The 7 Neoliberal Arts

Spike Lee: Rob, have you had any formal art training?

Rob Liefeld: No, just a lot of imagination.

— Levi's 501 Button Fly Commercial (1991)

I.

In the second episode of The Comic Book Greats, a direct-to-video program released in 1991, fans were given a rare opportunity to witness the birth of a superhero. The episode featured Rob Liefeld, artist and writer of Marvel's X-Force, in an interview with Stan Lee. Liefeld was only twenty-four but had already become one of Marvel's most popular artists. After a successful run on New Mutants, his X-Force #1 had sold over 5 million copies across multiple printings, and he had just appeared in a commercial, directed by Spike Lee, for Levi's 501 Button Fly jeans.

Nervously gripping his pencil, avoiding eye contact, Liefeld explained to Stan Lee that the key to his popularity was his "personal vision."1 Hoping perhaps to witness some of this vision in motion, Lee brought the young cartoonist to a drawing table and asked him to invent a new character on the spot.

Liefeld drew a character called Diehard, but when Lee complained that Diehard's costume didn't feature enough accessories, the artist created a second character called Cross (tagline: "He's the guy you don't wanna cross"). The character donned giant shoulder pads, wore a massive over-stuffed utility belt, and carried an improbably large gun.

"Everyone's going to have a Cross comic book," Liefeld predicted, "cause he's cool and he's accessorized."

"Have you ever drawn him before, or are you making him up now?" Lee asked.

Liefeld replied, "This is the world premiere."

"So I've been at the beginning of a new superhero," Lee marveled. As Liefeld continued drawing, Lee added, "And obviously if our lawyers are tuning in, you and I are creating this together so we both share the copyright."

After a beat, Liefeld said, "Have your lawyer call mine."

II.

Liefeld was, of course, lying.

The character Cross had already appeared in Comic Buyer's Guide a few months earlier in a black-and-white advertisement for a new series Liefeld was planning to publish with Malibu Comics. The series, The Executioners, was a superhero book about "Rebel Mutants from the future come to destroy their past."2 Cross was the leader of the rebel mutant team, looking very much like a younger version of Cable, a character Liefeld had created for Marvel's New Mutants. Cross's teammates resembled other Marvel properties, leading Liefeld's editor at Marvel, Bob Harras, to call him at six-thirty in the morning and threaten him with legal action if he went forward with the book.3

Liefeld scrapped The Executioners, but he was ready to leave Marvel. By the time he appeared on camera with Stan Lee, Liefeld and other prominent Marvel artists were already discussing the possibility of forming their own company, Image Comics, which would be a jointly owned imprint that would allow each artist to run his own studio, own his own intellectual property, and keep profits their creator-owned characters generated. Liefeld and six other Marvel pencillers (Todd McFarlane, Jim Lee, Marc Silvestri, Erik Larsen, Jim Valentino, and Whilce Portacio) would officially announce the launch of Image Comics in February 1992.

The on-camera push and pull between Stan Lee and Liefeld, Lee's instant move from marveling at the creation of a new superhero to wrestling over ownership, registers the balance of power between art and commerce in comics circa 1992. Liefeld and his fellow Image founders were celebrities, each bearing an inalienable relationship to a namable and highly lucrative drawing style that, they hoped, would transcend the particular titles or characters they worked on. Yes, they could command six-figure or even seven-figure salaries from Marvel, but they wanted more. They wanted to own their characters, produce their own books, and control their economic futures, and they hoped they might bring their fans with them.

This was the moment, after all, when a discourse of creator's rights circulated in the comics world. It was widely understood that cartoonists such as Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, who created Superman, or Jack Kirby, who helped create many Marvel characters, had been badly treated. The failure to compensate these cartoonists for their wildly popular characters was considered a scandal. The 1970s saw many battles between cartoonists and the corporate publishers who typically paid them on a work-for-hire basis. Artists fought for standardized rates. They fought to have their artwork (which could be sold to collectors) returned to them. Some tried to unionize. When the direct market of comics specialty stores became the dominant form of comics retail in the 1980s, a few artists pursued self-publication with major distributors and even direct sales.

