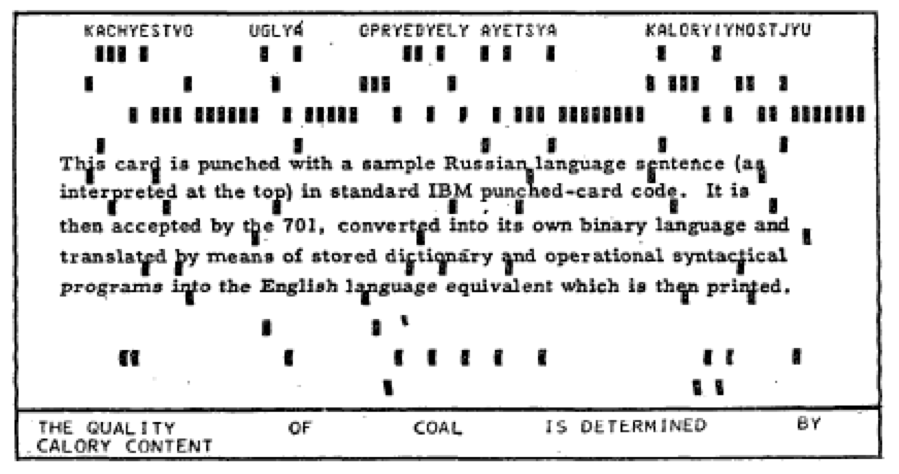

At the International Business Machines Corporation on January 7, 1954, a team of linguists and engineers from Georgetown University demonstrated the automatic translation of Russian into English with an IBM 701 digital machine. "Russian Is Turned Into English By a Fast Electronic Translator," the New York Times reported, calling the event "the first successful use of a machine to translate meaningful texts from one language to another."1 The Times article was accompanied by a sample punch card, blown up and featured on the front page, with a line of Russian on one side and the corresponding English translation on the other (Fig. 1). On computer punch cards, binary holes run vertically down the center, indicating the direction in which the card feeds into the machine. But to make the translated sentence legible for its readers, the Times printed the card horizontally, creating the illusion that the Russian words on top transformed into binary punches that then reassembled into an English translation on the bottom. The image conveyed the triumph of the event, described by the Times as the invention of a "mechanical model of language," the culmination of efforts to transpose human language into "a sequence of mathematical operations." The reporter pointed out that "a girl operator" who "did not know Russian" could feed the instructions to "an automatic digital computer."2 The "Georgetown event," as the 1954 demonstration came to be known, was widely understood to confirm the idea that translation was no different than mathematics, and that mathematics was itself the "language" of new machines.

Fig. 1. The punch card from the "Georgetown event," translates from Russian "THE QUALITY OF COAL IS DETERMINED BY CALORY CONTENT."

Just three years later, Russian émigré Vladimir Nabokov published a novel in which translation functions with decidedly less than mathematic precision, and in which translation emerges as crucially tied to gender, surfacing the questions that these "girl operators" inevitably raise. In Pnin, Russian language professor Timofey Pnin struggles to adjust his mother tongue to the masculinist communication channels — lecturing, teaching, administrating — through which academic information moves. Always engaged in the "complicated" "procedure" of making sense to his colleagues and students, Pnin "laboriously translate[s] his own Russian verbal flow . . . into patchy English."3 The breakdowns in this process entertain Pnin's colleagues when he hosts a party late in the novel. "His mispronounciations are mythopeic," one guest marvels. "His slips of the tongue are oracular. He calls my wife John" (165). The slippage from an original Russian "flow" to a "patchy English" output construes Pnin as a figure meant to oppose the idea of mechanical translation that IBM machines at the time promised. Though the guests are amused by, even enamored with, their Russian colleague's mistranslations, they express doubt about the future of Pnin's career. "The world wants a machine," says one guest, "not a Timofey" (161). Nabokov portrays his absent-minded professor as irrelevant in an age when machines do the work of translation. At the same time, however, linguistic errors provide the fodder for a poignant fictional characterization meant to endear readers to "poor Pnin." In sympathizing with a character identified by his "disarming old-fashioned charm" (10-11) and "uncontrollable smile" (13) — not to mention a name that sounds like "pain" — readers learn to love the Russian language professor who calls his house warming party a "house heating soiree" (151), and who laments, "I haf nofing left, nofing, nofing!" (61). From one point of view, Nabokov humanizes translation in Pnin by recuperating the process from the cold mechanics of the Georgetown demonstration and invigorating it with the allure of a fictional character described as "almost feminine" (7). And as for mathematics: "'Eighteen, 19,' muttered Pnin. 'There is not great difference!'" (75).

Nabokov counters the mechanical reduction of language with Pnin, a fictional character whose botched translations convey linguistic complexity. After all, Pnin's errors are a way for Nabokov to display his wit, to exercise his artistic control over the nuance of the English language in the moments Pnin is seen charmingly stumbling over it. Nabokov exploits the coincidences of translation — i.e. Pnin and pain — for aesthetic effect. In fact, it is precisely through his pain, what manifests as a "seizure," that Pnin experiences the human excess of his difficulties with language (25). Nabokov, moreover, conveys this experience as a form of literary reading. Early in the novel, Pnin associates the onset of a seizure with "past occasions of similar discomfort and despair," and especially with the wallpaper from his childhood bedroom (21). The intricate design of the wallpaper had lead young Pnin to search for its meaning, and he "persevered in the struggle" to immerse himself in its "difficulties" (24). Though the precise significance of the wallpaper continues to elude him, Pnin's efforts are rewarded when he experiences an unanticipated secondary effect:

The foliage and the flowers, with none of the intricacies of their warp disturbed, appeared to detach themselves in one undulating body from their pale-blue background which, in its turn, lost its papery flatness and dilated in depth till the spectator's heart almost burst in response to the expansion (24).

The impenetrability of the wallpaper overwhelms Pnin, and the "difficulty" gives way to euphoria. Thus, the passage allegorizes the reading of a literary text, from the bursting of the reader's heart to the "papery flatness" that such a vivid reality transcends.4 Pnin's state of suffering bears out the feeling evoked by the autonomy of a work of art, a feeling Nabokov famously referred to as "aesthetic bliss."5

In spite of this allegorized, aesthetic scene of reading, Nabokov also portrays Pnin as engaging in a form of reading that is formally mathematic. From his bed, the feverish Pnin observes that the design of flowers and branches on his wallpaper is divided into two "planes," that each plane features the "repetition" of "elements" in a "series" to convey the illusion of a "rational pattern"; however, the failure on young Pnin's part to identify "what system . . . governed . . . the recurrence of the pattern" renders the wallpaper illegible, its coherency made "meaningless" by its unreadability (23). Aesthetically pleasing, the "system" of "patterns" also constitutes a formula that refuses to be solved. Pnin's struggle stems from his inability to reconcile the random "reappearance" of symbols, their "repetition" "here and there," with a coherent "recurrence" that would indicate a significance that structures the design. Are the repeated symbols on his wall the result of a random coincidence or an intentional pattern? What if they are both? What would it mean for "aesthetic bliss" to synonymously implicate something formulaic? After all, the wallpaper's mathematics are also the source of Pnin's aesthetic revelation, his affective response to its insolubility.

