Mike Davis Forever

Angel's Flight, the 1901 funicular that still graces Bunker Hill, serves as a visual touchstone for a certain version of Los Angeles, one characterized by both noir aesthetics and working-class life. Because it was dismantled in 1969 and rebuilt half a block south of its original location in 1996 (in an event complete with an opening gala) it has a strong association in particular with the Los Angeles of the first half of the twentieth century, as represented widely in cinema. The Angel's Flight (registered trademark) "In the Movies" webpage lists a series of representations, primarily in noir and crime films and television shows; since the tram was reopened, it has been an emblem of nostalgia, featuring in The Muppets, La La Land, and the 2020 Perry Mason reboot.1

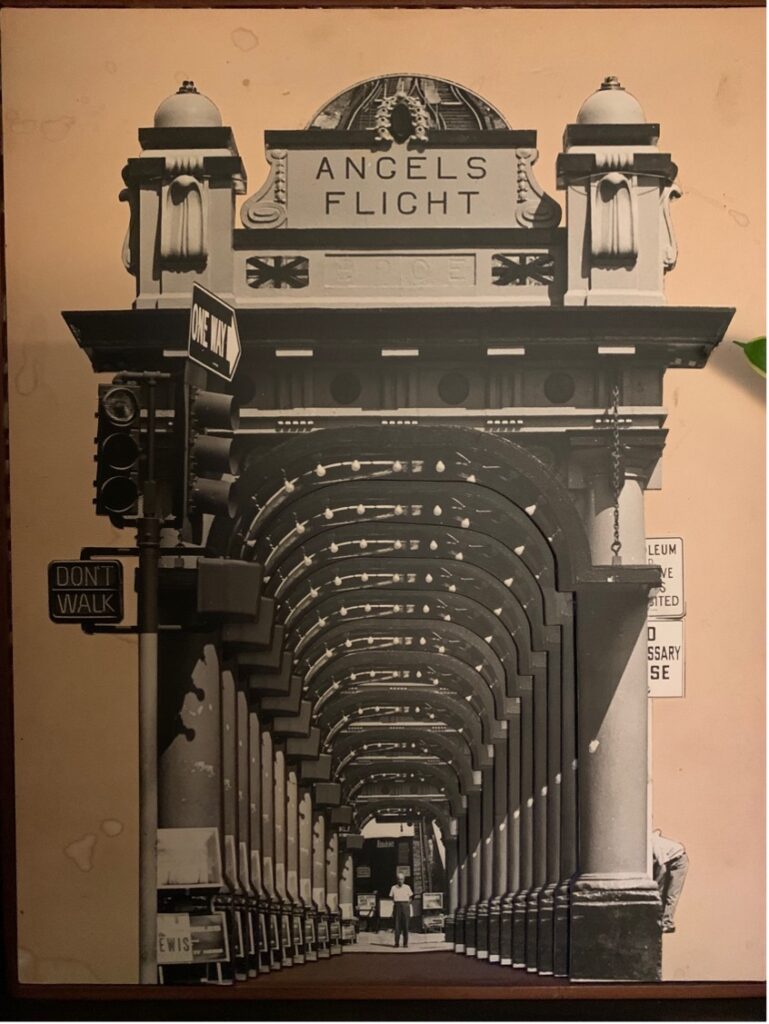

As a Los Angeles resident aware of the incline's impending destruction in the 1960s, my paternal grandfather created a three-dimensional photo collage of the Angel's Flight gate composed of a series of matted images glued together to imitate the path of the car.

It seems that from the 1950s, filmmakers, photographers, and artists were committed to representing Angel's Flight, anticipating the destruction that had been slated since 1952. The structure is depicted in The Glenn Miller Story (1954), Kiss Me Deadly (1955), and Indestructible Man (1955). But in this first life, and despite the anxiety that the tram might be doomed, the structure floats above Bunker Hill, betraying the struggles occurring in the neighborhood below. My grandfather's collage anticipates the nostalgia that would later characterize images of Angel's Flight: the depth that is represented by its three-dimensional construction follows the car's path down the hill without representing the neighborhood below. It sits at a representational tipping point: after the 1950s anxiety about the funicular's destruction represented in noir and crime cinema, the photographer/visual artist adopts the position of sentimental attachment.