In 1988, artists associated with the independent cartoonist David Sim endorsed a so-called "Creator's Bill of Rights," which, to be sure, didn't directly influence the founders of Image but gives a flavor of the spirit of discussions happening at that time. One signatory, Steve Bissette, suggested that "[o]ne of the hardest things to sink into the heads of artists...is that there's not a division between businessmen and artists.... [T]he first lesson is you've got to be a businessman and an artist. If you're going to make enough of a living to survive and be drawing comics three years from now, you have to have some business savvy."4

This was also a moment of rampant speculation. Collectors and fans were hungry for new series, new characters, new #1 issues, and myriad variant covers; they bought comics they thought might become valuable by the boxload. Marvel and DC were more than happy to give speculators what they wanted, creating new series, producing variant covers featuring all manner of gimmick, engineering improbable crossovers. Artists like Liefeld and his Image co-founders were very much part of the speculative machinery. Celebrity drove sales. Todd McFarlane's Spider Man #1, for example, sold over 2 million copies, Jim Lee's X-Men #1, 8 million.

In 1993, the bubble would pop, laying waste to the nationwide network of comic-book specialty shops that had emerged in the 1980s; nine out of ten would close. But at the height of the frenzy, when the boom market propped up many improbable ventures, starting an independent studio could seem like more than a way to make money. Owning your own intellectual property, being a creator-owner, was also a way of demonstrating that artists were central to the success of Marvel and DC — no artists, no characters; no characters, no profit.

Being an entrepreneur and being an artist weren't separate activities, or even activities instrumentally associated with one another. Rather, at this moment, to be an autonomous artist could seem to mean being economically autonomous, owning your own business, being the sole or at least primary proprietor of your named style, that is to say, your personal brand.

III.

What might it mean to take Liefeld's personal vision seriously?

To ask such a question may seem bananas. To have an inalienable relationship to a lucrative style does not mean that that style is good. As Bart Beaty and Benjamin Woo note in The Greatest Comic Book of All Time, Liefeld is perhaps the least plausible contender for the title of "greatest" anything. Indeed, Liefeld is — I am duty-bound to mention — arguably one of the worst cartoonists of all time. His figures undermine any canon of human anatomy. His men are built like roided bodybuilders, his women heavily augmented pornographic actresses.

These characters invariably scowl with rage and are accessorized with the same generic pouches, guns, utility belts, and helmets. They appear on pages devoid of any sense of composition, in layouts impatient to move from one overstuffed splash page to another, each featuring some hulking body punching, stabbing, or shooting another body, often floating in a space with no discernable background. Liefeld is "an exemplar of the worst excesses of the nineties, from paper-thin characterization to wildly exaggerated anatomies," Marc Singer notes.5 His myriad sins have been well-documented.6

Beaty and Woo's explication of Liefeld's style is openly cheeky. Liefeld is, after all, an artist who cited "toy tie-in comics like GI Joe, Micronauts, and Rom as formative influences."7 What Beaty and Woo don't do is actually analyze Liefeld's art in detail. To do so would be beside the point, an application of analytical methods to material unable to bear such scrutiny. What remains is a cultural studies analysis of the social significance of Liefeld's style.

The word most often used to describe this style, and the style of Image more generally, is "excess." Beaty and Woo suggest that Liefeld's hard bodies exemplify a poetics of excess, a "reductio ad absurdum of a dynamic visual style."8 Anna F. Peppard, in the best scholarly analysis of Liefeld, likewise speaks of the artist's "love of excess."9 Discussing the Marvel-era styles of Liefeld, McFarlane, and Jim Lee, Peppard explores precisely "what is being rendered excessive [by Liefeld and his fellow cartoonists], why this excess is considered necessary, and what [this excess] is trying to achieve."10 Liefeld's bodies showcase a "newly unstable conception of masculinity," one she associates with steroid-fueled "mass monster" bodybuilders such as Markus Rühl,11 whose carefully crafted bodies Adam Locks refers to as "Post Classical."12 The exaggerated gender norms of Liefeld's figures are a visual "reaction to feminist gains."13 Liefeld's superheroes are, Peppard ultimately suggests, similarly Post Classical.

