Contemporary Literature from the Classroom

I. Introduction (JR and CLM)

This essay is co-authored by John Roache, a "teaching-focused" Lecturer in English Literature at a UK university, and Cyrus Larcombe Moore, a poet and recent graduate of the same university. It emerges out of a third-year undergraduate course called "Culture and Marginality," recently designed and taught by John, in which Cyrus was a member of the inaugural student cohort.

The first section, written from John's perspective, outlines a number of the intellectual and political questions that informed his approach to teaching his "own" research (on the relationship between putatively "textual" and socio-political forms of marginality) for the first time. More specifically, it focuses on his decision to teach forms of digital media and Artificial Intelligence (AI) that were relatively unfamiliar to him, and yet seemed to have the potential not only to speak to a range of intellectual questions covered elsewhere on the course, but also to help redress the prevailing tendency, as analysed in Rachel Sagner Buurma and Laura Heffernan's 2020 study The Teaching Archive, to privilege the work of "research" over that of "teaching" in the majority of historical accounts of the emergence and development of English Literature as a modern academic subject.1

The second section, meanwhile, is adapted from the essay that Cyrus wrote as part of his final assessment on the course. Rather than following directly from the first section in a relatively conventional (or "essayistic") way, this section might instead be read as an example of the kind of student responses that emerged out of the "de-centered" and collaborative conditions that prevailed — at least in part! — during this first iteration of the course. Cyrus's main argument is not only that such conditions should ideally become more prevalent in contemporary humanities classrooms, but also that, especially when encountered in combination with an increased focus on digital media and AI, they can give us a model for a more explicitly 'de-hierarchized' and interdisciplinary version of English Literature itself — one with the potential to help address the subject's current struggles to sustain student recruitment levels in both the UK and elsewhere.

Another claim Cyrus makes is that the "outputs" offered by Large Language Models (LLMs) (such as Open AI's GPT and Google's Bard) might productively be read as "multi-authored" "aggregations" of a range of relatively hegemonic (or "central") ideological perspectives. If, by a kind of pedagogical analogy, this might also enable us to read the kind of "outputs" produced by such presumptively "open" and de-hierarchized classroom discussions as similarly "aggregated," it is our hope, nonetheless, that these latter have the potential not only to undercut the language of "autonomous" neoliberal individualism that is so often reproduced by current LLMs, but also to offer a perspective capable of challenging precisely the kinds of hegemonic norms that seem to come "baked into" the vast majority of mass-marketed AI technologies today.

It is in this final sense that the authors would also like to invite readings of the current essay as itself just such a kind of "aggregated," collaborative output: while each of the following sections "centers" one of our individual perspectives, and maintains more or less wholesale our idiosyncratic written "styles," we nonetheless hope that by effectively "shuttling" between the two, the essay can not only narrate something of that critical "displacemen" of center and margin entreated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak,2 but also help to illuminate the myriad (if often invisible) ways in which the work of research and teaching might be seen as inextricably "woven together" in the contemporary humanities classroom.3

II. A lecturer's perspective (JR)

On taking up a "permanent" teaching-focused lectureship at a UK-based university in September 2022, one of my first tasks was to design a third-year course based on my research on the relationship between putatively "textual" and "other" (social, political, historical) forms of "marginality" since the late nineteenth century.4 While there's no denying that I was excited to teach my "own" specialism for the first time (after six years of precarious contracts teaching mostly the research of others), such an opportunity also highlighted a number of intellectual and professional questions about which I'd been thinking for some time. How far do the growing number of academics on "teaching-focused" contracts, both in the UK and elsewhere, continue to "count" as researchers? How does such a status impact not only the research of the scholars in question, but also their development as teachers? And what will this shift do to our wider understandings of the purpose and value of the academy itself, in the longer term?

