Issue 3: Stoppage Time: Timescales of the Present

The first illustration in Lydia Millet's novel Mermaids in Paradise (2015) depicts the back of a man's head as he gazes down at his laptop. What could be more representative of contemporary life, or more trivial? Our narrator, Deb, has mentioned that her fiancé Chip is a gamer, but does this detail really need photographic illustration? Especially when his laptop screen shows "one of his many avatars" flying a "steam-punk zeppelin, pulled by a team of elegant purple dragons."1

Isn't this illustration just a little too cute? Well, yes. Its subject — Chip, laptop, and dragons — falls somewhere between funny, cute, trivial, and annoying. But there is more to this photographic illustration than its subject: fingertips interposed between Chip and the page that surrounds him. The hand frames this image as an image — it is not an illustration seamlessly worked into the fictional world it depicts. Whose fingers are those? The perfect manicure hints that they may be Deb's, but the fingers also overlap with the reader's as she holds the book itself (or, for that matter, as she holds an e-reader). The effect is an uncanny layering of the fictional Chip's hand on his keyboard, the mysteriously interposed hand holding the image, and the reader's grasp on the material book. This photographic illustration teaches us a few things about contemporary novels that include photographs: first, the subject of the illustration may not be as important as its material presence on the page; second, it has material presence both within the fiction but also outside it, in our own world; and finally, its materiality is not necessarily in competition with the digitality of, for example, purple dragons. In fact, this illustration is material, digital, and textual all at once, since it has not been published in color — we only know the dragons are purple because the text tells us so.

Millet's novel — that is, the fictional narrative plus the photographic illustrations — requires a reading practice attuned both to medium specificity and to the mixing of media on the page. And in this case, the narrative text, the photographic illustrations, and the book in the reader's hands each register a distinct temporality. This interweaving of photography and narrative might sound like W. G. Sebald's writing, but Sebald's photographic and narrative temporalities tend towards the melancholic — they are both oriented to the historical past.2 The narrative, photographic, and readerly timescales in Mermaids in Paradise all contradict one another, and thus exemplify how contemporary novels address the multiple, often discordant, sometimes unimaginable timescales contained in our present. While Sebald's use of photographs creates a sense of dissonance between fact and fiction (his books lie somewhere between novel, memoir, and history), Millet's novel appears to be a work of comic realism (plus mermaids) until it swerves in its last few pages to become a work of speculative fiction about climate change and species extinction. Contemporary novels like Millet's have begun to use photographic illustrations to stage the clashing temporalities of environmental catastrophe. I do not intend to argue that the category of speculative fiction should be expanded to include Mermaids in Paradise and other recent novels with photographs, such as Ben Lerner's 10:04 (2014), Sara Baum's A Line Made by Walking (2017), and Valeria Luiselli's Lost Children Archive (2019), or other recent novels to play with contradictory timescales, such as Kate Atkinson's Life After Life (2013), Richard McGuire's graphic novel Here (2014), or Colson Whitehead's The Underground Railroad (2016). Novels with photographs are not necessarily works of speculative fiction; rather, they are works that require a speculative reading practice — a mode of reading that is, in other words, conjectural, risky, and attuned to the visual.3

Specifying the timescale of the narrative text in relation to the photographs' timescales and the reader's present requires a bit of plot summary. Chip and Deb, newly-wed and on their Caribbean honeymoon, go snorkeling with a parrot-fish expert, spot mermaids, and are caught up in corporate attempts to monetize the mermaids. There's a murder, a few kidnappings, a run-in with the Virgin Islands National Guard and another with a toe fetishist. There's a Japanese VJ, an ex-Navy SEAL, a vegan with a violent-crime phobia, and a "failed academic" who claims those two words are redundant. Incidentally, she has tenure in American Studies (17). Together, this team attempts to give the mermaids protected status as indigenous people. When the attempt fails, they combat corporate malfeasance as well as a storm of anti-mermaid sentiment on social media. Lydia Millet has been called "The P.G. Wodehouse of environmental writing," and with only two pages to go in the book, we learn that a large asteroid is about to hit the earth, that all the characters know if humanity had only come together and acted in time they could have altered its course, but now the end of the world is blazing across the night sky.4 Using the euphemistic language of government reports, Deb refers to this as "the extinction event" (288). For readers, the experience is one of getting hit over the head with an allegory rather than an asteroid.

Critics interested in novelistic temporality in relation to environmental catastrophe often bring eco-criticism or risk criticism together with genre studies. Amitav Ghosh goes so far in The Great Derangement (2016) as to claim that "serious fiction" — in other words, literary realism — is unable to imaginatively represent climate change.5 Millet's conclusion seems to lock her novel into the category of genre fiction even as she satirizes post-apocalyptic genre conventions: after all, the novel ends before the asteroid actually strikes. Jill Lepore has lamented in the New Yorker that recent dystopian fiction, such as Omar El Akkad's cli-fi American War (2017), seems to be a literature of political desperation rather than imagination: "It cannot imagine a better future," she writes, "and it doesn't ask anyone to bother to make one."6 If anything, Mermaids in Paradise is a pre-apocalyptic novel. Its satire links it to one of the literary genres Mark McGurl describes as "willing to risk artistic ludicrousness in their representation of the inhumanly large and long" (or in this case, willing to risk artistic ludicrousness by having an asteroid cut time suddenly short).7 The entirely plausible mermaids and asteroid also hint at science fiction, a genre whose temporal conventions begin to elucidate how the play of temporalities in Millet's novel work.8 The asteroid forecloses any future, so the narrative turns out to have been nothing but the present all along. Meanwhile, the allegorical import of the asteroid turns the reader's present into something like history, as in Fredric Jameson's well-known claim about science fiction's method.9 The narrative timescale is thus predetermined: it is the present as history of catastrophe. But scholars have recently begun to argue that climate fiction should not rely so entirely on forms of certainty like this. Rebecca M. Evans reads Kim Stanley Robinson's Three Californias trilogy (1984-1990) to argue for "partial, incomplete, and inconclusive apocalypses" that refuse such inevitability.10 And Jessica Hurley has shown that the "longue durée apocalypse" of nuclear waste can also be revolutionary: in Leslie Marmon Silko's Almanac of the Dead (1991) the future is so unimaginable it can also transform the present into "a speculative space," one that is equally open to imaginative transformation.11 The photographic illustrations in Millet's Mermaids in Paradise likewise counteract the narrative's closure, create openings in its present, and invite speculation about the future.

