Unpredictable: Three Days of the Condor, Information Theory, and The Remaking of Professional Ideology

A third of the way through Sydney Pollack's spy thriller Three Days of the Condor (1975), the freelance assassin Joubert (Max von Sydow) explains to his client his difficulty in locating the CIA researcher codenamed Condor (Robert Redford), who went on the run after Joubert murdered his entire unit in an early moment of the film. "Condor is an amateur," Joubert explains, "He's lost, unpredictable, perhaps even sentimental. He could fool a professional, not deliberately, but precisely because he is lost. He doesn't know what to do."1 Against the backdrop of the Lincoln Memorial, this scene establishes the first in a series of distinctions between "professionals" like Joubert and "amateurs" like Condor — a distinction that here hinges primarily on differences in knowledge but will expand to include several other qualities. The amateur, according to Joubert, is "lost" in the world of covert operations and "doesn't know what to do." But this ignorance brings with it unexpected benefits. Unschooled in the practice of spy craft, Condor avoids becoming, in Joubert's word, predictable. This unpredictability saved his life during Joubert's original assault on his unit — Condor had broken regulations and snuck out the back door to go to lunch — and it provides him with his canniest solutions in those moments when Joubert gets too close. If, to quote Bernard Bledstein, a historian writing the year after Condor's release, a "professional person" such as Joubert "grasp[s] the concept behind a functional activity, allowing him both to perceive and predict those . . . unseen variables which determine an entire system," Three Days of the Condor suggests that the amateur's ignorance of those variables provides him with a certain freedom of action.2 The amateur might not make an educated decision, but neither will he make an obvious one.

Joubert's distinction between amateurs and professionals initially separates not only the untrained and naïve from the expert and worldly, but also the upstanding and morally sound from either the amoral (Joubert) or the ethically compromised (Condor's CIA colleagues). Yet the distinction between amateur and professional gradually breaks down over the course of the film, which suggests that what Joubert represents as a binary opposition is in fact a continuum and that mapping the movement from one pole to the other — amateur to professional, ethical to compromised — is a central function of the narrative. Of course, neither this opposition nor its undoing is original to Three Days of the Condor. Stories of amateurs caught up in geopolitical intrigues are common in spy narratives, which Michael Denning argues have, since the 1960s, frequently served as "cover stories of white-collar work," a means to think about and through the professional-managerial class (PMC).3 Three Days of the Condor is notable for how little "cover" it bothers to provide; the film's explicit critique of the professionalized CIA allows its filmmakers, in the words of director Sydney Pollack, to explore "certain ideas of suspicion, trust, morality ... using the CIA almost as a metaphor, and drawing certain conclusions from post-Watergate America."4

Those conclusions were familiar in "post-Watergate America." By the mid-1970s the professional-managerial class, the ideologies that legitimated it, and the technocracy over which it presided had become the subject of considerable academic and popular scrutiny.5 The United States' failures in Vietnam, the oppositions posed to the postwar status quo by the Civil Rights, Women's Liberation, student, and counter-cultural movements, and the corruption exposed by the Watergate scandal raised significant questions about the PMC's claims to represent, in Alvin Ward Gouldner's phrase, "the paradigm of virtuous and legitimate authority, performing with technical skill and with dedicated concern for the society-at-large."6 When Three Days of the Condor was released in 1975, many Americans concurred with the notion, as described by Paul Goodman, that PMC workers were not "autonomous men, beholden to the nature of things ...[and] bound by an explicit or implicit oath to benefit their clients and the community," but rather "liars, finks [or] mystifiers ... coopted and corrupted by the System."7 Yet the film differs from other spy narratives and "post-Watergate" critiques in further specifying its distinction between professionals and amateurs through Joubert's third term: unpredictability. Predictability and its opposite are crucial concepts in the film, enabling not only Condor's escapes from Joubert but also his impulsive alliance with a photographer named Kathy, his unexpected ally in exposing the rogue CIA unit. Predictability connects Condor's investigation of the professional CIA with contemporaneous analyses of the technocracy — the nexus of state and private institutions that structure late capitalism and also the mindsets and methodologies designed to insure its proper functioning. Technocracy "is the ideal men usually have in mind," Theodore Roszak explains, when they strive "for efficiency, for social security, for large-scale co-ordination of men and resources, for ever higher levels of affluence and ever more impressive manifestations of collective human power."8 Most importantly, for my purposes, predictability and unpredictability unexpectedly align Three Days of the Condor with the postwar discourse of information theory — in which predictability specifically enables the abstraction and quantification of information — and the social scientific work that discourse engendered in the fields of linguistics and semiotics. That discourse was a crucial part of a larger midcentury effort to apply scientific methodologies to the social sciences and the humanities and subject a messy human world to the rigors of professional attention.

In what follows, I map the shared territory of Three Days of the Condor and information theory to explore the film's engagement with postwar technocratic cultures and their PMC administrators. Recent analyses by Jerome Christensen, JD Connor, Jeff Menne, and Derek Nystrom explore how Hollywood filmmaking was itself becoming one of those technocratic cultures, revealing the implications of the postwar rise of the professional-managerial class for the US film industry.9 The corporatization of the classical-era studio in the 1960s, growing professionalization of the filmmaker's trade by the film schools, and rise of auteurist discourses of autonomy and independence — if not their actual manifestation — provided 1970s filmmakers with new dynamics that reinvigorated Hollywood's longstanding tendency to make its movies "on some level ... about the business."10 Three Days of the Condor's opposition of amateurs and professionals shares in a broader New Hollywood-era engagement with the twinned phenomena of corporatization and professionalization, the narrative interactions of their various embodiments, and, in J.D. Connor's phrase, "the fiction that the contest for preeminence is fundamentally one between individuals and institutions."11 Amateurs and professionals, individuals and institutions: these binaries are repeatedly shored up and broken down in the films of the 1970s.

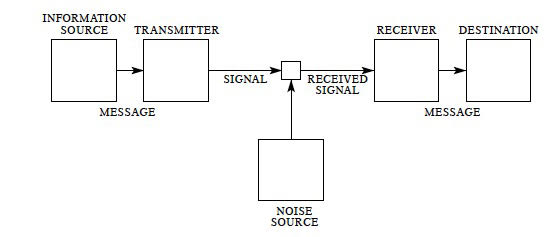

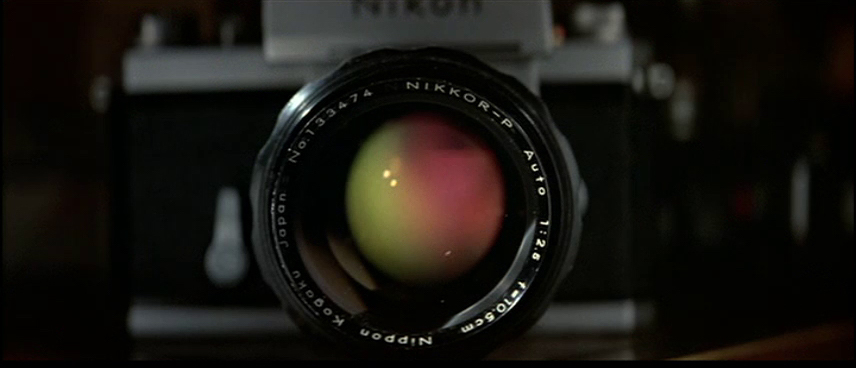

Less evidently did movies of this era think through theories of mathematics and engineering, though information theory had achieved remarkable mainstream awareness by the mid-1960s.12 Developed by engineer and mathematician Claude Shannon at Bell Laboratories in a paper from 1948 titled "A Mathematical Theory of Communication," information theory enabled the creation of complex technologies for the efficient encoding, transmission, and decoding of messages.13 The theory is centered around Shannon's schematic diagram of a general communication system through which Shannon, in Bernard Dionysius Geoghegan's words, "mapped out a new series of functions that formed the basis for professional specialties and specialized instruments" and established "the most efficient distribution of labor among humans and machines" (Fig. 1).14 Conceiving of messages not as specific semantic entities but rather as generalized and abstracted concepts, Shannon redefined the term "information" away from semantic content and engineered a breakthrough in the quantification and transmission of messages. The resulting theory, and the field of cybernetics to which it was soon linked, proved highly influential as scholars from fields as diverse as physics and mathematics to linguistics and anthropology perceived an interdisciplinary potential in the fields' paradigms of message, code, signal, and information. Recent work has traced the rapid dissemination and remarkable influence of Shannon's theory on social scientific work during the immediate postwar period; scholars such as Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead imagined that information theory, in the words of Robert R. Kline, "would bring the rigor of the physical sciences to the social sciences" and function as a "universal language...to bridge disciplinary boundaries" between them.15 Themselves abstracting Shannon's work from its basis in a quantified notion of information, these scholars applied information theory as a concept and a metaphor in numerous social scientific and linguistic contexts.

