Locating Lorine Niedecker

Lorine is not Bette nor Billie nor Marlene nor Lena nor Joan nor Judy. But, she is a queer icon. Niedecker's iconicity stems from the distinctiveness of her habitus and style — such that she is situated, in the realm of poetry, alongside Dickinson, Whitman, Stein, O'Hara, Angelou, and Plath.1 From her spare hermitage along the Rock River — for so many years just herself, books, and birdsong, tethered to the art world by flood-perfumed letters — issued disconcertingly original verse that combines the top-of-head-taking originality of Dickinson, Bashō's profound whimsy and exquisite concision, the breath-blown forms of Objectivism, and a capricious application of Marx. To describe her in such terms condenses Niedecker to the "largely sentimental image" that Douglas Crase rightly argues has occluded our view of her true complexity.2 Niedecker, however, is happy to engage in such essentializing characterizations herself: in "If I were a bird" she provides a series of portraits in miniature, wherein her avian avatar is styled after the poetics of her contemporaries, such as H. D. in the first stanza:

I'd be a dainty contained cool

Greek figurette

on a morning shore —

H.D.3

Figuring H. D. as a "dainty" Doric caricature, Niedecker compresses her modernist predecessor's stylistic evolution from the Imagism of Sea Garden (1916) to the laments and mystic transpositions of Trilogy (1942-1944) into the totemically "contained," period-studded initials of the fourth line. This act of evocative encapsulation points to how possessing an accountable repertoire of characteristic signs or gestures facilitates the queerest form of affection: emulation.

In the essay that follows, I argue for the importance of Niedecker's entanglement with queer figures, who helped mold her thoughts on gender relations, and the enrichment of her art by a queer aesthetic she herself sought to evoke and transform. I follow the ramifications of these attachments by attending to how the poet and publisher Jonathan Williams attempted to enshrine Niedecker within a modernist counter-canon and accomplished feats of what I conceptualize as lyric drag in poems about and styled after Niedecker. Williams not only connects his legacy with the sustenance of hers, but he also dons the homespun fabric of Niedecker's imitable poetic sensibility. Distinct from the dramatic monologue, this mode of homage does not emphasize writing as the diva (although slippage into persona can be tempting), but rather writing the poem as the diva might have written it herself. Just as the conditional and subjunctive moods in "If I were a bird" point to the notional rather than actual, this mode of expressivity adverts to the very fictivity that undergirds the lyric. To adapt Judith Butler when she considers the denaturing of gender effected by drag performance: lyric drag implicitly reveals the imitative structure of lyric itself — as well as its contingency.4 To wit: Niedecker writes she would "poise" herself as a cuckoo-like mimic in blushing plumes, supported by the Floridian fabulism and polysyllabic flamboyance of Wallace Stevens's imaginary: "On Stevens' fictive sibilant hibiscus flower / I'd poise myself, a cuckoo, flamingo-pink."5 Even as, to quote another of Niedecker's targets, "one discovers that there is in / it after all, a place for the genuine,"6 the goal of lyric drag is not authenticity but an ersatz realness that is always winking at its irreality.

Entanglements

The realms of Niedecker's existence were gender segregated — zones of homosociality she either heroically violated or resignedly joined. In her artistic life, she was often the only woman in the room, actually or figuratively, whereas her workaday world, as Sarah Dimick explores in her essay on Niedecker's janitorial labors at Fort Atkinson Memorial Hospital, was feminine. Although she did take some local women as friends, she jokingly aired anxieties in letters about the possible revelation of her deviance from normative expectations — "I could do some good in this community once I'd overcome their feeling that I was a freak" — while also taking pleasure in the "difference" afforded by her quixotic avocation.7 This sense of living estranged from society pervades Niedecker's corpus, and it is this concealed alterity that attracts her queer admirers. As Wayne Koestenbaum writes of the "codes of diva conduct" in The Queen's Throat, there is a hope that the diva might "assist gay self-authorization because she is a deviant figure," sharing the power she derives from her freakish exceptionalism.8 Indeed, like many divas, Niedecker's closest relationships outside her family — both romantic and platonic — were with putatively queer men.

