Issue 10: The Inaugural Prize Issue

But what a spiral man's being represents! And what a great number of invertible dynamisms there are in this spiral! One no longer knows right away whether one is running towards the center or escaping.

— Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space1

"Reeling and Writhing of course, to begin with," the Mock Turtle replied...

— Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland2

The figure of a spiral line leaps into Art Spiegelman's self-portraits after his modern masterpiece, Maus, making its inaugural showing in the comics-form introduction and illustrated afterword to Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*! (2008), Pantheon's thirtieth anniversary re-issue of the cartoonist's first collection of underground-era work (itself reissued in 2022). The present essay makes three basic arguments in relation to Spiegelman's deployment of this turning and returning image — a discursive spiral in three arcs. The first arc proposes Spiegelman's spiral as an emblem for the comics form, which underlines its plastic "being" or ontology as continuous transformation and co-mixing. The second arc moves to situate Spiegelman's comics form in relation to larger, longer histories of modernist aesthetics. Reading the resonances of Spiegelman's spiral backwards through twentieth-century literature and the visual arts suggests his pages as cells of modernist formal experiment after modernism. The third arc switches back to (re)examine Spiegelman's spiral as a ploy for his Mom's attention, not MoMA's. The form of Spiegelman's spiral may be an abstract line, but it cannot be purified of the context of its autobiographical origins. From this standpoint, the spiral's dynamic form morphs again to embody the continual oscillation in Spiegelman's work between filiation and affiliation. In Spiegelman's spiral, abstract form and filial feeling rotate around and around each other.

According to critic Edward Said, modernist literature broadly enacts a dialectical spiral of filiation-affiliation-filiation, which is instructive for understanding the ambivalent dynamics of Spiegelman's work. In "Secular Criticism," Said uses "filiation" to refer to the sum of original cultural associations (including "birth, nationality, profession") from which exilic modernists remove themselves in becoming modernist artists.3 "Affiliation" designates the network of associations the modernists consciously adopt to replace those of the filial orders, including "social and political conviction, economic and historical circumstances, voluntary effort and willed deliberation."4 For Said, the move from filiation to affiliation is neither complete nor linear; just as the word "filiation" echoes verbally in the word "affiliation," so traces of the original filial orders continue to echo through the orders of affiliation:

What I am describing is the transition from a failed idea or possibility of filiation to a kind of compensatory order that, whether it is a party, an institution, a culture, a set of beliefs, or even a world-vision, provides men and women with a new form or relationship, which I have been calling affiliation but which is also a new system. Now whether we look at this new affiliative mode as it is to be found among conservative writers like Eliot or progressive writers like Lukacs and, in his own special way, Freud, we will find the deliberately explicit goal of using that new order to reinstate vestiges of the kind of authority associated in the past with the filial order.5

Spiegelman becomes self-consciously modernist by dissociating himself from his traumatized family household — moving to San Francisco to join the then-thriving underground comix scene, for starters — and affiliating his work with the international and cosmopolitan movement of modernism in high literature and the arts. But if Spiegelman's enabling self-identification with modernism buys him distance from his family, and perhaps also from the overwhelmingly Jewish immigrant community of commercial cartooning, his avant-garde work also circles back to family history as the obsessional (if not always explicit) object of address in his work. The interrelation between the artist's modernist affiliations and his filial commitments, the push-pull of forces that drives his work, finds coded expression in the spiral form.

A few words about my approach. By situating Spiegelman's comics in relation to modernist practice, perhaps even as modernist practice, this essay contributes to a recent but substantial tranche of scholarship on comics and/as modernism.6 Over the last two decades, with the rise of the New Modernist Studies and the institutionalization of Comics Studies, scholars from a wide range of disciplinary backgrounds have begun to map out the historical, cultural, and aesthetic overlaps between the comics medium and the twentieth-century avant-garde. According to comics expert Hillary Chute, what we might consider comics' "high modernist" moment actually happened in the late 1960s and 1970s, during the "underground comix" movement based out of San Francisco. "It did feel like this must have been what the cubists were going through," Spiegelman has commented. "All the magic of being in Paris for the postimpressionist moment did somehow feel like being in San Francisco in the early 1970s."7 This parallel or analogue exceeds the transgressive dalliance of high art icons in the cultural gutter, as in Picasso's well-documented interest in The Katzenjammer Kids or Francis Picabia's affinity for Rube Goldberg. As Chute explains, comics' salient connection to modernism has to do with the politics of form. "Comics is a medium that is deeply formalist," she writes, "consistently revealing the imbrication of the aesthetic and the political in a way that marks its investments, even in the current moment, as aligned with modernist belief in the force of form."8 Taking up Spiegelman's pre-Maus career, including the strips included in Breakdowns, Shawn Gilmore traces the cartoonist's deployment of "the key modernist aesthetic of formal juxtaposition to jar and unsettle, while simultaneously drawing out new connections by means of ... visual parataxis."9 Of Spiegelman's solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in December 1991 and January 1992 — an exhibition showcasing the final draft pages of both volumes of Maus, alongside drafts and reference materials — Gilmore suggests that "Spiegelman's archive emerges as a unified modernist space...in much the same way Benjamin's The Arcades Project dissolves in an unfinished synthesis that privileges radical fragmentation over linear meaning."10

Now, readers familiar with Spiegelman's Maus — his graphic memoir about his parents' experiences in Nazi-occupied Poland and transgenerational Holocaust trauma — may be surprised to hear of Spiegelman's modernist influences and allegiances. After all, Maus's self-reflexive, metafictional strategies earned Spiegelman the sobriquet of a "postmodernist" author.11 The Norton Anthology of Postmodern American Fiction includes an excerpt from Maus, and Linda Hutcheon dedicates her essay, "Postmodern Provocations," to discussion of the same.12 Even acclaimed historian Hayden White writes approvingly that Maus manages to "raise all the crucial issues regarding the 'limits of representation' in general," making it a paradigmatic example of postmodern historiography.13 But I am not particularly interested in establishing once and for all whether Spiegelman is more modern or postmodern, nor is my aim to shoehorn Spiegelman's career into a recognizable historical narrative. (That story might go like this: Spiegelman's engagements with modernist aesthetics pre-Maus give way to the historiographic metafiction of his masterwork.) Rather, I wish to highlight precisely how Spiegelman's larger oeuvre seems to resist our ready taxonomies.14 If anything, the promiscuous periodization of Spiegelman's work since the cartoonist's arrival in the bright lights of literary respectability testifies to the enduring relevance of that work — the way it seems to speak directly to the most pressing concerns of the times, even now.

So why spirals? Tracking Spiegelman's signature spiral motifs leads us to see where and how Spiegelman's formalist playfulness articulates with the somber history of violence and psychological pain to which Maus bears witness. I recruit the spiral to think the entanglement of formal play and filial affect that stamps Spiegelman's production across decades — an entanglement that itself recalls modernism. Ultimately, thinking with and in spirals allows me to see and to name the dialectical identifications and disavowals through which Spiegelman's oeuvre at once recalls modernism and affirms its lively legacy in the contemporary.

Metamorphoses of the &/[Squiggle]

The spiral line is about as simple as they come. If you give a young child something to write or draw with — young children, like cartoonists, do not differentiate between writing and drawing — they will likely draw a continuous circling line. At the outset of his celebrated biography of Pablo Picasso, Sir Roland Penrose certifies the claim with reference to one particular child:

One passion above all dominated Pablo from infancy. His mother was fond of telling how the first noise he learned to make, 'piz, piz', was an imperative demand for 'lapiz', a pencil. For hours he would sit happily drawing spirals, which he managed to explain were a symbol for a kind of sugar cake [he] called 'torruella', a word formed from a verb which means to bewilder or entangle.15

In his essay, "Metamorphoses of the Vortex: Hogarth, Turner, Blake," W.J.T. Mitchell reminds us that the simple spiral is bewildering indeed: not a single form at all, but rather "a family or group of forms that describes a continuous series of transformations ranging from two-dimensional S-curves to cylindrical helixes to conical vortices."16 Different images from this geometrical family have distinct and sometimes contradictory connotations and emotional associations. What could possibly unite the upward thrust of a "spire" (etymological root of the word "spiral") in architecture; the destructive forces of a whirlpool or maelstrom; the mysteries of the DNA molecule; the feeling of getting caught in a depressive thought spiral; the meaningless ornamentation of a foliate design?

A pattern of movement characterizes the spiral across its great variety. As Nico Israel summarizes, the OED defines "spiral" as a "continuous curve" that swerves around to produce levels of distance from — or proximity to — a fixed point. One does not necessarily know which direction, towards or away from that originating point. As we shall see, this bidirectionality or ambivalence (up or down, toward or away, inward or outward) is key to the spiral form's vibrating complexity and semantic restlessness.17 In this chapter's first epigraph, for example, Bachelard invokes the spiral and its "great number of invertible dynamisms" to express an oscillation at the center of being: "if we want to determine man's being, we are never sure of being closer to ourselves if we 'withdraw' into ourselves, if we move toward the centre of the spiral; for often it is in the heart of being that being is errancy. Sometimes, it is in being outside itself that being tests consistencies."18 The spiral, for Bachelard, captures the paradox of an inside/outside dualism that can be pulled inside out.