Peppard's reading is persuasive, but what we should not assume, as other critics do, is that Liefeld and Image more broadly embody a postmodern aesthetic. Surely, the fact that the founders of Image voluntarily adopted the name Image tempts us to undertake such a reading. Beaty and Woo claim that Liefeld's typical figure, borrowing language from Jean Baudrillard, is "a simulacrum: a hyperreal caricature of a cartoon."14 Another critic suggests that "Image [Comics]'s very name suggests the extremes that their stylized portrayals of masculinity have taken as pure form, as pure image."15

But pure form and pure image are not the same.

Pure image suggests a kind of popular postmodernism, a time of "emphatic surfaces and lost historicities," a doubling down on the MTV tactics that stereotypically defined the period; these are heroes who "are nothing more or less than what they look like."16

Pure form, meanwhile, is a phrase one might expect to find in an essay by Theodor Adorno or Clement Greenberg or Michael Fried. The pursuit of such pure form — or, what amounts to the same thing, the pursuit of form at all — would be synonymous with the pursuit of art as "self-legislating artifacts."17 That is to say, the pursuit of autonomy.

What would it mean to imagine that we might undertake a close reading of Liefeld's style? Isn't Liefeld's brand of excess merely a banal example of capitalist overproduction in the realm of comics? Or is there some sense in which Liefeld's aesthetic autonomy can be said, without contradiction, to be a function of his pursuit of economic independence?

IV.

Take Liefeld's first creator-owned series for Image Comics, Youngblood.

A self-identified part of the "MTV generation," Liefeld hoped to create MTV superheroes.18 "It's got a lot of government corruption and genetic corruption," he explained in an interview with Wizard magazine. "In their environment, Youngblood are the super celebrities." They are "the biggest stars around." His heroes "have P.R. people for when it's all done. They have a guy who spreads their speech for them. They have costume designers. They think about their public image." Liefeld's representation of superfame, clearly a mediated reflection on his own sudden celebrity, comes accompanied with a ready-made media critique.

"In the very first issue," he promises, "we see how the media can be used to control the way we think. It's a lot about media manipulation and the superheroes are the vehicle to tell the story. There's a lot of characterization and insight to their private lives, but that's the basic thrust."19

This is not necessarily a bad idea for a book and, done well, some version of Youngblood might have joined the ranks of other self-conscious superhero narratives of the 1980s by Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Warren Ellis, and Frank Miller. Unfortunately, to say Youngblood #1 fails to live up to Liefeld's avowed ambition would be a grievous understatement. It is a travesty of bad art and bad dialogue (written by Hank Kanalz to accompany the incoherent story by Liefeld). A reviewer for The Comics Journal labelled it "the worst comic book I have ever read," and noted that its characters resemble "near-sighted steroid abusers suffering from constant intestinal distress."20

Even Liefeld recognized the flaws in this hastily assembled first issue; he had the book's dialogue rewritten and the story "remastered" into a slightly more coherent form for a hardcover collection of Youngblood. But the original is — not despite but because of its uncompromising badness — perhaps the more significant work.

Louise Simonson, who worked with Liefeld at Marvel, once remarked, "It took me about six months to figure out that Rob really wasn't interested in the stories at all. He just wanted to do what he wanted to do, which was cool drawings of people posing in their costumes that would sell for lots of money."21

This description suggests that Liefeld's primary motivation was to make as much money as possible. But, I would argue, Youngblood #1 represents a liberation from concerns of marketability. Liefeld would never again enjoy as much creative freedom as he did with this issue. He would never again pursue the logic of his "personal vision" with such rigor.

V.

Youngblood #1 introduces readers to two separate stories featuring two genetically enhanced superhero teams (one domestic, the other international) that work for the US government. The two stories are bound together with tête-bêche binding, one side featuring the Home Team, the other the Away Team, which gives Liefeld an opportunity to produce two covers for his inaugural issue. There is otherwise very little editorial apparatus. Each story includes a page with a team photo, which labels the members of each team before launching into their narratives. The stories meet in the middle, which features an invitation for the reader to join the Rob Liefeld Fan Club ($4.50 for an annual membership).