An inconspicuous line courses through Margot Peters's biography Lorine Niedecker: A Poet's Life, drawing together the men — save for Cid Corman and her second husband Al Millen — who had the largest impacts on Niedecker's life. How the specter of homosexuality attends the figures of her first husband Frank Hartwig and her mentor Louis Zukofsky, as detailed by Peters, tempers our understanding of how each shaped Niedecker's social world, its extensions and contractions. Hartwig, as the photo taken nine months into their marriage reveals, was affably handsome, tanned, and broad-shouldered, a farmer's son who had worked with Lorine's father Henry seining carp on the Rock River. The reasons for their betrothal as well as the union's failure, resulting in an amiable twelve-year-long separation and eventual divorce in 1942, puzzled Niedecker's friends and scholars alike. Economic factors played an important role in the arrangement's dissolution; the crash of 1929 ended their cohabitation, with each retreating to parental abode. In a 1987 interview co-conducted by Gail Roub (Niedecker's neighbor and close friend whom Lorine's second husband Al, Peters tells us, jealously accused of being homosexual and drunkenly threatened with a gun) and his wife Bonnie,9 Frank's brother Ernest Hartwig contends Frank would not have "interfered" with Niedecker's poetic ambitions, only hesitantly agreeing to Bonnie's suggestion that Lorine's restlessness obliged the union's termination.10 Peters, however, points to sexual incompatibility, in more ways than one, speculating in a parenthetical stage whisper:

(There is another possibility. Frank never dated a woman before Lorine, Ernest was incredulous that he married, he never dated a woman after Lorine, he accepted the failed marriage without protest, and he never blamed Lorine for leaving him. If Frank Hartwig were homosexual it would put an entirely different slant on Lorine's reported, "If that's all it amounts to in marriage, it's not for me.")11

The poet is coy about what "it" might denote in her remark to friend Nathalie Kaufman Yackels, and in that vagueness Peters inserts her supposition. In her reading of Niedecker's anti-marriage poems of the 1940s and '50s such as "I rose from marsh mud" and "So you're married young man,"12 Jane Augustine finds that the gender and sexual roles undergirding heterosexual marriage constitute "moral degradation" for someone like Lorine (and, I want to add, if the "possibility" holds, for someone like Frank, too).13

While still technically Mrs. Frank Hartwig, Niedecker began corresponding with Zukofsky after reading his February 1931 Objectivist issue of Poetry, assembled while he taught at the University of Wisconsin. In advancing his poetic program, Zukofsky extends his "[d]esire for what is objectively perfect" to embrace queer predecessors and contemporaries like Arthur Rimbaud, John Wheelwright, and Whittaker Chambers.14 Most provocatively, in this regard, the penultimate contribution to the issue is a three-way "symposium" between LZ and queer collaborators Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler. The latter's Priapic "Hymn" constructs a "fixed symbolic scheme" whose perfected object is an ejaculating penis, "in which / growth of the sensual face / creeps from the creamy white stalk."15 Sighting the homosocial milieu into which she wished to be transplanted, Niedecker courted Zukofsky and sought to establish, to his dismay, a ménage with this charming advocate for "clear or vital particulars" in Greenwich Village in late 1933. Perhaps unbeknownst to Niedecker (although one wonders what truths his requested destruction of their early correspondence ultimately concealed), Zukofsky had an active, apparently bisexual erotic life. As detailed by Peters, Zukofsky's bedfellows included the "'sexually predatory' Ezra Pound" and his own protégé and former student Jerry Reisman.16 Pound had cruised Zukofsky by letter — writing with the impertinent "queery," "Can jewish gentlemen meet sodomitical gentlemen in New York without the irritations of interactive prejudice, or do ONLY jewish sodolitical [sic] gentlemen meet sodomitical gentlemen of other religious persuasions???"17 — before bedding Zukofsky in Rapallo a few months before Niedecker's arrival in New York.

published in Niedecker and the Correspondence with Zukofsky, 1931-1970, ed. Jenny Penberthy

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 53.

Given the ensuing anguish of romantic misunderstanding, unexpected pregnancy, compelled abortion, and manipulation that marred her relationship with Zukofsky, it is somewhat remarkable that Niedecker's feelings for him endured beyond 1935. And yet, missing Lorine, Zukofsky, with Reisman in tow, visited her on Blackhawk Island in 1936. Captured on Lake Koshkonong, his averted gaze resembling Niedecker's in the June 1929 photo with Hartwig, Reisman rests an arm proprietarily on the thin shoulders of his mentor and sometimes-collaborator, who pulls a faux-serious face, abask in adulation. Snared in the seine of Zukofsky's charisma, Niedecker and Reisman are triangulated, made proximate through desire. One imagines Lorine wielding the camera, training its glass eye — capable of clarities unknown to her — at these two men whose intimacy might have felt to her relatively uncomplicated, alluring, impossible.

