Samuel R. Delany's Improbable Communities

"I'm promiscuously autobiographical."

- Samuel R. Delany1

"Improvisation, in whatever possible excess of representation that inheres in whatever probable deviance of form, always also operates as a kind of foreshadowing, if not prophetic, description."2

- Fred Moten

In a social media post with the all-capitalized heading "DOUBLE VISION" from June 2022, Samuel R. Delany writes

As a dyslexic, slightly wall-eyed, somewhat myopic black gay writer, I have been seeing double most of my life. Below, are three of the most usual images I see every morning, in the course of making oatmeal for the Big Guy [his long-term lover, Dennis Rickett] and me. [ . . . ] I let one eye drift so that I am actually seeing only with one eye and now really reading with both eyes. [ . . . ] The only thing that actually changed that was my two cataract operations in my early 50s, two years apart, which meant that for a third of the time, I could bring those two images together. I've often wondered why I never wrote about this in fiction, but it's probably because nobody else (that I know of) has. I've broached a couple of times in non-fiction, and here I thought I would write about it directly, since it is probably the biggest factor that influences my "vision" of the world.3

Accompanying this post are four photographs: a tightly cropped close-up of a Black man's eye; a refrigerator overstuffed with take-out containers; a kitchen sink drain basket with barely noticeable glints; and a not-yet-eaten plate of oatmeal with a slanted spoon next to it. The photograph of the Black man's eye appears to be a stock photography image, while the rest, based on Delany's post, are his own snapshots from home. Here, of course, Delany makes both figurative and literal references to how he perceives his surroundings, with a conceptual framing of "vision" both as an indicator of harnessing ocular variation from dominant acuity and as a lens through which he views his approaches to writing. The photographs that go with this post do not visually mimic what Delany describes as "dyslexic, slightly wall-eyed, somewhat myopic." They are unremarkable, quotidian images that contrast with the abundance of personal narrative detail included in the post: naming other writers with some of the same conditions alongside obliquely cast anecdotes about glasses, eye exams, and childhood circumventions of what would now be understood as ableist pedagogical models unattuned to learning differences. The "wall-eyed" modifier with which Delany identifies himself refers to strabismus — commonly if untowardly also known as being "cross-eyed" — which is a misalignment of the eyes, or one eye turned in a different direction from the other eye, causing many with the condition to "see double."4

Moreover, the mastery of observation and breadth of eroto-social experiences for which he is known, particularly in non-fiction work such as Times Square Red, Times Square Blue [TSR, TSB] (1999), where his personal sexual ventures meet the page, prompt a transvaluation of "myopic." Rather than naming optometric nearsightedness or connoting a lack of foresight, "myopic" might instead signify a discernment of bodily contours, of class differences, and an attentiveness to navigating the sexual underground of a pre-1990s "revitalized" Times Square: in the minutiae of Delany's insights from and about this era, transgressively vibrant behaviors overlooked by the dominant public are keenly detectable. As Robert Reid-Pharr writes in his foreword to the twentieth anniversary edition of TSR, TSB, Delany "is not afraid to both look and see."5