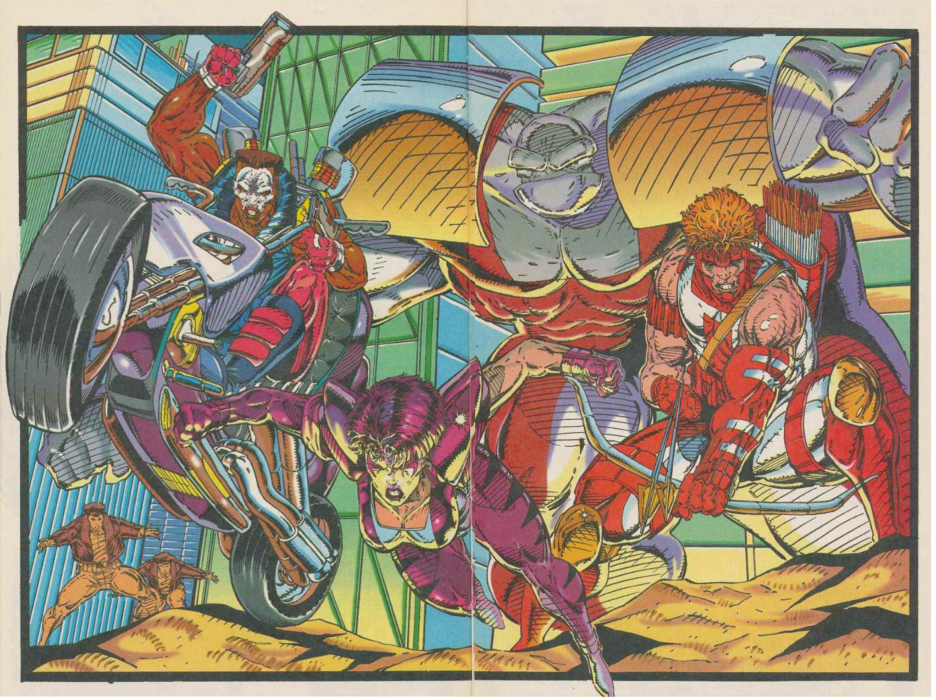

Whichever story you choose, you will have a similar reading experience: anonymous bodies in violent motion, indistinct super-powered individuals beating up other indistinct super-powered individuals, and then the story halts.

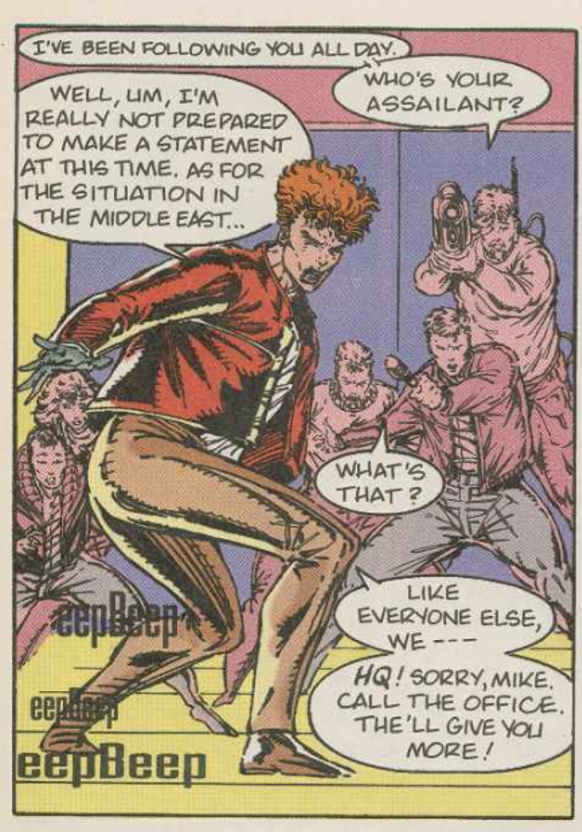

The Home Team story begins with Home Team leader, ex-FBI agent Shaft, shopping at a mall with his assistant D.A. girlfriend. After a confusing sequence, where Shaft pursues an apparent shoplifter ("'Tis the season for giving, not stealing!" our hero shouts), an assassin attacks the ex-FBI agent.22 Shaft — whom, we're informed, typically fights with a bow and arrows — is forced here to defend himself with . . . a pen (Figure 1).

