Issue 9: Editing American Literature

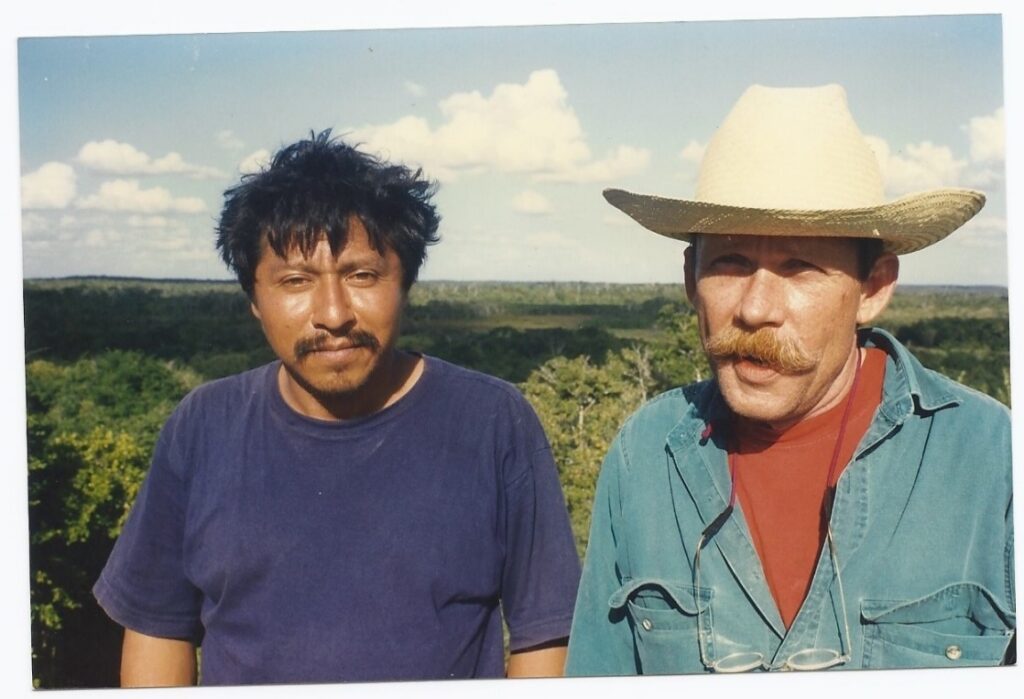

The words in my title — Escríbelo como si me lo estuvieras contando ("write it as if you were telling it to me") — were spoken by Dick Reavis, a white bilingual journalist and former senior editor for Austin's Texas Monthly, to Ramón "Tianguis" Pérez, a Zapotec Mexican and a campesino (farm worker) in his native state of Oaxaca. At age 20, after participating as a guerrillero (guerilla fighter) in a social movement in Oaxaca in 1978-79, he became a mojado, an unauthorized border crosser.1 Together, they wrote about Pérez's crossings of the US-Mexico border. Diary of an Undocumented Immigrant (1991) is Reavis's edited and translated version of Pérez's Diario de un mojado (2003).2

Drawing upon a methodological mixture of archival research, oral history, and close reading, I use this essay as an opportunity to bring into focus the unusual editor-author dynamic by which Reavis and Pérez co-created these unique texts. I recount the unconventional collaborative arrangement of editing and writing between these two men. Their collaboration is important not only for the texts they produced but for the material conditions that led to their production and for how their editor-author relationship developed. I begin with an exposition of Spanish-to-English/English-to-Spanish literary history in the US in order to situate Diary and Diario; I thereby show how they engage with this context of Latinx publication and translation.3I then show how Reavis manages Pérez's physical movements in time and space, how he "directs" and participates in Pérez's transborder crossings in 1978 and 1983, how he urges Pérez to write about his unauthorized crossings to fill what he saw as a market demand for a book that would document an undocumented life in the voice of the undocumented subject, and how he serves as Pérez's agent and translator. I end by explaining how Reavis takes on his role as editor, and manages Pérez as author, to produce the actual texts. Reavis's work far exceeds what we conventionally think of as an editor's role.

Intersecting and overlapping my analysis is the expression "relations of writing."4 I use it to show how the production of Diary/Diario troubles the reductive marketing strategies that publishing companies use to shape an audience's thinking about modern editor-author relationships. I refer to the paradox by which the singular author, the star of the show, is visible in writing and marketing the product, while the editor's labor, indispensable in the process of making that same product, remains invisible. Published texts give the impression of conclusiveness. The final product tends to hide the intricate relations between editor and author. Viewing Reavis's unorthodox behavior and editorial practices through the prism of "relations of writing" exposes how publishing companies misalign the editor's role (editors being at once "everywhere and therefore nowhere" and foregrounds the interdependence of editor and author.5 The concept helps me to open a window into the binational "relations of writing" between editor and author that are required to produce a contemporary cross-border, cross-linguistic narrative.

Diary/Diario emerges from the duration of the men's friendship, mutual support, and trust. The friendship is a complicated one, involving personal commitment to the publishing process, an imbalance in their racial and social status, a movement between languages, and the idiosyncratic realities of the Mexico-US border that they negotiate. The international border, their pivot, becomes a theatrical stage and Pérez a physical actor in a cartographic history of Mexico-US migrations. Reavis convinces him to pose, to act the role of a common mojado who crosses presumably for economic betterment, a posing that produces an ironic doubling of character. Reavis becomes a "stage director," instructing Pérez on what to do, where to cross, and where to reunite. When Pérez agrees to write about his mojado experiences, Reavis functions as his editor (a mediator between author and text), and directs Pérez's writing of Diario. There is transnational movement across a juridically mapped border between two nations when the men engage in an epistolary correspondence — a "scripting" — as they rework drafts on typewriters, which leads to the making of the actual texts. Without Reavis's direction, and without Pérez granting him the opportunity to support, commit, and participate in his development from a quasi-lettered person to a writer, the books never would have existed. Reavis takes on something few modern editors would: he edits someone with slim prospects of becoming an author, someone who never dreamed of becoming one, because becoming one was unthinkable for him.

A published author himself, Reavis functioned as Pérez's book agent by securing publication on the US side of the international border.6 He aimed to get the book out fast, to use the migrant's own words, "a make-do operation, from start to finish," according to Reavis.7 Reavis pitched Pérez's Spanish manuscript to Mexico City publishers and his English translation of Pérez's manuscript to New York publishers (Houghton Mifflin, Penguin USA, to name two) and university presses in the southwest. No single-language publisher in either country offered a contract. Reavis tried his own agent, Esther Newberg, in New York, but she did not see a market for it. Andy Dutter at William Morrow told him the manuscript was quite interesting and "heart-wrenching," but "a commerce-minded little guy with horns and pitchfork kept whispering in [his] ear" that the book would not sell in their market.8 He then reached out to Jorge Castañeda, an academic, writer, presidential adviser, and Mexico's Secretary of Foreign Affairs in the late 1980s.9 This was wise, since "[the] weight of most of the publishing industry in Mexico rests on the shoulders of the State."10 At first, Castañeda held out hope for Mexico's book market, but nothing came of it. Handling a non-author with no platform or previous visibility was a daunting challenge.

Reavis's persistence finally paid off when he met Nicolás Kanellos at the Texas Institute of Letters. Kanellos was Arte Público's founding publisher in 1979; he has operated since as its editor-in-chief. Arte Público is a respected university-affiliated press with longstanding roots in Latinx communities; a successful track record of publishing English, Spanish, and bilingual editions; and significant symbolic capital.11 Through Arte Público, Diary would have through five printings, Diario three. Kanellos, a key connection in the relations of writing that led to Diary/Diario's publication, anticipated that a testimonial book by an undocumented migrant about his experience would capture a Latinx audience's attention.

