Issue 9: Editing American Literature

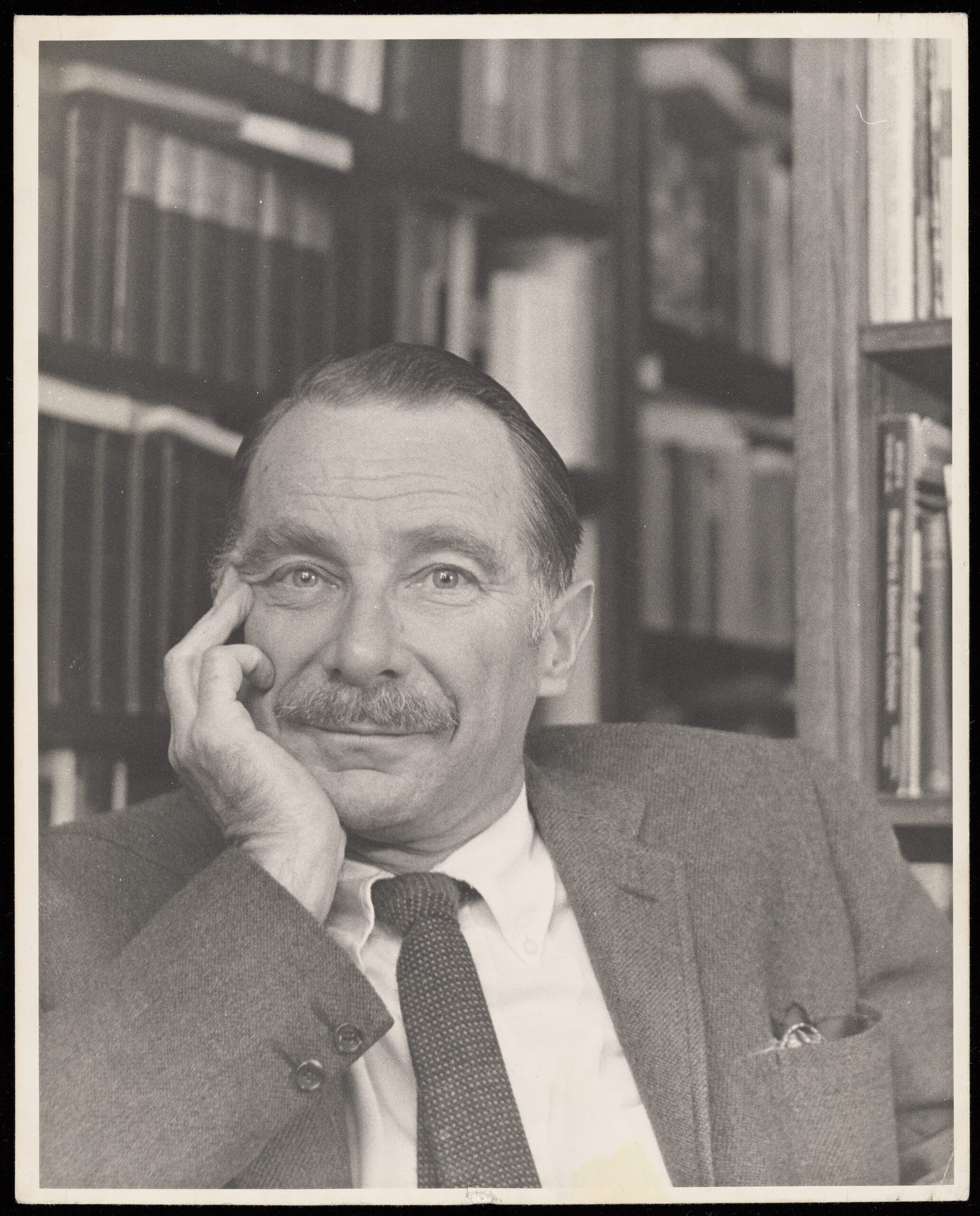

I would start out this essay with "Norman Holmes Pearson is best known as...," but Norman Holmes Pearson isn't particularly well-known as anything. For scholars of twentieth-century American literature, he surfaces in correspondence and acknowledgements here and there, or as a vaguely recognizable mustachioed face in black-and-white photos. Those familiar with the American poet H.D. likely know that Pearson represented her literary and legal interests in the U.S. after World War II. Spy geeks will recognize him as the high-ranking Office of Strategic Services (OSS) counterintelligence officer who brought his Yale student James Angleton into the espionage business during the war, and who later recruited other Yale men into the CIA. Used-bookstore rats might recall him as one of the editors of the popular 1938 Oxford Anthology of American Literature. When he surfaces, it is in the margins of better-known people's stories.

But Pearson was in fact an enormously significant figure in American literary modernism. He wasn't a poet or a novelist or a playwright, though, or an influential critic. Instead, he made his impact on modernism by shaping its texts and, even more importantly, the resources readers used to understand them. And he did this through the institutions that control and condition how artistic production reaches audiences: publishers, universities, libraries, foundations, professional and honorary organizations, and social networks. Pearson was one of the men (they were almost entirely men) who did the largely invisible work of keeping that system running, using his positions within these networks to write the story of American literary modernism and to imbue it with cultural legitimacy and prestige. Through this work, he helped manage what scholar James English has called the "economy of prestige": the distribution of status, institutional support, and awards to students, scholars, and writers who would in turn shape elite American culture.1 He was, deeply and fundamentally, an Organization Man in a time of organization men.

Pearson's faith in institutions and skill at working through them meshed perfectly with the political and social order that emerged in the U.S. just after World War II. In his influential The Vital Center (1947), historian Arthur M. Schlesinger asserted that America's political and social order was grounded on a particular notion of "freedom" defined by liberal individualism, democratic governance, and moderately regulated capitalism; by rejecting "extreme ideologies" such as communism, fascism, monarchism, and theocracy; and by embracing pragmatism and realism. This social order was overseen by an interlocking set of governmental, philanthropic, corporate, religious, and educational institutions led by disinterested technocrats who were disproportionately drawn from the elite.2 Schlesinger's book elucidated the loose postwar consensus that had arisen among the most powerful institutions in American society — government, academia, business, labor, the military, print and broadcast media, museums, mainstream religious organizations, foundations. A Mayflower descendant and son of a small-town businessman, Pearson had by the time he was forty ensconced himself in many of these institutions, from Yale University to the OSS and CIA to the Department of State to Oxford University Press.

And these American institutions were cautiously ready to accept modernism, or at least a version of it. In the U.S., the public image of modernist art and literature — epitomized by the sneering press coverage of the 1913 "Armory Show" in New York — had long been bohemianism, political radicalism, incomprehensibility, and above all foreignness.3 But in the 1940s, critics and journalists and professors and editors and curators and government officials began to redefine the terms by which modernism was understood. According to this new framing, modernism was about style and technique, not antinomianism; it embraced the Machine Age's aesthetics of streamlining and abstraction; and it employed new discoveries in psychology and the science of perception. Rather than seeking to undermine bourgeois culture, it could in fact decorate it. And most importantly, modernism's valorization of individualism, experimentation, and freedom rhymed perfectly with the values the West had defended against the Nazis, and was now defending in the Cold War.4

Pearson was not entirely on board with this "Cold War modernism" and rejected the aesthetic formalism that typified it. Yet he agreed that modernism was not a break from the American literary line but rather a natural continuation of the tradition of self-criticism and self-examination established by earlier writers like Hawthorne, Whitman, and Wharton. Scholars such as Annette Debo and Donna Hollenberg have described how Pearson promoted a particular vision of modernism that diverged from the T.S. Eliot-centric understanding dominant at the time and that put women (above all H.D.) at the center.5 But he made his idiosyncratic arguments about modernism not through criticism but through institutions: Pearson collected the works and papers of the writers he favored for Yale's Collection of American Literature, making them available for research and critical study. He then mounted exhibitions of these materials at venues like Yale's Sterling Library and the Grolier Club in New York, presenting these writers and their works as significant. He secured grants and prizes for them from foundations and honorary societies. He was among the first to teach their works in undergraduate and graduate classes. He gave personal support and assistance to young scholars whose careers would center on those writers. And he edited their works.