Whooosh.

After killing his assailant, Shaft quips that he's glad the pen is "good for more than signing autographs."23 He glowers over the body of the would-be assassin, dead in a mall fountain, and observes, "No I.D. No pulse. No answers. Damn it!" 24

Members of the press suddenly appear!

The camera and microphones they carry are visually redolent of the silver sniper rifle the assassin used a page earlier. The dynamic action pose of the fleeing celebrity is, articulated by Liefeld's jagged line, virtually indistinguishable from the figure of the superhero in combat. This equivalence might be taken as evidence of Liefeld's limited talent; the artist is as bad at drawing everyday objects (cameras, microphones) as he is at drawing human feet. But the equivalence might also be taken as an expression of Liefeld's personal vision.

Youngblood is set in a world of nonstop motion, where the laws of perspective or gravity do not obtain, where the apparatuses of media production — a pen, a camera, a microphone — are (in many cases literally) weaponized, and where bloodless human violence is, on the contrary, little more than a means of aesthetic gratification. Every setting, every gesture, every instant is reactive, coiled with an explosive dynamism, threatening contextless destruction. Liefeld is after pure action, pure dynamism, stripped of subject matter. What these characters happen to be doing is less important than the zealous way in which they go about it.

Shaft is (suddenly!) called back to Youngblood headquarters, and the rest of the Home Team story is devoted to assembling the team in the most perfunctory way and setting them into combat against another team of generic villains called The Four (because there are four of them). The story ends mid-fight, Liefeld's heroes caught as if in amber in midair on a two-page spread, ever flying toward their opponents, hanging in space, endlessly in battle, with nary a "To Be Continued" to indicate that the story is concluding.

If, as Michael Clune has argued, some artists pursue a kind of art that fights against time, or rather, the tendency of "neurobiological time" to render aesthetic experience stale, Liefeld seems to want to find a visual form that makes the adolescent aesthetic of superviolence permanently dynamic.25 We might call this the superhero as still life — or perpetual motion machine. It does not matter which, since they amount to the same thing.

VI.

When we flip Youngblood #1 180 degrees, we read the story of the Away Team.