I will return to the question of how gender is implicated in this blurring of aesthetics and mathematics. For now, I want to draw attention to how coincidence and repetition, as established in the description of the wallpaper, finds concentrated expression in the figure of Pnin's narrator, who describes himself as an "evil designer" of a "pattern" that haunts his protagonist, claiming he has "concealed the key of the pattern with such monstrous care" (23). The narrator's phrase, "the key of the pattern," raises the question of how Pnin's version of reading pertains to the act of deciphering a cryptogram, which begins with a linguistic key. The question is germane to Nabokov's cultural moment because of the work of U.S. chief cryptologist William F. Friedman, who proved mathematically that differentiating between random similarities and patterns of significant frequency enables the decoding of encrypted messages. In 1935, Friedman argued that the meaning of a message can be determined by "a purely mathematical analysis" that he called "the index of coincidence."6 By the 1950s, just when Nabokov was writing Pnin, Friedman's work helped motivate the construction of a mechanical model of language, including efforts in machine translation. Rereading Pnin in light of Friedman's influential work explains Nabokov's curious invention of a first-person omniscient narrator: when the narrator acts with the traditional objectivity of an omniscient narrator, the novel's coincidences look like the mere reporting of random phenomena — events as they truly happened; but when coincidences accrue, turning into patterns, they expose the narrator's conspicuous intentionality. Patterns indicate that events have been designed, not reported, for the purpose of storytelling. Furthermore, the combination of coincidences and patterns in Pnin signals to the reader, as it would a cryptographer, the possibility of decoding language for the purposes of narrative interpretation. Nabokov invents his first-person omniscient narrator, then, to construct a problem for the reader. To see through events as they are told and discover events as they happened requires a form of cryptographic reading that disambiguates coincidence from pattern. In what follows, I show that moments of cryptographic reading in Pnin present a narrative logic attuned to digital models of probability, and that these narrative moments clarify an increasing tendency towards self-reflexivity in the contemporary novel.7

To be certain, critical readers of Pnin have long undertaken methods of pattern recognition to understand the novel's narrator, occasionally using explicitly cryptographic terminology that appears encouraged by and perhaps even vital to the novel's formal problems.8 However, such cryptographic terms — patterns, cyphers, codes — have thus far been understood in Nabokov studies as mere metaphors. Through them, scholars reassert the aestheticism of Nabokov's modernist wordplay without acknowledging the historical conditions animating his language and, consequentially, the particular forces motivating his decision to tell the story of a language professor at a university campus. An ostensible "campus novel," Pnin emerges at the moment of the New Criticism's programmatic canonization of literary modernism and its prioritization of linguistic difficulty.9 Yet the degree to which these developments correspond with the simultaneous arrival of mathematical theories of language in American universities has been obscured by the same failure to recognize that Pnin's wallpaper displays a form of modernist difficulty also construed as cryptographic.10

The phenomenon of machine translation thus informs my interpretation of a problem that has long occupied readers of Pnin. At the same time, the novel's formal contextualization of machine translation enables us to see the remarkable ways in which cryptographic reading permeates midcentury linguistic practices. Midcentury literary culture and early digital innovations like machine translation are understood to have inhabited distinct domains. But in what follows, I read the founding documents of machine translation alongside those of the New Criticism to argue that mathematic models of language and traditional close reading both developed through applications of cryptography to language.11 Retracing this shared intellectual origin not only reveals Pnin's contribution to an ascendant postwar aesthetic unmistakably influenced by the mathematicization of language, it also clarifies the gendering of labor that attended both fields. To glean the irreducibly human message of Pnin, one must first learn to read like a computer — a word that, like "typewriter" before it, signals "the convergence of a profession, a machine, and a sex."12

Probability Machines

The difficulty of reading Pnin stems from the first-person omniscient perspective of its narrator. Pnin's narrator describes moments from which he is physically absent, exposing his unreliability through feigned omniscience. Pnin responds to the resulting discontinuities by calling the narrator a "dreadful inventor" (185). The narrator, in turn, suggests that Pnin is "reluctant" to "recognize his own past" (180). The difficulty for the reader, then, is that she receives information from a source that is both responsible for and challenged by the information itself. Indeed, Pnin's complaints about invented information constitute part of the novel's content, that which has itself been invented. Thus, the reader can only identify evidence of events as they happened (Pnin's "own past") through the orchestration of events as they are told (by a "dreadful inventor"). The problem facing the reader appears as nothing less than the distance between story and narrative itself — what the Russian Formalists termed fabula and sjužet. Readers resemble young feverish Pnin, then, straining to read his wallpaper design, emotionally moved by its aesthetic construction, yet convinced that its true meaning has been deliberately hidden. In fact, Pnin's cry of "dreadful inventor" recalls the narrator's description of himself as an "evil designer," an assignation the narrator uses to describe his concealment of a cryptographic message ascertainable only through a "key" to the wallpaper's "pattern." Nabokov's separation of story and narrative, when understood in the terms offered by narrative theory, formalizes the wallpaper's image of cryptographic reading, rendering its mathematical patterns in literary form.

In the very first chapter of the novel, Nabokov extends the cryptographic terms established by the wallpaper to a formal problem between story and narrative by staging a pointedly statistical contest between Pnin and the narrator. At first, it seems a coincidence of bad luck that Pnin takes the wrong train on his way to deliver a lecture to the Cremona Women's Club. Coincidence seems again to govern Pnin's world when he forgets his suitcase while transferring to a bus — and yet again, when on the bus, he realizes he has swapped the lecture in his pocket with a student essay. As these "diabolical pitfalls" of "unpredictable America" accrue, what at first looked like the mere reportage of chance events instead comes to resemble a pattern, as if Pnin's misfortunes have been designed (13). We see this when, faced with the quandary of where to secure his lecture so as not to confuse it with other papers, Pnin "theoretically" calculates "the chances" of success according to every available "possibility" (16). Here, Pnin engages in a game of probability. Eliminating first one contingency and then another, he strives to single out the decision that will most likely lead to his success.