Literary History

Latinx publishing underwent an unprecedented transformation in the years 1990-2010. Multinational corporate publishers based in New York — the heart of conventional literary publishing — for the first time released a rich array of English-language Latinx narrative fiction in efforts to address the dramatic growth of an educated Latinx readership. They designed a thorough plan to acquire print versions and eBooks of books previously published by independent Latinx presses since the 1970s, as well as new Latinx narratives.12 Prior to this shift, New York houses had only rarely published Latinx literature in English. Subsequently, Simon & Schuster, Random House, and Harper Collins made an even more dramatic editorial decision, also for the first time: they generated the Rayo, Vintage Español, and Atria Books Español imprints to publish translations of Latinx texts from English to Spanish for domestic and transnational Hispanophone markets. I call this pattern of translation "reverse cross-over"since the simple "cross-over" describes movement of visual and literary material from a smaller audience to a larger audience, as would be Spanish to English. The "cross-over in reverse" is movement from English to Spanish, as it is in the case of the mainstream translations. This movement of simple "cross over" and "cross-over in reverse" is true of English and Spanish in both domestic and transnational markets.13 These were unprecedented publishing and translation processes.

Prior to this moment, during the 1970s, four of the five original Spanish editions of Latinx-Chicano/a narratives were published by emerging independent Chicano presses with committed staffs and limited budgets. No Latinx narrative in English was translated to Spanish by independent Latinx presses or by commercial presses in the 1970s, suggesting that "Spanish" had not yet become a national marketing strategy. It was not until 2002 that Bilingual Review Press issued El camino a Tamazunchale, a translation of Ron Arias's The Road to Tamazunchale (1978).14 The Chicano movement classics, José Antonio Villarreal's Pocho Rodolfo, Anaya's Bless Me Última, and Sandra Cisneros' The House on Mango Street were among the bumper crop of translations to Spanish in the two-decade period of the reverse cross-over turn taken by Anglophonic New York presses.15 Up until the 1990s, modern readers of Latinx literature, regardless of language and genre, had relied solely on small independent Chicano presses anchored in local universities whose editorial boards consisted of Chicano/a faculty and students. Quinto Sol Publications, Arte Público Press, Bilingual Review, and other ethnic publishers defined the literary field of Latinx-Chicano creative writing in English, Spanish, and vernacular dialects.16 These presses with relatively small markets filled the void of Latinx books, generating a responsive space in the publishing industry and developing a steady audience for them. Both Diary and Diario appeared at the apogee of a publishing turn taken by New York presses. Reavis commented facetiously to me about Kanellos's decision to publish Diario in 2003: "He saw New York coming."17 Reavis's joke aside, Kanellos made a smart financial move and took advantage of the turn to Spanish publishing which mainstream presses had tapped into since the 1990s. As Bilingual Review had done with Arias's text in 2002, he intervened in the larger Spanish-language marketplace.

The modern literary publication history of Latinx-Chicano narratives thus includes the Spanish editions (Miguel Méndez, Aristeo Brito, and Alejandro Morales,18) and Quinto Sol's two bilingual editions, in addition to Bless Me, Última. A second strand in this history is the publication of Latinx narratives in English and of reverse cross-over translations. The most notorious text in this second strand might be the controversial mega best seller American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins, translated into Spanish by Harper Collins's Vintage Español with the more prudent title, Tierra americana.19 Diary/Diario occupy an interstitial place, simultaneously engaging and disengaging from the two axes: the independent Latinx publishing and the New York Mainstream publishing. Like the many translations done by New York presses (and the few by Chicano presses), they are intranational translations, translated and published within the same country and geared towards a US audience.20 Diary's distinction, however, is that, from the outset, it was a translation of a manuscript written by a Mexican Zapotec in Mexico, yet it functioned like the English originals of both New York and Chicano presses: for twelve years Diary was the only version on the market. If readership rather than publication date is the deciding factor, then the honor of "original text" must go to Diary. Unlike the other translations, Diario went full circuit, from a manuscript in Spanish to a publication in English and then to a publication in Spanish. Like the few translations to Spanish done by Chicano presses, these duo texts were published by Arte Público Press, originating not in New York but in Houston, Texas. Their most important distinction for my purposes is that the Spanish-English-Spanish productions of Diary/Diario explicitly draw attention to the distinctive transnational features of the editor-author relationship between and within two national languages and nation-states.

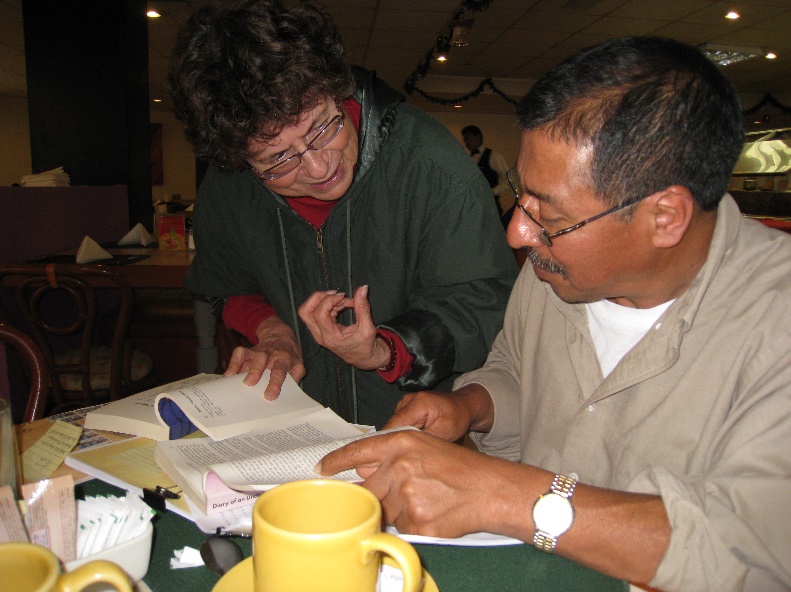

My analysis of this relationship is based on interviews I conducted with Reavis and Pérez over a ten-year period, from 2011 to 2022. It is clear from my interviews and conversations with them that memory of the events that occurred between 1978-1986 is imperfect. It is hard enough to remember events forty years removed from the present but especially hard when forgetting is compounded by the desire to conceal clandestine acts. The passage of time since the 1980s explains why Pérez would sometimes say to me, "estoy escarvando mis recuerdos" or "No me acuerdo," which would segue into a resigned expression: "los años" ("I'm digging into my memory"; "I don't remember"; "the years!,"21 Though I highlight Pérez's two main border crossings, he crossed multiple times. It is difficult for Reavis and Pérez to isolate the events connected to each sojourn on each side of the border. My questions to them were aimed at uncovering events which they for a time wanted and needed to hide. I thank them for their patience and the time they took to answer all my questions to the best of their recollection.