The timescale of the photographic illustrations extends beyond that of the narrative asteroid. Many of them, like the image of Chip and the dragons, depict annoyingly minor scenes. Two of them do depict mermaids, but not in the mode of a triumphant biologist presenting evidence of a new species or a social media post claiming #bestvacationever. Rather, like the rest of the images, they seem accidental, and they are all are held by the same well-manicured set of fingers. Deb's narration ends with her anticipating total destruction in a matter of months, but the illustrations emphasize that the material book has somehow survived. Thus the novel as a whole registers what Kate Marshall has described as contemporary fiction's "radically non-anthropocentric fantasy of extinction" in which a future non-human archeologist picks through the rubble of the planet, perhaps uncovering a few faded honeymoon snapshots.12 The illustrations insert a fantasy of photographic future retrospection into the novel, causing the here-and-now depicted by the photograph to clash with the future from which it might be viewed.13 Are those Deb's fingers? The reader's? An alien archeologist's? Each of these futures complicates the narrative timescale and its asteroid. Recent approaches to photography provide a new vocabulary for describing the temporal muddle that results from embedding photographs in fictional narratives. Rather than treating photographs as evidentiary or factual — as records of the past — many theorists now treat them as disclosive. That is, photographs actively reveal or teach viewers something about the world; they do not just capture a slice of it, freezing it in time.14 Reading for disclosure downplays the taking of the photograph and the authority of the photographer in favor of the photograph's ability to travel in time and encounter multiple viewers. Johanna Drucker describes this as "the unfinished-ness of photography."15 What photographic illustrations in contemporary literature can disclose is the speculative nature of reading for future retrospection, for futures that extend out of and beyond the fictional narrative.

The reader's experience of this novel — both the fictional narrative and the photographic illustrations — is shaped by disclosure. The narrative asteroid activates the most common definition of the term: making secret information known. But the photographs also register the etymology of the term "apocalypse," which is to uncover, to reveal, even to disclose. In a response to Lepore's essay on dystopian fiction, an author of a recent apocalyptic climate change novel offers a perspective based on this etymology: she advocates "trying to see how fiction in these genres uncovers or reveals the ways in which our society dreams — however darkly — of being changed."16 Staging clashing and multiple temporalities on the page teaches readers how to read speculatively, with an openness to future disclosure in all its forms. Thus the reader's present is the third temporal strand woven into the novel, because the clash between the temporality of the narrative and the temporality of the photographic illustrations — between the asteroid and the possibility of future retrospection — also invokes a particularly powerful definition of the contemporary in relation to the planetary damage Millet allegorizes. The contemporary is, etymologically, a coming together of multiple times and temporalities, and Dipesh Chakrabarty describes the "collision" of human and non-human histories and our inability to scale between their different temporalities as a large part of our current climate crisis.17Mermaids in Paradise stages this temporal clash on the page: the contemporary, in this novel, is a time of shared but discrepant temporalities and timescales in which multiple futures — both inside and outside the fiction — come to bear upon the reader's experience of the present. The juxtaposition of narrative and photograph is not a representation of the temporality of impending climate change and species extinction; it's a stage upon which readers must practice holding multiple, contradictory futures in mind at once.18

Fiction Meets Activism

What can this novel, or any work of fiction, offer environmental activism in a present bent on an asteroid-like trajectory towards future catastrophe? And what can the juxtaposition of image and text on the material page of the book offer readers in a remorselessly digital age? Jessica Pressman's exploration of an "aesthetic of bookishness" in post-2000 fiction insists that invocations of mixed media and digital technologies on the material page are not nostalgic.19Likewise, the clashing temporalities of contemporary fiction-with-photographs emphasize the practice of speculative reading in the present "real world" and suggest that learning to act in the face of the clashing temporalities of environmental catastrophe may take practice. Mermaids in Paradise does, in fact, have an embedded activist plot: the oddball team at the honeymoon resort tries to protect the mermaids using all the meager resources at their disposal. And they fail. The mermaids are saved, but not because of their efforts (more on this later). Yet the activists do not give up: their persistence demonstrates the difficulty of taking action in a present that anticipates the catastrophic futures of global warming and mass extinction. The disclosure of the asteroid does not motivate these activists — the shared fiction that they may have some agency despite the asteroid's imminence does.