"Editing," of course, has several meanings, and in his career Pearson engaged in three different kinds of editing. He was an expert scholarly editor, primarily of Hawthorne. "Scholarly editing" involves identifying the optimal "copy-text" for a particular work, documenting variants between texts, and glossing references or historical context in order to produce a definitive edition. But even as he was conducting scholarly editing on Hawthorne, he was engaging in another type of editing: the selection of texts for a general reader's anthology. In 1935, when Pearson was only twenty-six, his Yale mentor Stanley T. Williams hired him to assist with the Oxford Anthology of American Literature, intended to be a definitive collection at a time when American literature had only recently come to be considered worthy of study. Finally, for a few major modernist poets such as Ezra Pound and H.D., Pearson did a little of what most people think of when they hear the word "editing" — that is, actually line-editing and proofreading. But in all of these types of editing, Pearson quietly and very much behind the scenes argued for a particular genealogy and understanding of American modernist writing, one rooted in the short-lived "Imagist" movement of which Pound, H.D., and William Carlos Williams were key members.

His taste for these poets developed early. In an otherwise conventional high-school English essay from 1927, he praised contemporary poetry and free verse in particular, citing Frost, Edwin Arlington Robinson, Vachel Lindsay, Louis Untermeyer, Amy Lowell, and — in his first recorded mention of the woman who would play such an outsized role in his life — Hilda Doolittle. As a Yale freshman, Pearson devoured Mark Van Doren's Anthology of World Poetry, in which (in the words of Robin Winks) he "encountered the world's range of poetic expression — translations from the Chinese, Sanskrit, Hebrew, Greek, Russian.... Emerson, Longfellow, Poe, Whitman were there of course, but so were poets that had not been taught, even at Andover: Ezra Pound and H.D."6

Pearson was especially drawn to Pound and H.D. because they epitomized his ideas about modernism, particularly how its poets used image and metaphor to counteract the dissociation of language and world that he saw as the predicament of the twentieth century. As he wrote in a 1949 essay, words attempt to point to a concrete and unchanging reality that modern science has shown to be radically unstable and contingent, so meaning must combine words and imagination to "impinge ... directly on the senses of the reader and become ... a stimulus to knowledge." "If science took away from the poet of our century a complete reliance on the individual meaning of words," Pearson explained, "the loss only served to emphasize to the poet the vital importance and validity of the structured image. H.D. and Pound were reacting to the impact of science in the precision of their descriptions, but they were doing it in the way characteristic of poets."7

For Pearson, then, modernist art in general, and Imagist poetry in particular, sought to reconcile a world broken apart by the modern age. Ironically, Pearson here diverges markedly not only from Cold War modernists but from the most prominent of the modernist poets, Eliot. In his essay "The Metaphysical Poets," Eliot diagnosed a "dissociation of sensibility" beginning just after the Elizabethan period, when thought and emotion — which according to Eliot the great poets of the premodern era had known as one integrated complex — came to be experienced and expressed separately. That "dissociation" had only deepened with time, to such a degree that in the modern era all we have (and all we are) are fragments, yearning for a wholeness that will never return.

Pearson agreed with Eliot that the seemingly natural relationship between time, the material world, and the language we use to describe them had been radically disrupted in the modern era. But Pearson saw in Imagism a reintegration of these now alienated aspects of consciousness. Metaphors and images didn't require the rational, empirical Enlightenment assumptions that the modern era had shattered, which made Imagist poetry "a religious and philosophical act as well as an aesthetic achievement."8 This fragmented era required someone who could reconcile the magisteria of the "scientist and the poet," the creative and the rational. The modernist poet "has been the preserver of the Renaissance heritage. In his concept of total reality he has accepted what science has taught about this newest of new worlds, but in presenting it as a work of art he has encompassed an even wider sphere."9 Pearson's mysticism here couldn't be further from the high-cultural, consumption-friendly model characteristic of Cold War modernism.

But crucially, Pearson also saw in modernist poetry a valorization of the individual, which amounted to an affirmation of the values of the West. "If we look at the psychological history of twentieth-century America," Pearson wrote, "it has been the poet who ... has made the strongest public stand for the dignity and freedom of the individual."10 Modernist literature had long celebrated the individual, especially against an oppressive or philistine society. This exaltation of the individual gained a political inflection in the 1930s, when both fascism and communism insisted that the collective — the state, or the party, or the people — was supreme. In the U.S. and the U.K., the struggle against fascism was often figured as a defense of the individual against the faceless forces of Nazism. Early Cold War rhetoric leaned heavily on this polarity, even as the enemy changed. Modernist poetry, then, stood for the reintegration of consciousness, for the "Renaissance heritage," for the creation and maintenance of community (not collectivism), and for the fundamental importance of the individual: that is, for all of the values the West was purportedly defending in both World War II and the Cold War. And even though their work might seem like an utter rejection of the tradition that Hawthorne represented, Pearson saw the American modernists carrying forth Hawthorne's project of moving American literature away from its English roots and toward an embrace of the New World.

Pearson used his editorial work to subtly assert the crucial Americanness of modernism. He had, at the beginning of his career, identified a tetrad, which for a few months in early-twentieth-century Philadelphia had been a close-knit clique, as the progenitors of modern American literature. "No group in America's literary history," Pearson wrote in the anthology, "has proved so significant as that in which ... Ezra Pound, Hilda Doolittle, William Carlos Williams, and Marianne Moore moved as friends."11 He wanted to reconfigure American literary history around them — and Pound in particular — and in so doing claim that international modernism carried more American genes than anyone had previously granted. He drew upon his particular skills as a networker and a creature of institutions to accomplish this. H.D. and Pound needed things from him, things that because of his connections and skillful networking he could deliver. His work for these two poets included not just editing proper, the focus of this essay, but collecting, teaching, funding, obtaining prizes and positions for, fostering scholarship on, and even acting as a legal executor for them and their works: in the aggregate, acting as a kind of "agent" for them, in the most expansive sense of the term. (He tried, as well, to serve the same role for the other half of the tetrad, but Marianne Moore largely resisted his advances, and New Directions Books publisher James Laughlin was already filling the "admirer/fixer/editor" role for Williams.) These wide-ranging and ultimately consequential efforts for Pound and H.D. epitomize his deliberate, institutionally grounded approach to advancing public understanding and acceptance of modernist literature, and thus underscore how these institutions, not the self-evident brilliance of the writing itself, thrust modernism into the mainstream of the American literary tradition.

Pearson's personality and institutional orientation led him to excel not just as a literary "agent" but as an espionage agent. A sickly and disabled boy due to a childhood injury, early on he learned that to succeed in life he needed to make himself into a miniature adult, a builder of networks and a joiner of clubs and institutions. This gave him the security and stability that he craved when he couldn't be athletic. Soon after he was recruited into the OSS in late 1942, his obvious skills as a networker spurred his superiors to quickly move him out of the Washington-based Research & Analysis branch — the so-called "Chairborne Division" in which so many Ivy League professors worked — and put him on a four-person team charged with creating a counterintelligence branch. During the war, Pearson not only built the counterespionage structure that enabled the Allies to completely neuter the German spy apparatus in Britain but also created the curriculum of counterintelligence training that the CIA would use in its first decade. (Turning down offers to work for the Agency after its creation in 1947, he then acted as a CIA recruiter at Yale through the 1950s and perhaps afterward). His exquisitely developed skills for cultivating people — working behind the scenes to help them get what they want from institutions, which in turn solidified his own position within those institutions — gave him the status that he would use to benefit not just modernist writers but also his friends, his department, his scholarly field (American Studies), and even his nation during the 1950s and 1960s, when he traveled abroad extensively as a cultural diplomat. He was truly an "agent" in every sense of the word, acting on behalf of his poets, his profession (he was one of the leaders of the discipline of American Studies in its early decades), his university, and his nation, and rarely wanting to call attention to himself because he knew he was most effective working behind the scenes, quietly pulling the strings of influence.