After narrowing his choices, he determines that if the lecture remained in his current pocket, "it was physically possible" to accidentally "dislodge" it while pulling out his wallet, which we are told contains "a letter he had written, with my help" (16). The interjection of a first-person pronoun here confirms for the reader the narrative presence of a "dreadful inventor." We understand that the ostensible coincidences of Pnin's bad luck instead constitute nonaccidental circumstances deliberately organized to turn Pnin's misfortunes into a comedy of errors. The narrator admits as much when, as the seizure begins to take hold of Pnin, the narrator reveals that "now . . . Pnin felt what he had felt already on August 10, 1942, and February 15 (his birthday), 1937, and May 18, 1929, and July 4, 1920 — that the repulsive automaton he lodged had developed a consciousness of its own and not only was grossly alive but was causing him pain and panic" (21). The familiarity of his pain, the fact that it comprises a lifelong pattern, a sequence of precise dates, allows Pnin to catch on to its mechanics, though not without first construing his body as a "repulsive automaton." There is no difference here between the body in pain, an image of human excess, and the body as machine, an image of Pnin's ability to calculate probability. Which is to say, it is in this form that Pnin combines all of his papers, "stuffed" into his pocket, "thus thwarting mischance by mathematical necessity" (26). Unlike the situation with his wallpaper, here Pnin reads the chain of events successfully. He accurately translates the dreadful inventor's "mathematical" pattern into a meaningful message. When he stands before the Cremona Women's Club at the end of the chapter, lecture in hand, Pnin seems a more successful calculator of odds than the narrator — and the reader — who had bet on his failure. Thus, it is with this opening scene in mind that the narrator proclaims, "if the evil designer — the destroyer of minds, the friend of fever — had concealed the key of the pattern with such monstrous care, that key must be as precious as life itself" (23). The "key of the pattern" mentioned by the narrator here, or Pnin's own attempt elsewhere to read Pushkin's poetry as a "cryptogram" (68), indicate the debt Pnin's version of reading owes to cryptography.

At the time of Nabokov's writing, William F. Friedman served as chief cryptologist for the newly formed National Security Agency. Before the war, Friedman ushered cryptography into a new era through applications of mathematical pattern recognition to military communications, and his methods led to the successful decipherment of the Japanese cipher during World War II. Friedman had presented his most significant contribution in a government publication titled The Index of Coincidence and Its Applications in Cryptography (1935), which historian Ronald Clark has called "the foundation stone of the new cryptography."13 In this work, Friedman demonstrates how to align multiple strands of information presumably containing enciphered messages and mathematically distinguishes between patterns that are merely coincidences — "brought about by chance superimposition" — and those that are "causally related" recurrences, which is to say, "the resultants of the encipherments of plain-text letters."14 Friedman's theories revolutionized older methods that required expertise in multiple languages and a tremendous amount of guesswork. Using Friedman's methods, a single analyst working during World War II could crack a code mathematically, even without knowledge of the encrypted language. Friedman showed that languages adhere to certain laws of probability, a fact that reveals itself, in any language, through statistically significant repetitions. The trick entails isolating such repetitions from the insignificant coincidences that inevitably result, like the irregular repetitions on Pnin's wallpaper, recurring "here and there" in a random and "meaningless tangle."

The Index of Coincidence And Its Application in Cryptanalysis (1935) by William F. Friedman

These same cryptographic terms of pattern and coincidence proved instrumental in the 1950s in developing a theory of reading central to efforts in machine translation. Indeed, when Warren Weaver, the wartime director of the Rockefeller Foundation, wrote a memorandum that effectively launched machine translation in 1949, he wrote that he first conceived of the possibility of automatic translation when a "distinguished mathematician" developed a method of cryptography during the war that worked regardless of the language being decoded.15 "[O]ne naturally wonders," Weaver wrote, "if the problem of translation could conceivably be treated as a problem in cryptography." To illustrate, he continued, "When I look at an article in Russian I say: this is really written in English, but it has been coded in some strange symbols. I will now proceed to decode." Weaver called this conflation of different practices his "cryptographic-translation idea."16 The mathematics of cryptography led Weaver to identify in language the possibility of a "code," a series of "strange symbols" that reduces different languages to the same essential foundations. Weaver saw the patterns calculated by cryptography as "invariant properties" that must be "independent of the language used."17 Once machine translators developed the underlying mathematic logic of linguistic content, Weaver reasoned, the process could be automated. Translation would be the work of digital machines. Weaver's articulation of cryptographic patterns clearly reflects the influence of Freidman. Indeed, Weaver even enlisted Friedman as the government consultant for the Georgetown group that gave machine translation its first headlines.18

Nabokov's writing of Pnin, then, overlapped with what was understood to be the "golden age" of machine translation, as cryptographers and translators collaborated to conceptualize language as an object of statistical analysis.19 During this period, Nabokov also made substantial contributions to the study of translation.20 In the essay "Problems of Translation," Nabokov argued for the "impossibility" of literary translation, due to the inimitable power of Pushkin's metered prose, which instead necessitates a mode of "literal" translation. With "absolute exactitude," Nabokov claimed, literal translation adheres to "the essential pattern of the text," that which can be "scientifically studied"; the translator preserves semantic meaning and simple meter without attempting to replicate the intricate and "untranslatable" nuances of "literary" language, such as "beautifully onomatopoeic alliterations."21 Once again, the difference repeats the theme of pattern and coincidence found throughout midcentury theories of language. Like Pnin's wallpaper, Nabokov's essay identifies the "untranslatable" complexity of aesthetics and the "patterns" capable of being "scientifically studied" as the two forces that determine literary language.

Only a few months after Nabokov's publications on translation, Weaver penned a brief foreword to a collection of the seminal publications in the field of machine translation. Titled "The New Tower," the foreword begins: "We are told, by those who are sensitive to all the beauties of the Russian language, that it is completely futile to try to translate the poetry of Pushkin into any other language — futile not for a computer, but futile for the most able bilingual poet."22 All but naming outright the decade's most able bilingual Russian poet and translator of Pushkin, Weaver aptly summarized Nabokov's position on the futility of literary translation. Eschewing expectations of "elegance" and "style," Weaver asserted his own objective of "literal" translation, adding, "Pushkin need not shudder."23 Like Nabokov, Weaver claimed to remove aesthetics from the primary goal of translation, and he clarified instead that machine translation will enable the practical exchange of information. At the same time, Weaver's foreword clarified that Russian literature and its ostensible untranslatability had somehow entered the language of postwar machine translation.