The visuality of the novel also highlights a particularly acute dilemma of contemporary environmental activism. Absent an asteroid blazing across the night sky, picturing the multiple futures activated by our environmental crisis is difficult, if not impossible. Many critics have placed the famous photographs of earth from space, "Earthrise" (1968) and "Blue Marble" (1972), in genealogies of environmental awareness and activism. And yet reading these photographs as purely evidentiary is difficult because they have also been manipulated both imaginatively and technologically. Famously, they were imagined into existence by Stewart Brand before they were technically possible.20 And, while their depiction is seemingly objective and authoritative, it is also disembodied — a masculinist, "conquering gaze from nowhere" (in the words of Donna Haraway).21 They are also so inherently pictorially conditioned that, as Benjamin Lazier points out, when Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman spotted earth rising over the edge of the moon, he exclaimed: "Look at that picture over there!" before he even grabbed his camera.22 Eventually, both photographs' colors were enhanced and "Earthrise" was rotated to put the moon's surface in the lower foreground, conforming to the composition of a pictorial landscape. Novels with photographs encourage a reading practice open to disclosure, and in this mode the famous photographs of earth from space do not just provide evidence of the whole earth in all its majesty and fragility. They also invite speculation about the weave of facticity and fictionality inherent in the history of these photographs and the multiple futures — both catastrophic and activist — they contain.

Another common set of environmental images suggests the difficulty of such a speculative reading practice. Lydia Millet, who also works at the Center for Biological Diversity in Tucson, has herself criticized the photographs distributed by conservation organizations fighting species extinction. The photographs that tend to accompany paeans to vanishing species are invariably cute or majestic, the animals roaming sublime landscapes void of human population or shot in such striking close up that no human activity, let alone encroachment, is visible. Like the photographs of earth from space, photographs of these animals depend upon a disembodied gaze that is also wholly conditioned by human conventions of image making. In her 2004 polemic "Die, Baby Harp Seal!" Millet tells environmentalists that they "can no longer shrink from the rude, the vicious or the unsightly" — they need a tougher aesthetic.23 Yet she is well aware that extinction is hard to depict. Her trilogy on species extinction — How the Dead Dream (2008), Ghost Lights (2011), and Magnificence (2013) — describes "final animals" as "on the clock, in the long moment of going before being gone" and is dedicated to the West African black rhinoceros, which disappeared in the time it took her to write the first book.24 How to represent and picture "the long moment" before the end is a form of the unsolved problem in environmental activism that Rob Nixon describes as a "representational bias" against violence that is "neither spectacular nor instantaneous, but rather incremental and accretive."25 The unsightly, the un-spectacular, the prolonged, and the planetary are all at least as difficult to photograph as mermaids. The photographic illustrations in Mermaids in Paradise may seem evasive and deliberately un-spectacular, but they are in fact exasperatingly assertive. They assert both their fictionality and their material persistence into both the narrative's and the reader's future, thus capturing the clash of temporalities that characterizes environmental catastrophe.

Camera Meets Mermaids

Mermaids are mythological creatures, half fish, half human. Over the course of the novel, it becomes clear that Millet is less interested in their human aspects than she is in their status as sentient animals more or less indifferent to human activity. As soon as things begin to go wrong at the honeymoon resort in the British Virgin Islands, Deb notes: "When we'd arrived on the island, buffeted by trade winds and cradled by the white sands and all for a few weeks' pay, I'd felt like the American I was. It was a nice feeling, mostly. It had its minuses, sure (passivity, mental blankness), but also its pluses (vague background satisfaction caused by world dominance; non-starvation)" (124). When the corporate nets tighten, she will wonder if she is still American at all. The novel thus both satirizes the neocolonial Caribbean tourism industry and colonialism itself: at one point the parrot-fish expert explains that sighting the mermaids should be understood as meeting an "unknown tribe" (109).26 She phones a Berkeley anthropologist, a "first-contact scholar" (111), who is — no surprise — easily coopted by the resort's parent company (Millet's corporate villains). But the mermaids aren't creatures of human history, human myth, or Disney adaptation — they aren't seductive, they have no interest in becoming "part of our world," and while they do have long yellow hair, they also have bad teeth. "No underwater dentistry," Chip muses to himself (98). They're not photogenic, and they don't care for scuba divers with underwater cameras. Photographs of the mermaids do not conform to the scientific, conquering gaze of the camera eye or to the voluptuousness of Disney animation. The mermaids' indifference to the camera is similar, then, to the planetary damage that gives the novel its philosophical heft: neither photographs very well.

The view out the window from the room where Deb is held during her brief kidnapping

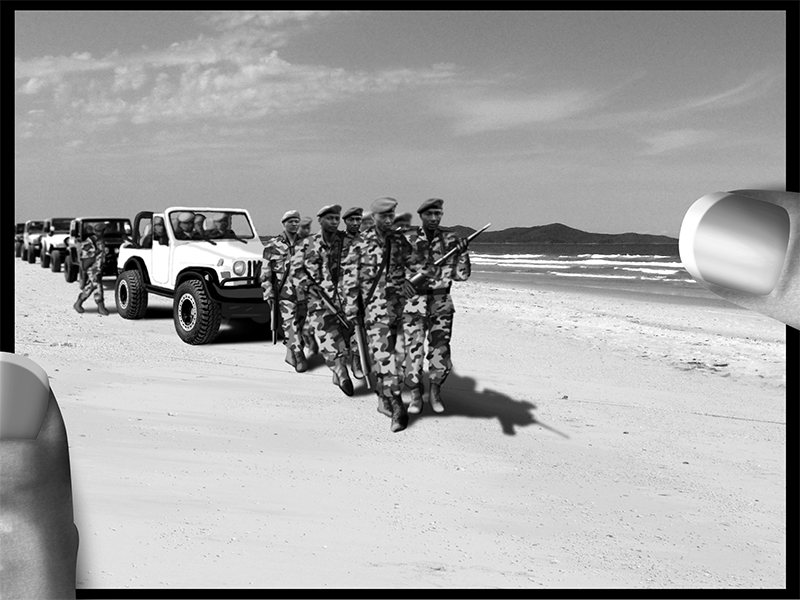

The frenzy on the pier as the resort's parent corporation assembles an armada of yachts, cranes, and nets.