1979: A Guerrillero Becomes a Mojado

Ramón "Tianguis" Pérez is the second-oldest son of six children in a Zapotec peasant family in Macuiltianguis, a remote village in the Sierra Juárez Norte region of Oaxaca, about a three-hour drive from Oaxaca City, the state's capital.22 He is literate, with the equivalent of a high-school degree. In the late 1970s, Austin's Texas Monthly, "the national magazine of Texas," sent Dick Reavis, the only Spanish-speaking contributing writer on its board, to Mexico City to cover a peasant revolt in Oaxaca, one of several indigenous movements in the states of Guerrero, Michoacán, Morelos, Veracruz, and Oaxaca. Guerrillero groups, some armed, had risen against Mexican bosses and corporations who had seized comunero lands, a communitarian management of farms and villages owned in common by Zapotec people in the Sierra Norte of Oaxaca.23 The guerrilleros rebelled against the owners of paper factories (papaleras) who had exploited the land that villagers had owned for years. Pérez was a guerrillero in this uprising in Oaxaca, which Texas Monthly sent Reavis to cover. Reavis wrote about these uprisings in "The Smoldering Fire" for Texas Monthly. He masked Pérez's character: a "rocking guerrilla" disguised as "Trueno" ("thunder"); a "twenty-year old Zapotec from Oaxaca . . . who speaks Spanish without an Indian accent . . . with thick muscular limbs" and "straight, shimmering black hair."24

A young man looking to belong somewhere, Pérez became involved with a group of revolutionaries led by Francisco Medrano-Mederos, whom villagers called Güero, due to his light skin, auburn hair, and blue eyes. Güero shortened Pérez's village name, Macuiltianguis, to "Tianguis," the nickname he uses on his book covers, which means "poor peoples' market."25 He also made Pérez and his compañeros aware of the social-economic injustices in their villages. That Pérez kept this name and used it as part of his identity as a writer suggests that he valued the connection Güero had made to his Zapotec village and his ambitions for its social and economic betterment. Pérez's role was to operate as a liaison between Mexico City and the armed peasants hiding in the jungles and hills. Medrano-Mederos sent Pérez to meet Reavis in Mexico City to guide him through the treacherous mountains of Oaxaca and Veracruz. Pérez and Reavis first meet in Mexico City in 1978. Thinking back to this transformative moment in his life, using an expression more richly evocative than its counterpart in English, Pérez told me: "Conocí la cara de Dick. Siempre hemos estado como amigos" (emphasis mine). ("I met Dick. We have always been friends,"26 The word conocí from conocer, suggests something deeper than simply to meet someone: an affective feeling, for example, a moment of recognition, a bonding, a foreshadowing of the depth of a relationship. When the bosses assassinated Güero in 1979, Pérez and some compañeros were arrested, imprisoned, tortured, and released. 27 Traumatized by his prison experience, unable to return to his family village because his actions had made it vulnerable to government attack, Pérez decided to telephone his friend Reavis, now back in Austin. Reavis put the idea into his head of crossing the border. Pérez decided to cross.

Reavis gave Pérez shelter in his house in Austin: "me dio asilo en su casa."28 Pérez talked to me about the six months he stayed at Reavis's house, a period in which their relations of writing developed around different typewriters, books in Reavis's library, conversations about writing, and experiences of editing. Pérez, for example, was fascinated by the way Reavis sat at a typewriter and wrote, using all ten fingers: "Yo pensaba que era electricidad."29 He thought if he used this motorized machine, he would be able to reproduce letters on the page too. He would practice on it when Reavis was at work. "¡Yo jamás! Con dos dedos."30 He told me, "We finally bought me a typewriter at a bazaar but not an electric one"31 Years later, Pérez continued to use a manual typewriter like the one he had bought in Texas with Reavis to prepare the manuscript he sent across the border. In pre-computer times, Reavis's and Pérez's typewriters created a "mechanical form" of literary production that brought them closer to print publication. The physical production of Pérez's writing depended on (and referred to) his relation with Reavis. The typewriter figures importantly in Pérez's awareness of letters and writing.

In his guerrillero years, Pérez had done some editing and writing for El comunero, Güero's newspaper. He and his compañeros reported on regional problems. There was always someone to check the form and content. Filled with youthful idealism, he wanted to pull every mode of injustice his group stood against into his writing: capitalism, imperialism, oppression. But Güero would squash his excessive fervor and tell him to write about one topic ("un tema"). Pérez's first editor-mentor was Güero— "Fue mi mentor."32

Pérez read books in Spanish in Reavis's library. He needed to read more; his vocabulary needed to grow. At first, writing was hard, he told me, harder than what he had imagined. Reavis gave him the key; he uttered the words (of my title) he needed to hear to feel more confident about his writing: "escríbelo como si me lo estuvieras contando."33 He told him to dictate his writing as though talking to him. Reavis is his support; he became his second mentor. To this day, Pérez refers to him as el maestro. These relations of writing—el Güero, el comunero, the typewriters, the books in Reavis's library, and Reavis's advice to dictate his writing—were important in Pérez's relationship to Reavis.

Pérez returned home, and after a few years, he was able to write something acceptable. On different sides of the border in the early 80s, they established yet another relation of writing. They communicated regularly through mail and occasionally through phone calls, even though Pérez had to commute to Oaxaca City to call him. Pérez mailed paragraphs to him for comments on how to improve what he wrote. "A letter took between 20 to 30 days from Texas to my village," Pérez said in an email to me.34In the letters, Reavis would say, "aquí te falta, aquí te sobra"35 The guerrillero experience was foremost in both their minds. Reavis promised him before he left Texas a dollar for every page he would write on the guerrilla movement because he thought the topic would be important to Mexican and US historians. "About a year later he came back" with the manuscript, and "a month or so later, I started reading [it] and realized that though he couldn't spell, he was a born writer."36 In one of his moves, however, Reavis misplaced the manuscript. Years later, Pérez wrote a second manuscript about his time in the Oaxaca uprising that became Diary of a Guerrilla, edited and translated by Reavis, published by Arte Público in 1999, eight years after Diary and four years before Diario. Diary of a Guerrilla was never published in Spanish.

What's striking are the crucial decisions and the considerable personal investment Reavis made in 1979 — he not only suggested Pérez cross the border but oversaw his migration journey across the frontera in 1979. These acts were transformative events for both men. The border they negotiated in person became the axis on which Pérez's writing and Reavis's translation and editing revolved. Pérez would repeat the act of border crossing in 1984 and convert it into the subject matter and theme of Diary, his most important book. Reavis would play a multifaceted role: mentor, cheerleader, go-between, advocate, editor, translator, agent. The border-crossing is the genesis of Pérez's diaristic account. Now an ex-guerrillero, Pérez then becomes a mojado, and eventually an author.

1984: Staging a Border Crossing: A Mojado Poses as a Mojado

In the early 1980s, forty undocumented migrants were found dead near San Antonio. Like the tragic events we continue to hear about today, they had suffocated in a truck driven by coyotes who abandoned it upon hearing la migra was nearby. At a standstill, the truck had no ventilation; the migrants died in the sweltering tractor-trailer. This incident aroused Texas Monthly's interest in doing a story about coyotes trafficking migrants across la linea. Pérez remembers, "It was the reason [Texas Monthly] became interested in border crossings."37 They wanted Reavis to do the story. Since about 1982, Pérez had returned home (en mi pueblo). Knowing it was unlikely that he could convince the coyotes he was a mexicano, Reavis wrote to Pérez to ask him to accompany him on the trip. This would bestow credibility on the project. The intent — at first — was for Pérez to be his guide on a dangerous journey in the northeastern region (around the twin border cities of Piedras Negras-Eagle Pass and Nuevo Laredo-Laredo). Reavis's scheme, Pérez told me, was to disguise himself in brownface as a stereotypical "mexicano" — sombrero, moustache, serape and all — and to pass himself off as a deaf-mute to hide his gringo accent.38 Pérez would do the talking.

Pérez packed himself off and travelled north to accompany Reavis. Meanwhile, Reavis tried to convince Texas Monthly that Pérez could do the fieldwork and write the story. Pérez told me Reavis had translated one paragraph he sent him and showed it to his editors at Texas Monthly to assure them that he could write.39 Convinced he could tackle the job on his own, Texas Monthly agreed to hire Pérez, expenses paid. Pérez agreed to pose as a mojado, freelance, and become the sole lead reporter. The stage was set. In a plan bordering on editorial espionage, Reavis directed Pérez's physical travels and "acting" in a migrant camp. Pérez contributed authorial authenticity to his assumed mojado pose. He went "undercover" and acted the part of a mojado in the flesh — the perfect hoax, indistinguishable from the real thing in every aspect. Years later, Reavis would edit Pérez's writerly movement on the page.

