Tan Lin

In Tan Lin's work, there has long been an affective interchangeability between people, objects, texts, and images. I suggest that there is a continuous throughline between Lin's experimentations with affect, form, and medium, and Lin's meditations on immigration and race, through what I term "quantum raciality." From the standpoint of objecthood and animacy, there is a breadth of scholars in Asian American studies — Mel Chen, Joseph Jeon, Anne Anlin Cheng, Vivian Huang, Michelle Nancy Huang, and Leslie Bow, to name a few — who have adroitly described a relation between Asian racialization and objecthood. I follow their work to consider not only the objecthood that Asianness affords, but the very liminal state of becoming. Quantum raciality expands upon Deleuze and Guattari's "becoming" in A Thousand Plateaus, a transformation they describe as "perfectly real": "We fall into a false alternative if we say that you either imitate or you are. What is real is the becoming itself, the block of becoming, not the supposedly fixed terms through which that which becomes passes. Becoming can and should be qualified as becoming-animal even in the absence of a term that would be the animal become."1 Lin locates race not in the destination of such transformations, but in phenomenological ambiguity, in the becoming itself. Quantum raciality does not perceive race, or the condition of the diasporic subject, as a fixed category, but one that only exists precisely through the incapacity to locate it. After all, as Homi Bhabha writes, "An important feature of colonial discourse is its dependence on the concept of 'fixity' in the ideological construction of otherness. Fixity, as the sign of cultural/historical/racial difference in the discourse of colonialism is a paradoxical mode of representation: it connotes rigidity and an unchanging order as well as disorder, degeneracy and daemonic repetition."2

In his memoiric essay "A Few Versions of Earliness," Lin writes,

The objects in these photographs, like the period of my adolescence and [my father's] adulthood, are merely parts or relations of some other thing. In this sense the objects never imitate anything but life itself, and they do so with relentless imprecision, reproducing people as books and objects as humans all the time, confusing beards with hemlock trees, aunts with TV sets, and children with (in the 1970s and '80s) Dairy Queens, Hall & Oates, portable radios, coal mines in Nelsonville, pieces of pottery, Broadway musicals, gene synthesizers, audience analyzers, and Gilligan's Island.3

In this scene, he and his sister Maya Lin sort and photograph the objects left behind in their late father's home in Santa Barbara: a collection of former gifts from their childhood including toys, art supplies, books, and so forth. Lin describes his father as someone who despised and eschewed the materialistic holidays of normative American culture, boycotting rituals of gift-giving throughout his childhood and leaving the emotional labor of gifting to their mother; yet he and Maya find that their father had taken their childhood gifts with him when he had moved out of the family home. The curious menagerie of memorabilia become patinas of memories, with the affective presence of their father and the presence of their family at large cathected onto these objects. And yet there is something more here than the coagulation of feelings: the objects "reproduce people" as the things, mutual becomings that bleed humans into things and things into humans. As Lin concludes this essay's chapter, "A family does not conclude in an object; a family is a disappearing medium with a few objects that someone left inside it. My father's obituary, like the future, or like a version of earliness, passes through some of these things, none of which is death, and this death, which is not exactly his, leaves traces in the objects left by it. So there is no real distinction between my father's existence and his nonexistence." The family is a form characterized by its unsolidity, a quantum presence not unlike an electron in its atomic orbital, both there and not there at once and captured in "traces." The memorial fragments, in Lin's telling, become frozen in their moments of observation, with the "existence and . . . nonexistence" of Lin's father being a continuous, rather than discrete, distinction.

I have written elsewhere on one of the becomings Lin mentions — the "aunts with TV sets" — which takes the form of his remarkable "ambient novel" Insomnia and the Aunt. It is in the affective flatness of the television that he finds the quality of racialized existence as a Chinese person, as his aunt effectively becomes the television in the haze of his memory.4 The objects in Lin's cataloging litany seem to bear a more general function when they "imitate nothing but life itself" with "relentless imprecision." They do so, however, in the broader context of a memorialized life riven with grief over homeland and a life of disappointments. The objects provide "order" to a series of events that lack a distinctive outcome. "My father never intended to be a potter and he never intended to move from Fuzhou to Ohio in 1957," explains Lin. "His life, like the various items in a photograph, was an ending without much of an ending or a teleology without much that is teleological." The aunt becomes a television, the father becomes a potter, the toys become a story.