Deb's narration of her honeymoon includes ten photographic illustrations, all of which appear accidental and amateurish. But in a narrative that includes a scathing depiction of social media frenzy, there are no selfies and no sunsets. The primary gesture to the genre of the social media feed is the sense that the photographer might be, as a critic of the Instagram aesthetic once put it, "oh so gently alienated."27 These illustrations are also tiny: you can't zoom in on them; you can't really "read" them. The concept for the illustrations was Millet's and the images are by Sharon McGill. They are a mix of stock photographs, hand-rendered drawings, and digital effects. To quote McGill, they are "laborious set-pieces made up of real and constructed imagery."28 Each image is held in what appear to be Deb's hands, and McGill used lighting effects in Photoshop to create her perfect manicure. Millet's initial idea was to include photographic illustrations snapped on a smartphone, and McGill composed the images within a smartphone frame. But because of the size and cropping of the publisher's final layout, the fingers appear to be holding prints — the absurdity of including printed illustrations of digital screens held by "real" fingers is partly obscured. But Millet suggested these illustrations so that they would cast doubt on the text and undermine the authority of the narrative voice — Millet likes their "impurity." She argues that introducing images into novels "brings more air and space into the narrative, into the reader's position in the narrative."29 In other words, images disclose the fictionality of the narrative at the same time that they foreground the practice of reading and open up space for the reader as a participant in that narrative. The uncanny overlap between the fingers holding the images and the reader's own simultaneously emphasizes and undermines their material reality.

The scare tactics of the parent corporation

There's something of P.T. Barnum's "Feejee Mermaid" in all this. In 1843, Barnum began showing a monkey's upper body sewn onto the tail of a fish and claiming it was a mermaid (though he admitted it was a diminutive and revolting specimen). Kevin Young has argued that the fact that its disappointing appearance looked nothing like the beautiful images used as advertisements was part of the pleasure for audiences: we enjoy knowing we've been fooled.30 This is as true for contemporary fiction as it was for Barnum's nineteenth-century "Humbugs & Curiosities." Like Barnum's mermaid, McGill's illustrations are hybrids: digitally rendered but also material and tactile in Deb's hands. And like the revolting photographs of Barnum's mermaid, McGill's photographs belie their own evidentiary value because what they disclose is our desire to believe in a fiction. It is not surprising, then, that McGill insists that as analog photographs many of these illustrations would be technically impossible. McGill digitally manipulates the image but leaves traces of that manipulation — the point is not that these photographic illustrations are hoaxes like Barnum's but that their evident fictionality draws attention to reading practices. Specifically, to readers' willingness to believe that a photograph might actually depict a scene or character we know to be fictional.

For example, the first of the two photographic illustrations that actually depict mermaids is a snapshot taken at a booze-soaked party where the only copy of the mermaid-sighting video is playing in a loop on the flat screen TV in the background. McGill used selective blurring in Photoshop: both the mermaid tail, which purports to be a photograph of a video, and the view out the back window are in sharp focus, but the party-goers in the foreground are not. In a technical sense, then, the illustration is, in McGill's description, "dreamlike and surreal,"31 and yet this video is the only evidence that the mermaids are, in fact, real. Deb admits that the mermaids "could have been CGI, fully," but then claims, "We knew it was real and there it was, exactly the way we'd seen it, in pixels and HD" (106).

The mermaid footage playing at the celebratory party

For Deb there's a satisfying feedback loop here between her first-hand experience and its visual representation, but for readers the feedback becomes deafening: we want to take computer-generated imagery as photographic evidence of the truth of a narrative we know to be fiction. The dissonance between fact and fiction, now overlaid with the dissonance between analog and digital media, directs readers' attention to how their reading crosses and re-crosses the line between what is inside the text and what is outside it.

The overlap of digital images and readers' actual digits on the material page discloses another layer of "impurity" beyond the conceptual and technical. The asteroid also renders these images illegible in time — it creates a clash of timescales inside the text that also defines the contemporary as it is experienced outside the text. The video that appears in the illustration described above is embargoed: everyone in the room has signed a waiver agreeing to keep the secret until the first-contact scholar arrives. Deb, however, snaps a photo on the sly, "for my records," she remarks (112). The inclusion of this illustration seems to allude to our desire to document every little thing, to curate our experiences for future consumption, either for our personal record or to share on social media. The chief temporal effect of these photographic illustrations seems at first to remind readers that no matter how out of hand this honeymoon caper gets, it's still a honeymoon undertaken in large part so that it can be remembered nostalgically. Even the occasional remarks about climate change and species extinction register as background noise in contemporary life: Chip and Deb encounter some "free-floating climate-change aggression" among their fellow tourists and mentions of rising seawater acidity and bleached coral reefs (75). Deb also falls into a reverie on the Great Acceleration, the "brief, screaming handful of seasons" during which humans have dramatically altered the planet's biogeochemical systems (281). The asteroid twist-ending makes the comic plot of the novel even more ridiculous: why get married and go on a honeymoon if you only have a few months left? Why, in this time frame, would the parent company seek to trap and monetize the mermaids? Why even take photos if there's no possibility of ever looking back on this trip?

