1990 at 30

1.

The exercise that is "1990 at 30" raises a question about historical temporality: what is and isn't the theoretical tradition of the contemporary? Does 1990 mark the beginning of our "globalized" present — a "contemporary epoch [that] is historically unique"1 —or has it been supplanted in the historiographic sweepstakes to date and theorize the present by, say, 9/11, the 2008 financial crisis, the 2016 election of Donald Trump, or by analytic categories that have arisen more recently that take longer (and sometimes much longer) historical views, such as neoliberalism and the Anthropocene?

My uncertainty was exacerbated by the text that I was assigned by the editors, Arjun Appadurai's "Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy," and by the subject of the essay: globalization. At first glance, globalization is a topic entirely of our moment. We live in a globalized world; I teach global literature; Trump's trade policies are not anti-globalization but rather the enforcement of globalization on his own terms. And yet, despite the ambient ubiquity of globalization, the idea itself has the feeling of being slightly, almost uncannily, retro.

When I dusted off my copy of Appadurai's Modernity at Large (full of faded post-it notes from my graduate exams) and downloaded both versions of "Disjuncture and Difference," including the 400-page issue of Theory, Culture, and Society in which it appeared, I was transported back into the heyday of globalization theory. It was a weird trip. These were days when the word globalization seemed to hail scholars like a frontier goldrush. In works like Robert Reich's The Work of Nations (1991), Emmanuel Wallerstein's Geoculture and Geopolitics (1991), Kenishi Ohmae's The Borderless World (1990), and Anthony Giddens's The Consequences of Modernity (1990), one witnessed a rhetorical stampede, as scholars rushed to give ideological and discursive shape to an "epochal transformation." For a time at least, espousing that a "borderless world" was emergent and the "retreat of the state" imminent was a nearly uncontestable position. As Appadurai put it in "Disjuncture and Difference,"globalization called out for some kind of "elementary framework." This much seemed clear. The question was whose framework would stick. The crowd of contenders was thick. Despite their differences, though, few social theorists would have disagreed with Mike Featherstone (editor of Theory, Culture, and Society, where Appadurai's essay first appeared) when he claimed in 1990 that the task of social theory going forward would be to "both theorize and work out modes of systematic investigation which can clarify these global processes that render problematic the idea of society as it was understood to operate within the bounded nation state."2

Thirty years on, however, the humanities have moved on from the deeply felt imperative to theorize globalization. Browsing the list of panels at MLA 2020 in Seattle, the virtual absence of the term globalization was striking: out of roughly 600 panels, only 4 of their titles included the word. To be sure, in 2020 "globalization" is traveling under different names. These names include, among others, neoliberalism and the Anthropocene. Neoliberalism seems often to be taken as isomorphic with globalization, or as a more precise name for the political and economic operations therein. In turn, the Anthropocene and its cognates such as the planetary are imagined to subsume globalization, giving us a systematic picture of earth systems that posits relations not only between distant geographic locations but between the deep past and unstable present, and into the physical core of the planet itself. From the perspective of 2020, then, exactly what endures of the globalization theory of 1990 is uncertain. It seems either squeezed between or swept aside by the new meta-totalities of the moment.

2.

Reassessing "Disjuncture and Difference" means entering into, or opening up, a conversation about what remains important about the globalization theory of the early 1990s. Some of this output, especially of the triumphalist mode of Francis Fukuyama or Thomas Friedman, has been extensively pilloried, but these are extreme cases. Surely, the keywords that grew out of globalization theory — transnational, global, planetary, neoliberal — carry with them some of the ideas of the 1990 goldrush. Is there still a place for comprehensive theoretical models of globalization? And if so: which ones?

Appadurai saw the rush to define globalization as a political battlefield. The terms of that battle ran two ways, one less remembered than the other. On the one hand there was a conflict between Left and Center over friction and agency, order and disjuncture, openness and inevitability. For the Thomas Friedmans and Anthony Giddens of the world, there was something "inexorable" about globalization that had to be accepted because only it could "order the chaos."3 Appadurai disagreed. Theories of globalization worth their salt, he wrote in "Disjuncture and Difference," would be behooved with taking on "disorganized capitalism," and providing a portable social theory that neither dumbed it down nor capitulated to its dominium.4 It was imperative that the Left develop transferable schemata for visualizing and navigating globalization in all its disjunctive disorder and asymmetry, because if it didn't, it would cede power to create narratives of globalization to partisans of a liberal world order. This is a familiar story.