As I began to develop the course materials, I came to see how such questions might in fact be reframed as an opportunity to think about the relationship between, on the one hand, the topic I'd spent so long researching (but not teaching)—marginality—and, on the other, my own (well-established if relatively "untheorized") teaching practice. Indeed, I had often pondered the fact during my years on fixed-term contracts that, while the neoliberalization of contemporary higher education has worked to intensify the long-running debate around the so-called "teaching/research divide" — and to produce a series of attendant (and equally persistent) calls for the importance of "research-led teaching" as a means of bridging such a gap — there has been comparatively little consideration given to the potential of the classroom itself to make an effective intervention. Is this because, as Tony Harland puts it, the very notion of "teaching-led research" is basically "counter-intuitive" and "difficult to realize"?5 Or is it more accurately understood as a reflection of the increasingly prevalent tendency, as analyzed by Buurma and Heffernan, to view university-level research and teaching as "vastly different, even incompatible, activities," all the while privileging the former over the latter in terms both of prestige and reward?6

The contemporary university is itself already fully dependent upon what Stefano Harney and Fred Moten describe as an "undercommons" of ruthlessly exploited and marginalized staff and students at almost every institutional level.7 As such, it seemed ever clearer to me, in designing a course on "marginality" from my newly "secure" (if still structurally ambiguous) position, that the classroom might necessarily be the most appropriate space in which to address such questions today. In forming this hypothesis, however, I was conscious of wishing not simply to reproduce by-now familiar gestures towards "non-hierarchical learning," "student-led pedagogy," the so-called "flipped classroom," and so on. Many such concepts seem now to have been appropriated and repackaged by the neoliberal apparatus, in somewhat dismaying fashion, from such powerfully counter-hegemonic works as Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed.8 Rather, I wanted to take this particular conjunction of personal and political contexts as an opportunity (if it were not already an outright political obligation!) to find ways to enact a genuinely radical politics of marginality in my teaching about it—or, to cite Spivak, I wanted as far as possible to "use [my]self [...] as a shuttle between the center [...] and the margin [...] and thus narrate a displacement" of the kinds of logics that underscore such binarized power dynamics in both the contemporary university and elsewhere.9

In the end, there were a number of strategies by which I attempted to do this — including, to take one example from early in the course, asking students directly about the kinds of challenges inherent in discussing "marginality" as part of a UK higher education context that has itself been shown systematically to "preserve" a range of entrenched socio-economic and political inequalities.10 The strategy that is chiefly under discussion, here, however, is my decision to include classes on questions of digital media and Artificial Intelligence (AI) that were — to me — almost entirely unfamiliar. This constituted a fairly substantial form of "pedagogical risk" on my part:11 originally trained as a scholar of twentieth-century literature, I also hold an (at best) shaky personal relationship with all kinds of so-called "modern technology," from computers and satnavs to smart phones and TikTok. At the same time, however, I had been increasingly aware that any research project (and thus any undergraduate course) on "marginality" would be incomplete without at least some consideration of the politics of so-called "techno-culture" — a point that only became clearer once students and academics everywhere began to discuss their concerns about the possible uses and implications of AI in late 2022 (GPT-3.5 was released just a couple of months before the new course was due to start).12 As such, I tried to put the knowledge about marginality that myself and the students would build — through readings by the likes of Christine Brooke-Rose, Jacques Derrida, Spivak, bell hooks, and M. NourbeSe Philip — into a dialogue with a technology and topic of undeniable relevance to us all, and yet about which none of us, myself very much included, could yet have much knowledge. Each of us in the classroom would, in this sense, be "shuttling between center and margin" in our different and no doubt unequally-constituted ways: we would all understand the means and conditions by which that opposition might be upheld, on the one hand, or "displaced," on the other.

