Issue 10: The Inaugural Prize Issue

They're a queer episode in the history of this country.

Purely nomadic, and leaving no posterity, for they don't marry.

I'm told they're without any moral sense whatever.—Owen Wister1

[T]he "countryness" is pretty much in my blood.

I'm from Georgia, down south. That voice just lives in me.—Lil Nas X2

As Lil Nas X (Montero Lamar Hill) tells the story, when he first heard the instrumental that would become "Old Town Road," the music transported him to Hollywood's Wild West: "I literally saw myself in a movie, a loner cowboy western. I wanted to run away from everything."3 The singer would later describe his single as "country-trap," a sonic amalgam that found representation on Billboard charts when "Old Town Road" simultaneously ranked on the Billboard Hot 100, Hot Country, and Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs. The feat, however, was short-lived, as genre-blur became boundary misstep. In March 2019, Billboard removed "Old Town Road" from its country charts, asserting that the track lacked necessary elements of the genre, although these elements were never specified.4 Soon after, Lil Nas X released a remix with Billy Ray Cyrus, a 90s pop-country phenomenon well-acquainted with genre-bending scorn. Similarly barred from Hot Country, the remix topped the Hot 100 for a record-setting nineteen weeks.

During this meteoric run, Lil Nas X would reorient the frame through which he and his hit were categorized. On the final day of June 2019 — Pride Month — Lil Nas X tweeted two images from his debut EP's cover with the caption: "deadass thought i [sic] made it obvious."5 The album art accompanying Lil Nas X's Deadass Tweet finds an illustrated Nas atop a horse in a clearing outside a futuristic city. The second image features the same art, zoomed in on a rainbow-lit building. The implication: this rainbow, a nod to Hill's sexuality. In the guise of digital nonchalance, Lil Nas X "came out."

In the aftermath of this Tweet, critics made little connection between "Old Town Road's" country influence and Hill's sexual disclosure. A Guardian profile, for example, proclaimed, "It's perhaps strange that . . . [Lil Nas X] does not explore his sexuality in his music."6 Such commentaries inferred that by not explicitly referencing his sexuality, Lil Nas X avoided queerness in his work — that "Old Town Road" could not be one variation of the expressive life of queerness. Indeed, Lil Nas X says he thought he made it "obvious," which is not to say explicit. He waited two weeks after his EP's release — until the last day of Pride — to draw attention to something ostensibly obvious. Of course, had "it" been so apparent, no tweet would have been needed. Rather, the time between the EP release and Hill's Deadass Tweet reveals what ought to have been obvious, visible, self-evident — yet was not. What, then, was Lil Nas X making obvious? And how else did he make it so?

In this essay, I consider the queer signification of the "loner cowboy" evoked in Lil Nas X's "Old Town Road." I also explore the valences of African American identity encoded in this same mythological cowboy — a connection suggested by "Old Town Road's" "country-trap" styling. In addition to getting kicked off the Billboard Country charts, Lil Nas X elicited scorn due to his country-urban wear. After he signed a sponsorship deal with Wrangler, cries arose that Li Nas X was appropriating cowboy culture. Wrangler's social media was inundated with comments like "cowboy spirit is nothing to be made fun of," and "what a bunch of sell outs . . . keep taking the cowboy outta country."7 I contend that, far from appropriative, Lil Nas X's "Old Town Road" manifests queer and Black traces that persist in the archetypal American cowboy, even as that figure has been redeployed in service of conservative ideologies far removed from minoritarian life.

To demonstrate how white heterosexual culture replicates in the cowboy those queer and Black legacies it aims to disavow, I offer a genealogy of the popular American cowboy. I begin by accounting for the frontier's queer and Black history; then, I explore the contradictory techniques toward that history's erasure in the oft-cited first Western novel, Owen Wister's The Virginian (1902). Next, I consider Shannon Pufahl's queer Western On Swift Horses (2019) and a survey of Western cinema — Red River (1948), Shane (1953), Johnny Guitar (1954), Midnight Cowboy (1969), Buck and the Preacher (1972), The Electric Horseman (1979), Urban Cowboy (1980), Boys Don't Cry (1999) and Brokeback Mountain (2005) — to track the American cowboy's transformation from laborer to racial and gender-signifying mode of being. Finally, I return to "Old Town Road," demonstrating how Lil Nas X announces his queerness through camp-cowboy imagery that makes deadass obvious the cowboy's queer, Black past.

