Issue 10: The Inaugural Prize Issue

On 24 February 1984, the American poet Susan Howe gave a reading from the recently-completed manuscript of My Emily Dickinson as part of NEW YORK TALK at 300 Bowery, a series of poetry events curated and moderated by Charles Bernstein. The culmination of work she had been developing since the late 1970s, My Emily Dickinson claims Dickinson as a radical innovator who "built a new poetic form from her fractured sense of being eternally on intellectual borders."1 A significant impetus for the project came from Howe's conviction that recent criticism on Dickinson, including by feminist critics, had misrepresented her poetry by domesticating and feminizing it. Emblematic of this trend, for her, was Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar's 1979 book The Madwoman in the Attic, which imagined Dickinson's poetry as "sewing" and proposed Dickinson herself as a "Spider-Woman."2 Rejecting these characterizations, Howe insisted that the poet was "an artist as obsessed, solitary, and uncompromising as Cézanne."3 Cézanne's dedication to capturing the lived experience of perception caused him to push representation to an absolute limit and his paintings are now considered an inflection point in the history of modern art. Howe is asking: what if we understood Dickinson in a similar way? Yet the analogy also forces her to confront a non-correspondence: the troublesome fact that Dickinson's identity as a nineteenth-century woman circumscribed her art, while also, in some sense, serving as its precondition.

How does one hold these thoughts side by side in the writing of a life: on the one hand, "uncompromising" poems; on the other hand, the limitations of gender? The analogy also raises a further question: is it possible to locate this dilemma in the poetry itself? In her preface to My Emily Dickinson, Howe points to Dickinson's "carefully marked variant suggestions for wording certain poems" as one potential site to consider.4 Dickinson often reproduced different versions, or variants, of the same poem in multiple fascicles: hand-bound manuscripts she created to preserve her poetry. She also introduced alternative word choices in individual hand-written poems, signaled usually by + signs followed by the alternative word (or multiple words). These are the alternatives that Howe refers to as "variant suggestions," and which she goes on to insist are "quite deliberate."5 In the field of textual criticism, it has traditionally been the responsibility of scholars and editors to assess "which variant is the true reading and which a corruption resulting from the process of transmission."6 In other words, the existence of a variant has signified the necessity of choosing between two or more versions of a text. Yet this necessity is confounded by Dickinson, whose "variant suggestions" seemingly enabled her not to make such a choice, whether between different extant versions of a poem or between alternate word choices within a single poem.

My argument is that, in the case of Dickinson, the variant is not a problem to be solved, but a form that refuses the logic of an exclusive choice. Such an understanding also provides us with a framework for negotiating intransigent problems of interpretation that have marked critical encounters with Dickinson's poetics more generally.7 But this non-exclusive variant form cannot be comprehended without addressing the issue of the poet's gender. To put it differently, there is a question about what can be extrapolated out of the Dickinsonian model of the variant. This is the line of inquiry that Howe herself pursues in the Q&A session that follows her reading at 300 Bowery, when she links the impossibility of offering a final interpretation of Dickinson to the topic of gender. The "great thing" about Dickinson, she declares, is that one can always give "a completely opposite interpretation" of her poetry, because she "undercuts everything she says [...] so nothing has any firm meaning."8 Howe then speculates that this is not only "one of the radical things" that Dickinson "did in writing," but something "she may have done as a woman sick of hearing men, you know, like Emerson [...] talking [...] who were right and knew how to say it well." What is being debated is not whether Emerson was "right." The issue, rather, is how one might generate a poetics that disambiguates those ingrained biases that allow deliberateness to be assumed of certain persons and not others.

Yet even as Howe is clearly interested in this thought, it also appears to make her uncomfortable: a discomfort that manifests as a linguistic rowing-back of the broader feminist implications of her statement. Following her assertion that "there can be no final interpretation" of a Dickinson poem, Bernstein, in his role as discussion-moderator, asks Howe whether the lack of "firm meaning" she claims as central to Dickinson's writing is "an essential reading or feminist poetics." As I see it, Bernstein creates the conditions here for two types of response. One option would be for Howe to take his question as demanding a choice between "essential reading" and "feminist poetics." Alternatively, his use of the conjunctive "or" may imply a wish for a more open-ended response. Possibly uncertain about the precise meaning of each option, Bernstein hopes that Howe will take his "or" as an invitation to enlighten himself and the audience. Yet she parries his question, answering: "No. I don't think — there isn't — I think that has shifting values too." This language is admittedly imprecise. We're left unsure what "that" refers to: an essential reading, essentialism, feminist poetics, feminism in general, all of the above? Nonetheless, Howe's response demonstrates unequivocally that she is not willing to generalize out from the specificity of Dickinson and define what is feminist when it comes to poetry.

That this resistance is evidence of an ongoing struggle on her part to reconcile feminist politics with what it means to write poetry is particularly indicated in the final moments of her exchange with Bernstein, when he presses her once more about whether "ambiguity" is "more characteristic of feminist writing." Howe responds:

No. I think it's more. No no I think it's characteristic. I think it's great writing or fine writing is in [sic] ambiguous. But I don't. I think. No I don't. In fact. OK. Uh [brief laughter] — I'm going to get in trouble in a minute!

Listening to the recording of this conversation, I was struck by the complexity of feminist identification, discernable not only in Howe's many hesitations and acts of self-censoring, but especially in the exclamation "I'm going to get in trouble in a minute!" If we focus on the laughter that precedes this statement, we might conclude that it is made primarily in jest. Yet laughter does not mean that things are not deadly earnest, and I want to take seriously Howe's concern that she will be taken to task by some authority.

But what authority? And why? Presumably, there are people in the audience who are committed to something we might call feminist poetics. Does Howe's anxiety stem from this recognition? Might it also have to do with the fact that she identifies, however complexly, with this audience? My contention is that feminist identification itself is what is indexed so ambivalently in Howe's language here. Certainly, this identification is something that Howe is willing to claim as "hers" in certain moments, as evidenced by her critique of Gilbert and Gubar. At the same time, we might speculate that the nature of this identification is equally something that she questions (a questioning that likely makes her anxious because it may be wrongly perceived as dis-affiliation). Yet she persists — seemingly because of her sense that Dickinson has been misinterpreted as a consequence of emerging trends in feminist theory (not least a vision of the ideal feminist subject as a deliberate, sovereign self). Howe's articulated fear of getting "in trouble" may thus be read as signifying her experience of being committed to a feminist subject position, even and especially as it implies that such a commitment is a struggle, and that it is not perhaps fully hers to make.

In what follows, I take this scene of deliberation as the impetus for an examination of feminism and poetics that, rather than claiming Howe's writing as exemplary of feminist poetics, tracks its agonistic commitment to feminism through the form of the variant. This is a form, we will see, that contains within itself the possibility of self-difference and alteration. To set the scene for this investigation, I focus first on Howe's contemplation of Dickinson's writings: initially in My Emily Dickinson, but also in a 1989 interview for the magazine The Difficulties and in her subsequent essay "These Flames and Generosities of the Heart," both of which explore the feminist literary implications of Dickinson's compositional practice. I then examine Howe's poetics, making the case that a non-dualistic, deliberative variant form is also integral to her own compositions. This examination leads to a final section in which I advance a thought experiment: could the variant offer us insight into ongoing feminist political dilemmas, including debates around the "right to choose"? As evidenced by Barbara Johnson's seminal 1986 essay on apostrophe and abortion and, more recently, Clair Wills on the abortion plot, extending the resources of literary criticism to address such concerns is not without precedent. Yet the variant differs from apostrophe and plot in significant ways, and so I work, finally, to account for both literary and feminist conceptual significance of this difference. To deliberate and make decisions about our bodies, to choose where we locate them, what we put in them, and how they interact or don't with other bodies — all this is an essential part of what it means to be alive. But I will show how and why the variant encourages us to reflect on what we understand by a choice: to be aware of the conditions that make choosing possible and plausible.

1. Dickinson's Variants

What does it mean for Susan Howe to read Emily Dickinson and intervene in the burgeoning discourse of feminist criticism on this American poet in the early 1980s? Is she in some sense interpellated as a subject of feminism through her criticism of Dickinson? How might those "variant suggestions," displayed so insistently in Dickinson's manuscripts, have informed the subsequent poet's agonistic commitment to feminism? And what could they offer us still today? Whether or not Howe considered her writing on Dickinson explicitly feminist, the question of how not to do feminist literary criticism was undeniably a central preoccupation for her during the composition of My Emily Dickinson. As we have seen, she directly positions herself against Gilbert and Gubar's gynocentric recovery project while nevertheless claiming that Dickinson "conducted a skillful and ironic investigation of patriarchal authority over literary history."9 In asserting this view, Howe recasts Dickinson, not as a victim of patriarchy to be "saved" by enlightened feminists, but as a proto-feminist figure actively reconstituting the canon. Insofar as My Emily Dickinson is as much impelled by Howe's objections to extant feminist criticism as by her own feminist affiliation (though the two are of course entangled and even mutually constituting), this book is not, then, just a reassessment of a historical figure. Rather, Howe's project is in some sense primarily trained on exposing the limitations of certain varieties of feminist criticism.