Delany infrequently mentions his dyslexia (neurodiverse reading condition) and dysgraphia (neurodiverse writing condition) in print, which he discusses as part of Adult Attention Deficit Disorder (AADD) and does not treat with pharmaceuticals.6 "I had, and have," he states, "no visual ability to remember how words are put together. I can recognize them when I see them. But unless they're in front of me, I can't recall the vowels they contain. I have no command over whether they contain single or double letters."7 Often outlined as moving with and through the instability and/or mis-ordering of words, letters, and syntax, Delany's explanations of how these neurodiverse conditions intervene in crafting his prose retain something of an ambivalence about the labor-intensive process. When asked about the presumptive incongruities between these conditions and the sheer volume and range of writing he has produced over his lifetime, Delany, without celebration, calls his dyslexia "a pain in the ass"8 with nonetheless counterintuitive effects. In one of the extra interviews featured on the bonus disc included with Fred Barney Taylor's The Polymath or, The Life and Opinions of Samuel R. Delany, Gentleman (2009), Delany, in his characteristic candor, asserts: "I have to rewrite things again and again to get correct the things that the lucky lexic in our society cavalierly calls the mechanics. [. . .] maybe the dyslexia is a goad to make things a little better."9,10 Similarly demoting goals of amelioration in favor of the material experiences of attending a Prime Timers sex party—organized gatherings for older queer men—Delany instead contemplates possible difficulties with writing about it. "While I was not particularly nervous sexually about what would happen, there was my worsening ADD," he wonders, "Would I be able to negotiate my medications, food? Sleep? With ADD wreaking havoc on logic and focus, would I be able to document the trip as I hoped?"11 Irreducible to being merely spoken or written, the encounters with this in-progress archive emerge as non-ableist lexicons of the body and the pen.

In welcoming such graphic superfluity, visual-spatial disobediences associated with documentation attentive to neurodiversity thus compel a consideration of what spatio-sexual oscillations, visually textual flows, and bodily rhythms may indicate about how to be queerly "situated in place," that is, to be unstable within the spheres of normative valuation. I use dyslexical, in this essay, to describe the figurative nexus of sexual geographies that invite us to bask in the inconsistent patterns and sense the promiscuous pulsations of TSR, TSB's photo-textual presence.12 La Marr Jurelle Bruce's theory of "madtime" is instructive to consider alongside such rhythmic topographies of eroticized space. For Bruce, "Blackness often sponsors exquisite practices of musical and metaphysical syncopation, [ . . .] eludes official notation, disobeys the dominant beat, activates the offbeat [ . . . ]."13 In TSR, TSB, we might then determine that its syncopated rhythm is also a crip rhythm, a rhythm whose arrangement of Blackness and queerness, however unaccented or accented, refracts the radiance of urban motion via different routes.14

I employ the intentionally inelegant misspelling and merging of the words sex and excess, forming the neologism sexcess.15 The phonetic effect of adding dyslexical to the jammed-together sexcess intentionally, if awkwardly, stimulates a sonic slippage that seeks to highlight Delany's own sexually radical life in considering his literary success. Delany's dyslexical sexcesses, especially in their recalibration of description, offer anti-ableist communicative strategies and how spellings and capitalizations in these contexts often defy grammatical norms. Description itself is part and parcel of a crip communicative praxis whether in reference to alternative textual written descriptions added to an image or to capitalizing each word in a hashtag for more accurate output by screen-readers: #ThroughTheValleyOfTheNestOfSpiders, for instance, disregards the rules related to lowercasing parts of speech such as articles and prepositions in a title. In TSR, TSB, sexual minoritarian subjectivity emerges as queerly "excessive" experiments in form that emulate a lifetime of "excessive" public sex practices. Sexcesses associated with anti-heteronormative modes of relationality, public sex practices, and photo-textual encounters present themselves as Delany's recollections of sexual bodies that queerly and radically break down the distinctions between private versus public eroto-social interactions. And it is these radical breaks in heteronormative and neuronormative propriety, informed by the rhythms of urban and sexual movements reflected in TSR, TSB, which are queer gifts to historical documentation, allowing ways to access the resonant echoes of a sexual underground.