A Regulatory Mythos: Owen Wister's The Virginian

Difference and diversity marked the Wild West from which America's celebrated cowboy emerged. In addition to Native American, Asian, Latinx, and European populations, Black subjects filled the US frontier, although the exact number is a source of historical contestation. Historians Philip Durham and Everett Jones speculate that around five thousand Black cowboys existed between 1860 and 1890.8 Kenneth Wiggins Porter places the number higher, at around nine thousand, or one in every four cowboys.9 Relying on census data, Quintard Taylor estimates far lower, at around two percent; however, as Katherine McKittrick reminds us, the state-sponsored, regulatory nature of such data risks rendering Black geographies as "ostensible impossibilities."10

What is clear is that the frontier ranching industry offered unprecedented labor opportunities for African Americans, including those newly freed on Western land and others, like the Kansas Exodusters, who migrated West. Kenneth Wiggins Porter notes that Black subjects "occupied all the positions among cattle-industry employees," from the "lowly wrangler" to "top hand and lofty cook," although they were rarely "found as ranch or trail boss."11 Porter emphasizes how such cowboys performed their roles "side by side with their white comrades." He argues that while "cow country was no utopia," it saw white and Black populations working together "on more equal terms than had been possible in the United States for two hundred years or would be possible again for nearly another century."12

Historians have likewise retrieved frontier queer subjects from "ostensible impossibilities." Such research sheds light on broader gender transformations unfolding across and beyond the historical moment of the Wild West. In her study of the trial of frontier-era lesbian Alice Mitchell, Lisa Duggan asserts, "The years 1880 to 1920 were a crucible of change in gender and sexual relations in the United States."13 It is during this era that, as Chris Packard puts it, we witness "the modern invention of the 'homosexual' as a social pariah."14 Historian Peter Boag explains, "At the very moment when Americans memorialized the frontier, social understandings of gender and sexuality were undergoing profound alteration, so much so that by the last years of the 1800s, there emerged what historians have termed the 'modern' sexual and gender system."15 Boag's archival work reveals how "sexual perversion" was not a new development but rather newly pathologized; turn of the century sexologists, in characterizing homosexuality as a product of modernity, produced an image of a US frontier free of queerness. When gender variance that did not fit neatly within modern heterosexual parameters found representation within the Western genre, it has typically been rewritten upon non-white bodies — most commonly through largely pejorative Chinese, Mexican, and Native American depictions.16 The mythologized Wild West thus "rendered America's frontier past," as Peter Boag explains, "not only a white place and time, but a heterosexual one as well."17

Scholars have also explored how the Western ranch was itself a space engendered by queer relationality. Western literary and labor historian Blake Allmendinger connects cowboy sociality to the frontier verb to cut — as in, "to castrate" a bull and "to separate" from a herd.18 Just as "castrated steers realized more cash flow . . . single men maximized profits," since unmarried cowboys would work for less money and live in convenient single-sex housing. Cowboys were thus "temporarily and metaphorically castrated in that they were forced to abstain from engaging in relations with women for great lengths of time."19 While Allmendinger's use of "forced" elides the potential for these conditions to be attractive to cow-punchers, his analysis gestures toward the complex gender systems that arose in what Susan Lee Johnson has described as one of the "most demographically male events in human history."20 Johnson considers the traditionally feminine roles cowboys would take on during all-male ranch dances — dynamics generally absent from subsequent frontier reimagining. Likewise, Allmendinger goes so far as to say that Western movies misrepresent "what was really a Felliniesque Mardi Gras" with a "constant reversing and reassigning of sex roles."21 For Johnson, such misrepresentation is part and parcel with the centering of white American experiences in frontier narratives. If, as Johnson puts it, "the Gold Rush benefits from a habit of ritual remembering in mainstream Anglo American culture," then those that do not fit within the parameters of that straight and White-washed mainstream suffer "from an Anglo habit of ritual amnesia."22