Recognizing this is crucial if we are to make sense of the unresolved questions and tensions that animate this project — questions like: is "woman" how Dickinson identifies as a poet? Or did she experience it as a kind of milieu that writing poetry enabled her to get "beyond"? One way we can track Howe grappling with the problem of gender is through her vacillations between framing Dickinson's poetry in highly intentional, actional, and constructive terms and her commitment to flagging those textual instances of deliberation and indeterminacy that the reader may encounter as a kind of resistance to interpretation. Early in My Emily Dickinson, Howe tells us that "conventional punctuation was abolished [by Dickinson] not to add 'soigné stitchery' but to subtract arbitrary authority."10 I've italicized this past-tense verb to highlight the strong emphasis Howe places here on the poet's intentionality. "Conventional punctuation" is not "abolished" for the sake of it, but because thought has an aim: the eradication of "arbitrary authority" or sovereignty. By underscoring Dickinson's compositional intentionality through this verb choice, Howe implicitly calls into question editorial practices that would seek to correct Dickinson's grammar — that is, to domesticate it, with all the gendered associations therein — and in so doing undercut her authority as a poet.

Yet a tension exists between this rhetoric (of choosing, inventing, building, and abolishing) and Howe's frequent attention to moments of textual deliberation and refusals to choose in Dickinson's poetics. We can observe the latter in passages like the following:

a "sheltered" woman invented a new grammar grounded in humility and hesitation. HESITATE from the Latin, meaning to stick. Stammer. To hold back in doubt, have difficulty speaking. "He may pause but he must not hesitate" -Ruskin.11

Again, there is an initial emphasis placed on Dickinson's capacity to make something "new." But invention of what? Of a grammar that sticks and stammers, that "holds back" in a manner that contravenes the directive of Ruskin, whose implied understanding of hesitation as an exclusively female-gendered (or non-male) form of failure is repeatedly unsettled in My Emily Dickinson. At issue is how society genders what it perceives to be moral or intellectual defects. Could acknowledging, rather than repressing, hesitation be worth the trouble it causes? What happens when we face such moments, not as solutions, but as non-negotiable partners of making, abolishing, and choosing? What form might such an encounter take?

In a 1989 interview published in the magazine The Difficulties, Howe gives us one answer to this final question: Dickinson's worksheet draft for her poem "Summer — we have all seen —", replete with multiple variant word choices and cancelled language. I have reproduced Howe's transcription of the worksheet (included in The Difficulties interview transcript) below, which shows Dickinson working out the poem's final stanza:

This poem draws on the lyric theme of a cold and unresponsive beloved. Ostensibly, its object is a season, though nature may stand in for some unspecified despotic other who "does not care" despite being "unquestionably loved." My claim is that the variant form is critical to the development of this poem, as well as to an understanding of Dickinson's more existential preoccupations here, which involve an inquiry into relations of power, desire, and control. Below is the poem (including variant words) as presented by Cristanne Miller:

line 6: [She] goes [her] spacious [way] • her ample way — • She goes her sylvan way —

• [She goes her] perfect • spacious • subtle • simple • mighty • gallant [way]

lines 7-8: As undiverted as the Moon from her Divinity — • As unperverted as the Moon /

By Our obliquity — • As eligible as the Moon — to our extremity — • Adversity —

lines 9-10: Created to adore — / The Affluence evolved — • conferred — • bestowed —

• involved —

These lines were composed in 1876, the year that Dickinson stopped copying her poems onto formal sheets of stationary and collecting them in fascicles and sets. As Dickinson scholar Alexandra Socarides notes, she also "did not destroy drafts in the way she had become accustomed to doing," so we are left with work that includes many variants, particularly towards the endings of poems.13 Dickinson editor R.W. Franklin refers to the late drafts as "a proliferating disarray of scraps of paper," and Dickinson editor Thomas Johnson describes the draft for "Summer — we have all seen —" as "one of her most chaotic."14 If Emerson "knew how to say it well," Franklin and Johnson imply that Dickinson has forgotten what she knew and is now saying it wrong

Yet in her Difficulties interview, Howe objects strongly to Johnson's language, declaring instead that the worksheet draft raises "complex questions about control and controlling."15 To describe the worksheet draft as "chaotic" is symptomatic of the way that Johnson approaches Dickinson more generally: as oriented towards the lyric product or artifact. Howe doesn't accept this approach — not, as I understand it, because she has reversely committed herself to privileging drafts over "final" poems, but for two different reasons. The first has to do with the topos of poetry, understood loosely as both its topic and the space of the page it inhabits. Howe's counterclaim that the draft generates "complex questions about control and controlling" implies that Dickinson's variants and strikethroughs participate in the poem's topos, insofar as they thematize the same kinds of questions about control as what emerges over the course of the full three-stanza lyric. Who is "deputed" to adore and who is doing the deputing? Why, how, and with what is "the Embryo endowed" (a mysterious phrase that raises questions about the control of pregnant bodies and fetuses, as well as what counts as a life, to which I will return)? The second reason that Howe cannot accept Johnson's characterization of this draft as "chaotic" has to do with how the page implicates the life of the world. It's not that she is asserting no separation between word and world when she highlights "questions of control and controlling." But nor, she suggests, is the draft unresponsive to myriad forms of coercive relation typical of nineteenth-century American life. We might then understand those hesitations and deliberations that compose this draft as in some sense enacting the sense of a loss of control that permeates daily experience — of living in a condition in which one has no "good" choices.

They can equally be read, however, for the evident intensity of self-reflexive activity that they mark, particularly insofar as we understand them as constitutive of a poetic process. This is indicated by Dickinson's crossed-out "Contented". Evidently, "Contented," which evokes directionless plenitude, is rejected here by Dickinson in favor of "Deputed," a term that implies an authority with the power to delegate and dictate. This substitution shows the poet reaching for more potent imagery by working through break-down, represented literally by the strike-through. Yet the deputing capacity of any authority is arguably complicated by the obscured presence of "Contented," which functions as both a negation and a statement. Certainly, it is not a variant in the traditional textual critical sense. At the same time, "Contented" alerts us to the possibilities that arise when the variant is approached, not as a problem to be solved, but as an invitation to reflect on the conditions of deliberation, the difficulty of acting in the world, and the contexts that make choosing possible or not in the first place.

To accept this invitation also allows us to cast off a stifling binary when it comes to Dickinson: the work as either intentional lyric product or aestheticized residue. Approached from this perspective, what counts as a poem also becomes more porous and unstable, and it is this porosity that Howe makes the focus of her later criticism on Dickinson. In her 1991 essay "These Flames and Generosities of the Heart: Emily Dickinson and the Illogic of Sumptuary Values," Howe narrates the story of a charged epistolary exchange between herself and R.W. Franklin. In 1981, Franklin, in his capacity as editor, published The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson. As its title suggests, the Manuscript Books transformed access to Dickinson's archive by presenting facsimiles of all her manuscript books (or fascicles), as well as her unsewn fascicle sheets, in book form. For Howe, the Manuscript Books offered a radically new perspective on Dickinson's poetics, leading her to write a letter to Franklin in 1985 in which she observed that "after the ninth fascicle (about 1860) [Dickinson] began to break her lines with a consistency that the Johnson edition seemed to have ignored."16 It seems, more particularly, that she wrote to Franklin because she knew that he was editing a new variorum edition of Dickinson's poetry (subsequently published in 1998). Perhaps, her insight would encourage him to account in this project for what appeared to be a significant shift in Dickinson's compositional practice. Yet Franklin offered only a "curt" response, which she paraphrases as follows:

He told me the notebooks were not artistic structures and were not intended for other readers [...]. My suggestion about the line breaks depended on an "assumption" that one reads in lines; he asked "what happens if the form lurking in the mind is the stanza?"17

For Howe, the implicit irony is that Franklin counters what he assumes to be her "assumption" with an additional assumption of his own: that the form lurking in the mind is the stanza. And though here Franklin leaves room for doubt, we will see that his actual editorial decisions resolve this doubt.