In his essay "Bunker Hill: Hollywood's Dark Shadow," Mike Davis writes:

Once discovered by hardboiled writers and exiled Weimar auteurs, however, Bunker Hill began to exert an occult power of place. Here, overlooking L.A.'s monotonous, Midwestern flatness (Reyner Banham's "plains of Id"), was a hilltop slum whose decaying mansions and sinister rooming houses might have been envisioned by Edgar Allan Poe. Its residents, "women with the faces of stale beer . . . men with pulled-down hats" (Chandler).2

Davis proposes that Bunker Hill allows writers and filmmakers the chance to capture a vision of Los Angeles that accounts for its "slumminess" and puts its class inequalities at its center. In U.S. studies of urbanism and literature, scholars have often focused on New York and Chicago for a number of understandable reasons. But the seeming "newness" of Los Angeles, as well as other West Coast cities like Oakland and Seattle, has to some degree effaced the importance of literature and cinema that details the lives of the working class in ways that are attendant to the microevents of ordinary life. Literature and cinema of California more generally (I think of Carlos Bulosan's America is in the Heart, Charles Burnett's Killer of Sheep, or Boots Riley's Sorry to Bother You), shows versions of working that are only given their full due by Davis's conceptual frame. In Davis's writings, work as both a daily grind and the structuring concept of everyday life forms the undergirding for the development of L.A. as much as it does New York and Chicago. Because of this, his work provides an opportunity to reflect more carefully on cultural production that focuses on L.A., as much as the culture industry that makes its home in L.A.

In Kent MacKenzie's 1961 film The Exiles, the central location of Bunker Hill and the characters' movements through the city show how working, not working, and being "off" work suffuse every dynamic of daily life among these racialized characters. This is the primary methodological invocation that I share with Mike Davis, and it is an old-fashioned but trenchant one. While Davis's historical materialism turns to literary and filmic objects to track the imagined version of Los Angeles and its denizens and I focus on filmic and literary objects first, these are gestures that make Marxist methods central.

Among Mike Davis's many reflections on the cultural objects of Los Angeles is a chapter in Ecology of Fear about the emergence of L.A. disaster fiction. In this chapter, he works through the many ways that cultural objects seem to crave the end of L.A.: he details the various means that novelists and filmmakers have taken to show L.A. being invaded, blown up, bombed out, and abandoned. He notes, archly, that "if nuclear weapons have been detonated over the Hollywood sign an amazing 49 times, and City Hall has crumbled during the Big One, mother of all earthquakes, another 28 times, then sandstorms, comets, Japanese invaders, and Bermuda grass have all had their moments as well."3 But despite his focus on disaster in its highest-tension iterations, Davis's work in Ecology as well as City of Quartz has reconfigured the way that I've come to think about deep tension iterations in literature and cinema. By deep tension, and I position this in distinction from high tension, I refer to the technique in neorealist cinema that prioritizes small, ordinary moments that may appear to be external to "plot."

Working in an idiom of deep tension, and focusing on microevents and minutiae, recalls work by French Marxist everyday life theorists like Henri Lefebvre. Lefebvre's works on the city still have purchase because approaches to urbanism that center human labor and its effects, as he does, are important as mega-cities become increasingly unequal in the conditions of late capital — something that Davis also addresses in Planet of Slums. Furthermore, Lefebvre's engagements with Marx proper and his interlocutors illuminate Davis's own: Lefebvre and Davis both turn to Marx despite Marx having not engaged with urban geographies. Lefebvre writes in "Space and Mode of Production" that "even if he approaches Marx with a new synchronic, and not diachronic, way of reading, the reader of Marx will not find a systematic exposition of social space. The theme appears here and there, but it is not treated in detail. Why? Because capitalism (enterprises, networks of communications, and exchange) set itself up in natural space, the geographical space of first nature."4 Davis notes this too: in Old Gods, New Enigmas, he writes that Marx never wrote "a single word" about cities.5 But again, methodologically speaking, Davis's accounts of urban cultural objects require this kind of dialectical method.