But where Bachelard privileges spiral form as a metaphor for being, not all spirals are so tendentious. In fact, Mitchell argues that "the image of the spiral is so ubiquitous in art and nature, so flexible in its manifestations, that the form is quite capable of becoming absolutely banal, a merely decorative, ornamental device devoid of special meaning or content."19 On one hand, Spiegelman's spiral lines are "only lines on paper, folks!!" as Robert Crumb put it in his memorable parody page and comics manifesto.20 "Only lines" emphasizes the mark as simple, easy, abstract, without significance or reference. "That [Crumb's parody page] seemed really profound to me at a certain moment," Spiegelman mused in conversation with Mitchell: "Then I realized that was the most pernicious thing I ever heard. It is an interesting thing, and it certainly gives license to allow one to doodle and to make whatever is in one's head visible. But it can also be a dangerous thing to shrug it off with an 'only.'"21 Spiegelman's lines, then, are never "only" lines; they are always "turning into something," always becoming-other and becoming-more in a co-articulative game of reading.

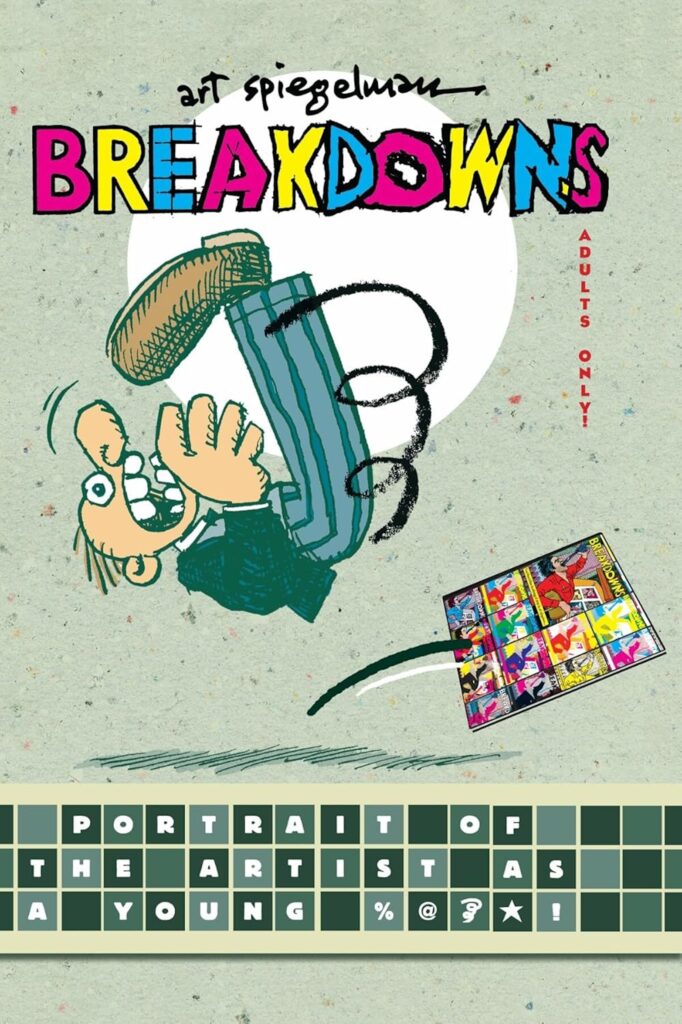

Although Spiegelman draws stylized coils of smoke in Maus, and although the Nazi swastika ("solar wheel") is itself a rectilinear appropriation of the spiral form, I want to begin this story of Spiegelman's spiral line with 2008's Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!, where the image receives its richest treatment. This sumptuously designed, large-format book is in fact two books in one binding. The first book is a facsimile of Spiegelman's hard-to-find, long-out-of-print 1978 collection Breakdowns, comprised of short autobiographical and structurally experimental comics. The second book is Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!, an autobiographical graphic novella-cum-manifesto that calls itself an "introduction" but is nearly as long and labor-intensive as the material it "introduces." Portrait deploys a series of same-size boxes that repeat and reshuffle as the sequence unfolds: memories, vignettes, and ideas interweave and overlap to mimic "the non-chronological way the mind works."22

The figure of the spiral line first appears on the book's front cover. It appears twice, actually. In one usage, it's the third character in the string of symbols that replace the last "word" of the title. As a censored profanity, the spiral glances at the comics-specific history of symbol swearing, which dates back to the Katzenjammer Kids at the turn of the century. But the spiral is also a pictorial rune in the center of the cover image, where its texture sets it apart: it has the uneven graininess of pencil or crayon, and it is reproduced in pure black, so that it stands out against the cover's blue-tone imagery — asserting itself as a drawn line, a handmade mark, if also one that has been mechanically reproduced.

The accompanying image depicts the artist, dressed as a vaudeville comedian, tripping and falling. He has stumbled upon/over a copy of his own Breakdowns book, in a self-reflexive commentary on the retrospective we are about to open. Paired with the image of the tripping cartoonist, the spiral now forks in usage again. On one hand, it serves as a "motion line," marking the path his body takes as it falls.23 On the other hand, it can be read as an "emanata," a term coined by Beetle Bailey cartoonist Mort Walker to designate the symbolic icons that "emanate" from cartoon characters or objects — sweat droplets, stars, odor lines, and so on — to denote states of thinking, feeling, and being. In his tongue-in-cheek encyclopedia of comics terms, The Lexicon of Comicana (1980), Walker defines a coiled spiral as a "spurl," which represents drunkenness and confusion (as when it hovers above Captain Haddock in Hergé's Tintin.)24

We haven't even cracked the spine of the book, and already the protean spiral has wriggled out from whatever definitive denotation we might want to grasp it with. To review: (censored) word and image, motion and emotion, authentic mark and mechanical reproduction. Within the text, the same spiral line signifies, by turns: a sudden fall, a child's doodle, a child's doodle inside the artist's head, a circuit failure, a speaking abstraction, and a form-principle of composition. This coy figure seems to graze the double limit of what is permissible and what is possible to put into words. Pantheon, in its official press releases, replaces the handmade spiral line with an ampersand, and I follow suit in typing out the title here. As a continuous, curving line that intersects itself, the "&" offers a visual similitude. The Library of Congress takes a different tack, spelling out the hand-drawn squiggle in square brackets, [squiggle]. The word "squiggle" seems to press up against the limits of language too, pushing symbolization towards imitation, mimesis, dumb repetition: a word of probable imitative origin, "squiggle" hybridizes two other words, "wriggle" and "squirm." The verbal descriptor attempts to capture the slippery, restless, iterative movement the line expresses with simple grace. The very resistance of the cartoonist's mark to translation makes it an emblem of what is irreducibly comics, demonstrating what can happen in "comics speak" that cannot happen in any other medium of discourse.25

The word "breakdowns" itself presents a tightly wound coil of complex contraries, playing on a form/content dualism that swiftly breaks down. Beyond the familiar psychological sense of the word — emotional breakdown, mental collapse — "breakdown" is also the term in cartooning for a preliminary thumbnail sketch indicating what boxes or panels make up the page. In this guise, "breakdowns" underlines the forming or building process of making comics, the work of creation, as well as the completed page as a spatial whole. The pun of the title —psychological destruction versus aesthetic construction — thus superimposes two aims: the psychological/personal/emotional and the formal (yet not, never, "merely").26 The early autobiographical work in Breakdowns homes in on Spiegelman's traumatized family —Spiegelman was in fact institutionalized for a mental breakdown in the months before his mother's suicide. The structurally experimental work, on the other hand, investigates the materiality of the comics medium: its conventions, its techniques, its vocabulary.

Yet the mental breakdown/formal structure duo is also crossed by another duo, in which the formal structure is in fact causing the reader's eyeball to stutter and break down: "It's about breaking down your attention," Spiegelman has explained.27 This attentional "breakdown" can itself be read two ways, as overworking to the point of failure and collapse, like a car's engine (intransitive), and as taking apart in order to be reassembled again or differently (transitive). Where Maus strove to be as narratively fluid as possible, Breakdowns forces the reader to slow down and reread, to stop and get her bearings, to puzzle over the interrelationship of parts, perhaps to spiral off in different directions, following a nonlinear train of thought. In this guise, the spiral line announces the work as a "vortex," a sort of attentional black hole that sucks in the reader, catching her up in a mental, interpretative spiral of dialectical visions and re-visions that resist the timeclock of facile consumption.

