Samuel R. Delany's Improbable Communities

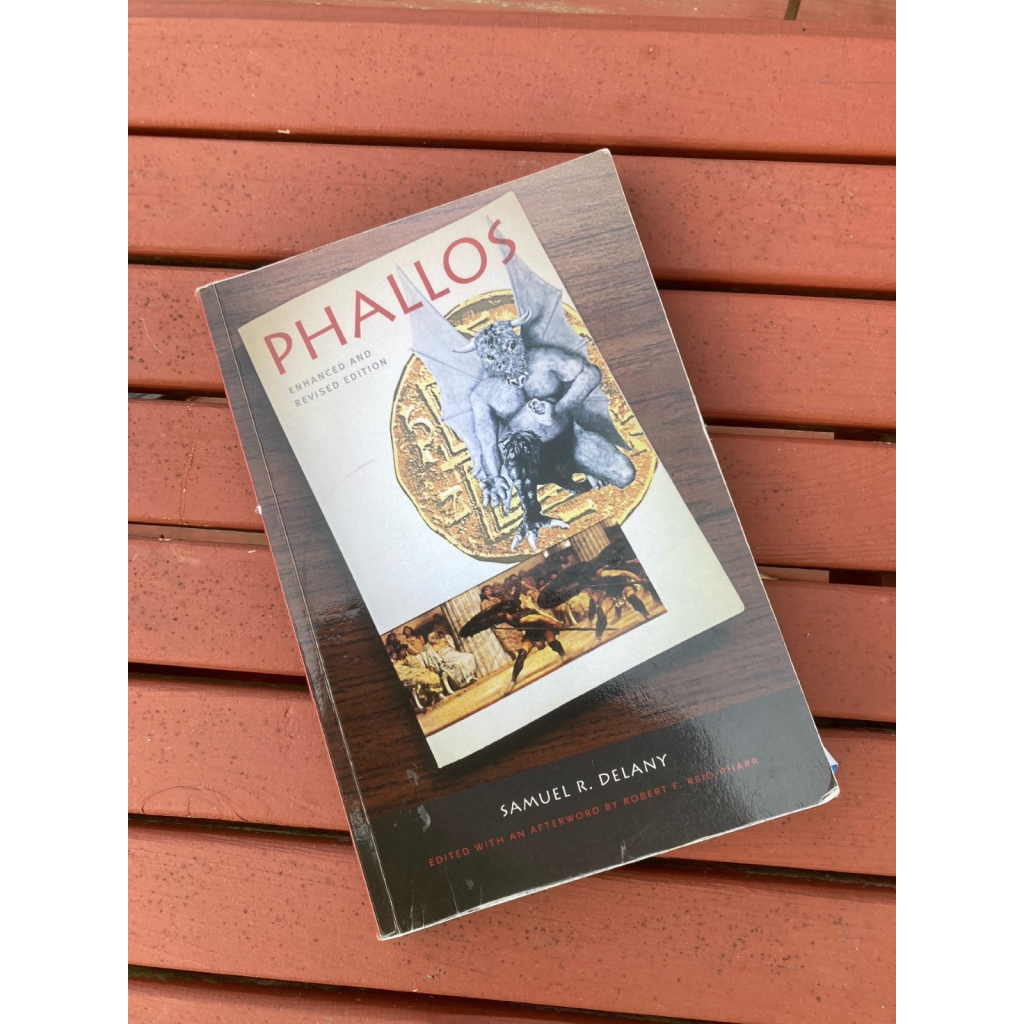

Author's note #1: On the cover of Samuel R. Delany's metafictional novella Phallos is a drawing of a winged Minotaur: head and tail of a bull, beclawed hands and foot, muscular human torso. Kneeling, he looks directly at the viewer, one hand extended palm up, the other curved inward against his breastbone, pointer finger touched to thumb, in a recognizable allusion to the ritual postures of ceremonial magic.1 This is the Nameless God worshipped in Hermopolis whose rumored reality haunts the novella's characters and whose statue's stolen phallos animates its plot. In the novella's story-within-the-story, the theft of the phallos by unnamed thieves sends the hapless protagonist Neoptolomous on his lifelong quest. In the frame story, it is the original of the book Phallos that has been lost and replaced by a heavily redacted synoposis. The copy sitting on my table is the 2013 Wesleyan University edition in which the novella is bookended by introductory and critical commentary. The cover design of this edition is composed of a photograph of the original placed as if left casually on a wooden end table. So while there is no labyrinth as such in the novella and while the Nameless God is never explicitly described as a Minatour, it is nonetheless the case that the book takes the form of a labyrinth whose underground passages tunnel across Delany's work, connecting this novella to Mad Man and Shoat Rumblin and on to the Neveryon series and from there to the whole of the Modular Calculus. This essay attempts to walk that labyrinth without a map to model the journey.

