Stranger Things and Nostalgia Now

It has become commonplace to lament the loss of an American childhood in which unsupervised play and everyday encounters with moderate danger build independence, resilience, and creativity. Today's highly-regulated kids supposedly lack fortitude and miss out on the risky fun and adventure of yesteryear's childhoods.1 In a New York Times op-ed titled, "The 'Stranger Things' School of Parenting," Anna North argues that the series offers a corrective to the "hyper-parenting" of today. She writes, "'Stranger Things' is a reminder of a kind of unstructured childhood wandering that—because of all the cellphones, the fear of child molesters, a move toward more involved parenting or a combination of all three—seems less possible than it once was." North asks the reader to view Stranger Things as a model for a loosened approach to parenting that acknowledges the world may hold dangers, but accepts that "bravery needs its own space to grow."2

In the 1980s, American culture turned away from older childhood freedoms. Today, Stranger Things' image of unsupervised kids biking headlong into mystery and adventure can exist only as nostalgic evocation of past fictions. What happened in the 1980s to bring us to this point? A string of child abductions and murders in the late 70s and early 80s garnered a new level of media coverage. Perhaps most notoriously, the disappearance in 1979 of six-year-old Etan Patz, walking alone to his school bus in New York City, precipitated the widespread perception of a rise in kidnapping and child molestation. Hannah Rosin summarizes the cultural upshot of this infamous case: "the fear drove a new parenting absolute. Children were never to talk to strangers."3 And they weren't supposed to go anywhere alone.

Unsurprisingly, the figure of the missing or endangered child became an object of literary and cinematic fixation. Consider, as a tiny sample, Steven Spielberg's E.T: The Extraterrestrial (1982) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Stephen King's novel It, King's novella The Body and Rob Reiner's film adaptation, Stand By Me (1986), and Tobe Hooper's Poltergeist (1982). This is the source material for Stranger Things, which has, at its heart, the figure of the missing child. But the ultimately soothing work it does for us now is utterly different from what those movies and books did for us then.

Then, the genres of horror, science fiction, and family melodrama attempted to work through the crisis of bourgeois patriarchy and the "disintegration and transfiguration of the traditional American" nuclear family.4 The figure of the child was the locus of this work.5 According to Vivian Sobchack, these genres offered mostly regressive responses to familial upheaval: failed and monstrous horror film fathers; confused and weakened fathers of the family melodramas; fathers of science fiction film that attempt to regain their patriarchal strength by stepping outside the space of the nuclear family home and being reborn as children themselves.6

Stranger Things' pastiche of genre films from this period restages scenarios of family and patriarchy in crisis, but this narrative content no longer reflects the social tensions to which the show's generic work responds. Instead, Stranger Things' own generic convergence responds to today's perception of childhood as itself in crisis, which has its roots in the very period of Stranger Things' setting, what Hannah Rosin terms "the era of the ubiquitous missing child."7

Though discussions of the show don't reflect it, Stranger Things grants as much significance to its two flawed but well-intentioned parents—Joyce and Hopper—as to its child characters. The two serve to negotiate the contemporary crisis of childhood by way of its mass-cultural past. The interconnected resolutions of these characters' struggles enable an imaginary trans-temporal resolution to today's crisis of childhood, in which the independent kids we wish still existed and the involved, caring parents that exist now meet safely in a single time and space.