Evoking the recurrent motif of the stumbling artist on the cover of Portrait, Spiegelman observes of the Breakdowns pages: "[they] were made to be stumbled over, send you back to the beginning, to read and study, in other words, the opposite of short attention span."28 It is in this sense that the image of the retrospective artist spiraling to the ground finally educates us in how to read (or rather, re-read) Spiegelman, how to engage with his work in/on his own terms.29 Maus, as the artist has so often claimed, was made to fulfill the vision of "a long comic book that needs a bookmark and asks to be re-read."30 A text built for re-reading was Spiegelman's functional description of his genre/medium before "graphic novel" took hold as a punchier phrase. For all its anti-narrative experiment, then, Breakdowns is not the opposite of Maus, but rather its obverse: "It was the same instruction kit," Spiegelman explained, comparing making comics to putting together a Tinkertoy set, "just putting it from Z to A rather than A to Z or whatever."31

Spiegelman's sense of textual re-encounter finds an echo in Roland Barthes's paradoxical claim that "those who fail to reread are condemned to read the same story everywhere."32 Rereading, Barthes implies, saves one from the endless and unconscious repetitions of the repressed. And only by re-reading, Barthes continues, does one allow for play, "which is the return of the different," through which one finds "not the real text but a plural text: the same and the new."33 Spiegelman undoubtedly shares Barthes' belief in rereading as "an operation contrary to the commercial and ideological habits of our society, which would have us 'throw away' the story once it has been consumed, so that we can then move on to another story, buy another book."34 Spiegelman's emphasis on "re-reading," and on reading as play, stresses active engagement with the capacity for surprise and for convulsion, rather than passive and commodified consumption.35 As an impassioned advocate for comics (as) literacy, Spiegelman defamiliarizes reading and writing along the lines of Lewis Carroll's Mock Turtle referenced in the epigraph above, who is schooled in "Reeling and Writhing."

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Modernist %@&*!

Marking his distance from the contentedly "non-art" world of underground comix, 1978's Breakdowns asserted Spiegelman's aspirations to capital-M Modernism. An early review in Alternative Media, wonderfully titled "James Joyce, Picasso, Stravinsky and Spiegelman: A Portrait of the Cartoonist," applauds Spiegelman's high art ambitions, apparently unbothered by the history of comics as low culture, and still less by its violation of the visual-verbal, poetry-painting cross-contamination taboo. "Without relinquishing the native virtue and idiom of the comic strip, its wit and realism," reads the review, "Spiegelman has treated the popular art form as a 'serious' one and belatedly ushered it into ... modernism."36 "He was on fire," Spiegelman writes in Portrait's Afterword, poking gentle fun at his younger self:

alienated and ignored, but arrogantly certain that his book would be a central artifact in the history of Modernism. Disinterest on the part of most readers and other cartoonists only convinced him he was onto something new in the world. In an underground comix scene that prided itself on breaking taboos, he was breaking the one taboo left standing: he dared to call himself an artist and call his medium an art form.37

So what makes Breakdowns "modernist"? First, there is something to be said for the high seriousness and ambition involved in putting out a "best-of" album before one has a minyan of readers. The volume came about through Spiegelman's belief that, as Lee Konstantinou and Georgiana Banita put it, "comics could profit from reprints, reinterpretations, contextual framing, and the painstaking archeology previously restricted to the elite benchmarks of high art. Like modernist arts and writing, Spiegelman's comics work was an endlessly unfolding text whose laborious weaving and unmaking deserved intense examination."38 As a self-curated collection of previously printed strips, Breakdowns suggested that "a cartoonist could salvage as much valuable detritus as the best Joycean Scribbledehobble notebook."39 Relatedly, as J. Hoberman reminds us, "in the high modernist tradition of Joyce, Pound, and Eliot, Spiegelman has frequently been his own most eloquent explicator. The punning title of his first collection, Breakdowns, suggests a form of auto-analysis — not just personal but aesthetic as well."40

Indeed, we can recognize Spiegelman's modernism in his self-conscious investment in the materiality of his specific medium — the how of comics as a narrative procedure. As Hillary Chute argues, while Breakdowns is "littered with explicit references to Winsor McCay and George Herriman, as well as to famous exemplars of literary and visual modernism such as Stein and Picasso," the book's "attachment to, and expansion of, modernist aesthetics resides in its experiments with how to divide time and space while still remaining narrative."41 The claim for a kind of "medium specificity" in comics may seem oxymoronic, because the modernist "medium" was supposed to be pure, autonomous, held apart from both low cultural subject matter and contamination by other media forms.42 Spiegelman has no truck with this formal orthodoxy. As Lee Konstantinou has explored at some length, Spiegelman's connection to modernism inheres in his commitment to a kind of autonomy for comics: he wants to elevate his hybrid medium as its own "art form," even though, as Konstantinou also clarifies, that "autonomy" is not at all a refusal of politics.43

In Spiegelman's case, two divergent traditions of self-reference and self-reflexivity can be seen to converge. On one hand, "the self-reflexive thinking [that] had been deployed to satirical effect in Harvey Kurtzman's 1950's MAD," and which shaped Spiegelman's entire generation. This "popular, ironic, dehumanized mode reflexively concerned with the specific properties of its medium" J. Hoberman calls "vulgar modernism," a low-cultural form of modernist aesthetic production bred between 1940 and 1960 in animated cartoons, comics books, and early morning TV.44 On the other hand, an elite list of visual innovations from "German Expressionism" to "Cezanne, Cubism, and the entire convulsion that painting went through when photography threatened all of painting's previous premises."45 Notably, Spiegelman self-identifies not only with MAD, but also with the modernist dogma (and critical commonplace) of "pure form," according to which artists made paint, canvas, celluloid their subject matter.

We can bring the "modernism" of Breakdowns further into relief by placing it against a second major formal explanation or paradigm of modernist aesthetics — this one literary rather than art historical. In his landmark (if controversial) 1945 essay on spatial form in modernist literature, Joseph Frank asserted, in a now famous claim: "Joyce cannot be read — he can only be re-read."46 Based on what he observed as the halting of narrative and syntactical flow in the work of T.S. Eliot and James Joyce, Frank theorized a new "spatial form in modern literature." Meaning is not the product of graduated adjustments from chapter to chapter, but an emergent quality of the whole — and that "whole" becomes available only through reencounter.47 Frank did not consider the lowly comic-book a legitimate object of literary study, of course. Yet one can wonder: what might he have thought of the contemporary graphic novel, with its fundamental translation of time into space, its ready invitation to re-reading? In comics, "spatial form" is not, as in Frank, just a pregnant metaphor for the pattern of cross-references born of simultaneities discovered within the reading process. The reader is constantly shuttling between the "causal-chronological" flow of panels and the simultaneous coexistence of these same panels in stillness.

Scott McCloud's influential definition of comics as "juxtaposed images in sequence" highlights the sequential — and thus linguistic — dimensions of comics, as opposed to the simultaneous whole: other accounts, such as Thierry Groensteen's "arthrology," come closer to Frank's sense of spatial form as crystalline, synchronic structure. It is possible for the reader at any time to halt the time-flow of the narrative (as opposed to, say, film). Throughout the time-act of reading — that hourglass is always flowing — one can attend to the interrelationships between units of meaning. The full significance of any given panel in a comics narrative is in fact given by these relationships: between words and images, panels and page, which are juxtaposed independently of the progress of the narrative; a second-order apprehension of meaning results from the way the individual fragments speak to one another across the spatial whole (as a recurrent image returns, for example, forging a link between temporally distant moments in the narrative flow).48

But Frank's account of modernist spatial form can only take us so far. As scholars such as Brian Glavey, Rebecca Beasley, and Cara Lewis have shown, the spatial-form thesis has tended to side with a New Critical "desire to endow literature with the spatiality of an art object ... as an attempt to preserve text from context."49 Frank invokes spatiality as a way of freezing and containing the artwork, not unlike Cleanth Brooks's The Well Wrought Urn. Once again the instability or multistability of the spiral — this time, as a structural principle — provides a way forward. If Spiegelman's early comics produce a centripetal effect that consolidates artist and reader into positions of mastery over a spatialized whole, which is the psychological value of spatial form according to Frank, they also exert a centrifugal force that pulls with insistence against the enthrallment to totalizing and closural form. If, in other words, Spiegelman has a high modernist "rage for order" as Wallace Stevens might say, he also harbors deep suspicions about over-systemization — suspicions no doubt nourished by the disastrous systemization of the Third Reich. In MetaMaus, for example, Spiegelman jokingly refers to himself as "a kind of structuralist who keeps losing his moorings," an artist who gives himself a set of rules mostly so that he can break them.50 The open form of the spiral squiggle points, in its way, to Jean-Luc Nancy's polysemous definition of drawing as "the opening of form."51

I now want to situate the spiral image within a longer, larger history of twentieth-century literature and visual art. By limiting my discussion to the twentieth century, I do not at all mean to suggest that spirals appeared in the twentieth century for the first time, ab novo, nor that they dropped out of the picture in the twenty-first. Mitchell's "Metamorphoses of the Vortex," quoted above, offers a fascinating "whirlwind tour" of the form through the nineteenth century. Yet even Mitchell's view could have been much longer. My goal in focusing on the spirals of James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, and Paul Klee is to follow up Spiegelman's own self-identification as a modernist, testing that affiliation against the rhetorics of postmodernism that swirl around Maus. As I contend, reading/reeling the spiral across these visual and verbal texts allows us to "swerve around" familiar binaries of word/image, high/low, abstract/figurative, turning up new genealogies and aesthetic kinships at every turn.52

A graphic novel Künstlerroman (story of aesthetic development) chronicling how the cartoonist became the cartoonist, Spiegelman's Portrait borrows more than just its name from Joyce's Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916). Spiegelman has claimed that he once aspired to be like Joyce, because "Joyce had three or four different incarnations of himself, each represented by works that were stylistically, thematically vaguely related to each other, but were almost the works of different creatures."53 The expansive panoply of ideas and styles in the original Breakdowns anthology confirms Spiegelman's self-identification with this model — the archetype of an omnidirectional creativity impossible to squeeze into tiny boxes. Maus was supposed to be only the first of many projects, many different incarnations of the cartoonist himself. Spiegelman originally planned to arrange his father's testimony "in a more Joycean way," as he told Joshua Brown, probably referring to the Joyce of Ulysses: "Then I realized that, ultimately, that was a literary fabrication just as much as using a more nineteenth-century approach to telling a story, and that it would actually get more in the way of getting things across than a more linear approach."54