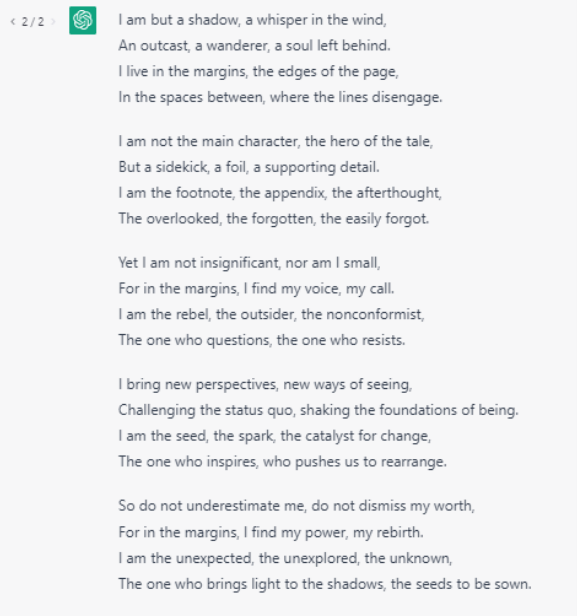

One activity I devised was as follows. Before the relevant class, we would all engage in our own individual "conversations" with GPT-3.5 about the topic of marginality, critically analyze its responses, and bring them along to the seminar for further discussion. The "conversation" with GPT-3.5 could take any form we wished: the idea was simply for us to think in "dialogue" with this new technology about the issues we'd been considering throughout the semester. And, while some students initially expressed reluctance, uncertainty, even anxiety about the prospect of engaging with such unfamiliar source material (both in technical and disciplinary terms), the activity led to a series of productive and insightful seminar discussions. We spoke, for example, about the ways in which GPT-3.5's attempts to explain "marginality" often seemed not only to reproduce certain arguments taken almost verbatim from the U.S. Black feminist tradition,13 but did so without either any acknowledgement of the labor of the thinkers involved, or indeed even a mention of the crucially racialized and gendered dynamics of those original arguments. Indeed, as one student — my co-author, Cyrus — pointed out, the "I" of GPT-3.5 seemed always to be implicitly North American, white, and informed by a rather anodyne (if apparently "naturalized") ideology of neoliberal individualism. And, as another student subsequently wondered, didn't this show how completely GPT's developer, OpenAI, is entangled in those predominantly white, patriarchal, and colonial forms of exploitation driven by Silicon Valley megaliths like Microsoft, Google, and Meta (whose PR machines, meanwhile, scramble to situate them at the very heart of decolonisation, EDI, and so on)?14

By the end of the class, we had begun to think about the ways in which AI technologies such as GPT-3.5, despite their apparently quite clear potential to restructure our very relationship to the world, can or indeed must be read as just another "text" before we will be able to grasp the wider ideological implications of either that "potential" or indeed that "restructuring." Like any other text, we had realized, such a technology produces its meanings in ways that are historically and politically implicated — ways that "center" certain perspectives while marginalizing others - and which therefore demand a careful, sophisticated, and sustained form of interpretation for their implications to be recognized in a comprehensive and responsible way. And, while such collective reflections were clearly just a start — an opening, the germ or seed of a viable critical approach — I believe they had emerged all the more powerfully (indeed all the more democratically) because the epistemological dynamics of the classroom itself had been shifted, or re-calibrated, somehow. In attempting to bring our shared knowledge about one topic (marginality) to bear on another about which we knew comparatively little (AI), we had all entered that dynamic space between center and margin — and, in doing so, we had effectively "'narrated a displacement" that seemed to have opened a door for further discussion, and further research, on the question of how such apparently "paradigmatic" technologies might nonetheless remain fully implicated in those dynamics of textuality and cultural politics with which we, as students of literature, were as familiar as anyone.

III. A student's perspective (CLM)

English Literature at the undergraduate level is at a junction. The United Kingdom is seeing fewer prospective students apply for English courses year-on-year. The National Association for the Teaching of English found that between 2012 and 2016 the number of English subjects taken at A-Level (i.e. at age 18) in the UK fell by 35%.15 The Fischer Family Trust's Education Datalab findings state that there has been a further 32.1% fall since 2016.16 As students move away from the subject, and Large Language Models (LLM) and other AI tools change how students participate in their degrees, understanding technology and embracing the digital humanities becomes increasingly imperative. The study of literature promotes critical thinking, empathy, skepticism, and sensitivity, a set of skills universally applicable regardless of a text's format. It encourages modes of thinking that make one more cognizant and wary of the apocalyptic late capitalism that many know dominates our economic and political landscape. The interdisciplinary approaches encouraged by the digital humanities can provide English Literature with the insights necessary to enable students and researchers alike to engage with technology critically, just as we already do with literature. Moreover, as such new technologies increasingly come to permeate every facet of our lives, a properly critical appreciation of their "textual" and socio-political dynamics will allow us to better understand the political landscape in which we are enclosed.