Narrative Meets Asteroid

The photographic illustrations don't make much sense as evidence of mermaids or evidence of a memorable honeymoon. They seem to contain a fantasy of retrospection from an unspecified, post-asteroid future, and as such they create openings, or impurities, in the narrative in which they are embedded. In light of recent theories of photographic "disclosure" that allow images to be read for their futurity and not — or not just —their historicity, McGill's illustrations appear not just absurd or silly, but also earnest — capable, perhaps, of teaching readers how to live with the extreme closure of the asteroid within the fiction and with planetary catastrophe without.

Contemporary theoretical approaches to photography emphasize the medium, but unlike earlier twentieth-century criticism, they do not focus on photographic reproducibility or indexicality. Modernist paranoia about a mass culture of reproducible images — in, for example, the work of Walter Benjamin, Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag, Allan Sekula — has receded, replaced by a somewhat grim enthusiasm for photography in relation to new media, digital networks, and algorithmic processing. And in the first of her three-volume history of photography, The Miracle of Analogy (2014), Kaja Silverman remarks that because the photographic index points to what was incontrovertibly there, discussions of indexicality "always focus on the past."32 In order to focus on the future, theorists turn to the history of the medium to show how early photography was contradictorily imagined as both relational and nonhuman. In Silverman's emphasis on photographic "disclosure" over evidence of the world, disclosure is a relation, a summoning — a photograph is therefore not a fixed representation of the world, stilled in time. It can also solicit a response.33 In a far more political mode, Ariella Azoulay argues that the photograph should not be accepted as the singular, inevitable outcome of photography, nor should the photographer be accepted as sole authority over their image. In her curatorial work Azoulay intervenes in photographic images, recontextualizing them, even folding and unfolding them. In her critical writing she argues that the photograph is an invitation for more viewing, more reading, more "taking part in the production of its meaning."34 This focus on relationality and response may seem incompatible with theorists' view of photography as not wholly conditioned by human modes of perception. But even a nonhuman photograph can travel in time and make human meaning. Joanna Zylinska begins her book Nonhuman Photography (2017) with "imaging practices from which the human is absent — as its subject, agent, or addressee," such as algorithmic or computational photographs.35 But rather than elevating nonhuman photography as the key to contemporary media, she argues that all photography has been to some extent nonhuman. This fact, she argues, is liberating, because when vision is freed from "the constraints of the embodied human eye, with its established set of visual relations and the limited directionality of its outlook, a possibility arises of glimpsing another setup, or rather, of glimpsing it differently."36 This nonhuman glimpse afforded by the camera can imagine "another setup" of the future, which for Zylinska is part of photography's revolutionary human potential in the present.

The lessons here for reading photographs in novels are twofold. First, if you can suspend your inclination to read the photograph as evidence then you can read for a slower opening, a disclosure that takes in the experience of seeing as well as what's seen — a disclosure that countenances other participants in that seeing. Second, if you can shift your temporal understanding of the photograph away from the idea that it captures or freezes a moment in the past, then you can see the multiple, unrealized futures it contains, and you can speculate about undetermined, alternative futures that might yet unfold. Recent theories of photography do not deal with photographs when they appear within novels, and they therefore seem to privilege the visual over the narrative. But the "if/then" constructions above are not statements of cause and effect, they are descriptions of method, and they are directed at "you," the reader. Reading photographs for the future from within a comically foreclosed narrative is how Mermaids in Paradise generates the temporal clash of the contemporary for its readers, whose future is also seemingly fixed, though not so immediately nor so comically.

The theories of photography outlined above also suggest that contingency is a key term for understanding the clashing temporalities of novels with photographs and the risky practices of speculative reading they encourage. Whereas photographic contingency has long been located in the past — the photograph freezes what was ephemeral, accidental, fleeting — in the novel with photographs contingency shifts to the future.37 And yet, placing photographic contingency in the future, as an event or circumstance that cannot be predicted with certainty, emphasizes possibility but resists prescriptive meaning or content — the photograph tells us nothing about how the future will be or how we should act now to ensure a future we want.38Does some unforeseen contingency slightly alter the asteroid's trajectory? Do these photos actually survive? Will this honeymoon be fondly remembered? It hardly matters; these photographic illustrations prompt reading practices open to alternative futures, because by the end of the novel readers must hold multiple futures in mind at the same time: the fictional asteroid's destruction of the planet alongside the possibility of the characters' survival and the environmental catastrophe of climate change alongside the possibility of our own survival.