Fig. 1 Shannon's schematic diagram of a communications system from "A Mathematical Theory of Communication"

By the mid-1960s those efforts had begun to dissipate — not least because of Shannon's open chagrin over the "extraordinary amount of publicity in the popular as well as the scientific press" that information theory received.16 In a 1956 paper amusingly titled "The Bandwagon," Shannon requested that "workers in other fields" exit the vehicle, noting that "the basic results of the subject are aimed in a very specific direction, a direction that is not necessarily relevant to such fields as psychology, economics, and other social sciences."17 Yet the consequences of midcentury efforts to apply information theory to the social sciences and linguistics can be found in work by Claude Lévi-Strauss, Roman Jakobson, and Roland Barthes. When Lévi-Strauss describes the bricoleur's scrutiny of an "already existent set made of up of tools and materials ... to discover which of them could 'signify'" and Barthes characterizes the photographic image as a "message without a code," we see the residue of interdisciplinary interest in Shannon's theory.18 More specifically, Barthes uses concepts born from information theory to parse the distinctive ways in which photographic signs are simultaneously denotative and connotative, the sematic implications of their imbrication, and ultimately the role that the random, accidental, or unpredictable plays in photographic meaning.

Nevertheless, to consider a 1970s spy thriller in relation to information theory and semiotics will seem counterintuitive. There is no obvious reason why such specialized fields would inform Pollack's clever, if generic, Hollywood film. I do not argue for a direct influence of the former on the latter, though I am tempted to: both communication technologies and semiotic systems are essential to its narrative and a handful of specific moments encourage such speculation. Not least, a pivotal set of scenes turn around Condor's ability to manipulate the New York Telephone switching system with its prominently displayed Bell Systems logo (Fig. 2). But I am more interested in how Three Days of the Condor, information theory, and Barthian semiotics unite through a shared discourse of message, code, predictability, and randomness, a shared interest in communication and representational technologies such as telephones, computers, writing, and photographs, and ultimately, a shared concern with the challenges posed by and opportunities inherent within semantic meaning. Pollack declared in 1976 that he prefers to "work within genres — a western, romance, melodrama or spy film. And then, within that form, which I try to remain as faithful to as I can, I love to fool around with serious ideas."19 I argue that in Three Days of the Condor the Hollywood spy thriller operates as a code through which Pollack explores "serious ideas" about postwar technocracies and the PMC labor that works for them. How do individuals operate within or alongside institutions? What work does amateurist discourse perform for a professionalizing industry such as Hollywood filmmaking? The question of professionals and amateurs encodes the film's larger concern with the nature of institutions and their relations with individuals.

Fig. 2 The Bell Systems logo features in the film's mise-en-scène.

Deciphering that code reveals the centrality of new class concerns to Three Days of the Condor as well the film's challenge in maintaining its central oppositions. I examine Shannon's "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" and three of Barthes's works on photography — "The Photographic Message" (1961), "Rhetoric of the Image" (1964), and Camera Lucida (1980) — to reveal the film's response to a technocratic ideal that imagines information as an abstract, quantifiable entity emptied of semantic content. Condor's efforts to defeat his CIA administrators are predicated on a semantically rich mode of reading that privileges interpretation and the quest for meaning as a distinctly human, countercultural practice. If technocracy's "great secret" was its success in convincing ordinary citizens that "the vital needs of man are ... purely technical in character" (Roszak, 10), Condor's talent lies in his ability to use hermeneutical methodologies to counter the dehumanization feared to be the consequence of such beliefs. He interprets both written and photographic texts in his effort to outwit the CIA, but ultimately, it is his ability to interpret the inevitable yet unintended aspects of the photographic image that makes the crucial difference in his search. That unintended material — what Barthes would come to call the punctum (as distinct from the stadium), a "co-presence" in the image that just "happened to be there" — Shannon would call noise.20 Shannon's communications systems were designed to remove noise from significance through the proper coding of the signal; Condor's success depends precisely on his ability to make that noise semantically relevant, to make it mean. If Shannon's communication systems deploy predictability to defeat noise, Condor deploys noise to defeat predictability. He stakes his future on the human capacity to comprehend meaning, to read stories rather than play games, and the film's ambiguous ending is itself an invitation to interpretation. Yet while Three Days of the Condor endorses Condor's amateur ideals, I argue it is in the slippery boundary between professionals and amateurs that resides the film's most compelling observation.

Professionals: "The belief is in your own precision"

In his discussion of conspiracy thrillers from the 1970s Fredric Jameson observes that "If everything means something else, then so does technology."21 He includes Three Days of the Condor among those films in which we might register a transformation of the filmic landscape into corporate and technologized spaces that function allegorically to represent "the world system of late capitalism."22 Images of information and communications technologies are the backdrop to the opening credits; shots of D.C. landmarks and travel infrastructure (highways, bridges, trains, and helicopters) provide visual interest behind telephone conversations presented in voiceover, and repeated images of the World Trade Center are photographic signifiers for "the whole unimaginable decentered global network" that defines late capitalism.23 An arguably more contemporaneous term would have been "technocracy": in the late 1960s and 1970s, Theodore Roszak popularized the term, using it to diagnose a change in "the meticulous systemization Adam Smith once celebrated in his well-known pin factory" that now extended "to all areas of life, giving us human organization that matches the precision of our mechanistic organization," orchestrating "the total human context which surrounds the industrial complex."24 More specifically, these opening shots represent spatially the intelligence apparatus that was established after World War II and became increasingly technologically dependent over the 1950s and 1960s, and the corresponding "regime of experts" that grew up to ensure its proper functioning25.

The professionalism of those experts was of paramount concern for the founders of that intelligence apparatus.26 One of its early theorizations, Sherman Kent's Strategic Intelligence for American World Policy (1949), repeatedly evokes professional ideologies of objectivity and proficiency in its conception of the "[p]roper relationship between intelligence producers and consumers," arguing that "Intelligence must be close enough to policy, plans, and operations to have the greatest amount of guidance, and must not be so close that it loses its objectivity and integrity of judgment."27 By the early 1970s, Kent's image of "objective and impartial" intelligence officers had been tarnished by piecemeal revelations about CIA conduct in Vietnam and elsewhere, and was definitively shattered in late 1974 when the New York Times exposed the CIA's illegal domestic surveillance of anti-war and other dissident organizations.28 In Three Days of the Condor, Kent's professional Company man is replaced by an image of unscrupulous technocrats whose members meet, Star Chamber-style, in an anonymous boardroom at Five Continents Imports, Inc. The film offers four iterations of the PMC-era CIA agent, figures who operate with varying degrees of autonomy within the intelligence technocracy: Joubert, the assassin-for-hire; Mr. Wabash (John Houseman), the apparent head of the intelligence apparatus whose actual position is never fully specified; John Higgins (Cliff Robertson), Deputy Director for New York, whose concern with uncovering the rogue unit is marred by his commitment to protecting the CIA from scandal; and Leonard Atwood (Addison Powell), Deputy Director of Operations, who, we eventually learn, created an unauthorized operation to seize oil fields in the Middle East and ordered the murder of Condor and his colleagues to cover it up. As in many spy films of the era that explore the professional-managerial strata, these characters allow the film to raise repeated questions about autonomy, agency, and the nature of PMC labor.29