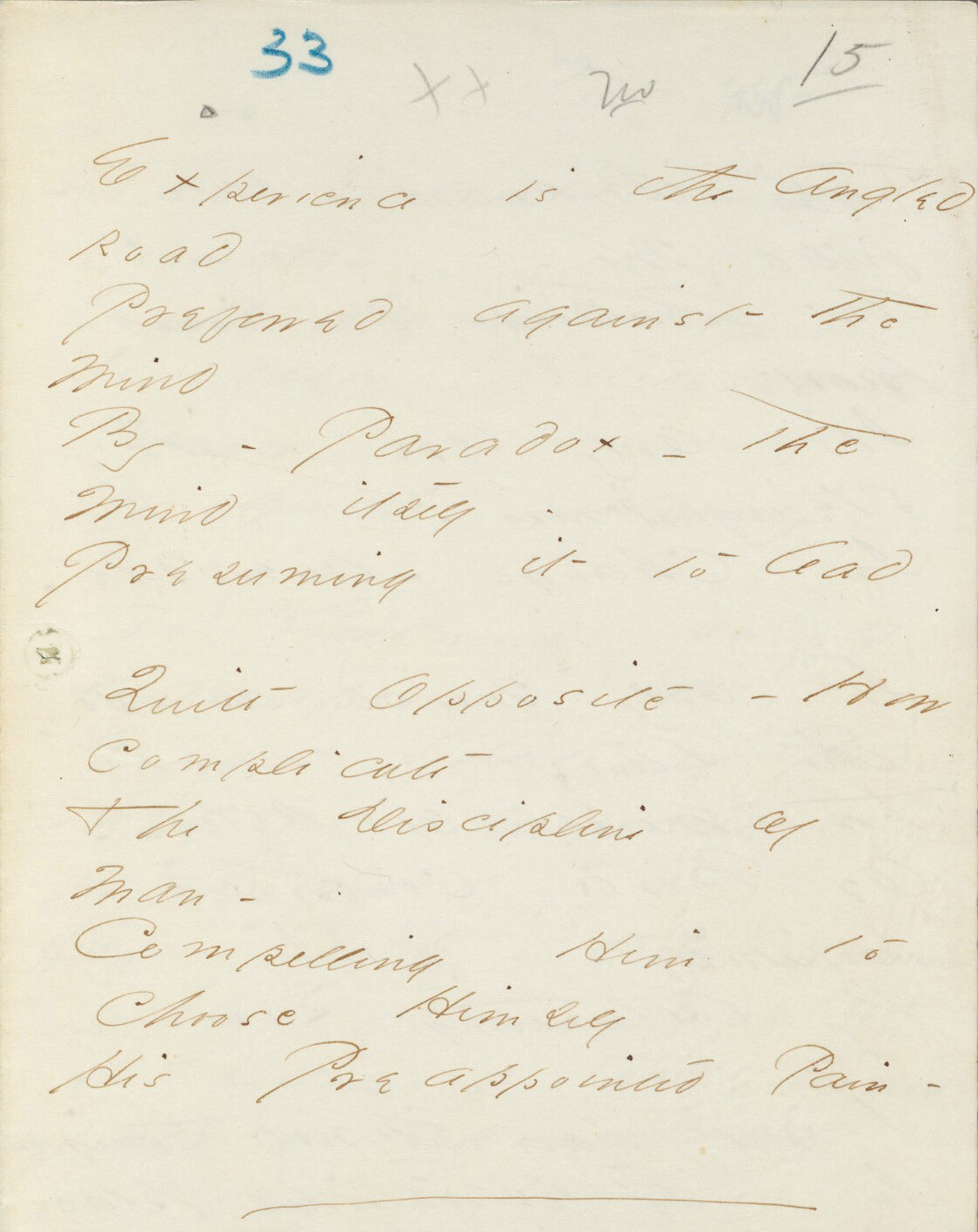

If the line-break is increasingly central to Howe's understanding of Dickinson's form, this centrality is not because she is only or primarily reading in lines, but rather because she approaches the line-break as a circumscribed choice: an index of "complex questions of control and controlling." That Howe is thinking in this way is particularly suggested by the typographical transcription she makes in "Flames and Generosities" of Dickinson's poem "Experience is the Angled Road," which she places alongside a facsimile of the handwritten manuscript.

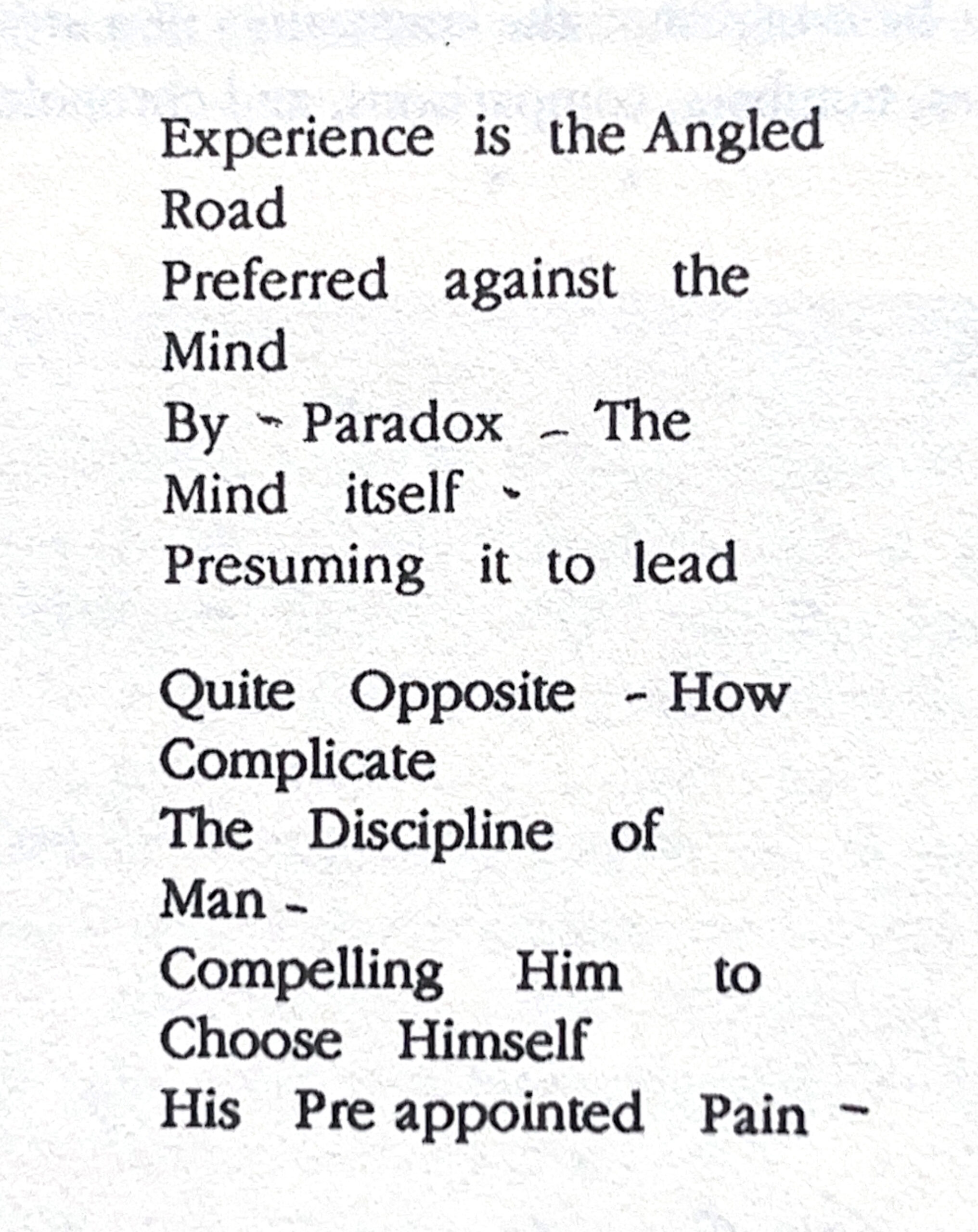

Howe's transcription presents a marked contrast to how Franklin eventually formats the poem in his 1998 variorum edition:

Experience is the Angled RoadPreferred against the MindBy — Paradox — the Mind itself —Presuming it to leadQuite Opposite — How ComplicateThe Discipline of Man —Compelling Him to Choose HimselfHis Preappointed Pain — 18

Reading Howe and Franklin's transcriptions of this poem against each other is an illuminating exercise, not least because that "mind" to which Franklin refers in his exchange with Howe is equally Dickinson's subject. This poem explores how we may experience our own lives as at once self-chosen and shaped by an external power, force, structure, or institution. It is precisely this issue that returns us to the poem's mis-en-page, and to those varying presentations of "Experience is the Angled Road" offered by Franklin and Howe. For Franklin, a predetermined metrical limit (common meter) governs his decisions about where to break Dickinson's lines. However, given that a dialectic between "Mind" (as abstract instrument or structure) and the "Angled" journey (of concrete, lived "Experience") semantically governs the poem's opening stanza, we might go so far as to read this dialectic as materialized in the manuscript's enjambments, which work against our capacity to read the poem as straightforwardly conforming to common meter.