Reavis encouraged Pérez to practice "hang-out" journalism: to live with and like the subjects he covered. He juggled two images of himself. He perceived himself distant from the real mojados because he was performing a job ("I had been contracted to do the job"/ "Iba yo contratado")40 and knew that his migrant-compañeros (and the coyote) perceived him to be a mojado like themselves. He performed, was paid to act like a migrant seeking to cross. As a rule, mojados/as aim to deceive US authorities, but given this peculiar situation, he must also have to deceive his paisanos and coyotes. Pérez convincingly played an "authentic" fraud. Pérez, an undocumented migrant, acted like an undocumented migrant to document the border-crossing experiences of undocumented migrants.

To Pérez, a real mojado is a needy person.41 The difference between a needy mojado crossing to work and a mojado freelancing for a magazine to write about an unauthorized border crossing was significant to him because he feels payment for work legitimizes him. Pérez did not know that his crossing north was the gateway to intellectual work — writing magazine articles will lead to a book.

This was a good gig for Pérez. He knew the role, the terrain, the migrant slang, and the crossing-points; he had no need for a physical disguise, and he was paid well. Pérez told me that once he crossed, he was to meet Reavis in Piedras Negras, a border town in the state of Coahuila in northeastern Mexico, to collect traveling expenses and money to pay the coyote.42 Then, he was to go to Nuevo Laredo, about 127 miles southeast of Piedras Negras and locate a coyote trafficking at least, so Texas Monthly hoped, ten migrants. A windfall came his way when he found a "runner" (a migrant chaser) who connected him with a coyote trafficking seventy migrants. He embedded himself in the migrant camp of mostly Mexican men (three are women from San Salvador, the youngest of whom a coyote raped when entering Mexico) for about two weeks until the coyote gave the signal to attempt the crossing.43 He carried $650.00 on him, with $550.00 hidden in his jacket lining. One night while asleep, he was robbed of his jacket. With only $100 left, he managed to convince the coyote that a friend (he did not identify Reavis) awaited him on the other side and would pay the cost ($600) of his transport. On the first attempt at crossing, la migra stopped the station wagons on the Rio Grande's north shore and discovered three migrants, one of which was Pérez, squeezed into one of the trunks, and turned them back to Nuevo Laredo. Though Pérez saw himself as different from the other mojados, the façade melted in this instance. The migra, the State apparatus, the eye of power, perceived him as a mojado like the others. At this juncture, Pérez faced a difficult decision. What to do? Attempt to cross again or forget the job and make his way back to his pueblo? With no other real alternative in view, desperate, fearing he had ruined the "performance," he called Reavis, who advised him to return to Piedras Negras where he would meet him. Reavis crossed to the Mexican side, hired a patero ("duck man") to ferry Pérez across the river and returned to a US hotel known to both to await Pérez. Pérez arrived and Reavis drove him to his house in Granger.

Reavis persuaded Pérez to do a couple stories for Texas Monthly. "Take me Across the River" relates details of his border crossing, the robbery, and ends with his capture by the border patrol and deportation to Nuevo Laredo.44 "Give me a Job" talks about a Spanish radio station program in Houston called "Yo necesito trabajo" ("I need work") that provides leads about jobs to mojados, as well as Pérez's own fruitless search for work in Houston.45 Reavis edited and translated the stories. The events recounted in these Texas Monthly stories constitute the heart of the first half of Diary and Diario.

The Production of Diario and Diary

This collaborative production originated with Reavis's visit to Pérez in 1988, two years after the latter's final return to Mexico. Married and living at home in Xalapa with his wife and family, Pérez was earning a living roving the streets as a photographer of tourists and local weddings. Earlier, Reavis had suggested that he take the events of the Texas Monthly articles and thread them into a larger narrative. Pérez always humored him in the moment but never followed through: "Dick always told me: you have to write down your experiences as a mojado. I always said I would, but I didn't do it") — until this visit.46 Convinced there was the potential for a book, Reavis nudged and pressed harder. "Tianguis could write the book," Reavis said. "I asked him how much he would need to do it. He went home and — (if you can believe this!) — calculated what it would cost him for paper and typewriter ribbons. I got an advance from Texas Monthly Press for him."47 Reavis had imagined a book and Pérez was now ready and willing to write it.

Pérez wrote and Reavis edited, each one living on opposite sides of the border they crossed that proved so consequential to their lives and formative to their relationship. Reavis once directed the material events of Pérez's migrant life and now edited Pérez as he wrote about those events. He guided, selected, shaped, and linked the episodes into one book. "We were writing to each other and when he was doing the translation, he returned some pages for me to correct or he'd say that dates were missing or that I should rewrite such and such a page to clarify."48

Reavis said that when they exchanged the typed manuscript in the correspondence, Pérez "had made changes in handwriting and in magic marker. I apparently copied that mss. (sic.) and added notations of my own as I translated. In the original, it seems that [Pérez] made his changes in black. In the translation copy, I apparently circled in orange words that I didn't understand and also made notations in pen."49 Pérez also had some thoughts on the process: "I've noticed that some pages are double-spaced and others are triple-spaced, but if you note closely there is also a difference in font. My explanation is that I didn't always use a single typewriter. Another reason — I'm digging into my memory — is that Dick told me to make a clean copy of the entire manuscript. I did it, but also with different typewriters. The pages I thought all right, I did not rewrite. I simply inserted them into the manuscript."50 The mechanical vestiges of writing production in a pre-computer age are in full display—the font of the typed words, the notations in pen, in black and color, the double and triple-spaced lines, and the different typewriters. These vestiges, the duration of time and labor it took to send the manuscript back and forth across the border accentuate Reavis's and Pérez's commitment to the writing process.

Since Reavis was translating the memoir, he did not have to edit Pérez's spelling and grammar in Spanish. In fact, he told me he had nothing to do with the Spanish text. Arte Público would make some micro-edits to the Spanish text when it decides to publish Diario.51 In translating, Reavis followed the draft pages closely but did not preserve every sentence.52 He did press Pérez for clarity and precision on his locations, characters, and events in order to make his English text clear and precise. Pérez told me Reavis would ask him for the meaning of the mexicanismos unfamiliar to him. One example is palahierro, which Reavis renders as "shovel."

Instead, Reavis had developmental concerns. He wanted to string together several stories, assembling them in a chronological sequence with narratological coherence. Pérez and Reavis decided to recreate Pérez's journey and frame the narrative with a single entry and exit (una entrada y una salida) to provide a smoother experience for readers, rather than to burden them with the several crossings that actually took place. They collapsed Pérez's 1979 and 1984 entries into one, without identifying the year: if 1979, the entry is chronologically contiguous with the events of Guerilla, when he does not return to his village after prison; if 1984, the entry corresponds to the time he left his village to accompany Reavis on the Texas Monthly job. Political reasons motivated his flight in 1979; a desire to help his friend pushed him to it in 1984.

It's possible to set the story in either year because editor and author erased the journalistic quest of the 1984 Texas Monthly job, probably to establish a less complicated story for a general US audience. In the book, Pérez did not cross to accompany his friend or to pose as someone he is not. Pérez and Reavis presented him as the common mojado who crosses to improve his economic situation. They created a mojado narrative that fits the familiar trajectory of the undocumented migrants of their day, when men, mainly Mexican, travelling alone, were still the archetype of immigration.53Pérez departs from his village for Piedras Negras — twenty-two hours by bus and over 1,000 miles — as though leaving for the first time (really it is his third, at least) for the usual reasons that drive most Mexican migrants to abandon their homes.54 He writes as an ordinary mojado (un mojado común) — not one financed by a magazine.

