Issue 9: Editing American Literature

"The women's presses keep the book in print until it finds its audience; Daughters, Inc. has gone back to press (sold out the first 3,000 copies) on every one of its novels; The Women's Press Collective and Diana Press have sold out the first printings of almost all their titles. . . . It is vital that we maintain control over our future, that we spend the energy of our imaginations and criticism building feminist institutions that women will gain from both in money and skills."

June Arnold, "Feminist Presses & Feminist Politics"

June Arnold, one of the principles of Daughters, Inc., a lesbian-feminist publisher that operated from 1972 until 1979, was serious about power. She understood the relationship between publishing and building political, social, and economic power: publishing books — and keeping them in print — was a way to gain "control over our future," and feminist institutions, like Daughters, Inc. and other lesbian-feminist publishers, were strategies for women to gain "money and skills." Arnold was a galvanizing force among lesbians and feminists during the 1970s. Since Trysh Travis's account of the Women in Print Movement and "their analysis of how gender and power shaped 'the little world of the book,'" multiple scholars have explicated this history though few have attended to editorial work done by these feminists.1 Jaime Harker situates its southern roots; Kristen Hogan maps feminist bookstores as an important site of antiracist thinking and activism in feminist and lesbian communities while Junko Onosaka considers the roles these bookstores played in making the stories of women's lives and experiences more visible and available to readers.2 Kathy Liddle develops the concept of "cultural interaction spaces" to describe feminist bookstores as spaces where women developed "identities as feminists and/or lesbians."3 Still other scholars use the print material from the movement to elaborate further the issues and concerns of lesbians; Cait McKinney, for examples, explores the "circle of lesbian indexers" who stepped up to make "critical choices about the tools" used and "the classifications schemes they assigned to 'lesbian experience.'"4 While these attentions are vital, examinations of editorial work by feminists in the Women in Print Movement have been modest, though the influence of lesbian-feminist editorial work on commercial publishing and reading communities today is enormous.

The publishing work of lesbian-feminists in the 1970s and 80s shares values, ideas, and affinities with the underground press movement of the 1960s. Donna Lloyd Ellis's early article "The Underground Press in America: 1955-1970," Abe Peck's Uncovering the Sixties, John McMillian's Smoking Typewriters, and Peter Richardson's A Bomb in Every Issue all capture the milieu of radicalism from the 1960s as it translated into publishing activities, even as all fail to treat the engagements and contributions of women in substantive ways.5 More recent scholarship by Martin Meeker, Roger Streitmatter, Jafari Allen, Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, and Darius Bost provides correctives, exploring feminist and queer print culture of this period.6 Benjamin Serby, for instance, describes how editors in the gay underground press "prioritized accessibility, transparency and participation" with the goal "not to produce newspapers, but committed radicals."7 Lesbian-feminist publishers wanted both: to produce books, chapbooks, magazines, newspapers, and other print materials and use these objects as tools to radicalize women to the ideas of lesbian-feminism. Yet editing and printed materials produced more than radical subjectivity; lesbian-feminists understood them as vital tools for world transformation.

Lesbian-feminists valued the labor of editing and publishing even as they critiqued its institutionalization. The Women in Print Movement arrived at a moment when editing emerged, in Susan L. Greenberg's history, as a "distinct professional role"8 and also as a function in the words of Abram Foley, "against the backdrop of a rapidly consolidating publishing industry, in the midst of 'the program era,' and, later on, in the context of a newly lauded creative economy that seeks to secure creative labor within the workings of capitalism."9 By the 1970s when the Women in Print Movement ignited, editing in commercial publishing was a skilled profession in a consolidated creative economy. Lesbian-feminists identified the primary function of editors as gatekeeping, and in Arnold's words, "intellectuals" edited in order to "put the finishing touches on patriarchal politics to make it sell."10 Arnold identified the emerging editor function as anathema to women's liberation. While Arnold skewered editorial operations in the "hard-cover of corporate America," the case studies below demonstrate that a different approach to editorial work was important to women working in lesbian-feminist presses.11

In her history of editing, Greenberg identifies three key aspects of editorial work: "selecting, shaping and linking."12 Peter Ginna similarly identifies these three elements naming them acquisition, text development, and publication.13 Though most lesbian-feminist presses were independent and operated with modest budgets, never working at the scale that Greenberg or Ginna describe, they used all three editorial functions in their work. Despite material limitations, lesbian-feminists published literary work with similar professional intentions as the "random houses" (June Arnold's term for "male-stream" presses).14 While all three editorial elements were important to lesbian-feminists, this article focuses on the publication, to use Ginna's word, or linking, as Greenberg describes it, component of editorial work to consider how the Women in Print Movement used publishing (linking) to proffer a vision of lesbian identity and visibility to a broader cultural context. In a similar register to how Foley's subjects use editing to "advance its own legible theories of textuality and meaning-making,"15 for example Foley examines how Nathaniel Mackey edits Hambone to develop his own poetics of "discrepant engagement," lesbian-feminists used publishing to create and promote lesbian culture.16 Across three case studies, this article explores how lesbian-feminists used book publishing to greenlight and assert editorial control over projects that centered lesbian voices and identities, to intervene in canon-making as it was being dominated by commercial New York publishers, and to demonstrate cultural commitments to lesbian books regardless of profitability in commercial markets. These case studies illuminate how lesbian-feminists understood the significance of building a cultural archive of books even as they learned that book publishing would not be an economically viable project to support women's livelihoods.

By providing three examples, I emphasize the variety of publishing in the women's liberation movement and return a sense of the excitement and polyvocality of the movement to the pages of history. The women of the Women in Print Movement are a disorderly and motley collection of publishers, activists, and writers. I yoke these women together to explain how their distinct editorial labors served lesbian-feminism collectively as a social and political movement. Ultimately, from these three case studies a more protean vision of the Women in Print Movement — and of lesbian-feminist editing — emerges.