By encouraging students to approach digital technologies with the same critical perspective as would normally be applied to more "traditional" or "physical" texts, academics can help to shift the study of English Literature into the present and make for more nuanced readings in the future. Interdisciplinary collaboration will be vital, enabling an approach to the Humanities as a study of cultural practice in which individual departments can then provide a case study. Achieving effective cross-disciplinary collaboration will require departments to dismantle their often isolationist practices, a process in which the increased inclusion of students is imperative. Moreover, modernizing English Literature to include digital mediums will incentivize future students to engage with the subject again, as reading lists would need to become more properly transhistorical and intermedial instead of maintaining the more "traditional" (and anachronistically "one-dimensional") approach often taken to preparing course syllabi today. John Roache's course on "Culture and Marginality," which offered an interdisciplinary approach, was a putative microcosm of strategies that might be implemented more widely throughout the humanities. That course's methods effectively facilitated a collaborative and intermedial dialogue which should not be unique to that classroom.

The questions raised in classes regarding LLMs led me to my final essay for John's course. I argued that the effective marginalization of non-hegemonic positions by LLMs such as Bard and GPT-3.5 is a fundamental aspect of their construction. I came to this conclusion partly because of the collaborative nature of study in that classroom, where my ideas were developed in concert. The essay began from a contention that, in his article "A.I. Richards: Can Artificial Intelligence Appreciate Poetry?", the critic Jon Phelan fundamentally misunderstands the technical and political workings of LLMs.17 I determined that Phelan's critique fails to consider that AI models are, as Avon Huxor elucidates, "mediums".18 GPT-3.5 is a dataset containing countless individuals' appreciations, ideas, and feelings regarding literature. AI language models do not "create" interpretations or generate significance independently, as Phelan seems to suggest; instead, they "assemble" and "aggregate" certain forms of phrasing by using our interpretations and sentiments when discussing, for example in the case of my own essay, the possible meaning and significance of various forms of poetry.

During the semester, we did a relatively small amount of work on digital mediums; however, many of those in the class, including myself, had already been using AI to inform our readings, critiques, and essays. Traditional pedagogy often assumes the teacher's authority (the assumption Phelan wrongly makes of LLMs) but John acknowledges that he is an expert in neither AI language models nor digital textuality. Nevertheless, the classroom's collaborative format produced a form of expertise in itself because we understood that there was as much (if not more) knowledge amongst the students as there was at the front of the room. Clearly, like an LLM, the classroom is a medium. University is a space in which students and teachers continually learn together, and fostering a genuinely collaborative practice in this way improves the learning of all in the group. To some extent, then, the outcomes of a classroom, like the output of an LLM, might be seen as aggregations of the "data" we "train" each other on in that space.

Understanding how and why LLMs function in the ways that they do is fundamental to their practical use and for useful critical discourse about them. Challenging the ideological "center" from which they construct knowledge and reading them as texts in Literature classrooms will expose that center, allowing students to understand the political and social implications of their use. An LLM is first trained, and that training defines the definitionally hegemonic positions it centers. We as users then provide prompts which it responds to, selecting each "most likely" word consecutively until it concludes its reply. It is liable to disagree with you or end conversations that do not comply with the worldview it has been constructed by. The largest LLMs, Open AI's GPT and Google's Bard, are networks of North American Defaults, making the late-capitalist U.S. the "body" around which its hegemonic values orbit. This is despite the fact that LLMs will describe themselves as neutral parties, betraying an assumption of American supremacy. Recognizing the multi-authored nature of AI systems helps us understand that they reflect the biases in their training datasets, centering those biases and marginalizing differing perspectives. Essays, exam answers and classroom discussions can also be seen, in this sense, as "multi-authored"; humans, however, can retrain themselves and therefore address bias by referring to how and why we learnt that bias in the first place. As of now, this is not the case with any LLM.