Spiegelman's Portrait reflects back on his early ambitions as a Joycean modernist. "%@&*!" — the breakdown or disintegration of language into (the representation of) cursing — allows Spiegelman to circumvent any definitive answer as to "what" the artist is. The true or core or essential self gets to remain hidden, as if in a game of hide-and-seek with the reader. Then again, perhaps the explosion of visual icons is itself an extension of Joyce — of his colorful coinages, his obscenities, even his embrace of the iconic dimensions of language. According to Anthony Burgess, Joyce "sees as a valid literary technique the forcing of words — whether as phonetic or orthographic structures — into a semiotic function which shall be iconic more than conventional."55 Frederic Jameson, noting that "one of the classic definitions of modernism is of course the increasing sense of the materiality of the medium itself," asserts that Joyce's emphasis on the materiality of the medium of language relates to the emphasis on the materiality of the medium in plastic arts such as painting.56 Spiegelman's transmediation of Joyce into grawlixes ironically points up a deeper affinity between the modernist author and the cartoonist, underscoring the "comic" and even graphical dimensions within Joyce's own production.

When, in 1929, Harry and Caresse Crosby of the Black Sun Press in Paris decided to publish three fragments from James Joyce's Work in Progress (the beginnings of Finnegan's Wake), they wanted a portrait of the artist, preferably by Picasso, to be the frontispiece. Picasso refused the commission, so they recruited Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi. Brancusi set to work: first, he drew a deft image of Joyce with round spectacles (it was rejected as insufficiently avant-garde); next, he produced a family of abstract drawings featuring spiral lines, undulating with the turns of the pencil or brush, shown from the side, above, and in cross-section. In the final Symbol of Joyce (1929), a logarithmic spiral turns hypnotically around our perpendicular axis of vision. Although Brancusi rarely made sculptures from his drawings, he also translated his Symbol into a sculpture by placing a spiral of wire in a shallow cone of paper.57 In 1954, Brancusi told Joyce's biographer, Richard Ellman, that the spiral captured the sense of pushing, urging, driving (sens du pousser) he associated with the writer. Some critics understand the spiral as an ear; others, a symbol for the thick lens that Joyce had to wear over his near-blind left eye.58 (Spiegelman is also nearly blind in his left eye.) Joyce himself saw only a "wrecked" face, a "whirligag," as he put it in a letter to a friend.59 For our purposes, we can say that the spiral as ear and lens undoes the distance between the aural and optical channels: language and art, respectively. Spiegelman's spiral line inscribes this Joyce at the origins of his own aesthetic bildung.

But if Spiegelman's spiral motif — if the matrix of associations within which the spiral mark is embedded — reveals an affiliation with Joyce, the image further illuminates an intertextuality with Samuel Beckett. In Beckett, one finds a modernist giant who, like Spiegelman, suffered a severe nervous breakdown, and one whose oeuvre also revolves questions of time, memory, and the self from an absurdist stance. Reading Beckett with Spiegelman under the sign of the spiral elucidates a motif central to Spiegelman's Portrait: the artist as circus clown or music-hall comic, pratfalling over a banana peel, with the spiral line emanating alongside. Spiegelman links the conceit explicitly to Beckett, as we see in his "Meet the Author" feature for BookPage. There, the cartoonist redraws his stumble, adding Beckett's quote as a caption: "Try again. Fail again. Fail better." In a three-panel mini comic, we see a cute little baby Spiegelman, flapping his hands, gurgling "Try again!"; to the right, Spiegelman's adult self stumbles and falls over his ever-present banana peel: "Fail again!"; the punchline comes from a skull-and-crossbones beside a headstone: "Fail better." Death represents the paradox of the "best" or consummate failure: failure not redeemed but rather perfected. Life is an absurd series of pratfalls unto the grave.

Spiegelman recruits Beckett to send up (and send flying) the pretensions of his own "retrospective" double-act. The old banana-peel-fall-stunt is as cheap and predictable as it gets. It stands for everything the ambitious young artist did not want to be as a cartoonist: a vendor of vaudeville-style diversions. But it also parodies the "performance" or "routine" of autobiographical retrospect and self-archivism, as enacted both by the 1978 Spiegelman and, again, by the 2008 Spiegelman. Thus the exaggerated gesture of the artist falling over his banana exaggerates the gesture of the young artist guzzling a jar of ink on the original Breakdowns cover: wild-eyed, open-mouthed, thrown back off balance. Past and present form a straight-man/funny-man double-act. The earnest, ambitious young artist provides the serious, known quantity for the funny man to play off in a restaging of the life-as-gag.

Where Joyce and Beckett rely on words to conjure the image of the spiral, Spiegelman can deploy the resources of the graphic arts. In comics, the drawn line itself can spiral. Mitchell, in his Afterword to the Critical Inquiry special issue, "Comics & Media," speaks to this graphical tradition of spiral lines when he designates the spiral line or vortex "the signature of the artist since Apelles and Hogarth, the sign of transformation and empathetic doodling."60 In the interests of filling in some of the many names that come to mind between Hogarth and Spiegelman, I want to briefly turn to Paul Klee — a figure to whom Spiegelman alludes often in his sketchbooks. Klee, who deploys the spiral often in his paintings and drawings, theorized its form as the purest form of motion. In his Pedagogical Sketchbook, he describes the movement of the spiral in life-or-death terms:

We need to know the direction of motion, because the question depending on increase or retraction of the radius has psychological relevance. The question is: do I get released from the center in more and more liberated motion? Or do my motions get increasingly bound by a center, until it finally devours me completely? - This question means nothing less than life or death.61

It is in the context of the spiral's dynamic motion that Klee formulated his dictum: "Good is formation. Bad is form. Form is the end, death. Formation is motion, is action. Formation is life."62 Most apposite for a study of Spiegelman is the way Klee makes the movement of the spiral a problem of and for psychology. In Portrait, to "spiral" is to fall into the vortex of memory, the all-devouring "Memory Hole" (drawn as a noir urban labyrinth in which Spiegelman gets lost, trailed by his detective character). And, as I develop in the next section, the trauma of Spiegelman's absent mother lies at its center.

Breakdown: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Scribbler

If Maus is primarily the story of the father, and of the father-son relationship, Portrait pivots its gaze to Spiegelman's mother. This is not entirely surprising: Portrait claims to re-introduce Breakdowns, which includes "Prisoner on the Hell Planet" (1972), Spiegelman's wrenching account of his mother's suicide and its effect on him, rendered in a German Expressionist style that owes much to the wordless woodcut novels of Lynd Ward. (Readers of Maus will also recognize the comic, which appears in smaller-scale reproduction within the pages of Spiegelman's first volume.) Yet, Portrait accords deep importance both to "Prisoner" and to Spiegelman's mother, Anja, herself, who floats in and out of these story fragments as a diegetic character and persistent influence. A compelling body of scholarship already exists about the traumatic absence of the mother from Maus, and I will not review it here.63 May it suffice to quote from MetaMaus, in which Spiegelman claims that his mother's first-person survival story is "arguably the one I would have told if all else were equal in an alternate universe."64 I have suggested that Spiegelman's pratfalling vaudeville clown bears closer inspection: his striped pants resemble the Holocaust pajamas Spiegelman's autobiographical character wears in "Prisoner." In what follows, I "break down" (analytically) two critical pages from Portrait — the first and the last — to show how Spiegelman's modernist formalism spirals out towards the mother.