The contract agent Joubert embodies the furthest pole on a continuum that runs from amateurs to professionals. Highly skilled, available for hire, and disconnected from either public or private institutions, he is simultaneously independent and circumscribed by his status as a contract employee. He is free to choose his clients — within the requirement of earning a living — but once he does, the client's needs alone determine the nature and breadth of his activities. Joubert's self-proclaimed professional status suggests not only the imprecision of professional categorizations — sociologists would not put assassin on any list of professions — but also the outer limit of their ethical commitments. His detachment from the consequences of his labor reminds the viewer that at one extreme, the professional worker is a mercenary figure whose "proficiency is for sale [and] it is the buyer/employer who provides the task or goal," as Bruce Robbins has written.30 PMC ideologies insist that professionals maintain extra-market commitments — to the physical well-being of one's clients (doctors), the impartial functioning of the legal system (lawyers), or the advancement of knowledge (academics) — that circumscribe their participation in the marketplace; in Paul Goodman's words, the professional is "bound by an explicit or implicit oath to benefit their clients and the community."31 But Joubert's commitment to his client overrides any other ethical considerations and distances him from the social consequences of his labor. He embodies what sociologist Steven Brint terms "expert professionalism": a subclass of PMC workers that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as a consequence of key shifts in the professional marketplace. Emergent new technologies and the theories that undergird them promised "control over complex systems, both natural and social"; demographic changes created an explosion in the college-educated population, an increase in market competition, and a push for increased specialization; and evaluations of status began to consider professionals' standard of living — their earnings — of greater import than their service to their communities in calculations of professional prestige.32 As Brint describes, these changes led to the increasing adoption of "expertise-based understandings of professional standing, while tending to abandon understandings based on the ideas of social trustee professionalism."33

Narrowly specialized, such professionals think "more exclusively as entrepreneurs and less as members of an occupational collective," severing their ties to other professionals, organizations, and institutions.34 Expertise is valued in and of itself and not for its capacities to advance abstract values regarding the welfare of a community. It operates as a "negotiable resource" brought to "a labor market in the form of credentials and expert knowledge."35 As Joubert explains to Condor, when he is hired to assassinate someone, he doesn't much "interest himself in why." He thinks instead "in terms of when. Sometimes where. Always how much." His occupational mastery is matched by an ethic of service — an ethic that leads him to offer a free assassination to apologize for having been "careless with Condor" — but that ethic, far from benefiting the community, endangers other dedications: to institutions, to country, to ideologies beyond the professional. As Joubert explains to Condor at the end of the film, the contract professional lives a life that is "almost peaceful. There is no need to believe in either side. Or any side. There is only yourself. The belief is in your own precision."

Yet even as Joubert represents the extremes of expert professionalism in "the world system of late capitalism," he is not the principle object of the movie's critique.36 As Pollack observed, "The von Sydow character is an honest bad guy, which I prefer any day to a lying good guy" — of which the film offers at least two examples.37 John Higgins and Leonard Atwood embody the other end of a PMC labor spectrum: the PMC worker as Company-man, positioned within and aligned with an institutional hierarchy. The film reveals the three men to be connected when Higgins admits to Condor that he knows Joubert "professionally"; "he worked for the agency once," Higgins acknowledges, and is a member of "the intelligence community." Workers such as Higgins and Atwood were a matter of consternation to sociologists during the New Class debates in the 1970s. As Barbara and John Ehrenreich argue in "The Professional-Managerial Class" (1977), though "the roles the PMC was entering and carving out for itself ... required a high degree of autonomy, if only for the sake of legitimization," the realities of postwar corporatization meant members of so-called high or classic professions (doctors, lawyers, academics), lower-status professional workers (engineers, nurses, social workers), and administrators and managers were increasingly likely to work within large corporate or governmental organizations.38 These institutions were thought inevitably to have interests that would compete with the extra-market, ethical orientations through which professional ideologies justified claims to autonomy. The PMC's ethical commitments — the values and obligations that purport to define professional labor — must compete with realities of salaried work within an organization. As Stanley Aronowitz argues, "The bureaucratization of the professions corresponds to the rise of the corporations": in corporate and government bureaucracies, professionals "have been able to aspire to the position of middle management" which "constitutes the starting point of their identification with the company."39 That identification threatens not only an effective political alliance with a traditional proletarian class — among Aronowitz's and the Ehrenreichs' concerns — but also the extra-market commitments that are supposed to be the primary source of professional ethics.

Amateurs: "I just read books"

Condor's amateurism is positioned in contradistinction to these figures. Joubert's initial description suggests Condor is an amateur due to his lack of knowledge of the operational details of intelligence work — and certainly as a researcher he is well out of his area once he enters the field. Yet the film encourages us to imagine this amateurism in broader terms. From the beginning, Three Days of the Condor emphasizes Condor's incompatibility with the CIA. He is consistently late to work, plays practical jokes with security, violates protocols by using unauthorized entrances and exits, and, when asked by his superior Dr. Lappe if he is "entirely happy" at the CIA, responds: "It bothers me that I can't tell people what I do ... I actually trust a few people. It's a problem." Riding a mechanized bicycle through midtown New York traffic, sporting longish hair, blue jeans, and a tweed jacket, and consistently dismissive of Dr. Lappe's authority, Condor is coded as, if not explicitly countercultural, at least congenial towards the latter's revolt against technocracy (Fig. 3). In 1964, Jacques Ellul argued that the technological society "requires predictability and, no less, exactness of prediction. It is necessary, then, that technique prevail over the human being ... The individual must be fashioned by techniques."40 Condor's inability to arrive on time, mocking description of trust as "a problem," and disinclination "to go through channels" — as Dr. Lappe complains — suggests his refusal to be interpellated within the CIA's occupational culture, to be "fashioned by techniques."

Fig. 3 Countercultural coding

His lack of compatibility extends to the purported content of his labor. Though the CIA front at which Condor works is called the American Literary Historical Society (ALHS) and suggests the work of academics of the type that staffed the OSS during World War II, the omnipresence of communications and computational technologies in the mise en scène argues against the ALHS's use of hermeneutic analyses. As we have seen, these technologies dominate the first shots of the opening credits and, in Fredric Jameson's observation, "continue to affirm their mechanical existence and to go on producing 'text' in a haunting sonorous surcharge" even after their human operators are killed.41 How ALHS employees use this technology is a subject of discussion early in the film. Literary studies in the 1970s would not have been particularly dependent upon new technologies, though when we overhear Condor's coworkers debating a plot point from a detective novel — the killer's use of an "ice bullet" that melts and disappears, as in the Dick Tracy comics — it sounds conceivably like textual analysis. In fact, his colleagues are debating the best way to enter that fictional detail into a computer. "You're missing the point," Condor's colleague Janice (Tina Chen) argues: "The machine's just going to come back with 'Rephrase' or 'Express in other words.'" The implied need to encode plot details into previously established terminology suggests that whatever Condor and his colleagues are doing at the ALHS, it is not literary interpretation in the traditional senses of the term. While Condor has a tinkerer's facility with the technology — to Dr. Lappe's irritation he takes time during the day to repair one — he displays no affection for its use and procrastinates getting a "book on the computer by four" as instructed.

It is important to note that Condor's positioning as a quasi-countercultural figure amid a governmental technocracy is original to the film. In James Grady's novel Six Days of the Condor, on which the film was based, Condor's background is explicitly academic. He arrives at the CIA after failing a master's examination in graduate school; faced with nothing to say about Don Quixote, he wrote instead on Rex Stout's Nero Wolfe detective novels and his advisor sent him to lunch with a CIA recruiter.42 The film changes Condor's backstory, substituting graduate-level work in literary analysis with a history that emphasizes communication engineering skills. Higgins reports on Condor's employment history: "Two years' military service, Signal core. Telephone line and long line, switchboard maintenance. Six months overseas. Separated 9-61. Worked at Bell Labs: communications research. College on the GI Bill." Yet despite this technical background, Higgins emphasizes Condor's hermeneutic skills. When asked how someone unschooled in covert action could evade capture, Higgins explains: "He reads. He reads everything" (vocal emphasis in original). As Condor later elaborates to Kathy, "I just read books ... everything that's published in the world. And we feed the plots, dirty tricks, codes, into a computer. And the computer checks against actual CIA plans and operations. I look for leaks, I look for new ideas. We read adventures and novels and journals. Who'd invent a job like that?"

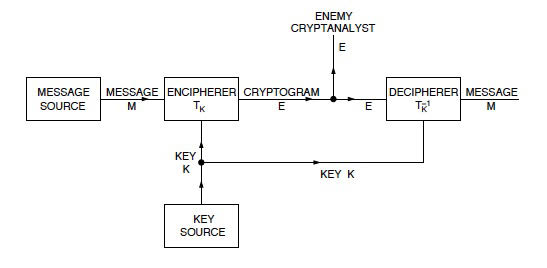

Claude Shannon might have, had he been in the spy novel business. Though Condor is first described by Mr. Wabash as a "reader researcher," the changes to Condor's employment history suggests that the work of the ALHS is less hermeneutical than computational and gestures towards an important evolution in intelligence practice over the course of the Cold War.43 It links Condor's search for "plots, dirty tricks, [and] codes" in published works to Claude Shannon's theorizations of cryptographic and communications systems while working at Bell in the 1940s. As Shannon himself observed, "From the point of view of the analyst, a secrecy system is almost identical with a noisy communication system" and the schematic diagrams he produced for each reveal the similarities (Figs. 1 & 4).44 Both imagine the obfuscation of a signal by distorting material — deliberately, in the encipherment of the cryptographer (in Shannon's case) or the extraneous details, characters, and plots of a detective novel (in Condor's), or randomly, in the static and interference endemic to a transmission channel (in the engineer's). The papers that built off these diagrams, Shannon's "Communication Theory of Secrecy Systems" (1945) and, more crucially for our purposes, "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" (1948), had a profound influence on fields from engineering and mathematics to cognitive science and DNA research and helped create the information age.