To consider the ritualized amnesia that frames the modern cowboy's portraiture, one must unpack the progenitor of the Western novel, Owen Wister's The Virginian (1902). As John Seeyle explains, "What the cowboy was, we can learn from cowboy writers like Andy Adams, but what the cowboy is, in terms of the American popular consciousness, must be credited to Owen Wister."23 The Virginian charts its hero's adventures through an unnamed narrator not unlike Wister himself: an Easterner romantically experiencing the Wild West for the first time. The novel is, perhaps unabashedly, a myth-making document. Wister's own introduction describes the cowboy as belonging to "the historic yesterday," the prospect of seeing him "gallop out of the unchanging silence" as likely as seeing "Columbus on the unchanging sea come sailing."24 The first stories that comprise The Virginian saw print in 1893, the same year Frederick Jackson Turner declared the frontier closed, and with it, the conclusion of the "first period of American history."25 Wister's novel contains, as Aaron Carico puts it, "stage directions for the next act."26

The frontier's "closure" certainly shaped America's economic horizons. The westward expansion onto (stolen) land and the postbellum cessation of "free" labor displaced industrial and agricultural production from the center of the US economic order. In its place, a capitalist-managerial class emerged, one venerated in The Virginian through its eponymous hero.27 Wister's Western performs the ideological work of mapping the rugged and virtuous values of the cowboy onto capitalists, creating what Aaron Carico describes as "a bildungsroman of management."28 The novel charts its hero's transformation from cow-puncher to married ranch middle manager who believes equality is nothing but "a great big bluff."29 By the novel's final paragraph, the Virginian becomes "an important man, with a strong grip on many various enterprises, and able to give his wife all and more than she asked or desired."30 As John Seeyle puts it, "The Virginian is both a noble child of nature and the means by which law-and-order is introduced . . . the agent of the process and its product."31

Crucially, The Virginian conflates law and order, private property, and ruling class interests through a central lynching plot. The turn of the twentieth century saw, in addition to Lisa Duggan's crucible of change in gender and sexual relations, what sociologists Stewart Tolnay and E.M. Beck have described as a "frenzy of lynching." Between 1869 and 1922, an estimated 3,436 lynchings were committed in the U.S., with fewer than a dozen perpetrators receiving any punishment.32 The Virginian reflects the rhetorical efforts made to legitimize lynching in the West. When the Virginian reluctantly hangs a close friend for cattle theft, his future wife, Molly Stark Wood, takes offense. She's convinced otherwise by a judge who characterizes lynching not as "a DEFIANCE of the law . . . [but] an ASSERTION of it — the fundamental assertion of self governing men, upon whom our whole social fabric is based."33 As historian Adam Sowards has argued, the "Western vigilante tradition" relied on a rhetoric that sought to distance Western "posse killings" from Southern lynchings — even though both were "racialized, gendered, brutal and lawless."34

In his study of frontier political economy, Ilia Murtazashvili explains that Western land acquisition rarely occurred via isolated "squatters" but rather organized "claim clubs" that threatened and enacted violence, including lynching, to establish order.35 During his travels West, Owen Wister frequented the Cheyenne Club, an elite Wyoming social club that Christine Bold describes as the "velvet glove" over the "iron fist" of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association (WSGA), a state-wide claim club.36 The WSGA's "vigilante justice" during the Johnson County Wars included the lynching of small ranchers and, in 1892, the arson-murder of small ranchers' association leader Nate Champion — carried out while Owen Wister was staying at the Cheyenne Club. As Christine Bold deftly argues, The Virginian's lynching represents a conflating fictionalization of these WSGA murders. By dramatizing lynching as a remorseful but necessary act committed by the genre's canonical cowboy, Wister turns what was "a brutal murder by a power elite into a democratic uprising" and "an incident of mob violence into an image of heroic individualism."37