Howe's reading certainly suggests as much. In one sense, we can interpret her decision to adhere to Dickinson's presentation as part of an effort to claim her as a modernist progenitor whose idiosyncratic practice anticipates free verse's privileging of the unit of the line over that of the stanza. At the same time, Howe is recognizing an intractable dilemma enacted through the poem's topos, which has to do with will or intentionality. If the poem stages a hesitation over the nature of agency and individual choice, her version, by retaining Dickinson's line breaks, allows us to see that this hesitation is equally inhabited in the extended moment of composition. We are invited to read the poem as a meditation on the ways in which the poet at once chooses and is compelled to choose.

A subsequent letter that Franklin sent Howe gives further insight into his editorial assumptions. In it, he asserts that if he were editing Dickinson's correspondence he would be willing to "use run-on treatment" because "there is no expected genre form for prose," whereas "there is such a form for poetry" that he intended to follow, "rather than accidents of physical line breaks on paper."19 Franklin's choice of "accidents" to describe Dickinson's line-breaks is telling, and, in light of the existential dilemmas posed by "Experience is the Angled Road," ironic. It is a word that implies an ontological difference in which the concept ("Mind") has greater reality than its tangible or empirical manifestations ("Experience"). It also denies the possibility that the scene of composition, including material contexts, could have had any significance for Dickinson's negotiation and understanding of her own meaning. What I would then emphasize here is that those difficult questions of intentionality, control, and controlling that Howe orients us towards in her Dickinson criticism — and which we will shortly encounter as readers of her own poetry — are also uncannily refracted in contemporary feminist discourse that takes as its subject the gestation of persons rather than poems.

2. Howe's Variants

What happens when our ability to determine what counts as a poem is suspended or called into question? Howe's correspondence with Franklin reveals that coming up against such withholding as a critic or editor is a fraught experience. What might initially appear to be a limited question of a line-break or crossed-out word can open up a chasm of ambiguity. Franklin, we saw, was unwilling to face this chasm. Indeed, he seemed to believe that the type of acknowledgment Howe asked of him was at fundamental cross-purposes with his responsibilities as Dickinson's editor. Howe, it seems, views Franklin as nothing less than the living embodiment of "assumptive privileged Imperative." Yet his intimation that she is the one making assumptions about what's "in" Dickinson's mind suggests that he experiences himself more as bound to a deputing source than a sovereign authority. To be clear, I am not proposing that Howe is wrong in her assessment. The point to emphasize, rather, is that responsibility returns us to the issue of intentionality, raising questions about which persons can be deemed responsible, for what, and why. That these are feminist issues will become especially evident in the final section of this essay, when I turn from poetic intentionality to what it means to be seen to choose, or not choose, in the world. In addressing Howe's own poetry, I lay the groundwork for this turn.

Here, my argument is that Howe's poetics is a poetics of the variant, and that this poetics indexes an agonistic commitment to feminism. Earlier, I claimed that to be committed in this way is never wholly the poet's decision. I also drew on Howe's ambivalent language at 300 Bowery to propose that feminist identification is both something in which she is invested and a problem that she questions. It is this identification that we saw manifest as a lived tension in Howe's public speech, indexed through a range of conflicting performative effects (hesitation, assertion) and affects (anxiety, laughter). I propose that the same lived tension takes us to the heart of her poetics.

Like Dickinson, Howe's poetics refuses the normative textual-critical logic of a mutually exclusive choice. We see this at every level of poetic production: letter, word, line, stanza (or segment), page, double-page spread, book. In her poems, fragments of words like "wolv," sa," "wal," "wov, and "chronicl" invite different possibilities for completion, yet resist closure.20 Sometimes, a wrong or unconventional spelling, often implicitly archaic, is used to generate a similar effect: "The snow / is still hear // Wood and feld / all covered with ise."21 If we doubted that homophonic confusion between "here" and" hear" was being deliberately activated by the poet, additional unconventional spellings — "feld," "ise" — reinforce a sense of purposiveness.

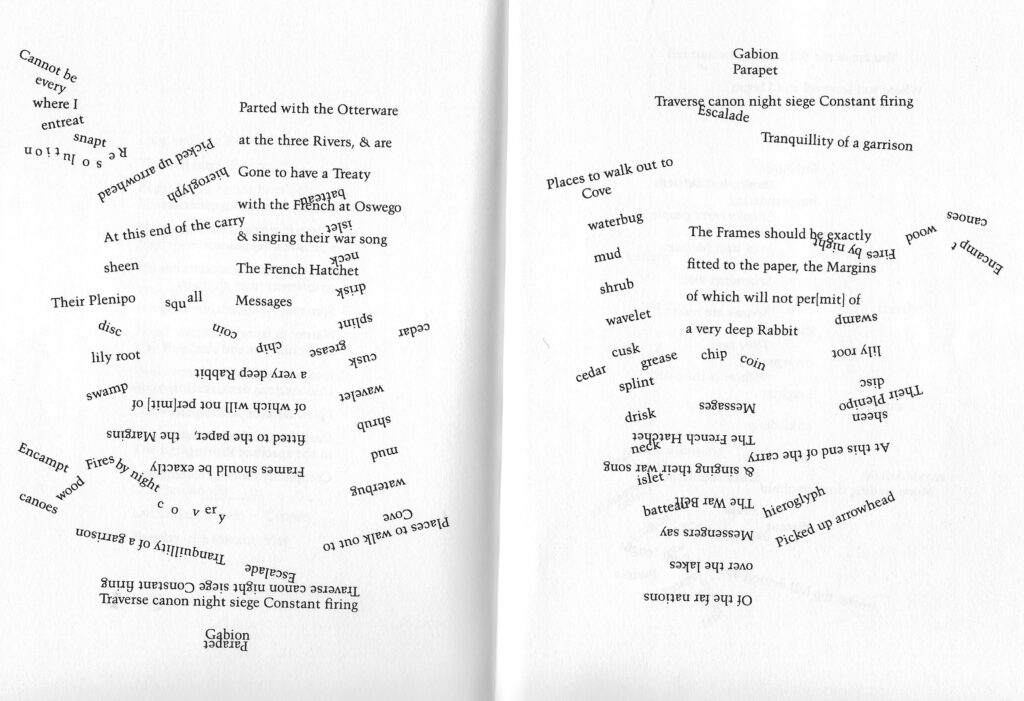

While the variant animates Howe's poetics most obviously at the level of the individual letter (and, by extension, word), this level is also porous, placing pressure on all that lies around it: a pair of lines, a stanza or short segment, an entire material page. In poems of the later 1980s and 90s, including "Thorow," whole pages are rotated 180 degrees so that the experience of reading becomes, somewhat unexpectedly given the initial sense of overwhelming disorientation, a deliberative practice of comparison between recto and verso.