Fig. 4 Shannon's schematic diagram of a secrecy system from "Communication Theory of Secrecy Systems"

These papers also suggest why Condor might conceivably be considered an amateur. Despite his history at Bell Laboratories and his facility with telephone systems — he twice manipulates telephone switchboards to obtain information and communicate untraceably with Higgins — Condor evidences a strong commitment to a very different notion of decoding or "reading," which suggests he has not been fully assimilated into the CIA's evolving modes of operation. As we will see below, Condor's fealty to older, hermeneutic modes of analysis are part of what marks him as outside the community of intelligence professionals and uninterpellated by its techniques. Since Shannon's theories are dense, I focus only on three aspects of the theory that are relevant to Three Days of the Condor: first, the definition of noise as the unpredictable element in a system; second, Shannon's divorcement of a message's semantic content from its informational content; and finally, his recognition that predictability and redundancy are central to the proper coding of a message to defeat noise in the channel.

Predictability: "A picture that isn't like me"

The engineering goals of "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" are foregrounded in Shannon's opening paragraph, in which he observes that "the fundamental problem of communication is reproducing at one point either exactly or approximately a message selected at another point."45 The schematic diagram cited above (Fig. 1) may account for something as simple as a conversation in a loud restaurant — your mind (source) produces a thought that is articulated in the vocal apparatus (transmitter) and sent as sound waves (signal) through the air (channel) full of competing voices (noise) to the ear (receiver) and mind (destination) of your listener — or as complicated as the way DNA communicates with a protein chain. But the goal remains the same: to use a transmitter and receiver to encode/decode a message into a signal for the most effective transmission along a particular channel. Shannon recognized that these messages "have meaning; that is, they refer to or are correlated according to some system with certain physical or conceptual entities" but "these semantic aspects of communication are irrelevant to the engineering problem."46 That irrelevance is crucial. Communications technologies — for example, a telephone or telegraph system — are constructed to encode, transmit, and decode a message but not to comprehend it. A system must be able to transmit anything that that the set makes possible — sensible, nonsensical, long, or short. Removing questions of meaning is the first step in abstracting any individual message into a quantifiable entity. Messages as varied as a plan to seize Mideast oil fields or the plot of a novel all need to be reformulated as an objective, specifiable article expressed through a consistent unit of measure. That entity (expressed as binary digits, or bits) Shannon termed "information."

The process through which Shannon produced such an abstracted, quantified information are complicated (and superficially addressed in the following endnote), but ultimately his theory turns upon the predictability that is an inevitable part of language.47 Using language requires working within a system that is structured around difference and probability. Rules of usage shape and guide our choices: in English, "E" is the most common letter, a "Q" is inevitably followed by a "U," and so on; what speakers experience as a remarkable freedom to communicate is significantly restricted, and, as Shannon proved, renders our linguistic choices highly predictable. (Of course, this is what also makes them comprehensible. With no rules, everyone would be communicating in a language of one.) Because those choices vary in predictability, they carry more or less information as a result. After all, the "U" that follows a "Q" provides very little new information to a reader. It might easily be left out without fundamentally affecting the message. We can easily communicate with fewer symbols than are required by proper English, as Shannon's most famous example of redundancy demonstrates: "'MST PPL HV LTTL DFFCLTY N RDNG THS SNTNC'" — as heavy texters and the owners of vanity license plates will attest.48 Estimating the overall redundancy of English at approximately fifty percent, Shannon realized that the redundancy of any individual message might be manipulated to produce more favorable outcomes for a signal.49 For example, if a message must travel more quickly, the redundancy can be reduced while ensuring that the signal be decipherable once it arrives.

As importantly, redundancy can also be increased to defeat noise. Faced with a noisy channel, a signal risks being disrupted during transmission. A blast of static on the telegraph line might distort individual symbols and prevent the full signal from reaching the receiver. That noise is not predictable; the transmitter cannot know what part of a signal is likely to be affected. Shannon discovered that with proper coding, the redundancy of the signal can be increased to the point that losing one part will not damage a signal as a whole. Any potential damage can be compensated for preemptively.50 If redundancy can be decreased to improve the speed of transmission, it can also be increased to prevent damage to the message inflicted by noise. Proper coding can prevent the damage that any noise might do.

The technologies that receive "the plots, dirty tricks, [and] codes" Condor "feeds" them are presumably engaging in some sort of pattern analysis or deciphering operations — the film provides no specifics — but whatever the machines are doing, the semantic content is inevitably beside the point. Information technology in the 1970s could encipher and decipher, locate patterns and transmit information, but it could not understand significance. As N. Katherine Hayles explains, Shannon's discoveries enabled "technology that can transmit information in increasing amounts and with increasing accuracy but at the expense of having nothing to say about what the information means."51 By comparison, Condor, highlighting material from a text presumably for computer entry (Fig. 5), cannot help but understand the semantic content of those texts while he works "to get the book on the computer by four." What the computer apprehends as non-semantic, quantified information, Condor understands as knowledge: semantically rich, contextually informed, and open to application to a number of situations. That knowledge — as opposed to a quantified notion of information — inadvertently becomes part of the set on which he can draw while running from Joubert and the CIA. In a prototypical example, Condor finds a key that he brings to a locksmith to determine "the code number cut in the edge" that identifies the hotel. Suspicious of Condor's insider's knowledge, the locksmith asks, "Are you in the trade?" Condor explains: "I read about it in a story." For the computer, a random detail about identifying hotel keys might well be extraneous material or even a part of a "secrecy system" deliberately obscuring a signal. It would need to be dismissed for the signal to emerge. For Condor, however, that detail is knowledge understood, retained, and put to use through application to new circumstances. Though he is an amateur — someone who "doesn't know what to do" in professional spy craft — he can utilize details from a story that for technology would just be noise.

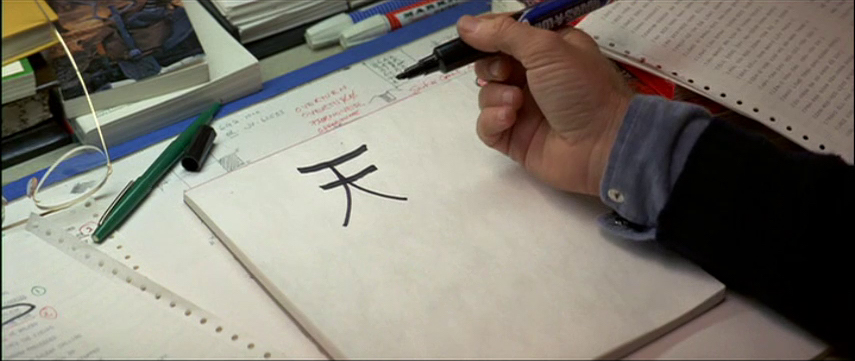

In a more telling instance, we see Condor working with a Chinese ideogram that appeared in "a mystery that didn't sell [but] has been translated into a very odd assortment of languages. Turkish, but not French. Arabic, but not Russian or German. Dutch" (Fig. 6). He asks Janice, who is Chinese-American, what it signifies, and she translates, "Tian. It means heaven." Condor presses for additional meanings and she jokes about her heritage, commenting: "Look at this face. Could I be wrong about an ideogram?" Condor answers, "It's a great face. But it's never been to China." The moment goes beyond the instance with the locksmith to elaborate Condor's approach to interpretation. He seeks to move past the purely denotative aspects of the ideogram, what Roland Barthes calls literal or "first order" meanings, to its connotations: the collection of second-order signifieds that have "a very close communication with culture, knowledge, history ... [I]t is through them, so to speak, that the environmental world invades the system."52 "The codes of connotations," Barthes explains, are "neither 'natural' nor 'artificial' but historical, or if it be preferred, 'cultural.'"53 Through connotations, we see the impact on a semiotic system of its use, the ways in which second-order associations adhere to the signifier and become "the common domain ... of ideology."54 Both contingent and context-dependent — a product of "culture, knowledge, history" — connotations are inaccessible to someone with Janice's lack of experience with contemporary China, regardless of her heritage.