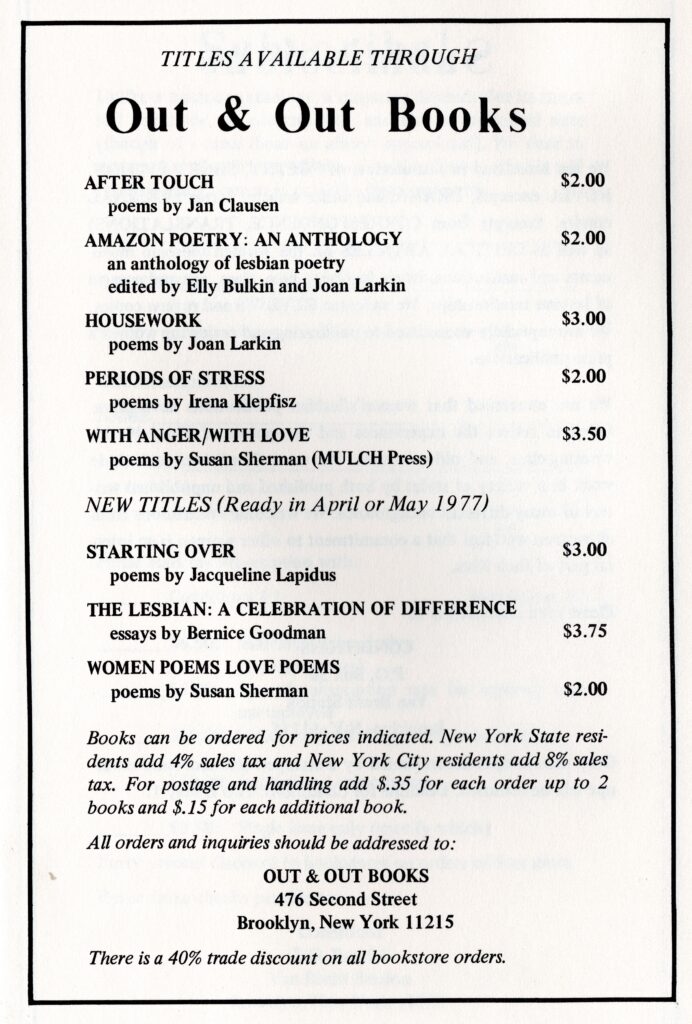

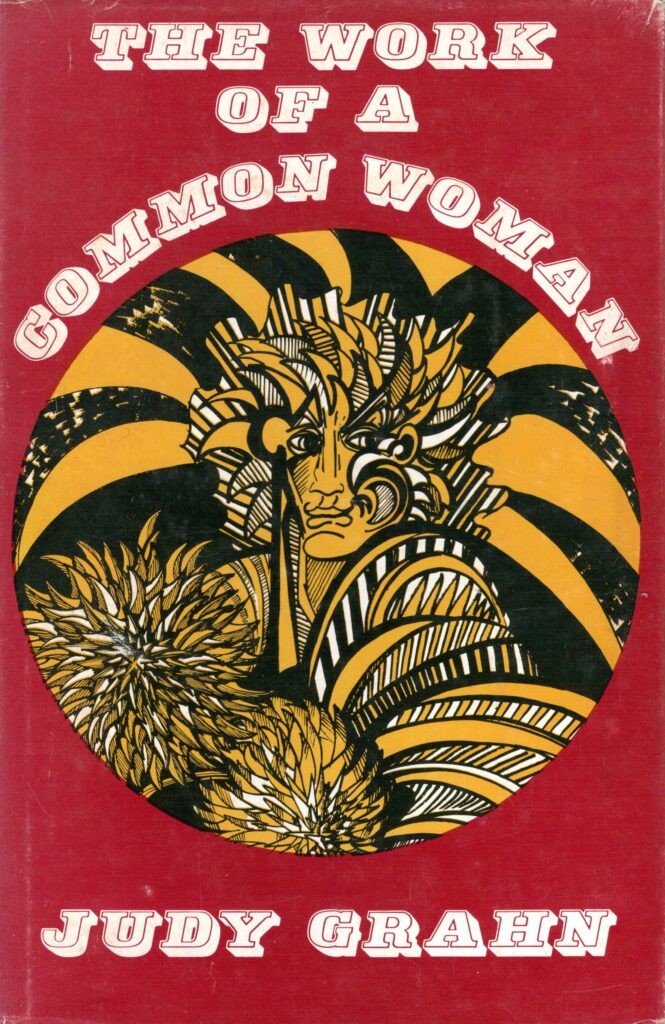

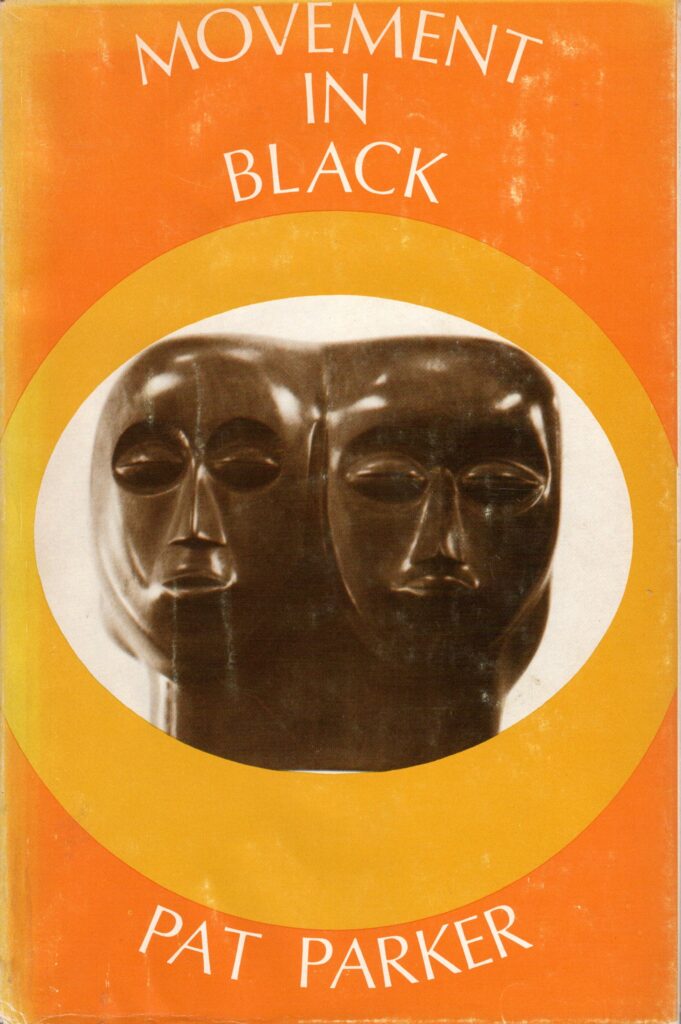

First, I consider a publishing collective that emerged from a poets' group called Seven Women Poets to become Out & Out Books, a coterie publisher of lesbian works. Among other important books, Out & Out Books published an influential collection of lesbian poetry, Amazon Poetry, that distilled an idea of lesbian poetry and provided a foundation for canonical anthology projects in subsequent decades including Persephone Press's Lesbian Poetry and Gay and Lesbian Poetry in Our Time, an anthology of gay and lesbian poetry that Joan Larkin edited with Carl Morse for a commercial press (St Martin's Press). Second, in the late 1970s, Diana Press published cloth editions of poetry collections by Pat Parker and Judy Grahn. These collections were the first hardcover books published by independent feminist presses. Diana Press invested in this project, using the cloth format to command power and respect and to influence canon formation. Although these editions ultimately were not successful in securing a place in the canon for Parker and Grahn, the spirit of these books and their entrance into the marketplace demonstrates the seriousness of lesbian-feminists in engaging cultural power through publishing. Finally, an editorial partnership between Joan Pinkvoss at Aunt Lute Books and Gloria Anzaldúa to publish Borderlands/La Frontera forged a new genre, new reading practices, and a best-selling book. Through her travels and readings, Anzaldúa trained readers, initially feminists and lesbians, to engage her rich hybrid text that combines poetry and prose, fiction and personal narrative. The combined labors of Aunt Lute Books and Anzaldúa on behalf of Borderlands made the new genre visible and also helped make the lives of lesbians visible and understandable. This case study also demonstrates the most important role of an editor: keeping a publishing house in business to keep vital work in print.

Lesbian-feminist publishers used the editor function to intervene in the broader culture on behalf of lesbian-feminist values. The women publishers in each of these stories worked to reach not only feminist and lesbian-feminist audiences but also broader audiences, worlds of people who might read and take up ideas from a group of women who, by and large, lived extremely marginal lives in the United States. These publishing activists wanted to transform literary fields for lesbian-feminist voices to be heard in meaningful ways. Not all their efforts brought success — and some success came only after long labor and time, but these stories illuminate some of the thinking and intentions of women involved in the Women in Print Movement. Not all the characters in these stories lived to see the effects of their work, and as with all canon-formation projects, the labors of editors and publishers often are overlooked or suppressed in later reckonings. These three case studies demonstrate how lesbian-feminists used editorial power, particularly in the final phase of the editorial process, publishing work with robust support and context to reach its audience. Through this labor, lesbian-feminists transformed the US publishing market to create a market for feminist, lesbian, and queer work; the effects of this work are still felt today.

"That's Not Vanity, That's Aggression:" A Story of Out & Out Books

A Brooklyn-based writing group called Seven Women Poets was the genesis for Out & Out Books, an early lesbian-feminist publisher that played a significant role in the Women in Print Movement. Joan Larkin, Jan Clausen, Irena Klepfisz, Alison Colbert, Sharon Thompson, Mary Patton, and Kathryn McHargue were the Seven Women Poets.17 Larkin describes the collective as "a very intense group" reflecting the "intensity of lesbian-feminism."18 The women of Seven Women Poets, who had done some readings together, imagined publishing a collection with work by all seven. This collection never materialized, but Out & Out Books published ten books, four chapbooks, and four broadsides.19 Collectively, the publishing output of Out & Out Books demonstrates a crucial value of lesbian-feminist publishing: women working together to make their writing visible to the lesbian-feminist community and through that process to a broader community of readers. These pragmatic goals align with the bold vision and intention of lesbian-feminists in the 1970s. In a profile of Daughters, Inc., a New York-based publishing house founded in 1973, Lois Gould explained in a New York Times article that the women of Daughters, Inc. "believe they are building the working models for the critical next step of feminism: full independence from the control and influence of "male-dominated" institutions—the new media, the health, education, and legal systems, the art, theatre and literary worlds, the banks."20 During these heady days of lesbian-feminism, nothing short of world transformation seemed possible to achieve equality for all people and the elimination of sexism, racism, homophobia, and other systems of oppression.