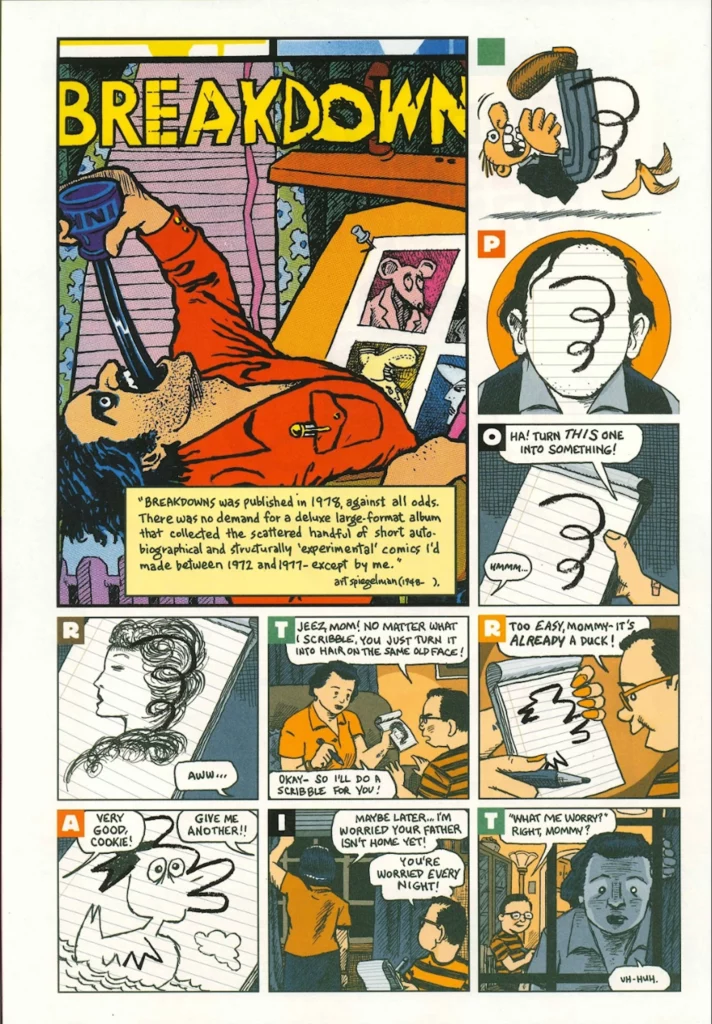

The trauma of losing Mom gathers in the shadows around Portrait's opening sequence. Each square panel of the strip unfolding from and around the Breakdowns cover image bears a colored letter label in the corner, based on the grid of colored squares spelling out the title of the series, "Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!" on the title page. Each word is separated by a blank or "spacer." A blank green tile labels the first (unbordered) frame. A red tile with the letter "P" labels the frame immediately below this one, and so on. Together, they spell out the titular word "P-O-R-T-R-A-I-T." The little colored tiles evoke a child's alphabet tiles or a reading primer: the page performs an orthographic "breakdown," an object lesson in how to read Spiegelman, how to "break down" his breakdown, in the psychological and compositional senses of the word. A short autobiographical vignette, a narrative "portrait of the artist," gradually takes shape around the repeating image of a spiral squiggle, which stamps itself down the center of the first four panel frames. It's a sort of palinopsia or recurrent afterimage: usually, pictures play against a fixed background; here, the spiral is fixed while the scenery morphs around it. The abrupt, "non sequitur" transitions between these initiating panels are cognitively disruptive; one has to sound out the emerging "story" — and sound the depths of Spiegelman's memory — as one literally sounds out the title.

In the panel labeled "P," a portrait of the adult artist appears, wearing his collared shirt and his signature black vest; his face has been replaced by a sheet of ruled notebook paper with that indelible spiral in the center. This image (notebook with squiggle) will congeal into a followable story in the next frame, but for now it's "only" a line in the artist's head, a mark on paper: nonfigurative, unfigurable. Perhaps it suggests the birth of a comic, before the artist has translated whatever is inside his head to the page. Perhaps it is a representation of a memory trace, almost as if the notebook were Freud's Mystic Writing Pad.65 If we read backwards, allowing the abstract "P" panel to frame the vignette that follows as a sort of paratextual header, we can say that this spiral line is the residue of former spaces, a sort of graphic remainder left over from story fragment it (literally) "heads off." Spiegelman depicts his face both as a surface for writing and as the surface for memory's inscription. The cartoonist's identity and name collapses into the "medium of the mark," in the phrase of Walter Benjamin. What is frightening in this sequence is how memory's inscription "obliterates" Spiegelman's featured face (the verb means to graphically strike out). The figural troping of the artist's face de-faces him in an uncanny literalization of Paul de Man's famous thesis, "Autobiography as De-facement."66

These complicated dynamics of figuration and effacement inform the vignette that takes off in the next panel. In the panel [O], we see once more the spiral and the notebook paper, only this time, the lined paper is attached to a pad, held in a child's hand (with a little Band-Aid at the wrist). A speech bubble appears: the child is speaking to someone (to whom? to us?), laughing with pleasure: "Ha! Turn THIS one into something!" Another speech bubble ("Hmmm...") positions the object of this address just over our shoulder. The emphatic "this" refers, it seems, to the spiral itself. This panel presents an invitation to make meaning of this line. Gotcha. Tag you're it! Collaborative meaning-making as Wittgensteinian language game.

The page unfolds a play scene between mother and son. Reading across the next row, young Art and his mother play a popular drawing game on a blank, blue-ruled notepad, taking turns making doodle pictures out of each other's abstract lines. Art makes the spiral squiggle and hands it to Anja to turn into a representational picture. She compulsively draws, much to Art's dismay, another iteration of "hair on the same old face" she always draws — the profile of a thin-lipped woman with closed eyes. Anja's unconscious avatar takes shape as a woman who does not (cannot?) return her son's look: and a woman with hair. One also detects a resemblance to the blue Picasso woman on the drawing board in the 1978 cover image. Anja, like all the women in Auschwitz, was shaved bald. According to Spiegelman, Anja was ashamed to have her husband Vladek see her. Anja's drawing repetitiously tries to cover her past, her shame.

In her turn, Anja makes a scribble for Art. It is random, jaggy, very unlike the smooth and composed spiral by her son. Art draws an adorable cartoon duck in a sailor's cap. But Anja is too worried to play further because her husband isn't home yet. The mother-child idyll breaks down as the absorptive moment is ruptured by the mother's creative inhibitions, by the symbolic intrusion of the father, by Anja's own war-haunted past. Here the emotional subtexts shaping the mother-child encounter gain graphic form through their shared production of lines on paper.

In the strip's offbeat punchline, Art proudly trots out the slogan of his beloved MAD comic books, "What, Me Worry? Right, Mommy?" while Anja peers out of the window, distracted: "Uh-Huh." This exchange puts words to what we have already read "between the lines" of the drawing pad: Anja's inability to stay present for her son in the way that he seems to want. At the close of the scene, the relationship between father and son leaps onto the page. In a transparent Oedipal configuration, the father is coming home to interrupt the connection between mother and son. Anja declines her turn: "Maybe later ... I'm worried your father isn't home yet!" she says. This scribble game is played in the father's absence: there is perhaps the sense that it would not be possible in his presence; the father threatens the mother-son play. Zooming away from the drawing pad in close view, we see mother and son on opposite sides of the picture. Anja has pulled up the blind to look out a many-paneled window. Artie's protesting sulk — "You're worried every night!" — sets up the strip's punchline in the following frame. Here, the son's sensitivity to the mother's worry cues the descent of "real Madness" over the Spiegelman household, foreshadowing Anja's suicide.

The final "T" panel lands us at the bottom of the page, as if outside the childhood home, looking in from without. In the episode, Anja's face is framed in the window/panel: Artie solicits her attention while she turns away, unlike how she solicits his (grudging) attention in "Prisoner on the Hell Planet" on the night before her suicide. There, she comes to her son's room at night with a plea for love: Art grunts "Sure, Ma!" and turns away. Here, Anja's spiritless "Uh-huh" echoes the prisoner's noncommittal shrug-off. Indeed, the blue-toned close-up of the mother's face offers a visual analogue to the portrait of the artist ("A" for "Artist") initiating a sequence about the creation of "Prisoner on the Hell Planet." Instead of a face, the prisoner-artist has a blank surface inscribed with the letters "Hell Planet." Each "Portrait" strip begins a portrait cameo of one "face" of the artist, rendered in a different graphic style, which together produce a constantly shifting, kaleidoscopic psychological portrait of the artist in the self-interpretative act — attempting (according to the noir-style voiceover of his midget detective character, Ace Hole) "to locate the traumas that shaped and misshaped him." 67The scribble Spiegelman's child self makes for the mother to complete gives him his identity as a cartoonist — the cartoonist who is constantly slipping over his own history — even as it destroys his recognizable features.

This encounter between the young artist and his mother also stages a — suggestively missed — encounter between psychoanalytic theory and the comics. Donald Winnicott adapted the same popular drawing game into a psychotherapeutic technique for use in initial consultations with his child patients. This game would later be regarded as Winnicott's "most famous technical invention," although the analyst referred to it much more simply as a game he "liked to play with no rules," or "the Squiggle Game."68 Something of the unruly, agitated, childlike energy of both wriggling and squirming — as of a child who refuses to remain still — animates Winnicott's technique. It is a technique that crucially disrupts the clinical hierarchy between doctor and patient: it blends talking and drawing, word and image, to create a shared space for transformation and surprise. The analyst scrawls a rudimentary line on a piece of paper and then hands it over to the young patient, saying: "You show me if that looks like anything to you or if you can make it into anything, and afterwards you do the same for me and I will see if I can make something of yours."69 As Winnicott summarized the effects of the game: "often in an hour we have done twenty to thirty drawings together, and gradually the significance of these composite drawings has become deeper and deeper, and is felt by the child to be part of communication of significance."70

The symbolic space conceptualized by Winnicott materializes in Spiegelman as the blank page of the notepad upon which is inscribed a line that is the precipitate of an intricate interweaving of temporalities: the child's first scribble, recast by the mature artist as a symbolic shorthand, if not a signature. The "P-O-R-T-R-A-I-T" sequence on the first page becomes a kind of "Squiggle Game" the adult artist plays with and by himself, yet which casts the reader in the maternal — and by extension, psychotherapeutic — position. The "active" reader recruited by the participatory comics form turns rough marks into story, dream-residue into meaningful presence. The space of the drawing pad, and the realm of the visual more broadly, is proposed as a powerful, even compulsory site of memory and history-construction — memory and history-construction as moreover collaborative, interlocutionary activities — where the past is preserved but also transformed. The artist's drawing pad offers up a leaden signifier of the past, the unexpurgated spiral, a remnant of former marks and spaces, a lingering gesture (like a motion line etched in the air), for transformation: "Ha! Turn THIS one into something!" says the young "%@&*!" to his mother and his adult self alike.