* * *

Delany unapologetically showcases a promiscuity in excess of domesticated notions of sexual experience, what he discusses as desires quenched by "the sexual generosity of the city."16 When being documented in Taylor's The Polymath, Delany estimated that he had well over 50,000 sexual contacts in his life — an underestimation at present to be sure. In addressing these numbers along with early mainstream coverage of AIDS in the 1980s, he calls attention to what was conceived as risky behavior to be 300 sexual contacts a year and, in an incisive tone of amused astonishment at the ignorance about sexual practices of gay men, he does the math for us and says it is more like 300 contacts a month and 2,000 - 3,000 contacts a year.17 At the beginning of The Polymath alongside the ominously evocative ambience of Quentin Chiappetta's musical compositions that undulate through the film, Delany recounts the deeply intertwined connections between public sex and prolific writing, beginning in the 1960s when he was married to poet Marilyn Hacker. He explains that within just a few years he had written and published 5 novels, a feat he considers possible thanks to the availability of sexual opportunities in public restrooms and at other sites such as Tompkins Square and the Williamsburg Bridge. Cut up with bouts of writing and bouts of sex, the structure of his days included running errands, cooking, walking, and reading without de-prioritizing sexual fulfillment; a full 8 or 10 hours of work would be regularly accompanied by sex with 12-15 people in a given day. "The sex made the work bearable," he recalls, "it made the days enjoyable rather than difficult and monotonous. [ . . . ] You felt like you were having a fairly interesting life."18

This sexual-writerly libertinism is of the queerest kind in how it amalgamates the experiential domains of textual and erotic relation as indulgent rewards of craft in modes that radically revise hetero- and homonormative logics as well as hyperbolic notions of white literary heteromasculinity.19 TSR, TSB follows suit. Contextualized in the wake of "sanitizing" New York's Times Square under Rudy Giuliani's Forty-second Street-Times Square redevelopment project, the moral panics surrounding AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s, and the conflation of crime and sex work, TSR, TSB reveals that the justifications for shutting down sites of sexual commerce such as porn theaters, strip clubs, and peep shows was more about the regulation of public sex and the capital gained from "family friendly" tourist dollar than it was about urban safety. Delany outlines the displacement and erasure of thriving interclass sexual communities due to the gentrification and corporate development of Times Square.

Delany collaborated with photographer Phillip-Lorca diCorcia for crucial elements of TSR, TSB's visual presence. Gaining critical acclaim for his photographic series of sex workers in Los Angeles, Hustlers (1990-1992), diCorcia staged these photographs at sites such as Hollywood Boulevard and motels, having the titles of each photograph take on the photographic subject's name, age, birthplace, and fee.20 Along with yet maintaining key aesthetic distinctions from photographs in the Hustlers series, diCorcia's selective panoply of New York City pedestrians in Streetwork (1993-1997), New York (1993-1998), and the later Heads (1999-2001), are art historical reference points for the types of images diCorcia shot to accompany Delany's sexual narratives in TSR, TSB. Portions of what is now the "Times Square Blue" section of TSR, TSB first appeared as Delany's piece "X-X-X Marks the Spot" in a 1996 issue of Out magazine, which featured a photographic essay of four images by diCorcia that did not appear in TSR, TSB.21 In locating diCorcia's photographs together with Delany's own snapshots, TSR, TSB registers its sexual-spatial politics of difference as a photo-textual event that experiments beyond literary form. TSR, TSB allows the spontaneity associated with the sexual geographies in question to marinate in the graphical presence of photographic images and auto-theoretical description. This is observable as a visual-verbal hierarchical disobedience that continually and excessively overlaps in many forms.

A text about sexual spaces and their traces,22 TSR, TSB is structured in two parts, which Delany writes is meant to be "a commitment both to the vernacular and to the expert."23 The "Times Square Blue" section, placed first, is an anecdotal and autoethnographic narrative that reproduces copious examples of dialogues and conversations that Delany participated in and/or overheard. Other than one repetition of one photograph, all of the book's photographs — those both by diCorcia and Delany — appear in this section, which Delany populates with thorough explanations and micro-mappings of cross-class sexual contact within the metropolitan sphere. The subjects of the photographs include shuttered porn theaters, marquees, hustlers, taxi booths, hot dog stands, and streetscapes (peopled and unpeopled). These are augmented by lengthy, overflowing, and, at times, tangential captions that rely upon an excess of formal detail to approximate some of the disjunctions between scopophilic memory and what remains of the physical spaces themselves. Alongside diCorcia's photograph of the Eros I's outside marquee, which boldly declares, "ALL MALE MOVIES" with "MEN OF THE EROS" underneath it — "EROS" orphaned at the bottom — and the four letters of "LIVE" diagonally shoved into the lower-left corner with each letter descending,24 is Delany's caption:

"The west side of the block between Forty-fifth and Forty-sixth Streets held three small theaters. Toward the north end stood the Capri, with a narrow orchestra (six seats on the left of the aisle, three seats to the right) and a narrower balcony. The bus stopped directly before it so that waiting passengers often used its small triangular marquee during the rain. After a small parking lot just to the Capri's south stood the Eros I with orchestra and downstairs dressing rooms. [ . . . ]"25

In addition to mentioning the marquee's triangular shape — a key street photography compositional feature that prompts visual flow26 — in the context of rain, the caption goes on to include information about the pornographic content, live performers, and technological updates among the Venus, the Eros I, and the Capri. Set off in all-bold lettering and taking up about a third of the corresponding page, the sexcessive caption-paragraph may appear to contain "too much information" or to be in need of editing, but these would be regrettably questionable amendments to what is but a fragment of Delany's queer archival record. Put differently, too much is never enough in documenting histories of sexual minoritarian lives. The extraneity is part of what a queer captioning must encompass: that which goes ignored in dominant orderings of knowledge.27 In turn, because they frequently yet inconsistently dominate the photographs, the visual-textual display of the photographs' captions in TSR, TSB trouble their putative subordination to the photographs. This insubordination is also true for "Times Square Red."

The "Times Square Red" section appears second in TSR, TSB, after the "Times Square Blue" section, and is a theoretical exploration of the effects of gentrification that includes Delany's central claim about interclass sexual contact — as opposed to networking — that the erotic urban geographies of New York City facilitated in a pre-Giuliani "redeveloped" Times Square. Described by Delany as having a "mosaic structure,"28 the text's "Times Square Red" section is visible and phantasmatically audible as an asynchronous rhythmic pattern whose sonic structure takes the form of multiply- and, at times, cacophonously-voiced conversations of recurring experiences from the past in the ever-presence of the reading moment. The rhythm here can be heard in the "main" text not being bolded while the bolded text occupies the "marginal" position, giving it, as bolded text, a more visible space within the dominant context of the non-bolded "main" text. Delany's sentence, "while the lure of hustlers most certainly helped attract the sexually available and sexually curious to the area, a good 80 or 85 percent of the gay sexual contacts there [. . .] were not commercial."29 On the following page, the text's bolded marginal commentary/voice pushes us to read it instead of the non-bolded paragraph that follows, the cue here being that the bolded section begins as a conversational aside, continuing with the approximated percentage named on the previous page: "If, as I say, 80 to 85 percent of the (gay) sexual encounters in the Times Square neighborhood were noncommercial . . ."30 Occupying a literally marginal position on the page, the text makes visible the marginality and the sexual practices that it signifies. In questioning the distinctions between commercial and noncommercial sex, the text here emboldens the nuanced repetitions and movements that attend to sexual non-normativity. Repeated from the "Times Square Blue" section with a smaller difference of in-text scale, the sole photograph included in "Times Square Red," taken by diCorcia, is of a hustler named Darrell Deckard. Jolene Hubbs analyzes the ways that the photograph's placement and textual recurrence coextends with embodied forms of movement and stasis pertaining to sex work. "Deckard loiters on the corners of pages," Hubbs writes, "just as he loiters on the corners of midtown streets, his textual availability mirroring his sexual availability."31 When Delany introduces Deckard to us toward the start of TSR, TSB, he makes sure to include, with emphasis, that Deckard is a "good-looking black man of twenty-six,"32 so that we too are in a belated process of all at once cruising, conversing with, and documenting the moment with him alongside diCorcia's photographs. As Hubbs suggests, experiencing these photo-textual features invites us to put aside the conventional impulse to identify or follow in a straightforward fashion.