In The Exiles, MacKenzie details the lives of a small number of American Indians in Los Angeles in the late 1950s; the film takes place over 12 hours. The script is based on interviews with a number of Native Bunker Hill residents; the primary "characters" are played by the interview subjects themselves. Couple Homer and Yvonne, who have relocated to Los Angeles from reservations, are each providing voiceover to a loose "plot" composed of Homer painting the town on a Friday night while Yvonne walks the neighborhood, reflecting on her current life and the expectations she has had of coupledom.6 In the first scenes, Homer and a number of his friends read comics and eat a meal in his and Yvonne's Bunker Hill apartment before drinking in a number of local bars. Homer spends the night playing cards in his friend Rico's apartment, meeting up with other Native men and women, and finally finds his way to an impromptu pow wow on "Hill X," a site overlooking the city that was filmed at Chávez Ravine, itself a highly contested area of Los Angeles.7 Yvonne goes to a movie, gazes into store windows, and eventually visits her friend Marilyn, staying the night with her. While the movie does not properly represent work, it represents a working-class population that is not always recognized as such. Relocation may have organized Native workers in a peculiar way, but it didn't invent the Native working class. The Exiles helps to show how Davis's many contributions to cultural history, particular the cultural genealogies of Los Angeles, provide sophisticated methods for how we read work in literature and cinema. In particular, Davis's archive demands that we turn to novels and films that feature deep tension and plotlessness at the expense of high tension and bombast.

In The Exiles, the audience does not see the characters working, but its entire logic is based around labor. Yvonne's voiceover details her struggle with the loneliness she suffers because of her carousing husband, whose friends have taken over their small apartment. She notes that, while Homer has a job (he is seen wearing white coveralls, which can be taken as a signifier for any number of industrial positions); many of his friends don't: "the rest of the guys, I don't think they really try to look for a job. I see them here almost every day. I wish that, at times, he'd stay home a lot. But he doesn't."

As Davis writes in the first chapter of City of Quartz, "if Los Angeles has become the archetypal site of massive and unprotesting subordination of industrialized intelligentsias to the programs of capital, it has also been fertile soil for some of the most acute critiques of the culture of late capitalism, and particularly, of the tendential degeneration of its middle strata." Here, Davis's focus is on noir, which focuses on "unmasking a 'bright, guilty place' (Orson Welles) called Los Angeles." He goes on to note that "Los Angeles in this instance is, of course, a stand-in for capitalism in general."8 In The Exiles, the pressures of post-war capitalism and the Indian relocation program (itself an outgrowth of the capitalist logic of turning "domestic dependents" into "laborers") show themselves through the neo-realist style and the attention to Native interiority. Its visual dynamics and emphasis on alienation open up the potential for reading it as a class critique.

In "Bunker Hill: Hollywood's Dark Shadow," Davis threads the methods of Marxist geography and history into his account of cinematic objects. Of Robert Siodmak's 1949 Criss Cross, he writes:

Siodmak . . . subsumed the city entirely into Bunker Hill and adjacent downtown streets. Apart from the opening aerial view of L.A. at night and the dénouement in a Palos Verdes beach house, Criss Cross is entirely located in Bunker Hill and its social space (Union Station and a Terminal Island factory count as the latter). . . . It is the first explicitly L.A. film, to my knowledge, that refuses any concession to canonical postcard landscape, except for the implacable, almost sinister sunshine that heightens the emotional tension. 9