Enrichments

Ophelia kept rue for herself. Bestowing grace, symbolizing regret, its fragrant oils are apotropaic — and abortifacient. In his brief memoir of Niedecker, Reisman writes, "Lorine ruefully named [her aborted twins] 'Lost' and 'Found.'"18 Although Carl Rakosi urged Zukofsky to marry composer Celia Thaew, as Margot Peters puts it, to "erase his previous homosexuality,"19 the scars of Niedecker's dalliance with the Objectivist proved less delible, with Reisman writing that she "must have ached for those twins all the years of her life."20 Given how unanticipated pregnancy and the loss of children (even if only rumors) haunted both her relationships with Frank and LZ, Lorine no doubt affixed special import to Ophelia, that spurned, singing maiden lost to the flood. Hamlet, in fact, was the only individual Shakespeare play housed in her "immortal cupboard."

Turning to Niedecker's repository of influences, we learn that Zukofsky was not alone in having the roots of his poetics firmly planted in the richesse of queer style. Works by John Cage, Aaron Copland, Robert Duncan, Allen Ginsberg, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Henry James, Ronald Johnson, Katherine Mansfield, Herman Melville, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Marianne Moore, Arthur Rimbaud, George Santayana, Sappho, John Addington Symonds, Walt Whitman, Oscar Wilde, and Jonathan Williams all number among Niedecker's treasured volumes.21 What is revealed from this survey comes as no surprise to those familiar with Niedecker's long poems and the extensive study that fueled her "condensery," an immersive erudition that produces the "sensuousness," as Douglas Crase pinpoints it, that distinguishes Niedecker from her Objectivist peers.22 From her perusal precipitates a series of miniature poetic portraits from the early 1960s that serve as meditations on the sympathetic circumstances connecting Niedecker to her queer heroes — including "T. E. Lawerence" (on loneliness) and the "Henry James" segment from "Florida" (on being duped by romance). These poems are discrete from lyric drag in their refusal of stylistic imitation. Included in her gift-books of Homemade/Handmade Poems that Niedecker sent to her closest literary friends in 1964, "Santayana's" is the most developed of these poetic portraits. It condenses language from a letter the philosopher sent to his secretary Daniel Cory, in which he beseeches the younger man to dissuade Ezra Pound from foisting his poetry upon him:

For heaven's sake, dear Cory,

poetry? — I like somewhat

the putrid Petrarch

and the miserable Milton.

I don't have books,

don't meet important persons

only an occasional stray student

or an old Boston lady.23

The title's possessive signaling her appropriation, Niedecker was doubtlessly "attracted to the playful exaggeration of [Santayana's] pose,"24 as Jenny Penberthy writes; the philosopher's ostentatious alliteration — "putrid Petrarch" and "miserable Milton" — and petulant tone refuse the possibility of protégé(e)-mentor dialogue that Zukofsky sought with Pound and Niedecker sought with Zukofsky. The letter poem also collapses Santayana's cosmopolitanism into elective introversion (also attractive to Niedecker). Although she takes his epistolary language as poetical material, Niedecker does not heed Santayana's advice in Reason in Art on the perpetuation of art through the mechanisms of stylistic emulation: "It is no longer merely hidden inner processes that [the poet] must reproduce to attain his predecessor's wisdom; he may acquire much of it more expeditiously by imitating their outward habit — an imitation which, furthermore, they have some means of exacting from him."25 Instead of reproducing the regular meters and "rational" forms of Santayana's poetry, Niedecker adopts his pose by adapting and shaping his prose according to her own excisive eye and ear. The expressive thrift that results aligns Niedecker with the disciplinary refinements of minimalism. Although she keeps her "inner processes" largely concealed, Niedecker was a poet schooled in the decadents and aesthetes as well as the pragmatists, and the words that appear on the page are costly, representing a great luxuriance of time. Although he exaggerates, Jonathan Williams attests to this temporal excess: "About one poem, like the frailest peony blossom, drops from Lorine Niedecker's typewriter every year."26 Lavishing phrases with attention for untold hours all to convey a sense of spontaneity — which her beloved Santayana argued "justified" poetry27 — what better affirms Niedecker's status as grand artificer, who transmutes indulgence into eloquence?