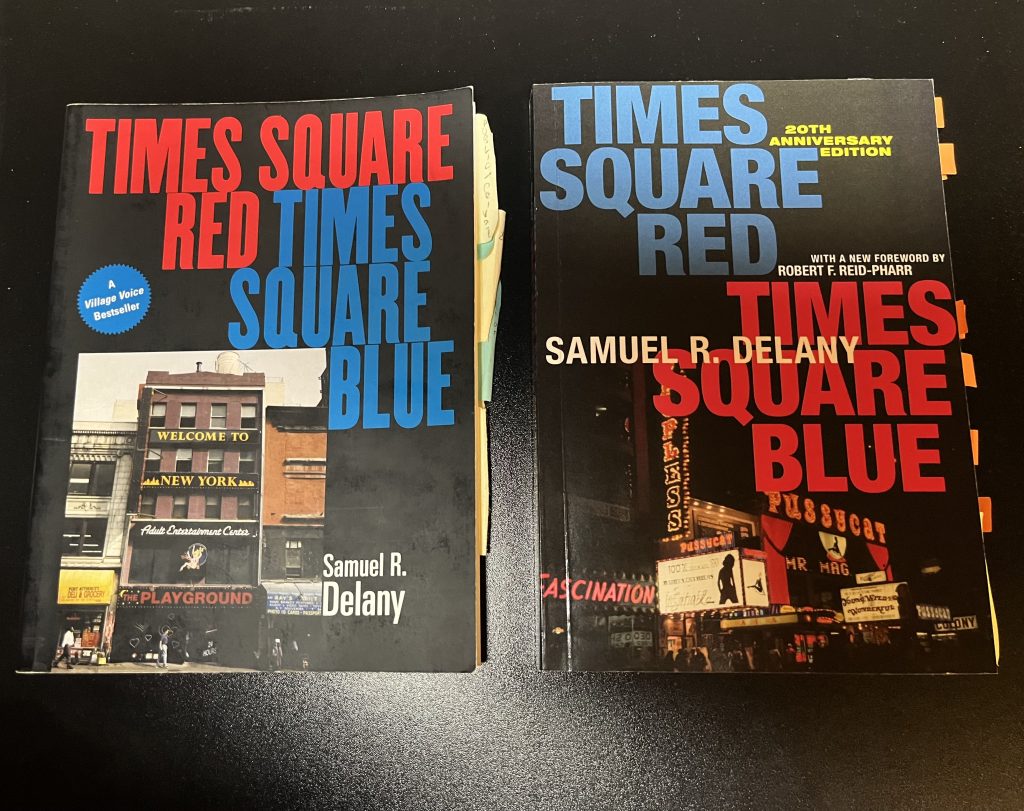

While the selections of the colors blue33 and red to name the sections can mean many things in opposition to each other, their meanings become highly mobile as discrete entities. As far as it pertains to lighting, the title TSR, TSB bespeaks the necessary contradictions that come with documenting sexual histories as such. Calling to mind the flashing blue and red neon lights of the city to initiate the text's framing, the blue can correspond to "[t]he blue light of the St. Mark's Baths"34 that José Esteban Muñoz mentions in his reading of Delany's autobiographical The Motion of Light in Water (2004). As for red's obvious associations with red light districts, the issue of Out magazine mentioned earlier introduces Delany's piece and diCorcia's photographs with "the red lights are off and Disney and souvenir shops are in."35 Key here too is the purposeful mis-ordering of the sections: the "Blue" section comes before the "Red" section even though the book's title promises otherwise. Just like the seductive prurience of participating in public sex, this mis-ordering of the sections vis-à-vis the title functions like public sexual space itself: it defies eroto-relational norms of expectation and is more about the delight in not knowing what you may encounter. The sections' ordering in the book thus encourages the breakdown of public/private space and its concomitant sexual practices. The changes to the cover of TSR, TSB's twentieth anniversary edition appear to play purposefully with these instabilities as well. The first edition's matte cover and elongated lettering also includes diCorcia's iconic photograph of The Playground, a sex shop whose "Welcome to New York" and "Adult Entertainment Center" signage reappears, within the book, in diCorcia's photograph of the taxi dispatcher booth. This easily overlooked but key photo-textual rhythmic feature is lost if only experiencing the text in its newer edition, which replaces diCorcia's cover photograph with a David Herman stock photography image of the Pussycat's extravagantly lit exterior whose neon lighting shouts, "FASCINATION," and captures the vertical "TOPLESS" midway through "stripping down" as it individually penetrates the illuminated outlines of the letters. Unlike the first edition, the high gloss cover of TSR, TSB's commemorative edition, in switching to a chunky lettering of the title, changes "Times Square Red" to the color blue and vice versa.