As students bring digital knowledge and techniques that their teachers do not have to universities, the standard hierarchy of teacher and student changes. Currently, there is no tool available which can effectively discern whether a text has been written by a person or by an LLM; furthermore, as the LLMs progress, it will soon likely not be possible in any way to discern human from digital. With minor edits to a text, this is already the case. Plugins and secondary software already allow students to disguise evidence of LLM usage, and with further digital integration between software and platforms, this will only become easier.19 (Typically) younger students' fluency in digital media often gives them a profound understanding of the contemporary digital world that many older individuals lack. This means they are potentially able to study and produce work in a fraction of the time they traditionally would have. This in turn brings into question the role of marking, for while GPT-3.5 and 4 perform poorly on AP English Literature examinations,20 future versions will likely perform far better. An LLM able to write convincing and high-scoring essays in English Literature will soon be a reality, as it already is in the case of many other subjects — and where, therefore, students may conclude that it is actively disadvantageous not to use LLMs.

"English Literature" (as both a subject and a "canon" of works) already exists within thoroughly digitized landscapes. It is therefore crucial to integrate such landscapes more explicitly into the study of literature in universities in a manner that enables students to respond effectively to the impact of digital culture on literary production, reception, writing, performance, and interpretation. By incorporating digital tools, and trusting students, the study of literature can be genuinely "cutting-edge" and help to foster a more collaborative teacher-student relationship. We must invite the student into the classroom to learn and collaborate. Lifelong use means students already bring a deep understanding of online metaculture and exceptional digital literacy into classrooms. Until the study of literature integrates these forms of digital knowledge and pedagogical practice and becomes more thoroughly interdisciplinary in its guiding ideologies, this technological and epistemological disjunction will remain at the core of the subject.

Often-ignorant discussions about students using LLMs reveal the problem English studies has with its own atavistic hierarchies. The issue must be understood on the terms in which LLMs and classrooms actually exist, not as tradition or as an imagined future but as unavoidably (and becoming) symbiotic. Classrooms and LLMs are mediums; both negotiate inputs, draw on appropriate knowledge and output a collaborative response. Countless individuals indirectly collaborate on Open AI's GPT or Google's Bard just as they do in the university classroom. Each space offers immediacy of response and has the required prior training to respond compellingly, aggregating knowledge to produce dialogue. Therefore, mediating between training and learning is the medium, a middle space which moves us between the two. The journey is necessarily collaborative — and yet, genuine collaboration is still not standard in the English Literature classroom. In the near future, I would suggest, it must be.

IV. Conclusion (JR and CLM)

In an attempt to engage with some of the critical and political questions raised by questions of "marginality" in relation to recent developments in Artificial Intelligence, this essay has offered the "aggregated" perspective of a lecturer and student who have recently come into conjunction on a third-year undergraduate course in the UK. In this sense, it has attempted not only to articulate and analyze the potentially marginalizing effects of certain relatively novel (and increasingly popular) Large Language Models such as OpenAI's GPT, but also to enact the very "de-centralized" and collaborative approach to English literary studies for which its main argument has called.

There remain, it should be said, a number of important distinctions between the kinds of collaboration and "aggregation" that can be produced by the co-authored essay, the classroom, and the LLM. Each takes place within a particular social context and, as such, implies a particular set of (sociological, institutional, ideological) investments and relationalities. Furthermore, to the extent that the co-authored essay and classroom are still able (we hope!) to maintain a "critical" function — in contradistinction to the predominantly "reproductive" logic of LLMs — they also contain the potential, at least, to produce a range of dynamic and oppositional (if internally variegated and — in the case of the classroom — often unpredictable) responses to prevailing socio-economic and ideological conditions. (That potential also helps to distinguish such spaces, importantly, from the sorts of pre-formed and more or less empirically knowable "interpretive communities" hypothesized by Stanley Fish.21) In spite of these differences, however, we hope that by illuminating some connections between these particular forms, we have begun to demonstrate both the intellectual and political necessity of placing English Literature and Artificial Intelligence into a genuinely interdisciplinary — if also unavoidably complex and challenging — dialogue in the years to come.

Dr John Roache (he/him) is Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Literature at the University of Manchester. His research on marginality and literature discusses authors ranging from M. NourbeSe Philip to David Foster Wallace to Walter Benjamin, and has been published in journals including Textual Practice, Orbit, and symplokē. He is currently working on a book-length project entitled Rethinking marginality: global economies of text, capital, and power.