Pearson's editing career began early. His dissertation (started in 1935, completed in 1941) was a scholarly edition of Hawthorne's French and Italian Notebooks. While working on that, he also contributed to Randall Stewart and Stanley T. Williams's edition of Hawthorne's complete correspondence (a project he eventually headed, though it remained incomplete at his death in 1975). In 1937, Pearson edited the Modern Library's Complete Novels and Selected Tales of Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of the first "Modern Library Giant" titles, choosing which public-domain works to be included and writing the volume's introduction.

But in terms of modernism, his first foray into editing was the Oxford Anthology with Williams and Saturday Review of Literature editor William Rose Benét. At first, Pearson had helped Williams select passages from American prose writers and written some biographical sketches, but after Williams dropped out due to his involvement in a competing project, Pearson made the majority of those selections and produced all of the capsule biographies. Initially, Benét was in charge of choosing poems, but after Williams and Pearson complained that he wanted to include something from just about everyone he'd ever met or published, Oxford University Press's American head, Howard Lowry, put Pearson in charge of that as well.12 Benét's fulsome choices had also reflected the Review's middlebrowism, and while Pearson admitted that he hadn't included as much "technically radical" work as he would have wanted, the anthology that resulted is still notable for its modernity: it was the only collection of American literature published during the period 1934-41 to include key modern poets John Crowe Ransom, Allen Tate, Hart Crane, e.e. cummings, Gertrude Stein, Wallace Stevens, Marianne Moore, William Carlos Williams, and H.D.13 The Oxford Anthology, Pearson said proudly in 1969, "was the first really to give equal prominence to twentieth-century American writers in comparison with the established nineteenth-century reputations."14

The product was important — the Oxford brand gave cultural legitimacy to American writers in general and especially to the modernists — but, for Pearson, the process was even more so. Benét tasked him with contacting the dozens of living writers for a short explanatory note about their techniques and for permission to reprint their works. It's no exaggeration to say that these clerical tasks were the most personally consequential work Pearson ever did. They put this ambitious grad student in the middle of the contemporary literary scene, and the resulting acquaintances enabled almost everything he did in that world later in his life. Moreover, those endless form letters led to dozens of close personal relationships. Some, as with H.D. and Horace Gregory and John Gould Fletcher, evolved into the most important friendships of his life. Others — with Pound, Williams, Moore, Wallace Stevens, Gertrude Stein, Thomas Wolfe, and many others — became the connections that allowed him to forge his singular career.

Pearson initially "met" Pound only through the mail, asking to include his Imagist manifesto "A Retrospect" and imploring him to write "another brief section [regarding] the technical problems behind the writing of the Cantos."15 (Unsurprisingly, Pound declined to explain his method.) Pearson re-established contact soon after Pound was returned to the U.S. and held at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington DC, writing Dorothy Pound to offer his assistance on Pound's defense committee, and suggesting that Yale might be able to help the poet financially by purchasing any papers the Pounds might want to sell. Two years later, in 1949, the already overworked Pearson reluctantly agreed to type up Pound's translation of the Analects of Confucius, one of the projects he had been working on while detained in Italy. (The Pounds were remarkably ungracious, griping to Pearson about how long it was taking him to finish the job.16)

This Analects translation appeared in the Hudson Review in 1950, and then, in 1951, as the second book in the "Square Dollar Series," a short-lived paperback publishing venture run by two far-right activists, John Kasper and T. David Horton, at Pound's direction. Square Dollar was Pound's attempt to get texts from his alternative economic, historical, and literary canon into the college classroom. The problem was that Pound loathed the academy and especially professional literary scholars (or "commahunters" as he often called them), mostly because he had found the philological work he was expected to do in graduate school pointless and deadly to literature's vitality. So to reach the academic audience that Pound had always excoriated, Kasper and Horton assembled a board of university-professor "advisory editors" who would "make suggestions, esp. of titles for publication." In mid-1951, James Craig La Drière of The Catholic University of America reached out to Pearson to invite him to be on this committee, along with Marshall McLuhan of the University of Toronto and several others.17

Pearson tried to keep Kasper and Horton at arm's length, and he saw his involvement with the series mostly as a favor to (and means to maintain a connection with) Pound, but Kasper took his job as publisher seriously. He prodded Pearson in 1952 that

the best ground-work accomplished thus far toward getting Square Dollar in the curriculum has come from persons NOT of the advisory committee. Hugh Kenner, Charles Olson, and William D. Hull have all placed Fenollosa and Pound's Analects in their classroom. And certainly Dr Pearson is not one to allow the 'utter and abject farce' of the American university to continue, is he?18

Pearson confided to Pound that while he did assign the Square Dollar books to his students, Kasper and Horton weren't particularly reliable on the distribution side of things "because of the twins' other jobs."19 (Kasper ran a bookstore in Washington and became active in the pro-segregation movement after Brown v. Board of Education, and Horton was working part-time in Washington with a far-right group called "Defenders of the American Constitution.")

As Alec Marsh shows in a recent study, Pound and Kasper were in a fully symbiotic relationship by this time, with Pound's anti-Semitism and Kasper's white supremacy converging and feeding each other, and both tried to pull Pearson into their activities.20 Never particularly previously interested in questions of the legal and social issues relating to African Americans, segregation, and Jim Crow, Pound came around to Kasper's argument that the Constitution and the 14th Amendment implicitly mandated racial segregation, and Kasper eagerly adopted Pound's anti-Semitic ideas about sovereignty, national control over the money supply, and Jewish bankers. In mid-1956, Kasper formed the "Seaboard White Citizens' Council" with the motto "Honor-Pride-Fight: Save the White," and he traveled to Clinton, Tennessee, to organize resistance to the integration of the public schools there. Pound reported this coyly to Pearson: "the excited Kasper off on something ... superficially geared to local excitements."21 Through the rest of 1956 and 1957, Kasper traveled throughout the South agitating against integration and was a suspect in several bombings. He was acquitted of charges of sedition and inciting riot in Nov. 1956, but national press coverage identified him as a disciple of Pound's, complicating the campaign to get Pound released from St. Elizabeths. (Later, Kasper served two short prison terms.)

For his part, Pound was delighted that Kasper was preaching the Poundian gospel, but he was careful to maintain some distance and deniability. "He is not acting on my orders, nor did he consult me / BUT I do not judge discretion of men acting in places I have never been," he archly told Pearson.22 He sent Pearson copies of Kasper's newspaper, the Clinton-Knox County Stars and Bars, and other racist material. Pearson kept his distance and tried to change the subject: "What the hell is he doing down there? Much better if he'd keep to Square Buck series ..., or to bookstore and pay me back the twenty bucks he still owes me."23 A year later, he confronted Pound more directly on this: "Still can raise no enthusiasm for Kasper's rant. Can only see harm in what he tries to do ... Wish I could sense what you feel good in his rabbling."24 But Pound wasn't dissuaded, and took the opportunity to decry race-mixing: "The dance from the beginning of time: courtship toward copulation / Now Elvis Rock an Roll / ... do none of our obviously god DAMNED contemporaries ever notice anything."25

Fortunately, they didn't only correspond about the Square Dollar series or racist politics in these years. A teacher by vocation and an editor by both experience and temperament, Pearson combined the two professions in the early 1950s, when he started teaching a graduate seminar on Pound and the Cantos. (Pearson was always one of the most popular teachers at Yale, but in Fall 1953 this grad seminar on one of the most difficult poems imaginable enrolled 28, including students from the medical and engineering schools!26) "Wish there was something special to say about the way I teach Pound in the graduate seminar," he wrote when asked how such a class could draw so many students, "but he makes such an open-door into the 20th-century, that almost anything is possible, and I work according to the knowledge of students and their interests. The best I can say is that it works."27 For their term project —interpreting and glossing all of the references in a single Canto—most students turned in five- or six-page papers, but in 1952 the overachieving future journalist Tom Wolfe produced 105 pages on Canto XLVII!28 Pearson then compiled and mimeographed these student projects and distributed this samizdat reader's guide among members of the small but growing network of Pound teachers and scholars.