This would be a disappointing exercise if it turned out that the two pages were the same aside from being oriented differently. However, this is generally not the case, as becomes clear when we focus on the upper left-hand corner of the verso page, which includes a phrase not reproduced in the recto spread ("Cannot be / every / where I / entreat / snapt"). It is helpful in such moments to attend to the inversion of specific words as points of orientation, or indeed anchor variants, that help the eye to grapple with what is unfolding:

GabionParapetGabionParapet

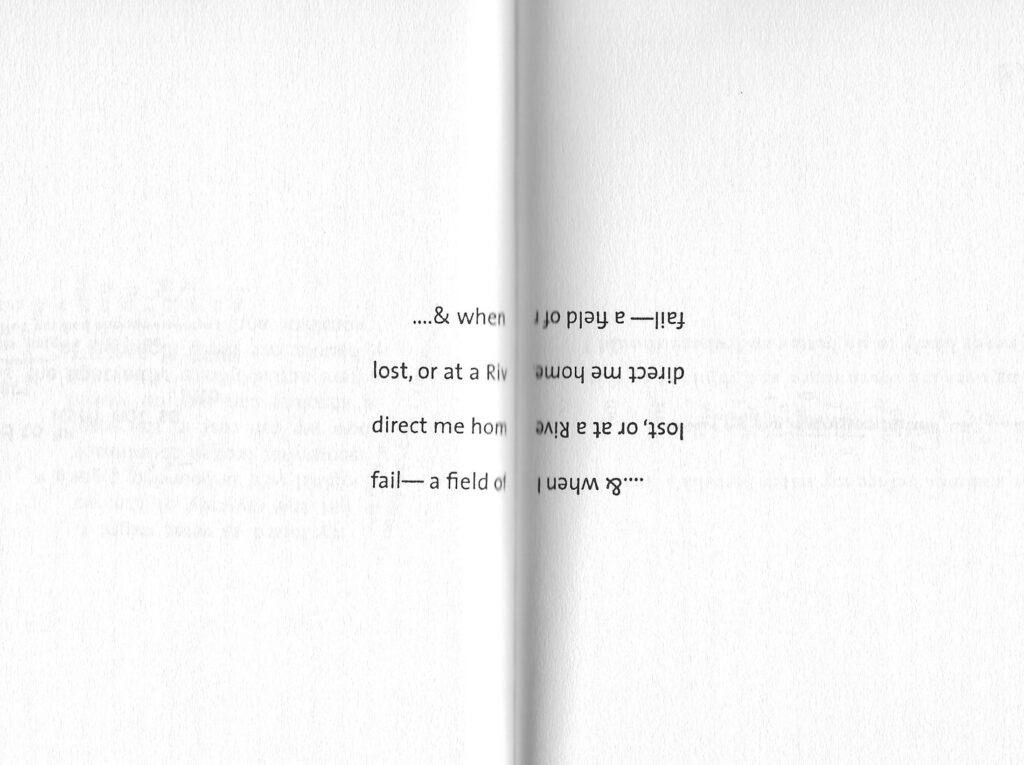

That the reader is encouraged to do this additionally raises issue of the seam or interval (what we might understood as the variant's conceptual precondition), which Howe especially explores in her writing of the 2000s and 2010s.

The above spread, taken from Howe's 2010 poem "Frolic Architecture," highlights the paradoxical nature of the seam, understood as that which divides but also knits together. Insofar as it composes and, in some sense, settles or sets the image, this seam also ambivalently marks a potential source of the variant's erasure. For where one set of language comes up against another, there is the promise of a whole, despite the fissure that remains apparent.

A preoccupation with seams and intervals is likewise observable in Howe's 2001 poetic sequence "Bed Hangings I." In a short discursive text that precedes this sequence in her 2003 collection The Midnight, she notes: "There was a time when bookbinders placed a tissue interleaf between frontispiece and title page in order to prevent illustration and text from rubbing together."22 In "Bed Hangings I," she turns her attention to the interleaf as it materializes in the world, exploring parallels between this form and aspects of domestic space, including the textile "eyelet" (a cotton fabric usually associated with women's clothing; also a method of hanging curtains), which she describes as a "pierced interval":

Example reveals pierced intervaleyelet holes though admittedly ifemblem tossed it lends progressa corporeal incorporeal European23

This textual moment is far less visually disorienting than what we encounter in "Frolic Architecture." Yet the pierced interval still marks a transitional space: a zone of contention that provokes curiosity. What's behind? Or, from a different perspective, beside?

The cancelled, withheld, displaced, or failed choice; the circumscribed choice; the choice that orients or disorients; the alternative that persists or elaborates; the pierced interval: these are formed aspects of a poetics of the variant. They also contribute to the opacity of Howe's style, which I experience as first and foremost an intractability or resistance to being read — though Howe is also noticeably careful about framing, contextualizing, and, in certain cases, qualifying those textual moments that appear most intractable.24

Arguably, a resistance to being read manifests especially through techniques that disturb "the visible surface of discourse" (and in doing so pose deliberative challenges for the reader), even if the poet continues attending rigorously, even obsessively, to that surface.25 The consequences of these techniques are clarified by the idea of "antiabsorption" developed by Charles Bernstein in his 1990 essay "Artifice of Absorption." Bernstein frames antiabsorption (associated with qualities ranging from "artifice," "unintegrated," "mannered," and "ironic" to "doubt" and "noise") and its apparent opposite (absorption) not as fixed aesthetic modes, but as dynamics of reading.26 Consequently, he argues they "should not be understood as mutually exclusive," but "connote colorations rather than dichotomies."27 The idea that absorption and antiabsorption are not "mutually exclusive" but constitute a more complex readerly dynamic is borne out in the Howe, whose intractability has a great deal to do with her own readerly sense of foreclosure — that she cannot access those historical contexts or subjectivities towards which she reaches. We see this especially in "The Liberties," a poetic sequence that she composed in the 1980s.

"The Liberties" is structured around two female figures, who can be understood as variants of each other: Esther (Stella) Johnson, life-long companion of Jonathan Swift, and Shakespeare's Cordelia. Given that both Stella and Cordelia resist cultural expectations of femininity within the family, one is encouraged conclude neatly that "The Liberties" stimulates the conditions for a rewriting of history as "herstory." Yet "The Liberties" is also a more agonistic poem than meets the eye. On the one hand, its discursive opening section "Fragments of a Liquidation" embodies a normative historiographical practice, foregrounding verifiable facts relevant to Stella: "When Sir William Temple died in 1699, he bequeathed to Esther Johnson 'a lease I have of some lands in Morristown, in the county of Wicklow in Ireland'."28 Yet a second prose section, "Stella's Portrait," asks us to be more skeptical about what it means to produce a narrative of female empowerment out of disjointed bits of information culled from the archive. "No authentic portrait exists," the reader is told.29

What methods can be used to interrogate these limits of the archive and question the production of history as writing? In the period when Howe was starting to probe these questions, Joan W. Scott was addressing the same issues in a series of essays that would later become her influential 1988 book Gender and the Politics of History. Scott understands history as an institution that produces knowledge. But she asserts that it's also "inevitably, about sexual difference."30 "It has not been enough," she argues, "for historians of women to prove either that women had a history or that women participated in the major political upheavals of Western civilization."31 Rather, feminist history must work to expose "the often silent and hidden operations of gender that are nonetheless present and defining forces in the organization of most societies."32 Scott recognizes that the former approach, which she terms "herstory," is very common among feminist-identifying historians. Yet the danger, she cautions, is that herstory ends up reinforcing a logic of separate spheres it had thought to challenge — the same logic that Howe resists at 300 Bowery, and which she likewise troubles in "The Liberties" through a poetics of the variant.

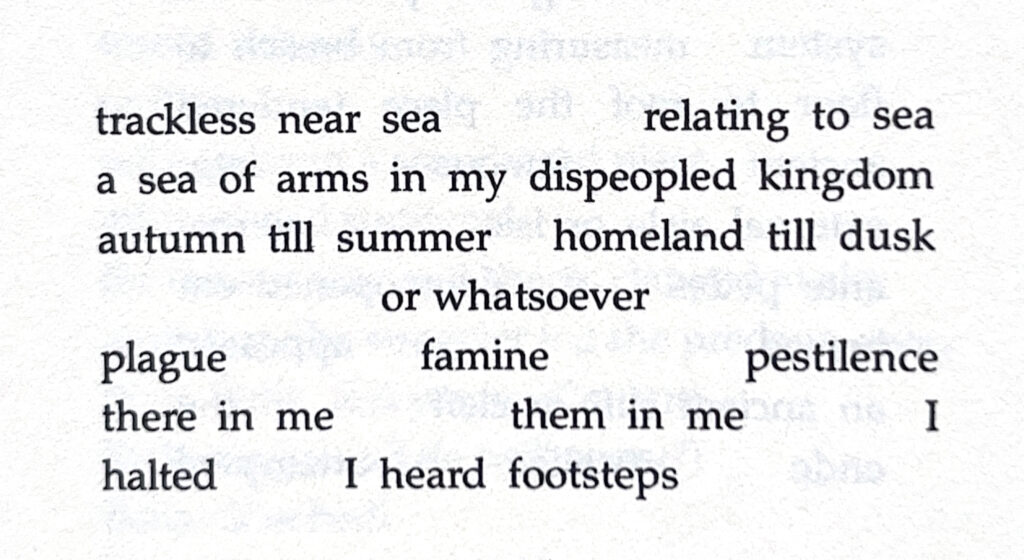

A resistance to this logic is especially evident in the more formally disorienting sub-sections that together make up the first part of "The Liberties": "THEIR: Book of Stella" and "WHITE FOOLSCAP: Book of Cordelia." Consider the role of the conjunctive "or," which occurs repeatedly in "THEIR / Book of Stella." While it signifies the presence of an alternative, it also marks the possibility of displacement, withholding, and substitutability:

The above passage suggests that this poem is wary of recuperating marginalized voices by emphasizing their rational capacity to will and act. In contrast to the melodrama that often accompanies accounts of tragedy, the central, structuring phrase "or whatsoever," associated with a passive lyric subject, places the reader in a context in which the ability to choose is withheld, leading to the equation of one form of tragedy with another: "plague," "famine," pestilence." This raises the disconcerting thought that the variant may be as much a symptom of paralysis and social breakdown as an opportunity for thinking otherwise. Hannah Arendt argues that whatever we may imagine ourselves to deliberate upon and decide in our minds, this mental effort cannot be called free from a political perspective unless it is coincident with action in the world: "Men are free as distinguished from their possessing the gift for freedom—as long as they act, neither before nor after."33 In "The Liberties," the variant raises the question of deliberation that fails to become action in this sense: deliberation that remains internal, that cannot be associated with external signifiers of deliberateness.