Author's note #2: The subject of the essay presented below is Samuel R. Delany's metafictional novella Phallos. The novella shares traits with many of Delany's favored modes: readers of his essays, criticisms, memoirs, and pornographic novels will find much that is familiar, from the meditations on class in Times Square Red, Times Square Blue to the unfinished manuscript conceit of Mad Man; characters or figures from Phallos show up also in Shoat Rumblin, Dark Reflections, and Through the Valley of the Nest of Spiders. Generically and in terms of its intellectual ambitions, however, Phallos is closest to his better-known fantasy tetralogy, Neveryon. As in that earlier series, Phallos explores the relationship of desire to signification through references to poststructural literary theory, specifically to the work of psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. For Lacan, the castration complex that initiates the Freudian Oedipal cycle applies to all instances of signification in which fully revealed meaning is both endlessly sought and endlessly delayed. Initiated by the substitution of the auto-erotic pleasures of childhood under threat of castration for the promise of a future as the law-giving father, the phallus engenders patrilineal succession as a legacy of phobic and insecure sons. Phallos tells the story of the phallos2 as pornography.

At the center of Samuel R. Delany's 2004 novella Phallos is the sacred city of Hermopolis, named after the Greek messenger god, Hermes, and dedicated to the worship of Thoth, Egyptian god of writing. Framing this main narrative is a brief legend about Adrian Rome, who has over the course of his life acquired and then promptly lost copies of the fictionalized pornographic text Phallos, which for Delany becomes a metafictional text-within-a-text. The closest Adrian ever gets to actually reading Phallos (and the version that forms the main text we read) is a bootlegged copy he downloads from a pornographic website. Unfortunately for salacious readers, the version Adrian finds has heavy redactions made by Randy Pedarson and his friends, graduate students at the University of Idaho, in an attempt to clean up the content for publication on a university webpage. The resulting edition substitutes summary for the more explicit sections, and appends chatty footnotes on everything from the relative hotness of the sex scenes, to their differences of opinion about what to keep and what to cut, to their speculations about whether or not to believe the textual history related in the Introduction to a now-lost Essex House edition.3 In Pedarson and company's comments, Phallos is described as a Greek antiquity owned by the art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, from whom it was stolen in 1768 by a teenaged thief and murderer named Francesco Arcangeli, whom Winckelmann met at an Inn, and from whose hands it passed to a veritable who's who of nineteenth-century luminaries, before finally being printed in subscription edition by an occult fellowship, The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. All of this, beginning with the classical origin of the text, the scholarly editors declare a hoax.

Lost texts, scholarly footnotes, a city dedicated to the god of writing: this is a novella about interpretation. As is true of much of Delany's prose fiction, Phallos is a philosophical meditation about the circuity of meaning and its relation to desire. So much of the work plays on well-known poststructural concepts and phrases that it seems almost to be a commentary in the form of a novella, its arch self-awareness evident in the title's allusion to Jacques Lacan's famous phallus-as-signifier. In these terms, the initiated reader would see the homophonic play between phallus and Phallos as an illustration of the more general condition by which no sign fully exhausts itself in semiosis, a point famously made by Jacques Derrida's coinage différance.4 Where the dream of communication (and also of desire) is to be received without remainder or lack, poststructuralism points out the gap or spacing that allows for signification as such, the irrecuperable difference that can't be enlisted into meaning but without which meaning can't emerge. The phallus then is like a scab that forms around the wound left by this realization, hardened into a fantasy image of what it would have to be to have mastered that gap and discovered its secrets. Wishing to possess the phallus — that which will allow perfect communion with a lover, full understanding of a work of art, total access to the world around us — sets in motion a comedy of covetous action bent on acquiring what can never be possessed because it doesn't exist as a thing in itself. That it is the male sex organ that signs this mistake is itself the mark of an error, the collapse of the circuit that distributes values with the thing most valued in the circuit's economy. Under these conditions, the penis is condemned to endlessly engage the laughable quest to be the Phallus, which isn't anything at all except this circuitry of errors itself.