In a sense, Lin has been interested in these becomings for quite some time. His long-evolving text, Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004. The Joy of Cooking, includes several short fragments of manifesto-like meditations on aesthetic theory. In "4C -NESS", for example, Lin writes: "A beautiful poem is a painting that can be repeated over and over again," and "Novels were the earliest form of photography known to the human retina," arguing for a visual phenomenology to experience the literary (poetry as paintings, novels as photography). Lin is invested in becomings across questions of media, race, and culture alike, refusing to allow any arborescent essentialism to take epistemological root. As part of this wideness of focus, Lin's becomings are always already happening and cross-pollinating. If Tan Lin observes any constancy, it is in inconstancy. Consequently, quantum mechanics offers an appropriate heuristic that expands upon Deleuzian becoming (itself one node of the rhizome concept, derived from Deleuze and Guattari's appropriation of botany), enabling Lin's anti-identitarian explorations of racial otherness, as well as a disruption of the problem of "fixity," as noted by Bhabha above. In quantum mechanics, as opposed to classical physics, electrons can never be precisely located, but rather mapped into probabilistic zones called orbitals.5 Consequently, quantum mechanics establishes uncertainty and unknowability as fundamental attributes of matter, conceptualizing matter as inherently fluctuating, never bearing discrete, molar permanence of either state or location. In a sense, quantum raciality can account partly for the means by which Lin works with and against the discursive formation of identity. Lin has repeatedly experimented, both through form and content, with phenomenological mashups, utilizing one form or medium to access another, and vice versa, often aiming for aesthetic experiences that draw upon each medium not as inherent or fixed, but as bearing both particle and wave characteristics, recognizable in form yet refractive.

In this regard, I follow the work of such scholars as Michelle Huang and Derek Lee, who have theorized quantum entanglement in Asian North American literature. Huang and Lee each discuss quantum entanglement in Ruth Ozeki's landmark speculative novel Tale for the Time Being, which Ozeki deploys narratively throughout Tale's storyline. Huang coins "ecologies of entanglement," which refers to "networks of circulation that diffuse the boundaries of the human by foregrounding the relationships between us and the world with which we interact, including the environment. This framework focuses on the emergence of subjects and objects as effects of epistemological cuts, which shifts the 'object of study' from objects in themselves onto the phenomena that create and bind them." Thus, writes Huang, "thinking about entanglement ecologically allows for the synthesis of more than two agents, but not in an undifferentiated, free-floating manner."6 Meanwhile, Derek Lee's formulation of the "postquantum" offers a theorization of the means by which authors of color deploy the tropes of quantum mechanics both with and against the prevailing scientific consensus within contemporary western literary epistemologies.7 But whereas Ozeki is rather explicit in her engagement of quantum narrative, quantum raciality permeates the methodological fabric of Lin's deployment of race, which often comes secondarily or off-handedly.

We can see this in Heath (plargiarism/outsource) and the Heath Course Pak, which contain some of Lin's early reflections of Asian Americanness. Not unlike "A Few Versions of Earliness," the Heath texts contend with something like mourning — specifically, a fixation of the media unfolding of Heath Ledger's 2008 death by drug overdose. The Heath texts are multimedial, containing a pastiche of what can be described as internet readymade objects, screenshots of late-2000s Google searches, RSS feeds, ads, and other ephemera spliced in with Lin's ambient poetry throughout. Heath Course Pak contains his 2009 interview with Chris Alexander, Kristen Gallagher, and Gordon Tapper, where he explains the intentions of the work in detail: "I would generally say that the 'work' of Heath is a 'mode of subjectivity' or 'subjective space' and it is . . . a process of blind labor (someone is clearly laboring in Heath) whose product is attention, where attention produces the objects that interest us. I think it is unclear what Heath, the work, is. Heath the actor and the book ('work') is a series of theatrical events, discrete articles, texts, ads, achronological effects, etc."8 In effect, explains Lin, Heath plays with the construction of the subject, but largely through the performative assemblage of collective online discourse to examine how Ledger's death produced a theater of signification. Thus, like the quantum particle, the dead subject in Heath keeps changing — multiple Heaths, published in diffuse, rhizomatic ways simultaneously rather than a singular text that changes in a linear fashion.