Enshrinements

Jonathan Williams, Niedecker's eventual publisher, was one recipient of Handmade Poems. A "loco logodaedalist" who aspired to the eccentric condition of country squire qua gentleman of letters, Williams proved to be, along with Cid Corman, Niedecker's most steadfast champion. In Niedecker, Williams found a kindred spirit who transposed, without condescension, the charm and linguistic ingenuity of country folk into an avant-garde idiom. These rural stalwarts both tune their lyres to reproduce the dialectal quirks and textures of anti-normative speech. As Ross Hair argues in Avant-Folk, the "resistant 'folkways'" that Williams and Niedecker catalogue — and here I include gossip, eggcorn, malapropism, mumpsimus, eye dialect, and both plain and embroidered speech — subvert the homogenizing regimes of mainstream media and literary modernism.28 They exhibit a receptivity to forms of expressive deviation that are marked by a sonic rightness that is instinctual rather than contrived. Just as he collected vernacular "foundlings," bad puns, and sesquipedalian oddments on his rambles through Appalachia and the English countryside in his poetry, Williams inducted Niedecker into the Jargon Society's constellation of outsiders. Re-invoking his jacket blurb for T & G: The Collected Poems (1969) published by Jargon, Williams proclaims Niedecker "the most absolute poetess since Emily Dickinson" in describing his 1967 portrait.29

published in A Palpable Elysium: Portraits of Genius and Solitude (Boston: David R. Godine, 2002), 63.

I treat this image — a diva in situ — ekphrastically in my contribution to The Marsh folio accompanying this cluster. Although the Milwaukee portrait would seem to occupy a wholly different register, it exemplifies Williams's investment in diva self-fashioning as much as his most obvious turn at lyric drag in "The Apocryphal, Oracular Yeah-Sayings of the Ersatz Mae West." In that poem, the zaftig patron saint of "smalltown faggot psychology"30 fictitiously retorts to Old Ez' Pound, "An ounce of erection is worth a pound of allure."31 One imagines Santayana would concur with Williams's ventriloquism.

In his emulations of Niedecker, Williams is not quite so saucy, but he is sincere in his affect(at)ions. One such homage originally featured in Epitaphs for Lorine (1973), the Gedenkschrift Williams edited, and later included among the "Homages, Elegies & Valedictions" section of his final collection Jubilant Thicket and titled as "Still Water for Lorine Niedecker (1903-1970)." This foray into lyric drag finds Williams trading his boisterous, country-fried version of Black Mountain projectivism and the formal constraints of his "meta-fours" for Niedecker's honed idiolect and variable line. He knows that the true measure of diva expressivity lies in marshalled silences, in the knowing of when to stint and when to swell:

she seined words

as others stars

or carp

laconic as

a pebble

in the Rock River

along the bank

where the peony flowers

fall

her tall friend

the pine tree

is still there

to see32

The logic of lyric drag contends that to write about Niedecker's method compels writing like Niedecker, for Williams to become "laconic as / a pebble" himself. Adopting the fragmentary syntax of Niedecker's post-Objectivist lyrics of the early 1960s, he evokes the poet's process of instantiation through language from inside that process, with the labor of seining/signing figured as both material and "mystic-sensual," to borrow Niedecker's phrase.33 The glimmer in one's net might be scale or star. The poem's entextualization as an "epitaph" mediates the possibility of synthesis with its model, providing the opportunity to revisit and remediate Niedecker's work. In this regard, the penultimate stanza evokes both "My friend tree" and the anti-marriage poem "The men leave the car," in which Niedecker grieves "against a large pine-spread" as the masculine woods echo with the sound of "No marriage / friend."34 In Williams's reimagination, the arboreal "friend" — like the queer one — proves faithful, persisting as witness to the poet's mythopoetic transformation into fragrant bloom.