Arriving, he starts off in Houston. He wanders from town to town, looking for work. He gives us the familiar trope of men standing at a corner, waiting to be picked for jobs. Discouraged at finding no work, he leaves Houston "una ciudad sin esperanza" ("hopeless city") to try his luck in San Antonio. He finds work at a printing plant for one year, tries to learn English, works at a carpentry shop hoping to learn skills he can take back home.55 After witnessing a worker lose a finger, he quits and visits relatives in Los Angeles. He works at a car wash, amused by the novelty of the machines. Then he moves on to agricultural work (vineyards and tomato fields in Ripon, CA, for $3.35 an hour; cherry harvesting in Oregon for $2 an hour). On the drive to Ripon in the San Joaquin Valley, his thoughts turn to his father, a repeated motif, who worked years earlier as a farm worker ("bending his back" Diary 180 / "doblando el lomo."56 In Ripon, he connects with a mojado community from Macuiltianguis that has set up a hometown association to send money and aid back home. His last job is a waiter in a Chinese restaurant in Los Angeles for $600 a month, plus tips, until he is demoted to dishwasher (el lavaplatos), the lowest position on the restaurant totem pole.57 He decides to return home for good.

Reavis and Pérez conclude the narrative in 1986. Their story occurs at the juncture between the passage of the 1965 Comprehensive Immigrant Reform Law and the most recent and last — to date — Immigration Reform and Control Law (IRCA), signed by Ronald Reagan in 1986, by which 2.8 million received legal residency.58 Even though Pérez has not read the congressional document, Reavis knows what is in it and what it means for Pérez. Perhaps it is a pure coincidence that the law was enacted at just this juncture in Pérez's life. Though he now would qualify for legal residency, Pérez has already decided to forgo a legal existence in the US. He engages in a relation of writing by using the law to contextualize his decision against the possibility of legally immigrating. This is where his story departs from the typical migrant's story. He states his reasons for rejecting the opportunity to live permanently in the US: he had achieved his objective of saving money to improve the life of his family; he did not believe that IRCA would make a substantial difference in his ability to qualify for more than a minimum-wage job; and life in the US was too routinized and alienating for him. Perhaps contrary to popular notions, his rejection suggests that the life this migrant wants — and others who stay out of obligation more than choice — is not consonant with life in the US.

Editing as Selection: "Eso se escribe"

In Diario, Pérez brings conscientiousness to the moment of leaving his village. No longer the migrating pilgrim, he is instead a reflective poet. He draws on his cognitive and emotional memory to think back upon this moment. His feelings are marked by love and nostalgia for his village. "Me invadía cierta nostalgia al alejarme de mi pueblo . . . A mí me gustaba mi pueblo."59 The translation is direct and colloquial, hardly doing justice to the sentiment: "Sure, I know everybody loves his hometown."60 He surveys his village, gives a brief history, explains its ecology and temperate climate, recalls the construction of the federal highway, and ponders how long he will be gone. He drops us into a leave-taking scene: of his mother, a housewife; of his father, a campesino. He is self-reflective about following the same route, physically and figuratively, as his paisano ancestors. His decision to come North, he thinks, is not as painful to him as the disappointment he feels about continuing a pattern that has gone on for decades in his village.61He is aware of his village's four-decade intergenerational migration.

Reavis changes the location of this passage; he puts it about ten pages earlier than where Perez has it in his manuscript. In Diary, it occurs when Pérez leaves his village, and it serves to heighten the distress he feels. "My townsmen have been crossing the border since the forties, when the rumor of the bracero program reached our village."62 Pérez's manuscript has no readerly devices — no chapter or section headings. It is one continuous uninterrupted narrative. This sentence on intergenerational migration appears in a later moment, among events oriented toward action, namely the coyotes (migrant traffikers) driving Pérez to the migrant camp. Reavis's placement of Pérez's reflective comments about his village's migration North better suits the meditative and contemplative mood of Chapter 2, "Headed North."

Reavis offered suggestions paso a paso (step by step) about what to include. Pérez reflects, "As I told him about my experiences, he would say, 'Eso se escribe, Eso se escribe,' y así hasta terminar mi relato."63 Reavis repeated this phrase so often that it became a refrain in their communication. Reavis also told him what to exclude, namely two stories from the draft: a sex scene he thought in bad taste and a crime Pérez witnessed in Mexico City during his guerrillero days. Reavis determined that including the crime story would only jeopardize his standing with Mexican authorities. When Pérez recounted to him a story told to him by Xochimilco, a colorful character he met at the bus station in Nuevo Laredo before going to the migrant camp, Reavis uttered his directorial refrain, "Eso se escribe." Pérez attributed to Reavis a sense for story: "Dick sabía lo que hay que contar" ("Dick knew what I should tell.")64

The character Xochimilco gets his name from his days as "a taco vendor in the Xochimilco district of Mexico City."65 "Soy un corredor" ("I am a runner"), he says, "They call us that because we're always running behind guys that we suspect are headed to the United States."66 He boasts that he works "for the best and the heaviest coyote in Nuevo Laredo. . . . The heaviest."67 His story about crime, deceit, and robbery (even patricide) goes like this. Escaping from Mexican authorities, he wants to cross North, but he is wily enough to know that becoming a "runner" and luring innocent border-crossers — chivos (kids, as in billy goats) or pollitos (chicklings)— to cunning smugglers is profitable.68 A gang member he meets loans him money and offers to forgive the loan if Xochimilco helps him execute a job. The job involves assisting a son to rob his rich father. He reluctantly accepts the job and the gun the gang member gives him. The father gets wind of the hold-up and tries to pull a gun on the thieves. Four men — the briber, Xochimilco, the son, and a friend — kill the father. Reavis might have thought it wise to include Xochimilco's story because it spices up the narrative and matches the images of violence, crime, and danger that a book-buying majority has of the border. His choice may be taken as a forerunner in miniature of the mechanisms that media, misinformed authors, publishers, and editors use to commodify and tokenize migrants and the border in today's conglomerate era.69

Editing as Intervention

I conclude with two more examples of editorial intervention. The first concerns Reavis helping Pérez to write himself out of a difficult moment in the narrative. Pérez recounts an incident that happened in Houston. He is trying to obtain a fake social security card to work. Knowing that he needs an authentic-looking card, he approaches a man he is told makes valid-looking imitations. The place Pérez meets him, oddly, is a used-car lot. As soon as the "guy in greasy overalls working on a motor" learns why Pérez has come, he asks him for a social security number. A circumspect Pérez tells him he does not have it on him. "Ah' ... you want me to invent it for you, isn't that it" the man says.70 The man takes a card from a box and inserts it into a typewriter and writes Pérez's name. Pretending to think of a number, the man "hurriedly types nine numbers on the card." Satisfied, Pérez pays the man five dollars and leaves.

In the real-life episode, not understanding what the words say, Pérez showed the card to Reavis. Reavis explained to him that the imitation was a deceitful invention: the man had staged "a fake of a fake." More than just a fake, the card explicitly announced its deception, warning that it should not be taken for the "real thing."

Not issued by the United States Government

No intent exists to harm or defraud any city, company, or person 71

Pérez expected a copy, yes, but a copy that could pass for the "real thing," as "real" as he was when on assignment for Texas Monthly. He expected the card to be credible enough to use to find a job. Instead, he received a card that conveys its own duplicity. This card intentionally lays itself bare, disavows and flaunts its deceit. Paradoxically, it is not even an authentic fraud.

How does Pérez convey his realization that the card is fake without revealing in the narrative that he showed it to Reavis? Pérez explained to me how Reavis cleared up his confusion.72 I paraphrase his words: "You could say you bought a dictionary and used it to decipher the words." Pérez represents himself in the guise of someone suspicious about the card but also a self-reliant man: he takes Reavis's off-stage advice and writes himself buying an English-Spanish dictionary and translating the words on the card: "Later I spend more than an hour at a table in a hamburger joint, looking up the meanings, word by word. When I've deciphered them, I'm not as proud as I was at first."73 Pérez's explanation of reading a bilingual dictionary —a book that uses words to define words--is awkward, and a stretch to believe. Even if he searched the dictionary "word by word," the duplicitous meaning would be challenging for a non-English speaker to understand, especially for a recent arrival unfamiliar with English words and syntax, and the cultural and linguistic codes he needs to decipher the hoax. The important point about Reavis's off-stage intervention is that it enables Pérez to explain himself out of a difficult spot in the writing without exposing his vulnerability — and Reavis's influence — to his audience. The typewriter that reproduced the fake social security card was able to hide the card's inauthenticity because of its mechanical production script which resembles that of official cards. The dictionary and its production allows Pérez to save face. He presents himself as self-sufficient rather than invoking the help of the anonymous "amigo" he does in other instances.