The photographic illustrations in Mermaids in Paradise thus emphasize certain aspects of comedy — incongruity and transformation — over others, such as resolution. Ursula K. Heise, exploring the role of comedy in imagining and depicting species extinction, writes: "Only occasionally has conservationist writing mobilized the resources of comedy . . . [which] emphasizes contingency and improbable modes of survival over predictability and extinction and thereby opens up different cognitive and emotional attachments to the lives of other humans as well as nonhuman species."39 But, as I will show with a final photographic illustration, Millet seems to guard against letting the comic clash of photographic and narrative temporalities spur ethical action or offer the comfort of affective relief. Her novel may instead participate in the comedy of scale McGurl has termed "posthuman" and outlined in relation to "gigantic realism," dark humor, minimalism, and horror.40 In Millet's novel, an unexpected event does, in fact, occur, and the mermaids are rescued from the machinations of the parent company, though not from the approaching asteroid. Deb and her fellow mermaid activists are on the open water, attempting to bring the full force of the British Virgin Islands' bureaucracy to bear upon the mermaid armada (there is talk of required fishing permits), when Deb has what seems to be a panic attack and, in her words, "over-identifies" with the mermaids. She feels the water around her and the nets tightening, but what she thinks about is time: "It's only been days, I thought, a handful of days after probably tens of thousands of years we must have lived in parallel — we stumbled across them, we filmed them, and now their enemies are legion" (260). Deb is grieving, in Lesley Head's sense of the term. Head describes grief as a part of the cultural politics of climate change: "this is grief for what we understood as our future — hitherto a time and place of unlimited positive possibility."41 But Deb's personal, bodily over-identification is interrupted when something unexpected, even impossible, occurs: blue whales, swimming uncharacteristically close to shore in a large group, appear, collect the mermaids, and allow them to ride to safety on their backs and tails. The last photographic illustration in the novel depicts this scene (it also appears tipped at a jaunty angle on the title page).

The mermaids' final escape from the parent corporation's armada.

Fittingly, this image is annoyingly inaccessible to the reader's eye. It's too small, and the mermaids are practically invisible on the whale's barnacle-encrusted tail. It's not possible for readers to "over-identify" like Deb, who later manages to reflect upon the non-anthropocentrism of the mermaids' rescue: "They saw what we were, those whales, and wanted nothing to do with it" (273). Likewise, while readers may see their own fingers overlapping with the fingers holding the images, it is not possible to "over-identify" here: the interposed fingers should also be seen as intensely alienating, like Deb's final, bleak view of the whales. However, just as theorists of photography simultaneously hold out the medium's nonhuman aspects as well as its human relationality, the speculative reading practice encouraged by photographs embedded in contemporary fiction illustrates the weave of personal and planetary — or human and nonhuman — perspectives necessary in such a practice. Despite the human fingers holding the images, both the mermaids and the whales are wholly indifferent to human identification, empathy, or interference, and so is the camera.

Head argues that grief can still coexist with hope, as long as hope is understood to savor "the life and world we have, not the world as we wish it to be."42 This, too, seems to be Millet's conclusion. In the last pages of the novel, Deb takes the time to explain why she agreed to the honeymoon and why she might have been snapping pictures throughout. She says: "When it came to the future, we all acted as if. Only way to proceed, said Gina firmly, and Chip and I agreed" (289). Gina's lesson is that the whole narrative has been an "as if" premised upon an impossible future. Hope can be a practice, rather than a progressive narrative or an emotion, and it is a critical-speculative practice — Gina is an academic, after all. Her reading practice is not unlike the one McGurl notes, bleakly, in his summary of critical approaches attending to the inhuman scale of geologic time and environmental catastrophe: "In the work of the new cultural geology, even in its gloomier modes, there is a widespread sense, if not of hope, then at least of an opening, a breach. Who knows but that what arises from that rubble might not be better than what we have now? — before someday most likely becoming incomparably worse."43 Here the opening, breach, or disclosure does not comfort readers or help the narrative progress to a specific future, but it does offer a speculative reading practice at work in the here and now. Mermaids in Paradise is not a "what if" story about an asteroid strike — it's not Michael Bay's Armageddon (1998).44 It's an "as if" story that includes hope for the future as well as despair. This view handily echoes the epilogue of H.G. Wells's The Time Machine (1895), where the narrator both accepts and refuses the dystopian future the Time Traveler has recounted: if that future is so, the narrator concludes, "it remains for us to live as though it were not so."45 As if, as though — this is the speculative temporality of photographs when they appear in contemporary fiction, materializing our contemporary as a composite of clashing timescales and multiple futures.

Emily Hyde is an assistant professor of English at Rowan University where she is completing a book titled A Way of Seeing: Postcolonial Modernism and the Visual Book that examines the global forms of mid-20th-century literature through the vexed status of the visual. Her articles and reviews on comparative modernisms, postcolonial literature and theory, and contemporary literature and photography appear in PMLA, Literature Compass, Comparative Literature Studies, Public Books, and Post45:

References

- Lydia Millet, Mermaids in Paradise (New York: W. W. Norton, 2015), 31. Hereafter cited in the text. Images courtesy of Sharon McGill.[⤒]

- Sebald's books The Emigrants, The Rings Of Saturn, Vertigo, and Austerlitz, all translated into English between 1996 and 2001, are a kind of enigmatic apotheosis of the history of novels with photographs. The high points of that history begin on the deserted streets of Georges Rodenbach's Bruges-la-Morte (1892), then move to the modernist experimentation and convulsive beauty of Virginia Woolf's Orlando (1928) and André Breton's Nadja (1928) before reaching Sebald and the present. Two resources for the history and range of novels with photographs include Jim Elkins's website Writing with Images and Terry Pitts's blog, Vertigo.[⤒]

- Etymologically, "speculate" comes from Latin speculat- "observed from a vantage point," from the verb speculari, from specula "watchtower," from specere "to look."[⤒]

- Laura Miller, "The P.G. Wodehouse of environmental writing: Why Lydia Millet is the funniest literary writer you may never have read," Salon.com, November 23, 2014.[⤒]