At the risk of a caricatural reduction of this page's complexity, one might conclude that the "breakdown" (stuttering, stopping, coming apart) of the scene of mother-son play turns Spiegelman into the cartoonist he became. Along these lines, the psychological/emotional/mental breakdown implied by the wild-eyed artist poisoning himself with a jar of ink seems to undergird and touch off the composition of the portrait (if not also of the original Breakdowns work). Here, the personal/autobiographical "breakdown" provides the conditions of possibility of its aesthetic counterpart. If swilling a jar of ink communicates psychological distress, it also and allegorically figures the printing process by which the paper is said to "imbibe" the ink (that is, allow it sink into the surface.) One might even view the image as a reverse exsanguination of ink, with ink as blood. Spiegelman's trauma "feeds" his production, as ink is "fed" into a pen. Spiegelman turns his body into a pen. At the very back of the Breakdowns anthology, on the last page of "Ace Hole," Spiegelman has placed a parody newspaper column of advertisement listings and get-rich-quick scams: "Be A Detective!" "Draw for Money: Be an Artist!".71 Sandwiched between two ads is a quote from Picasso that resonates with the image of the front book cover, repositioning the poisonous ink as a point of aesthetic departure as good as any other: "Everything is a starting point. One swallows something, is poisoned by it, and eliminates the toxic."

Breakdown: Portrait of the Artist as a Young Scribbler Formalist

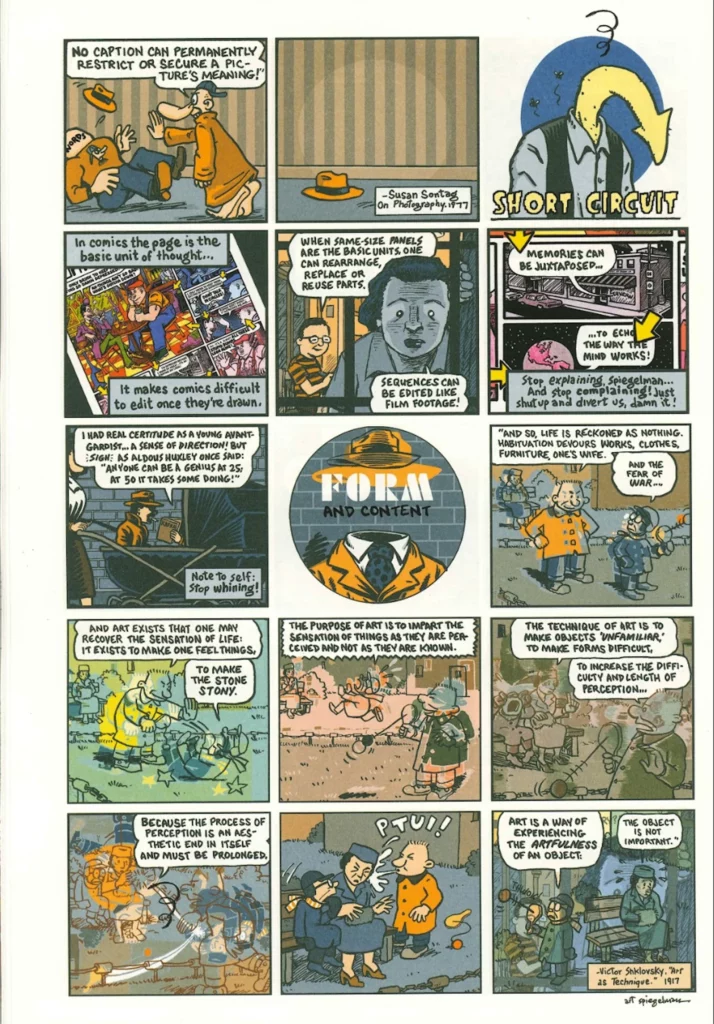

On the last page of Portrait, the spiral returns as both an image in the text and a second-order pattern, a structural image of the text. Motif shape and chromatic pattern inscribe, in a kind of visual shorthand, relationships between panels or scenes down the page. One notices how the gesture of "Pictures" knocking over "Words" (top left) is mirrored in the gesture of the bully knocking over Art (fourth tier, far left.) The orange hat that "Pictures" knocks off "Words" in the vaudeville show of "Words" and "Pictures" is picked up by the circular panel in the center of the page: a portrait cameo of the artist as an invisible Ace Hole, with the words "Form and Content" written across the empty space of his face. The hat that had belonged to "Words" now levitates above the empty suit, even hovering outside its outline, much as "Form," in bold stencil white letters, seems to float free of the black linear "Content." From there, the orange suit jumps to the figure of the bully who insults Art and Anja across the latter half of the page. The stage routine of "Words" and "Pictures" is more than erudite hijinks and the impersonal question of "Form" and "Content" is not, in fact, divorced from autobiographical experience. The formal battles/playgrounds are linked, however subliminally, to the deepest conflicts and games of memory.

Erin McGlothlin reads Spiegelman's spiral as a symbol for autobiographical performance: "By visually foregrounding the act of looping," she writes, "the squiggle concretizes ... the trajectory of his method of autobiographical re-vision, which, like the looping squiggle, performatively returns again and again to the same life moments," recasting them each time anew.72 Thus, the closed circle of the memoir opens instead into a self-reflexive spiral. The return is not a true return, not a regressive collapsing back on the past, but rather a re-constellation of the familiar in a novel form. This is the dynamic aspect of McGlothlin's "backhanded squiggle," which returns to its origins displaced along the axis of motion. The returning material is new and strange, rearranged in a form of free-associative montage: cut, spliced, layered, equalized, and "overdubbed" with Spiegelman's meta-narration about the structure and psychology of comics form.73 Here, the stuff of personal history is subsumed into a universalizing discourse about the medium, about what happens, psychologically, when anybody reads comics. The series' oversize pages have become a shared past, endlessly returning in new combinatorial permutation. With each return, new associations emerge.

In the short sequence that begins at the end of the top tier, "Short Circuit," Spiegelman directly, even didactically refocuses our attention on the second-order unity of the page:

In comics the page is the basic unit of thought...It makes comics difficult to edit once they're drawn. When same-size panels are the basic units, one can rearrange, replace or reuse parts. Sequences can be edited like film footage! Memories can be juxtaposed...to echo the way the mind works!74

With same-size panel squares as "the basic unit," as elemental syntagm, Spiegelman "samples" freely from earlier in the series and from the Breakdowns strips. While the strip's visuals cut and splice together disparate panels/moments from across Spiegelman's life and oeuvre, the text in the text boxes and speech balloons has been replaced by Spiegelman's meta-narration about manipulating comics "footage." Spiegelman exploits the comics' aptitude for showing and telling at once, with the text describing what the sequence performs as it is performing it. This performance of repetitions-with-a-difference conveys memory as a process of retrieval and concomitant reinvention. The memory trace becomes, like the child's mark, like the spiral squiggle on the notepad, a residue to create with.

The title, "Short Circuit," references the dense, multi-narrative 1975 Breakdowns page, "A Day at the Circuits," in which the page is emphatically the basic unit of thought. "Five or six comics on one piece of paper," Spiegelman has commented about the economies of this page: [I am] my father's son."75 A scaled-down image of "A Day" appears cropped and at a tilt (second tier, far left), where it is marshalled as an object lesson in the extraordinary intricacies of page construction. In the 1975 page, a selective use of color families (blue and magenta) and little yellow arrows, as in a circuit diagram, lead the reader around according to various narrative pathways. Each of the narratives coiled into this page represent an expansion, contraction, or variant of a drunk's logically circular quandary: "I only drink to keep from getting so damn depressed!"; "I'm depressed because I drink so much!" The "shortest" narrative circuit, represented by a single panel subdivided into two elongated rectangles, involves the drunk's drinking buddy suggesting his friend slash his wrists to get out of his dilemma (as Spiegelman's mother herself did). "Dead end. Start again." Themes of alcoholism and depression are treated with self-conscious irony and wit, as when a series of prescriptive yellow arrows figure the deterministic fatalism of depressive thinking so that a vicious circle of destructive behavior becomes a literal circuit.

In "Short Circuit," Spiegelman plays off the formal experiment of "A Day at the Circuits," returning to excavate latent personal meaning in the original strip. In this triptych, we notice how the orange-shirted drinking buddy in "A Day" precisely mirrors the figure of little Artie in the adjacent panel, squiggling on his notepad. The conversation between the depressed figure and his buddy in "A Day" can be read as a displacement or sublimation of the feelings aroused by Artie's relationship to his deeply depressed mother, whose blue, shadowed, haunted face appears in the middle of the strip, as though trapped behind bars rather than window panes. And then, the mother's form (blue-tone, collared shirt) precisely mirrors that of the adult artist Spiegelman in the introductory panel: the artist who is all bent out of shape. Spiegelman wears his Maus uniform (collared shirt and vest) and his head is a scuzzy yellow arrow, with old age marks and protrusions of little hairs, which droops sadly from his shirt collar like a flaccid penis. Flies buzz around his shoulders, as around a dead thing. The spiral squiggle appears above him, like the wind-whipping banner of a downturn, failure, dysfunction.