In her 1987 poem "Articulation of Sound Forms in Time," which centers on a Puritan minister implicated in a 1676 massacre of Native Americans, Howe writes of a "Migratory path to massacre / Sharpshooters in history's apple-dark"; and of "Collision or collusion with history".34 In offering these phrases, she is, I imagine, at least partly addressing herself to herself, confronting her own practice ("collision or collusion"?). Critics have acknowledged the ethical ambivalences of Howe's project and sought to articulate a resistance to the seductions of her work (which the work itself is also sometimes) claimed as counteracting.35 There has also been an impulse to celebrate Howe's work as a project of recovery, which we often find in feminist accounts of her writing. Yet Howe's poetics of the variant is at odds with a more liberal celebration of female agency, a fact that critics who focus on the role of feminism in Howe's work have sometimes elided.36 An exception here is Rachel Blau DuPlessis. In a carefully modulated passage from her essay "Whowe," she observes:

Howe continually proposes at least a feminism of cultural critique while declaring strong opposition whenever she suspects unitary (undialectical, uncritical) feminist enthusiasm. The only danger is that Howe's precise kind of feminism may be misread by a- or anti-feminist commentators.37

This statement captures something essential about Howe's poetics. DuPlessis recognizes that her resistance to "undialectical" feminism does not mean that she is questioning the need for feminist reckoning. The question is how to do it. DuPlessis intimates that such a practice — or praxis — must be dialectical. She does not claim that Howe offers us a unified feminist method, but rather suggests that her poetics is dialectical in the sense offered by Frederic Jameson in his Valences of the Dialectic: it "offers a rebuke of established thought processes (such as an inveterate confidence in the law of non-contradiction)."38 Indeed, my argument in the preceding pages — that Howe's poetics is a poetics of the variant — amounts to a claim that the variant is a form that, by definition, undercuts "inveterate confidence in the law of non-contradiction." In what follows, we will see that it is something akin to this "confidence in the law of non-contradiction" that has generated such intractable problems for feminist discourse, particularly within the context of abortion debates.

3. Responsibilized Subjects and Para-Literary Form

It is understandable that the idea of the deliberating and deliberative self, capable of reflecting, willing, and judging, has been taken up by contemporary feminism as central to its aspirations and values.39 It makes even more sense when we remember that modern feminism emerged precisely in relation to a developing political discourse of individualism and individual rights that promoted democratic principles like liberty and equality: principles that eighteenth-century republicans sought to enshrine as rights by law. That the "right to choose" has remained such a rhetorical lightning rod over the past half-century — a phrase inextricable from the ongoing abortion debate, ardently defended by liberal and many left feminists and opposed by the religious conservative right — is a direct consequence of this history. But the premium placed on choice as such within the feminist movement may paradoxically be keeping us from asking important questions about this so-called "right." Where does it come from? By whom or what is it conferred? Who is accorded this right and who does it exclude? How might it condition our ideas about what it means to choose in the first place?

So far, I have used the framework of the variant as a way to probe established ideas about poetic composition, textual editing, and the production of history. I have also suggested that the form of the variant is relevant to a feminist questioning of the politics that underlie the discourse of liberal individualism. In this final section, I ask: can the variant help us to expose limitations and paradoxes inherent in a discourse of rights that arguably coalesce in the formulation "right to choose"? More particularly, could it allow us to challenge the responsibilization of pregnant persons as moral agents (with "sovereignlike power over human life"), as well as the "proleptic structure" that pregnancy narratives often take on (in which the fetus is treated "as a separate 'baby-person' already, even a citizen bearing rights")?40 Admittedly, these two versions of pregnancy would appear to run counter to each other: on the one hand, the pregnant person must embody the reproductive ideal of maximal agency, even and especially if they choose to have an abortion; on the other hand, they are interpellated as a passive container or incubator for future life. Yet it is not at all surprising that these conflicting narratives coexist; our investment in pregnant subjects has never been rational. In fact, this is where our prior discussion of a poetics of the variant may offer us assistance—reminding us that what appears to be an impossible choice may be something rather different.

It may seem, here, that we are straying too far from literary criticism. There are compelling reasons, however, for approaching the abortion question through a literary lens, and I am not the first critic to assert this position. In 1986, Barbara Johnson published her seminal essay "Apostrophe, Animation, and Abortion," and in March 2023, Clair Wills's essay "Quickening, or How to Plot an Abortion" was published in the London Review of Books. Both essays suggest that what constitutes a choice is called into question by the experience of abortion, and both depict abortion as a potentially depersonalizing experience undergone by an agent who is "not entirely autonomous."41 Each also insists that literary form can give us insight into the abortion debate. If the dominant analytic approach of abortion ethics adopts a framework that positions the pregnant person and fetus "as separate individuals, even adversaries, with rights that need to be weighed against each other," these essays, in contrast, encourage us to ask: what happens if we attend to the unpredictable consequences of embodied subjectivity for choice?42

"Apostrophe, Animation, and Abortion" builds towards a close reading of Gwendolyn Brooks's "The Mother," a poem, in Johnson's words, that "suggests that the arguments for and against abortion are structured through and through by the rhetorical limits and possibilities of something akin to apostrophe."43 Its opening line — "Abortions will not let you forget" — figures "Abortions," in Johnson's words, as "capable of treating persons as objects."44 This dehumanizing capacity is reflected in the poem's deferral of its lyric aim; it is only in the second stanza that its structure of address changes and the mother apostrophizes her "dim killed children":

I have said, Sweets, if I sinned, if I seizedYour luckAnd your lives from your unfinished reach,If I stole your births and your names,Your straight baby tears and your games,Your stilted or lovely loves, your tumults, your marriages, aches, and yourdeaths,If I poisoned the beginnings of your breaths,Believe that even in my deliberateness I was not deliberate.45

Johnson interprets this passage as presenting us with a situation in which the speaker "assumes responsibility" for a death while remaining unsure "of the precise degree of human animation that existed in the entity killed."46 I'd add that we might also identify in these lines an attempt by the speaker to qualify her responsibility: even in my choosing I was not choosing.

Johnson goes on to observe that the "association of deliberateness with human agency has a long (and very American) history. It is deliberateness, for instance, that underlies that epic of separation and self-reliant autonomy, Thoreau's Walden."47 Yet she notes that, for Thoreau, "pregnancy was not an essential fact of life."48 The relevant point is that Thoreau's capacity for deliberateness is premised, by his own account, on separation from others, whereas that of Brooks, as we have seen, is shaped by an experience of not being separate or singular. What Johnson is curious about, then, is how "the plot of human subjectivity" could be "reconceived (so to speak) if pregnancy rather than autonomy is what raises the question of deliberateness."49 This thought leads her to conclude:

It is often said, in literary-theoretical circles, that to focus on undecidability is to be apolitical. Everything I have read about the abortion controversy in its present form in the United States leads me to suspect that, on the contrary, the undecidable is the political. There is politics precisely because there is undecidability. 50

Crucially, Johnson's point here is not that political questions cannot be decided one way or another (recent court rulings and strong dissenting opinions show that we in fact live in an era of constant relegislation), but that there is politics because there is undecidability.51 When does a being assume "a human form"?52 What does it even mean to seek to make such a determination? What if we can't? Who is authorized to make decisions about our bodies and why?

