Someone Else's Object

A Palimpsest of Returns

In July 2017, I accompanied twelve students from Oregon State University to Cuba on a study abroad trip. It was also my first trip to Cuba, a place I had studied, a place my father and his family call home, a place where my grandfather died after fighting in the Bay of Pigs, a place that has haunted my imagination and my dreams for years. Though I felt ill-equipped, in truth I had long prepared for this very trip that in many ways felt like a return. There, I found myself strewn between the need to hold myself together as an adult, a queer, and a feminist, to pursue my own research interests, to wrestle with my family's fraught past there, and to maintain my role as a teacher. I worried that my trip to Cuba would confirm my fears of un-belonging — with one mispronounced word, I could be found out, then cast out. Yet, once in Cuba, I found less a sense of origin and more a matter of place. I encountered a rich, entangled history where my own thread in the strange weave of my lineage became less speculative and more piqued.

During this trip, I paid homage to Ana Mendieta's existing work in Jaruco, Cuba: the Esculturas Rupestres which she carved into limestone cave walls in the summer of 1981. Once considered eroded and lost by the Guggenheim and Ludwig Foundations, Mendieta's sculptures have since been relocated and at least this chapter of her artistic legacy has been re-written.1 These sculptures have remained obscured by the chasm that separates Cubans from one another. Mendieta went back to Cuba from the U.S. to make these carvings, and did so with equal parts trepidation and bravery. She too worried over whether or not she belonged there, but she also defied the very ideology that rended her from her home: that made belonging an impossibility in the first place. Mendieta's trip home spurred many returns in her wake — followers who search for traces of her labor in stone, who were emboldened by her own return outside of official discourse and into the matter of the land itself. This land is mined with the violence of colonial contact, forced enslavement, indigenous decimation, and a whole history of dissident resistance.

After my trip to Cuba and Jaruco, I caught the Mendieta detective bug. Spurred by the encounter with her fading, limestone sculptures, I recalled that when Mendieta returned from her trip to Cuba in 1981 she made several pieces in Miami. It is both a comfort and a jolt to arrive in Miami after being in Cuba a mere 40 minutes prior. The trip is a quick ascent, a level flight for a breath, and a dashing descent. Such a trip, for any Cuban, often requires a transition period to a new kind of mourning, a new reckoning with what has (yet again) been left behind, but also what experience has been integrated anew. These trips rearrange one's psyche and the process of growth or evolution is not so much pleasurable as it is vital.

In Miami, Mendieta found various locations to produce some of her most iconic Siluetas —empty outlines of corporeality that sometimes look like a goddess and sometimes like the taped outline of a crime scene. She pulled and tugged at that tension between reverence and violence — a signature of her work which found force in the matter of blood, stone, and fire. In October of 1981 on Key Biscayne, Mendieta created Ochún: two ridged lines of sand, sculpted on the shoreline with a tapering negative space inside the vaguely vaginal abstraction turned channel.

(© The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.)

A silueta of the Santería deity, who symbolizes rivers and who is the daughter of Yemaya, her oceanic provenance, Ochún syncretically correlates to La Virgen de Caridad del Cobre, the patron virgin of Cuba, who watches over those who brave dangerous waters. A mere ninety miles separate the tip of the Florida Straights and Cuba, though many have been engulfed psychically and physically in that oceanic chasm. Ideologies, race, and possibilities are radically different on either shore. Along these shorelines, Mendieta develops two lines undulating to form the abstracted contours of something like a body made of the sand from Miami that with each wave is pulled in and carried back to Cuba. The silueta sands act as particulate prayers, as tiny emissaries and intricately granular forms of relation. This ephemeral sand performance was filmed and so remains at least hauntologically traceable visually and in the imagination, a reminder of the waters that threaten to erode but also unite.

(© The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.)

Mendieta made Ceiba Fetish in Calle Ocho — a concentration of Cuban restaurants, shops, and the iconic domino park in Little Havana that runs along SW 8th St. In the heart of Calle Ocho sits the Cuban Memorial Park that juts perpendicular off 8th with blocks of lush green studded with homages to Cuba. Today, if you go, the first thing you will see is an eternal flame for Brigade 2506 — the mostly Cuban, CIA-trained men who plotted and attempted a coup d'etat of Fidel Castro's regime in 1961 through what official United States discourse calls the Bay of Pigs (and a fiasco) and what Cubans on the island call Playa Girón (and the first Latin American triumph over US imperialism).