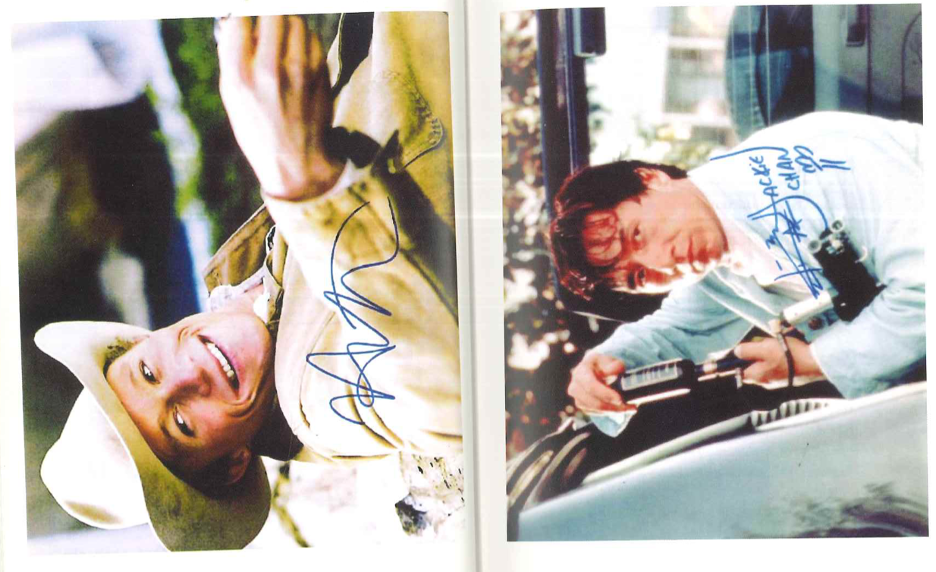

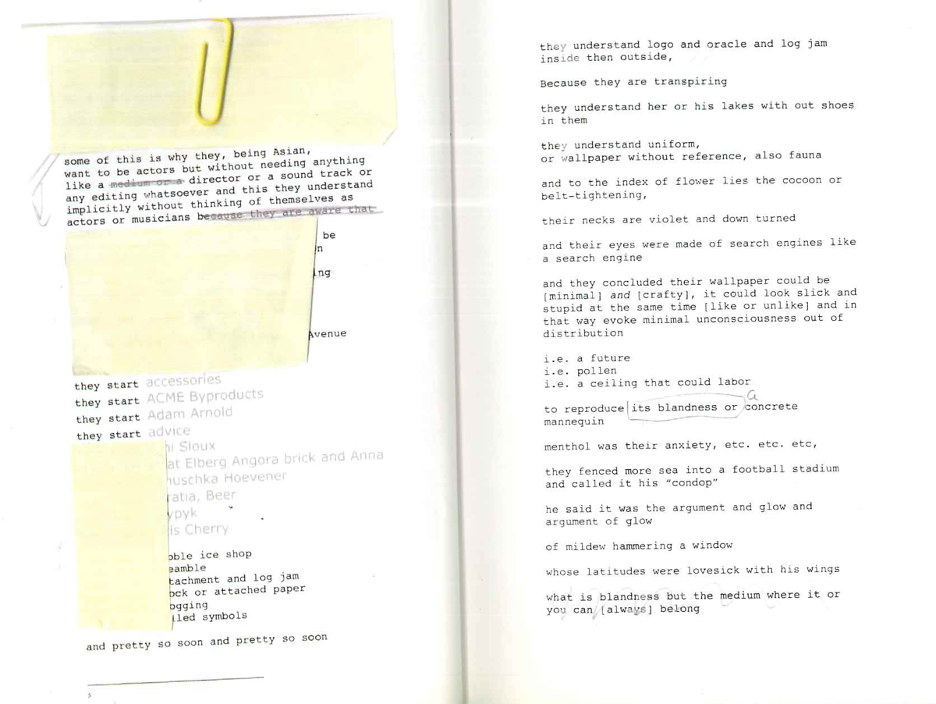

Among the menagerie, Lin includes a number of fascinating artifacts that invoke various forms of Asianness or Chineseness. The first is a juxtaposition of autographed movie stills: a grinning Heath Ledger in his role as Ennis Del Mar in Brokeback Mountain, and Jackie Chan from the height of his career. This is immediately followed by a poem, obscured by post-its and pencil scratchings, beginning with "some of this is why they, being Asian, / want to be actors but without needing anything / like a medium or a director or a sound track or / any editing whatsoever and this they understand / implicitly without thinking of themselves as / actors or musicians because they are aware that."