The concept of undecidability returns us to the scene of composition that has been the focus of this essay, and to the issue of whether an exclusive decision is required in the first place. It also raises the question: Is any choice made in an "undecidable" situation necessarily a tyrannical one? Arguably, we already encountered a version of this question (and an answer) in the form of Howe's criticism of Franklin's refusal to reproduce Dickinson's lineation in his variorum edition of her poems. But the question is transposed now into the realm of the political life with all that that entails. It seems to me that one of the problems that the abortion question forces into the open is precisely this: that one finds oneself in a situation in which one can't not choose even though one is faced with a decision that's in some sense undecidable. This, arguably, is the circumstance described by Brooks when she writes: "Believe that even in my deliberateness I was not deliberate."

It is this problem — of becoming, against or without one's choosing, the subject of a tyrannical choice — that Clair Wills confronts in her essay "How to Plot an Abortion."53 Wills begins with a reading of Annie Ernaux's 1973 novel Les Armoires vides, which is structured around the abortion of its main character, Denise, a fictionalized Ernaux. Early on, Wills reminds us that "abortion is not legal in the UK," a fact that Labour MP Stella Creasy has likewise emphasized in the wake of the recent prosecution of a British woman for her late-term abortion: "The conviction that we have seen [...] shows that it is not a theoretical issue to consider whether women in England and Wales have a legal right to an abortion. They don't. They have a situation where they are exempted from prosecution."54 It is the illogic generated bythis "situation" that Wills underscores in the following passage:

When you access an abortion, you are asked to take on the role of a character making a choice, full of thoughts and feelings that are explained and then justified: you are asked to tell a good story. The stories — the ones asked for by our legal structures — are compulsory. Indeed, they are life-saving. But if you try to fit your experience to a legal definition of rights, you are going to be telling the wrong story.55

Understood in this way, one can't not tell the "good story" of your choice and have a legal abortion. A choice must be "explained and then justified" in order for an exception to be made. In other words, the narrativization of choice is what sanctions the "right to choose." And yet, Wills observes, abortion stories are not usually written in a way that calls attention to this fact: "The stories are about how, not why, and definitely not whether. They are grubby stories of female abjection at the hands of the law."56 Ernaux, she notes, was active in the campaign group Choisir in the 1970s, which advocated a woman's right to choose. Nonetheless, "everything about Les Armoires vides suggests that Denise can't and doesn't make choices. Her life is determined by her milieu. [...] She's been 'fucked from all sides', as she puts it, betrayed by what Bourdieu would call her 'disposition'."57

In this way, Wills urges us to question what it means to (have to) produce authorizing speech. How am I saying that I'm choosing? Is this saying really choosing? Wills insists that you're "telling the wrong story" if you try to "fit your experience to a legal definition of rights." Her analysis urges us to confront the fact that the abortion seeker is compelled to tell the story of their choice in order to be "allowed" to choose. In doing this, it exposes the harm that resides in the ideal of maximal reproductive agency, which neither Ernaux's abject protagonist nor Brooks's conflicted speaker can embody despite their responsibilization as pregnant subjects. Indeed, these figures are valuable models for "pro-choice" feminists precisely because they flag the insufficiencies (though not the dispensability) of a discourse of rights when it comes to articulating a politics of reproductive justice. Brooks's use of the form of apostrophe and Ernaux's deployment of plot allow these authors to position their subjects in terms that are conflicted and caught. In other words, if women are constituted as responsibilized subjects through their association with a principle of life imagined as symbiotic with self-sovereignty, literary form reveals such symbiosis to be, in Penelope Deutscher's phrase, "pseudo."58

This point bears emphasizing: those choices (which can equally be read as not choices) made by Ernaux's Denise and Brooks's unnamed lyric speaker are not actions in the world, but rather representations that take shape as actions through the workings of literary form: an idea that raises the question of how the variant relates to apostrophe and plot. Earlier I called attention to Johnson's assertion that the abortion controversy is evidence that "there is politics precisely because there is undecidability." This statement leads in the essay to a passage that arguably crystallizes her project's stakes:

There is politics precisely because there is undecidability.And there is also poetry. [ . . . ]59

Here, Johnson uses the conjunction "And" to begin not just a new sentence, but a new paragraph: an unusual paratactic move for an academic essay. My speculation is that Johnson self-consciously makes this move because she is attempting to pull herself back to the problem with which she began — the presumption of rhetoric's apoliticism — and counter this presumption through the deployment of her own rhetoric: that is, by doubling down on the essay's topic. Her striking syntax knits the lived and the literary together, even as it enacts a separation between them. The rhetorical claim is for non-coincidence and correspondence: for a difference that does not cancel out the need to hold "poetry" and "politics" together in the balance.

I would like to pursue the implications of this thought by articulating what I understand to be an important difference between the variant, on the one hand, and apostrophe and plot, on the other hand. Certainly, there are similarities between these forms. Each enables us to represent aspects of reality in ways that would otherwise not be possible. Yet apostrophe and plot tend to be viewed as typical of, even defining, specific modes of literary production. When pressed by an authority to explain one's need for an abortion, one is more likely to summon a linked sequence of events that could be called a plot. Similarly, it is difficult to imagine a lyric devoid of some invocation of an absent or inanimate addressee, however ironic or bathetic. A classic formulation that articulates this position is Jonathan Culler's claim that one might be "justified in taking apostrophe as the figure of all that is most radical, embarrassing, pretentious, and mystificatory in the lyric, even seeking to identify apostrophe with lyric itself."60 Whereas the variant, as I have theorized it, is not associated with a specific mode of literary production, because it has no predetermined content or, perhaps more accurately, intended object. I do not mean that it has no meaning, but that it's similar to the condition of a grammatical shifter. To be sure, there are different kinds of emplotments (marriage plot, Bildungsroman, tragedy, romance) that may be deemed more or less adequate for representing a given set of events, as well as potentially infinite possible candidates for apostrophe (wind, lovers, children, rocks, flowers, birds, clouds). But not only is every instance of the variant different, the question of what it implicates cannot be decided in any way in advance.

If we accept that apostrophe and plot are literary forms, it might then be more appropriate to characterize the variant as a para-literary form. Para, from the ancient Greek παρά, is one of the more ambivalent prefixes, possessing multiple, even conflicting meanings: beside, adjacent, next to (parallel); surrounding or throughout (paracerebral); but also against, opposite, or contrary to (parasol); also, potentially, beyond (paranormal, paradox); even false, incorrect. Is para less than or more than? To the side or everywhere? Near or false? To be sure, from the outset I have acknowledged that the variant is associated with a long tradition of studying and editing literary texts, an association that I have not sought to repudiate. Yet the variant also encompasses a range of conceptual fields, disciplines, tones, and registers that arguably cannot be contained by the "literary." Inevitably, the variant marks a relation and an interval. For this reason, I'd also propose the variant's non-transcendence. It cannot shake off the attraction of comparison, the reality of adjacency. So, the variant may be of (in the sense of understood as traceable to a certain concept or thing: a normative gender, an item of furniture, even a virus). At the same time, if the variant can provide an opening for feminist inquiry, this has everything to do with its para- status: the fact that what it encompasses is not predetermined, that it contains — indeed, is in some sense defined by — an immanent demand to deliberate.

It would be too easy to conclude that the antiabsorptive poetic styles of Dickinson and Howe exert a demand to stay with difficulty as such. But if (narrating) "the right choice for the right reasons" is what neoliberal society presently stipulates of us, poetics ("And there is also poetry") not only reminds us that we are compelled, but shows us that a different way of relating to people is necessary and possible — though it need not, and arguably cannot, tell us how. This is what Howe's resistance to the law of non-contradiction help us to think. My argument has been that her poetics of the variant contests the production of both poetry and history as institutionally-sanctioned artifacts premised on the repression of non-coincidence: that is, on the repression of what is other. I have also demonstrated that this effort is enmeshed with Howe's critical resistance to the very American tradition of liberal individualism — a tradition that has effectively leveraged the dream of autonomous subjectivity, free from the messiness of relation, into an influential (and contradictory) paradigm for feminist, compositional, and reproductive agency. I offer, finally, that the variant troubles this tradition (and may trouble us) insofar as it pierces this fantasy. Marking the insufficiencies of choosing as a normative discourse for feminism, it especially brings us up against the ideal of a maximally productive feminist subject so often asserted in contemporary political discourse ("breaking the glass ceiling"). As an ethic, then, the variant cannot satisfy us, and yet ethics is exactly what it implicates.