The occasion of lyric drag — and its instantiations are typically occasional poems — is vaguely disreputable. Ancillary to the "proper" task of lyric expression, wherein the sense of the voice as cynosure of individuation is affirmed, lyric drag destabilizes this tidy schema through its performative embrace of improper subject-object relations. As in most drag performances, subtlety does not characterize its allusions; there is a tendency to announce — by title, dedication, or apostrophic address — the object of one's homage, as though the poet seeks diva intercession as he intercedes on the diva's behalf. Thus, lyric drag's imitations shore up the self through contingency, drawing expressive and self-actualizing potentiality via its evocation of a "poetess" seemingly capable of granting her own sovereignty. And yet, as Williams's "Six Misericords for LN in Misericordless Wisconsin" demonstrates, the avowal of diva autonomy is a tactic that obscures the reciprocal exchanges undergirding the cathexis of diva worship. The concluding entry in The Full Note: Lorine Niedecker (1983) — a selection of poems, letters, critical appraisals, and poetic tributes edited by Peter Dent that serves as the British equivalent of Epitaphs for Lorine — Williams's poem is modeled after the late great lyric sequences that would appear in Jargon's From This Condensery: The Complete Writing of Lorine Niedecker (1985), such as "Lake Superior," "Thomas Jefferson," and "Traces of Living Things." Creating a progression whose fragments achieve conceptual unity through pictorial logic and semantic meander, Williams commences with two images of feminine agency:

Misericord (1)

a dignified figure

seated at a desk

with a large bird

beside her

and the head

of either a snake

or a small dog

emerging from the sleeve

of her loose robe

Misericord (2)

virago

in a barrow35

Just as "Still Water" depicts Niedecker's poetic labors as a means of symbolically reconciling her paternal and maternal inheritances and inclinations — the effortfully seined carp and the sensuous peony bush — the first and second "Misericords" hinge on representations of gender crossing and conflation. In the former, Williams does not channel Niedecker's voice, but offers what could be Niedecker's "dignified figure," portrayed (com)posing as in a formal desk portrait typical of an esteemed belletrist or natural philosopher. A magus, she works wonders as a familiar's face emerges "from the sleeve / of her loose robe." In the second section, the puffed or "virago" sleeve transforms, through lexical legerdemain and visual suggestion, into the mound of a "barrow," a tumulus interring a "manlike" Iron Age queen.

Constructing his polyptych, Williams deploys the ekphrastic mode — uncommon, but not unknown in Niedecker's oeuvre — to bridge media, locales, and temporalities. As John Latta observes with characteristic acuity in an Isola di Rifiuti blog post on this "ephemeral poem," which has not been collected in any other volume, Williams invokes the definition of misericords as "detailed, often bawdy, carvings of scenes of daily life" that grace the shelf-like ledge hidden underneath the folding seats of medieval choir-stalls.36 Supporting the infirm during sustained periods of worship, these "mercy seats" frequently feature folk allegories and fantastic creatures, such as unicorns, dragons, cockatrices, wild men, and anthropomorphic animals; Williams's renditions are considerably more mundane. His Mae West poem announcing its "ersatz" nature explicitly, Williams here subtly conceals the poem's artifice beneath a congenial veneer of naturalism. Consulting Williams's daybook, Latta convincingly connects the Niedecker tribute to the sixty-eight misericords of Beverley Minster, whose vicar advised Williams to make a pilgrimage and inspect the carvings himself.37 It is unclear whether Williams made the trip from Corn Close, his cottage in Dentdale, as his images veer from the sixteenth-century exemplars.

This much is clear: in the act of bestowing the merciful "Misericords" to Niedecker, Williams tries to match her sensibilities. For instance, through the open-endedness of the fragment and the resignification facilitated by lyric drag, Williams subtly redresses misogyny: the "crone wheeled by her man in the barrow" trope exemplified among the Beverley misericords, which art historian Malcolm Jones identifies as deriving from the conventions of Germanic anti-feminist satire,38 is remediated. We are encouraged by the fragment's contextualization to view the ascription of viraginity as celebrating Niedecker's fierce independence and virtus, placing her, despite her pacifism and placid demeanor, in the legendary precincts of a gender-transgressing woman warrior. Williams's reflective evocations promiscuously interweave the actual and notional, constituting a spectrum of gendered activities as they move from feminine singularity to masculine plurality:

Misericord (3)

hammering a wedge

to split

a hedge-stake

Misericord (4)

his right hand is

broadcasting seed

a horse

walks behind

Misericord (5)

what

no doubt

was a hawk

on his wrist

Misericord (6)

two men

hold partly filled sacks

and a long corn bin

as they kneel behind

a pile of grain39

Rather than exhibiting the "ekphrastic hope" that W. J. T. Mitchell describes in Picture Theory as the poem's aspirations to medial mastery, an impossibly lossless transmutation from the visual to the verbal,40 Williams here marshals polysemy (e.g., the multiple meanings of misericord, virago, barrow) and indeterminacy to extend media boundaries rather than guard them. In terms of the latter quality, much of the poem's creative power lies in piecing out what might be perceivable (perhaps in homage to Niedecker's impaired sight) from an image that might not represent a material artifact.