The garish yet attractive glow of neon brings us to what Katherine Bussard calls the "irrationality of lighting" that characterizes much of diCorcia's photography is alternatively identifiable in his image of Stella's bartender that appears on page 94 of the book.36 Drawing on diCorcia's discussions of his own work, Bussard explains that the "irrationality" corresponds to how diCorcia simultaneously works with chance and staging: the inconsistencies of where the light hits; a severely close depth of field; and strategies including affixing strobes out of sight on scaffolds, for instance, give his photographs cinematic and/or theatrical qualities.37 It is nonetheless clear, throughout TSR, TSB, which photographs are by Delany and which are by diCorcia: all of Delany's snapshots contain automated orange-yellowish date-stamps set in digital font and branded into one corner of his images. In turning back to a moment in The Polymath, Delany, ushering us through a theater to demonstrate "how public sex operates," uses his cane to guide us through the complex sexual geography of the space. This includes narrating moments such as the unscrewing and screwing of lightbulbs, depending on the exhibitionistic proclivities of an audience; the darkness of the back row where the sex tends to occur; the overheard conversations and various bodily sounds of sexual activity; and the ebbs and flows of foot-traffic in the aisles. Delany tells us that with public sex, "Everything is half hidden and half revealed."38

I end with the beginning of the first volume of Delany's published journals. In his editor's introduction to the volume, Kenneth R. James discusses "editorial puzzles with no solutions,"39 that is, the challenges related to chronologically reproducing in print what was visually produced multi-directionally. He writes: "One of Delany's consistent work habits was to fill his notebooks from two directions at once: front to back and back to front. This often made it impossible to determine whether a given passage had been written before or after a neighboring one."40 The editorial mapping described here bears the weight of the erratic routes of an always in-process account of encounters, reproduced as sexually promiscuous forms of writing. Becoming immersed in what is endlessly out of place shows, even if momentarily in historical time, how we might dwell in the margins before they are torn down.

Y Howard is Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of English and Comparative Literature at San Diego State University. They are the author of Ugly Differences: Queer Female Sexuality in the Underground (University of Illinois Press, 2018) and the editor of Rated RX: Sheree Rose with and after Bob Flanagan (The Ohio State University Press, 2020). Some of their work also appears in American Literature; Social Text; Sounding Out!; TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly; The Journal of Popular Culture; and Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory. Howard is also a photographer whose work has been exhibited throughout California.

References

- Quoted in Julian Lucas, "Galaxy Brain," The New Yorker (10 and 17 July 2023), 34.[⤒]

- Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 2003), 63.[⤒]

- Samuel R. Delany, "DOUBLE VISION," Facebook, 2 June 2022. https://www.facebook.com/1467333757/posts/pfbid0bCDEbcydqxWmjnH6zi17nfuNqK9eE3563Ya4pEWTMhJBWk38HervTHQ8dWWX72jcl/?d=n[⤒]

- "Strabismus," Cleveland Clinic. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/15065-strabismus-crossed-eyes.[⤒]

- Robert Reid-Pharr, Foreword, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, 20th Anniversary Edition (New York: New York University Press, 2019), xiv.[⤒]