The juxtapositions of this sequence link Spiegelman's psychological distress back to the mother. The sons channel his mother's depression and short-circuits. The metaphor of the shorted circuit in this strip itself evokes the powerful close of "Prisoner on the Hell Planet," in which Artie in his prison block accuses his mother of committing the perfect crime: "You put me here ... shorted all my circuits ... cut my nerve endings ... and crossed my wires!..."76 In "Short Circuit," Spiegelman makes explicit how both he and his mother relate to the "Dead End. Start Again" pathway from "A Day at the Circuits." A little yellow arrow directs us from the shadowed image of Anja's worried face to the final frame in the "A Day" sequence, showing a little planet earth (or is it the Hell Planet?) in a pan out to outer space. The tall window panels framing Anja's face appear as if 90-degree rotations of the horizontal panels within the "A Day" panel. Another set of little yellow arrows (first of all the artist's surreal arrow-head) similarly direct readerly eye-flow: against the conventional Z-pattern of left-right reading, we drop straight down onto the same square.

The concluding strip in the series, "Form and Content," espouses and itself enacts Spiegelman's artistic credo, providing the art-theoretical tools necessary to locate what Spiegelman was and is doing with the tradition of avant-garde aesthetics. Flanking the image of Ace in the baby carriage, we see another circular portrait frame of the artist as a bodiless Ace Hole, Ace in a Hole, with the words "Form and Content," inscribed in the eerie air space between the hovering hat and collar (replacing the previous text, "Memory Hole").77 If "Form," conventionally understood, provides the suit or clothing for "Content," this strip proposes rather the formal wrapping without the body.

The text of the strip is a quotation from a 1917 essay by Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky, "Art as Technique":

And so, life is reckoned at nothing. Habituation devours works, clothes, furniture, one's wife. / And the fear of war... / And art exists that one may recover the sensation of life: it exists to make one feel things, / to make the stone stony. / The purpose of Art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. / The technique of art is to make objects 'unfamiliar,' to make forms difficult, / to increase the difficulty and length of perception... / because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged. / Art is a way of experiencing the artfulness of an object: / the object is not important.78

With these words, Shklovsky lays out the (Russian) Formalist credo of the purpose of art. Shushan Avagyan's recent translation is even more compelling, insofar as it underscores Shklovsky's insistence on art-as-process: "Art is a means of experiencing the making of an object; the finished object is not important in art."79 Spiegelman's quotational strategies are often ironic but not here. One need only open Spiegelman's 2007 Autophobia sketchbook for proof of the cartoonist's allergy to "Finished Art," in his phrase: "Ink and bloodstained pages, on the battlefield, left to die, abandoned after being overworked and hacked away at ... all their spontaneity beaten out of them! They're...FINISHED!"80 This sketch goes so far as to imagine "finishing" the art-object as murder, beating the life out of it.

Because perception is habituated and automatic, Shklovsky contends, the purpose of art is "ostranenie," or defamiliarization — the artistic technique of forcing the audience to see common things in an unfamiliar or strange way, to enhance perception of the familiar. Estrangement (ostranenie): "the sensation of surprise felt toward the world, a perception of the world with a strained sensitivity."81 Art is essentially revolutionary, radical, disruptive. Art breaks objects out of their habitual sequences. By roughening and retarding the smooth flow of narrative, art — as "technique" — is the tool that enables the world to be "seen," and not merely "recognized" according to pre-existing schema. For Shklovksy, an original, child-like mode of interacting with the world has been lost ("Art exists that one may recover the sensation of life..."). Formalism is, perhaps, the displacement of the desire to recover origins — the desire driving the autobiographical project — onto a desire to recover an original way of being in the world.

In "Form and Content," Spiegelman demonstrates the Formalist principles his cast of childhood characters jointly prescribe. The panels of the strip repeat, in full, a sequence from the very beginning of the series, heightening the sense of a reverse in direction, a return to beginnings. A bully steals Art's ball-toy and spits in his mother's face while Art sits with his mitten in his mouth. But, once again, all the speech bubbles have been refaced and overwritten, or, in Formalist terms, "made strange," defamiliarized. Through a bizarre act of ventriloquism, the bully, Art, Anja, and even the spiral squiggle all take turns delivering the theorist's words. The typographical "character" has become a speaking character, the figure, prosopopoetic.

On the level of the panel visuals, Spiegelman reprises the printing strategies he had used for the original Breakdowns cover: offsetting color overlays to create a double vision of form and outline, rotating and superimposing printing plates to build colorful abstractions.82 The reader is forced to slow down; Spiegelman's technique "increases the difficulty and length of perception," so that we linger over these panels, marveling at the "artfulness" of their construction, or making. In fact, by calling attention to how the panels have been put together, "Form and Content" can be seen as performing another key move of Formalist estrangement: "laying bare the device."83 Laying bare the device represents an extreme form of defamiliarization, as the very medium of sign production is foregrounded in its artificiality.

Spiegelman prioritizes the endless surprise of process over product, resisting the congealing of art into fixed rituals of perception. By reprising the visual abstractions of his original Breakdowns cover, this strip pries form from content, the "what" from the "how," and offsets them like layers of Zipatone. The pictures do not simply illustrate the words: here words and pictures antagonize each other, as perhaps foreshadowed by the earlier vaudeville scene of "Pictures" pushing thuggish "Words" to the ground. Meaning unfolds in a spiraling, dialectical movement, as one seeks some higher reconciliation for the conflict between words and pictures, form and content. "Art exists to make one feel things," says the spiral, pure line, elemental form, the doodler's spiraling thought: "Perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged." Of course, not all perception is pleasurable: by prolonging the process of retrospection, Spiegelman feels the pain of getting knocked over by a bigger boy, the shame of being called a crybaby, the powerlessness of witnessing his mother's humiliation. The key panel of the strip, a wordless frame in which the bully spits on Anja ("PTUI!"), has not been manipulated. It remains sharp, punctuated, like the plosive "PTUI" of the spit. Untransformed, impossible to transform. Artie sits scooted up by his mother's side with his mitt in his mouth, looking shocked. The child's muteness carries over to the singular silence of the panel itself, which has no speech component. It is the bully who dominates the oral/aural channel, projecting a stream of saliva directly into Anja's ear.84

What should we make, then, of the (re)turn to abstraction — visually and conceptually —at the end of the sequence? Is it about foregrounding the creative process, inviting the reader/viewer to slow down and feel? Or is it a kind of diversion, a turning away from the traumas of memory, howsoever incomplete or unsuccessful? Can it be both, as the opposed turns of the spiral? In Spiegelman's work, art is not only a way of experiencing the making of an object and the process of creativity in action; it is also a way of remembering (re-membering) lost objects. When Shklovsky speaks of the "object," he is referring to the art object, the artistic creation, not its referent. But Spiegelman's recontextualization allows other meanings to slip in through the cracks: not the material artifact that is perceived, but rather the person or thing to which an action or a feeling is directed. Beneath or alongside that impulse to prolong the process of perception we find, perhaps, the child's desire for his mother: the crying of the crybaby refined into the whining of the dissatisfied artist-genius; the cartoonist hollering outside the kingdom of Art, trying to get heard over all the noise. In her lecture on portraiture, Gertrude Stein said that "the inevitable seeming repetition in human expression is not repetition, but insistence."85 Not repetition but insistence (etymologically, "standing upon") captures the thrust of emphasis in the final panel, with its palimpsest of mother-child tableaux. The overlays here recreate the blind groping of memory itself towards its object, wavering mirage-like at the limits of recognizability. "The object is not important," Anja says feebly, surrounded by lines indicating distress and shame. And yet Spiegelman gives the maternal object the last word.

Emmy Waldman is a Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of English at Virginia Tech, having received her PhD in English from Harvard. She will begin as Tenure-Track Assistant Professor in the Department of English at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, FL in August 2026. Her first book, Filial Lines: Art Spiegelman, Alison Bechdel, and Comics Form is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press in spring/summer 2026. Her work appears or is forthcoming in Twentieth Century Literature, Contemporary Literature, New Literary History, ASAP/J, Harvard Divinity Bulletin, among others.