On the other hand, Appadurai faces another looming concern. He fears that theories and narratives about globalization would be left to theorists of Western-dominated epistemologies: Marxism, postmodernism, and poststructuralism. "Disjuncture and Difference," he hopes, can mark the beginning of a "restructuring of the Marxist narrative [of globalization] (by stressing lags and disjuncture) that many Marxists might find abhorrent. Such a restructuring has to avoid the dangers of obliterating difference within the 'third world,' of eliding the social referent (as some French postmodernists seem inclined to do) and of retaining the narrative authority of the Marxist tradition, in favor of greater attention to global fragmentation, uncertainty and difference."5 Alongside the battle between Left and Center, then, was a battle within the Left, between dominant epistemologies of the Global North and still emergent and highly heuristic epistemologies of the Global South.

Although the fact is slightly muted in "Disjuncture and Difference" (it becomes more apparent in his edited volume Globalization), Appadurai saw the starting point for a comprehensive theory of globalization in the particularities, capacities, and subjunctive power of the imagination, and especially the imagination of "deterritorialized" actors around the world, who were in almost every example postcolonial peoples. Against a model of center and periphery, or of a homogenization of the rest by the West, Appadurai recursively loops back to the colliding imaginaries of individuals and groups originating and moving laterally within the Global South. Their way of seeing and affiliating are as foundational a feature of globalization as the workings of the World Bank; and their aspirations for the world to come as powerful as economic forecasting.

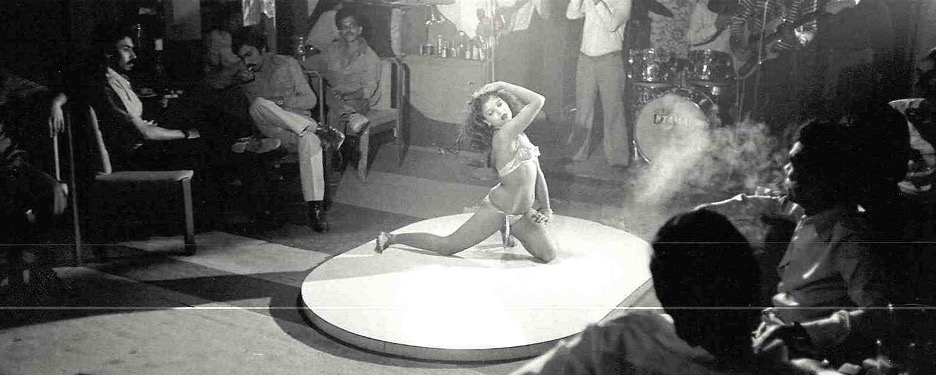

In perhaps the most salient example of what globalization looks like to Appadurai in "Disjuncture and Difference," he glosses Mira Nair's 1985 cine verité film, India Cabaret, in which we see multiple loops of this fractured deterritorialization as young women, barely competent in Bombay's metropolitan glitz, come to seek their fortunes as cabaret dancers and prostitutes in Bombay, entertaining men in clubs with dance formats derived wholly from the prurient dance sequences of Hindi films. These scenes in turn cater to ideas about Western and foreign women and their looseness, while they provide tawdry career alibis for these women. Some of these women come from Kerala, where cabaret clubs and the pornographic film industry have blossomed, partly in response to the purses and tastes of Keralites returned from the Middle East, where their diasporic lives away from women distort their very sense of what the relations between men and women might be. 6

Nair's film gives form to globalization as the cross-crossing trajectories and enmeshed desires in the heart of a Bombay cabaret. For Appadurai, though, the cabaret inflects all of the constitutive parts of an emergent world, possessed of the force to transform even the most foundational sets of relations: economic, sexual, geographic, and cultural. Many lines of sight, real and imagined, and the collision of competing expectations that threaten to leave nothing the same: this is Appadurai's globalization theory.