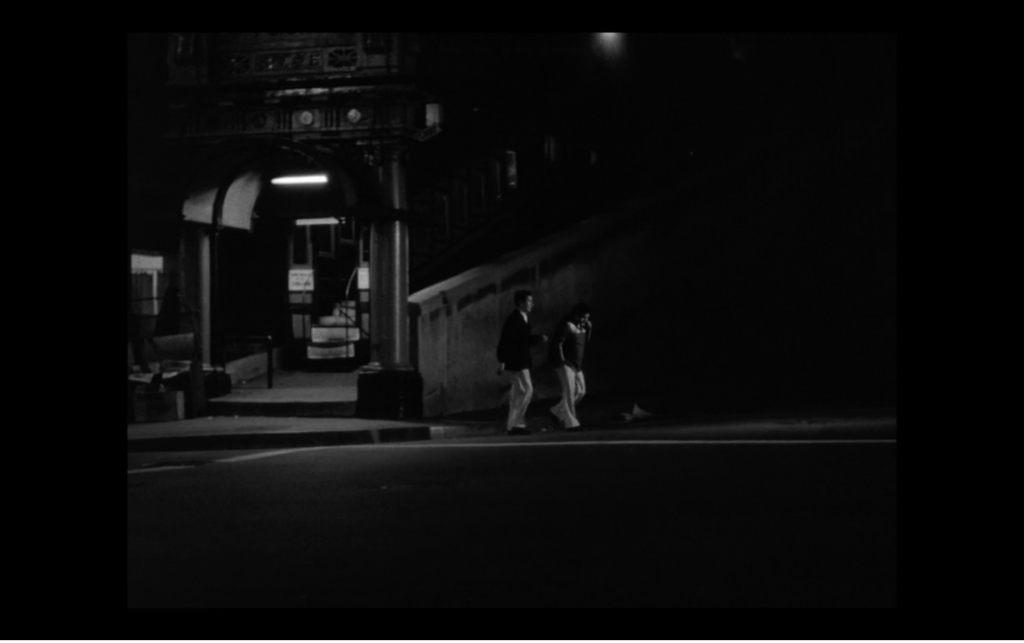

While The Exiles was filmed in 1958 and came out in 1961, MacKenzie's earlier "Bunker Hill 1956" shows how the anti-"postcard" aesthetics that had emerged in the 1940s accelerated after Bunker Hill was slated for destruction as of 1952. The Exiles's vision of Los Angeles avoids even "sinister" sunshine by being almost entirely photographed at night. And it is Angel's Flight, the iconic — and ironic — symbol of upward movement that grounds its narration.

The above image (fig. 3) appears early in the film: it stages the neighborhood and serves to establish location. But it also serves to establish the aesthetic program of the movie: the night photography makes the tram but particularly its track feel sinister when photographed from below. Angel's Flight also serves as an anchoring location: we see its gate when Homer moves from one bar to the next (fig. 4), and when Yvonne makes her way home from the movies (fig. 5).

The Exiles's focus on Bunker Hill, and Angel's Flight in particular, reorients us to visions of destruction that aren't imagined but intimately present — certainly, by the late 1950s when this movie was shot, all of the residents of Bunker Hill were conscious that the neighborhood was marked for erasure. As Davis writes:

A few years after the release of Kiss Me Deadly [1955], the wrecking balls and bulldozers began to systematically destroy the homes of 10,000 Bunker Hill residents. After a generation of corporate machination, including a successful 1953 campaign (directed by the Los Angeles Times) to prevent the construction of public housing on the Hill, there was finally a green light for urban renewal. A few Victorian landmarks, like Angel's Flight, were carted away as architectural nostalgia, but otherwise an extraordinary history was promptly razed to the dirt and the shell-shocked inhabitants, mostly old and indigent, pushed across the moat of the Harbor Freeway to die in the tenements of Crown Hill, Bunker Hill's threadbare twin sister.10

This is the Bunker Hill that The Exiles takes place in: precarious, seemingly isolated from the middle-class world, and overburdened with elders. With the populations of Bunker Hill keenly aware of their being primed for "relocation" (again), the tensions of the film and MacKenzie's earlier Bunker Hill 1956 show the importance of focusing on working class and poor people whose living spaces are on borrowed time.

In a contemporaneous review of The Exiles in Film Quarterly, critic Benjamin Jackson references the socialist aesthetics that characterize neorealist cinema, but also denies that The Exiles is in that aesthetic tradition. Jackson writes that, unlike the "Stalinist romantic radicalism of films like [Herbert J. Biberman's 1954] Salt of the Earth," The Exiles "leaves the most important things to the audience and in so doing it achieves its strength. It has none of the 'sell' which often contaminates the 'social documentary.' There are no plugs. No narrator harping behind the subject's back. It is just there; an entity in itself."11 Reading the film alongside Mike Davis, however, with his considerations of cultural objects and their reflection of class conditions, shows that even to be "just there" does not mean to be out of circuits of inequality. Whether there are "plugs" or not (and there aren't), the focus on Homer, Yvonne, and his group of friends shows that only a leftist critique in Davis's tradition, keenly attuned to the conditions of labor and its lived effects, can account for the importance of neorealist cinema.