The poem goes on to list several traits about "they" — presumably "Asians" — such as starting "accessories" and "ACME Byproducts," on the next page adding "and their eyes were made of search engines like / a search engine."9

Concerning the initial juxtaposition between Ledger and Chan, Lin muses in the aforementioned interview that confusing Chan and Heath is not due to visual miscrecognition, but that he does not seem to perceive Heath visually, as a matter of fact. Rather, says Lin, Heath "exists as a kind of format-dependent scanning, as does the work itself." To say that Heath exists as "a kind of format-dependent scanning" suggests that the figure of Heath Ledger begins to dissolve into the soup of online searches and informatics, accessible not through a deep read of subjective interiority but a wide scan of surface. There is thus a curious connection between this juxtaposition/confusion and his poem's mention of "their eyes were made of search engines like / a search engine" — the Asian's eyes as that which retrieves information, both in search of, and constituted by, code. Jackie Chan as Heath is a glitch, but perhaps an inevitable one. Chan, like Heath, is a figure before a person, an assemblage of ads and collective public signification rather than a full subject, but also one who is Asian, whose racial form, from Lin's perspective, bears an ontological dimension of search engine-ness. The metonymic "eyes" of Chan and Heath, considered together, produces a phenomenological techno-orientalism: a racialized perception insofar as the eyes scan for information and data like a robot indifferent to sublime aesthetics characteristic of the subjectivity of modern western humanism.10 Lin has no investment in disrupting stereotype, in other words; rather, he explores the affective dimensions of the conditions it sets. Here, quantum raciality is mapped onto the simultaneous ideas or acts of being and seeing Asian through the hallucinatory haze of the informatics of Heath Ledger. The search engine eyes suggest an onslaught of informatics, which slips, in Lin's poem, into the Asian as that which consumes and becomes code. But there is also something to be said about the repetition — "search engines like / a search engine"; the eyes become search engines which in turn become like a search engine. The object of comparison can only approximate being itself, a quantum uncertainty principle reigning in every step of the construction.

Lin goes on about his thinking about subjectivity, Asian American self-formation, his skepticism of identity, and the ubiquitous hegemony of text:

I think the subject and in particular an Asian American subject, is diversely compounded and specific, even stratified, in terms of markers/functionality-the various index cards, but also the preciseness and calculations of stereotypes, Jackie Chan vs. Heath Ledger, each with their associational referents, each of which, in turn, is subject to economic calculations, tabulations, and distribution patterns. In this scenario, I wonder how useful it is to think of a self. Is Jackie Chan a self? [ . . . ] But for me, he's a kind of pop up hallucination of Heath i.e. a hallucination of a hallucination (vs. a kind of Asian American clown (who I like)) [ . . . ] So I think that the idea of a self is something I wanted to throw into relief, not because it's fluid or because its rigidly stratified (I think it's probably both) but because "self" or identity don't seem a very productive category of thinking-it's a kind of ideological coating on a commodity, i.e. part of a particularly anthropomorphic mode of subjectivity grounded in a critique of capitalistic modes of production.11

Here, Lin expresses a desire similar to Kandice Chuh's, aiming for a subjectless discourse that dissolves subjective wholeness upon its invocation.12 However, unlike Chuh's Derridean approach, Lin's critique of selfhood is decidedly Marxist in its orientation, locating subjectivity (particularly for the Asian American subject) as calculations of stereotypes and "associational referents, each of which, in turn, is subject to economic calculations, tabulations, and distribution patterns." This critique is suspicious of how selfhood and identity are continuously constituted and targeted by their market referents. Selfhood may, in fact, be a trap for Asian American subjectivity, "an ideological coating on a commodity." (This "coating" perhaps complicates or deepens his ruminations of the patina of memory on his father's objects as he and his sister go through them.) He goes on:

The present feels like a language-saturated moment, and I think this is different from fifteen years ago which was more of a visual/image based and anti-language culture.... everyone is texting/writing, and most of the things we look at and see on the web is language, i.e. the material bases of what we see lie in program codes, core codes, or scripting languages.... So here, I was not particularly thinking of the self as overrun by advertising (Made in Taiwan) or even a fluid or socially constructed entity. I was interested in how I could NOT think about the self except as a kind of evolutionary writing/text production (i.e. a subjectless process) linked to specific technological affordances and constraints.13

The self emerges, then, not as an a priori, ideologically suffused entity, but as an observable phenomenon of code and text.