Poor deluded phallus, poor deluded subject stuck in this tragicomedy of errors. Or perhaps not, for there is another error and another comedy this book puts into play. The initiated reader may see the allusions to Lacan and Derrida, but there is something ironic and hilarious about focusing on the phallus rather than the penis in what is, after all, a work of gay pornography. Critics have for the most part taken at face value the novella's own insistence that all the smut has been excised from the text, but this overlooks what is obvious on the page. The version of the text published on the web may not have the rhapsodic descriptions Randy cuts and then eulogizes, but even in this neutered state is it still a compendium of pleasures. If anything, in its circumspection and loquacity, it is like hearing about an orgy from someone who saw it through a dirty side window — and some people like that sort of thing!5 But this is not to make a pitch for a more naïve, less theoretically informed reading of the novella. Rather, it is to note the prominence of initiation as an important but overlooked theme in the novella's metafictional play. What is seen and what is hidden, from whom and by whom, seems closely connected not only to the questions of sexuality and pleasure but also to that other easily missed topos: the occult, which in this novella is closely associated with writing.

In his 1978 work Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture, Arthur Evans cites psychoanalyst Thorkill Vanggaard's 1972 study Phallos: A Symbol and its History in the Male World to explain the story of Emperor Hadrian and Antinous, the "gay god" to whom Hadrian raised a shrine after Antinous's untimely death at 19 in 130AD. For Evans, the period between the death of Socrates in 399BCC and the establishment of Christianity in 313AD with the Edict of Milan was a period of decline in which homosexuality lost its religious and civic status and became instead a private matter. "To Hardian the relationship with Antinous was a personal matter," writes Vanggard, "It was not institutionalized any longer, had no place in the cult, and its symbols had ceased to be generally recognized expressions of the noblest aims of the communal life of the society."6 Whatever the historical accuracy of these claims, whether Delany intended to cite these works or not, they form a telling background to the work's metafiction. Darieck Scott, one of the few critics to address the role of magic and the occult in Delany's writings, argues that the occult in the novella helps to bring out the "nameless and monstrous" inner self connected with the anti-social imperatives of the drives against the "false self, not-self" of our imaginary ego-projections.7 This reading fails to reckon with the intensely social and indeed economic effects of the novella's rites of initiation. As magic is associated with writing on the one hand and initiation on the other, the novella's carefully constructed metafictional artifice enacts a magical counter-history in which social, economic, and sexual ties between generations of gay men secretly continued.

***

If the sidelong seductions of the phallus were to appear in fictional form, they might look like the near-misses and way too exact hits of the book's textual origin story with its references to Plato, Walter Pater, and Aleister Crowley, even to "an elderly Black man of letters" — clearly a figure for Delany himself.8 The work as a whole moves in this way. It is composed of several plotlines, each of which lays over the other in an intricate filagree of repetitions, inversions, and refractions. The original manuscript is almost comically slippery, falling out of and into possession, first as a priceless antiquity and then in the versions Adrian finds and loses again. The synopsis edition begins the text proper only after first taking several pages to recount this origin story and then digresses after half a sentence into a lengthy footnote that translates the text's opening epigraph, a fragment in Greek from the pre-Socratic Anaximander, and then glosses its relevance to nineteenth-century philosophers, cutting off the main text at half the page length. Periodically, this extraordinary interruption is itself interrupted to include one of the other editors' snarky emendations. In this veering fashion, the editors build up layers of description and commentary.

Within this ornate patterning, it is the theme of movement that stands out the most strongly. The book's innermost narrative follows Neoptolomus, who travels nearly as much as the frame story claims of the book itself. Born in Egypt, he spent his orphaned boyhood as a servant in the house of a Roman nobleman named Lucius, who takes on Neoptolomous as his lover and successor, buying him a commission in the Roman army and then employing him in his business. In that role, Lucius sends Neoptolomus to purchase land owned by the priests of the Nameless God in the town of Hir-Wer across the Nile from the bustling city of Hermopolis.