Pérez follows the codes migrants know to survive and obtain employment. But he is deceived because he believes in the unwritten pact between migrants and those who intentionally overlook their unauthorized status. The man in the parking lot, while known in the community as someone who creates legitimate-looking cards, manufactures a document which explicitly says, "Not issued by the United States Government." He thus produces a card of no use to Pérez — a fraudulent fraud. Though his gesture goes beyond the usual levels of artificiality, it recalls the constructed and artificial reality of national borders, especially in the context of Pérez's story about crossing the Mexico-U.S. border that resulted in a war (1846-48) started over fraudulent claims about border skirmishes. We can also extrapolate the construction of the fraudulent social security card, without the extra level of the card's fakeness, to the Diary itself, which is an authentic fraud because, like all narratives, it offers a constructed reality; it is not reality per se. It is a documented text published by a respectable press in the US by and about an unauthorized migrant.

My final example of editorial intervention occurs in what I elsewhere call the primal scene of the book.74 In this scene, Reavis performs a "cameo" in Diary, a noticeable insertion of himself that interrupts the narrative's flow without revealing his identity as editor. The "cameo" is not in Diario. Instead of analyzing it through the lens of translation, as I did in my book, I see it now from the perspective of an implicit editorial intervention. Reavis's unexpected insertion ruptures the fluency and authority of the author. Its absence from the original Spanish makes the appearance of an editorial presence all the more apparent to a careful reader because it brings the editor explicitly into focus. The scene occurs in the chapter titled "Mojados." Unable to find work, Pérez is told to go to a nearby church. He speaks to a man outside: "'Is it true that here they help wetbacks?' I ask him. I use the usual word in Spanish for wetbacks, mojados."75 No counterpart to this sentence appears in Diario. The phrase "in Spanish" is understandable since Reavis might have wanted to create a sense of linguistic realism. But the rest of this sentence is unnecessary since Reavis elsewhere uses "wetbacks." Inside the church, Pérez meets a woman who seems to be in charge: "'Pardon,' I say in Spanish, 'is this the place where you help wetbacks?'"76

Again, in an immediate aside, Reavis inserts gratuitously, "As always, I use the word mojados," which, of course, he does not, since he almost always uses "wetback."77 The important point is that Reavis unveils the invisible boundary between himself as editor and Pérez as author by inserting an additional sentence. This is more editing than translation since Pérez never wrote this sentence. Reavis thus leaves a vestige of himself as editor.

Conclusion

Reavis thought that Pérez's Diario was an important book to get into print, especially into an English-language market, because it was an account by the migrant himself. He thought there was none from "the horse's mouth."78 Perhaps, Reavis's judgment about Diario's uniqueness in the long literary history of Latinx literature was slightly hyperbolic. He did not know that the contemporary Latinx narratives I've recorded in my opening section are part of the context for Diary/Diario, much less about earlier twentieth-century literary sources that prepared the way.79 This long literary history does not diminish Diary's/Diario's unique contribution. It remains one of the few representations of a border crossing experience by the border-crosser himself. The stars aligned in specific and unique ways for Reavis to push this important text into existence: the dramatic increases of the Latinx population since the 1980s with whom Spanish is associated, the growth and interest in creating a national publishing infrastructure for Latinx literature, the spread and growth of the Spanish language, and the global development and rise of a general-interest and literary Spanish-language industry.

Producing this narrative required a remarkable level of editorial advocacy and support. Reavis may not have known literary history, but he was a feisty journalist-editor-entrepreneur, and with an unusual risk-taking attitude, he was the key link in a chain of events that made these books a reality. He was exposed to the journalism profession early on (his father managed newspapers). As a youth he worked around newspapers and preferred "the company of the printers to that of the reporters. From age thirteen until he left for college he worked part-time in the 'back shops,' learning a variety of printing skills." 80 His experience with printing made him especially attuned to the process of preparing texts for publication. Reavis made crucial decisions that reflect his commitment to Pérez's situation. It is unusual for an editor to take it upon himself to move someone, especially an undocumented person and someone he does not know will become a future author, and oversee his migration across a national border, across languages, and across a process of writing. He promoted Pérez, translated him, and represented him to Texas Monthly, from whose editors he acquired financial backing. At the market level, Reavis was an aggressive salesperson. When the Texas Monthly contract fell apart, Reavis persisted and found Kanellos at Arte Público.81 He had the necessary connections to push Diary through a publishing network.

Pérez too made choices, and his choices were acts of self-definition. He chose to cross and to engage in a writing experiment against significant odds: no platform, no visibility, no publishing history. Though he had writing and reading skills in Spanish and a keen interest in writing, atypical for a mojado, Pérez probably would not have undertaken the composition of a book had Reavis not been in the picture. Nor could Reavis have done it without Pérez — editors cannot edit if there is no writing.

The asymmetries between the two men — in formal education, writing experience, ethnic background, and power — were attenuated by an easy-going collaborative dynamic, equitable in practice. The writing was never about achieving a perfect draft or le mot juste. It was about seeing the book in print and speedily making it available to a US audience.

That Reavis was not a controlling editor and Pérez not a combative author helped the project along. Pérez was always deferent to maestro Reavis. They did not aim to shape a high literary work. Their initial meeting was not one of editor and author. At the time of the Texas Monthly assignment, they had no future publication in mind. They never imagined translating the experience into book form. Neither did they expect their writing and editing to create books with staying power — especially Diary — that sold much better than expected. It is true that their books, like many others, follow the single author format, but from the beginning, Reavis and Pérez's alliance went against standard literary conventions of writing and publication. Many of the elements in their story may be implicit in other author-editor relations — textual staging, translating, framing, and transmission — but their situation made such elements explicit.

The site of Pérez's entry into the US, the genuinely liminal space to which everything in this story connects, is the Mexico-US border, this historic site of authorized and unauthorized crossings. Their experience would be irreplicable today due to greater border enforcement, policing, and vigilance. The conditions they encountered working in the shadows of immigration law in the 1980s are even more dire and dangerous today. Lastly, the relations of writing in this context complicate national and linguistic assumptions because they go beyond the single nation-state framework. Their editorial and writerly labor reflects a consciousness of a greater transborder social unit.

Daughter of Mexican immigrants and raised in East Los Angeles, Marta E. Sánchez is a Professor Emerita of Arizona State University (2004-2014) and the University of California-San Diego (1977-2004). She taught Chicano, Latin American, and U.S. Ethnic Literatures in Spanish and English at both institutions. Sánchez received her doctorate from the University of California, San Diego in Comparative Literature. She is the author of A Translational Turn: Latinx Literature into the Mainstream(University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019); "Shakin' Up" Race and Gender: Intercultural Connections in Puerto Rican, African American and Chicano Narratives and Culture, 1965-1995 (University of Texas Press, 2005); and Contemporary Chicana Poetry: A Critical Approach to an Emerging Literature (University of California Press, 1985). Her articles have appeared in PMLA, Diacritics, MELUS, SigloXX/20th Century, American Literary History, American Literature, Genders, Translation Studies, and Oxford Bibliographies Online.

Banner image by Paul Espinosa.