In a simple configuration, through publishing, lesbian-feminists sought to represent themselves and their lives in social worlds that excluded or demonized them. In the logics of the 1970s, heteronormativity rendered lesbians, and all creation that flowed from lesbians, as inferior, lacking formal and aesthetic value, and unworthy of distinction. Through their political and editorial work lesbian-feminists engaged keenly in the imaginative transformation from being represented by others to representing their own social worlds. They desired to reconstitute power in an egalitarian fashion and end the oppression of women, people of color, queer people, and other historically marginalized groups. Into this inchoate yet compelling vision of social transformation, Out & Out Books entered. The Seven Women Poets were all white and from a range of class, religious, and ethnic backgounds; in its work, Out & Out Books published key chapbooks by women of color, amplifying their voices. By narrating the work of Out & Out Books through the editorial lens of publishing, I present Out & Out Books as emblematic of an array of independent lesbian-operated feminist publishers of the 1970s and 1980s, including Granite Press, Lavender Press, Long Haul Press, Metis Press, Night Heron Press, and Violet Press, among many others.21 The Women in Print Movement developed through a range of independent publishers. Individual lesbian-feminists operated these publishing companies and presses, curating and promoting print materials that transformed what a lesbian was and could become.

The idea of publishing a poetry collection by the Seven Women Poets corresponded with a trip Larkin planned to San Francisco to visit Martha Shelley. Larkin and Shelley met in New York; Larkin had written a fan letter to Shelley after listening to her show, "Lesbian Nation," on WBAI, which ran in 1972 and 1973 during the heady early days of the women's liberation movement. Larkin recalls, "I loved her voice. I think it was the Yiddishkeit that came through. Here was a Jewish dyke who talked like Brooklyn and was very smart, and she had the message that I was passionate about at the time, you know, Dykes Ignite." At their first dinner together, Larkin was just coming out and Shelley "knew immediately what had to be done." A brief romance ensued that begat a friendship.22 Shelley "had been very moved by Judy Grahn's poetry" so she "moved out to California and joined the Women's Press Collective."23 When Larkin visited, she stayed in Shelley's home, shared with Judy Grahn, Wendy Cadden, Alice Molloy, and Carol Wilson, all members of the Women's Press Collective, the earliest lesbian-feminist publishing collective which published widely circulated books like Woman to Woman, a collection of poetry, Grahn's Edward the Dyke, and Pat Parker's Child of Myself.24 Larkin talked with the members of the Women's Press Collective as well as Alta of Shameless Hussy Press about the possibility of publishing the poetry collection. The West Coast publishers were not able to commit to the project, but Larkin told me "it was inspiring to connect with both Alta and with Judy and to see the beautiful books that the Women's Press Collective were doing."25 In response to Larkin's inquiry, Alta prophetically told Larkin "to publish it yourself." She returned to Brooklyn with the idea of starting a press.26

Although the collection that Seven Women Poets initially envisioned was never published, Larkin, Bulkin, Clausen, and Klepfisz started Out & Out Books. Clausen, in her memoir Apples and Oranges, describes it as "cooperative self-publishing" through which they "would issue poetry books under a common imprint" to "give each writer or editor control of her own project while averting the stigma of vanity publication" and that they "would share distribution and publicity efforts."27 This narrative, published more than twenty years later, flattens the heat and passion of lesbian-feminist publishing (in fact dozens if not hundreds of lesbian-feminists were starting their own presses to publish work), reducing the impulse to individual control and the avoidance of stigma. For lesbian-feminists, control in the publishing process meant being able to authorize and oversee the publication of explicitly lesbian poetry. Vanity publishing was, in fact, one of the few reliable ways for lesbian literature to reach readers because of the way that lesbians were stigmatized culturally, socially, and politically. A generation earlier, Jeanette Howard Foster self-published her influential book, Sex-Variant Women in Literature, after numerous mainstream publishers declined it.28 Judy Grahn dismissed Larkin's anxieties about the stigma of self-publishing during her trip to San Francisco. When asked if she was concerned if someone would view the Women's Press Collective as vanity publishing, Grahn's retort was, "Hell, that's not vanity, that's aggression."29 For out literary lesbians in the 1970s, publication, the final phase of editorial work was a way to enter and change the world.

The first project published by Out & Out Books was a collection of lesbian poetry, Amazon Poetry. Larkin and Bulkin compiled and edited the anthology throughout 1974 and 1975. Amazon Poetry was a watershed collection articulating the existence of "lesbian poetry" as a category and as an aesthetic. The formal editorial and curatorial work that Larkin and Bulkin did in this collection echoed for the next two decades in lesbian-feminist literary worlds. In addition to Amazon Poetry, Out & Out Books published three other poetry collections in 1975: Jan Clausen's After Touch, Larkin's Housework, and Klepfisz's Periods of Stress.30 All three collections were written by members of the initial collective. These books launched each of the authors into more public roles in the burgeoning lesbian-feminist movement.

After its initial publishing activities of 1975, Out & Out Books continued publishing a series of books, chapbooks, and monographs over the next five years. All Out & Out Books projects emerged from vibrant social and political relationships forged through lesbian liberation formations in New York during the late 1970s. Larkin recalls that while the press didn't generate profit, she didn't heavily subsidize the publishing activities either because sales were sufficient to cover production costs (though not enough to pay for writers' and publishers' labor).31 This business model, where revenue from previous projects covered the material costs but not labor of future projects, is characteristic of independent lesbian-feminist publishers from the period. While women wanted to find ways to support themselves through publishing, it was not possible at the scale that Out & Out Books and other publishers operated during the time period. Larkin and her cadre at Out & Out Books worked other jobs to support themselves.

In 1977, Out & Out Books published two more books and two pamphlets. The books, Bernice Goodman's The Lesbian: A Celebration of Difference and Jacqueline Lapidus's Starting Over: Poetry, both came to Out & Out Books through personal relationships. Goodman was Larkin's therapist and well-known as a "guru in creating lesbian communities" in New York and Lapidus was a friend of Larkin's.32 These social connections are significant. Lesbian-feminists networked intensively during this period, making connections through friendship, correspondence, reading, and social and political gatherings. Friendship networks provided a source of authors and readers for independent lesbian-feminist presses.

The two pamphlets demonstrate how lesbian-feminist publishers amplified lesbian critiques of culture among influential lesbian reading communities, particularly in New York City. The first pamphlet was a speech by Adrienne Rich titled, "The Meaning of Our Love for Women is What We Have Constantly to Expand."33 The occasion of Rich's speech was Gay Pride on June 26, 1977. Rich writes that "the summer of 1977 was a summer of militant, media-scrutinized 'Gay Pride' marches, responding to the anti-homosexual campaign whose media symbol was a woman, Anita Bryant." This confluence of Gay Pride and the vilification of a woman, Bryant, resulted in lesbian-feminists feeling "torn and alienated." Rich says, "Our understanding of the meaning of Anita Bryant, and the meaning of woman-identification, was of necessity more complex (than the meaning of the gay male community.)" Thus, a small group of women chose "to separate from the Gay Pride demonstration in Central Park's Sheep Meadow and hold our own rally."34 Rich addressed this rally. Out & Out Books typeset and printed Rich's speech as the "first in a series of pamphlets on lesbian-feminism."35 This pamphlet was so successful that in 1979, Out & Out Books produced a second printing of the pamphlet, after W. W. Norton published Rich's collection On Lies, Secrets, and Silence, which also contained the essay. The genesis of this essay and its subsequent circulation, amplified by the Out & Out Books pamphlet, exemplifies how lesbian-feminist publishing overlapped with activism and embedded its values. Lesbian-feminist publishers selected, curated, and amplified activist voices, and on occasion, they magnified voices in commercial publishing to ensure they reached lesbians.

The second pamphlet that Out & Out Books published in 1977 was Barbara Smith's influential essay, "Toward a Black Feminist Criticism," originally published in Conditions 2 (1977). Bulkin, Clausen, and Klepfisz were all founders and editors of Conditions.36 In "Toward a Black Feminist Criticism," Smith identifies key elements for Black feminist approaches to literary work by Black women, including, notably, a reading of Morrison's Sula from the perspective of the erotic intimacy between Nel and Sula. By combining Rich's essay with Smith's in the pamphlet series, Out & Out Books conveyed the significance of publishing work by white women and African-American women together and affirmed that multiple iterations of published work could reach new audiences and support both writers and readers.