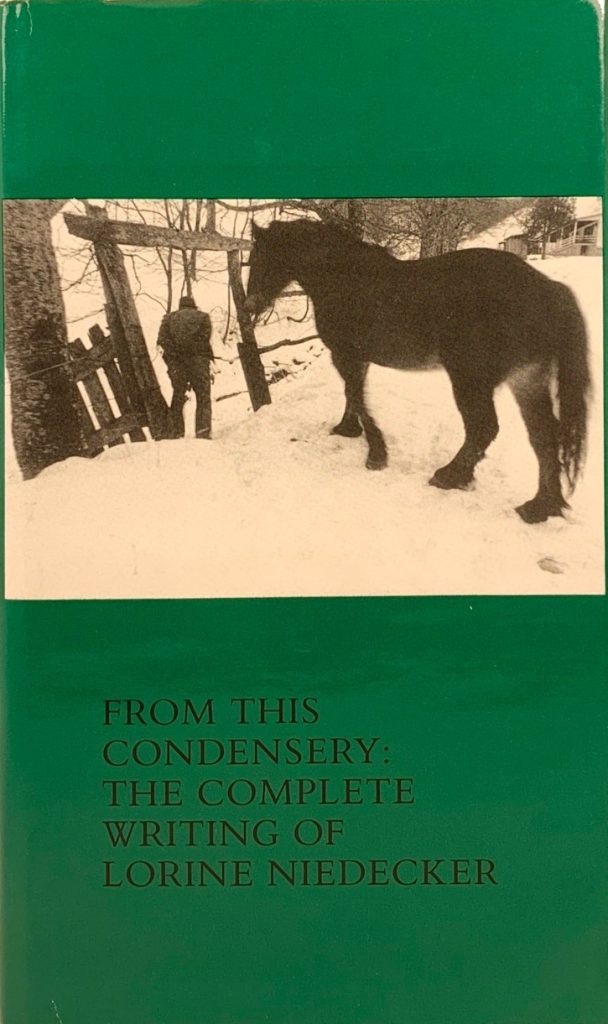

Ambiguity of scene and generality of referent allows Williams to triangulate the dales and parish churches of Yorkshire, his home in North Carolina's Blue Ridge Mountains, and Blackhawk Island into rural commonplace. For instance, "Misericord (4)" seemingly depicts the Rob Amberg photograph Junior Walking Pet to Water that serves as the cover image for Niedecker's From This Condensery.

In this selection from Amberg's Sodom Laurel Album series, broad haunches blur as the draft horse "walks behind" the hunched man across borderless snows — conjuring Wisconsin gelidity in the Southern Appalachians — toward the satisfaction of its desires. This last term is imperative: with innuendo and double entendre ("hammering a wedge," "broadcasting seed," etc.) flavoring several "Misericords," clearly something queer is afoot. As men grip half-filled "sacks" and "kneel behind / a pile" of intermingling seed, their purpose unclear, at the poem's conclusion (which is linked to "Misericord (4)" by its clausal independence and repetition of "behind"), Williams offers homosocial intimacy as a condition of reality, one among the many, to which Niedecker might affix her approving cypher. In this regard, the poet extends care to the authorial self through a reflexivity inhered within lyric drag's oblations, that the networked affinities they gather too might enjoy the diva's benevolent regard and thereby mutually escape misericordless states.

In Exchange for Conclusion

Anatomizing the full extent of Niedecker's engagement with queerness requires elaboration beyond this essay's scope. Her entanglements with Frank Hartwig and Louis Zukofsky, her immersion in queer poetics, and the acts of lyric drag by Jonathan Williams that I have examined here attest nonetheless to our beloved Lorine's icon status. She was a sophisticated stylist who recorded the immensities of desire that struggle to find articulation in spaces of liminality. And yet, from the margins comes a mode of expressivity that creates, through its condensation and oblique approach, occasions for greater clarity about the self. Seemingly austere, the arrangements of words on the page represent an extravagance of thought, their formulation protracted across great gulfs of time. Caught within this temporal flux, we might discover unanticipated confluences. For example, I encountered two "nominal" surprises in the course of providing my own contribution to the cultivation of Niedecker's legacy among queer men. First, I learned that the Rock River, whose waters shaped the terrain of Niedecker's existence, originates near the village of Brandon, Wisconsin. Even more astonishing: in the hush of the Hoard Historical Museum's special collections library, on the plat map detailing how Henry Neidecker had partitioned Blackhawk Island into lots, I discovered that Lorine's neighbor was a Menke, whose twenty feet of river access were the west border to the flood-prone land on which her cabin still lies. Across the highway, adjoining plots belonging to "Neidecker" and "G. Menke" are connected by a spurred line.