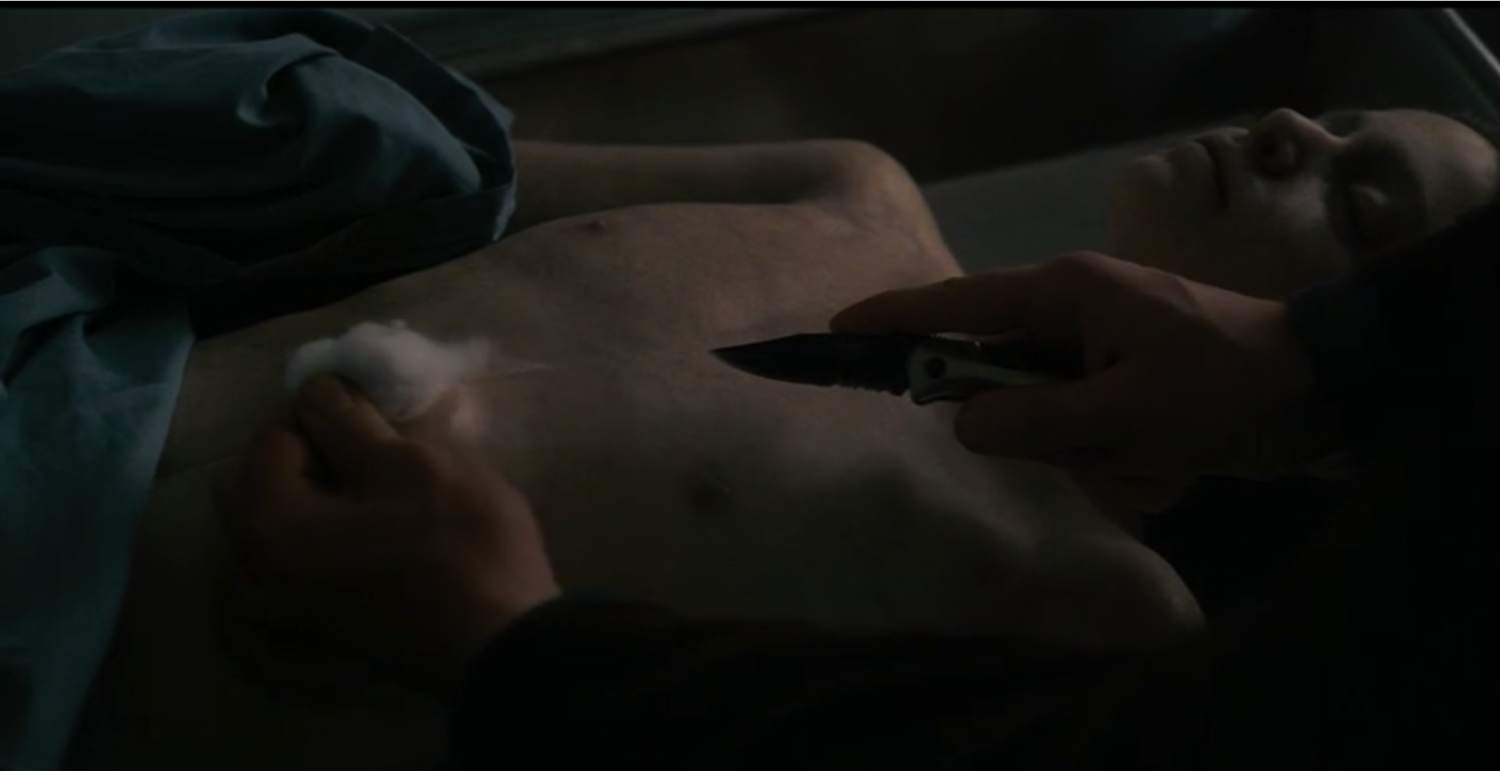

Like Stephen King's It, written and published at the height of the era of faces on milk cartons and National Missing Children's Day, Stranger Things uses a child's disappearance and apparent death as its plot's inciting incident. After Will disappears, his mother Joyce's insistence that he is somehow present in the house and that she can communicate with him through her system of letters and Christmas lights marks her as increasingly unstable and pitiable in the eyes of others. But by the show's logic, Joyce's devices allude to unconventional methods of communication in the show's forebears, such as the tones and colors used to converse with friendly aliens in Close Encounters or the family communicating with abducted daughter Carol Anne through the television in Poltergeist. Thus, the climax of Episode Three, "Holly, Jolly," in which Will's apparent corpse is pulled from the lake, evokes pathos, even as the viewer has reason to suspect—if the show keeps faith with its allusions—that Will is still alive.

The scene employs Griffith-esque crosscutting among the kids on their bikes, the police in their cars, and, finally, Joyce on foot, all rushing to the quarry. But the scene is a tearjerker because of its adherence to the temporal structure of melodrama, in which pathos is produced when an action is too late, when the tension between desire and reality is dissolved.8 The editing and music imply that Will might be found alive, but the dredging up of his body disappoints this expectation. The scene resolves with the crosscutting structure with which it began, leaving the viewer with the image of twin embraces between mothers and sons, foregrounding Joyce's apparent loss of her youngest.

But the next episode, "The Body," wastes no time resolving any uncertainty concerning Will's survival. "The Body" initiates a narrative resolution to the crisis of a child's disappearance through intersecting dramas of recognition and belief centered on a parent —Joyce. Through these narrative devices, the episode imbricates generic conventions of melodrama and horror. It reorients the viewer's and the characters' understanding of events, and cathartically shifts them from the passive suffering at the end of the preceding episode to active, investigative curiosity.