Neoptolomus arrives in Hermopolis during the autumn celebration of Thoth and is soon disoriented by the rain and the crowd of revelers. As he ambles along the warehouse district, he finds himself walking behind an attractive and clearly sexually interested young man.9 The two find an unused stockroom and are soon engaging in creative and strenuous sex from which Neoptolomus awakes to find himself alone. Again on the street, he falls into conversation with an older man, apparently quite learned despite his beggar's rags. This man relates that he is looking for his lover, whom he was meant to witness seduce the first out of towner he chanced to encounter. Spying on such scenes, the ersatz-beggar explains, is his delight and the delight of his young lover to create. As the two walk, lost in conversation, they stumble into a street fight. In the middle of the melee lies the bleeding body of the young man with whom Neoptolomus recently passed a few hours, hours which the older man had been hoping, fruitlessly, to enjoy from the shadows. Clearly now, the bit of sexual theater in which Neoptolomus unwittingly played his part was engineered for the delectation of the same man with whom he had been conversing, and who now in his grief has thrown off his threadbare cloak and revealed the lustrous raiment beneath it.

The series of grisly but comic coincidences continues when Neoptolomus's companion in the army, now a temple priest, appears at the edge of the crowd and rushes him to the very place he had been seeking all along, the Temple of the Nameless God, where they are taking the body of the murdered young man, now revealed as Antinous, lover of Hadrian, Emperor of Rome, whose sexual escapades were legendary. Much later in the narrative, Neoptolomus learns that this was no random murder. Antinous had been selected by Hadrian to fulfill a rite to the nameless god. Every spring, an adherent may learn the mysteries of the phallos, provided that he make a large donation to the temple and supply a human sacrifice who, for a year and without knowledge of the rite's bloody conclusion, will be lavished with attention and surrounded by luxury. When the spring of Antinous's sacrificial year comes around, however, Hadrian is unwilling to fulfill the contract. Instead, he begs the priests to give him a few more months and a death of his choosing for his beloved in exchange for a large cash donation. Expecting to witness a scene of sexual indulgence, then, Hadrian instead stumbles into the murder he himself commissioned. And Neoptolomus, scripted as a bit player in the cuckolding fantasies of an emperor, finds himself an unwitting bystander to an event whose significance will only become clear years later.

Or so he presumes, and the reader with him. Unworldly, in a new city, and with a youthful willingness to accept the truth of appearances, Neoptolomus leaves the grand events to others and focuses on his commission. Once at the temple, however, they learn that Antinous's murder was not the only loss that day: someone has stolen a sacred religious artifact, the phallos of the nameless god, at the same time that Antinous was being stabbed to death. In fact, Neoptolomus is certain that the killer is there in the temple hall with him, now wearing the cast-off disguise of the Emperor. Ignoring all this and ignoring also his arousal at the sight of the murderer's imposing frame and scarred face, Neoptolomus attempts to conduct his business, entreating the priest to accept his offer to buy the land in Hir-wer on behalf of his patron. This the priest resists: he is sympathetic but firm that they can do no business until the thief has been caught and the phallos returned to the temple. In small compensation, however, they offer Neoptolomus a room for the evening. There, in the early morning hours, he is awakened and told that he has narrowly escaped becoming the temple's next human sacrifice to the unnamed god by the donation of the scarred murderer, with whom he will now travel as an indentured sexual servant, and who the temple priests have entrusted with the task of recovering the phallos.

***

Two losses, two donations, two sacrifices — one greater, one lesser, like the crosstown temples to Hermes and to the Nameless God. The two stories mimic each other, the mythic and the quotidian. As above, so below. This phrase, familiar even to the occasional consumer of occult and new age wisdom, comes from the Hermetica, a corpus of text by the semi-mythical Hermes Trismegistus. It means that the sublunar world is composed of emanations of the celestial and so material things are connected through sympathetic bonds to the divine.10 Recovered in the 15th-century, the Hermetica was translated by Marsilio Ficino alongside rediscovered works by Plato as a part of Cosimo de' Medici's Platonic Academy, an important locus of Renaissance humanism. Originally thought to be of ancient Egyptian provenance and therefore as presaging Christianity, the works were actually of Greek authorship and composed much later, in the first few centuries of the common era, a time in which Hermeticism, Neoplatonism, Christianity, and Gnosticism were merging with and emerging from each other. (And, of course, it is also the time of Hadrian and Antinous.) Of these, it was the Gnostics who contributed the licentious character to modern occult practice. For the Gnostics, the world reflects the divine, but that divinity is not the true God but rather a Luciferianesque false creator-God (or demiurge), who stole the pure idea of Man from the mind of a Nameless and Unknown divinity. The Nameless God, however, took mercy on the false creations and imbued them with spirit. In their quest for spiritual knowledge, or gnosis, Gnostics believe that they must exhaust the seductions of the material world in order to remember that which lies beyond it and from which the soul is composed. Their orgiastic rites were intended to flout all laws and institutions, which were born of original deception from which the world cannot be redeemed.11