With the blessing of Pound and his publisher James Laughlin, Pearson also enlisted students in the task of correcting the text of The Cantos, mostly by noting inconsistencies, errors, and misspellings. "When [the students] are finished Ezra has agreed to work out with me a truly definitive text for the Cantos," Pearson told Laughlin in 1953.29 Although Pearson and his students embarked on this project because "it had to be done, and done with Pound's cooperation," Pound wasn't always particularly helpful in this "commahunting" work: he "blows hot and cold" on the corrections, Pearson noted, because he was so consumed with writing the current ones.30 Pound did, though, immortalize Pearson in the poem. Pearson had visited Istanbul with H.D.'s partner Bryher in November 1954, and his casual remark to Pound about Istanbul's Hagia Sophia appears in Canto 96: "'vurry,' said Pearson, N.H., 'in'erestin'.'"

At the same time, Pearson was helping the Berkeley graduate student John Edwards with his Preliminary Checklist to the Writings of Ezra Pound, one of the first scholarly projects on Pound. A collector like Pearson, Edwards based his Checklist heavily on his own rare editions of Pound's works—necessary, because in the 1950s no libraries were systematically collecting those materials. Pearson counseled Edwards not only on the scholarly work but even on how to print, distribute, and price the book, which eventually was published by an independent bookstore-cum-printer in New Haven.31

Throughout the 1950s, Pound and Pearson kept up a sporadic correspondence, focused partially on the editing work and partially on politics, and Pearson visited him twice in St. Elizabeths — in December 1952 and March 1958. As Pound and his paramour Marcella Spann started to compile the literary anthology Confucius to Cummings (what Pound called the "Spannthology"), he mailed Pearson, embedded within his imperious ramblings, wish-lists of poems to retrieve from the Yale library. For those who've read Pound's correspondence, particularly after the 1920s, his letters to Pearson are a very typical example of the genre: commandeering rants about writers that one must read and pet theories that rarely engage with the questions that the interlocutor is posing, some typed but many scrawled in pencil, with idiosyncratic spellings and capitalizations. Pearson, working on his editing of the Cantos, gamely attempted to redirect Pound and get information from him about how he intended to format the lineation of a section or whether the spelling of a name is correct, but Pound rarely answered and is instead off on a pet obsession.

When he did respond to Pound's accusatory questions about politics, Pearson's responses looked like missives from an entirely different planet: his establishmentarian New England Republican world. He was cautiously enthusiastic about Eisenhower's election in 1952 because it would bring about a "revolution" — specifically, a

revolution in the managerial sense .... That is, the appointment of men who theoretically at least do know management; now we can see whether their kind of management can be turned over to govt .... I remember during the war being criticized by some big shots as being too 'professional.' But I don't admire the amateur per se in anything, whether in writing or statesmanship.32

Pearson's enthusiasm about managerial expertise epitomizes the postwar managerial and professional order that he himself embodied. Broad institutions staffed by trained professionals and technocrats would lead America into its new age of Cold War responsibility. But it's hard to think of anything that would put Pound off more than this faith in bureaucrats and dismissal of uncredentialled amateurs. Pearson didn't like Sen. Joseph McCarthy because he was a populist and an ignoramus; Pound, a passionate anti-Communist with a soft spot for demagogues, found him curiously appealing. Pearson warned Pound away from the young poet and conservative thinker Peter Viereck for being a suck-up and "unclean physically as well as spiritually"; Pound liked Viereck's articulation of a conservatism grounded in "rooted liberty" and the "organic unity" of a people.33 (In fact, in Pound's and Pearson's political discussions there are prefigurations of the current internal Republican Party conflict between conspiratorial populists and institutionalists. Perhaps the most surprising thing here is that the Poundian conspiracists and demagogues have come to hold the upper hand in the party, which would have been unthinkable in the 1950s.)

But like so many of Pound's disciples and admirers, Pearson did adopt Poundian voices and locutions when writing to him. When Pound demanded to know "what did you LEARN while in the 'intelligence' (end quote) service?" Pearson's response was cringeworthy:

What did I learn in the 'intellidunce' service? Waal, it warn't really that. My job was counter-'intelligence' (end quote), a task made much easier by the lack of such intelligence on the part of all services—German, wop, frog, eyetalian, usa, etc... what did I learn? That nobody knows a half of what they think they do, and what they know ain't wuth knowing.34

What seems initially like an embarrassing attempt by Pearson to mimic his master, though, is something much more telling about how Pearson moved through his institutions and circles, omnipresent and affable but never really standing out. He sidesteps here; he never answers the question directly because his intelligence work was still secret, and he may have still been doing it at some level. "Once an agent, always an agent — for someone," Pearson once gnomically said about himself. Deflect, redirect, and flatter: like a good spy, keep the focus on your target, and keep him talking. In another letter, responding to Pound's desire for Pearson to place one of his poems in a top literary journal, Pearson offhandedly mentions that "a couple of ex-students" of his are on the staff of The Paris Review.35 One of those students was the writer Peter Matthiessen, who was also working for the CIA at the time because Pearson had recruited him into the Agency.36

Ultimately, Pearson's actual editorial work for Pound was relatively minor; his collecting and teaching were far more consequential in building the poet's postwar reputation. This was not true for his work on the behalf of H.D., who had been intimately connected to Pound, both personally and artistically, since she was a teenager. Less than a year apart in age, they met in 1901, when she was only fifteen and he a student at Penn. They were "intermittently engaged ... for several years" afterward.37 He encouraged her writing and gave her the name "H.D." when putting together the first Imagist anthology in 1914. Ultimately, the engagement fell through, and the two married other people, but the Pounds lived across the hall from H.D. and her husband Richard Aldington in London until both Pound and H.D. left England — Pound for Italy, and H.D. for Switzerland with her lover Winifred Ellerman, who called herself Bryher. Both were American expatriates, bohemians, modernist poets obsessed with Greek mythology, and both stayed keenly interested in each other even as their lives diverged dramatically. During the war, Pound made propaganda broadcasts for Fascist radio even as H.D. endured the Nazi bombing of her London neighborhood.

Pearson met H.D. at the same time, and in the same way, that he met Pound: through the Oxford anthology. H.D. and Bryher came often to the U.S., and Pearson saw them twice in 1937. Pearson was in awe of H.D. — he thought she was one of the greatest living American poets — and clicked immediately with Bryher, whose independence, patrician bohemianism, and compulsion to be in constant motion he greatly admired. During the war, when Pearson and the two women were all living in London, their connection deepened, and they would remain close for the rest of their lives. H.D.'s biological daughter (and Bryher's adopted daughter) Perdita Aldington called them a "cerebral ménage à trois."38 They even had pet names for each other: Bryher was "Fido," and after Pearson was named a chevalier in the French Légion d'honneur in 1950 for his war service, H.D. called him, half seriously and half ironically, "Chevalier." After the war, and especially after H.D.'s death in 1961, Bryher and Pearson developed what was perhaps the closest relationship in either of their lives. They exchanged daily letters for many years in which they shared their experiences, their devotion to promoting H.D.'s work, and their similar politics. (Ironically for such a bohemian, Bryher was a diehard Tory, Churchill worshiper, and loather of anything that smelled of socialism.)