Anna Moser is a writer, researcher, and artist based in West Sussex, UK. Her essays and reviews have been published in both academic and popular forums, including diacritics, Effects, the Verso blog, and The Journal of British and Irish Innovative Poetry. A poetry pamphlet Improbable Furnishings: A Catalogue was published in April 2025 by Earthbound Press. Her first book Held by Form: Feminism, Poetics, Critical Practice will be published by the University of Chicago Press's Thinking Literature series in Fall 2026.

References

- Susan Howe, My Emily Dickinson (New Directions, 1985), 21. [⤒]

- Howe, My Emily Dickinson, 14. See also Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination, with an introduction by Lisa Appignanesi (Yale University Press, 2020). [⤒]

- Howe, My Emily Dickinson, 14. [⤒]

- Howe, My Emily Dickinson, 3. [⤒]

- Howe, My Emily Dickinson, 3. [⤒]

- Fredson Bowers, Textual and Literary Criticism (Cambridge University Press, 1966), 67. [⤒]

- For a synthesis of these debates, see Cristanne Miller, "Controversy in the Study of Emily Dickinson," Literary Imagination: The Review of the Association of Literary Scholars and Critics 6, no. 1 (2004): 39-50. [⤒]

- Susan Howe, "My Emily Dickinson Discussion," moderated by Charles Bernstein, New York Talk, New York, NY, February 24, 1984, 57:50. This dialogue (and all subsequent quotations from the discussion included in this introduction) takes place between approx. 12:00 and 15:00 and can be accessed via the PennSound website. The transcription is my own. [⤒]

- Howe, My Emily Dickinson, 11. [⤒]

- Additionally, the verb "abolish" suggests a belief in poetry's ability to evoke projects of abolition on a societal scale; Howe is aware that, for Dickinson, the word "abolish" would connote political efforts to abolish slavery. [⤒]

- Howe, My Emily Dickinson, 21. [⤒]

- Susan Howe, "The Difficulties Interview," The Difficulties 3, no. 1 (1989), 20. "J 1386" is a reference to Thomas Johnson, The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Including Variant Readings Critically Compared with All Known Manuscripts (Harvard University Press, 1955). [⤒]

- Alexandra Socarides, Dickinson Unbound: Paper, Process, Poetics (Oxford University Press, 2012), 133. [⤒]

- Emily Dickinson, The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition, ed. R.W. Franklin (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1998), 26. Johnson, quoted in Howe, "The Difficulties Interview," 19. [⤒]

- Howe, "The Difficulties Interview," 20. [⤒]

- Susan Howe, "These Flames and Generosities of the Heart: Emily Dickinson and the Illogic of Sumptuary Values," in The Birth-mark: unsettling the wilderness in American literary history (New Directions, 1993), 134. [⤒]

- Howe, "Flames and Generosities," in The Birth-Mark, 134. Franklin uses "the notebooks" here as a simplified term that encompasses the fascicles and the unbound sets. [⤒]

- Dickinson, The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition, ed. R.W. Franklin, 889. I would note that Franklin does call attention to Dickinson's line breaks in a paratext below his transcription of the poem. [⤒]

- Howe, "Flames and Generosities," in The Birth-Mark, 145. [⤒]

- Words taken from Susan Howe, "Pythagorean Silence," in The Europe of Trusts (New Directions, 1990), 82; "The Liberties," in The Europe of Trusts, 207, 208; "Thorow," in Singularities (Wesleyan University Press, 1990); and "Defenestration of Prague," in The Europe of Trusts, 94. [⤒]

- Howe, "Thorow," in Singularities, 48. [⤒]

- Susan Howe, The Midnight (New Directions, 2003), n.p. [⤒]

- Howe, "Bed Hangings I," in The Midnight, 19. [⤒]

- On the idea of Howe's "opacity" as tied to an association in her work "between 'history' and an idea of narrative as a form premised on exclusion and erasure," see Peter Nicholls, "Unsettling the Wilderness: Susan Howe and American History," Contemporary Literature XXXVIII, no. 4 (1996): 586-601 (588). [⤒]

- Howe, "Articulation of Sound Forms in Time," in Singularities, 36. [⤒]

- Charles Bernstein, "Artifice of Absorption," in A Poetics (Harvard University Press, 1992), 18. [⤒]

- Bernstein, "Artifice of Absorption," 9. [⤒]

- Howe, "The Liberties," 149. [⤒]

- Howe, "The Liberties," 152. [⤒]

- Joan Wallach Scott, Gender and the Politics of History: 30th Anniversary Edition (Columbia, 2018), 9. [⤒]

- Scott, Gender and the Politics of History, 30. [⤒]

- Scott, Gender and the Politics of History, 27. [⤒]

- Hannah Arendt, "What is Freedom?," in Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought (Penguin 2006), 151. [⤒]

- Howe, "Articulation of Sound Forms in Time," in Singularities, 22, 26, 33. [⤒]

- Will Montgomery, The Poetry of Susan Howe: History, Theology, Authority (Palgrave MacMillan, 2010), xii. [⤒]

- For a discussion of this see Mandy Bloomfield, Archaeopoetics: Word, Image, History (University of Alabama Press, 2016), 41. [⤒]

- Rachel Blau DuPlessis, "Whowe," in The Pink Guitar: Writing as Feminist Practice (University of Alabama Press, 2006), 135. [⤒]

- Frederic Jameson, Valences of the Dialectic (Verso, 2010), 5. [⤒]

- I am especially referring here to feminism in a late twentieth and twenty-first century Anglophone (primarily Western) context. In the introduction to my forthcoming book Held by Form: Feminism, Poetics, Critical Practice (University of Chicago Press, Fall 2026), I offer a fuller account of this ideal of the feminist subject. [⤒]

- Penelope Deutscher, Foucault's Futures: A Critique of Reproductive Reason (Columbia University Press, 2017), 4; Victoria Browne, Pregnancy Without Birth: A Feminist Philosophy of Miscarriage (Bloomsbury, 2023), 5. [⤒]

- Barbara Johnson, "Apostrophe, Animation, Abortion," Diacritics 16, no. 1 (Spring 1986): 28-47 (33). [⤒]

- Browne, Pregnancy Without Birth, 15-16. [⤒]

- Johnson, "Apostrophe, Animation, Abortion," 33-4. [⤒]

- Johnson, "Apostrophe, Animation, Abortion," 32. [⤒]

- Gwendolyn Brooks, Selected Poems (Harper and Row, 1963), 4. [⤒]

- Johnson, 32. [⤒]

- Johnson, "Apostrophe, Animation, Abortion," 33. [⤒]

- Johnson, "Apostrophe, Animation, Abortion," 33. [⤒]

- Johnson, "Apostrophe, Animation, Abortion," 33. [⤒]

- Johnson, "Apostrophe, Animation, Abortion," 35. [⤒]

- Johnson develops this insight out of her Derridean commitments, interestingly anticipating Derrida's own turn to politics in his 1989 essay "Force of Law." For Derrida, the undecidable is what "opens the field of decision or of decidability." It is thus what engenders the possibility of political responsibility which flows from it. See Jacques Derrida, "Afterword: Toward an Ethic of Discussion," in Limited, Inc. (Northwestern University Press, 1989), 116. For a historicizing discussion of Derrida's politics of undecidability, see David Bates, "Crisis Between the Wars: Derrida and the Origins of Undecidability," Representations 90, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 1-27. [⤒]

- Johnson, "Apostrophe, Animation, Abortion," 32. [⤒]

- Clair Wills, "Quickening, or How to Plot an Abortion," London Review of Books 45, no. 6 (16 March 2023), n.p. [⤒]

- Quoted in Benn Quinn, "England and Wales abortion law has been settled, minister tells Commons," The Guardian, 15 June 2023. [⤒]

- Wills, "Quickening, or How to Plot an Abortion." [⤒]

- Wills, "Quickening, or How to Plot an Abortion." [⤒]

- Wills, "Quickening, or How to Plot an Abortion." In her autobiographical account Happening, Ernaux offers a less passive account of abortion, portraying herself as determinedly seeking to gain access to an abortion in the face of obstacles. At the same time, the narrative retains elements of paralysis: for example, Ernaux describes herself as unable to write her university thesis until the abortion has taken place. Annie Ernaux, Happening, trans. Tanya Leslie (Fitzcarraldo, 2022). [⤒]

- Deutscher, Foucault's Futures, 6. Specifically, Deutscher is addressing what she calls "pseudosovereignty." [⤒]

- Johnson, "Apostrophe, Animation, Abortion," 35. [⤒]

- Jonathan Culler, "Apostrophe," Diacritics 7, no. 4 (Winter 1977): 59-69 (60). [⤒]