References

- The term literally means "wetback." [⤒]

- Dick Reavis, trans. Diary of an Undocumented Immigrant (Houston: Arte Público Press, 1991); Ramón "Tianguis" Pérez. Diario de un mojado (Houston: Arte Público Press, 2003). Henceforth Diary and Diario. Reavis titled his original manuscript "Diary of a Wetback." Arte Público changed it to "Diary of an Undocumented Immigrant" because "wetback" is race inflected. Ngai sees it as the most offensive among the liminal status categories in US English for Mexicans who are "outside the normative teleology of immigration" (Ngai 13). I agree. The term is offensive to the people most affected by it. Mae M. Ngai Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004). [⤒]

- "Latinx" is a non-binary gender designation which includes several branches of US Spanish-language origin groups: Chicano/a or Mexican American, mainland Puerto Rican, Dominican, Cuban, and Central American. I mainly lean on Chicano because my central two texts fit this branch most closely. The term "Latinx" is the newest addition to a plethora of options for naming Spanish-language origin groups in the US, but according to polls, it is not widely used or accepted. See Pew Research Center or Gallup[⤒]

- Armando Petrucci (1932-2018) coined this expression. For a more extended understanding of the concept "relation of writing" or "rapporto de scrittura" in the context of the discipline of paleography/history of writing, see Petrucci, "La scrittura del testo" in Letteratura Italiana. Ed. Alberto Asor Rose, vol. 4, L'interpretazione. Turin: Einaudi, 1985, pp.285-3081. I thank Stephanie Jed for drawing my attention to this concept that can be so generative for understanding the production of Diary/Diario. [⤒]

- Susan Greenberg. A Poetics of Editing.(Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018), 5. [⤒]

- Among them, Without Documents (New York: Condor, 1978), Conversations with Moctezuma: Ancient Shadows Over Modern Life in Mexico. (New York: William Morrow, 1990), The Ashes of Waco: An Investigation (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), and If White Kids Die (Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press, 2001.) [⤒]

- Reavis's email to Marta E. Sánchez July 2011. [⤒]

- Reavis shared some rejections letters with me. [⤒]

- Castañeda reviewed Reavis's Conversations with Moctezuma for the NYTimes Book Review. [⤒]

- Cristóbal Pera, "The Promise of Spanish Publishing in Mexico and the United States." Publishing Research Quarterly 31, no. 1 (2015), 73-79. [⤒]

- Kanellos highlights important markers in the evolution of Arte Público Press. One year before the demise of Quinto Sol (see note 16), he had started Revista Chicano-Riqueña in the Midwest in 1973; he moved it to the University of Houston where he founded Arte Público Press in 1979, "convirtiéndose en la editorial hispana más importante del país" (xxix), "The oldest and largest publisher of US Hispanic literature," according to their catalogue. Nicolás Kanellos, ed. En otra voz. Antología de la literatura hispana de los Estados Unidos. (Houston: Arte Público Press, 1988).[⤒]

- Previously published texts include Rodolfo Anaya's Bless Me, Última (1972), Sandra Cisneros's House on Mango Street (1983), and Reyna Grande's Across a 100 Mountains, New York, Atria Books, (2006). The foundational epic poem "I Am Joaquín," by Rodolfo "Corky" González, recited at a Denver conference in 1966, mimeographed, photocopied, and distributed widely in ensuing years, was published in bilingual format by Bantam Pathfinder Editions in 1972. The Spanish translation is anonymous. [⤒]

- For an extended analysis and interpretation of this turning point in the US publishing industry, see Marta E. Sánchez, A Transnational Turn: Latinx Literature into the Mainstream (1990-2010). (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019), especially Chapter 2. [⤒]

- Tempe: Bilingual Review P, 1978/1987. El camino a Tamazunchale. Trans. Beth Pollack and Ricardo Aguilar Melantzón. Tempe: Bilingual Review P, 2002. [⤒]

- Pocho (New York, Anchor Books 1959) appeared as Pocho En Español Trans. Roberto Cantú, New York, Anchor Books (1994); Bless Me Última, published by Berkeley's Quinto Sol in 1972, became Bendíceme, Última (no trans. cited) Grand Central Pub. Hachette Book Group (1992); and Mango Street (1983) appeared with the bilingual title La Casa en Mango Street Trans. Elena Poniatowska, New York, Random House, Vintage Español (1991). To these we can add Denise Chávez's (The Last of the Menu Girls [1986]), La Última de las Muchachas del Menú (2005); Richard Vasquez's (Chicano [1970]), Chicano (2005); and Victor Villaseñor's Macho! (1973) (¡Macho! [2007]). [⤒]

- These dialects include caló (Chicano slang) and pochismos (single English Words adopted to Spanish morphology and phonology). [⤒]

- Phone interview by Marta Sánchez, July 2011. [⤒]

- Peregrinos de Aztlán, Tempe Bilingual Press 1991; El diablo en Texas, Tucson, Ariz: Editorial Peregrinos, 1976, and Caras viejas, vino blanco. Mexico: Editorial Joaquín Mortiz, 1975. These single-language narratives were translated to English in the 1990s (Pilgrims in Aztlán 1991, The Devil in Texas 1990, and Barrio on the Edge 1998 by Bilingual Review. [⤒]

- See Ignacio Sánchez-Prado, "Commodifying Mexico: On American Dirt and the Cultural Politics of a Manufactured Bestseller." American Literary History 33, no. 2 (2021), 371-393. Sánchez-Prado contextualized the English text; Esther Allen provides critical commentary on the Spanish translation, issued simultaneously. "Pies on the Windowsills of 'El Norte,'" Los Angeles Review of Books, Feb 5, 2020. Sánchez-Prado argues that the media apparatus that supported this auto-fictional book misappropriated, serious concerns about contemporary migration and migrants from Mexico and Central America. He says, "a fictional work like American Dirt appropriates these stories [about migrants] and commodifies their mechanisms of empathy through distinct literary devices geared at replacing the voice of authors of memoirs and other migrants themselves"(379); and "many of the most recognized books on undocumented migrant crossings are non-fictional" (379), without directing us to examples. I propose we consider the textual pair, Diary/Diario, non-fictional books on undocumented migrant crossings by a migrant, as one antidote to the unseemly masquerade Sánchez-Prado argues, correctly I think, that Flatiron Books, the publisher, and the Oprah Winfrey Book Club manufactured to insert this book into the topical issue of Mexican migration to the US. [⤒]

- I suggest the term "intranational translations" to differentiate these texts from "international translations" or books authors write in their national language and country and then are translated in the foreign country of the target language. Sánchez Prado offers examples of this separate two-country translational marketing (390). [⤒]

- Pérez

,August 2011, email. All translations of Pérez's statements are mine. [⤒] - Macuiltianguis means "five plazas" in Nahuatl: "macuil" (five) and "tianguis" (mercado or market); the latter is commonly used for "market" in the United States. [⤒]

- The P.P.U.A. (Partido Proletario Unido de América) was the umbrella grouping of guerrilleros in Mexico at this time. [⤒]

- "The Smoldering Fire," Texas Monthly 1978, 80-85, 143-150. [⤒]

- For Pérez's guerrillero activities, see Reavis's translation, Diary of a Guerrilla, by Ramón "Tianguis" Pérez. Houston TX, Arte Público Press, 1999, 65. Reavis's name as translator appears on all front covers of Pérez's books. [⤒]

- Ramón "Tianguis" Pérez, interview by Marta Sánchez, Video Xalapa, 2011. [⤒]

- Pérez talks about this experience in Diary of a Guerilla. (Houston: Arte Público Press, 1999)

,137-144. [⤒] - "He welcomed me into his home." Pérez, August 2011 email. [⤒]

- "I thought it was electricity." Pérez, Video Xalapa, 2011. [⤒]

- "Me never. I typed with two fingers. Pérez, Video Xalapa, 2011. [⤒]

- "en un basar me conseguimos una para mi, pero no eléctrica." Pérez, January 2021 email. [⤒]

- "He was my mentor." Pérez, Video Xalapa, 2011. [⤒]

- Pérez January 2021 email.[⤒]