Fig. 5 Non-semantic, quantified information or knowledge?

Fig. 6 Denotative or connotative meanings?

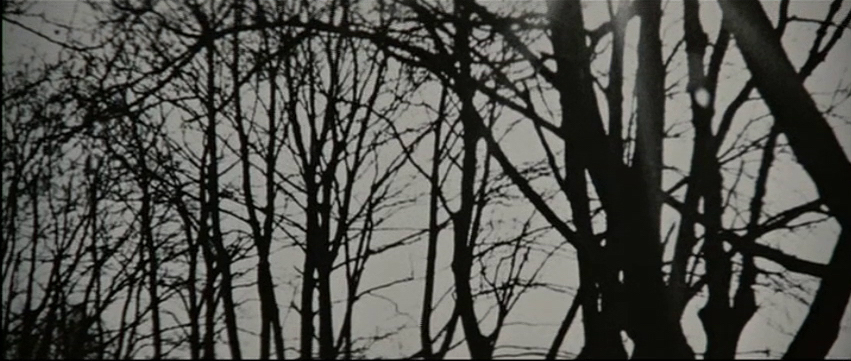

Condor's attempt to interpret the ideogram is one of two moments in the film in which he engages explicitly with semantic signs. While the former introduces the importance of history and cultural specificity to a sign's understanding, the latter shows the centrality of embedded, contingent connotative meanings to his success against the CIA. The second type of signs Condor reads are photographs — signs that Barthes himself grouped with ideograms as similar through their analogic relation between signifier and signified.55 Running from a second assassination attempt, Condor kidnaps at gunpoint a woman named Kathy (Faye Dunaway) so he can hide out in her apartment and secure some "safe quiet time to pull things together." While waiting for the television news, he notices a series of photographs hanging on the walls. The camera slowly pans across the images: an empty bench, a soccer goal with the net cut out, a path through the woods at dusk, and so on. "Lonely pictures," he comments. "You're funny. You take pictures of empty streets and trees with no leaves on them." When she responds, "It's winter," Condor corrects her: "Not quite winter. They look like ... November. Not autumn, not winter. In-between. I like them." Explaining to a photographer the content of her own photographs is obnoxious, but through this interpretation, Condor establishes himself as trustworthy, someone, as Kathy describes later, "with good eyes. Not kind. But they don't lie, and they don't look away much." More importantly, the moment extends and deepens Three Days of the Condor's investment in the idea of meaning as not only one of Condor's most effective tools against the CIA but also the film's most substantive critique of the technocracy's insistence that everything could be "purely technical, the subject of professional attention."56

In "The Photographic Message," Barthes argues that photographs constitute fundamentally different types of messages than linguistic signs.57 Appropriating Shannon's lexicon, he notes that a photograph "is formed by a source of emission, a channel of transmission and a point of reception" but unlike a written message, the photographic message, he claims, is a "message without a code"58:

From the object to its image there is of course a reduction — in proportion, perspective, colour — but at no time is this reduction a transformation (in the mathematical sense of the term). In order to move from the reality to its photograph it is in no way necessary to divide up this reality into units and to constitute these units as signs, substantially different from the object they communicate; there is no necessity to set up a relay, that is to say a code, between the object and its image.59

Barthes refers here to what Charles Sanders Peirce would describe as a photograph's indexicality; the ways in which the photographic image is analogically connected to the material it reproduces. Other semiotic systems produce their subject as a signified in relation to a signifier to construct a sign — for example, the concept "trees with no leaves" is related to the collection of letters and spaces that make up the phrase "trees with no leaves" in the case of writing — but a photographic sign requires no mediating symbols (letters, words) that intervene between the image and its source. Instead the image, or "emission," is "the perfect analogon" of the reality it captures: a photograph of an empty bench denotes that specific empty bench in reality; a photograph of trees with no leaves denotes those actual trees with no leaves (Figs. 7 & 8).60 It appears to present the thing itself, without additional and extraneous commentary.

Fig. 7 "A message without a code"

Fig. 8 "Lonely pictures"

Yet because the relation of signifiers to signifieds is "one of 'recording,'" the photographic sign is also highly contingent and inevitably includes supplementary material along with its subject, material that the camera cannot help but record regardless of a photographer's intentions. Barthes explains this observation by way of a comparison: a drawing of an empty bench is also an analogical reproduction, but a drawing "immediately necessitates a certain division between the significant and the insignificant: the drawing does not reproduce everything (often it reproduces very little), without its ceasing, however, to be a strong message." By comparison, "the photograph," Barthes explains, "although it can choose its subject, its point of view and its angle, cannot intervene within the object (except by trick effects)."61 Someone sketching the bench Kathy photographed might choose to leave out the weed growing up to the edge of the seat or the slat broken at one end, but Kathy herself cannot adjust or exclude these materials from her photograph.62 The camera records everything in front of its lens: there are aspects of the photographic image that the photographer can control, and there are aspects that she cannot.

There are a few points to observe here. First, the absence of a code does not preclude the possibility of connotations — in fact, it is precisely the connotations of Kathy's photographs that Condor reads when he describes them as "Lonely pictures." "The photographic paradox" that Barthes describes is "clearly not the collusion of a denoted message and a connoted message"; rather it is that "here the connoted (or coded) message develops on the basis of a message without a code."63 Barthes argues these connotations are found in the framing, posing of the figures, objects captured, photogenia (lighting, exposure, etc.), and aestheticism of the photograph. They are signs "endowed with certain meanings by virtue of the practice of a certain society: the link between signifier and signified remains if not unmotivated, at least entirely historical."64 While in the United States during the 1970s a black and white photograph of an empty park bench in November connotes loneliness, in another cultural context it might connote something else.

Second, Three Days of the Condor makes clear that the connotations that Condor interprets in Kathy's photographs are not necessarily intended — they may or may not be — but regardless, within the logic of the film, they are available to be interpreted. When Condor describes Kathy's photographs to her ("Lonely pictures ... Not quite winter. They look like ... November. Not autumn, not winter. In-between"), she first responds only with "Thanks." Later she elaborates on her photographic process, explaining, "Sometimes I take a picture that isn't like me. But I took it, so it is like me. It has to be." She refers here to the unpredictable element that Barthes identifies as central to photography: Kathy might set out to take one picture and end up with a different one, one that she does not recognize. The contingency of the photographic image means that you cannot always predict what the image will contain. To use Shannon's terminology, Kathy's intended signal might be contaminated by noise. Yet in of Three Days of the Condor, the noise, the unpredictable material, is counterintuitively able to be telling of who Kathy is.

In Camera Lucida, published approximately fifteen years after the two essays discussed here, Barthes termed the accidental or random effects of photography the punctum. In comparison to the studium, which is the subject the photographer intended to capture in the image, the punctum "is that accident [in the image] which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me)."65 If the studium is the viewer's "encounter [with] the photographer's intentions," the punctum is a contingent "co-presence" that "'happened to be there'" — the weed growing by the bench — and is captured accidentally or indifferently; a "supplement" that "occurs in the field of the photographed thing" and is "at once inevitable and delightful."66 The punctum is what Barthes enjoys about photographs: as Walter Benn Michaels explains, "The 'inevitable and delightful' detail 'does not necessarily attest to the photographer's art; it says only that the photographer was there, or else, still more simply, that he could not not photograph the partial object at the same time as the total object...'"67 Yet despite being inevitable, it is not predictable; its inevitability stems from the fact that a camera cannot help but capture additional material along with intended material, but one cannot necessarily know ahead of time what that additional material will be. Among other things, if it could be predicted, then it would become part of the photographer's intention — which is to say, part of the studium. The punctum thus functions like static in a noisy channel: you know there might be something but cannot predict what or where. This unpredictability complicates attributions of meaning to photographs: can there be meaning when aspects of a photograph are unintended? When there are, as Patrick Maynard observes, "'effects in successful photographs that one does not know how to attribute?'"68 How is one supposed to interpret the random, the unpredictable, the noise? To understand it as meaningful? But for Kathy, "a picture that isn't like me" — that is unintended — is still able to communicate something fundamental about herself. It has meaning; it is available to be read.