When the war began, H.D. empowered Marianne Moore as her literary agent in the U.S., but soon after Pearson arrived in London in 1943 he was advising her on publishing and promotion. When Oxford published her The Walls Do Not Fall in the U.K in 1944, Pearson used his connections with their New York office to ensure that it would appear in the U.S. as well, and his blurb for the book identified him as the editor of Oxford's popular anthology.39 She sent him poems from the second part of her wartime trilogy, Tribute to the Angels, and he counseled her that although "the tone is right and the feeling is as sure as ever" it would probably be wisest until she completed the trilogy to publish it. (She did not heed this advice, and it came out in 1945.) In 1946, she dedicated the third section, The Flowering of the Rod, to him. "It is my greatest honor from the war," he told her. "No medal, nothing can compare to the pride I feel in seeing my name in it ... it gains even a new height in your poetry, so precise and meticulous, so beautifully controlled, so exquisitely and naturally formed.... Now I am only anxious," he said, thinking less like a business representative and more like a literary agent, "to have the three parts appear together."40 He was annoyed, though, that Oxford simply exported to the U.S. its British printings of Flowering in cheap wartime paper wrappers with the original price of three shillings and sixpence visible, along with the marked-up American price of $2 (a price typical for a nice hardcover at the time): "mind you," he reported to H.D., "I don't mean that a volume of your poems isn't worth two dollars; it is only because with the paper binding and the English price on the back it may lose something for gift sales in favor of the better format of other volumes of poetry."41

In December 1945, H.D. transferred her U.S. power of attorney to Pearson "until I am able to cross [the Atlantic] myself."42 But she would not return to the U.S. anytime soon. Immediately after the war, in a Swiss clinic recovering from meningitis (exacerbated by malnutrition during the war) and a nervous breakdown, the poet fully entrusted Pearson with all of her literary affairs in the U.S., telling him to "just go ahead as YOU THINK BEST."43 She trusted him so much that she even transferred to him the copyrights to her American publications because "it was infinitely simpler for me to own the copyrights and to make her a gift of whatever earnings came in from them" than to file semiannual tax reports to the British government, Pearson explained later.44

As her agent, Pearson's primary goal was to help H.D. gain a reputation as one of the central modernist poets. To do this, he needed readers to see that she hadn't stopped writing in 1914, and that her later work was superior to her well-known early poetry. "My chief aim," he explained to the poet Horace Gregory, a close friend of both of them, "is to rid the public of the idea that H.D. is dead, or ... a period piece. She has been praised so much as the poet who was loyal to the Imagist tenets that it has turned into no praise at all."45 Almost immediately, he began approaching publishers with the work she had produced during the war. "Any time you want to send a batch of mss over, do so by all means, and I will do my best with it," he told her.46

The problem was that others didn't share his high opinion of H.D.'s work, and thought that she was indeed a "period piece." Evaluating her memoir of being treated by Freud, Kurt Wolff of Pantheon Books bluntly identified the obstacle confronting Pearson:

If the author were a well-known personality in the U.S. some people would be interested in her personal experience, but in view of the fact that only a very limited number of people are interested in H.D.'s poetry I am afraid that we would not find a large enough audience to even so much as break even with the publication costs.47

By making available more of her work — not just her poetry but her fiction and her memoirs — Pearson sought to turn her into, if not precisely a "well-known personality," then someone whose readership was not so "very limited."

Over the course of the 1940s he sent out the Freud manuscript and many others to numerous publishers. Many passed them up; eventually, some bit, even if the publication arrangements weren't above board in all cases. In 1948, Gregory privately encouraged Pearson to submit By Avon River, H.D.'s multigenre meditation on Shakespeare, to Macmillan, knowing that the publisher would ask him (Gregory) to review the submission and decide whether to recommend publication.48 (He did, and they did.) As Pearson started to place manuscripts with publishers, his role expanded beyond agent to editor, and H.D. came to trust him alone to edit her work. After he told her that Macmillan had accepted Avon River, Norm assured her that only he would handle edits: "Horace's part is over with having read the manuscript for the publishers, and all communications about the book will be with me. And I will make no changes without consulting you." Some months later, putting on his scholar hat, he submitted to her an extensive list of queries and corrections regarding dates, spellings, accurate quotations, and even commas. Nowhere, though, does he make any suggestions about the substance of her writing: this was not the kind of editor he understood himself to be.49 With no small degree of chutzpah, after publication he tried to arrange for Gregory's wife, the poet Marya Zaturenska, to review the book for the New York Herald Tribune.

In terms of establishing H.D.'s literary reputation, Pearson's most significant single accomplishment was editing and finding a publisher for her Selected Poems. In the 1950s, no such collection was easily available. While Boni & Liveright's 1925 Collected Poems was technically still under copyright and had been reprinted as recently as 1940, the collection didn't include any of H.D.'s work from the two decades following its first printing. This was a huge impediment to Pearson's campaign, since collected or selected editions are crucial tools in creating a poet's reputation. They signify that a poet has had a career, a body of work produced over a number of years worthy of considering in its entirety. The publication of a hardcover selected or collected edition is an argument aimed at reviewers, critics, and award committees. It is a claim: this is a major poet. Furthermore, at this time the trade paperback was just beginning to emerge, targeting the growing student market. If a hardcover Selected Poems was aimed at serious readers and elites in the literary world, a trade paperback would reach a market of young readers and students who might develop an enduring love or at least respect for her work.

Two American firms specialized in trade-paperback editions of contemporary avant-garde writers: Laughlin's New Directions and Barney Rosset's more edgy Grove Press, which counted among its authors Samuel Beckett, Allen Ginsberg, and Jack Kerouac. Pearson pitched a Selected Poems to Grove in 1956, and the publisher agreed to it. Pearson, with the assistance of Gregory and Zaturenska, chose the poems and negotiated a contract specifying simultaneous hardcover and paperback editions, the latter priced at $1.25. The total print run would be 3800, including 1300 hardbacks (fifty of which would be signed collector's editions).50

Grove's Selected Poems, which appeared in summer 1957, did its job. 2088 of the 2500 paperback copies sold in the first six months, even if those sales dropped off dramatically in the second six-month period, to nine. The hardcover sales in the same periods were, respectively, 253 and 64.51 While her work was still too experimental to win either of the year's major awards (the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize), it did urgently remind critics and readers that H.D. was still alive and writing. Pearson capitalized on the attention that H.D. received to place poems in 1957 and 1958 in three high-profile general-interest American magazines — The New Yorker, The Nation and The Atlantic Monthly —as well as in Poetry and Grove's own journal, the influential Evergreen Review.52

Frustratingly, though, Grove didn't follow the script Pearson had written for the two of them. As Pearson wrote in a 1958 letter, he was "distressed and surprised" to learn that Grove had allowed Selected Poems to go out of print in early 1958. His letter to Grove is worth quoting at length, as it demonstrates Pearson's sophisticated understanding of how publishing and publicity create literary reputations:

Word-of-mouth knowledge of the existence of Selected Poems is mounting, since reviews like the two in the January issue of Poetry have hardly had time to stimulate knowledge of its existence and quality, and because articles like Horace [Gregory]'s forthcoming one in The Commonweal should help to continue the momentum. Again, the citation of her Selected Poems in my revision of The Oxford Anthology of American Literature as the source for many of the texts will be a further advertisement.... What is important to me in the building up of H.D.'s reputation is the fact that Selected Poems should remain in print [and] with this in mind I suggested to Horace the possibility of some business arrangement between the Grove Press and myself by which republication could be ensured.53

The logrolling here, invisible to most readers, is worth bringing into view. Pearson and H.D.'s close friend Horace Gregory — whose reader's report on By Avon River for Macmillan had started the H.D. publishing revival in 1948, and who was now an editor at Grove — was reviewing the Selected Poems positively in a wide-circulation magazine. Pearson, who represented H.D.'s financial interests in the U.S., was using his position as editor of the Oxford anthology to promote sales of the Selected Poems and to provide a subsidy to Grove to ensure that the book would remain in print. As a former spymaster, Pearson was entirely comfortable with sub rosa machinations that would ultimately benefit the cause. There's not a great deal at stake in these conflicts of interest, and Pearson was not financially benefiting from this arrangement, but the ethics here do feel a bit sketchy.