- Pérez, January 2021 email. [⤒]

- "Here you need more. Here you have too much." Pérez, 2011 Video Xalapa. [⤒]

- Reavis, July 2011 email. [⤒]

- "Fue el motivo para que la revista se interesa por e[l] asunto de la migración." Pérez, 2011 Video Xalapa. [⤒]

- Reavis has no memory of this. Piedras Negras became their customary site of crossing because he and Reavis judged it the safest. [⤒]

- Pérez, January 2021 email. [⤒]

- Pérez, Video Xalapa, 2011. [⤒]

- ("una persona necesitada"); Pérez, Video Xalapa 2011. [⤒]

- Pérez, Video Xalapa 2011. [⤒]

- Diary, 41; Diario, 45. [⤒]

- Ramón "Tianguis Pérez, "Take Me Across the River," Texas Monthly (May 1984), 158-165; 220-29.[⤒]

- Ramón "Tianguis Pérez, "Give Me a Job." Texas Monthly (1984), 144-48; 198-202. [⤒]

- "Dick, siempre estuvo diciéndome: hay que escribir tus experiencias como mojado. Yo siempre dije que sí, pero no lo hacía." Pérez, August 2021 email. [⤒]

- , Reavis, July 2011 email. [⤒]

- "Estabamos en contacto por correspondencia y durante su trabajo de traducción, me regresaba algunas páginas que yo debía corregir o bien que faltaban datos o él me decía que había que reescribir de tal a tal página por falta de claridad." Pérez, Phone interview, January 2011. [⤒]

- Reavis July 2011 email. [⤒]

- "Ya me he fijado que algunas páginas están al parecer en doble espacio y otras en tres, pero si se fija si hay diferencia en los espacios, las hay tambien en los tipos de letra. Mi explicación es que no siempre usé una sola máquina de escribir. Otra causa, - estoy escarbando mis recuerdos-es que Dick me dijo que pasara a limpio todo el manuscrito. Lo hice, pero - tambien con diferente máquina- las páginas que yo consideré que estaban bien, no las reescribí, simplemente las fui insertando." Pérez, August 2011 email. [⤒]

- I am grateful to Arte Público for sending Pérez's manuscript to me on which they based the published Spanish edition. By comparing the two, I noted changes in spelling, verb tenses, vocabulary, word usage, sentence structure, and paragraphing. [⤒]

- Reavis made copies of the manuscripts and mailed them to me. [⤒]

- The migrant stream today is even more complicated and varied: by sending nations (not only Mexico but also uatemala, Honduras, El Salvador), by gender and age (women and children) and by status (unaccompanied minors), as people flee violence, corruption, drug cartels. [⤒]

- "Como era natural, yo también quería probar mi suerte. Quería ganar dólares, de ser posible los suficientes para mejorar la maquinaria de nuestro pequeño taller. Diario, 7. ("It was natural for me to want to try my luck at earning dollars, and maybe earn enough to improve the machinery in our little carpentry shop.") (13-14.) [⤒]

- Diario 109; Diary 86. [⤒]

- Diario, 224. Literally "folding the spine." [⤒]

- Pérez writes about his experiences in the Chinese restaurant in "Stranger in a Strange Land" (Tables, [August 1986], 26-27 ; 30-31). [⤒]

- It also established employer sanctions against those who hired undocumented labor. [⤒]

- Diario, 4. [⤒]

- Diary 10. [⤒]

- ". . .me atrevería a afirmar que somos una comunidad de mojados" and "[d]esde hace varias décadas, Macuiltianguis. . .se ha convertido en un pueblo de emigrantes; se han dispersado como las raíces de un árbol que se extiende abriéndose lugar bajo la tierra para encontrar cómo alimentar su cuerpo." Pérez, Diario, 6. ("One could even say that we're a village of wetbacks. For several decades, Macuiltanguis. . . has been an emigrant village, and our people have spread out like the roots of a tree under the earth. Reavis, Diary, 12). [⤒]

- The US-Mexico Farm Labor Agreement or Bracero Program (1942-1964). Arte Público followed Pérez's arrangement and inserted the passage into Diario's chapter 3 "El Fugitivo." [⤒]

- "'That, you should write, That, you should write,' until I finished my story." [⤒]

- Video Xalapa 2011. [⤒]

- Diary, 20. "Me contó que había sido vendedor de tacos en la delegación de Xochimilco en la ciudad de México y que de ahí provenía su sobrenombre." Diario 14. [⤒]

- Diary, 16."Les llamaban de esa manera porque siempre andaban corriendo detrás de los viajeros sospechosos que se dirigían hacía el vecino país del Norte." Reavis titled the chapter of Xochimilco's story "The Runner." Arte Público titled the same chapter "El Fugitivo." I think Reavis's title more accurate since "El Fugitivo" might encompass both Xochimilco and Pérez. [⤒]

- "para el mejor y más pesado de los coyotes de Nuevo Laredo. El más pesado." He repeats "el más pesado," slang for "the most important or cunning" coyote to emphasize his importance. Diario 10. [⤒]

- Chivos and pollitos are among the plethora of slang terminology for helpless mojados subject to a coyote's whims. [⤒]

- Reavis, Diary, 55. See Sánchez-Prado for an extensive look at the publishing industry's commodification of migrants. [⤒]

- Reavis, Diary, 55. "'¡Ah! ¿Tú quieres que te invente uno?'" Diario 65. [⤒]

- Reavis, Diary, 55. "No expedida por el Gobierno de los Estados Unidos. / No se intenta causar daño alguno o fraude en contra de cualquier ciudad, compañía, o persona." Diario 65. [⤒]

- Reavis, Video Xalapa 2011. [⤒]

- "Cuando los descifré, no me sentí tan orgulloso como al principio." Pérez, Diario, 66. [⤒]

- Reavis, Diary, 70. See Sánchez 121-25. [⤒]

- Reavis, Diary, 70. "'¿Es verdad que aquí ayudan a los mojados?' — le pregunté." Pérez, Diario 87. [⤒]

- Reavis , Diary, 72. "'Perdón—dije, dirigiéndome a ella--. 'Es aquí donde ayudan a los mojados?'" Diario

,88-89. [⤒] - Reavis, Diary, 72. [⤒]

- Phone interview by Marta Sánchez Jan 2021. [⤒]

- These are the Mexican corridos (ballads), Manuel Gamio's Life Story of the Mexican Immigrant, Luis Spota's novel Murieron a mitad del río, and Daniel Venegas Las aventuras de Don Chipote, o cuando los pericos mamen The Adventures of Don Chipote or, When Parrots Breast-Feed. The Mexican corridos occupy a rich niche in the still-living oral tradition of poetic narratives in first person by migrants themselves, from "El lavaplatos" ("The dishwasher"), an early 20th century touchstone corrido expressing discontents and lamenting the incongruities between high expectations and the harsh realities of immigration, to the 1990s corrido, "Las Dos Patrias," sung by Los Tigres del Norte (Weber 23), reacting against the stigma of "traitor" Mexicans attributed to migrants. In the 1920s, Gamio's assistant interviewed Mexican migrants in the US and used their words to transcribe their voices (See Devra Weber, "Introducción," El Inmigrante mexicano, La historia de su vida: Entrevistas completas 1926-1927. Devra Weber, Roberto Melville, Juan Vicente Palerm, compiladores. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa,, CIESAS/UC MEXUS, 2002, 55. Spota, a Mexican journalist-author, lived the life of a mojado to prepare to write his novel. Venegas's parody was first published in 1928 by El heraldo de México, a Spanish-language daily newspaper in Los Angeles (Kanellos 2000). [⤒]

- "A Guide to the Dick J. Reavis Papers, ca. 1956-2007." The Wittliff Collections, Texas State University. [⤒]

- Texas Monthly was sold to Gulf Publishing Co. of Houston, making the book's publication unlikely. [⤒]