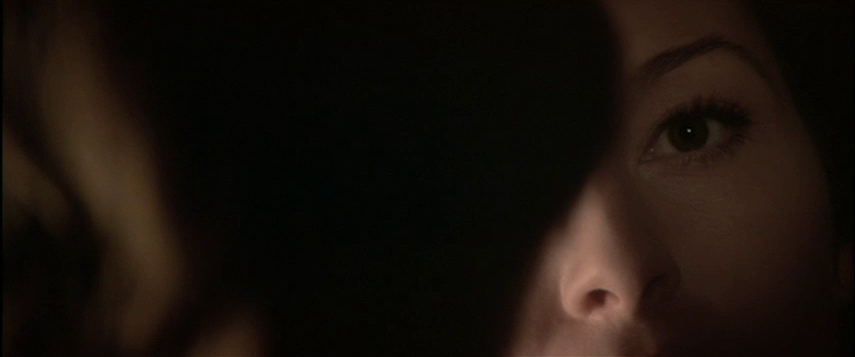

Condor's ability to read those unintended and unpredictable elements becomes a crucial point of connection between the two of them. Barthes observes that "photographic connotation, like every well-structured signification, is an institutional activity; in relation to society overall, its function is to integrate man, to reassure him."69 Connotative meanings knit the spectator into a social or cultural fabric; they provide a point of connection and shared understanding that marks one's belonging to a culture, a historical moment, a community. Kathy is reassured by what Condor sees her in photographs and by her own extension what he sees in her. Their subsequent sexual intimacy — even though she's been kidnapped at gunpoint — is shown through a montage sequence in which shots of their entwined bodies are overlaid with shots of the photographs and an image of her eye is juxtaposed with her camera's lens (Figs. 9 & 10). This montage foregrounds the camera's role in bringing them together, but it also suggests those things that humans can do but cameras, transmitters, receivers, and computers cannot: read, interpret, understand, and connect.

Fig. 9 Kathy's eye ...

Fig. 10 ... juxtaposed against the camera's lens

Ethics: "I told them a story"

Kathy's assistance is crucial to Condor's ability to expose the rogue element in the CIA. She provides safe harbor, strategizes approaches, helps Condor interrogate Higgins, and aids his travel to Washington, D.C. Once there, Condor corners Atwood at his house in suburban D.C., and demands with bafflement: "Who are you? Who are you?" But it is his third question that matters: "What do you do for a living?" It suggests that the former question can only be understood through reference to the latter. Learning that Atwood is Deputy Director for Operations, Condor demands, "What does operations care about a bunch of goddamn books?" and then performs a hermeneutic leap that technology presumably could not make: "A book in Dutch. A book out of Venezuela. Mystery stories in Arabic. What the hell is so important about ... Oil fields. That's it, isn't it? This whole damn thing was about oil." Assassinated by Joubert soon thereafter, Atwood provides no responding account of his actions. Our only explanation is Higgins's defensive description of the service at the end of the film: "We play games. What if? How many men? What would it take? ... That's what we're paid to do." Anticipating the needs of politicians and policymakers, running scenarios and predicting outcomes, as here described the job of intelligence professional perfectly embodies the technocracy's demand for predictability. Though Atwood knew the oversight committee "would never authorize it," he "took it all too seriously" and forgot that, as Sherman Kent puts it, a CIA professional's job is "the exploration of alternative solutions" but not their implementation.70 That is, Atwood commits the "post-Watergate" crime of exceeding his operational brief and then fumbling the cover-up. He presumed an agency that he did not possess and murdered Condor's colleagues at the ALHS.

This final encounter with Higgins is important to establishing the film's ethical position. At the beginning, Higgins is aligned with Condor in his commitment to uncovering illegal operations and explicitly scorns Atwood's unsanctioned activities. At the end, Higgins does not balk at hiring Joubert himself to murder Atwood — recommitting Atwood's original crime — because, Joubert speculates, Atwood was about "to become an embarrassment." Higgins is motivated to do so; the film implies that a willingness to contract assassination is a price of CIA advancement. After Condor notifies Higgins that Atwood is the murderer, the following conversation takes place between Higgins and Wabash:

Wabash: Why aren't you further along, Mr. Higgins?

Higgins: You mean in the Company, sir?

Wabash: You seem perfect for it. Are you perfect for it, Mr. Higgins?

Higgins: I've tried to be, sir.

Wabash: Were you recruited out of school?

Higgins: No sir. The company interviewed a few of us in Korea. You served with Colonel Donovan in the OSS, didn't you sir?

Wabash: I sailed the Adriatic with a movie star at the helm. It didn't seem like much of a war, now, but it was. I go even further back than that. Ten years after the Great War, as we used to call it. Before we knew enough to number them.

Higgins: Do you miss that kind of action, sir?

Wabash: No. I miss that kind of clarity. Mr. Higgins: you do understand the Company's position? There's nothing in the way of your doing this, is there?

The exchange emphasizes Higgins's occupational frustrations — "Why aren't you further along, Mr. Higgins?" — and thwarted ambitions — "I've tried to be, sir"—and explicitly references the CIA's efforts to professionalize the service through recruitment at liberal arts universities. In so doing, it implicitly nods to the resentment felt by those employees who might have traveled alternate routes to the intelligence services — the Army — and whose subsequent career paths might be stymied as a result.71) Higgins's curiosity about OSS mythology provides the film a chance to remark on the distance traveled between the wartime Adriatic and Cold War realpolitik — a familiar gesture of national self-examination in the years after the Vietnam War.72 But this romanticization of the World War II service fails fully to obfuscate the fact that Wabash is telling-without-telling Higgins to contract Atwood's death and implying his occupational advancement is dependent on the result.

Atwood's actions are thus figured not through the individuated motives of a single character but the methodologies of a professional institution ("We play games") that takes for granted a right to murder U.S. citizens in order to secure unlimited oil reserves for an ill-defined future. As Roszak expresses the logic of technocracy: "Wherever non-human elements ... assume greater importance than human life and well-being ...the way is open for the self-righteous use of others as mere objects."73 In keeping with his earlier techniques, Condor utilizes older communications technologies to counter those "games." Horrified by the CIA's disregard for human life — "Boy, have you found a home. Seven people killed! ... And you play fucking games!" — Condor tells Higgins that he has given his information to The New York Times, betting that national outrage over CIA operations will ensure justice for his colleagues' deaths and protect him from further attempts at assassination. "You play games," he tells Higgins, "I told them a story." The difference between playing a game and telling a story is an extenuation of the difference between the professional and the amateur: the difference between a limited choice within an established structure — a "move" — and an unlimited choice that constructs a new one, between an opportunity to establish mastery and an opportunity to create meaning. As Condor walks off, Higgins demands: "How do you know they'll print it?" The movie does not answer this question, though Nixon-era journalistic successes from the Pentagon Papers to Watergate suggest sources for Condor's optimism. Yet the credits run over a freeze-frame that fades to a black and white image of Condor's lonely face as he disappears into the New York crowds (Fig. 11). The presence of Salvation Army carolers suggests its late November or early December — "not autumn, not winter. In-between."

Fig. 11 "Not autumn, not winter. In-between."

The film thus concludes ambiguously on a photographic image similar to one of Kathy's, inviting us to engage in the same hermeneutic processes as Condor, and ultimately "to integrate" and "reassure" ourselves with our fellow interpreters through shared meanings.74 In a post-Watergate United States, we are encouraged to find meaning in Condor's story, to decode its "serious ideas" and, presumably, advocate for change. But for our purposes, the final encounter with Joubert at Atwood's house provides the more interesting conclusion. As they leave Atwood's body behind, Joubert asks: "Tell me about the girl ... She was chosen, how? By age? Her car? Her appearance?" Condor's response — "Random. Chance." — surprises Joubert but fits with the film's overall investment in unpredictability. The unintended details that mean in the photograph, like the amateur amid the professionals, like the noise in the channel, and like the choice of Kathy herself, are unpredictable and in that unpredictability lies Condor's success.

Yet upon discovering Condor and Atwood in Atwood's study, Joubert comments: "You were quite good, Condor. Until this. This move was predictable." Condor has started, in Jacques Ellul's phrase, to be "fashioned by techniques."75 Exposure to technocratic systems will professionalize you despite yourself, and Condor's interpellation is nearly complete. Joubert quickly reassures Condor that no longer means him harm. "I have no arrangement with the Company concerning you," he explains: "They didn't know you'd be here. I knew that you'd be here." Since Atwood is dead, the contract for Condor's assassination is void. But when Condor tells Joubert that he hopes to return to New York, Joubert offers a final prediction:

"You have not much future there. It will happen this way. You may be walking. Maybe the first sunny day of the spring. And a car will slow beside you. And a door will open. And someone you know, maybe even trust, will get out of the car. And he will smile a becoming smile. But he will leave open the door of the car. And offer to give you a lift."