In embodying the ideology of cattle barons, Wister's liminal cowboy of the bygone frontier becomes a racialized metaphor for a new capitalist epoch. For Wister, the conquering cowboy was a descendant of the Anglo-Saxon knight-at-arms — a natural aristocrat.38 As Jane Tompkins asserts, he could not come "in a variety of shapes and colors" since, for Wister, his social function "was to ensure that the kinds of people who are in power will remain there."39 The Virginian's lynching thus enacts a broader reconciliation of white elites at the expense of southern Blacks, wherein forms of virulent racism and violence are nationally assimilated under the guise of postbellum reunion. Aaron Carico explores how The Virginian operates as "Owen Wister's meditation on how to renovate white subjectivity, paternalist power, and political authority" during a moment of "profound change."40 For Carico, the first Western is not "western," at all. He writes, "The Virginian's title, and the titular character, and thus the novel itself, are recruiting their energies from a grid of associations tied to 'Southern' slavery."41 Framing the novel as a revisionist mediation uncovers why Wister's protagonist hails from formerly Confederate Virginia, travels with a New England elite, and marries a refined Vermont school teacher. Wister imagines Northern and Southern reconciliation through colonial capitalist oligarchy, one that charts, Carico writes, for "the ex-slave in, ostensibly, an era of freedom . . . no life at all."42

Thus far, I've sought to capture the myth-making drives that animate The Virginian's narrative arc. If Wister's canonical text imbues the Western with such revisionist impulse, so too does it erect a genre foundation built upon contradiction. Jane Tompkins observes that the Western genre's "determination to have a world of absolute dichotomies ensures that interpenetration and transmutation will occur."43 For Tompkins, this dynamic begins with The Virginian, which, she argues, "states so openly the counter-argument to its own point of view."44 One persisting contradiction lies in the homoerotic undertones pervading a novel that resolves in hetero-matrimony. Krista Comer notes that if The Virginian "consolidates the new twentieth-century heterosexual imperative, it also consolidates the struggle against that imperative."45 Such counter-impulses simmer within the text's prose. Owen Wister builds cowboy idealization through his narrator's marked admiration for the Virginian. Idealization, however, quickly blurs, evincing infatuation — or even deadass obvious desire. As Chris Packard highlights in his attentive reading of the text, "The Virginian is the narrator's sometimes-erotic homage to this cowboy, a 400-page love letter."46 The novel opens with our unnamed narrator spotting the Virginian -- "a slim young giant, more beautiful than pictures" -- and apprehending his physique: "undulations of a tiger, smooth and easy, as if all his muscles flowed beneath his skin."47 Before speaking to the Virginian, the narrator daydreams about a life together: "Had I been the bride, I should have taken the giant, dust and all."48

The novel's homoerotic intimations underscore another recurrent tension: the celebration of homosocial connections and derisiveness toward matrimonial bonds. The Virginian's first words come at a newly married man's expense; the hero and narrator later bond over jokes about a hen desperate but unable to lay eggs by herself. In "Hank's Woman," a Wister short story featuring the same characters, the duo skinny-dip while camping. After the narrator notes that "to need no clothes is better than purple and fine linen," the Virginian confesses matrimonial wariness: "Not any such thing as a fam'ly for me, yet. Never, it may be. Not till I can't help it."49 If, as Laura Mulvey has asserted, the classic Western hero is split, one part celebrating "integration into society through marriage" and the other resisting "social standards and responsibilities, above all those of marriage and the family," then this split originates in Owen Wister's eponymous hero.50

The Virginian contains a second, highly charged homosocial bond between the hero and Steve, the close friend he ultimately hangs for alleged cattle theft. Steve is the lone character who calls the protagonist "Jeff," his real name.51 Steve evokes in the Virginian a "deep inward tide of feeling," yet his name was "to the women . . . a name unknown."52 Jane Tompkins explains, "To the women it is a name unknown, since the love adult males feel for one another can receive no outward expression in the society Wister and his characters inhabit." Tompkins even goes so far as to suggest that if times were different, "this could have been a story about 'Jeff' and Steve instead of . . . the Virginian and Molly Stark Wood."53

The possibility of redirected attachment may not have been limited to fiction. Some critics have read Wister's real-life relationship with George West, the Wyoming rancher who inspired the Virginian, as echoing the novel's homosocial tensions. Wister and West during an 1887 Wyoming trip and corresponded frequently for years. After the 1892 murder of Nate Champion during the Johnson County War, Cheyenne Club members convinced Wister it would be unsafe for him, as a supporter of the large cattle kings, to proceed with a planned hunting trip with West. Biographer Darwin Payne notes that it remains a mystery why, instead of writing a letter, Wister traveled some five thousand miles to tell West in person.54 William Handley reads this biographical silence as possible evidence of a same-sex attachment.55 West's penultimate letter to Wister reads: "I want you to remember this, that with all my faults I love you as I did years ago, and shall always want to see you." 56 Yet Wister never named West among the individuals he credited as inspirations for the Virginian, despite having met the others only after inventing the character.57 Like his protagonist, Wister abandoned the frontier and its unstable affections, retreating East to marry and solidify his literary legacy.

