Locating Lorine Niedecker

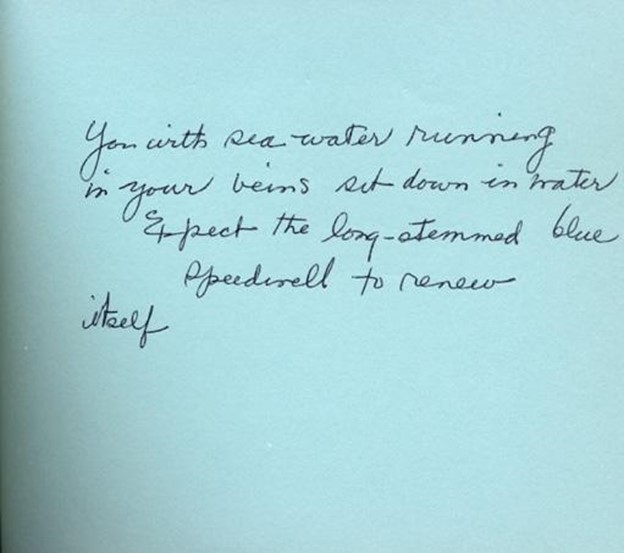

From the secret notes

I must tilt

upon pressure

execute and adjust1

One doesn't possess poetry or a poet. Poet's poet: does this mean a famous unknown celebrated by other relative unknowns? Niedecker's Collected Works was, for me anyway, an expensive book in hardback circa 2002, one likely bought on a credit card. I've taught with it many times, leading poets through its pages from first to last, reading and writing poems, thinking and conspiring alongside. What is my relationship to this lesser-noticed genius of weeds and water? To being a poet and being under-employed and in a body gendered as a woman? A writer as a life, not among objects, but dwelling in the ability to write in a relationship of concerns, with a sensibility informed by reading, contemporaries, Asian poetry and philosophy, with dispersed and located notions of place. Working from secret notes, tilting, I write of Lorine Niedecker.

My reading-based generative workshop practice has supported me in poetry, literally and figuratively. I figure as I go, as I understand the poet-of-study, in community, as a teacher. I write alongside those enrolled; I read and write with an understanding of the poet-of-study's context, from where we are in space-time, with our psychogeography and contexts. We play. The participants are writers and poets of all stripes; enrollment is open. Some call the workshops I design and lead "community-based" because participation doesn't involve earning a credit, grade, or degree, nor does it come with a gate-keeping application. "A creative event does not grasp," as Trinh T. Minh-ha writes, "it does not take possession, it is an excursion."2

I have held workshops like these for more than twenty years, based in the home I keep, with virtual participants working from and through the recordings of the in-person meeting along with supporting written and supplemental materials. I lead communities of writers through the books we read, with commentary, critical work, and writing prompts inspired by the text. We read aloud, alternating voicings, page by page. Books I have assigned, studied, taught, and written with in this series, in addition to Lorine Niedecker, have included The Maximus Poems by Charles Olson and the collected or selected works of Amiri Baraka, Anne Carson, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Joanne Kyger, H. D., Harryette Mullen, Alice Notley, Frank O'Hara, Sappho, Jack Spicer, Fred Wah, John Wieners, and C. D. Wright. I created these workshops as a "deep dive" into a full-sized, single-author text; they are designed to expand perspectives and generate new work with writing prompts, strategies, and structured writing time. We are in Austin, Texas, and we are in Toronto, Ontario, or in another elsewhere, listening remotely and reading along with the textual pages, under different weather. In the Niedecker workshop, we relate across distances in conversation with Niedecker's reading, thinking, and writing as we place ourselves or have place mark us, forming new emplacements from this relationality. Together and apart, we listen to Niedecker's voicing her poems to Cid Corman in 1970 Milwaukee via the 16-minute recording available on the internet via PennSound.

Place is not a static thing; place is an animated environment crossing boundaries of time and situatedness. It ignores imposed borders of nation even as attention to place necessarily does not ignore the violence that national borders impose. Place can be considered an expression of change, a path or process rather than a static object—as the Tao is a path necessarily related to change, as a poem might be a relational expression. Perennial like the bluestem speedwell: states of renewal, cyclical, transformation as process.