Joubert's power to predict events is validated when the events described in the scene above occur: though it's November, not spring, Condor's final conversation with Higgins begins with a hail from a car to the sidewalk just as Joubert describes. Count Condor lucky to have been forewarned. When Condor asks, "You seem to understand it all so well. What would you suggest?" Joubert recommends Europe and remarks: "What I do is not a bad occupation. Someone is always willing to pay." Is he recruiting Condor to a career as a contract assassin? The idea is less far-fetched than it first appears. In the film's original binary of amateurs and professionals, Condor and Joubert are placed in opposition. But this scene reorganizes the relevant positions. No longer contrasting amateurs and professionals, the film now opposes institutions and those who affiliate with them against the individuals who do not. Condor and Joubert — amateur and specifically expert professional — are united in their rejection of institutional affiliation and now positioned in opposition to Atwood and Higgins, who are well-past what Stanley Aronowitz describes as "the starting point of [the professional's] identification with the company."76

Reshuffling the relevant binaries, the film thus suggests the ways in which amateurs and expert professionals are similar and, by extension, the ways in which Condor and Joubert have been aligned all along. Both operate outside the routines of institutional procedures, the former because he never bothered to learn them and the latter because his superior specialization and expertise allowed him to cut those ties when they grew burdensome, operating above such concerns as agency, nation, or cause. This freedom is what renders them effective. They even share the beginning of an ethic; as Pollack observed above, "The von Sydow character is an honest bad guy, which I prefer any day to a lying good guy."77 Given a choice between someone who murders for money versus someone who murders for an institution, it seems we should choose the one that's honest.

Or not entirely — Condor does not take Joubert up on his offer. He declines, explaining "I was born in the United States, Joubert. I miss it when I'm away too long." His ties even to a "post-Watergate America" are not entirely gone. But Three Days of the Condor's temporary flirtation with Condor's recruitment suggests not only the alignment of his and Joubert's anti-institutional biases — their shared conviction that PMC laborers are inevitably "liars, finks [or] mystifiers ... coopted and corrupted by the System" — but also the value of amateurist discourse to a professionalizing industry such as Hollywood and in the changing professional landscape that Brint describes. As economic factors reduced "the influence of the traditional ethical and cultural legitimations of professionalism," as Brint argues, amateurist discourses made that reduction acceptable because the institutions in which those ethics might have been put to use were viewed as irretrievably tarnished.78 The outraged ethics of the amateur thus justify the expert professional's relinquishment of institutional ties and rationalize the separation of his labor from institutions and organizations. Condor's paralyzed outrage renders it acceptable — indeed, makes it sound like an opportunity — that the expert professional's beliefs are limited to his "own precision," as Joubert says. If institutions are inevitably "coopted and corrupted," the professional is better off unaffiliated with them. However, the cost is a loss of any influence over institutional operations and abandonment of the very values that justified professional autonomy in the first place. And while the film rejects this conclusion through its turn to The New York Times and the implied democratic control of government institutions, this final alignment of amateurs and professionals against those institutions is in fact the film's most salient prediction.

Abigail Cheever is Associate Professor of English and Film Studies at the University of Richmond and the author of Real Phonies: Cultures of Authenticity in Post-World War II America. Her current book project investigates the concept of professionalism and professionalization in New Hollywood-era filmmaking and American film cultures of the 1960s-1980s.

References

I benefited enormously from conversations with Ted Bunn, Beth Crawford, Deak Nabers, and Ashley Silverburg while working through Shannon's "A Mathematical Theory of Communication." Many thanks are owed for their engaging explanations. Beth Crawford, Sean McCann, Palmer Rampell, Monika Siebert, and the participants in Post45's 2016 Conference provided valuable suggestions and advice at various stages of this project. I am grateful for their considerable assistance."

- Three Days of the Condor, dir. by Sydney Pollack (1975; Hollywood: Paramount DVD, 1999), DVD.[⤒]

- Bernard Bledstein, The Culture of Professionalism: The Middle Class and the Development of Higher Education in America (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1976), 88.[⤒]

- Michael Denning, Cover Stories: Narrative and Ideology in the British Spy Thriller (London and New York: Routledge Revivals, 2014), 117.[⤒]

- Patrick McGilligan, "Hollywood Uncovers the CIA," Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media 10-11 (1976): 11-12. http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/onlinessays/JC10-11folder/PollackMcGilligan.html.[⤒]

- The term professional-managerial class was first coined by Barbara Ehrenreich and John Ehrenreich in 1977 as part of the so-called New Class debates ("The Professional Managerial Class," in Between Labor and Capital, ed. Pat Walker [Boston, MA: South End Press, 1979], 5-45). But interest in labor dependent upon secular formal knowledge, its impact on class, culture, and democracy, and its putative decline in the era of the corporation, arguably increased in the 1960s and 70s with the appearance of both academic and trade publications by Stanley Aronowitz, Daniel Bell, Burton J. Bledstein, Harold Braverman, Eliot Freidson, Alvin Gouldner, Jacques Ellul, Margali Sarfatti Larson, Christopher Lasch and Theodore Roszak. For a useful summary of the central sociological debates surrounding the professions and the PMC more broadly see Eliot Freidson, Professional Powers: A Study of the Institutionalization of Formal Knowledge (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1986).[⤒]

- Alvin Gouldner, The Future of Intellectuals and the Rise of the New Class (New York: Palgrave, 1979), 19.[⤒]

- Paul Goodman, The New Reformation: Notes of a Neolithic Conservative (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2010), 70. These comments originally appeared in a September 1969 issue of the New York Times Magazine. Goodman describes student hostility specifically towards the professional class, arguing that in the twentieth century "science and technology have been the only generally credited systems of explanation and problem-solving"; but in the current moment, "they have come to seem to many, and to very many of the best of the young, essentially inhuman, abstract, regimenting, hand in glove with Power" (39). There is an often-observed irony here. In their analysis of the PMC, Barbara Ehrenreich and John Ehrenreich argue that the student activism of the 1960s — activism conducted by the very students whom Goodman references — itself had its roots in professional ideology. They note "student activists typically came from secure backgrounds, and were, compared to other students, especially well-imbued with the traditional PMC values of intellectual autonomy and public service," and their efforts represented an attempt to "reassert the autonomy which the PMC had long since ceded to the capitalist class" (31). By the late 1960s, however, students' challenges to the status quo, which originally appeared symptoms of the PMC's "rising confidence," had morphed into "a kind of negative class consciousness" in which the possibility of "autonomy—objectivity, commitment to public service, and expertise itself" was called into question (31, 39). Co-optation and corruption were no longer personal failings; they were the inevitable condition of the PMC worker in the era of late capitalism.[⤒]

- Theodore Roszak, The Making of a Counter Culture: Reflections on the Technocratic Society and its Youthful Opposition (1968; Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 5.[⤒]

- Jerome Christensen, America's Corporate Art: Studio Authorship of Hollywood Motion Pictures (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011); J.D. Connor The Studios after the Studios: Neoclassical Hollywood (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015); Jeff Menne, Post-Fordist Cinema: Hollywood Auteurs and the Corporate Counterculture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019); Derek Nystrom, Hard Hats, Rednecks, and Macho Men: Class in 1970s American Cinema (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).[⤒]

- Peter Biskind, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1999), 392, quoted in Connor, The Studios after the Studios, 1.[⤒]

- Connor, Studios, 99.[⤒]

- My analysis builds off of recent work by Bernard Dionysus Geoghegan, James Gleick, Ronald R. Kline, and Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman that demonstrates information theory's considerable influence on midcentury American culture. See Bernard Dionysus Geoghegan, "From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Lévi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus," Critical Inquiry 38, no. 1 (2011): 96-126; James Gleick, The Information: A History, A Theory, A Flood (New York: Vintage, 2012); Ronald R. Kline, The Cybernetic Moment: or Why We Call Our Age the Information Age (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017); Jimmy Soni and Rob Goodman, A Mind at Play: How Claude Shannon Invented the Information Age (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2017).[⤒]