In any case, Pearson's machinations worked. Only three days later, Pearson received a one-line note from Grove: "WE WILL KEEP THE SELECTED POEMS IN PRINT!" They didn't even accept the subvention he offered (although in 1963, with Grove again about to let the book go out of print, Pearson lent the company $500 to cover production costs for a new printing).54 "It is a good title to have," he assured them in 1963, "and although the sales will never be spectacular I think they will prove steady. Two books on her are now being written and these should help to continue to draw attention to her."55 In the four years after Selected Poems appeared, Grove published two other H.D. titles: Bid Me to Live in 1960 and what is often considered her masterpiece, Helen in Egypt, in 1961. In that same period, the American Academy of Arts and Letters honored H.D. with its "Award of Merit" for poetry, and the Academy of American Poets nominated her for a $5000 grant the following year. After decades on the fringes, the Selected Poems had brought her validation by elite literary institutions.

But these honors didn't culminate Pearson's campaign on H.D.'s behalf. He wanted readers to see that she was at the height of her creative powers, and that her current work was in fact her best work. Fully inhabiting the persona of the agent he had become, in early 1960 he used the AAAL's award to press Rosset to accelerate the publication and promotion of Helen in Egypt. "The Academy's award ... makes me wonder if the announcement of the publication of 'Helen' would not be appropriate," he suggested. "We could perhaps arrange also for the release of her recording of the poem before the book's actual publication, as a preliminary teaser."56

Pearson had also been involved in a small way in Helen's composition. In Switzerland in 1954, the two had extensively discussed how best to incorporate the notes and the poetry together in a published edition — what they should look like on the page. As the poem neared completion, Pearson offered his suggestions on knitting the sections together, asking (for instance) "whether Part IV (Winter Love) needs some bridging paragraph at the beginning similar to what you have written for the other three sections. But not more than an opening one I should think; for after all it is a coda."57 He would never have deigned to suggest altering anything substantive in her texts themselves, but he certainly had a great deal to do with shaping the books: what was included, how it was presented on the page, what paratextual elements framed the texts, and what audiences they were designed to reach.

Helen would be Pearson and H.D.'s last collaboration. H.D. suffered a stroke in July 1961 and her health declined rapidly. She passed away that September. Saddened at the loss of his great friend, Pearson nonetheless took comfort in the fact that his work over the last fifteen years had been successful, and that she had been able to see that success before she died. "I have tried," he told Bryher just a few weeks after H.D.'s death, "to help Hilda gain the rightful place in poetry that she deserved and that I think she so richly enjoyed at the end of her life with the prizes she got and the acclaim she had."58

But he wasn't done. Throughout the later 1960s and into the 1970s, Pearson stubbornly stuck to his strategy of deferring a full collected edition in order to showcase her later poems that, he insisted, should be published on their own, particularly because they had become so influential to contemporary poets. "The proper strategy," he told Laughlin once New Directions started to handle most of H.D.'s books in the early 1970s, "is [to] assure attention to her later period. After that a selected or collected poems might appear, and obviously should, but if this were to be done now the reviews would rely on the old clichés."59 One "old cliché" was that she was essentially a creation of the men who had surrounded her — Pound and Aldington in particular. But the much more pernicious cliché, to Pearson's mind, was the persistent reduction of H.D. to "the poet who remained true to Imagism, as though she were the Penelope," as he described it to the San Francisco poet and fervent H.D.-admirer Robert Duncan.60 Reviewers of a collected edition would "read up on the old reviews, and we'd have another 'quickie' on H.D. as the faithful Imagist."61 But readers needed to realize that rather than being a follower of Pound, she was instead a leader like Pound, with her own school of acolytes.

Pearson's initial choice to publish with Grove Press, rather than the strongly Pound-associated New Directions, helped with this. Even though Rosset used "quasi pornography as a meal ticket," Pearson told Bryher, "there is a slight value in having her poems put out by even such a shady publisher as that of Last Exit to Brooklyn, which is the implication that she is interesting to the younger people and not a memorial wreath put out by Macmillan."62 Members of the nascent counterculture loved Grove's daring books. Moreover, the first-generation modernist poets (particularly Pound, Williams, and H.D.) that Grove and New Directions published had spawned a set of anti-establishment followers and movements including the Beats, the San Francisco school, the Black Mountain school, and the New York Poets. Donald Allen's influential 1960 anthology, The New American Poetry, 1945-1960 (published, naturally, by Grove), documented this lineage.63 Grove's fortunes fell in the late 1960s, though, in part due to Rosset's poor financial decisions (including investing in real estate and pornographic films), and in the early 1970s New Directions took over publishing H.D.'s new titles and back catalog.64

As a creature of the university, Pearson knew that academic scholarship and research were increasingly pivotal in creating and sustaining literary reputations. In the mid-twentieth century, universities were only just beginning to be sites for the production and study of contemporary literature, and Pearson did more than almost anyone else to ensure that Yale would be one of the most important of such sites. He did this through teaching, acquiring authors' papers, and organizing readings. He also did this through cultivating scholarship: helping graduate students find and access materials, reading their drafts, and using his connections with journals and publishers on their behalf. He had done this as far back as 1941, in his first year on the faculty at Yale, for Robert Bartlett Haas (who was working on Gertrude Stein); he had done this for Edwards and others writing about Pound in the 1950s; and in that same decade, he started doing this for young scholars, most of them women, who were starting to write about H.D. The first such project began in 1957, when Pearson asked H.D. to correspond with a student at Indiana University in conjunction with his dissertation on her work. Five years later, Kathryn Gibbs Gibbons asked him for some archival information, and he helped her shape her article "The Art of H.D.," one of the first pieces of academic criticism on the poet, for the Mississippi Quarterly. Some years later, he worked with Susan Stanford Friedman as she completed her dissertation on H.D., giving her access to the archives he kept in his own office.65 These women and others established the field of H.D. studies and bolstered the idea that women writers were central to American modernism.

But Pearson would not live to see the most unique critical work on H.D. published. With Pearson's encouragement, in 1959 Duncan started working on an extended appreciation of his idol. Knowing the power that a statement of H.D.'s current importance by one of the best-known avant-garde poets could have, Pearson did everything he could to help: he read Duncan's drafts, gave him access to H.D.'s archival material, and even sent him two $500 personal checks. The H.D. Book, which appeared decades after both men's deaths, was a strange and capacious project that Duncan described as "a tapestry or collage book; unfolding the story of my adventure and vocation in the art; and at the same time, interwoven, imagining what another generation will have to work at."66 Pearson, though, came to regret giving Duncan unfettered access to H.D.'s papers when Duncan allowed an H.D. superfan and literary renegade named Harvey Brown to borrow her unpublished manuscript Hermetic Definition. Brown promptly produced a pirated version of it, threatening New Directions' copyright on its own forthcoming 1973 edition of that same book. Laughlin, already livid at the "anarchistic" Brown for pirating William Carlos Williams's Spring and All some years before, wanted Pearson to bring suit against him, but Pearson managed to broker an agreement that kept everyone out of court.67

For all Pearson's efforts to detach H.D. from Pound, their stories began to run parallel again after the war, when Pound was involuntarily held at St. Elizabeths and H.D., too, was hospitalized for an extended time. Both poets then entered a highly productive stage of their careers in the mid-1950s, with Pound producing three sets of Cantos (as well as other prose and editing projects) and H.D. composing Helen in Egypt and several memoirs. Their American publishers and representatives were also undertaking remarkably similar efforts on their behalfs: two-pronged campaigns both to make available their earlier writings and to showcase their new poetry. Such campaigns implicitly argued that the two poets were still vital presences, elders of the literary world.68 But while Pearson was battling H.D.'s obscurity, Laughlin had the more daunting task of neutralizing Pound's infamy.