Joan Larkin emerged as the principal editor and publisher of Out & Out Books and other women joined her. Larkin's lover, Ellen Shapiro, had a background in typography and book design. She oversaw design and production for all the books produced by Out & Out Books beginning in 1977.37 Beth Hodges and Terry Antonicelli also worked with the press briefly. In 1980, Larkin hired Felice Newman and Frédérique Delacoste, who were lovers at the time, to help with the press. Newman and Delacoste worked briefly with Larkin then began the publishing company Cleis Press, an influential feminist press during the 1980s and 1990s. Publishing was an activity for lesbian-feminists to support their writing and intellectual lives, to communicate with other women in the movement, and to mobilize networks of friends and lovers in shared projects and mutual support.

Over the next three years, Out & Out Books maintained an impressive publishing pace reflecting the vibrancy of lesbian-feminism during this period. Out & Out Books published work by Olga Broumas, Melanie Kaye, June Jordan, Beverly Tanenhaus, Blanche Wiesen Cook, Joanna Russ, Marilyn Hacker, and others. Each of these women were building literary careers and had personal connections to Larkin. Broumas won the Yale Younger Poets Prize in 1977; Russ was well known for her 1975 popular science fiction novel, The Female Man. Hacker and Russ were in an amorous relationship. All would continue to write and publish influential work over the next decade.

The work of Out & Out Books demonstrates the attentions and significance of writing and publishing within lesbian-feminist communities as well as their overlapping modes of cultural communication: speeches, poems, articles, and stories all provided fodder for the cultural reimagining of the world in lesbian-feminism, and distributing these ideas through a variety of print projects was a vibrant editorial mission for independent lesbian-feminist publishers like Out & Out Books. Out & Out Books operated as a space for community building and networking both through the production of the books themselves and also through the distribution of the books at poetry readings and other events. These were books imagined, edited, and published by lesbian-feminist writers for lesbian-feminist readers. Through Out & Out Books, a wide range of New York-based writers engaged in some aspect of publishing — writing, designing, printing, and selling books of interest to lesbians and feminists. For Out & Out Books, relationships drove publishing and conflicts inspired other publishing projects. While Larkin described the publishing as "disorganized" and "relationship-based," the caliber of authors published by the press and the quality of the work published continues to appear, in retrospect, extraordinary.38

By 1980, Larkin wanted to turn her attention elsewhere. She reflected, "I had my own road that I had to travel to sobriety ... and part of the letting go of Out & Out Books [was] distancing myself for a very long time from some of the people that I had done all of the work with."39 About her years as publisher of Out & Out Books, Larkin remembers both "a lot of anger and intense conflict as well as a lot of just amazing connection and blazing."40 Shapiro recalls, "There was very little money involved and lots of time, and, after a while, it felt like it was time to move on to other stuff."41 Shapiro reflects that Out & Out Books "was a really good mirror on the times" because "it brought the words of interesting, important writers" to readers, cheaply. She says, "there was nothing flashy about the products. It was really about trying to disseminate them in ways that lots of people could read them."42 Like many other independent lesbian-feminist publishers of the 1970s and 1980s, Out & Out Books ended so that the women involved could turn their attention to other projects.

Lesbian-feminists found themselves by and large outside of communities of literary gatekeepers and unable to access literary power structures with work that included openly lesbian content. Primarily because of this lack of access to formal publishing networks, a "do-it-yourself" ethic shaped lesbian-feminist publishing during the 1970s. This response to exclusion, however, should not be understood as eschewing editorial attention and power. Lesbian-feminists created their own literary communities with vibrant periodicals and independent publishers. They developed their own editorial strategies and recognized the significance of editorial work, particularly selecting and curating poems and literary objects for readers. The members of the Seven Women Poets collective helped one another shape individual poems and consider the selection and arc of poems for their books. This collaborative editorial work shaped strong collections by Larkin, Clausen, and Klepfisz and each built on those debut collections to pursue other creative book projects over long careers.43 Out & Out Books, primarily Joan Larkin, selected work for a variety of publishing projects. While Larkin describes the work she published as coming to her through friendships and community networks, the significance of the list of published writers in Out & Out Books suggests careful curation of work that over time has become profoundly influential and, in many cases, iconic. While Larkin credits her social life with creating the connections and networks for the curatorial work, her labor as an editor combined with her interpersonal sensibilities imbued Out & Out Books with a powerful and influential catalog. Poets and writers who would transform lesbian literary communities found editorial care and a receptive audience through Out & Out Books.

Larkin herself became a significant editorial voice shaping and illuminating lesbian poetry and then gay and lesbian poetry through anthology projects that influenced canon formation. After Out & Out Books shuttered, Larkin and Bulkin expanded Amazon Poetry into another widely circulated anthology, Lesbian Poetry, published in 1981 by the independent feminist publisher, Persephone Press. The publications of both Amazon Poetry and Lesbian Poetry corresponded with a variety of public readings by poets included in the collection and other community-based celebrations. Larkin's editorial expertise was recognized in commercial publishing in the late 1980s when she and Carl Morse published another ground-breaking anthology Gay and Lesbian Poetry in Our Time (1988) with St. Martin's Press. As Rich described expanding "the meaning of our love for women," Larkin and Out & Out Books pressed that expansive love for the work of women onto paper as broadsides, pages of books and chapbooks, into an enduring editorial legacy.

"Committed to Putting Power into the Hands of Women": Diana Press and Clothbound Editions

When did mainstream literary culture become aware of the feminist revolution at hand? Perhaps in 1974 when three National Book Award poetry finalists, Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, and Alice Walker, banded together to accept the award collectively "in the name of all the women whose voices have gone and still go unheard in a patriarchal world, and in the name of those who, like us, have been tolerated as token women in this culture, often at great cost and in great pain."44 Rich and Lorde delivered the speech at the awards ceremony in Alice Tully Hall, alerting the gathered luminaries that they spoke to obliterate patriarchy. Perhaps mainstream literary communities smelled the flames of revolution when Stanley Kunitz selected Olga Broumas and her lesbo-erotic poems as the winner of the Yale Younger Poets Prize in 1977. Or perhaps it happened at some other flashpoint during the 1970s; there are many. Feminist and lesbian-feminist poetry was in the air.

In the mid-1970s, vibrant lesbian-feminist communities were in full motion around the United States with various points of energy and activity in cities as diverse as New York, San Francisco, Iowa City, Chicago, Gainesville, and Northampton.45 In each of these communities, networks of poets and poetry flourished. Poetry offered a multitude of voices on lesbian-feminism grappling with a range of issues important to the movement: identities, class, love, sex, desire, race, interpersonal relationships, and politics, among other topics. Lesbian-feminists celebrated the polyphonic voices emerging from the movement as the broader culture searched for a way to understand and consolidate these voices.

The typical response to subcultural activity, as Dick Hebdige explains, is to incorporate its revolutionary zeal into mainstream culture, to defang, depoliticize, defuse it?. Subculture blunting happens in two ways: "through commodities and through ideologies."46 In the mid-1970s, while mainstream literary cultures searched for ways to incorporate lesbian-feminist subculture, lesbian-feminist publishing activists like the editors at Diana Press sought ways to intervene and preserve their radical imaginings.47

Lesbian-feminists working at Diana Press on the West Coast sensed that the "random houses" would try to distill and subordinate the vibrancy of lesbian-feminist subculture into a consumable cultural morsel by making stars of Adrienne Rich and Audre Lorde. Analyzing the situation, Diana Press developed a strategy to contest potential exclusions that might follow from the emerging canonization of Rich and Lorde: publishing hardcover cloth editions of Pat Parker's iconic Movement in Black and Judy Grahn's The Work of a Common Woman.