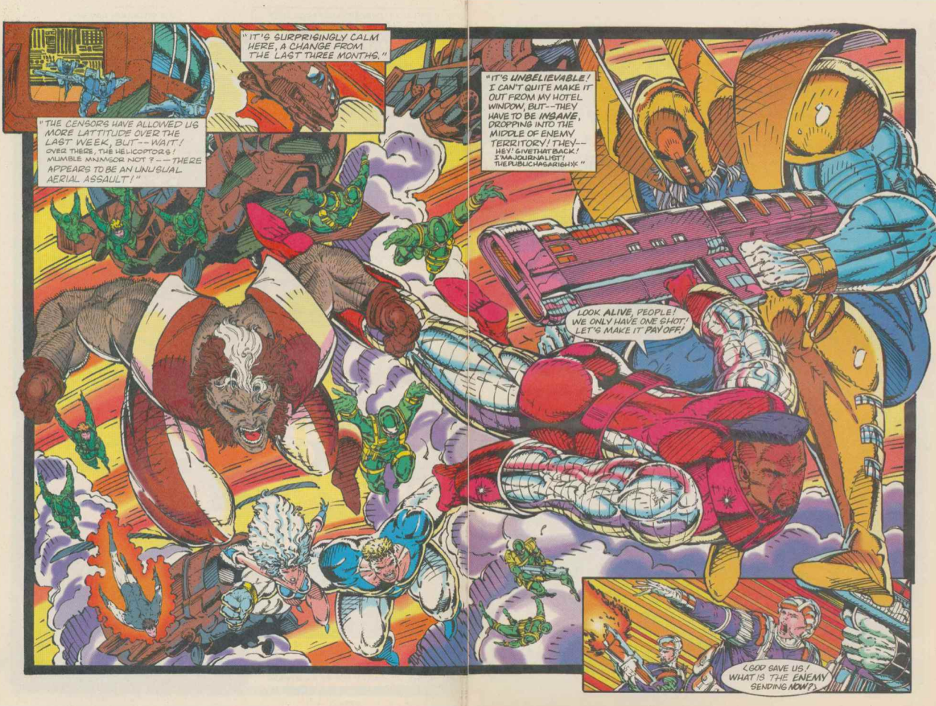

This story is slightly more coherent than the Home Team's story, if only because there is a beginning, middle, and end. The first page features a simple 2 x 3 array of panels shaped to look like television screens, which provide exposition about the geopolitical crisis that the Away Team is intervening in. The layout seems meant to recall the opening pages of Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns (1986), which also features arrays of television-screen panels.

On the next two-page splash, the Away Team leaps from a helicopter into combat, to face the minions of a villain, based on Saddam Hussein, named Hassan Kussein.

These characters are, again, generic, personalities and powers indistinct. They change size from panel to panel. Their bodies float in space, or rather in a sort of non-space, free from constraints; it is not so much that these bodies are flying as they are innocent of the truth of gravity. Each face is scrunched into a visceral snarl. Each body is highly articulated, each muscle gleaming, perhaps bearing a backstory of its own.

The Away Team plot, such as it is, is completed without much in the way of obstacle or interruption. A character named Psi-Fire uses his telekinetic power to murder Kussein, and the media cover up the murder by claiming that Kussein committed suicide. The interpretation we offered of the Home Team story might be repeated here. But I want to draw attention to a different feature of this half of the book.

When Psi-Fire finds Kussein, they have a brief conversation. "I actually admire what you've done here in this backwards country," Psi-Fire explains to the groveling Kussein.26

Kussein tries to bribe Psi-Fire, but Psi-Fire cannot be bought.

"I enjoy this part of the job!" he explains to Kussein. "It can be a headache sometimes...but I have high job satisfaction. This kind of stuff I'll do for free..."27 he says while telekinetically causing Kussein's head to explode.

We are meant to understand, by the shocked reaction of his teammates, that Psi-Fire is a bit of a psychopath or loose cannon. "He did it again!" laments one teammate, Cougar.28 But the moment where his fellow Away Team heroes discover the murder is mostly played for laughs.

Kussein had it coming.

What we have here is not only a story of superbodies bashing superbodies. We have, too, a representation of high job satisfaction — of the sort of work one would do for free — that is also an example of that work, the work of the cartoonist as entrepreneur, which was the real object of the fantasy sold by Image Comics.

VII.

In 1992, I was thirteen years old and a big fan of comics — and a regular reader of Wizard magazine, which did more than any other publication to hype Image Comics.

Looking back, I will admit that I was a fan of the wrong comics — it might have been spiritually improving if I had picked up an issue or two of The Comics Journal — but at the time I was very confident in my critical judgments. I would have defended my aesthetic preferences vigorously, and probably would have had opinionated disagreements with every sentence in this essay.

When I started high school in the fall of that year, I joined the school's Cartoonists' Society, determined myself to become a cartoonist. I arrived onto an adolescent scene (mostly, but not exclusively male), consisting of teenage fans who (like me) intended to step onto the comics field as players.

I was introduced to Rob Liefeld at those afterschool meetings, in a context that framed him, from the outset, as a bad artist, bad at anatomy, bad at layouts, yes, inexplicably popular, but not an artistic model to be emulated. His avowed badness was contrasted with other Image artists such as Todd McFarlane and Jim Lee (whom everyone seemed to agree was the best of the best). Despite these critiques, you could not miss the admiration for what Liefeld had accomplished.

I report this history not to confess my sins — though writing these sentences feels a little like a confession — but to offer testimony that adolescent consumers of Image Comics knew exactly what they liked about these books.