Between the bay and the beach, a gulf of mistranslation separates the inhabitants of greater Cuba from one another. This early attempt at overthrowing the populist revolution sedimented many things: the notion of the first Latin American victory over United States imperialism and intervention, the classification of dissident Cubans as gusanos or worms that rot the Revolution, the ossification of the divide between exiles and those on the island, as well as the swift rise of Cuba's position in the Cold War. Many argue that the failed invasion further aligned the Soviet Union and Cuba, resulting in the Cuban Missile Crisis just a year later in 1962. But for my family and for my father, it marked the death of a great military hero. The death only known as death, when my abuelo did not descend from the planes with over a thousand Bay of Pigs prisoners released by the Cuban government on December 24th, 1962 — a release made in exchange for 2.5 million dollars worth of medical and food aid from the United States government. My grandfather, instead, returns only in name and mythos.

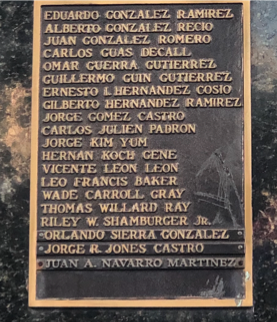

The Brigade 2506 monument is formidable and militant in trope and design. A marble base extends upward from the ground as an obelisk, gleaming with shined granite, and surrounded by missile heads, all encased in chains. The names of those who died on the shores of Playa Girón are on each facet of the obelisk on bronze plaques, a mineralogical, different kind of stone writing than the cave carvings in Jaruco. My grandfather's name lives on one of these official, proper plaques that faces southward down the park, gazing at ceiba trees, flamboyán trees, a bust of José Martí, and an image of the Cuban island which so many refuse to return to physically, but to which they remain melancholically attached. Mendieta mourned in her artistic practice, but her relation to loss did not take the past within and freeze it. Rather, she externalized and figured her relation to the past through abstract lines that matched the contours of her canvas. The past was her matter and medium, but not her property.

With my two primos, we walked through the park, pausing to pay our respects with our silent gaze over the brass, embossed name of our grandfather: Vicente León León, my own father's namesake. Yet, the plaque reads "Vicente Leon Leon," sin accento, evidence of the fact that we were indeed in the United States, a country that often, and certainly bureaucratically, has a monolingual English approach that yields my own last name as a first name: Leon. We said nothing to one another at this monument because the whole of our lives had already been replete with the story of the death of our grandfather, a person we never met who nevertheless lingered heavily over our family. We moved along. We strolled two blocks from the memorial flame to look for Mendieta's Ceiba Fetish. In addition to the flamboyán trees which emit red sparks of flowers that light up the sky, two other, very differently Caribbean trees populate the park: ceiba trees.

Ceiba trees hold a special place in Latin American plazas across the hemisphere and, in Cuba, they are often considered sacred. One ceiba tree holds court over the park and its visible roots gesture toward the embrace of a statue of the Virgin Mary, with jutting roots that refuse to be contained underground, bulbous knobs that protrude from the tree's bark, and a trunk that seems to have twelve legs coming together toward an approximately six foot diameter. With pictures for reference, I scouted the two ceiba trees I encountered looking for even a trace of the black paint she used to create Mendieta's silueta. It took me a few circlings to find my reference point: three bulging knobs that were just to the left of Ceiba Fetish in 1981.

What I didn't expect was that the tree would require an approach, its roots extending outward in a way that makes the ground an uneven set of divots. Collected in the small valleys of roots and palm fronds was the detritus of the homeless in the area: plastic bags, cans, shit, and the empty encasings of thrown away food. The refuse of the refused laid at the base of this sacred tree.

From afar I could see one extant line, painted in black: the quivering line that has survived thirty-eight years on this tree. And, to my astonishment, atop a wooden protrusion sat a little velita: a prayer candle in blue, the color for Yemaya who is Oshún's mother and goddess of the ocean.

Word has it that when Mendieta first made Ceiba Fetish, santería practitioners believed it to be an apparition of a goddess, or a silhouette of La Virgen. And so, they brought offerings to this tree which Mendieta blessed and which she would have known was always a sacred tree, the kind of tree that demands homage and gifts. How do I even begin to read the perspective and alignment of these two spectral figures, Ana Mendieta and my abuelo, who have constituted my own psychic relation to Cuba for so long? One hides in plain sight with no official, proprietary signifier, while the other enjoys the memorialization of the polished brass name, or misname, on a plaque with the promise of an eternal flame.