Years later, in a 2004 interview, Appadurai was asked to define the central elements of his theory of globalization. He turned to the leaders of the Bandung moment, whose meeting in 1955 gave inchoate shape to a postcolonial globalism that would seem, at first, entirely incongruous with the workings of a Bombay cabaret. "[T]he Bandung Conference of 1955 [forged] a kind of globalizing of the imagination . . . [P]eople like Nehru, Nasser, Sukarno, and Nkrumah, and so on, major leaders, their postcolonial aspirations and roadmaps for their own people were intimately tied up with their understandings of their place in the world, in history, in relation to each other."7 Beyond being fulsome scenes of postcolonial imagining and affiliation, what might the sordid encounters of India Cabaret and the strategic alliances of Bandung have as their common denominator? In Appadurai's view, each points to the becoming of a world after empire — difficult and unpredictable in both cases — where relations between people would neither "presume the uniform and general existence of the nation-state" nor ascribe to the partitions and ordering of European modernity. 8

Appadurai's work of the 1990s brings to light the unfinished business of globalization theory as a theory from the South — a theory that might have been too quickly overtaken by the terms and scales of analysis in which we now more commonly operate. True, the Jamesonian school of Marxism that Appadurai hoped to restructure — with its fidelity to a "singular modernity" and a model of core and periphery — no longer dominates our disciplines and their scalar imaginaries. But it, unlike "globalization theory" per se, has outlived the 1990s boom, especially amongst the Left. It motors on, for example, in the work of the Warwick Research Collective and Vivek Chibber and the Jacobin/Catalyst crowd of Marxist theory. At the same time, another important thinker with ties to the globalization theory of the early 1990s, David Harvey, later turned to the history and critique of neoliberalism, giving over little space for imaging alternatives outside of a classical Marxist restructuring of the global economy.

Meanwhile, Appadurai's ally in challenging Marxist universalism, Dipesh Chakrabarty, has embraced a geological timescale that threatens to make obsolete the methods and aspirations of postcolonial worldmaking. The Anthropocene, he writes in an oft-quoted article, challenges the "analytic strategies that postcolonial and postimperial historians have deployed in the last two decades."9 Chakrabarty's citational dominance over the last decade in relation to Appadurai, especially in literary studies, confirms this fact. Moreover, when Chakrabarty's embrace of the Anthropocene is critiqued, it is often done so from a Marxist perspective.10 Yet few scholars in the humanities, to my knowledge at least, critique the Anthropocene in the name of a renewed attention to the unfinished debates on globalization, even as work on the Anthropocene tends to do precisely what Appadurai worries about with regards to some Leftist theories of globalization: "eliding the social referent."

In the early 1990s, globalization was the keyword for describing the world's evolving and ultimately irreversible connectivity, for better or worse. With the unraveling not so much of the term itself but the multiple narratives and visions of global society that emerged from the debates around the term, we risk losing intellectual threads that can still be woven into contemporary movements for global democracy. If nothing else, Appadurai's vision of globalization as a theory of and from the South is a salutary alternative to today's false dichotomy between global capitalism and economic and cultural nationalism. For Appadurai, globalization theory, at its best, would help give shape and meaning not only to a world beyond the nation state but also, just as importantly, a world after empire. Thirty years on, it's worth considering what we've gained and what we've lost in the unfinished project to narrate and describe such a world. Have we done our best to venture down the pathways traced by "postcolonial aspirations and roadmaps," as Appadurai puts it, or have we too hastily thrown those roadmaps out, and drawn up new ones?

Hadji Bakara is an assistant professor of English and human rights at the University of Michigan. He is completing his first book, Governments of the Tongue: A Literary History of Human Rights, and is at work on Refugee Futures: A Political Theory of Time.

References

- David Held, David Goldblatt, Anthony C. Mcgrew, and Jonathan Perraton, Global Transformations: Politics, Economics, and Culture (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1999), 340.[⤒]

- Mike Featherstone, "Global Culture: An Introduction," Theory, Culture, and Society 7 (1990): 2.[⤒]

- Thomas Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree: Understanding Globalization (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1999), 24.[⤒]

- Arjun Appadurai, "Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy," Theory, Culture, and Society 7 (1990): 296.[⤒]

- Ibid., 310.[⤒]

- Ibid., 303.[⤒]

- John C. Hawley, An Interview with Arjun Appadurai, in Revathi Krishnaswamy and John C. Hawley eds. The Postcolonial and the Global (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 298.[⤒]

- Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 23.[⤒]

- Dipesh Chakrabarty, "The Climate of History: Four Theses." Critical Inquiry 35 (2009): 198.[⤒]

- See, for instance, Sandeep Banerjee, "Beyond the Intimations of Mortality: Chakrabarty, Anthropocene, and the Politics of the (Im) Possible." Mediations 30, no. 2 (2017): 1-14.[⤒]