Well Wrought Urns and Punched Cards

Had it not emanated from a "dreadful automaton," Pnin's thematization of the wallpaper's difficult yet beautiful aesthetics could be said to reinforce the reigning logic of literary criticism at the time. Not only did New Critics celebrate the irreducibly human category of language by constructing the notion of literary difficulty, they often did so in opposition to modern science. Cleanth Brooks's The Well Wrought Urn (1947), for example, distinguishes the "paradox" of poetic language from the "naïveté" of "science" writ large, and specifically from Basic English, a system of universal signification that, according to Brooks, "treat[s] language like notation."24 When Brooks wrote The Well Wrought Urn, Weaver had already recognized the contributions of Basic English to his own "cryptographic-translation idea."25 Literary difficulty, then, opposed not only a vague notion of science, but the specific development of mathematical theories of language and their machines. Confronted by such a machine — an "enormous" IBM newly stationed at Vanderbilt University — Donald Davidson observed that "with inhuman noise and precision, the machine was sorting the cards."26 The reduction of language to "notation" threatened the essence of humanist values for Brooks. For Davidson, mechanical language was out-and-out "inhuman." And as the arrival of such machines on university campuses allowed for the various early instances of the computational humanities, what we now call the "digital humanities," the New Critics established their celebration of linguistic difficulty in opposition to them: in this telling, close and distant reading were separated from the beginning.27

This association of New Criticism with anti-scientism, however, has obscured the ways in which the new cryptography influenced New Critical formalism, just as it had machine translation.28 In fact, W. K. Wimsatt conferred with none other than William F. Friedman while researching for his article, "What Poe Knew About Cryptography" (1943). Remarkably, this meant that Wimsatt developed his theories of literature while gaining insight into cryptography from the author of The Index of Coincidence. Declassified archival documents reveal that Wimsatt and Friedman exchanged letters on the application of cryptography to literature from late in 1941 to the summer of 1943.29 Though Friedman focused primarily on military forms of cryptographic communication, he considered cryptography's literary applications as well, publishing on literary subjects twice during his career: a 1936 article in American Literature that analyzed cryptography in Poe's "The Gold Bug" and a 1957 study with his colleague and spouse, Elizabeth Friedman, on Shakespearean cyphers.30 Defending the very authenticity and reputation of Shakespeare, the Friedmans debunked longstanding rumors that the bard's works contain cryptograms that hide an alternative authorial identity. Friedman later lent his expertise to Wimsatt for his own article on Poe and cryptography. Following Friedman, Wimsatt argued that cryptography helped Poe design interpretive puzzles that his readers must solve, that cyphers are merely one type of Poe's literary "devices." Despite what Wimsatt saw as Poe's literary virtues, however, he found in Poe no great cryptographer, technically speaking. Using the information gleaned from his correspondence with Friedman, Wimsatt went so far as to identify mathematic errors in Poe's probability statements about language.31 Having learned from the best in the field, Wimsatt portrayed himself as knowing more about the frequency patterns of language than Poe.

Elizabeth Friedman with an unnamed cryptographer (Courtesy of the George C. Marshall Foundation)

The influence of Friedman on Wimsatt's literary criticism is evident in "The Intentional Fallacy," which he famously coauthored with M. C. Beardsley in 1949.32 In The Index of Coincidence, Friedman showed mathematically that the meaning of a message depends on the decoder's ability to distinguish coincidences "brought about by chance" from "causally related" statistical patterns. His argument applied to hidden messages in Shakespeare as much as it did to intercepted military transmissions. "The mathematical theory of probability," Friedman wrote, allows Shakespearean patterns to be "calculated exactly," rather than showing up "by accident."33 In "The Intentional Fallacy," Wimsatt and Beardsley likewise argued that the literary work is not pulled "out of a hat," that it bears a "design" and a "plan," indeed, that it "does not come into existence by accident."34 The well-worn argument in "The Intentional Fallacy," that biographical interpretations are diminished by their dependency on authorial intention, links the hunt for intention to random chance; the critic approaches literature "in the spirit of a man who would settle a bet."35 Here, the authors describe literary criticism as the work of "a man" — which hardly seems surprising — but also a man protected from the vagaries of chance. The "fallacy" in question, moreover, doesn't describe intentionality tout court, but intentionality after the fact. In their own example, Wimsatt and Beardsley questioned whether a line from T. S. Eliot has been influenced by John Donne. While simply asking Eliot might provide empirical evidence of a sort, such a search for intentionality after the fact ultimately relies on the accidents of circumstance: that Eliot's answer today would be different from his answer tomorrow, that he would even remember the influence, that he might have "meant nothing at all." Against these chances, the authors felt safe to "weigh the probabilities" that a better method relies on the consistencies provided by close readings of the actual texts. "The Intentional Fallacy" suggests comparing Donne's language to Eliot's in order to identify any shared linguistic patterns, a mode of close reading that calculates the likelihood of their correspondence. Failing to find such consistencies, Wimsatt and Beardsley determined that the resemblance between Eliot and Donne is a coincidence rather than a causal relation. Maintaining their rejection of chance, they affirmed that "[c]ritical inquiries are not settled by consulting the oracle."36

Wimsatt and Beardsley contended that the work of art "works," that is, like a "machine" — one "demands that it work." They claimed that a poem's components must function together economically, free of irrelevancies like "'bugs' from machinery."37 I want to suggest that their analogy is symptomatic of, rather than merely incidental to the cryptographic distinction between chance and pattern woven throughout "The Intentional Fallacy." Referring to the programming errors or jams of digital tabulators, Wimsatt and Beardsley compared the work of the critic to debugging a machine. The analogy suggests that when Brooks contrasted poetry to "notation," or when Davidson called IBMs "inhuman," they complained about technical objects because they too closely replicated the methods of pattern recognition carefully honed by literary critics. After all, "the world wants a machine," Pnin's colleagues insist, not an English professor. The conflation of close reading and pattern recognition in "The Intentional Fallacy" thus resonates with scenes of machinic interpretation in Pnin. When Pnin instructs his students to view Pushkin's poetry as a "cryptogram," or when he attempts to read the patterns on his wallpaper like an "automaton" engaged in probabilities, such moments codify a kind of digital hermeneutics, an act of reading cryptographically.