Over the centuries, the Hermetic and the Gnostic currents of esoteric thought have threaded through each other and acquired strands from spiritual techniques like Tantra.12 Seeking that which cannot exist in this world and cannot be known through rational thought, the modern occult practitioner uses trance, sex, and drugs to escape from the world and into the more knowing interior self. At the same time, this movement to the interior focuses the practitioner's will, which can then use the energy produced from sex, meditation, or ecstatic dance to animate a magical act. Picking up yet another strand, the influence of Freemasonry (which formed the basis for twentieth-century esoteric societies such as The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and the Ordo Templi Orientis with its central ritual, the Gnostic Mass) gave most contemporary esoteric organizations an initiatory structure. In the Scottish Rite, there are thirty-three degrees each with their own secrets and rituals of initiation and it is only once an apprentice has passed through the levels that it is possible to understand the hidden logic of the whole. In Aleister Crowley's Ordo Templis Orientis, the secrets of the highest degrees are the secrets of sex magic.13

***

The remainder of Delany's novella focuses on the quest for the phallos, first by the murderer, who neither find it and nor evinces much interest in looking for it, and then by Neoptolomus, who can't shake his fascination with it. Off and on for the next fourteen years, Neoptolomus will hunt the phallos, following whispers from back alleys to a hermit's mountaintop haunt. Sometimes it seems that the phallos eludes him by inches or moments, other times that it is merely rumor and not a physical object at all. In one noteworthy incident, he was himself the origin of a tale that returned to him as if it were an eyewitness account, almost but not wholly in the form in which he originally told it. Once he even finds himself in possession of the phallos but, convinced that he is holding only a poor copy, he flings it to a crowd of street revelers. This quest to recover the missing artifact is never his only reason for what he does; he is first and foremost a merchant and it is only when his economic interests coincide with his curiosity that he allows himself to indulge his obsession. At each destination, though, word of it is there — in Rome, in Syracuse, in Hermopolis, at the foot of Mount Etna — and although he travels widely, the people he encounters turn up again and again. The same person is beggar and Emperor, or solider and priest, or friend and thief - even, in the work's most tellingly artificial twist, the very same brigand who murders Antinous and purchases Neoptolomus also serves as guide for the young man, Nivek, who will become Neoptolomus's partner and to whom, apparently on a whim, he recounts his role in Antinous's murder.

The story Nivek hears bears directly on the meaning of Neoptolomus's life. Though sworn to tell no one this "secret history," Nivek nonetheless confesses the whole encounter to Neoptolomus. "When I first came on my mission from the Chiefs of the Seven Great Tribes," he relates, "I required a guide north across the dunes." The man he finds describes himself as having once been a bandit "about a decade and a half before," and had such peculiar markings ("six rings in one ear — and the lobe of the other was a fleshy loop from which, he told me, a grooved gold nugget had long since fallen" "rings too in his dugs") and such remarkable physical attributes ("extraordinarily fleshy foreskin stretched to inordinate lengths"; "right cheek deeply scarred"; "blind in one eye") that he is revealed, even before he tells the story, as the same man who had purchased Neoptolomus.14 The story Nivek tells Neoptolomus is the same one we have already witnessed: the great love between Antinous and Hadrian, the plea for six months reprieve and an easy death, even the scarred bandit paid by the Emperor to make the death look like an accident ("The emperor took my robe from me and wore it — since, as he said, he was the young man's true murderer").15 The tale has now become legend in the fifteen years since Hadrian deified Antinous and raised a temple to him in Hir-wer:

Have the tales of Antinous and the Emperor Hadrian reached into the Ethiopian pampas? Well, if you have even heard their names, perhaps this story will mean something to you — though it is a secret history you must never tell another soul. Be glad you go in autumn, for the temple rituals of that time of year, though horrible and inhuman, are easily circumvented with a little luck and money. The rituals of the spring, however, are much more virulent, far more powerful, and of a cruelty that dwarfs their autumn rehearsal. [ . . . ]

As the nameless god takes from you the victim, whom, for a year, you have worked to supply with every possible pleasure, there you will learn the true and agonizing mystery of the phallos — for there you will face the dreadful absence, uncloaked and unmitigated, at the center of all and everything.16

Where the original account left unstated the link between the murder and the theft of the phallos, this new version reveals the motivation that ties them together.