For that reason it seems almost overdetermined that the two — the poets he admired most, and the people who had made him an influential figure in American modernism — converged in Pearson's last editorial project. After Aldington sent her a sensationalist story on the St. Elizabeths menagerie, H.D. composed a series of impressionistic sketches of Pound and her relationship to him. Pearson encouraged this. In fact, according to Hollenberg, he thought it would be "therapeutic [and] urged her to complete it despite Bryher's forceful objections." Pearson is everywhere in the memoir that H.D.'s sketches resulted in, End to Torment (a reference to Pound's impending freedom). The book is dedicated to him, and he is mentioned almost two dozen times in the short text. "Most significantly," Hollenberg continues, "[H.D.] concluded the work with a long quotation from a letter from him, an aesthetic decision that foregrounded his mediation and, at the same time, allowed her to maintain a critical distance" — and, I would add, that put Pearson, who had long stood invisibly by the side of these poets, visibly at the center of modernist literary production for the first time.69

Once it was complete, H.D. sent Pound the manuscript — he wryly deemed the title "a bit optimistic" — and then set it aside, not wanting (in Pearson's words) to "take advantage of Ezra's situation, or bring back too strong memories of Washington."70 After H.D.'s death and the publication of Helen in 1961, Pearson didn't rush to publish End to Torment. Instead, he wanted to make sure the Selected Poems remained available, and to "get into print a volume which reprints the war trilogy, the owl sequence, Sagesse, etc., which must appear separately without appearing first at the end of a Collected Poems," he told Bryher.71 And Laughlin just wanted to bury public memory of Pound's merry band of crazies and racists at St. Elizabeths. "Ezra really doesn't care too much what happens to him now," Laughlin told Pearson in 1971, but "it would be easier to 'present' this very unusual little book at a later date."72 A few years later, the two moved to get the book into print, but before he could prepare the final text, Pearson died suddenly in 1975. Michael King at the University of Texas completed the manuscript, which New Directions finally published in 1979.

Although he didn't live to see Torment published, Pearson knew by then that his work on behalf of H.D. had succeeded. Indeed, the lifelong chain smoker had lit up a metaphorical victory cigar back in 1967, writing Bryher that "at long last my campaign for her recognition is beginning to take hold, and my hunch is that she will soon be the focus of much critical attention."73 He was right: as an editor and agent and mentor, he expanded readers' understanding of H.D.'s œuvre, helped her become an icon of feminist literary studies, and contributed to establishing her position at the center of American modernism. But he hadn't done this just for H.D. By circulating his students' glosses on The Cantos, Pearson enabled professors across the nation to teach Pound in the 1950s, and his corrections and edits permitted Laughlin to publish a revised, complete version of The Cantos in 1969. Beyond H.D. and Pound, he even made the selections for New Directions' 1949 Selected Poems of William Carlos Williams — the first career-spanning collection of Williams's work.74 Perhaps most significantly, he acquired the papers of all three of these writers for Yale's Collection of American Literature.

The real product of Pearson's work for H.D., Pound, Stein, William Carlos Williams, Eugene O'Neill, and so many others not examined here was the unglamorous but essential assembly of a scholarly infrastructure. Such an infrastructure built both individual literary reputations and an alternative American modernist "canon" — one centered not on the gloomy Christianity of the then-inescapable (and not particularly American) T.S. Eliot but rather on Williams's regional rootedness; Pound's autodidactic, European-Chinese-American understanding of history; and H.D.'s Freudian hermeticism and Greek-Egyptian mystic visions. And, like the spy he once was — and, many suspect, never stopped being — he did this as an "agent" in the broadest sense of the word: one who acts, one who causes effects, one who sets things in motion even if his own traces were evanescent.

In so doing, he transformed the structures of the interlocking institutions that had become his habitat and that provided the foundation for this redefinition of modernism. At a time when elite institutions enjoyed Americans' trust more than they have in any period before or since, Pearson's extensive and carefully cultivated personal networks let him enter into and move frictionlessly among such institutions, serving them even as they benefited him and the poets whose interests he represented. Pearson helped knit these institutions together, reinforcing what he and others of his class assumed was their benevolent hegemony, although his work has largely remained invisible, even "undercover."

Greg Barnhisel is Professor of English at Duquesne University. He is the author of James Laughlin, New Directions, and the Remaking of Ezra Pound (Massachusetts, 2005), Cold War Modernists: Art, Literature, and American Cultural Diplomacy (Columbia, 2015), and Code Name Puritan: Norman Holmes Pearson at the Nexus of Poetry, Espionage, and American Power (forthcoming from Chicago, 2024).

Banner image by Charles Sheeler licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

References

Note on archival sources: Archival materials used in this essay draw from the following collections; the endnotes will use the abbreviations following the names of the sources below. My gratitude to Patrick Gregory for granting permission to quote from the correspondence of Horace Gregory; to New Directions Publishing Corporation for permission to quote from the correspondence of Ezra Pound, H.D., and James Laughlin; to the Beinecke Library, Yale University, for permission to quote from the correspondence of Norman Holmes Pearson.

• Bryher Papers, (GEN MSS 43), General Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. (Bryher)

• Horace Gregory Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries. (HG)

• Grove Press Records, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries. (Grove)

• HD Papers (YCAL MSS 24), American Literature Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. (HD)

• John Hamilton Edwards Collection of Ezra Pound, Department of Special Collections and Archives, McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa. (Edwards)

• Ezra Pound Papers (YCAL MSS 43), American Literature Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. (EP)

• New Directions Publishing Corporation records (MS Am 2077), Houghton Library, Harvard University. (ND)

• Norman Holmes Pearson Papers, (YCAL MSS 899), American Literature Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University. (NHP) All references here from the "Correspondence" series unless indicated otherwise.

• Tom Wolfe Papers, Manuscripts and Archives Division, New York Public Library. (Wolfe)

- James F. English, The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the Circulation of Literary Value (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005). [⤒]

- Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., The Vital Center: The Politics of Freedom (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1949). [⤒]

- See Marilyn Satin Kushner and Kimberley Orcutt, eds., The Armory Show at 100: Modernism and Revolution (New York: Giles Books, 2013). [⤒]

- See my Cold War Modernists: Art, Literature, and American Cultural Diplomacy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015). [⤒]

- See Annette Debo, The American H.D. (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2012), esp. 84-109; Annette Debo, "Norman Holmes Pearson: Canon-Maker," Modernism/modernity 23.2 (April 2016), 443-62; Hollenberg, Between History and Poetry: The Letters of H.D. and Norman Holmes Pearson (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1997). The only other extended discussions of Pearson's life are Robin Winks, Cloak and Gown: Scholars in the Secret War (New York: Quill, 1987) and Timothy Naftali's unpublished 1983 Yale senior paper "Yale Ph.D., OSS, CIA: Sherman Kent, Norman Holmes Pearson, and the Development of an American Intelligence Profession." [⤒]

- Winks 252. [⤒]

- NHP, "The American Poet in Relation to Science," American Quarterly 1.2 (Summer 1949), pg. 124 [⤒]

- NHP, "The Escape from Time: Poetry, Language, and Symbol: Stein, Pound, Eliot," in Voice of America Forum Lectures: Modern American Literature (Washington, DC: Voice of America, 1961), pg. 60. [⤒]

- NHP, "American Poet" 126 [⤒]

- NHP, "American Poet" 126 [⤒]

- NHP, "Ezra Pound" headnote, in Pearson and Benét, eds., Oxford Anthology of American Literature (New York: Oxford University Press, 1938), pg. 1660. [⤒]

- NHP to Benét 11 Feb. 1936; Stanley Williams to Howard Lowry of OUP 12 Feb 1937 (NHP "Oxford Anthology material") [⤒]