The central conflict — the pain of losing a child — registers the episode as a maternal melodrama. When Hopper visits Joyce at her home to discuss Will's apparent death, Joyce's desperate insistence that Will is still alive but in grave danger, and that she can speak to him through the Christmas lights, would, within the conventionally realistic space of melodrama, be taken as irrational expressions of unmanageable grief — Hopper's reaction. Melodrama produces emotional investment by granting the viewer knowledge of a character's innocence or virtue, qualities that go unrecognized by other characters. The viewer agonizes over the public misrecognition of the protagonist's true qualities, until cathartic moments when these qualities are justly recognized. In the scene at Joyce's house, the viewer understands Hopper's disbelief, while wishing for Joyce to be right and to have her rightness recognized — this is the drama of recognition.

Horror and suspense films with elements of what Todorov termed "the fantastic" stage their own dramas of recognition, predicated on characters' encounters with mysterious events followed by adjudication over rational or supernatural explanations.9 Often, the viewer's privileged knowledge of the supernatural explanation aligns her with the protagonist, building tension as she waits for the other characters to catch up. Validation of Joyce's belief in Will's survival and the supernatural explanation upon which this belief depends will in turn validate her emotional state (treated by Hopper with gentle condescension) and, further, her status as good mother according to the terms of maternal melodrama. She is putting everything of her own on the line — her job, home, and public perception of her competence as a parent to make the case that Will is still alive.

The narrative arc of the "The Body," then, functions to bring the other characters around to Joyce's belief, and this resolution of the melodramatic struggle for recognition enables the remainder of the season to shift into an action narrative. The season's plot follows a structure Noël Carroll identifies in many horror films, in which the characters first try to figure out whether the monster exists, and, once that is established, determine how to defeat it.10 In Stranger Things, it is not just the existence of a monster — here, the Demogorgon in the Upside Down—that is at stake, but a larger governmental-scientific conspiracy. The characters' newly shared alignment in belief in the supernatural dissolves the problem of recognition derived from melodrama: Joyce's son is still missing, but everyone that matters now believes that she is right and that she is a good mother.

The confirmation of the supernatural and the conspiracy to cover it up initiates an imaginary resolution to the real-world fears endemic to the period of the show's setting: the child gone missing. King's It, a major inspiration for the show, enacts these fears with its horrific inciting incident and subsequent assaults on children, all linked thematically to weak or monstrous fathers. By contrast, Stranger Things transposes to the 1980s a contemporary message of reassurance that subtends today's nostalgia for unsupervised childhood. After all, this argument goes, the rate of child stranger abductions didn't actually rise during this period; the fear was, and is, mostly in our heads.11 The revelation of the conspiracy to cover up Will's faked death thus functions at an emotional level in the way that the 1970s conspiracy thrillers analyzed by Fredric Jameson in The Geopolitical Aesthetic function at a cognitive level—to make the incomprehensible comprehensible, or at least bearable.12

It is much easier to believe in a supernatural shadow world prowled by a Demogorgon and guarded by a shady governmental-scientific conspiracy than it is to believe that your child lies dead in a morgue before your eyes. In the show's convergence of science fiction, horror, and family melodrama, the existence of the supernatural resolves the problem of maternal loss. But this pathos of loss conventional to melodrama here more specifically periodizes "helicopter parenting" itself; Stranger Things' pastiche of It and other missing child narratives of the 1980s simultaneously evokes the fears that take hold in this period and works to free the contemporary viewer of these fears.

In Stranger Things' 1980s sources, the problem to work through is the crisis in patriarchy, whereas independent childhood adventure is a mostly unproblematized given. The melodramatic drama of recognition that centers on Joyce in Stranger Things belongs, in Spielberg's movies, either to the father (in Close Encounters) or to the son (in E.T.). In both, the wondrous power of the alien resolves the problem of the missing or ineffectual father. In the climax of Close Encounters, Barry, the film's missing child, returns safely from the alien spacecraft. But, as Sobchack points out, rather than form a new family unit with Barry and his single mother Jillian, protagonist Roy Neary, estranged from his own family, literally and figuratively takes the place of the child—boarding the spaceship and turning his back on paternal responsibility altogether.13