It was a bold move. Most independent feminist presses published exclusively paperback editions. The lower cost for both publishers and consumers aligned with feminist, anti-capitalist sentiments. For publishers, paperback editions made it easier for women to initiate publishing companies with a smaller capital investment. But although the initial investment was smaller, recouping the investment was more difficult given the smaller margins on paperback editions, although none of the independent lesbian-feminist presses centered these types of financially savvy analyses in their work. For book buyers, paperback editions reflected the reality that women — and lesbians — often had less disposable income for purchasing books. Paperback books, however, were rarely reviewed in mainstream media; editors reserved their attention for cloth editions. Positive review attention elicited great cultural capital among literary tastemakers, often translating to inclusion as teaching texts and eventually canon formation. Paul Lauter explores how canons "are deeply shaped by . . . the material conditions under which writing is produced"48 and explains how the literary canon is "a means by which culture validates social power."49 The women of Diana Press were both aware of the scholarly conversations about canon formation and the material consequences of publishing only paperback editions. Given their higher production cost, cloth editions were primarily the realm of commercial publishers until Diana Press staked a claim to the canon for Parker and Grahn.

Diana Press, founded in Baltimore, Maryland in 1972, operated as both a book publisher and as a commercial printing business, doing work for hire to support book publishing work. In 1975, founders Coletta Reid and Casey Czarnik moved Diana to the San Francisco Bay area, and the move enabled Diana Press to save money on rent and gave Reid and Czarnik the opportunity to work with allies and comrades at the Women's Press Collective, including Pat Parker and Judy Grahn. Like other feminist publishers, Diana Press described their mission with revolutionary fervor.50 In a 1974 press release after a fire at their office building in Baltimore, they wrote, "Diana Press hopes to become part of a feminist publishing renaissance that makes the commercial houses obsolete."51 The vision was both to publish feminist books by feminist writers and to challenge the commercial, patriarchal establishment. Diana Press did just that from 1972 until 1979, publishing nearly two dozen transformative books by an array of feminist writers, including Rita Mae Brown, Barbara Grier, Charlotte Bunch, and Nancy Myron.52 While Diana Press achieved some extraordinary success, the 1978 cloth editions of Parker and Grahn were orphaned when the press collapsed in 1979. The editions did not secure a place in the canon for the authors as envisioned, partially because sales, marketing, and publicity operations ceased shortly after their publication.

Grahn and Parker were beloved poets in the San Francisco Bay area and because of a nation-wide reading tour they had done a few years earlier, they were also well-known in lesbian-feminist communities around the country. Their poetry appeared in multiple feminist journals, newspapers, and other print publications, and the work of these two friends exemplified the poetry that women hungered for in the 1970s. Earlier editions of books by Grahn and Parker had been bestsellers for the Women's Press Collective. Grahn and Parker also echoed Rich and Lorde in their work, their activism, and their community engagements. These poets all knew one another and saw each other as comrades in the work of poetry and revolution. Yet, all were aware of the divisive external forces of broader public recognition and canonization, and the women of Diana Press worried that the literary and publishing powers in New York would privilege the work of Rich and Lorde over Parker and Grahn given their proximity.53 The cloth editions were a strategy to address that concern. In true feminist fashion, Diana Press enlisted Rich and Lorde to write introductions for the new editions, projecting Rich, Grahn, Lorde, and Parker as equals and not rivals, demonstrating a vision of abundant poetic voices within lesbian-feminism. A sense of rivalry with New York power structures may have influenced the decision to publish these volumes, but the publisher and the poets saw each other as peers.54

While the aspirations for these cloth editions were both lofty and reasonable, Diana Press did not continue its operations long enough to realize them. A series of financial and other challenges beset the company and the business had to wind down. As a result, though the cloth editions of The Work of a Common Woman and Movement in Black appear to have sold out, neither took flight. The poems, collections, and poets achieved extraordinary staying power within lesbian-feminist communities and beyond; multiple editions of both volumes were subsequently released by independent feminist presses and the poems remain in print today. However, the volumes failed to parlay Parker and Grahn's successes into major book deals and long-term relationships with commercial publishing houses, nor did the volumes secure reviews and critical attention in mainstream national media outlets.55

Why did this canonization project fail? The shuttering of Diana Press ended the support and publicity for the two books, short-circuiting an envisioned long campaign of promoting and championing the books and the authors' entire catalogues. The road to canonization is slippery and, of course, extends beyond a single edition of a book or a single publisher. Though Parker and Grahn were fierce promoters of their work and had devoted readers, their work was always published by independent and feminist presses whose precarity and instability sadly limited the continuous availability of their books. In addition, Lorde's and Rich's moves to W. W. Norton, a key publisher shaping contemporary canons in the Norton anthologies, combined with a mainstream editorial tendency to include and privilege singular representations of diverse movements, strengthened the standing of Lorde and Rich in the public eye and eclipsed Parker and Grahn.

The story of these two clothbound books demonstrates how keenly attuned to broader cultural trends lesbian-feminist publishers were — and how they sought to transform the broader culture. Activists at Diana Press imagined their clothbound editions of Grahn and Parker intervening in cultural conversations and situating these two poets within a broader mainstream culture. Ultimately, their intention was not simply to secure a place for Parker and Grahn alongside Rich and Lorde, but to challenge the logic of scarcity and the selection of a small group of people representing movement work. They sought to elevate not their preferred soloists, but a symphony of voices to represent lesbian-feminism (a notion supported by the large number of anthologies and collections published by Diana Press) and thought that Parker and Grahn must be among those voices. While Diana Press's cloth editions were ultimately unsuccessful, their efforts exemplify the lesbian-feminist movement's desire to create culture for both lesbian-feminists and for the broader US literary culture, a vital aspiration that deserves more understanding in contemporary appraisals of publishing history. Lesbian-feminists edited not only for their communities of care and concern, for the women they knew who wrote and bought their books, but also to change the broader literary community and the methods and movements of canonization.

"This Wonderful Mix of Form:" Aunt Lute and Borderlands

While Diana Press was shuttering its operations, another collaboration was beginning to alter feminist publishing and contemporary understandings of literary genres. Collaboration was a part of the zeitgeist of lesbian-feminism and its publishing endeavors. In 1981, Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa co-edited and published This Bridge Called My Back with independent feminist publisher Persephone Press.56 Near the end of the book's development, Anzaldúa began treatment for uterine cancer for which she ultimately had a hysterectomy. As a result, Moraga notes in later writing about the collaboration, Anzaldúa "yielded much of the book's direction to me and there had been little debate between us."57 A few years after the book's publication, Anzaldúa told Moraga that "the book did not reflect her vision."58 While This Bridge may have diverged from Anzaldúa's vision, it spoke powerfully to generations of feminists, becoming one of the best-selling books of the women's liberation movement and continues its work in a fifth edition for its fortieth anniversary. Fortunately, Anzaldúa's work did not end with This Bridge, and her most influential works were yet to come. In the mid-1980s, Anzaldúa completed another book, one critics now regard as her masterwork, Borderlands / La Frontera. She published this book with white lesbian-feminist Joan Pinkvoss, founder of the independent press Aunt Lute Books.

Anzaldúa scholarship has discussed the collaboration between Pinkvoss and Anzaldúa extensively, particularly in introductions to different editions of the book and in M. Bałut Fondakowski's recent chapter.59 Fondakowski interviewed Pinkvoss when she received the San Francisco Arts Commission's Artist Legacy Award for her service to the community over decades. Borderlands is "one of Aunt Lute's most in demand books, though it took years for the book to find its readership and place in the canon."60 Vivancos-Pérez provides a chronology about the genesis of Borderlands and Anzaldúa's "process of writing it."61 My narration of this history emphasizes three ideas. First, within the Women in Print movement, collaboration was crucial and valued. Between Pinkvoss and Anzaldúa, the collaboration was not only between editor and author but also between publisher and author; the economics of publishing, which Pinkvoss was learning as she acquired, edited, and published the book, shaped it. Second, collaborations between white women like Pinkvoss and women of color like Anzaldúa were a part of both the Women in Print Movement and broader feminist activism in the 1970s and 1980s. Third, a crucial and underrated role of editor, which Pinkvoss exemplifies, is keeping work in print. Conceptually, these three aspects of this editorial story highlight contributions of lesbian-feminism to editing studies.