- Quoted in Debo "Norman"; Alan Golding, From Outlaw to Classic: Canons in American Poetry (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995), 3, 110-1. [⤒]

- Norman Holmes Pearson and L.S. Dembo, "Norman Holmes Pearson on H.D.: An Interview," Contemporary Literature X.4, 435. [⤒]

- NHP to EP, 9 Aug. 1937 (EP) [⤒]

- Dorothy Pound to NHP, 21 March 1949 (NHP) [⤒]

- Craig La Drière to NHP, 6 July 1951 (NHP). For the full story of the Square Dollar Series, see my "'Hitch Your Wagon to a Star': The Square Dollar Series and Ezra Pound," Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 92.3 (Sept. 1998): 273-96. Marshall McLuhan's connection with Pound seems to be that he had taught Hugh Kenner, author of the first book-length study of the poet's work. [⤒]

- John Kasper to NHP, 2 Aug. 52 (NHP) [⤒]

- NHP to EP, 4 Feb 1955 (EP) [⤒]

- Alec Marsh, Ezra Pound and John Kasper: Saving the Republic (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015). [⤒]

- EP to NHP, 30 Aug. 1956 (NHP) [⤒]

- EP to NHP, n.d. 1957 (NHP) [⤒]

- NHP to EP, Sept. 1956 (EP) [⤒]

- NHP to EP, 10 March 1957 (EP) [⤒]

- EP to NHP 24 May 1957. While Pound's biographer David Moody has said that Pound "was never a white supremacist" (David Moody, Ezra Pound: Poet: The Tragic Years, 1939-1972 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 384), I profoundly disagree with this; and Marsh, who knows this period of Pound's life as well as anyone including Moody, agrees, telling me in an email that "there is no question in my mind but that Pound was a white supremacist — his vision of earth and cosmos, what I call his metapolitics — demanded it." [⤒]

- NHP to John Edwards, 5 Nov. 1953 (Edwards) [⤒]

- NHP to John Edwards, 31 Jan. 1954 (Edwards) [⤒]

- Thomas K. Wolfe Jr., "An Annotation of Canto XLVII," 1952 (Wolfe). Wolfe was a student in Yale's American Studies Ph.D. program in the mid-1950s, and Pearson directed his dissertation after the department initially rejected it. Wolfe delivered the eulogy at Pearson's 1975 funeral. [⤒]

- NHP to JL, 4 Aug. 1953 (ND) [⤒]

- NHP to Robert MacGregor, 14 Feb. 1956 (ND); NHP to John Edwards, 11 July 1955 (Edwards) [⤒]

- NHP to John Edwards, 12 April 1951 (Edwards) [⤒]

- NHP to EP 22 Feb. 1953 (EP) [⤒]

- NHP to EP 31 Jan. 1954 (EP) [⤒]

- NHP to EP, n.d. Sept. 1956 (EP) [⤒]

- NHP to EP, 3 Aug. 1953 (EP) [⤒]

- Ron Rosenbaum, "Peter Matthiessen's Lifelong Quest for Peace," Smithsonian Magazine May 2014. [⤒]

- Debo, American 35 [⤒]

- Schaffner, Perdita. "Keeper of the Flame," in Michael King, ed., H.D. Woman and Poet (Orono, ME: National Poetry Foundation, 1986), 33 [⤒]

- NHP to HD, 31 August 1944 (HD) [⤒]

- NHP to HD, 28 Aug. 1946 (HD) [⤒]

- NHP to HD, 8 Dec. 1946 (HD) [⤒]

- HD to NHP, 10 Dec. 1945 (NHP "HD publication materials") [⤒]

- HD to NHP, 8 Aug. 1948 (NHP "HD publication materials") [⤒]

- "Norman Holmes Pearson on H.D.: An Interview," 436. [⤒]

- NHP to Horace Gregory, 4 Feb. 1949 (HG) [⤒]

- NHP to HD, 27 Nov. 1946 (HD) [⤒]

- Kurt Wolff to NHP, 2 Dec. 1946 (NHP "HD publication materials") [⤒]

- NHP to Horace Gregory, 22 March 1948 (HG) [⤒]

- NHP to HD, 8 Aug. 1948, 24 Oct 1948 (HD) [⤒]

- NHP to Horace Gregory, 20 Aug. 1956 (HG); NHP to Barney Rosset, 14 Feb. 1958; NHP to HD 26 Jan. 1957 (NHP "HD publication materials"); Michael Boughn, H.D.: A Bibliography 1905-1990 (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 1993), 48-51. [⤒]

- Royalty statements, 31 Dec. 1957 and 30 June 1958 (Grove) [⤒]

- "The Moon In Your Hands" (New Yorker 20 July 1957: 29), "The Revelation" (Nation 31 Aug. 1957: 94), sections 4, 5, and 37 of "Vale Ave" (Poetry Dec. 1957: 149-51), "Do You Remember?" (Atlantic Monthly April 1958: 42), "Sagesse" (Evergreen Review Summer 1958: 27-36). The New Yorker contribution is not listed in Michael Boughn's H.D.: A Bibliography 1905-1990. [⤒]

- NHP to Barney Rosset, 14 Feb 1958 (NHP "HD publication materials") [⤒]

- Barney Rosset to NHP, 30 July 1963 (NHP "HD publication materials") [⤒]

- NHP to Judith Schmidt of Grove Press, 5 Aug. 1963 (Grove) [⤒]

- NHP to Barney Rosset, 23 Feb. 1960 (NHP "HD publication materials") [⤒]

- NHP to HD 4 Oct. 1960 (NHP "HD publication materials") [⤒]

- NHP to Bryher, 16 Oct. 1961 (Bryher) [⤒]

- NHP to JL, 11 Oct. 1971 (NHP "HD publication materials") [⤒]

- NHP to Robert Duncan, 7 Aug. 1960 (NHP) [⤒]

- "Norman Holmes Pearson on H.D.: An Interview," 442. [⤒]

- NHP to Bryher, 2 Jan. 1965 (Bryher). The "pornography" Pearson refers to were several controversial titles that Rosset published, including D.H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover, William S. Burroughs' Naked Lunch, and Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer. [⤒]

- Donald Allen, ed., The New American Poetry 1945-1960 (New York: Grove Press, 1960). For more on Grove, see Loren Glass, Counterculture Colophon: Grove Press, the Evergreen Review, and the Incorporation of the Avant-Garde (Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2013). [⤒]

- JL to NHP, 19 Nov. 1971 (NHP "HD publication materials") [⤒]

- Susan Stanford Friedman, personal email to the author, 10 Nov. 2021. [⤒]

- Robert Duncan to NHP, 12 Sept. 1960 (NHP) The University of California Press finally brought it out in 2011 to a limited but rapturous reception, such as Jed Perl, in the New Republic, calling it "the book that could save American art" (Jed Perl, "Magnum Opus," New Republic 4 Jan. 2011 https://newrepublic.com/article/80844/the-picture-book-that-could-save-american-art). [⤒]

- On Laughlin and Harry Brown, see James Laughlin to NHP 26 April 1971, 22 and 30 June 1972 (ND). [⤒]

- On Laughlin's publishing campaign for Pound, see my James Laughlin, New Directions, and the Remaking of Ezra Pound (Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005). [⤒]

- Hollenberg 198. [⤒]

- Pound quoted in Barbara Guest, Herself Defined: The Poet H.D. and Her World (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1984), 313; HD quote from NHP to James Laughlin, 11 March 1961 (NHP "HD publication materials"). The Nation article in question was David Rattray's "A Weekend with Ezra Pound," 16 Nov. 1957. [⤒]

- NHP to Bryher, 2 Jan 1965 (Bryher) [⤒]

- JL to NHP, 26 April 1971 (NHP) [⤒]

- NHP to Bryher, 23 April 1967 (Bryher) [⤒]

- NHP to JL, 1 April 1947 (ND) [⤒]