- Amitav Ghosh. The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 24. For more genre approaches, see Mark McGurl's recent work on the generic contours of what he calls "posthuman comedy" and Ian Baucom's analysis of the non-linear plot structure and resulting "character development" of Sonmi-451 in David Mitchell's Cloud Atlas (2004). Mark McGurl, "The New Cultural Geology," Twentieth Century Literature 57, no. 3/4 (Fall 2011): 380-90; "Ordinary Doom: Literary Studies in the Waste Land of the Present," New Literary History 41, no. 2 (Spring 2010): 329-349; and "Gigantic Realism: The Rise of the Novel and the Comedy of Scale," Critical Inquiry 43, no. 2 (Winter 2017): 403-430; Ian Baucom, "'Moving Centers': Climate Change, Critical Method, and the Historical Novel," Modern Language Quarterly 76 no. 2 (June 2015), 137-57. For more on the contemporary novel and climate change, see the special issue "The Rising Tide of Climate Change Fiction," edited by Stef Craps and Rick Crownshaw, Studies in the Novel 50, no. 1 (Spring 2018). For recent work on poetry and climate change, see Margaret Ronda, Remainders: American Poetry at Nature's End (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2018).[⤒]

- Jill Lepore, "A Golden Age for Dystopian Fiction," New Yorker, June 5 & 12, 2017.[⤒]

- McGurl, "The New Cultural Geology," 539.[⤒]

- The asteroid is so timely and plausible that Simon & Schuster has just released a pop science book on the topic. See Gordon L. Dillow's Fire in the Sky: Cosmic Collisions, Killer Asteroids, and the Race to Defend Earth (New York: Scribner, 2019).[⤒]

- Fredric Jameson, Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions (London: Verso, 2005), 288.[⤒]

- Rebecca M. Evans, "The Best of Times, the Worst of Times, the End of Times?: The Uses and Abuses of Environmental Apocalypse," ASAP/Journal 3, no. 3 (September 2018), 503.[⤒]

- Jessica Hurley, "Impossible Futures: Fictions of Risk in the Longue Durée," American Literature 89, no. 4 (December 2017): 761-789. Hurley argues that "In Almanac of the Dead, the presence of nuclear waste introjects a deep-time perspective into the contemporary United States, transforming the present into a speculative space in which environmental catastrophe produces not only unevenly distributed damage but also revolutionary forms of social justice that insist on a truth that probability modeling cannot contain: that the future will be unimaginably different from the present, and the present, too, might yet be utterly different from the real we think we know" (762).[⤒]

- Marshall's examples are not photographic, but they are graphic. See Kate Marshall, "What Are the Novels of the Anthropocene? American Fiction in Geological Time," American Literary History 27, no. 3 (Fall 2015): 525. For more on retrospection and the scaling up of memory studies, see Lucy Bond, Ben De Bruyn, and Jessica Rapson's special issue "Planetary Memory in Contemporary American Fiction, Textual Practice 31, no. 5 (2017).[⤒]

- For more on the affective quality of the here-and-now in relation to its futures, see Elias, who recommends thinking of the future as "slipstream": "We look forward in time almost against our will, in the wake of a future understood to be antithetical to reason, out of control, or operating outside of human agency." Amy J. Elias, "Past/Future," in Time: A Vocabulary of the Present, ed. Joel Burges and Amy J. Elias (New York: NYU Press, 2016), 41.[⤒]

- See Kaja Silverman, The Miracle of Analogy or The History of Photography Part 1 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2014) and Ariella Azoulay, who argues that "photography is not a record but a site of action" in "Photography Consists of Collaboration: Susan Meiselas, Wendy Ewald, and Ariella Azoulay," Camera Obscura 91, vol. 31, no. 1 (May 2016), 198.[⤒]

- Johanna Drucker "Temporal Photography," Philosophy of Photography 1, no. 1 (Spring 2010), 28.[⤒]

- Megan Hunter, "Seeing the Hopeful Side of Post-Apocalyptic Fiction," Literary Hub, November 8, 2017).[⤒]

- See Osborne, who defines the temporal quality of contemporaneity as "a coming together not simply 'in' time, but of times. Peter Osborne, Anywhere Or Not At All: Philosophy Of Contemporary Art (New York: Verso, 2013), 17; Dipesh Chakrabarty, "Climate and Capital: On Conjoined Histories," Critical Inquiry 41, no. 1 (Autumn 2014), 1. Although McGurl sees culture as newly aware that it exists in "a time-frame large enough to crack open the carapace of human self-concern," other theorists see art, in particular, as registering not geologic timescales so much as shared human timescales across cultural difference. See McGurl, "The New Cultural Geology," 380; Okwui Enwezor, "The Postcolonial Constellation: Contemporary Art in a State of Permanent Transition," Research in African Literatures 34, no. 4 (Winter 2003): 57-82; and Terry Smith, who argues that the contemporary "signifies multiple ways of being with, in, and out of time, separately and at once, with others and without them" in What Is Contemporary Art? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 6.[⤒]

- Jessica Hurley and Dan Sinykin make a similar point, proposing that apocalypse is "never a locatable event but rather an imaginative practice that forms and deforms history for specific purposes: an aesthetic that does as much as it represents." See their "Apocalypse: Introduction," ASAP/Journal 3, no. 3 (September 2018): 451.[⤒]

- Jessica Pressman, "The Aesthetic of Bookishness in Twenty-First-Century Literature," Michigan Quarterly Review XLVIII, no. 4 (Fall 2009).[⤒]