Banner Image by Giorgio Trovato on Unsplash

References

- Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. by Maria Jolas (Beacon Press, 1994), 215. [⤒]

- Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass (P.F. Collier & Son, 1903), 120. [⤒]

- Edward Said, "Secular Criticism," Critical Theory Since 1965, ed. Hazard Adams and Leroy Searle (Florida State University Press, 1986), 604-22. [⤒]

- According to Said, the competing personal, corporate, and collective structures of "affiliation" are based on institutional connections, conventionalized values, and the educational purpose of the avant-garde to both enlighten and control the "masses" through its media. What has tended to happen since the high modernist crisis of values is that these affiliative structures begin to coalesce to duplicate the hierarchical relations typical of the old culture of filiation. They then become as repressive as the religiously ordered, pre-modern society they stepped in to replace. [⤒]

- Said, "Secular Criticism," 616. [⤒]

- See especially Comics and Modernism: History, Form, and Culture, ed. Jonathan Najarian (University Press of Mississippi, 2024). Another important assay into the comics-modernism connection is the forthcoming Modernism/modernity cluster, "Modernism in Comics," edited by Matthew Levay. [⤒]

- Quoted in Hillary Chute, "Afterword: Graphic Modernisms," in Comics and Modernism: History, Form, and Culture, ed. Jonathan Najarian (University of Mississippi Press, 2024), 303. [⤒]

- Hillary Chute, "Afterword: Graphic Modernisms," 305. [⤒]

- Shawn Gilmore, "Modernist Disruptions: Art Spiegelman as Experimenter, Editor, and Critic," in Comics and Modernism, ed. Jonathan Najarian (University of Mississippi Press, 2024), 49. [⤒]

- Gilmore, "Modernist Disruptions," 64. [⤒]

- To my knowledge, only one scholar to date has read Maus through a modernist lens. In her fascinating essay, "Maus, Modernism, and the Mass Ornament," Georgiana Banita argues that "in verifying the book's modernist credentials and claim to fame, Maus's scores of victims and panoramic sites of disaster are at least as important as Vladek's moving testimony," (np). Banita draws attention to "mass imagery" or imagery of the masses in the memoir "to show that Spiegelman's figuration of crowds reflects the deep-seated modernist paradox pitting individual expression against mass behavior. Specifically, Spiegelman's fraught allegiance to both mass culture (the comics medium) and high modernism (through his affinity for the avant-garde) manifests itself with particular clarity in the way he represents crowds as victims, witnesses, and literary publics." Ultimately, Banita proposes that Spiegelman crafts "a particular (non-trivializing, non-infantilizing) brand of 'low modernism' that reaches a mass readership without making light of the millions who lost their lives in the Nazi death camps." "Maus, Modernism, and the Mass Ornament," Modernism/modernity Print+ 6, no. 3 (2021). [⤒]

- Linda Hutcheon, "Postmodern Provocation: History and 'Graphic' Literature," La Torre 2, no. 4-5 (1997): 308. Another version of this article was published as "Literature Meets History: Counter-Discursive 'Comix,'" in Anglia 117 (1999): 5-14. See also Eric Berlatsky, "Memory as Forgetting: The Problem of the Postmodern in Kundera's 'The Book of Laughter and Forgetting' and Spiegelman's 'Maus,'" Cultural Critique no. 55 (2003): 101-151; Rosemary Hathaway, "Reading Art Spiegelman's Maus as Postmodern Ethnography," Journal of Folklore Research 48, no. 3 (2011): 249-267. [⤒]

- Quoted in Hillary Chute, "Introduction: Maus Now," Maus Now: Selected Writing (Pantheon, 2022): xv. [⤒]

- Here I follow Hillary Chute's sense that the key difference between modernism and postmodernism, at least as it pertains to the comics medium, lies with "the refiguration of the 'popular,' a heterogeneity of aesthetic and cultural practices, what Marianne DeKoven identifies in Utopia Limited as the 'free mixing of previously distinct modes of cultural practice and form,' in which 'popular culture, vehicle and expression of postmodern egalitarianism, is no longer meaningfully distinct from either high culture or from consumer culture (17). Comics may have features of high visual and literary modernism, yet the crucial difference with comics is that it resides in the field of the popular" (358). See Hillary Chute, "The Popularity of Postmodernism," Twentieth Century Literature 57, no. 3/4 (2011): 354-363. [⤒]

- Roland Penrose, Picasso: His Life and Work (University of California Press, 1981), 14. [⤒]

- WJT Mitchell, "Metamorphoses of the Vortex: Hogarth, Blake, and Turner," in Articulate Images, ed. Richard Wendorf (University of Minnesota Press, 1983), 127. [⤒]

- see Nico Israel's fascinating study of the "whirled image" in visual artists and writers of the twentieth century, Spirals (Columbia University Press, 2015). Israel argues that this "ambivalence or bidirectionality inherent to the spiral form is crucial both for the twentieth-century visual artists and writers who embrace the spiral as fundamental to their practice and for a study that seeks to understand or take account of the art and literature involving or revolving around those spirals" (23). [⤒]

- Bachelard, Poetics of Space, 215. [⤒]

- Mitchell, "Metamorphoses of the Vortex," 130. [⤒]

- R. Crumb and Peter Poplaski, The R. Crumb Handbook (M.Q. Publications, 2005), back cover. [⤒]

- W.J.T. Mitchell and Art Spiegelman, "Public Conversation: What the %$#! Happened to Comics?," Critical Inquiry 40, no. 3 (2014): 27. [⤒]

- My reading of this text is indebted to the fascinating three-part interview between Spiegelman and Chute, printed in Print magazine. [⤒]

- On how motion lines derive their meaning, see Irmak Hacımusaoğlu and Neil Cohn, "The Meaning of Motion Lines?: A Review of Theoretical and Empirical Research on Static Depiction of Motion," Cognitive Science: A Multidisciplinary Journal 47, no. 11 (2023). [⤒]

- The "spurl" may be seen to represent the idea of a "spinning" head, or perhaps the swerves and turns of a drunk. Either way, the squiggle-as-spurl is significant for the way it makes visible an interior state. [⤒]

- See Hillary Chute, "Art Spiegelman, Part 5," PrintMag, June 15, 2008. [⤒]

- In terms that resonate with Spiegelman's structuralist experiment, Sergei Eisenstein describes the pun as a telescoped montage, an act of montage by superimposition. See Nigel Morris, "Eisenstein: Revolutionary and International Modernist," Yearbook of English Studies 50: Back to the Twenties: Modernism Then and Now, 95-115. [⤒]

- Quoted in Kenneth Barker, "Early Work of Art Spiegelman in 'Breakdowns,'" SFGate, November 1, 2008. [⤒]

- Burke, "Early Work," italics mine. [⤒]

- [⤒]

- Art Spiegelman, "CR Holiday Interview #1 — Art Spiegelman," interview by Tom Spurgeon, The Comics Reporter, December 19, 2011. [⤒]

- Art Spiegelman, "Graphic Lit: An interview with Art Spiegelman," interview by Chris Mautner, Panels and Pixels, October 22, 2008. [⤒]

- Roland Barthes, S/Z (Hill and Wang, 1975), 16. [⤒]

- Barthes, S/Z, 16. On rereading, see Second Thoughts: A Focus on Rereading, ed. David Galef (Wayne State University Press, 1998) and Matei Calinescu, Rereading (Yale University Press, 1993). [⤒]

- Spiegelman militates against reading-as-consumption in comics like 2009's "No Kidding, Kids...Remember Childhood? Well...Forget it!," where the disgruntled Spiegelman narrator laments that being an "adult" today means having "brand preferences," so easy that no one even needs to reach the age of reason. Art Spiegelman, "Remember Childhood?" McSweeney's 33 (2009). Reprinted in Co-Mix: Art Spiegelman: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics, and Scraps (Drawn and Quarterly, 2013), 90. [⤒]

- In conversation about his spiral signature with W.J.T. Mitchell during their public conversation for the Comics & Philosophy conference at the University of Chicago, Mitchell brought up Hogarth's Line of Beauty. Spiegelman responded by noting his personal preference for Andre Breton's definition of beauty: "Beauty must be convulsive, or it must not be." Art Spiegelman, "Public Conversation: What the %$#! Happened to Comics?" Conversation with W. J. T. Mitchell. Critical Inquiry 40, no. 3 (2012), 27. [⤒]

- Gilbert Choate, "James Joyce, Picasso, Stravinsky and Spiegelman: A Portrait of the Cartoonist," Alternative Media 10, no. 2 (1978): 4-7. [⤒]

- Art Spiegelman, Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*! (Pantheon, 2008). [⤒]

- Georgiana Banita and Lee Konstantinou, "Introduction: Up From the Underground: Art Spiegelman and the Elevation of Comics," in Artful Breakdowns, ed. Georgiana Banita and Lee Konstantinou (University Press of Mississippi, 2023), 17. [⤒]

- Banita and Konstantinou, "Introduction," 17. [⤒]

- J. Hoberman, "Drawing His Own Conclusions: The Art of Spiegelman," in Co-Mix: Art Spiegelman: A Retrospective of Comics, Graphics, and Scraps (Drawn and Quarterly, 2013), 10. [⤒]

- Hillary Chute, Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form (Harvard University Press, 2016), 104. [⤒]

- While taking on the validity of this metanarrative is beyond the scope of this chapter, Cara Lewis's recent monograph, Dynamic Form: How Intermediality Made Modernism, makes a compelling case for the intermediality of modernist form. [⤒]

- See Lee Konstantinou, "Art Spiegelman's Faustian Bargain: TOON Books and the Invention of Comics for Kids," in Artful Breakdowns: The Comics of Art Spiegelman, ed. Georgiana Banita and Lee Konstaninou (University Press of Mississippi, 2023): 272-289. [⤒]

- J. Hoberman, Vulgar Modernism: Writing on Movies and Other Media (Temple University Press, 1991), 32-33. [⤒]

- Art Spiegelman, "Afterword," Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist, n.p. [⤒]

- Joseph Frank, "Spatial Form in Modern Literature: Part I," The Sewanee Review, 53, no. 2 (1945): 234-35. For all of Frank's writings on spatial form, see The Idea of Spatial Form (Rutgers University Press, 1991). [⤒]