cannot be my business here to taxonomize its extent or to explore its history in full. Even were we to limit ourselves to not reading books, the subject is no more manageable. Pierre Bayard's waggish How to Talk About Books You Haven't Read presents a brief for several different species of not reading, arguing that the stigma attached to not reading is actually disabling of true participation in the culture of books. Cultural literacy depends upon the ways we inhabit reading and not reading together. Instead of a sharp line between the two, we should consider a capacious borderland where techniques like skimming, reading reviews, and establishing context among books (without even opening them) all allow reasonably intelligent people to participate in meaningful conversations about books, even conversations with professors of literature or with the authors of the books in question.78 The psychic operations involved in discussing books are paramount, for in Bayard's view, the books we talk about are screens, "substitute objects we create for the occasion," maintaining "a consensual space," wherein we "speak about ourselves by way of books."79 Talking about books you haven't read in this sense turns out to be inevitable, self-aggrandizing, and yet also ultimately healthy. In this iteration, not reading is a canny timesaving practice that cultivates selfhood, providing a stage for encountering the Other while it lays the groundwork for mature self-possession.

Beyond these examples, we might consider how the not reading of today compares to earlier forms, as well as how not reading variously entails and delimits reading itself, mobilizing a host of changing assumptions about readers and the conditions of readership. But such a project must wait for another day. Certainly Emoji Dick, like so much not reading at present, responds to and emerges from the contemporary logic of computation, with its structured hierarchies and transmission protocols. And it turns out that we have been worrying the fate of reading in an age of computers since at least 1955, when the University of Chicago Library School convened a future-of-the-book conference under the shadow of cybernetics.80 If Emoji Dick is a conversation piece or an object lesson, it's a conversation piece well suited to a conversation that we've been party to for some time. Emoji Dick helps raise the question of how literature — itself a culturally and historically specific "mode of circulation and of reading" — may be faring under like conditions. The literary is a principle of thrift, a classification of discourse, which emerged and evolved amid the proliferation of printed meanings.81 What will its futures be amid the superabundance of digital meanings? It's hard to say.

A troubling glimpse beyond that very horizon may be had in the pages of Chinese artist Xu Bing's From Point to Point. Part of an extended and multiform project called the Book from the Ground, From Point to Point is a slim volume published in connection with exhibitions in the United States and elsewhere.82 On 112 numbered pages and in 24 chapters it tells the story of a day in the life of a man, a modern everyman, who is represented by the icon familiar from the doors of men's rooms the world over. He and his entire story are rendered in pictographs, icons, and other graphic symbols, including emoji. As part of Book from the Ground, Xu Bing and his studio have spent years harvesting and rendering a vast repertoire of pictographs and other symbols that they have found being used in bathrooms, on airline safety cards, as corporate logos, and in other contexts. In 2007, the Museum of Modern Art in New York showed Xu Bing's Book from the Ground, "Icon Chat Software," which allowed museumgoers to communicate in icons between two computer terminals. A recreation of Xu Bing's Book from the Ground studio has also been exhibited, complete with furniture, icon editing software, notes, and photographs. There have been a related animated film and also a related pop-up store in Shanghai. And in association with an exhibit at MASS MoCA in 2012, the MIT Press published The Book About Xu Bing's Book From the Ground as well as a sizeable edition of From Point to Point.83 From Point to Point has been called the culmination of Book from the Ground and also just another of its many manifestations as an ongoing and unfixed work of art. Xu Bing himself describes it as "a book that anyone can read," one that strives "to treat [all readers] equally."84 This is less a populist or democratic ethos than it is a globalizing one. No matter what language(s) they speak, that is, "readers" can figure out the narrative in From Point to Point if they are savvy enough to recognize various icons, puzzle out others, and accede to their presentation according to certain text-oriented norms. (From Point to Point is conventionally punctuated, it reads from right-to-left and top-to-bottom, and it adapts the conventions of cartoons to include parentheses-like thought and speech balloons.) Anglophone readers who want to go further can read the "From Point to Point, Pages 1-112 English Translation," which appeared in The Book About along with articles by Xu Bing and others. Whether read in translation or "read" pictographically, it's the story of an office worker (translated as "Mr. Black"), who wakes up, defecates — the poop emoji — feeds his cat, and hustles to work. There he interacts with friends and coworkers and fields a phone call from his mother who nags him about finding a wife. He uses an online dating site to arrange a date for that evening. He has coffee, has lunch at McDonalds, and later nervously gives a presentation for his boss and others. It goes well, even though he really has to use the bathroom. Later, he goes home to change and has a date with "Miss Violet"; takes noodles to his sick friend, "Mr. Red"; has beers with a broken-hearted friend, "Mr. Green"; and finally arrives home again; flips some channels on TV and falls asleep; dreams; is tormented by an insect; eventually plays some video games; and has to hustle off to work again in the morning.