- Samuel R. Delany, "Discourse in an Older Sense," Outspoken Interview by Terry Bisson, The Atheist in the Attic (Oakland: PM Press, 2018), 101.[⤒]

- "Samuel R. Delany, The Art of Fiction, No. 210," interview by Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah, The Paris Review 53.197 (Summer 2011), 24. In the same interview, Delany continues to explain how he experiences his dyslexia "The closest metaphor I can come up with is that it's like being able to recognize hundreds of different faces but being incapable of producing any sort of likeness of any of them with a pencil and paper" (ibid.).[⤒]

- "Samuel R. Delany: Disability and Dhalgren," transcription excerpt from 16 February 2016 interview by Al Filreis, Jacket2. https://jacket2.org/commentary/samuel-r-delany-disability-and-dhalgren.[⤒]

- Fred Barney Taylor, Director, The Polymath or, the Life and Opinions of Samuel R. Delany, Gentleman (Maestro Media, 2009).[⤒]

- The Polymath or, the Life and Opinions of Samuel R. Delany, Gentleman, directed by Fred Barney Taylor (Maestro Media, 2009), Bonus Disc: Additional Delany Interviews, "Dyslexia," 08:12.[⤒]

- Samuel R. Delany, "Ash Wednesday," Boston Review 9 May 2017. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/samuel-r-delany-ash-wednesday/.[⤒]

- My thinking here is informed by queer theorists who have written extensively about subcultural space and specifically include discussions of TSR, TSB. In distinguishing 'queer space' from 'queer city,' Dianne Chisholm writes "[Q]ueer space designates an appropriation of space for bodily, especially sexual, pleasure. [. . .] Yet the extent of [queer spatial practices'] subversion is limited by the power grid and total domination by capitalist market forces," Queer Constellations: Subcultural Space in the Wake of the City (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 10. Jack Halberstam addresses the changeability and inconsistencies that mark queer spatial movement in TSR, TSB: "[G]eo-specific sexual practices [...] develop and are assigned meaning only in the context of the porn theater, and their meanings shift and change when the men leave the darkened theater and reemerge into the city," In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 13.[⤒]

- La Marr Jurelle Bruce, How to Go Mad without Losing Your Mind: Madness and Black Radical Creativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2021), 206.[⤒]

- My use of "crip" here aligns with queer theory that has made field-changing connections between "crip" and "queer." See, for instance, Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (New York University Press, 2006) and Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip (Indiana University Press, 2013).[⤒]

- Excess's association with difference has been and continues to be thoroughly explored both as a problem of racialized and sexualized representation and for its productive potentials in identifying contours of minoritarian aesthetics and politics. For excess and excessive-adjacent concepts in some of Delany's most excessive work see Darieck Scott's chapter "Porn and the N-Word: Lust, Samuel Delany's The Mad Man, and a Derangement of Body and Sense(s)," Extravagant Abjection: Blackness, Power, and Sexuality in the African American Literary Imagination (New York: New York University Press, 2010), 204-256; Kirin Wachter-Grene's discussion of the troubling of containment in Delany's Hogg, "'On the Unspeakable': Delany, Desire, and the Tactic of Transgression," African American Review 48.3 (Fall 2015): 333-343. For theories of excess in the context of black and brown female sexualities, see Jillian Hernandez, Aesthetics of Excess: The Art and Politics of Black and Latina Embodiment (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020); Amber Jamilla Musser, Sensual Excess: Queer Femininity and Brown Jouissance (New York: New York University Press, 2018); Nicole R. Fleetwood, Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2010).[⤒]

- The Polymath, 00:30.[⤒]

- The Polymath, 02:40; 53:54.[⤒]

- The Polymath, 01:46.[⤒]

- For a thorough and astute study of American literary masculinities, see James Penner, Pinks, Pansies, and Punks: The Rhetoric of Masculinity in American Literary Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), 2011.[⤒]