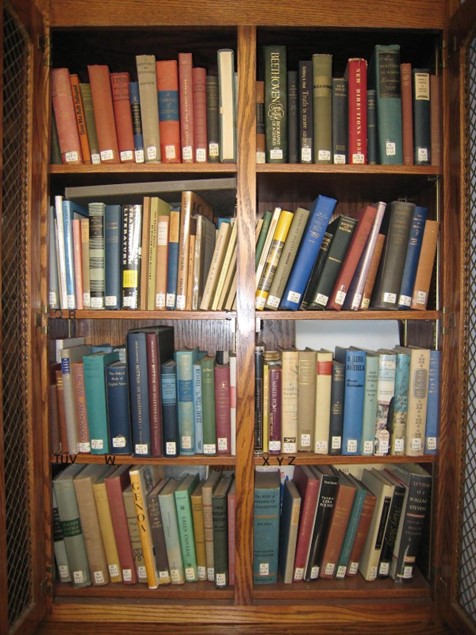

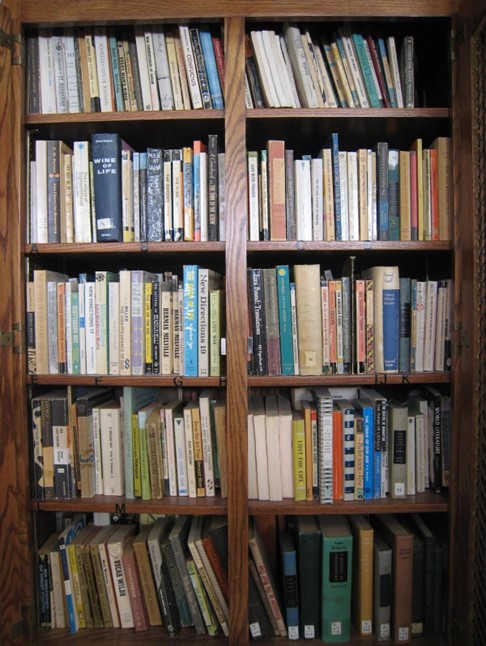

Much has been made of Niedecker's "immortal cupboard" — the tightly curated collection of books that she kept, limited by the constraints of her one-room cottage. Here the books she wanted nearby could stay; the rest she would read and then give to friends. On her shelves you can see her literary friendships and frames of reference. It's interesting to observe which books made the cut. Several were books of philosophy. Niedecker would have said "philarsophy," the way she made light of the discipline as such. Her poems pulse with studied knowing, a being with, relationality. Are all writing structures built from relationality? She had two translations of the Tao Te Ching3 in her "immortal cupboard." In one copy she comments on the philosophy she found there and provides a few words on Lao Tzu:

A sound Confucianism is the outward manifestation of Taoism (as LT himself taught it). Lao — mysticism in the form of natural truths. Havelock Ellis has the mystic's heart but also the physicist's touch and the biologist's eye.4

Niedecker also writes in this copy, translated by R. B. Blakney, that the Tao Te Ching "describes the highest good as being like water," and in it she marks a passage and paraphrases it as: "Live within yourself; do not exhaust yourself in the world as it is."5

I shared this quote with my teen sons during the pandemic, when future-gloom and catastrophe were present everyday events, even as the days took on a new ordinary. I was their age when I first encountered the Tao Te Ching in a Washington, D. C., suburb's used book store. Niedecker, too, was influenced by her reading of the Tao and Asian poetries in translation. According to Tom Montag's account on his blog The Middlewesterner, Niedecker's library contained "14 books related to Asian thought and poetry in her collection, including . . . Basho's Narrow Road to the Deep North, Kenneth Rexroth's One Hundred Poems from the Japanese, Arthur Waley's Madly Singing in the Mountains and a couple other collections of haiku, and Alan Watts' The Way of Zen."6

Dwight Foster Public Library, Fort Atkinson, WI. The books are double stacked. Photo by Hoa Nguyen, March 2009.

In Niedecker's library, she had many volumes of classical Chinese and Japanese poetry that influenced her poetics;7 she even references her reading in lines such as "Swept snow, Li Po / by dawn's 40-watt moon."8 Elsewhere she refers to that "book of old Chinese poems," which I read to be, perhaps, the anthology The White Pony.9 This influential English translation of poetry included works of Chinese poetry "from the earliest times to the present day, newly translated." This 1947 printing remained in her "immortal cupboard"; in her edition of The White Pony, she would have read the following introduction to the selection of poems by the Tang dynasty poet Li Po:

Like Blake, [Li Po] would speak in the most matter-of-fact voice imaginable of his encounters with the angels, and describe how the heavens open to receive him; but sometimes, and perhaps as a result of his extraordinary intoxication with the mere sights and sounds of the world, he would fall into profound fits of melancholy. "At fifteen," he wrote, "I ran after gods and goblins," and though he enjoyed his brief visits to fairyland, he was often inextricably caught up in a world where there was only bloodshed, avarice, corruption, and despair. For long periods he disappeared from the world, wandering through half the provinces of China[. . . . ] He seems to have liked flowers and water most, and in a line which echoes a famous prose essay by Tao Yuan-ming, he combined the two things he loved most in a single litany:

The peach-blossom follows the moving water

[ . . . ] His strength is not so apparent in English, but Chinese scholars insist that his poetry has the quality of lightning, of sudden sharp illuminations and an endless sudden tearing down of veils.10

I am struck by how Niedecker understood (would have understood? may have understood?) and inhabited this quality of Li Po, producing a poem in English after it, one that has the effect of the removal of a veil or a sudden illumination:

Something in the water

will devour

water

flower11

I taught from the Collected Works during the early pandemic, May to April 2020, each of us in our places for variable pandemic lockdown durations. I was thinking about linked histories and my relationship with Niedecker's distillation, her commitments to literary friendships and poetry. We were deep in early Zoom learning with over 100 enrolled poets reading, listening, and writing remotely. Her geographic isolation took on new meaning to us, even as her poems showed complex relations to the histories around her, how her attention turned to the local and the farther afield, to linked histories and encounter, with geologic traces and soundscapes. We threw things to the flood. Sometimes we encircled the verse with our recitation, wrapping back to hear her often short and narrow lines. In 2020, still mourning the loss of my mother the year before, I was thinking about what language teaches us, the weather and our animated world, our dreaming and reading, the relationship between language and time.

I hear the weather

through the house

or is it breathing

mother12

A few hours before the workshop in May 2020, I had what I called then a lotus vision. Can a vision come to one in a nap? Directly before the workshop — wherein we were to discuss Niedecker's relationship to war abroad, bombs, and shelters — I had a vivid plant communication dream. Lotus is the flower of Vietnam and an important emblem for Buddhism. It is a teacher, the way that plants often are. This lotus was pink or white, I can't recall now writing this. I was born in Vietnam near Saigon at the height of the war there, in the last lunation of the Fire Horse year. I would leave as a young toddler with my mother and her US American husband, my new father, a former Peace Corps volunteer who was based in Vinh Long on contract with the Agency for International Development. We had survived the Tet Offensive, me barely, having been brought to near-death in the aftermath of war destructions, made ill by tainted food or water. There were stories of several narrow escapes like these and harrowing weeks that followed the attack. In the hours before teaching Niedecker's poems, I was drawn to a passage from Jenny Penberthy's "Lorine Niedecker's Century 1903-2003":

For all the poems that use local folk speech, there are dozens more that address national and global concerns. Within the folk project of New Goose written between 1935 and 1944, there are poems about the Depression, the growth of Fascism, the Spanish Civil War, the Vichy government in France, the American involvement in World War II, plus poems that explore American history. Like all of her books, it is a blend of local and farther flung concerns, contemporary and historic.13

I had a plant communication where I dreamt of awareness as rooted in mud, deep beginning, rich and dark, mothering deep in the solar plexus. In the gorgeousness of this matrix, in food seed-mud nourishment, life force organizes, grows, gathers, and threads. It is a force of collectivity that comes together, allowing for survival for self-regulation and maturation, allowing for a blooming as a glorious burst of total and timeless consciousness. I took this vision as a message about the nature of time, ancestors, relationality, and the wisdom of plant intelligence. It lined up with the concept of The Bardo as liminal space, a concept from Buddhism and the Tibetan Book of the Dead. It's a place that is outside of time, where you are a reflection of all and nothing. Where the beloved dead can relate to us across time and place.

"We live by the urgent wave of verse," writes Niedecker, quoting Robert Duncan, in "Paean to Place."14 Reading and writing through Niedecker's Collected Works, when in workshops we reach her 393-word lyric sequence "Lake Superior," sometimes we read it aloud twice. I recommend that we consider reading the segments as separate movements or as poems unto themselves — not run-together as they are presented in the Collected. That way we encounter them as separate entities and voice each one as such, with long pauses at the asterisk to mark a duration before the next. Niedecker, in a letter to Cid Corman, said that she had wished the poems of her "Lake Superior" series could be printed on separate pages so as to be surrounded by white space. In another letter, she writes, "Strange — we are always inhabiting more than one realm of existence — but they all fit in, if the art is right."15

I offer the following prompt, based on Niedecker's influences and art. Writing alongside, alongside, you can weave along, too.