Through Hopper, Stranger Things imagines a way forward for paternity that the earlier genre films are unable to envision—but the ideological function of this resolution is to alleviate contemporary anxieties about unsupervised childhood. Stranger Things initially presents an array of negative fathers and father figures straight out of 70s and 80s fictions: Will and Jonathan's father Lonnie, absent and abusive; Mike and Nancy's father, barely present even when in the room; Dr. Brenner, a monstrous emotional manipulator; and Hopper, isolated and self-destructive following his daughter's death from cancer. But these figures are throwbacks, as much elements of pastiche as the meticulous period clothing and interior décor. The loss of children's autonomy, not patriarchy in decline, is the problem to be grappled with; popular commentary like "The Stranger Things School of Parenting" rightly suggests that the show prods viewers to imagine an alternative to the seemingly intractable parental fears born in the 1980s.

During the action-oriented plot in the second half of the first season, everyone works toward rescuing Will. The season's final episode, "The Upside Down," resolves Hopper's paternal melodrama of grief over his daughter's loss. As Hopper uses CPR to revive Will from near death in the Upside Down, the show again employs melodramatic crosscutting to align Hopper's desperate but effective actions with his memory of passively witnessing his daughter's death in a hospital room while doctors fail to revive her.

This generic convergence, in which Hopper heroically saves the missing child in a scary, supernatural place in order to resolve the grief from a loss experienced in a realistic place conventional to melodrama, enables Hopper to emerge from the show's field of bad fathers to become the sort of good father that the films of the 70s and 80s could not quite envision: protective but nurturing, seeking to understand the child rather than control or become the child. But the primary function of this generic convergence and narrative resolution is to offer viewers the image of a reassuring safety net beneath the potential dangers of unsupervised childhood adventure. As this scene envisions it, independent childhood might be risky, but it will be okay in the end, mom and dad will be there, even if mom and dad are separate, romantically uninvolved individuals—even if this is a "Modern Family."

The season's end completes a pattern of reassurance begun with "The Body," an episode whose title is taken from the Stephen King novella that was adapted as Stand by Me, a novella whose story of childhood friendship and adventure was King's trial run for It. But King's bodies, in both books, are those of truly dead children. Stranger Things cuts open the body to find that it's a trick, and that the fear is just in our heads. Stranger Things' generic convergence and narrative resolutions propose a foundationally different relation to the historical events of the 80s that inaugurated the "era of the ubiquitous missing child" and led to today's crisis of childhood. They construct an alternate timeline enabled by the transposition of the nurturing and present parents of today back to the past to rescue the missing children from the moment at which these parents were called into being.

Jason Middleton is Associate Professor in the English Department and the Graduate Program in Visual and Cultural Studies, and director of the Film and Media Studies Program, at University of Rochester. He is author of Documentary's Awkward Turn: Cringe Comedy and Media Spectatorship (Routledge, 2014), and co-editor of Medium Cool: Music Videos from Soundies to Cellphones (Duke UP, 2007). His essays have been published in Cinema Journal, Feminist Media Histories, The Journal of Visual Culture, Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere.

References

- Hannah Rosin, "The Overprotected Kid." The Atlantic, April 2014; Christina Schwartz, "Leave Those Kids Alone." The Atlantic, April 2011; Michael Chabon, "The Wilderness of Childhood," in Manhood for Amateurs (New York: Harper, 2009).[⤒]

- Anna North, "The 'Stranger Things' School of Parenting." New York Times, August 5, 2016.[⤒]

- Rosin, "Overprotected Kid."[⤒]

- Vivian Sobchack, "Bringing it all Back Home: Family Economy and Generic Exchange," in American Horrors: Essays on the Modern American Horror Film, ed. Gregory A. Waller (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 176.[⤒]

- Ibid., 176.[⤒]

- Ibid., 185.[⤒]

- Rosin, "Overprotected Kid."[⤒]

- Linda Williams, "Melodrama Revised," in Refiguring American Film Genres, ed. Nick Browne (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998), 69.[⤒]

- See Noël Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror, or, Paradoxes of the Heart (New York and London: Routledge: 1990), esp. 144-157.[⤒]

- Ibid., especially Chapter Three, "Plotting Horror."[⤒]

- Rosin, "Overprotected Kid."[⤒]

- Fredric Jameson, The Geopolitical Aesthetic: Cinema and Space in the World System (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992).[⤒]

- Sobchack, "Bringing it all Back Home," 185.[⤒]