As Jane Tompkins asserts, "the Western doesn't have anything to do with the West as such. . . . It is about men's fear of losing their mastery, and hence their identity."58 The Virginian attempts to extinguish two of the biggest threats to that self-mastery: Black life and queer attraction. From its Confederate origins to Steve's lynching, the novel recasts the West as a space for national reconciliation, purged of racial and sexual difference. The Virginian's tensions, however, persist, charting a path for the Western shaped by concealment and contradiction.

Toward Western Wildness: The Cultural Cowboy in Post-War America

A year after The Virginian's publication, the oft-cited first narrative movie was released: The Great Train Robbery (1903).59 Edwin S. Porter's pioneering film established the Wild West's silver screen appeal, as the concluding shot of Justus D. Barnes firing at the camera would become a touchstone for cinematic conventions to come. From cinema's beginnings through the 1960s, approximately a quarter of all American films featured some version of the cowboy.60 Over this time, the cowboy grew estranged not only from his queer and Black history but from another historical legacy: agrarian labor. In the century following the frontier's closing, the cowboy transitions in the popular consciousness from a labor description to a racial and gender-signifying mode of being announced by dress, gesture, and comportment. Rather than a cattle worker, the fabled American cowboy becomes an assemblage of traits — strong, silent, homosocial — paired with iconic visual markers: the ten-gallon hat, buckskin fringe, oversized belt buckle, and high-heeled boots. In other words, one knows the cowboy when one sees him.

Shannon Pufahl captures the mid-century aestheticization of cowboy identification in On Swift Horses (2019), a novel in which thoroughbreds abound yet gallop only on racetracks and silver screens. The year is 1956, and although the frontier has long since "closed," the cowboy still looms large. Children scurry streets with cowboy hats and finger pistols, copying the American Westerns and Mexican Rumberas that fill local cinemas. If turn-of-the-century Americans looked to a frontier past to assuage economic and urbanization anxieties, they returned to the cowboy in the mid-twentieth century as a balm to rabid post-war suburbanization. One On Swift Horses character observes while overlooking the San Diego Valley: "All these cowboys but this whole place will be cul-de-sacs by next year."61 As suburban sprawl threatens to tame every tuft of Western soil, one finds vestiges of the frontier spirit in queer spaces. The novel's Chester Hotel, for example, is an unmarked meeting place for queer men that's often raided by law enforcement. Post-war cosmeticizing of Western land drives the corralling of queer life. A bar patron explains: "They'll clean out the junkies and the queers until the whole thing looks like the Garden of Eden."62

When he isn't looking for love at The Chester, Julius, one of the novel's protagonists, makes a relatively honest living catching cheats at Vegas's Golden Nugget casino. There, he falls for fellow card cheat spotter Henry. During their first romantic moment, the pair encounter a flicker from "the kind of Western they never find to watch, one in which the lens follows not the sheriff or the boy but the dark bandit . . . inside the curtained room where he undresses."63 With his brown skin recast bronze by evening light, Henry, inhabiting Alan Ladd's titular drifter-hero from the film Shane (1953), says, "You go on home, Joey, and grow up to be strong and straight."64 Julius follows the cue: "Shane, come back."65

Henry and Julius recite lines from Shane. They do not alter them. Following Anne Cheng, the cowboy fascination of Henry and Julius could be categorized as a melancholic attraction; despite the Western genre's hostility toward non-White, queer bodies, the cowboy still resonates with these characters.66 I would argue, however, that their shared cowboy enchantment marks something further. Despite the American frontier's heterosexualization, the Western provides phenomenological remnants of queer lives and legacies such that when Henry and Julius engage in playful, romantic foreplay, they may turn to Shane, where the hero's gallant goodbye persists as a queer trace. Following Katherine McKittrick, I contend Henry and Julius use a shared hermeneutics that "feels and questions the unsurvival of the condemned," enabling them to speculate where Alan Ladd's lines may have originated: from the lips of a bronzed cowboy -- perhaps -- just before he embraced the touch of a same-sex lover.67