STEP ONE

Proposal

Ross Hair speaks of Niedecker as an avant-garde collagist in the folk art tradition of assemblage and draws comparisons between a gift book assemblage and the "traditional mnemonic folk and vernacular forms, including the 'curious fashion for memorial wreaths' specific to Wisconsin, that, according to Wisconsin: A Guide to the Badger State, 'were traditionally made of human hair, wax, feathers, yarn, seeds, or skeletonized leaves.'"16

The Materials

Of an Avant-Folk Wreath

Include the following:

- Photo Still Life

- Quickly find a recent photo on your phone/camera to represent an assemblage (a "still life")

- Use as reference to create tone, image, atmosphere, a "base from which to attend"

- What are "pre-owned materials"? How are they subject to transformation?

- Sound similarity: justice/just seeds

STEP TWO

Consider all materials from Step One as source for "alertness to all dimensions of untidy yet compelling realities"

Start in a pre-language space: marks on the page, shapes, meanderings

Accumulate as words, phrase, sentence

Swirl inside repetition and see where it leads you

Freely respond and weave materials

Braid/collage for an Avant-Folk Wreath

For the sake of weaving, as folk assemblage / avant collage

Free write for 20 Minutes, for 10 minutes, for an hour

Born in the lower Mekong Delta and raised in the Washington DC area, Hoa Nguyen (Twitter: @peacehearty; Threads & Instagram: @hn2626) is a poet and educator teaching poetry, writing, and poetics at Toronto Metropolitan University. Her books include Red Juice, the Griffin Prize-nominated Violet Energy Ingots, and A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure, a finalist for the National Book Award, the General Governor's Literary Award, and the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award. She's the 2024 recipient of the C.D. Wright Award in Poetry from the Foundation of Contemporary Art, an Aquarius, and a Fire Horse.

References

- Lorine Niedecker, "Paean to Place," Collected Works, ed. Jenny Penberthy (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002), 265.[⤒]

- Trinh Thi Minh-ha, "No Master Territories," When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender and Cultural Politics (New York: Routledge, 1991): 26.[⤒]

- https://lorineniedecker.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/NiedeckerLibraryupdated_000.pdf[⤒]

- Niedecker annotation in The Way of Life, translated by R. B. Blakney, circa 1955. Collection of the Dwight Foster Public Library, Fort Atkinson, WI.[⤒]

- Lao Tzu, The Way of Life, trans. R. B. Blakney (New York: The New American Library, 1955): 105.[⤒]

- Tom Montag, "Lorine's Library: Books & Marginalia in the Library of Lorine Niedecker," The Middlewesterner (June 7, 2004), http://www.middlewesterner.com/2004/06/notes-from-vagabond-journal-driving.html.[⤒]

- The known haiku books in her library, as listed in Margot Peters's bibliography, include Bashō, The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches, trans. Nobuyuki Yuasa (Baltimore: Penguin, 1966); Harold G. Henderson, trans. An Introduction to Haiku. Garden City (New York: Doubleday, 1958); Japanese Haiku, Series III: Cherry Blossoms (Mount Vernon, New York: Peter Pauper Press, 1960); Kenneth Rexroth, trans. One Hundred Poems from the Japanese (New York: Charles E. Tuttle, 1955); and Harold Stewart, trans. A Net of Fireflies: Anthology of 320 Japanese Haiku (Rutland, Vermont and Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, 1960). Source: https://lorineniedecker.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/NiedeckerLibraryupdated_000.pdf[⤒]

- Niedecker, Collected Works, 126.[⤒]

- Niedecker, Collected Works, 157-158.

The death of my poor father

leaves debts

and two small houses.

To settle this estate

a thousand fees arise—

I enrich the law.

Before my own death is certified,

recorded, final judgement

judged

taxes taxed

I shall own a book

of old Chinese poems

and binoculars

to probe the river trees.[⤒] - Robert Payne, editor, The White Pony: An Anthology of Chinese Poetry from the Earliest Times to the Present Day Newly Translated (New York: John Day, 1947), 159-160.[⤒]

- Niedecker, Collected Works, 202.[⤒]

- Niedecker, "Thure Kumlien,"Collected Works, 150.[⤒]

- Jenny Penberthy, "Lorine Niedecker's Century 1903-2003," What Region? 1, no. 1 (May 2015): 13.[⤒]

- Niedecker, "Paean to Place," Collected Works, 265.[⤒]

- Lorine Niedecker, "Between Your House and Mine": The Letters of Lorine Niedecker to Cid Corman, 1960-1970, ed. Lisa Pater Faranda (Durham: Duke University Press, 1986): 92.[⤒]

- Ross Hair, "The Avant-Folkways of Lorine Niedecker." Avant-Folk: Small Press Poetry Networks from 1950 to the Present (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2016): 63.[⤒]