Bloodlines: When Things Line up After Loss

Every era has theoretical nervous tics — spun out symptoms of theory both under-read and over-trending. During my critically nascent years everything was being queered — time, space, tables, literature, Jane Austen, Greek history (or not) — nothing was straight. This was a time of paranoid reading that lead to endless queerings. Since nothing is really straight or linear, save for Euclidean geometry, it became easy with a few small flips of a prioris to show that something wasn't as straight or linear as it purported to be. But this move required a naïve victim of false consciousness, the tragically heteronormative view that time and things were linear, progressive, and teleological. The aim was to dispel faith in the reigning order, in the belief that time alone would bring about change.

But sometimes things line up, come into view in a perspective that draws them near if not symmetrical, teleological, or analogical. I mean the besideness that Sedgwick offers as a relational, spatial tethering that might be circumstantial and might be more.2 Tracing a line of connection means being attentive to the ways in which we learn by the texture of relation, through enfolding and entanglement in space and time. A novel pairing, upon examination, yields so much by mere chance and juxtaposition. This way of things lining up doesn't yield a teleological trajectory so much as a relational immersion, nearly imperceptible ties that bond.3

The mystery of Mendieta's death is, for many of us, not a mystery at all. We, those of us who follow her legacy beyond her death, know that the blood poured on any museum which deigns to exhibit Carl Andre carries with it a guilty sentence, even if the law excused murder. We know what happened. The mystery is that business goes about as usual after a massive crime has been committed. The mystery is that a predictable, pathetic, and weak misogyny still rages, and rages all the harder against people of color and of marginalized genders. And in this constellation of power and precarity, one cannot help but think of the countless queers who adored Mendieta and lost so many of their loved ones in New York during the decades of the eighties and early nineties.

Why do so many queers follow Mendieta after her death? We "other" Cubans have two iconic Josés who follow her: José Esteban Muñoz and José Quiroga, brother aesthetes in the ongoing story of cubanidad, diaspora, and loss.4 And in the wake of the too soon loss of Muñoz, his queer kin rallied with his own words, and particularly his own words about the after-burn of Mendieta.5 We queers are accustomed to a line-up of loss — of a person, a home, a place — that comes too soon. Death in the early eighties in New York City had a larger body count than one. Mendieta's work speaks to us, precisely as that which trafficked in the unofficial, unmarked histories that she unearthed with her siluetas as homages, rather than claims or proprietary relations to the land, to peoples, to cultures.

Proper names find loose interpretation in Mendieta's sculptures and performances. Ochún looks more like the sculpture of a mystical and aesthetically inclined sand rodent than representations of the orisha that bears her name. So too did Mendieta indulge in her own loose bio-mythos, working alone in the elements and relating tales of dark magic that came from some of her works. I think of the ludic mythologies that Mendieta made about herself, immersed as she was in cosmological fantasies and creative myth. Though her great uncle, Carlos Mendieta, was the president of Cuba in the thirties (with, ironically, Fulgencio Batista at his side), many early biographers noted him as her grandfather. The mythologies surrounding Mendieta fluctuate with her dynamic, ephemeral art. While she worked with iconography, she was not an initiant of Santería or Regla de Ocha. But she often claimed that some of the works that employed such iconography would go awry and she worried, as we all do, that she was working with matter she should not have. But all of these ephemeral recordings, fleeting earthworks, and unfaithful translations have less to do with a lack of rigor and more to do with the process of exile.

Why do we scramble to find ruin? What is so fascinating about a line of paint on a tree in a park? Rather than a metaphysics of presence, we are asked to witness differing temporal registers and fades and absorptions that show the ecological interplay between human hand and natural formation. A silueta made in the sand will vanish relatively quickly, as the lapping waves pull grains of sand undertow, into the swirl, to surface in foam, or pull perhaps a few bits back to Cuba but more likely to dance in swerves across the Caribbean. What has this errant pursuit of Mendieta meant for me? Perhaps it is simply akin to what it's meant for others, that the very materiality of the search takes one outside of oneself — ecstatic at the glimpse that a mark in a difficult atmosphere or environment has not yet been erased, especially since at some point it certainly will. If very little survives eons of deep time, Ceiba Fetish, as well as the sculptures in Jaruco, will not last — they too will be lost.

And what comes after loss?6 What comes after a loss I never experienced when that loss was the source of my being in the world — the very geopolitical forces that disenfranchised so many but that also formed a matrix wherein I could be born into a fraught, bicultural home in central Florida? How can I express that my sense of cubanidad only came to me after I came out to my father as queer, dashing his dreams of an upstanding, morally unblemished progeny to compensate for the loss of his father, his patria, and his hopes for this exile? What does any of this have to do with a Cuban artist who made sculptures in a remote park of Cuba the same year I was born in Lakeland, Florida? And how can I hold both Mendieta and my grandfather, both my feminism and my family, in the same psyche?