This explains why Robert Penn Warren would assert, as he did in 1958, that "the New Criticism" resembles a "gigantic IBM machine — i.e., the 'method' — into which deft fingers of filing clerks feed poems and plays and novels and stories, like punched cards."38Warren imagined a "fallible human machine," a close reader working in concert with punch card technology; the "intelligence, tact, discipline, honesty, and sensitivity" of the one determines which informational patterns will be fed by "deft fingers" into the "systematic" workings of the other. Nabokov's novel advances a similar idea: Pnin holds onto his humanity, against the technological process translation had become, precisely because of what Warren claims as the exclusive provenance of humans, fallibility. At the same time, however, New Critics showed that human usage of language, however flawed, depends on technical mechanics, and that the two are virtually inextricable. There can be no doubt, at least in Warren's metaphor, that literary criticism, no matter how mathematically precise its methods, depends on a human. "Someone has to punch the cards," Warren wrote. In the discourse of postwar communications, though, this equates the work of the literary critic with that of a "card-puncher," one whose sensitivity to patterns transforms the labor of reading into information fed into a "gigantic IBM machine." Close and distant reading, not so separate after all.

Jamming the Machine

In the first chapter of Pnin, Nabokov establishes the terms of coincidence and pattern as a theme, which he elaborates with his description of the wallpaper. He then transmutes them into a formal concern, one that structures the events of Pnin journeying to his lecture at the women's club. Pnin's contest with the narrator, his "thwarting mischance by mathematical necessity," takes advantage, then, of what machine translators imagined as the terms of linguistic probability. Only now, the oscillation between pattern and coincidence describes the probabilities not merely of language, but of the literary event. In particular, the novel's formalization of probability derives from a gap between events as they happened and events as they are told. The Cremona lecture exhibits the effects of a transition from one to the other. In the story world of the novel, narration — the transition from fabula to sjužet — functions as a species of translation — the transition from a source language to a target language — which itself functions, according to midcentury theories of language, like cryptography — the transition from an encrypted cypher to a plain text message. Pnin's wallpaper, then, is more than a beautiful, though impossible, mathematical formula; it also offers an image of these variables, story and narrative, probability and improbability, as Nabokov imagines them conditioning the limits and possibilities of the novel's form.

The narrator draws attention to narrative limitation in his assertion, stated just as Pnin stands to deliver his unlikely lecture, that "doom should not jam" (25). He laments the short-circuiting of his careful building towards "doom," what he imagined as Pnin's failure, adding, "[t]he avalanche stopping in its tracks a few feet above the cowering village behaves not only unnaturally but unethically" (25-6). Improbability defies the laws that govern nature, like an "avalanche stopping in its tracks." But the narrator's complaint of an "ethical" infraction implies an agent of causality beyond pure chance. We are meant to understand, that is, that Nabokov himself has intervened, allowing Pnin to "thwart mischance by mathematical necessity," just as the narrator has deliberately shaped the events composing Pnin's story. If we understand such interventions to provide unlikely and external solutions to matters of literary plot, then they function as instances of a modern deus ex machina. When the narrator says "doom should not jam," his use of the word "jam" indicates the ironic condition of deus ex machina — an ancient literary device — in an aesthetic era increasingly identified by its tendency towards self-reflexivity. Pnin certainly exists on the horizon of what Mark McGurl calls "autopoetics" or, more extensively, what Mark Seltzer has elaborated as "the official world."39 Both McGurl and Seltzer draw from the language of systems theory to describe reality's staging of its own conditions as exemplified by literary works. Systems theory takes the feedback loops of cybernetics to demonstrate how cultural forms emerging in what Seltzer calls the "systems epoch" engage in perpetual self-reference, the incorporation of an outside observer into a closed system. McGurl and Seltzer have each clarified how systems theory offers an apt model for describing literary texts in which the closed story world stages its own conditions of production, often through the inclusion of authorial presence.

Pnin, however, doubles its inclusion of an observer, first through the narrator's observation of Pnin and also through Nabokov's observation of the narrator — a true feedback loop. The irony of this device is captured by the narrator's sense of surprise, not once but twice, when he fails to anticipate the possibility of external manipulation, even as he manipulates, from the outside, the story of Pnin. The second instance occurs in the novel's final pages, when Nabokov rescues Pnin from a painful encounter with the narrator, this time displacing him from the novel altogether, an event the narrator calls a "miracle" (191). The repetition of the doubled intervention — Nabokov's scheming against the already scheming narrator — clarifies that the "miracle" and the "jam" are one and the same, that the god in the machine has become a programming error. That is, the analog and therefore uncomputable mystery of the classical deus ex machina now enters into a quantifiable calculus of probabilities. As Seltzer reminds us, "reflexivity today is cheap."40 Which is to say, the self-referential tendency in contemporary fiction is commonplace — hence Seltzer's argument that we identify the moment as "a systems epoch." But even if the gods have always required a machine to mediate their entrance into creation, Pnin's innovation is to double the phenomenon, confirming that now these machines are digital.

Fiction writers in the age of digital machines, therefore, are like the "information technicians" for whom, according to Friedrich Kittler, "jam" serves as "the keyword" for "modernity itself"; or, as Gilles Deleuze writes, in his famous articulation of the modern control society: "jamming" is the "passive danger" of a society dependent on computers.41 The intentionally cybernetic language of Kittler and Deleuze designates modernity's order of technological control as precariously exposed to the inevitable malfunctions through which control diminishes. If postwar machines convey the modern impulse for control, then so do postwar novels. However, in the language of "The Intentional Fallacy," a "bug" in the poetic "machine" always refers back to a fallible inventor whose intentions remain present in the literary work, like original sin. The "bug" gives evidence of human error, and machines jam, not because of their imperfections, but because they run too perfectly. That is to say, unable to compute anything but perfect mathematics, a machine cannot extricate itself from a situation compromised by Warren's "fallible . . . card-puncher." Under the aegis of human error, the machine simply stops. The error, then, holds a strange and unintentional power — a "passive danger," as Deleuze writes — in the digital world.

What I have been suggesting is that, through his own errors, Pnin wields this power. However, Pnin's mistakes in translation do not reiterate a narrative in which man triumphs over machine. Instead, they expose the dependencies each has for the other. After all, the same idiosyncrasies and habits that signal Pnin's humanity to the reader render him undesirable in the modern university language program. He is fired and replaced to consolidate a department administration who had come to "believe only in speech records and other mechanical devices" (143). When Pnin's colleagues announce that "[t]he world wants a machine, not a Timofey," the punch line — "not a Timofey" — gains its comedic purchase from the gap between Pnin's too human "personality" and the machine "the world wants," a gap remedied by the joke's flattening of its subject into merely "a" Timofey. The joke, that is, doubles as an act of narration and translation, as it reduces the person of Pnin to a mere version of himself.