The end of The Exiles focuses on the urban environment as much as the people who make it up. The final frames show the characters with their backs to the audience, walking into the distance.

But the movie cannot end easily: its second-to-last shot meditates on Yvonne's face; the film insists on retaining its commitment to recognizing her position.

Their partying over, and Saturday morning having arrived, the characters move away from the viewer and from the camera. Having illustrated the industrial urban landscape, and opened up the microevents of this working-class population, the film ends.

By 1949, writes Davis, Bunker Hill "was living on borrowed time. It not only picturesquely overlooked downtown but brusquely interrupted real-estate values between the new City Hall and the great department stores on Seventh Street. 'Bunker Hill,' argued a civic leader in 1929, 'has been a barrier to progress in the business district, preventing the natural expansion westward. If this Civic Center is to be a success, the removal or regrading of Bunker Hill is practically a necessity.'"12 Davis's work here and elsewhere reflects cannily on the mass expulsion of working people from urban centers, particularly in L.A., and The Exiles provides an example as well as an exemplar. For the Native population represented in the movie, relocation is a federal program but also a mode of city living: the American Indian as a subject in motion shows how urban precarity casts its shadow on an unexpected population of working people. From Davis's conceptions of Los Angeles, we have to see the Indian not as outlier or exception, but as exemplar for the logics of labor.

Megan Tusler is an Assistant Instructional Professor at the University of Chicago and Affiliate Faculty at the Affiliate Faculty at the Center for the Study of Race, Politics, and Culture. Her current monograph project, On Other Loathing, explores race, misanthropy, and negative affect in the ethnic American novel. She is a member of Faculty Forward/SEIU Local 73, the contingent faculty union at the University of Chicago, and co-host of the podcast "Better Read than Dead: Literature from a Left Perspective."

References

- "Angels Flight® in the Movies," Angels Flight® Railway, accessed July 20, 2022.[⤒]

- Mike Davis, "Bunker Hill: Hollywood's Dark Shadow," Cinema and the City: Film and Urban Societies in a Global Context, edited by Mark Shiel and Tony Fitzmaurice (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001), 33. The famous Chandler description of Bunker Hill quoted by Davis — "old town, lost town, shabby town, crook town" — is from The High Window (London: Penguin, [1943] 2011), 70.[⤒]

- Mike Davis, Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1998), 281.[⤒]

- Henri Lefebvre, "Space and Mode of Production," in State, Space World: Selected Essays, edited by Neil Brenner and Stuart Elden (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2009),211.[⤒]

- Mike Davis, Old Gods, New Enigmas: Marx's Lost Theory (London: Verso, 2018), 5. Italics in original.[⤒]

- For brief background, relocation, which is usually paired with "termination" in histories of American Indians of the 20th century, was a program developed by Dillon Myer in order to "relocate" Native people to cities like Los Angeles and provided short-term vocational training. PL 84-959, also called the Indian Adult Vocational Training Act, reads in part: "In order to help adult Indians who reside on or near Indian reservations to obtain reasonable and satisfactory employment, the Secretary of the Interior is authorized to undertake a program of vocational training that provides for vocational counseling or guidance, institutional training in any recognized vocation or trade, apprenticeship, and on the job training, for periods that do not exceed twenty-four months, and, for nurses' training, for periods that do not exceed thirty-six months, transportation to the place of training, and subsistence during the course of training. See 25 U.S.C. § 309, Code of Federal Regulations, title 25, chapter 1, subchapter D, part 26, "Job Placement and Training Program."[⤒]

- See Jordan Mechner's 2004 short film "Chávez Ravine: A Los Angeles Story" for a fuller account of the changes to Chávez Ravine between 1949 and 1960, when the land was eventually sold to L.A. Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley. Dodger Stadium remains at this location.[⤒]

- Mike Davis, City of Quartz (London: Verso, 1990), 18.[⤒]

- Davis, City of Quartz, 39.[⤒]

- Davis, "Bunker Hill: Hollywood's Dark Shadow," 43.[⤒]

- Benjamin Jackson, Review of The Exiles, "Special Issue on Hollywood," Film Quarterly 15, no. 3 (Spring 1962): 62.[⤒]

- Davis, "Bunker Hill: Hollywood's Dark Shadow," 38.[⤒]