- C.E. Shannon, "A Mathematical Theory of Communication" (1948) in The Mathematical Theory of Communication, ed. Claude Ellwood Shannon and Warren Weaver (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 29 - 125.[⤒]

- Geoghegan, "From Information Theory to French Theory," 114-15.[⤒]

- Kline, Cybernetic Moment, 3, 129. The optimism of this thinking was immediately tested at the inaugural Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation Conference on Cybernetics, at which "Norbert Wiener [the founding father of cybernetics in the United States] flatly stated that the social sciences did not have long enough runs of consistent data to which to apply his mathematical theory of prediction." By the 1948 conference, Mead and Bateson were reduced to negotiating for the number of linguists they might include, whom they then "coached" on how to make a "better showing" among the "physio-math boys" (Kline 37). Kline's study provides an extensive account of how the discourses of information theory and cybernetics affected diverse academic fields in the 1950s and 60s and helped shape our current "information age." As the above quote suggests, a recurring topic is how the rapid dissemination of both concepts inspired intermittent efforts at "boundary work" by scientists anxious to legitimize the discourse and limit its more speculative applications (104). Geoghegan also examines the intersection of cybernetics, information theory and the social sciences during the 1950s and early 60s. He argues this period saw the development of a "cybernetic apparatus" through which Jakobson and Lévi-Strauss "hailed the potential of recently developed media instruments and techniques to validate structural research and modernize the human sciences" and morphed "material instruments and techniques ... into ostensibly immaterial ideals that furnished researchers with procedures for investigations unhindered by historical, political, or disciplinary difference" (97-8). Geoghegan tracks the creation and dissemination of this apparatus through the Rockefeller Foundation's postwar efforts to support "expert-driven rational solutions to social and political problems," Jakobson's Rockefeller-inspired efforts to unite a range of scholars in applying information theory and cybernetics to linguistics and communications, Lévi-Strauss's creation of a CENIS-affiliated seminar on cybernetics in Paris in 1953, and both scholars' application of information theory- and cybernetic-inspired concepts to their work (102, 110).[⤒]

- Claude Shannon, "The Bandwagon," IRE Transations—Information Theory 2, no. 1 (1956): 3. By the mid-1960s, Geoghegan writes, "scientists' enthusiasm over cybernetics' universal claims transformed into embarrassment over its proponents' unchecked hubris," and information theory had "narrowed its ranks to engineers focused on specialized mathematical analysis" (123). In France, Jakobson's and Lévi-Strauss's "cybernetic structuralism" would become for philosophers such as Julia Kristeva, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, and Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari a central example of "scientists' efforts to pacify an unruly world with orderly models" (124).[⤒]

- Shannon, "Bandwagon," 3.[⤒]

- Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966), 18; Roland Barthes, "The Photographic Message" (1961) in Image-Music-Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill & Wang, 1977), 17, emphasis in original.[⤒]

- McGilligan, "Hollywood Uncovers the CIA," 10-11.[⤒]

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, tr. Richard Howard (New York: Hill & Wang, 2010): 42.[⤒]

- Fredric Jameson, The Geopolitical Aesthetic: Cinema and Space in the World System (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992), 11.[⤒]

- Ibid., 10.[⤒]

- Ibid., 13.[⤒]

- Roszak, The Making of a Counter Culture, 5-6.[⤒]

- Ibid., 7[⤒]

- The CIA has its origins in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), created by military order under President Roosevelt in 1942 and charged with the "collection and analysis of 'strategic information' and the planning and direction of 'special services'" (Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones, The CIA and American Democracy [New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989], 18). Though the OSS was disbanded in 1945, when President Truman created the CIA in 1947, many former OSS agents returned to service. Robin Winks provides a thorough account of the agency's early efforts at professionalization. Charting the links between academia — particularly Yale University — and the Agency, Winks recounts the Agency's claims to the professional status long held by academics, doctors and lawyers; further, he himself legitimates those claims though a repeated invocation of the objectivity, expertise, commitment, and ethos of service held by those who served in the Agency's early years. For example, he observes that CIA recruiters "went primarily to the private universities and colleges" — institutions that wouldn't "sink the creativity of their students in programs of vocational training" — because "the OSS knew that while it wanted skilled safecrackers, it also needed men and women able to recognize the value of the content of the safes once cracked" (Cloak and Gown: Scholars in the Secret War 1939-1961, 2nd ed. [New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996], 24). The image of a safecracker providing materials to a superior and highly trained intellect for analysis reflects the purported hierarchy between manual and mental labor on which professional ideology asserts its privilege. Winks's argument thus embodies professional ideologies even as it describes them and imitates the claims that professional organizations make to distinguish themselves from other occupations.[⤒]

- Sherman Kent, Strategic Intelligence for American World Policy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015),180. Kent himself was a historian at Yale University who was recruited to the Office of Strategic Services during World War II. On his return to intelligence work in 1950, Kent first served under William L. Langer at the Office of National Estimates (ONE) until 1952, and then succeeded Langer as Director of that Office until he retired in 1967. In 2000, the CIA established The Sherman Kent Center for Intelligence Analysis in his name, for "[I]f intelligence analysis as a profession has a founder, the honor belongs to Sherman Kent"; Jack Davis, "Sherman Kent and the Profession of Intelligence Analysis," The Sherman Kent Center for Intelligence Analysis, Occasional Papers 1, no. 5: (2007), last updated January 03, 2012. https://www.cia.gov/library/kent-center-occasional-papers/vol1no5.htm[⤒]

- Ibid., 201; Seymour M. Hersh, "Huge C.I.A. Operation Reported in U.S. Against Antiwar Forces, Other Dissidents in Nixon Years," New York Times, December 22, 1974. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/12/22/archives/huge-cia-operation-reported-in-u-s-against-antiwar-forces-other.html These disclosures inspired two Congressional investigative committees — the Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities (known as the Church Committee) and the House's Select Committee on Intelligence (the Pike Committee) — that brought such infamous operations as the CIA's involvement in Chile and various assassination programs before the nation. In Rhodi Jeffreys-Jones's phrase, by early 1975 "[i]ntelligence had taken over from Watergate as the stick with which to beat the allegedly power-mad White House" (Jeffreys-Jones, The CIA and American Democracy, 199). Among other results, their efforts produced the congressional standing committees on intelligence that oversee CIA activities.[⤒]

- See, for example, Alan Pakula's The Parallax View (1974), Sam Peckinpah's The Killer Elite (1975), John Schlesinger's Marathon Man (1976), and William Richert's Winter Kills (1979).[⤒]

- Bruce Robbins, Secular Vocations: Intellectuals, Professionalism, Culture (London and New York: Verso, 1993): 30.[⤒]

- Goodman, New Reformation, 30.[⤒]

- Steven Brint, In the Age of Experts: The Changing Role of Professionals in Politics and Public Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 40. I am grateful to Sean McCann for directing me to Brint's analysis of expert professionalism and its emergence in the 1960s and 1970s.[⤒]

- Brint, In the Age of Experts, 42.[⤒]

- Ibid., 204.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Jameson, The Geopolitical Aesthetic, 10.[⤒]

- Patricia Erens, "Sydney Pollack: The Way We Are" Film Comment 11.5 (1975): 25.[⤒]

- Ehrenreich and Ehrenreich, "The Professional-Managerial Class," 22.[⤒]

- Aronowitz, False Promises, 306. Barbara Ehrenreich and John Ehrenreich argue that "the deepest rift" within the professional-managerial class occurred "between the managers, administrators, and engineers on the one hand, and those in the liberal arts and service professions on the other," — or, more generally, between those working for corporate bureaucracies those working in academia or for state institutions. This rift based itself in a different "general political outlook: [t]he managerial/technical community came to pride itself on its 'hard-hardedness' and even on its indifference to the social consequences of its labor (i.e. its helplessness)" whereas the academics and service providers "became the only repository of the traditional PMC antagonism to capital." (Ibid., 28).[⤒]

- Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society, trans. John Wilkinson (New York: Vintage, 1964), 138.[⤒]

- Jameson, The Geopolitical Aesthetic, 13.[⤒]

- James Grady, Six Days of the Condor (New York: Mysterious Press/Open Road Integrated Media, 2016): 16-17.[⤒]

- Stephen Budiansky's Code Warriors: NSA's Codebreakers and the Secret Intelligence War against the Soviet Union (New York: Vintage, 2016) explores the rise in importance of signals intelligence over other forms — including open-source and human intelligence — in the postwar period, and the growing competition between the CIA and NSA over which agency would be given primary role in its interpretation.[⤒]