The department's reference to a translation machine that might replace the language professor defines not simply a temporal or historical marker of the novel's relationship to a particular technological project, that is, machine translation; the comment more significantly encapsulates the larger questions of language, labor, and technology during the Cold War that my reading recovers.42 These questions are echoed in the novel's vacillation between mechanical language, on one hand, and literary difficulty, on the other, as is apparent in a single, though lengthy, sentence that describes the intellectual culture of Pnin's language department. And here, we return to the question of gender evoked by the "girl operator" of the Georgetown event with which this paper began:

As a teacher, Pnin was far from being able to compete with those stupendous Russian ladies, scattered all over academic America, who, without having had any formal training at all, manage somehow, by dint of intuition, loquacity, and a kind of maternal bounce, to infuse a magic knowledge of their difficult and beautiful tongue into a group of innocent-eyed students in an atmosphere of Mother Volga songs, red caviar, and tea; nor did Pnin, as a teacher, ever presume to approach the lofty halls of modern scientific linguistics, that ascetic fraternity of phonemes, that temple wherein earnest young people are taught not the language itself, but the method of teaching others to teach that method; which method, like a waterfall splashing from rock to rock, ceases to be a medium of rational navigation but perhaps in some fabulous future may become instrumental in evolving esoteric dialects — Basic Basque and so forth — spoken only by certain elaborate machines (10).

"As a teacher," Pnin is far from the "difficult" and "beautiful" of modernist aesthetics. Nabokov derides the difficult and beautiful as language "infused" with "magic knowledge," and laments that the mere effect of this academic skill amounts to silly affectations of culture — "tea," "caviar," and "songs." He opposes the diminished version of the poetic power of language to an "ascetic" utility of "modern scientific linguistics." Repeating the phrase with which the sentence begins, the narrator explains that "as a teacher," Pnin feels cut off from the "lofty halls" of linguistics, which exchanges "language itself" for a "fraternity of phonemes," or a mathematical system of linguistic parts. The scientific view of language boasts of a "method" that, the narrator imagines, construes languages like "Basic Basque" as "spoken only by certain elaborate machines." Here the narrator contrasts the language of machines with aesthetic expression, affirming a fundamental dichotomy in the era of "two cultures."43 The gendered dimension of translation to which I have thus far only gestured is elucidated here: the "maternal bounce" and "Mother Volga songs" of aestheticism expresses a femininity that contrasts the cold, mechanical masculinity of linguistic "fraternity." The sentence reenacts the journey to the Cremona Women's Club, wherein Pnin encountered the "diabolical pitfalls" that lie between the space of the campus and the site of female intellectual labor at its periphery.

Avon Books' first edition of Pnin (1957) highlights the importance of gender in shaping its protagonist's social world

The general effect of this lengthy sentence works to oppose the curt language of machines with aesthetic expression, certainly. More significantly, though, the sentence conjoins them, in so much as Pnin cannot remain "far from" one domain without also "approaching" the other. That is, their instrumentalization of language, whether aesthetically or scientifically, confronts him in his university work, as indicated by the repetition of the phrase "as a teacher." In the end, Pnin cannot divorce language from the attributes of difficulty or beauty, any more than he can those of the modern and scientific, for it is not an escape from either but their particular reconciliation that Pnin models. The sentence thus unites the masculine "scientific" and "modern" with the feminine "difficult and beautiful" — those two forces that permeate Pnin's attempt to read his wallpaper — by construing them as inextricably tethered together in the character of Pnin. The New Critical turn to cryptography thus appears as an effort to enforce a sense of literary criticism performed, as Wimsatt claimed, "in the spirit of a man," rather than with the "maternal bounce" of Pnin's "stupendous ladies," a distinction produced by the mechanical "fraternity" of digital machines. However, the irony of Warren's comment, that the postwar literary critic amounts to a kind of "card-puncher," is that at the time, most card punchers were women. The deliberately gendered divisions of Pnin's department, then, also serve to remind us that the advent of digital machines necessitated a largely unseen contingent of female labor that achieved the work of cohesion in which Pnin also engages. This is certainly true of the Georgetown demonstration, which the New York Times described as the combination of a "mechanical part of the translation system," the machine itself, and "a literary part of the system," the linguistic model of language, which clearly corresponds with those two factions of Pnin's department. But as we have seen, the Times also establishes that the two parts were conjoined or brought together by "a girl operator" — a transparently dismissive description — who punched the cards and fed them to the machine, thus introducing the "literary" to the "mechanical."44 The female operator makes the work of translation possible, despite the fact that, because "the operator did not know Russian," the words she types are, as the Times is keen to emphasize, "meaningless (to her)."45

Pnin may occupy the queer middle ground between "maternal" aestheticism and "fraternal" linguistics. He is, in the narrator's phrasing, "almost feminine." But in the paradox that pervades all contemporary systems of labor, Pnin also contributes, simultaneously, to those very dynamics of imbalance. His own method of translation places him at either end — the "mechanical" and the "literary" — of a system that features, in its middle, a denigrated female employee on whom Pnin's acts of translation depend. To produce his lecture, the very document that becomes, on the way to a women's club, the source of a game of chance, Pnin "laboriously translate[s] his own Russian verbal flow, teeming with idiomatic proverbs, into patchy English," at which point the work of revision falls onto a typist, "Dr. Hagen's secretary," who delivers to Pnin a typescript with which he "delete[s] the passages he [cannot] understand" (15). As Pnin translates once (for mechanics) and again (for meaning), the production of the lecture hinges on the secretary in between. Indeed, in Pnin, translation is never the work of an actual machine, any more then it is a facile renunciation of mathematical theories of language. Rather, Nabokov presents translation as a problem of reconciling the human body, and not just male bodies, with technical processes, as expressed, for example, in the physiognomy of Pnin's mouth — "the larynx, the velum, the lips, the tongue" — which functions, in this fictional world, according to the basic mechanics of a machine, from the "motion" of its parts to its "production" of sound (66). At the birth pangs of the digital age, Pnin neither acquiesces to the hollow acceptance of statistics as the era's reigning epistemology, nor retreats, predictably, to modernist aesthetic autonomy. Instead, the novel reconciles science and art, exposing them as never having been separate.

Sean DiLeonardi is a Ph.D. candidate and Dean's Fellow at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He is currently completing a dissertation entitled Likely Stories: The American Novel in the Age of Digital Probability.

References

The author would like to thank Eric Downing, Stanislav Shvabrin, the participants of the 20/21 Century Workshop at the University of Chicago and the anonymous Post45 reviewers for their generous feedback, with special thanks to Florence Dore, whose keen readings improved this article at every stage of its development.