- Peter Galassi, Philip-Lorca diCorcia (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1995), 6. For an account that is critical of both diCorcia's and Delany's relationships to those they document see Ricardo Montez's chapter

"'Trade' Marks: LA II and a Queer Economy of Exchange," Keith Haring's Line: Race and the Performance of Desire (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), 68-71.[⤒]

- Samuel R. Delany, Times Square Red, Times Square Blue, 20th Anniversary Edition (New York: New York University Press, 2019), xix; Katherine A. Bussard, Unfamiliar Streets: The Photographs of Richard Avedon, Charles Moore, Martha Rosler, and Philip-Lorca diCorcia (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 168. For Bussard's comprehensive analysis of diCorcia's photographs in the context of his collaboration with Delany, diCorcia's processes vis-à-vis the architectural-spatial histories of New York, and diCorcia's related photographic work, see her book's chapter "Philip-Lorca diCorcia: Analogues of Reality," 139-189. See also Michael Fried's chapter "Street Photography Revisited: Jeff Wall, Beat Streuli, Philip-Lorca diCorcia," Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 235 - 259.[⤒]

- See José Esteban Muñoz's oft-cited writing on queer evidence: "[ . . . ] the ways in which we prove queerness and read queerness, is by suturing it to the concept of ephemera. Think of ephemera as trace, the remains, the things that are left, hanging in the air like a rumor," Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 65.[⤒]

- Delany, TSR, TSB, xxiv.[⤒]

- Photograph by Philip-Lorca diCorcia in Delany, TSR, TSB 59.[⤒]

- Delany, TSR, TSB, 58.[⤒]

- Valérie Jardin, Street Photography: Creative Vision Behind the Lens (New York: Routledge, 2018), 47.[⤒]

- Different yet related types of queer captioning are identifiable throughout Juana María Rodríguez's Puta Life: Seeing Latinas, Working Sex (Durham: Duke University Press, 2023). For instance, the book's dedication is a lengthy list of the first names, when available, of all the women discussed in the book.[⤒]

- Delany, TSR, TSB, xxiv.[⤒]

- Delany, TSR, TSB, 145-146.[⤒]

- Delany, TSR, TSB, 146.[⤒]

- Jolene Hubbs, "Writing against Normativity: Samuel R. Delany's Textual Times Square," African American Review 48, no. 3 (Fall 2015), 351.[⤒]

- Delany, TSR, TSB, 10.[⤒]

- The connections between "The Blues" and African-American culture and experience goes without saying. But I wish to cite here the exhibition Blues for Smoke, which I attended during its run at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 2012. Organized by Bennett Simpson, the exhibit included Fred Barney Taylor's documentary The Polymath or, the Life and Opinions of Samuel R. Delany, Gentleman (Maestro Media, 2009), which ran on a loop in the one the exhibit's galleries and was where I first saw the documentary. There is no mention of the documentary's display or inclusion in the Blues for Smoke exhibition catalog.[⤒]

- Muñoz, Cruising Utopia, 52.[⤒]

- Samuel R. Delany with photographs by Philip-Lorca diCorcia, "X-X-X Marks the Spot," Out (December 1996/January 1997), 115.[⤒]

- Bussard, Unfamiliar Streets, 158.[⤒]

- Bussard, Unfamiliar Streets, 139 -189.[⤒]

- The Polymath, 1:00:54. Also see Fred Moten's discussions of Delany's "'libidinal saturation,' which now we might be able to think of as what happens on the bridge of lost and found desire that stretches between seeing things and seeing absolute nothingness, where relation fades in fog and granite, or paper and plexiglass," Black and Blur (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 261.[⤒]

- Kenneth R. James, "Editor's Introduction," The Journals of Samuel R. Delany: In Search of Silence, Volume 1, 1957-1969, edited by Kenneth R. James (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2017), xxxi.[⤒]

- James, "Editor's Introduction," xxxi.[⤒]