Lin remains preoccupied with Asianness, even while retaining his rightful skepticism of identity and the politics that cohere under its banner. For Lin, Asianness seems to exist less in the essentialist matter of ethnic ancestry or in strategic political mobilization, but rather in a phenomenology of perception. It is here that we find quantum raciality: Asianness is not so much something that Jackie Chan possesses but, like the family in "Earliness," exists as a kind of quantum orbital of approximate localities — in the confusion itself. Here, Antonio Viego's Lacanian description of the problematic of epistemological capture is appropriate: "ethnic-racialized subjectivity has suffered from too much understanding. This is not to say that ethnic-racialized subjectivity and experience has been understood, but rather to say that the project of understanding it is imagined as completely within reach."14 To capture Asianness (or race more generally), to try to measure it or provide it with static attributes, is a folly; akin to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle's dictum that a particle's location and its speed cannot be observed simultaneously — that measuring one produces uncertainty with regards to the other — race can only be understood in a complex set of relations that refuse fixity or stillness. In this analogy, then, race is the atomic orbital, not the particle for whose position within the orbital one searches.

Taking the Heath texts and "Earliness" together, it is worth considering that the moment of quantum ambiguity emerges, in each case, in the wake of a death. Loss, intriguingly, is a key component of one's subject formation even as it is precipitated by the destruction of another. Judith Butler writes: "For loss to predate the subject . . . we must consider the part that loss plays in subject formation. Is there a loss that cannot be thought, cannot be owned or grieved, which forms the condition of possibility for the subject?"15 For Butler, loss is a prerequisite to subjectivity itself; the loss of the possibility of love, and the denial of grief, is a condition for queer subjectivity. Yet, for Lin, there is not so much melancholia — that is, an ongoing feeding upon the lost object as in Butler's example — so much as there is an uncanny transmogrification of what — of who — has been lost. Inverting melancholia, Lin's grief is characterized by dissolution rather than solidity. Returning to "A Few Versions of Earliness," Lin writes: "People like my father become less individual with the passage of time. And that is probably why, when trying to track dead people on the web, especially recent immigrants, or looking at gifts from childhood, one remembers waiting for a few things loved by someone else, as if people could be caught in a series of procedures that replace memory with algorithms or dates connected by hyphens in a search string."16 Not unlike Heath, Lin's father dissolves in memory, becoming the collection of gifts left behind, memories themselves becoming codes & algorithms. Whereas Heath Ledger becomes Jackie Chan, Lin's father the "recent immigrant" becomes abstracted further, "less individual with the passage of time" and diffused across the multitude. Here, loss does not so much form the subject as undo the memory of object, reducing the lost person to an assemblage of affective traces from a life that had been suffused with an ambivalent, diasporic yearning for homeland. These gifts were not representative of the desires of Lin's father — he had despised them, after all, as embodiments of American material excess — yet they become associated with him ironically through his enigmatic hoarding of disavowed objects, a contradiction that corresponds to the paradoxical narrative of his life. These are the paradoxes that refuse fixity, even as they thread together to form a narrative.