I stabbed him in the neck during the street brawl, manufactured to distract any passing witnesses, there in a Hermopolis alleyway — and took back my garment.

The emperor had the boy's body taken across the water to Hir-wer — now the city of Antinopolis — because, though the mysteries forbade his return to Hermopolis, Hadrian wished to consecrate the place of the boy's death. For, you see, men in the emperor's employ had already fallen on the temple and stolen the phallos away — and for years the minions of the temple endeavored to wrest it back, while the emperor's forces moved it hither and yon, in an attempt — not always successful — to keep it out of their hands.17

What appeared in Neoptolomus's first-hand account to be a series of striking coincidences whose world-historical implications were also of personal importance instead turns out to be a series of carefully arranged appearances, like the sexual displays Antinous manufactures to please Hadrian's taste for voyeurism. Much of this explanation, however, rests on a funny little semantic gap, the phrase "for, you see" in the middle of a paragraph, bridging an unstated cause to a very definite effect. What purpose was served by the emperor's theft of the phallos? Revenge for the death of his beloved? Desire to know the mysteries he had been denied when he refused to give Antinous as a sacrifice? "For, you see," presumes rather than shares knowledge, and so appears to be another instance of the phallos, another absence that invites overfilling with hypostatized meaning — which is what the bandit precedes to do. For, he continues, Hadrian acted against the temple in precisely the manner the temple contrived for him to do: "Again and again the agents of the temple of the nameless god pretend to be far more powerful than they are, now luring the truly powerful to steal the phallos for them, then maneuvering the powerless to steal the phallos from them."18 In Hadrian's decision to raise the new temple to Antinous, the priests of the nameless god fulfilled their long-held desire to have their temple "on the outskirts of a great city," rendering the whole history an elaborate real estate transaction.19

This real estate transaction is of course is why Neoptolomus came to Hermopolis at all - to buy real estate in Hir-wer for his patron, Lucius - and so the reason why he was at the scene of Antinous's murder, from which he was brought to the temple, and so why he was subsequently purchased by the scarred brigand. This series of revelations ends with the brigand musing that he himself believes the phallos was thrown into Mt. Etna by a "renegade hunchback priest,"20 the same aged hermit with whom Neoptolomus spent an uneasy (though sexually satisfying) few days, the same hermit who (the brigand causally reveals) had many years prior purchased him during the autumn rites from the priests of the nameless gods. It is also, we learn a page later, how Nivek came to be purchased by Neoptolomus. "Though we tarried a season at Sais," Nivek concludes, "and stopped by the statues of Memphis, at last he left me at Hermopolis, where I had already seen across the water that my mission to invest in Hir-wer was now sorely compromised, for Hir-wer was no more . . ."21 Of course, Nivek accepts the hospitality of the temple (this despite having heard the stories from the bandit) and it is in those circumstances that he meets Neoptolomus, returned to the temple to witness the installation of Clivus, his old friend from his soldiering days, as High Priest of the temple on the autumnal celebration of Thoth. Wiser now, Neoptolomus recognizes that he is witnessing a ritual when Nivek implores Clivus to complete the commercial transaction he has been entrusted to undertake and Clivus replies that no commerce can happen until the phallos — stolen that very day — is returned. But he is not so wise that he is not caught up in the horror when Clivus tells him that Nivek will be the temple's sacrifice as he was "the first stranger to the temple who approache[d] us in a commercial quest." He continues,

At midnight, a group of our priests, helped by hired ruffians, will drag Nivek out, take him to that basement hypogeum, where, in chains, doubtless thinking he is in the midst of a horrifying dream, he will face that terrible object, black with the blood of a thousand murders. In that chapel of black stone, with chains turned on wooden wheels, he will be hoisted into the air by his wrists and ankles, then lowered onto the actual, material, and sacred phallus, its metallic tip introduced into his fundament.22

Horrified, Neoptolomus quickly agrees to pay the thirty dinars that will free Nivek and replace him with a sacrificial beast, recalling, even as he gives the money to the priest, a dozen years back when his bandit savior roughly cajoled that he had cost him "thirty silver dinars — and a night's sleep!" He does not quite remember, however, his own patron's remark when, as a very young man, he protested that buying property in Hir-wer seemed like a poor investment.23 His "true motive," his patron confessed at the time, was not commercial at all; rather, "he wished to repay an old debt to the temple priests."24