Pinkvoss first heard Anzaldúa read from her work in Iowa City. Pinkvoss trained as a writer in the prestigious MFA program at the University of Iowa in the late 1960s. While living in Iowa City, she connected with a vibrant feminist community; Iowa City was the birthplace of a number of feminist projects including the Iowa City Women's Press, Common Lives / Lesbian Lives, and the newspaper, Ain't I a Woman?. Anzaldúa traveled from her home in the San Francisco Bay Area to visit Iowa City — and its active lesbian-feminist community — for a reading. After hearing Anzaldúa, Pinkvoss approached her and asked if she had plans to publish; Anzaldúa said no. Pinkvoss told her that Aunt Lute Books and Spinsters Ink, two independent feminist publishers, were merging and that she was moving to the Bay Area to work on the newly named press, Spinsters/Aunt Lute. Pinkvoss told Anzaldúa that she was happy to talk to her more about publishing. A conversation began.62

Pinkvoss had published a handful of books as Aunt Lute Books when she arrived in San Francisco, but she was still working through an economic model and identity for its publishing work.63 Through the merger with Spinsters Ink and an examination of its revenue, Pinkvoss realized that she "couldn't really sell a book of poetry."64 While many lesbian-feminist publishers published poetry collections that sold enough to support the next book (the model that Out & Out Books used), poetry collections do not provide enough revenue to support a publishing operation that pays for editors and publicists' time. Poetry publishing continues to be either philanthropically supported or supported as a division within commercial publishing. Economically, Pinkvoss realized, poetry would not provide the support Spinsters/Aunt Lute needed, and as a publisher, Pinkvoss was looking for books that would make an impact; she worried that poetry books "wouldn't really be that big and wouldn't really carry the message."65

The first manuscript Anzaldúa gave to Pinkvoss was only poetry. Pinkvoss asked Anzaldúa, do you have "any stories?" Anzaldúa told her, "Well I have these few essays that I've kind of been working on."66 Today, of course, the essays are what most people know as Borderlands / La Frontera. Initially, in Anzaldúa's mind it was a poetry manuscript. It became a hybrid book because of the economic necessities of publishing that Pinkvos was coming to understand while working with Anzaldúa.

Pinkvoss describes the project as "essays, which are poetical, and the poetry which is narrative, and this wonderful mix of form that Gloria did. And we worked a lot together on the theory part . . . especially on theorizing the New Mestiza." Pinkvoss remembers, "she was very clear she wanted to go someplace beyond This Bridge Called My Back in terms of using her own life as a metaphor about where women needed to go to build, [where] women and lesbians needed to go to build a new culture." From Anzaldúa's vision, the project developed. Pinkvoss remembers that Anzaldúa was "amazingly off the charts creative" and that she saw firsthand the way that Anzaldúa worked with "visual conceptualization and personification" and worked with "animal involvement in [the creation of feminist and queer] theory."67 These elements became central to Borderlands.

The challenge that Pinkvoss encountered with the project was helping Anzaldúa "let go of this material." Pinkvoss remembers, "She just couldn't let go." Thus, Pinkvoss's editorial contribution in part involved "getting her to see the end of it and completing it as much as she could."68 This labor of completion, a demarcation of the end of a manuscript and the movement of those words and ideas into the finished pages of a book, is vital editing labor and labor that lesbian-feminist editors provided. For many lesbian-feminist publishers, their existence in the world and their interest in writers' manuscripts drove women to complete their projects. In this case, Pinkvoss and Anzaldúa had an active dialogue about the process of completion and letting go. Through this process, Anzaldúa completed Borderlands and released the manuscript to Pinkvoss for Aunt Lute to publish it.

The shared editorial process is captured in part in Anzaldúa's acknowledgments in Borderlands. About Pinkvoss, she writes, "my editor and publisher, midwife extraordinaire, whose understanding, caring, and balanced mixture of gentle prodding and pressure not only helped me bring this 'baby' to her, but helped to create it." Anzaldúa uses the conventional metaphor of midwifery to describe her relationship with Pinkvoss but also gestures to the idea that their relationship is not only facilitative but also collaborative, they were engaged together in the creation of the book. She concluded the paragraph with "these images and words are for you."69 Most authors thank their editor in the acknowledgments, but this statement confirms the shared editorial experience that Pinkvoss described.

During its first three years, Borderlands sold very few copies. Pinkvoss remembers, "People had no idea what it was, it was so strange." The blending of genres, poetry, personal essays, and feminist theory into a single text was unfamiliar to readers, even though feminist writers like Audre Lorde, Minnie Bruce Pratt, Mab Segrest, and others were experimenting with similar challenges to genre.70 After Pinkvoss walked the book into an editor's New York office, the January 1988 issue of Library Journal named Borderlands one of their top fifty books for the year, describing it as "a rich and moving personal account" of Anzaldúa's "roots in folk Catholicism, Indian religious symbolism, and lesbian feminism."71 Aunt Lute sold some copies to libraries. Bookstores in the Bay area carried it, but Borderlands was, at the beginning, a quiet book.

Then Anzaldúa started giving more lectures. She traveled and connected with audiences, talking about the book. Pinkvoss remembers Anzaldúa saying to her, "Joan, I don't understand, people are starting to really get the book, and they're buying it." Pinkvoss responded, "That's because you're teaching them how to read it. [It's] your talking about these things in public that's allowing people to better understand how to approach the work."72 This experience and understanding of the book was transformative. It both sparked sales of the book and helped Anzaldúa secure a teaching position at UC Santa Cruz. The combination of these two conditions brought more economic security to Anzaldúa.

Anzaldúa's travels and talks about Borderlands and her teaching became the seed for Haciendo Caras, the compiled reader the Anzaldúa created with Pinkvoss again as her editor and publisher. Pinkvoss recalls hearing from teachers in the field through her travels as a book publisher that they wanted "a compendium of many voices of women of color"; simultaneously, Anzaldúa realized how hard it was to teach because she "didn't have enough published resources and so she was accumulating her own work from essays and other unpublished materials." Pinkvoss proposed to her, "why don't we just make this anthology of that work that you're doing." A simple idea but an arduous process for both. Haciendo Caras eventually came out in 1990 and was another best-selling book for Aunt Lute and Anzaldúa. Haciendo Caras exemplifies another form of collaboration crucial to the Women in Print movement. Anthologies embodied the polyvocality that lesbian-feminists imagined for their movement. Joan Larkin distilled the idea of lesbian poetry through her editorial work with Amazon Poetry; Anzaldúa both through This Bridge and Haciendo Caras assembled multiple voices to synthesize a vision of women of color feminism. She collaborated with authors and Pinkvoss as her editor to create the anthology.

In Haciendo Caras, Anzaldúa describes Pinkvoss as "publisher, editor and kindred spirit whose unrelenting faith in my work sustained me through all the various stages, crises and crazies I went through constructing this book."73 Anzaldúa's brief acknowledgement of Pinkvoss's significance as an editor and publisher is a gesture to the many labors of Pinkvoss in particular and feminist publishers in general, from creating and sustaining publishing companies to supporting authors in completing their books and then providing support for the promotion of books, including even personally delivering books to reviewers. Feminist editors and publishers fill a vital role in creating and nurturing authors and broadly promoting feminist literary work.

Pinkvoss was able to give the time and attention to Anzaldúa's creative projects because of the existence of Aunt Lute Books. The presence of feminist and lesbian-feminist publishers supports the labor of lesbian-feminist editors, giving them time and space to both edit books, but also as the case of Haciendo Caras demonstrates to help imagine new, transformative books. Lesbian-feminist publishers and editors not only publish books for eager readers but they also help create them; they, to use Anzaldúa's word, midwife lesbian-feminist books into the world. Pinkvoss worked as a collaborator with Anzaldúa in the making of two of her influential books. Pinkvoss, and feminist publisher Aunt Lute Books, helped to incubate and deliver two influential books into the world.

This editorial partnership between Anzaldúa and Pinkvoss is notable. As an extraordinary editor, Pinkvoss works behind the scenes with little attention to her labors; in fact, she prefers to focus attention on books and their authors, a time-honored tradition in trade publishing. Yet, highlighting the relationship demonstrates the significance of both independent publishers as well as editors. Commercial publishing may be able to produce materially books by feminists, lesbians, queer authors, and BIPOC people with the many ways that those identities overlap, but this story demonstrates the significance of the incubation of these books.

The racial dimension of this editor-author relationship is also important. It demonstrates a reality of many strands of feminism from the Women's Liberation Movement in which white women and women of color worked collaboratively to address intersecting oppressions of gender, race, class, and sexual orientation. In narrating this editorial collaboration, I am mindful not to ascribe undue influence to Pinkvoss nor to diminish Anzaldúa's genius, recognition of which continues to grow. Simultaneously, acknowledging the history of Borderlands as an influential book with roots in lesbian-feminist publishing and the significant role that Pinkvoss played as an editor is vital. Like many authors, Anzaldúa collaborated closely with her editor and publisher, and Pinkvoss and Aunt Lute influenced how the book was published — and helped to shape its reception in the world. This interracial partnership is an important element of the book's story.