- See Lazier, who notes that "In 1966, a young activist and LSD enthusiast named Stewart Brand peddled buttons inscribed with the question "Why haven't we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?" He hoped the view would work as a hit of cultural acid, a trip he helped abet with the cover of his Whole Earth Catalog. Brand's expectations were vindicated." Benjamin Lazier, "Earthrise; or, The Globalization of the World Picture," The American Historical Review 116, no. 3 (June 2011): 602-630.[⤒]

- Donna Haraway, "Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective," Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (Autumn 1988): 581. See also Stacy Alaimo, Exposed: Environmental Politics and Pleasures in Posthuman Times (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), and Thomas M. Lekan, "Fractal Eaarth: Visualizing the Global Environment in the Anthropocene," Environmental Humanities 5, no. 1 (May 2014): 171-201.[⤒]

- Lazier, "Earthrise," 606.[⤒]

- Lydia Millet, "Die, Baby Harp Seal! It's Time for Environmentalism to Get Ugly," High Country News, April 12, 2004.[⤒]

- Lydia Millet, How the Dead Dream (Berkeley: Counterpoint Press, 2008), 97.[⤒]

- Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), 2, 13. For a range of recent exhibits of future-oriented environmental photography unrelated to novels, see Ella Mudie, "Beyond Mourning: On Photography and Extinction," Afterimage 44, no. 3 (November/December 2016): 22-27; and Aperture's special issue #234 "Earth" (Spring 2019).[⤒]

- Deb's comments also gesture towards the critical debate between thinking of climate change as a catastrophe for humanity as a whole and thinking of it in relation to specific histories of colonialism, inequality, and capitalist expansion. For more, see Ghosh, The Great Derangement; Dipesh Chakrabarty, "Anthropocene Time" History and Theory 57 (March 2018): 5-32; and Ian Baucom, "History 4°: Postcolonial Method and Anthropocene Time" Cambridge Journal of Postcolonial Literary Inquiry 1, no. 1 (March 2014): 123-142. For a postcolonial take on mermaids, see Kei Miller's poem "The Law Concerning Mermaids," The Missing Slate, June 1, 2014.[⤒]

- Choire Sicha, "Your Beautiful Pictures Are Stupid: Against Trendy Digital Photography," The Awl, October 5, 2010.[⤒]

- Sharon McGill, email correspondence, December 3, 2017. [⤒]

- Lydia Millet, email correspondence, December 4, 2017.[⤒]

- Kevin Young, BUNK: The Rise of Hoaxes, Humbug, Plagiarists, Phonies, Post-Facts, and Fake News (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2017), 7-8.[⤒]

- McGill, email correspondence, December 3, 2017.[⤒]

- Silverman, The Miracle of Analogy, 2.[⤒]

- Ibid., 159.[⤒]

- Ariella Azoulay, "Potential History: Thinking through Violence," Critical Inquiry 39, no. 3 (Spring 2013): 556. See also Ariella Azoulay, Civil Imagination: A Political Ontology of Photography (London: Verso, 2012) and Ulrich Baer, "Seeing the Future in an Image from the Past: Hannah Arendt, Garry Winogrand, and Photographing the World," The Yearbook of Comparative Literature 55, no. 1 (2009): 263. Baer reads civil-rights era news photographs with and against Hannah Arendt in this article and in "The Less-Settled Space: Civil Rights, Hannah Arendt, and Garry Winogrand," Aperture 202 (Spring 2011): 62-65.[⤒]

- Joanna Zylinska, Nonhuman Photography (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017), 5.[⤒]

- Ibid., 101.[⤒]

- This is not the same as Walter Benjamin's "tiny spark of contingency, of the here and now," which flares out of the photograph in order to be recognized by future viewers. That spark is redemptive, in that the past of the photograph and the present of viewing come suddenly together, electrifying the future with possibility. The Benjamin of the "Little History of Photography" — where the "tiny spark" appears — is the patron saint of Silverman's recent work, whereas Azoulay, Baer, and Zylinska's interests in photographic futurity are less grounded in the philosophy of history than in the practice of politics, in, as Azoulay puts it, "a certain form of human being-with-others in which the camera or the photograph are implicated" (Civil Imagination, 18). Novels with photographs are likewise more interested in practice than in the messianic. See Walter Benjamin, "Little History of Photography," Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, Vol. 2 1927-1934, trans. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005), 510. For the preeminent theorist of past photographic contingency, see Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981).[⤒]

- For a very different view of photographic futurity, see Vilém Flusser, "Photography and History" in Vilém Flusser: Writings, ed. Andreas Ströhl, trans. Erik Eisel (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), 126-31. Flusser argues that "Photographs are programmed to model the future behavior of their addressees" (130). For a reading of the ethics of futurity in contemporary literature, see Amir Eshel, Futurity: Contemporary Literature and the Quest for the Past (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).[⤒]

- Ursula K. Heise, Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 14.[⤒]

- See McGurl, "The New Cultural Geology;" "Ordinary Doom;" and "Gigantic Realism." For more on dissident environmental affects such as irreverence, frivolity, indecorum, and playfulness, see Nicole Seymour, Bad Environmentalism: Irony and Irreverence in the Ecological Age (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), 2018.[⤒]

- Lesley Head, Hope and Grief in The Anthropocene: Re-conceptualising Human-Nature Relations (New York: Routledge, 2016), 21.[⤒]

- Ibid., 28.[⤒]

- McGurl, "The New Cultural Geology," 389.[⤒]

- Not even close: it has been optioned for film with Jonathan Krisel of Portlandia as the director.[⤒]

- H.G. Wells, The Time Machine (London: Oxford University Press, 2017), 87.[⤒]