Cyrus Larcombe Moore, a queer poet with Essential Tremor, graduated from the University of Manchester in 2023 with a BA (Hons) in English Literature. He has won Foyle's Young Poet of the Year (2016), been longlisted for the National Poetry Prize (2017), and won the Chimera Projects Writers in the Field of Digital, Web-Based, and New Media Art award (2023). His debut collection, UnPunched, was published in 2021, followed by features in various publications, including by the National Tremor Foundation and Pilot Press. Cyrus is set to begin an MA in Poetry at Queen's University Belfast in autumn 2024.

References

- Rachel Sagner Buurma and Laura Heffernan, The Teaching Archive: A New History for Literary Study (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020).[⤒]

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, "Explanation and Culture: Marginalia" [1979], in The Spivak Reader: Selected Works of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, edited by Donna Landry and Gerald MacLean (London: Routledge, 1996), 35.[⤒]

- Buurma and Heffernan, 209-210.[⤒]

- The UK equivalent to a US tenure-track assistant professorship is a "permanent" lectureship — as distinct from casual or fixed-term (adjunct) teaching. Historically these lectureships have been oriented jointly around research and teaching, but lectureships focused on teaching have become more prevalent in the last decade thanks to various national shifts in higher education policy and funding.[⤒]

- Tony Harland, "Teaching to Enhance Research," Higher Education Research and Development 35, no. 3 (2016), 461.[⤒]

- Buurma and Heffernan, 1-24, 206-214.[⤒]

- Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (New York: Minor Compositions, 2013), 22-43.[⤒]

- See Henry A. Giroux, "Paulo Freire and the Politics of Postcolonialism," in Breaching the Colonial Contract: Anti-Colonialism in the US and Canada, edited by Arlo Kempf (Springer, 2009), 79-89.[⤒]

- Spivak, 35.[⤒]

- The initial response — a sustained, furtive silence — was one in which I felt every bit as implicated as the students. This collective "awkwardness" did, however, enable us to establish an initial sense in which our classroom discussions of marginality would necessarily be produced in relation to a range of structural and ideological limits, some of which are far more legible than others. For data on inequality in UK higher education, see the Institute for Fiscal Studies' report of September 2022 and the UK Parliament report of January 2023.[⤒]

- For a broader overview of the question of "risk" in contemporary teaching practices, see Patrick Howard, Charity Becker, Sean Wiebe et al., "Creativity and Pedagogical Innovation: Exploring Teachers' Experiences of Risk-Taking," Journal of Curriculum Studies 50, no. 6 (2018): 850-864.[⤒]

- For clarity: "GPT" refers to the Large Language Model created by OpenAI. The version discussed in this piece is GPT-3.5, which is currently free to access, whereas the technologically superior GPT-4 operates on a subscription model. There are also other LLMs available, such as Google's LaMDA, though GPT probably remains the most widely-discussed.[⤒]

- Most notably those made by bell hooks in a work such as Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (Boston,: South End Press, 1984).[⤒]

- Julia Carrie Wong, "Segregated Valley: The Ugly Truth about Google and Diversity in Tech," The Guardian, 7 August 2017.[⤒]

- Post-16 & HE Working Group "The Decline in Student Choice of A Level English: A NATE Position Paper," Teaching English (2022 [preprint]), 24. [⤒]

- "English Language and Literature: A-Level," Fischer Family Trust Education Data Lab, August 2022.[⤒]

- Jon Phelan, "A.I. Richards: Can Artificial Intelligence Appreciate Poetry," Philosophy and Literature 45, no. 1 (2021), 71-87.[⤒]

- Avon Huxor, "Artificial Intelligence: A Medium that Hides Its Nature," in Artificial Intelligence and Its Discontents, edited by Ariane Hanemaayer, (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022), 105, 111. [⤒]

- "Chat Plugins," Open AI, June 2023.[⤒]

- "GPT-4," Open AI, March 2023.[⤒]

- Stanley Fish, Is There a Text in This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980).[⤒]