Finally, perhaps most significantly, for the past thirty-five years, Pinkvoss has kept Aunt Lute Books operational — and continued to market and distribute Borderlands. While nearly all other independent lesbian-feminist presses have closed or sold to commercial interests, Aunt Lute remains a beacon of independent lesbian-feminist publishing; Anzaldúa's Borderlands is a beneficiary of the tenacity and grit of Pinkvoss in keeping the press functional and vibrant. Other iconic texts of lesbian-feminism have fallen out of print, some for years, others for decades, but Aunt Lute continues to publish Borderlands, update it regularly, and amplify contemporary voices that engage with the text. The collaborative relationship between Pinkvoss and Anzaldúa demonstrates a partnership between editor and author that embodied feminist visions and helped to solidify a new genre of feminist writing. Today, creative non-fiction, a term which could be used to describe Anzaldúa's bold and innovative writing, flourishes in commercial marketplaces. Anzaldúa's work in Borderlands and her work as a public speaker and thinker helped create these audiences. Borderlands, the book borne of an interracial feminist collaborative, continues to influence the world today.

A concluding story about Borderlands and Anzaldúa: On September 26, 2017, the US daily Google Doodle featured Gloria Anzaldúa, recognizing what would have been her seventy-fifth birthday. Fans of Anzaldúa celebrated this milestone, a form of contemporary digital recognition of the extraordinary thinking and writing that Anzaldúa brought to the world. Although this Google Doodle does not acknowledge explicitly the publishing milieu that brought Anzaldúa to the world, it represents the collective labor of lesbian-feminist editors over the past five decades to build a vibrant literary infrastructure for queer writing. Since the beginning of the Women in Print movement, lesbian-feminists have been publishing with increasing savvy and skill, resulting in greater context for lesbian-feminist authors, broader circulation beyond lesbian readers, a transformation of literary canons to include feminist and queer voices, and a reimagining of genres through innovative and experimental writings. The explanation of the Google Doodle rightly celebrates Anzaldúa but does not mention Aunt Lute.74 Lesbian-feminists through their cultural labors challenged this convention of revering writers in isolation from their embedded social networks. Lesbian-feminist visions for cultural work centered not individual genius (though it recognized and appreciated it), but rather community engagements. Lesbian-feminists valued building powerful infrastructure to support transformative visions including in the literary sphere. This editorial labor aspired to historic interventions — and, as these three stories demonstrate, achieved them.

Lesbian-feminist editorial interventions over two decades continue to influence readers and writers today. Lesbian-feminist imaginaries and the labors of lesbian-feminist publishing movements transformed the US literary landscapes; however, through the forces of commodification, their influence is often erased and forgotten. Recognizing these interventions as editorial as well as activist, a duplexity consonant with the intentions of both editors and writers, invites reconsideration of the influence of lesbian-feminists on contemporary editorial practices and recognition of the significance of these roles to a broad literary infrastructure for lesbian, feminist, and queer writing.

Julie R. Enszer, PhD, is a scholar, editor, and poet. Her scholarly book manuscript, A Fine Bind, is a history of lesbian-feminist presses from 1969 until 2009. Her scholarly work has appeared or is forthcoming in Southern Cultures, Journal of Lesbian Studies, American Periodicals, WSQ, Post45, Frontiers, and other journals. She is an Instructional Assistant Professor at the University of Mississippi.

References

I am grateful to the two guest editors of this issue, Tim Groenland and Evan Brier, for the invitation and for the trenchant editorial feedback throughout the process. Feedback from two anonymous reviewers was invaluable to my revisions of this article as was feedback from Annie McClanahan, Arthur Wang, and Nia Judelson. I appreciate all of the ways that these careful readers and generous interlocutors strengthened this essay. Finally, appreciation to all of the women in the Women in Print Movement for their labor, their words, and their visions.

- Trysh Travis, "The Women in Print Movement: History and Implications," Book History 11 (2008): 276. I postulate that one reason for the lack of attention to editorial work by feminists in the Women in Print movement emanates from one strand of feminist analysis that viewed editorial work as male, or patriarchal, and an intrusion on women's work and vision for their work. During the 1970s, women sought to challenge and overthrow multiple structures including literary structures and systems. The Women's Press Collective, for example, published their first anthology with no authors attached to the work to challenge literary star systems and systems of authorship. At the same time, of course, other feminists sought egalitarian structures to replace patriarchal systems of domination. This article honors multiple analyses of power and engagements with editorial systems by feminists. [⤒]

- Jaime Harker, The Lesbian South (Charlotte: University of North Carolina Press, 2018). Kristen Hogan, The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016). Junko R. Onosaka, Feminist Revolution in Literacy: Women's Bookstores in the United States (New York: Routledge, 2006). [⤒]

- K. Liddle, "Distribution Matters: Feminist Bookstores as Cultural Interaction Spaces," Cultural Sociology, 13, no. 1 (2019): 58. [⤒]

- Cait McKinney, Information Activism: A Queer History of Lesbian Media Technologies, Sign, Storage, Transmission (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 108. [⤒]

- Donna Lloyd Ellis, "The Underground Press in America: 1955-1970," Journal of Popular Culture 5, no. 1 (1971): 102-24; Abe Peck, Uncovering the Sixties: The Life and Times of the Underground Press (New York: Pantheon Books, 1985); John McMillian, Smoking Typewriters: The Sixties Underground Press and the Rise of Alternative Media in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); Peter Richardson, A Bomb in Every Issue: How the Short, Unruly Life of Ramparts Magazine Changed America (New York: The New Press, 2009). [⤒]

- Martin Meeker, Contacts Desired: Gay and Lesbian Communications and Community, 1940s-1970s (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006); Rodger Streitmatter, Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America (Boston: Faber and Faber, 1995); Jafari S. Allen, There's a Disco Ball Between Us: A Theory of Black Gay Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2022); Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, The Poetics of Difference (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2021); Darius Bost, Evidence of Being: The Black Gay Cultural Renaissance and the Politics of Violence (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018). [⤒]

- Benjamin Serby, "'Not to Produce Newspapers, but Committed Radicals': The Underground Press, the New Left, and the Gay Liberation Counterpublic in the United States, 1965-1976." Journal of the History of Sexuality 32, no. 1 (January 2023): 2. [⤒]

- Susan L. Greenberg, A Poetics of Editing (New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2018), ix. [⤒]

- Abram Foley, The Editor Function: Literary Publishing in Postwar America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021), 7-8. [⤒]

- June Arnold, "Feminist Presses & Feminist Politics," Quest 3, no. 1 (Summer 1976): 19. [⤒]

- Arnold, "Feminist Presses & Feminist Politics," 19. [⤒]

- Greenberg, A Poetics of Editing, 117. [⤒]

- Peter Ginna, ed., What Editors Do: The Art, Craft, and Business of Book Editing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 7-11. [⤒]

- Arnold refers to "random houses" in the profile of Diana Press by Lois Gould, "Creating a Women's World," New York Times Magazine, January 2, 1977, 34, 36-38. In the Quest article, she refers to these presses as "finishing presses" because they want to end the feminist movement. "Male-stream" as a portmanteau did not emerge until 1981 in Mary O'Brien's The Politics of Reproduction (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981), but aligns with Arnold's general outlook. [⤒]

- Foley, The Editor Function,5. [⤒]

- Ibid., 95. The third chapter, "Editing and the Ensemble" considers Mackey's work on Hambone in depth. [⤒]

- Joan Larkin, in-person interview, Brooklyn, NY, May 26, 2011. Jan Clausen provided Kathryn McHargue's name in a personal email correspondence, June 30, 2011. [⤒]

- Larkin, interview, 2011. [⤒]

- A complete bibliography of all publications of Out & Out Books is available at the Lesbian Poetry Archive. Out & Out Books also distributed Susan Sherman's Women Poems, Love Poems, though they were not involved in publishing the collection. Sherman, the long-time editor of the feminist journal Ikon, and a transformative figure in poetry and activism, deserves further consideration by literary critics. [⤒]

- Lois Gould, "Creating a Women's World," The New York Times, January 2, 1977, p. 11. [⤒]