Fig. 5: From the 1950 Blackhawk Island plat map, depicting lands sold by Henry Neidecker, with details showing property owned by Lorine and the Menke family. Gail Roub Niedecker Collection 003.19.244, Hoard Historical Museum, Fort Atkinson, WI. (Photo: Brandon Menke)

My grandmother's name is Lorene, with two e's, from the Latin for "bay laurel." This coincidence has always afforded Niedecker a special fondness for me, but I never expected to encounter my familial name — which, like Neidecker (the familial spelling), traveled to the Midwest from its origins in North Rhine-Westphalia — in such striking proximity. A firm believer in what Susan Howe calls the "telepathy of archives," I became snagged on that spurred line. Opening myself to the unbidden, which poetry so readily facilitates, I became susceptible to associative deluge, when "the unreality of what seems most real floods over us."41 In the wash of particularities, lyric drag appears as a line of queer affection and survival, intertwining the denatured idiosyncrasies of style and sincere attachment. It draws us toward the "most real" by serving us a realness that is most efficacious when most irreal and imitative.

Niedecker has been duly celebrated as one of the finest nature poets writing in our American idiom, as a champion of folk authenticity. But, as Douglas Crase points out, Niedecker's lasting intervention consisted of elaborating the marginal, a "simple but radical act of paying attention to realities no one else was bothering to see."42 Lyric drag sees her as a poet who shrewdly and ruefully treats those pleasures and vicissitudes of human experience that have so often been figured as freakish or unnatural — in all of their odd diversity and joy.

Brandon Menke Brandon Menke (Twitter: @bamenke; Instagram: @queer_lyricism) is a poet and scholar of queer art and literature. He is assistant professor of English at the University of Notre Dame. His creative and critical work is found or forthcoming in Poetry, The Yale Review, Denver Quarterly, and the edited volume Elegy Today: Revisions, Rejections, Re-mappings.

References

- It should be noted, given the focus of this essay, that Angelou is the only one of those listed to be portrayed through drag on national television by no fewer than four performers: Tracy Morgan gave a deadpan rendition on Saturday Night Live coinciding with the launch of Angelou's Hallmark line; Colman Domingo repeatedly depicted "America's treasure" reciting raunchy M4M personal ads from Craigslist on the Big Gay Sketch Show; and both Monét X Change and Chi Chi Devayne (requiescat in pace) depicted Mother Maya, with varying degrees of finesse, as "Snatch Game" contestants on RuPaul's Drag Race Season 10 and All Stars Season 3.[⤒]

- Douglas Crase, "Free and Clean," On Autumn Lake: The Collected Essays (New York: Nightboat Books, 2022), 57.[⤒]

- Lorine Niedecker, Collected Works, ed. Jenny Penberthy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 130.[⤒]

- Consult Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1990), 134-139.[⤒]

- Lorine Niedecker, Collected Works, 130.[⤒]

- Marianne Moore, "Poetry," The Poems of Marianne Moore, ed. Grace Schulman (New York: Penguin, 2005), 135.[⤒]

- Lorine Niedecker, Letter to Zukofsky dated March 10, 1958, Niedecker and the Correspondence with Zukofsky 1931-1970, ed. Jenny Penberthy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 244.[⤒]

- Wayne Koestenbaum, The Queen's Throat: Opera, Homosexuality, and the Mystery of Desire (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 1993), 105.[⤒]

- Margot Peters, Lorine Niedecker: A Poet's Life (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2011), 197.[⤒]

- Taped and transcribed by Gail Roub, January 6, 1987, Hoard Historical Museum, Fort Atkinson. https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/ANNMBQJ3Z2XZOA85[⤒]

- Margot Peters, Lorine Niedecker, 30.[⤒]

- Consult Jane Augustine, "'What's Wrong with Marriage': Lorine Niedecker's Struggle with Gender Roles," Lorine Niedecker: Woman and Poet, ed. Jenny Penberthy (Orono: National Poetry Foundation, 1996), 139-156.[⤒]