What the adolescent male reader aspired to become when he read Youngblood #1 wasn't a muscle mass bodybuilder but rather the sort of artist whose job it was to control an empire of intellectual property consisting of such bodies. To be an artist was not just to be popular, but to own your popular creations, to run a studio that produced the books that feature those creations.

To become a creator-owner, from this historical vantage point, was to become a small-scale capitalist who owned his own intellectual property, jealously guarding it from those who might corrupt its purity. What I would suggest today, almost thirty years after I first joined the Cartoonists' Society, is that this aspiration is also normatively encoded on the pages of not only Youngblood #1 but many other books that Image Comics produced in the early 1990s.

(Do you have any formal art training, Rob?

No, just a lot of imagination!)

VIII.

Everything we might say about the early years of Image might seem, at one level, obvious. Their books licensed an adolescent fantasy of power. These fantasies made the corporate power of the superteam (most of Image's early books were team books) into figures for the corporate power of the independent creator-owned studio. Moreover, Liefeld and his compatriots might well be understood as engaging in the same kind of deconstruction of superhero narrative as Moore, Morrison, Ellis, and Miller. To be sure, they were generally worse artists and writers, but they clearly absorbed the lessons of the 1980s, and they wanted to create metafictional heroes, to imagine superheroes for an age of music videos, and thereby critically reflect on their own furious fame.

Such an allegorical reading might follow the protocols of the industrial formalism perfected by critics such as Jerome Christensen, J. D. Connor, and Michael Szalay.29 Christensen, for example, revises the "studio authorship thesis," suggesting that Hollywood studios might indeed fruitfully be understood as "authors" of their films if we understand the corporate studio as "a person who is not actual [that is, who is a legal person] but who nonetheless qualifies for the status of the intending author."30 Something similar might be said for Image's semi-autonomous studios. One might note that Spawn's deal with the devil resembles, to a degree, Todd McFarlane's claims about his unsatisfying deal with Marvel. Jim Lee's WildC.A.T.S. organizes its narrative around the sort of multinational corporation Lee himself (on the one hand) fled and (on the other) hoped to build anew.

These books, also, like Liefeld's art, were committed to a fantasy of perpetual dynamism, an endless excitement that mirrored the fantasy, characteristic of all economic bubbles, that the party will never end. Image's success rode a wave of growth fueled by speculators, who collected books for resale on the collector's market. Such speculation created the conditions of possibility that allowed these creators to fulfil their dreams with an unusual purity. So it might be true that the ideal book of the era was not even read, but it was arguably this lack of interest on the part of speculators in reading the books that they bought that makes it interesting for us, looking back, to do readings of them.

The market bust of 1993 shattered that early vision of Image. In time Liefeld (and fellow co-founder Jim Lee) would leave the company. (Liefeld would, through a complicated set of circumstances, lose his rights to Youngblood.) Robert Kirkman (creator of The Walking Dead) and Eric Stephenson would define the new ethos of the company, embracing Indie creators and a wider diversity of titles. Tellingly, Stephenson has said that he has hoped to make Image into the "HBO of comics."31 Whatever else we might say about it, the new Image is publishing far better books today than it was in the early 1990s.

This transition to what we might call the era of Quality Comics has not, I would argue, been as much of a transition as it appears but is rather continuous with the original Image project. One can see in the bad anatomy of Liefeld a figure of the dream of creative autonomy. But we see, too, that this autonomy is not defined against the market, or as freedom from the market. In a neoliberal era that has upheld the artist as the very figure of non-alienated work, it is the essence of the artist to own her intellectual property, to turn herself into a walking brand. The autonomy of her art is an expression of her independence as a producer. This is, to be sure, not a modernist understanding of autonomy, and we might safely assume that Walter Benjamin would not endorse this version of the "author as producer." But the convergence of art and commerce that Image Comics emblematizes was a distinct and durable historical junction. Untangling this junction might become a long-term research program for critics working in the emerging discipline of comics studies and for scholars more generally interested in contemporary art.