- Bibliographies of these presses and others are available at the Lesbian Poetry Archive. I have analyzed some of these presses in two articles: "Lavender Press, Womanpress, and Metis Press: Lesbian-Feminist Writers and Publishers in Chicago during the 1970s," Bibliologia: An International Journal of Bibliography, Library Science, History of Typography and the Book 10 (2015): 71-83 and "Night Heron Press & Lesbian Print Culture in North Carolina, 1976-1983," Southern Cultures 21, no. 2 (Summer 2015): 43-56. [⤒]

- Larkin, interview, 2011. [⤒]

- Martha Shelley, interview with Kelly Anderson, transcript of video recording, October 12, 2003, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection, 50. [⤒]

- Shelley, interview, 51. In her 2009 memoir A Simple Revolution (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2012), Grahn describes this communal household as central to their feminist and publishing work. [⤒]

- Larkin, interview, 2011. [⤒]

- Joan, Polly, and Andrea Chesman, Guide to Women's Publishing (Paradise: Dustbooks, 1978), 158. [⤒]

- Jan Clausen, Apples and Oranges (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), 130. [⤒]

- I explore Foster and Sex-Variant Women in Literature through the lens of authorized and unauthorized lesbian histories in "Lesbian History: Spirals of Imagination, Marginalization, and Creation," The Routledge History of Queer America, ed. Don Romesburg (New York: Routledge, 2018), 237-249. [⤒]

- Larkin, interview, 2011. [⤒]

- In Apples and Oranges, Clausen describes her book as "self-published" Clausen, 141. While I appreciate Clausen's characterization of the book in her retrospective narrative, self-consciousness about "self-publishing" during the 1970s and the first half of the 1980s does not seem predominant in archival sources. [⤒]

- Larkin, interview, 2011. [⤒]

- Larkin, interview, 2011. [⤒]

- Out & Out Books also distributed Susan Sherman's Women Poems, Love Poems in 1977; Sherman had printed the book earlier and it languished without distribution. Distribution of feminist books during the 1970s is a rich and interesting story. Kaja Marczewska's forthcoming chapter " [⤒]

- Adrienne Rich, On Lies Secrets, and Silence (New York: W. W. Norton, 1979), 223. [⤒]

- Rich, On Lies Secrets, and Silence, 1979. [⤒]

- For more information on Conditions, see Julie R. Enszer, "'Fighting to Create and Maintain Our Own Black Women's Culture': Conditions Magazine, 1977-1990," American Periodicals 25, no. 2 (Fall 2015): 160-176. [⤒]

- Ellen Shapiro, telephone interview, July 5, 2011. [⤒]

- Larkin, interview, 2011. [⤒]

- Larkin, interview, 2011. [⤒]

- Larkin, interview, 2011. [⤒]

- Shapiro, interview, 2011. [⤒]

- Shapiro, 2011. [⤒]

- Most recently Klepfisz's newest poetry collection Her Birth and Later Years (Wesleyan University Press, 2022) won the Audre Lorde Prize for Lesbian Poetry from the Publishing Triangle. [⤒]

- W. W. Norton, Rich's publisher, issued the acceptance speech as a press release the next day. The full statement was published in off our backs 4, no. 7 (June 30, 1974), 20. [⤒]

- David Grundy's forthcoming book brilliantly maps lesbian-feminist poetry networks including lesbian-feminist ones in San Francisco and Boston. David Grundy, Never by Itself Alone: Queer Poetry in Boston and the Bay Area, 1944-Present (New York: Oxford University Press, forthcoming). [⤒]

- Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (New York: Routledge, 1979), 95. [⤒]

- A more complete history of Diana Press is in my dissertation, "The Whole Naked Truth of Our Lives: Lesbian Feminist Print Culture from 1969 through 1989," University of Maryland, 2013, and "Feverishly Lesbian-Feminist: Archival Objects and Queer Desires," Out of the Closet, Into the Archives: Researching Sexual Histories, ed. Amy L. Stone and Jaime Cantrell (Albany: SUNY Press, 2015). [⤒]

- Paul Lauter, Canons and Context, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), 169. [⤒]

- Ibid., 23. [⤒]

- History of Diana Press - 1976; undated document, File Drawer #1, Diana Press Papers, June L. Mazer Lesbian Archives,Los Angeles. [⤒]

- Press Release from Diana Press, undated, Mazer Archives, Drawer #1 [⤒]

- A complete bibliography of Diana Press is available at the Lesbian Poetry Archive. [⤒]

- In her memoir Judy Grahn writes, "the team of Laura [Brown], Coletta [Reid], and Casey with their strongly developed working-class consciousness, told me they had become alarmed that our work would disappear into the shadow of the middle-class East Coast poets, Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich" (A Simple Revolution, (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2012), 243.) A 1979 document of the history of Diana Press (Mazer Archives) also discusses Diana Press's concern about the growing interest of New York publishers in feminist and lesbian work. [⤒]

- Grahn, 244. [⤒]

- Grahn's collection The Work of a Common Woman was published by St. Martin's Press, a commercial publishing house, in 1980, and independent, commercial publisher Beacon Press published her award-winning narrative non-fiction book Another Mother Tongue. Grahn did have commercial publishers, but her most consistent publishers have been and continue to be independent feminist presses. Parker's work has always been published exclusively by independent feminist presses. [⤒]

- When Persephone Press entered bankruptcy, Kitchen Table Women of Color Press became the publisher of This Bridge Called My Back releasing their first edition of the book in 1983. [⤒]

- Cherríe Moraga, "Politics of Difference," Xicana Codex of Changing Consciousness, (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 122. [⤒]

- Ibid. In 2002, Anzaldúa and AnaLouise Keating edited This Bridge We Call Home, which more closely hewed to Anzaldúa's vision. [⤒]

- Ricardo F. Vivancos-Pérez, "The Process of Writing Borderlands/La Frontera and Glora E. Anzaldúa's Thought," in Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (The Critical Edition), ed. Ricard F. Vivancos-Pérez and Norma Elia Cantú (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2021); Norma Elia Cantú, "Doing Work that Matters," Borderlands; Joan Pinkvoss, "Editor's Note," Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza (25th Anniversary, fourth edition) (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 2012), 15-16; M. Bałut Fondakowski, "Aunt Lute Books on Controlling the Narrative . . . Or Not," Women's Studies Quarterly 50, no. 3 (2022): 64-75. [⤒]

- Fondakowski, 65. [⤒]

- Vivancos-Perez, 21. [⤒]

- In-person interview with Joan Pinkvoss, June 26 and 27, 2013, San Francisco, CA. [⤒]

- For more information on Aunt Lute see, Julie R. Enszer, "The Business of Feminism Endures: Four Decades of Spinsters Ink and Aunt Lute Books Publishing Lesbian-Feminist Books in the United State," Feminist and Queer Activism in Britain and the United States during the Long 1980s, ed. Charlotte Jeffries and Sarah Crook (Albany: SUNY Press, 2022), 285-305. [⤒]

- Pinkvoss, interview, 2013. [⤒]

- Pinkvoss, interview, 2013. [⤒]

- Pinkvoss, interview, 2013. [⤒]

- Pinkvoss, interview, 2013. [⤒]

- Pinkvoss, interview, 2013. [⤒]

- Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (San Francisco: Aunt Lute / Spinsters, 1987), front matter. [⤒]

- See for example Audre Lorde's Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (Watertown: Persephone Press, 1982), Minnie Bruce Pratt, Rebellion: Essays 1980-1991 (Ithaca: Firebrand Books, 1991), and Mab Segrest, My Mama's Dead Squirrel: Lesbian Essays on Southern Culture (Ithaca: Firebrand Books, 1985). Recent, wonderful scholarship about autotheory, driven by Lauren Fournier's Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2021) demonstrates the continued significance of genre-challenging personal essays. [⤒]

- Janet Bletcher et al., "Best Books of 1987," Library Journal, January 1, 1988, 40. [⤒]

- Pinkvoss, interview, 2013. [⤒]

- Gloria Anzaldúa, editor, Hacienda Caras / Making Face, Making Soul: Creative and Critical Perspectives by Feminists of Color (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1990), front matter. [⤒]

- For more information about the Google Doodle, visit https://www.google.com/doodles/gloria-e-anzalduas-75th-birthday (accessed November 1, 2021). [⤒]