While the bandit's conspiracy tale never really amounts to more than conjecture, and while the horrifying rites of spring never appear at all, these autumn rituals — the naïve young man sent to fulfill a commercial transaction, threatened with sacrifice, and redeemed in sexual servitude — are an indisputable fact of the narrative. Taken together, they form a genealogical chain: hermit to bandit to Neoptolomus to Nivek with another line of succession intersecting around Neoptolomus patron's patron to whom he repays his debt by sending Neoptolomus to the temple. Very unexpectedly, then, given the association of the phallus/phallos (both in and out of the text) with the circuitry of lack and the arbitrariness of the signifier, the story-within-the-novella ends as if it were a straightforward bildungsroman of a young man whose buffeting from place to place was intended from the outset to bring him back to where he began. And indeed, in the final chapter, Neoptolomus returns to his patron's estate, now a sophisticated adult fully at ease in his surroundings, to receive word of his inheritance. The succession story is not exactly one of patrilineation since these are chosen relations of affinity rather than obligatory blood ties. But neither is it random or for that matter wholly self-selecting. The novella occasionally invokes the "only gods truly great . . .. that rambunctious pair, Muddle and Need"25 and while that seems to be true of the Neoptolomus's perspective, which is often muddled, it is definitely not true of the succession plot. Coincidences abound, but they are all carefully constructed artifices in what finally appears as a ritual of sexual tutelage aimed at queer reproduction.

Occult queer reproduction. This book, a work of fiction, is about a book which is also a work of fiction: a fictional hoax. The occult is full of such hoaxes that boot-strap themselves into existence by writing themselves into or making up whole traditions post-dated hundreds or thousands of years in the past: the history of masonry, the conspiracy against the Templars, the Egyptian origin of the tarot, the pre-Mosiac origins of the rediscovered sixteenth-century corpus of Hermes Trismegistus. Thoth, a minor Egyptian deity, is most familiar in the Western tradition through the tale Plato has Socrates invent as an instructive parable of the duplicitous power of writing, causing his interlocutor Phaedrus to rebuke him: "Yes, Socrates, you can easily invent tales out of Egypt."26 But this is a mistake — Phallos is nothing if not elaborate in its structure and ornate in its hidden correspondences — just as it is a mistake to focus too intently on the phallos and the phallus, the gap and its secrets (even the secret of its lack of secrets), which like the muddle in which Neoptolomus finds himself, obscures the things that are present, including first and foremost the rituals that secure a gay lineage of pleasure and profit. If, as the novella has it, the phallos is a "marker in a plot of plottings that web together the material world, an extraordinary fiction disseminated over the land to net a host of other fictions of power"27then its invention is no easy thing at all. It must be carefully constructed, fitted to what it hopes to accomplish, and able to travel widely and flexibly without losing its potency. Not for nothing is this also a book about market forces set in motion by a real estate transaction.

Neoptolomous is a trader, someone who traffics goods and currency with at least implicit awareness that the value isn't in the object or the amount that it commands but in the swap between the two and so must circulate to be maintained. But this system of exchange which distributes wealth and poverty across the necessary (phallic) gap grounds itself in a hoax, a necessarily flexible and tenacious fiction, called currency.)) Playing the role scripted for him, Neoptolomus finds himself a part of an occult history that collapses past and future, cause and effect, catching up his own life in its plot:

A paragraph in the old Roman's will [ . . . ] still troubles Neoptolomus; for it, too, suggests that, from an autumn visit to Hermopolis in his own youth, when something unspeakable occurred that was nevertheless the start of his climb to wisdom and wealth [ . . . ], Neoptolomus's patron had long been aware of the desire of the priests of the nameless god to have a city raised on the site of Hir-wer, years before the birth, much less the death, of Antinous.28

The sexual revels that make this a work of pornography — Neoptolomus by himself, with another, in a group, sometimes anonymous, sometimes in committed bonds, sometimes with a youth of the type he once was, in every conceivable way, with every possible orifice and secretion — are all, from his first orgasm in his patron's house, at the service of this occult history.29 For there is another error here. To write about this book and not mention the sex seems like its best and least appreciated joke. It is a mistake the book all but dares us to make: to be as little randy as Randy, to speak of Lacan rather than Hermes, is to be caught up in the novella's manipulations as surely as Neoptolomus played his role in the ritual of the Nameless God. The conviction that there is no hidden truth except the truth of lack very effectively obscures what is otherwise obvious: this is a book about dirty, fervid, consuming phallic worship devoted to the magical reproduction of exuberant queer life.