- Augustine, Lorine Niedecker: Woman and Poet, 142.[⤒]

- Louis Zukofsky, "Program: 'Objectivists,'" Poetry 37.5 (Feb. 1931), 268.[⤒]

- Parker Tyler, "Hymn," Poetry 37.5 (Feb. 1931), 285-287.[⤒]

- Margot Peters, Lorine Niedecker, 40.[⤒]

- Quoted in Nick Salvato's ingenious "Bottoming Zukofsky," in which Salvato argues that "Zukofsky's turn from normative dramatic conventions entails a concomitant turn from normative sexuality." Salvato, Uncloseting Drama: Modernism's Queer Theatres (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 62-63.[⤒]

- Jerry Reisman, "Lorine: Some Memories of a Friend," Lorine Niedecker: Woman and Poet, ed. Jenny Penberthy (Orono: National Poetry Foundation, 1996), 36. My emphasis.[⤒]

- Margot Peters, Lorine Niedecker, 61.[⤒]

- Jerry Reisman, "Lorine: Some Memories of a Friend," 36.[⤒]

- The Friends of Niedecker have a searchable database here: https://lorineniedecker.org/research/resource-database/[⤒]

- Douglas Crase, "Free and Clean," 63.[⤒]

- Niedecker, Collected Works, 203.[⤒]

- Jenny Penberthy, "Later Years," Niedecker and the Correspondence with Zukofsky 1931-1970 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 87.[⤒]

- George Santayana, The Life of Reason; or, The Phases of Human Progress: Reason in Art (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1922), 14.[⤒]

- Jonathan Williams, "'Think What's Got Away in My Life!,'" The Magpie's Bagpipe: Selected Essays of Jonathan Williams, ed. Thomas Meyer (San Francisco: North Point Press, 1982), 22.[⤒]

- George Santayana, The Life of Reason; or, The Phases of Human Progress: Reason in Art, 106.[⤒]

- Ross Hair, "Jonathan Williams: Beyond Black Mountain," Avant-Folk: Small Press Poetry Networks from 1950 to the Present (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2016), 125.[⤒]

- Jonathan Williams, A Palpable Elysium: Portraits of Genius and Solitude (Boston: David R. Godine, 2002), 62.[⤒]

- As Frank O'Hara was reputed to describe West, quoted in Wayne Koestenbaum, The Queen's Throat, 91.[⤒]

- Jonathan Williams, The Loco Logodaedalist In Situ: Selected Poems 1968-70 (London: Cape Goliard Press, 1972), no page.[⤒]

- Jonathan Williams, Epitaphs for Lorine, ed. Jonathan Williams (Penland: The Jargon Society, 1973), no page.[⤒]

- From a letter from Niedecker to Clayton Eshleman, quoted in Rachel Blau DuPlessis, "Lorine Niedecker's 'Paean to Place' and Its Reflective Fusions," Radical Vernacular: Lorine Niedecker and the Poetics of Place, ed. Elizabeth Willis (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2008), 157.[⤒]

- Lorine Niedecker, Collected Works, 190.[⤒]

- Jonathan Williams, The Full Note: Lorine Niedecker, ed. Peter Dent (Devon: Interim Press, 1983), 96.[⤒]

- John Latta, "Lorine Niedecker / Jonathan Williams," Isola di Rifiuti 21 Mar. 2012 http://isola-di-rifiuti.blogspot.com/2012/03/lorine-niedecker-jonathan-williams.html[⤒]

- John Latta, "Lorine Niedecker / Jonathan Williams," no page.[⤒]

- Malcolm Haydn Jones, "The Misericords of Beverley Minster: a Corpus of Folkloric Imagery and Its Cultural Milieu, with Special Reference to the Influence of Northern European Iconography on Late Medieval and Early Modern English Woodwork," PhD diss., (University of Plymouth, 1991), 160, 213.[⤒]

- Jonathan Williams, The Full Note: Lorine Niedecker, 96-97.[⤒]

- W. J. T. Mitchell, Picture Theory: Essays on Visual and Verbal Representation (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1994), 152-155.[⤒]

- Susan Howe, Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of Archives (New York: New Directions, 2014), 63.[⤒]

- Douglas Crase, "Note on Niedecker," On Autumn Lake: The Collected Essays, 56.[⤒]