- Robert K. Plumb, "Russian Is Turned into English by a Fast Electronic Computer," The New York Times, January 8, 1954, 1.[⤒]

- Ibid.; Robert K. Plumb, "Data for Electronic Computing Machines Are Prepared by Experts for Difficult Tasks," The New York Times, August 8, 1954, E9.[⤒]

- Vladimir Nabokov, Pnin (New York: Vintage, 1957), 15. Subsequent references in parentheses. [⤒]

- Gennady Barabtarlo views Pnin's wallpaper not only as an image of the novel itself, but calls its recurrence of patterns "the single most important and original feature" of "every Nabokov book." See Barabtarlo, Phantom of Fact: A Guide to Nabokov's Pnin (Fareham: Ardis, 1989), 79.[⤒]

- Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita (New York: Vintage International, 1955), 315.[⤒]

- William F. Friedman, The Index of Coincidence and its Applications in Cryptanalysis (Washington: The United States Government Printing Office, 1935), 1.[⤒]

- Mark Seltzer has argued that this tendency describes the workings of an "official world," the incessant staging of the conditions of reality paradigmatically realized in literary works.[1] Because the official world is endemic to midcentury literary culture, as Seltzer shows, I explain how the labor divisions of the postwar university give rise to a particular version of self-reflexivity that I call cryptographic reading. See Mark Seltzer, The Official World (Durham: Duke Press, 2016); Mark Seltzer, "The Daily Planet," Post45: Peer-Reviewed (Dec. 2012).[⤒]

- For example, scholars describe "the cryptographic character" of Nabokov's prose, "decode" his literary "ciphers," and identify Pnin's "intricate play of patterns." See, respectively, William Rowe, "The Honesty of Nabokovian Deception" in A Book of Things about Vladimir Nabokov, ed. C. Poffer (Ann Arbor: Michigan University Press, 1974), 185; John V. Hagopian, "Decoding 'Signs and Symbols'" in Anatomy of a Short Story: Nabokov's Puzzles, Codes, and "Signs and Symbols," ed. Y. Leving (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 298; Julian W. Connolly, "Introduction: Nabokov at 100" in Nabokov and his Fiction: New Perspectives, ed. J. Connolly (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 3. For other readings of Pnin derived from the identification of patterns, see Paul Grams, "Pnin: The Biographer as Meddler" in A Book of Things about Vladimir Nabokov," 192-201; David Richter, "Pnin and 'Signs and Symbols': Narrative Entrapment" in Anatomy of a Short Story, 224-35; William Carroll, "Pnin and 'Signs and Symbols': Narrative Strategies" in Anatomy of a Short Story, 236-50; Robert Alter, "Nabokov for Those Who Hate Him: The Curious Case of Pnin" in Nabokov Upside Down, ed. B. Boyd and M. Bozovic (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2017), 197-209.[⤒]

- On the "difficulty" of modernism, which the New Criticism made central to its development of a midcentury critical apparatus, see John Guillory, Cultural Capital: The Problem of Literary Canon Formation (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1993). Mark McGurl has shown that campus novels of the period tend to embroil the formal aspirations of literary craft with the technological objects of scientific application. McGurl calls this amalgamation "technomodernism." Because Nabokov "didn't quite get with the program," that is, because Nabokov foregrounds a "mystical submission to aesthetic authority," McGurl begins his analysis of technomodernism with John Barth's 1966 novel Giles Goat-Boy, not Pnin. One aim of this article is to show that the undocumented history of machine translation in Pnin, published nearly a decade before Barth's mock epic novel, unseats longstanding presumptions about Nabokov's modernism that have obscured the novel's later reception. McGurl, The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), 5.[⤒]

- Fredric Jameson, for example, insists that Nabokov's "late modernism" continues to reject "the experience of the machine." See Jameson, Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke UP, 1991), 305. Jameson means to uphold modernists' "hostility to" technology, and to contrast that position with a contemporary "affirmation, when not an outright celebration of the market as such." But, as we shall see, Nabokov incorporates machine translation and its language technologies into the high modernist aesthetics of Pnin, suggesting that he belongs with "technomodernists" after all. Indeed, Duncan White argues that Nabokov negotiated "a problematic relationship of late modernist ideas of authenticity and autonomy with the pressures of the literary marketplace," and Stephen H. Blackwell has shown that scientific discourse influenced Nabokov's art. My reading of Pnin bears this out in relation to machine translation. See White, Nabokov and his Books: Between Late Modernism and the Literary Marketplace (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 8 and Blackwell, The Quill and the Scalpel: Nabokov's Art and the Worlds of Science (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2009). Several studies lay the groundwork for this complex understanding of modernism in relation to machines. See Hugh Kenner, The Mechanic Muse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987); Mark Goble, Beautiful Circuits: Modernism and the Mediated Life (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010); Tim Armstrong, Modernism, Technology and the Body (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998). [⤒]

- As such, this article builds on recent work by Michael Gavin that argues for a conceptual link between computational linguistics and midcentury literary criticism. Gavin describes William Empson's theory of linguistic ambiguity as prefiguring later advances in vector semantics, thus highlighting the "automaticity" of close reading (643). The modeling of vector semantics becomes possible, as Gavin notes, only in subsequent iterations of machine translation, after technical advancements and the expansion of data corpora that address the multivalent complexities of language. My research instead concentrates on the initial moments wherein machine translators sought to reduce such complexities to a cryptographic code, a one-to-one ratio between two languages that nevertheless corresponds to New Critical forms of pattern recognition. In both cases, the statistical realization of language, long associated strictly with scientific endeavors, proves vital to the development of literary practice. See Gavin, "Vector Semantics, William Empson, and the Study of Ambiguity," Critical Inquiry 44 (Summer 2018): 641-673.[⤒]

- Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young and Michael Wutz (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986), 183.[⤒]

- Ronald Clark, The Man Who Broke Purple (Boston: Littlehampton Book Services, 1977), 77.[⤒]

- Friedman, The Index of Coincidence, 11.[⤒]

- Warren Weaver, "Translation" in Machine Translation of Languages, ed. W. N. Locke and A. D. Booth (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1955), 15.[⤒]

- Ibid., 18.[⤒]

- Ibid., 16.[⤒]

- Highly skeptical of the new field, Friedman would later write, "I laughed from my first contact with MT to the very end." See Clark, The Man Who Broke Purple, 235. [⤒]