The story of Image is often contrasted with the story of more art-oriented producers such as Fantagraphics Books or Drawn & Quarterly. The style of Liefeld and his confederates could not seem more different from that of, say, Daniel Clowes or Adrian Tomine or the Hernandez brothers or artists associated with RAW or, really, anyone we might expect to see celebrated on the pages of The Comics Journal. But the truth of cultural history is that the two zones of the comics field — the open market and the restricted field — had far more in common than many might be inclined to admit. Any comics scholarship or cultural history that does not reckon with this similarity will fail to account for the logic that drives the neoliberal arts of the present.

Such is the lesson the career of Rob Liefeld teaches.

Lee Konstantinou is Associate Professor of English at the University of Maryland, College Park. He wrote the novel Pop Apocalypse and the literary history Cool Characters: Irony and American Fiction. He's working on a monograph The Last Samurai Reread and an edited collection Artful Breakdowns: The Comics of Art Spiegelman.

References

- Rob Liefeld Interview in The Comic Book Greats (Livonia, MI: Starbur Home Video, 1991).[⤒]

- Sean Howe, Marvel Comics: The Untold Story (New York: Harper Perennial, 2013), 330.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Gary Groth, "Interview with Steve Bissette and Scott McCloud," The Comics Journal, no. 137 (September 1990): 74 (my emphasis).[⤒]

- Marc Singer, Breaking the Frames: Populism and Prestige in Comics Studies (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2019), 242.[⤒]

- See Bill Hanstock, "The 40 Worst Rob Liefeld Drawings," Progressive Boink, April 21, 2012; Bill Hanstock, "40 MORE Of The Worst Rob Liefeld Drawings," Progressive Boink, June 14. [⤒]

- Bart Beaty and Benjamin Woo, The Greatest Comic Book of All Time: Symbolic Capital and the Field of American Comic Books (New York: Palgrave Pivot, 2016), 84.[⤒]

- Beaty and Woo, 79.[⤒]

- Anna F. Peppard, "The Power of the Marvel(Ous) Image: Reading Excess in the Styles of Todd McFarlane, Jim Lee, and Rob Liefeld," Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 10, no. 3 (2019): 2.[⤒]

- Peppard, 3.[⤒]

- Peppard, 10.[⤒]

- Adam Locks, "Flayed Animals in an Abattoir: The Bodybuilder as Body-Garde," in Critical Readings in Bodybuilding, edited by Adam Locks and Niall Richardson (New York: Routledge, 2012), 166-180.[⤒]

- Peppard, 6.[⤒]

- Beaty and Woo, The Greatest Comic Book of All Time, 80.[⤒]

- Jeffrey A. Brown, Black Superheroes, Milestone Comics, and Their Fans (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2000), 176.[⤒]

- Scott Bukatman, Matters of Gravity: Special Effects and Supermen in the 20th Century (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 55.[⤒]

- Nicholas Brown, Autonomy: The Social Ontology of Art under Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 28. [⤒]

- Patrick Daniel O'Neill, "No Holds Barred," Wizard: The Guide to Comics (June 1992) 13.[⤒]

- Ibid., 14.[⤒]

- Scott Nybakken, "Too Rare for My Taste," The Comics Journal (July 1992): 33.[⤒]

- Howe, Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, 321.[⤒]

- Rob Liefeld, Youngblood #1, "Home Team," 3.[⤒]

- Ibid., 4. [⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Michael W. Clune, Writing Against Time (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2013), 4.[⤒]

- Liefeld, Youngblood #1, "Away Team," 13.[⤒]

- Ibid., 14.[⤒]

- Ibid., 16.[⤒]

- Jerome Christensen, America's Corporate Art: The Studio Authorship of Hollywood Motion Pictures (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012). J. D. Connor, The Studios after the Studios: Neoclassical Hollywood, 1st ed. (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2015). Michael Szalay, "HBO's Flexible Gold," Representations 126, no. 1 (May 1, 2014): 112-34.[⤒]

- Christensen, America's Corporate Art, 13.[⤒]

- "The History of Image Comics (So Much Damage) | Part 5: Legacies and Impact," YouTube, November 20, 2017, (accessed August 25, 2020). Vertigo and AiT/Planet Lar have also both used the phrase the "HBO of Comics" to describe their aspirations.[⤒]