Rebekah Sheldon is Associate Professor of English at Indiana University Bloomington, and is the author of The Child to Come: Life After the Human Catastrophe (University of Minnesota Press, 2016). She has published work in: E-Flux; Science Fiction Studies; Configurations; Rhizomes; Stanford Arcade Colloquy: We, Reading, Now; and Science Fiction Film and Television; and the Cambridge Companion to American Science Fiction, among other venues. She is currently at work on a new project, We Sorcerers: Magic as Method, which is about occult and supernatural figures in the critical tradition.

References

- Compare this drawing to the Hierophant card in the Thoth tarot deck[⤒]

- This essay uses "phallos" when referring to the idea of the phallos as it relates to the novella's plot, and uses "phallus" when discussing Lacan and the broader psychoanalytical apparatus surrounding the phallus.[⤒]

- Both of which makes the text more of a commentary with lengthy quotations from the original than a scholarly edition per se.[⤒]

- The import of this replacement of Jacques Derrida's difference/différance homophone with phallus/phallos will be clearer later in this essay, though I might note here that the slant rhyme between homophone and homophile also seems newly meaningful in its light.[⤒]

- The critical essays included in the enhanced and revised edition from Wesleyan University (its own small irony is that it has been published by a university press!) generally come out on the side of pleasure as well, seeing the charm of the book in its attention to the superfluity that emerges from lack. As Steven Shaviro points out, the phallos in this novella enables "a deficit and with a surplus . . . an excess of possibilities" for which the phallos is more or less a Hitchcock-style MacGuffin. (Steven Shaviro, "Ars Vitae: Delany's Philosophical Fable" in Phallos: Enhanced and Revised Edition, ed. Robert Reid-Pharr (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2013), 166.[⤒]

- Rhorkill Vanggaard, quoted in Arthur Evans, Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture (Boston: Fag Rag Books, 1978), 56.[⤒]

- Darieck Scott, "Delany's Divinities," American Literary History 24 no. 4 (Winter 2012), 720.[⤒]

- The novella also continues a line of works in the gay male canon that link homosexuality to magical and occult forms and especially to Teleny, the pornographic telepathy novel attributed to Oscar Wilde. My thanks to Patrick Kindig for pointing this out to me.[⤒]

- "We are in a storm at the Hermopolis docks on the day of the September equinox ... Despite the wind and rain, the revels of the city's titular deity, Thoth, fill Hermopolis's main streets and squares with processions" (22). Almost all of this is true to the historical record; these are real places and characters. A rainy fall day, however, is unlikely in Egypt. It's an odd off detail that aligns the scene far more strongly with New York's Chelsea piers in the late 80s than to 1stC Egypt.[⤒]

- Antoine Faivre, Access to Western Esotericism (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994). On sympathy, see Faivre 10-11; on the Hermetica, see Faivre 58-59.[⤒]

- Jacques Lacerriere, The Gnostics, Trans. Nina Rootes (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1989), Lacarriere 67-69.[⤒]

- On the influence of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam in Western Esotericism, see Hugh Urban, Magia Sexualis: Sex, Magic, and Liberation in Modern Western Esotericism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).[⤒]

- Aleister Crowley gives a sense of these sex magic rituals in The Best of the Equinox, vol 3: Sex Magick (San Francisco: Red Wheel/Weiser, 2013).[⤒]

- Delany, Phallos (repr.; Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2013), 110.[⤒]

- Delany, 112.[⤒]

- Delany, 110-11.[⤒]

- Delany, 112.[⤒]

- Delany, 112.[⤒]

- Delany, 110.[⤒]

- Delany, 112.[⤒]

- Delany, 113.[⤒]

- Delany, 91.[⤒]

- Delany, 94.[⤒]

- Delany, 20.[⤒]

- Delany, 27.[⤒]

- The whole tradition is a prime example of hyperstition before that concept was framed, including Jacques Derrida's reading of it in Dissemination.[⤒]

- Delany, 79.[⤒]

- Delany, 114.[⤒]

- The novella ends with a brief return to the frame story in which Randy speculates about who might have written the now-lost pornographic edition, naming a virtual who's-who of queer and experimental science fiction writers, but the very last word is given to Randy's friend Binky who laments the way Randy overlooks the many women in the text. Even as the text is ending, in other words, it throws out shoots to other branches of the family tree as it undoes its own presumption of clear patrilineation.[⤒]