To close this meditation on Tan Lin's quantum raciality, I would like to gesture to his recent work "The Fern Rose Bibliography"(2022), in which he elaborates further on the death of both of his parents. He observes,"My parents treated books a little like garden tools or kitchen implements, which is to say it is impossible to separate my parents' reading habits from the things that would transform them into Chinese persons in America and then into Americans, and then, in a kind of reverse chronology, back into Chinese persons upon their deaths."17 In providing a catalog of his parents' books as an annotated bibliography consisting of his personal memories of their texts, Lin describes how his parents assumed reading as an American assimilative strategy. The desubjectification of death, however, returns Lin's parents to Chineseness in his rendering. Lin describes his father's death as "mildly Asian, at least in Ohio," and asks, "What is the history of a family that reads a lot, a history which I confuse with furniture and a smell [. . .] ?"18 In the wake of his parents' deaths, Lin relies on a multiply-oriented sensorium, linking books, furniture, and smell by recalling the Chinese name of a particular flower's scent ("cháhu (茶花)"), a flower that his father once grew as a stand-in for the family's history. Lin recalls smelling the cháhu each summer, and his father explaining the name of the plant, which also bears 900 names in Japan, in anticipation of his, Lin's mother's, and his own death, but the fullness of its meaning may evade language altogether.19 Such is yet another example of how Tan Lin provides us with a means of thinking through race phenomenologically, identifying its affective experience not in certainties but in ephemera, in zones as approximate as olfactory fragments. Quantum raciality is not an interpellation but an evasion of capture, a way of feeling race as diffuse as the memories of those who bequeathed it.

Takeo Rivera (Twitter, @TakeoRiveraPhD; Bluesky, @takeotiveraphd.bsky.social is assistant professor of English at Boston University. He is author of Model Minority Masochism: Performing the Cultural Politics of Asian American Masculinity and is also an award-winning playwright.

References

- Gilles Deleuze and Féliz Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. with a foreword by Brian Massumi (University of Minnesota Press, 1987), [PAGE #]. Emphasis added.[⤒]

- Homi Bhabha, The Location of Culture (Routledge, 1994), 94.[⤒]

- Tan Lin, "A Few Versions of Earliness," Canopy Canopy Canopy Issue 23 (20 November 2018), n.p., https://canopycanopycanopy.com/contents/a-few-versions-of-earliness.[⤒]

- Takeo Rivera, Model Minority Masochism: Performing the Cultural Politics of Asian American Masculinity (Oxford University Press, 2022).[⤒]

- "These spherical and dumb-bell shapes are telling us where we are going to find an electron wave. Rather than going around the nucleus like little pellets, we have to think of electrons as vibrating surfaces taking on bulbous shapes with the nucleus at the centre. . . . These regions around a nucleus where electrons vibrate are no longer thought of as orbits, so we call them 'orbitals instead." Tim James, Fundamental: How Quantum and Particle Physics Explain Absolutely Everything (Penguin Books, 2020), 46.[⤒]

- Michelle Huang, "Ecologies of Entanglement in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch," Journal of Asian American Studies 20, no. 1 (February 2017), 98.[⤒]

- Derek Lee, "Postquantum," MELUS 45, no. 1 (Spring 2020): 1-26.[⤒]

- Tan Lin, HEATH COURSE PAK RFC (Counterpath Press, 2012), n.p.[⤒]

- Lin, HEATH COURSE PAK RFC.[⤒]

- This is a continuation of the point I make at greater length in Model Minority Masochism with regards to Lin's work, in which I argue that techno-orientalism exceeds the representational, affecting perception and proprioceptive awareness itself. The result is a kind of techno-orientialization of the self that is neither "positive" nor "negative," but is rather a way of embodying a self in space via an affective flatness one might superficially label "stereotypical."[⤒]

- Lin, HEATH COURSE PAK RFC.[⤒]

- Kandice Chuh, Imagine Otherwise: On Asian Americanist Critique (Duke University Press, 2003).[⤒]

- Lin, HEATH COURSE PAK RFC.[⤒]

- Antonio Viego, Dead Subjects (Duke University Press, 2007), 91.[⤒]

- Judith Butler, The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection (Stanford University Press, 1997), 24.[⤒]

- Lin, "A Few Versions of Earliness," n.p.[⤒]

- Tan Lin, The Fern Rose Bibliography, in Cookie Jar 1: Home is a Foreign Place, eds. Pradeep Dalal and Shiv Kotecha (The Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant, 2022), 19. https://www.artswriters.org/downloads/AWG-COOKIE-JAR-1_LIN-TAN.pdf. Cookie Jar 1 is the first in a series of pamphlet compilations. https://cookiejar.artswriters.org/.[⤒]

- Lin, Fern Rose, 57.[⤒]

- Lin, Fern Rose, 43.[⤒]