Melanie Klein reminds us that the whole object is made of partial, fragmented, and often competing parts. She also teaches us that we waver, as subjects, in an ongoing field of object relations, between paranoid and reparative positions precisely because phantasy and fact have the similar material hold on our psyches. Moreover, we offer the reparative mode only after we endure paranoia, shed the pretense of mastery, and let go of the ideal, partial object to be able to bring the whole, complex object into our purview. Only then can we offer reparations — small offerings that seek to compensate for our violence, whether played out in our minds or more explicitly.

My brief turn to psychoanalysis offers recourse to another language so that what feels singularly complicated may become diffuse and varied within a larger psychic terrain. Mendieta's work points us toward our own death and our own violence, demanding that we pause and consider what it takes to be a person with gravity and lightness. Between strictly delineated markings of here and there, or then and now, we find quiet lines of flight as movement, slurries of small bits of matter.

I have always thought of Mendieta's Untitled: Body Tracks, 1974 as forming the downward, recalcitrant movements of diaspora. Her fingerprints and digits blend as she lowers herself toward the earth, and what we're left with is an early silueta, her most basic stroke, the slimmest signature of her work. She repeated these strokes throughout her career, lines that gesture, but don't suture or tidy. They draw nearer as she descends to her feet, pulled to the gravitational core of the earth, narrowing the gap without creating a meeting point. Mendieta's traces leave us with fragile topographic maps that journey into the quagmire of difficult object relations. As we look for them, they compel us longingly toward that which we can never fully grasp.

© 2019 The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Christina A. León is Assistant Professor of English at Princeton University. She is currently at work on her first book, entitled Radiant Opacity: Aesthetic, Ethical, and Material Relations in Latinidad. She has published a forthcoming work in Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, Sargasso: a Journal of Caribbean Language, Literature & Culture, Small Axe, and ASAP/Journal, as well as translations in the forthcoming Havana Reader (Duke University Press).

References

- While many thought the sculptures had faded or been mined for limestone, there have been quiet visits to the caves. The filmmakers of the first major documentary on Ana Mendieta, Ana Mendieta: Fuego de tierra (1987) visited the site of Jaruco, as well as Galeria DUPP in 1997 and Olga Viso in 2002. Canadian artist, Elise Rasmussen, exhibited her own photos of the weathered cave carvings in a show called Finding Ana from her visit in 2012. More recently, Raquel Mendieta, Ana Mendieta's niece and goddaughter, has located both caves and is creating a film documenting these findings entitled Whispering Caves.[⤒]

- In Touching Feeling, Sedgwick invokes beside as the most privileged preposition in her book. Beside, for Sedgwick, invokes spatiality and proximity without teleology. She writes, "Beside permits a spacious agnosticism about several of the linear logics that enforce dualistic thinking: noncontradiction or the law of the excluded middle, cause versus effect, subject versus object. Its interest does not, however, depend on a fantasy of metonymically egalitarian or even pacific relations, as any child knows who's shared a bed with siblings." Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 8.[⤒]

- Here, I am inspired by the work of thinkers of spatial or proximate relations that need not be determinate or teleological: Sianne Ngai on interest as an aesthetic category of seriality, Sara Ahmed and Roy Pérez on queer and racial proximity, and Leon Hilton on the wandering lines of Fernand Deligny. See Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006); Leon Hilton, "Mapping the Wander Lines: The Quiet Revelations of Fernand Deligny," Los Angeles Review of Books, July 2, 2015; Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012); Roy Pérez, "The Glory that was Wong: El "Chino Malo" Approximates Nuyorico," Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory 25, no. 3 (April 2016): 277-297.[⤒]

- José Quiroga's elegant reprise of his journey to look for Mendieta's sculptures is documented in his chapter of Cuban Palimpsests, entitled "Still Searching for Ana Mendieta." While Quiroga was unable to locate the sculptures, his missed encounter becomes a poetic reflection on the very ethos of search without end. José Esteban Muñoz writes about Mendieta's legacy as an intensely brown vitalism and "afterburn." See José Quiroga, "Still Searching for Ana Mendieta," in Cuban Palimpsests (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005); José Esteban Muñoz, "Vitalism's after-burn: The sense of Ana Mendieta," Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory 21, no. 2 (December 2011): 191-198.[⤒]

- See Leticia Alvarado, "'What Comes after Loss?': Ana Mendieta after José," Small Axe 19, no. 2 (July 2015): 104-110; Joshua Javier Guzmán, "Notes on the Comedown," Social Text 32, no. 4 (December 2014): 59-68.[⤒]

- This question echoes the title of Leticia Alvarado's essay noted in the above footnote.[⤒]