- Brian Lennon writes that "the Georgetown demonstration clearly marked a surge forward . . . It was the beginning of a golden age for MT, defined by major international conferences, a critical mass of important publications, and (in the United States) easy access to generous government, military, and private funding even before the Sputnik crisis of 1957." See Lennon, "Machine Translation: A Tale of Two Cultures" in A Companion to Translation Studies, ed. S. Bermann and C. Porter (New York: Wiley, 2014), 140. Central to these developments was Roman Jakobson. Not only was his theory of linguistic phonemes routinely cited in machine translation publications, but Jakobson himself began collaborating with Weaver, and by 1950, the Rockefeller Foundation awarded Jakobson a large grant to research the statistical logic of linguistic structures, necessitating several trips to Russia. See Bernard Dionysus Geoghegan, "From Information Theory to French Theory: Jakobson, Lévi-Strauss, and the Cybernetic Apparatus," Critical Inquiry 38.1 (2011): 96-126. Nabokov references these trips in a letter to Jakobson that effectively ended their professional collaborations and personal friendship. "Frankly," Nabokov wrote, "I cannot stomach your little trips to totalitarian countries, even if these trips are prompted merely by scientific considerations." Vladimir Nabokov: Selected Letters: 1940-1977, ed. Dmitri Nabokov and Matthew J. Bruccoli (San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1989), 216. The degree to which Nabokov's relationship with Jakobson shapes the derisive representation of linguistics in Pnin has never been considered, though Jakobson certainly offers a plausible link between machine translation and the references to linguistic machines in the novel.[⤒]

- See Vladimir Nabokov, "On Translating 'Eugene Onegin,'" The New Yorker, January 8, 1955, 34; "Problems of Translation: 'Onegin' in English," The Partisan Review, Fall 1955, 496-512.[⤒]

- Nabokov, "Problems of Translation," 512.[⤒]

- Warren Weaver, "The New Tower" in Machine Translation of Languages, ed. W. N. Locke and A. D. Booth (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1955), v.[⤒]

- Ibid., vii.[⤒]

- Cleanth Brooks, The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry (London: Harvest, 1949), 10. Brooks's comment refers specifically to Stuart Chase, who saw Basic English as evidence for the possibility of unimpeded scientific communication. See Stuart Chase, The Tyranny of Words, 6th ed. (London: Methuen, 1947).[⤒]

- Basic English was formulated by I. A. Richards and C. K. Ogden. In his 1949 memorandum, Warren Weaver noted, "This must be very closely related to what Ogden and Richards have already done for English" ("Translation" 23). Rita Raley has expanded on this historical connection, concluding, "To suggest a link between Basic English and a mechanized English is not to speak of a philosophical relation between language and technology but of a practical and cultural-historical relation" (302). See Raley, "Machine Translation and Global English," The Yale Journal of Criticism 16.2 (2003), 302.[⤒]

- Donald Davidson, "In Justice to so Fine a Country," The Sewanee Review 63 (Spring 1955): 144-5.[⤒]

- Many histories of the digital humanities point to its beginnings with Father Roberto Busa, whose Index Thomisticus comprised an early work compiled, in part, by IBM machines. See, for example, Meredith Hindley, "The Rise of the Machines," Humanities 34.4 (2013). Recently, Rachel Sagner Buurma and Laura Heffernan have argued that it was Josephine Miles, not Busa, who inaugurated distant reading with her index of Dryden, which used a similar tabulation machine several years prior to Busa. See "Search and Replace: Josephine Miles and the Origins of Distant Reading," Modernism/Modernity Print Plus 3.1 (2018). Finally, in "A Genealogy of Distant Reading," Ted Underwood has distinguished between the digital humanities and non-machine distant reading, a methodology derived from social science practices in the humanities that predates digital technologies. Underwood's argument helpfully gestures toward the epistemological, rather than just material constituents of literary methodologies, but this undoing of conventional history arguably works both ways. The New Critics, in my telling, implicate aspects of digital cryptography into their method of close reading without recourse to actual digital machines. Ted Underwood, "A Genealogy of Distant Reading," Digital Humanities Quarterly 11.2 (2017). [⤒]

- Arguing that the New Critics simultaneously borrowed from and condemned postwar sociological methodologies, Stephen Schryer provides an excellent summary of the New Critical tension between scientism and anti-scientism. Schryer, Fantasies of the New Class: Ideologies of Professionalism in Post-World War II American Fiction (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 49. [⤒]

- Correspondence between Friedman and Wimsatt occurred while Friedman was head of the U.S. Signals and Intelligence Service and was therefore classified until well after Friedman's retirement. See Letters to/from Professor Wimsatt, folder 367, William F. Friedman Collection of Official Papers, National Security Agency; and Letters from William Friedman, series IV, box 49, folder 98, Wimsatt (William Kurtz) Papers (MS 769), Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library.[⤒]

- See "Edgar Allan Poe, Cryptographer," American Literature 8.3 (1936): 266-280; William F. Friedman and Elizabeth S. Friedman, The Shakespearean Ciphers Examined (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957). [⤒]

- W. K. Wimsatt, "What Poe Knew About Cryptography," PMLA 58.3 (1943): 772.[⤒]

- W. K. Wimsatt and M. C. Beardsley, "The Intentional Fallacy," The Sewanee Review 54 (Summer 1946): 469-488.[⤒]

- Friedman, Shakespearean Ciphers, 21.[⤒]

- Wimsatt, "The Intentional Fallacy," 469.[⤒]

- Ibid., 487.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid., 469.[⤒]

- Robert Penn Warren, Selected Essays (New York: Random House, 1958), xii.[⤒]

- Only in this case, the reflexivity of Nabokov's fiction stages, not the entire campus space nor a total social system, but a particular model of cryptographic reading emerging in American universities. See McGurl, The Program Era; Seltzer, The Official World. [⤒]

- Mark Seltzer, "The Daily Planet."[⤒]

- Friedrich Kittler, "Signal-to-Noise Ratio" in The Truth of the Technological World, trans. Erik Butler (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013), 175; Gilles Deleuze, "Postscript on the Societies of Control," October 59 (Winter 1992), 6.[⤒]

- For Pnin's contribution to the postwar campus novel's association with McCarthyism see Eric Naiman, "Nabokov's McCarthyisms: Pnin in The Groves of Academe," Comparative Literature 68.1 (2016), 79.[⤒]

- In 1959, British scientist and novelist C. P. Snow famously described the "two cultures" that divided Western intellectual life into the sciences and the humanities. Snow first made his diagnosis in the 1959 Rede Lecture, published thereafter as The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1959).[⤒]

- Plumb, "Russian Is Turned Into English," 1. Wendy Hui Kyong Chun brilliantly articulates the organization of occluded female labor in midcentury computation when she describes a female programmer who mediates between a higher-ranking man and the actual machine. Chun, "On Software, or the Persistence of Visual Knowledge" Grey Room 18 (Winter 2004): 26-51. Relatedly, Marie Hicks argues that systematic gender discrimination leads to the demise of the large female contingent of computational labor, particularly in the UK context. Hicks, Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing (Boston: MIT Press, 2017).[⤒]

- Plumb, "Russian Is Turned Into English," 5.[⤒]