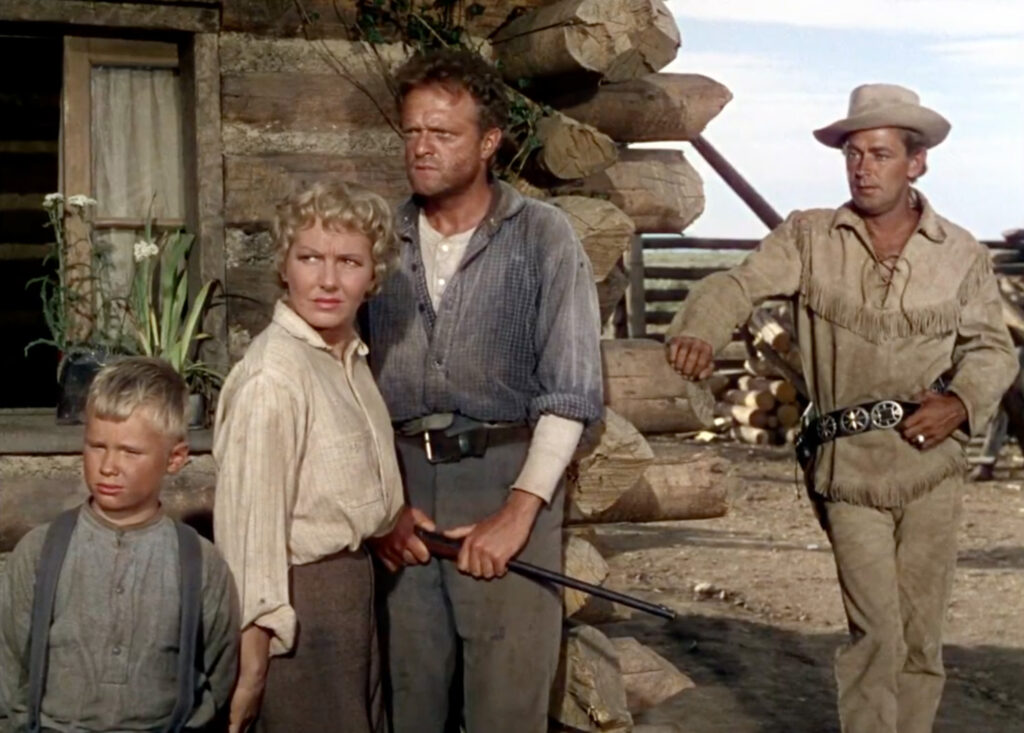

On the surface, Shane is a story of a lone rider who helps homesteaders stay on their land against the threat of hired thugs — a populist rebuttal to The Virginian's pro-cattle king framing of the Johnson County War. The film's first scene establishes a symbolic universe of contrasts. A sweaty, unshaven farmer named Joe (Van Heflin) chops an old tree stump. His son Joey (Brandon De Wilde) alerts his father to a rider's approach. We know Shane (Alan Ladd) is a cowboy by his appearance: clean-shaven and practically aglow in a buckskin fringe that Roger Ebert describes as "a tad precious."68 In his exploration of Shane's shifting reception over five decades, Bob Baker recounts how film critics were first impressed by its documentary-like realism.69 In the wake of "Old Town Road," however, Shane begs a new question: how did the "rugged cowboy" come to wear such preciousness as grit?

As Martin Pumphrey argues, "the masculinities enacted by successive Western heroes . . . [are] made up of many traits that, taken in isolation, would be coded as feminine."70 Such a symbolic universe invariably stimulates the genre's foundational tensions:

In a genre that has always suggested that relationships between men and men are more important (or at least more interesting) than those between men and women, and has always made male friendship and conflict its focus of attention, the process of feminizing the hero to distinguish his masculine toughness from that of the villain(s) has had constantly to negotiate a complexly orchestrated set of homophobic anxieties.71

Shane attempts to negotiate these anxieties through attraction. Young Joey, of course, fixates on the cowboy, but so does his mother, Marian (Jean Arthur). Bob Barker notes that Marian, "like numerous heroines past and still to come," must decide between her husband Joe, the "comfortable endomorph," or "succumb to the temptations presented by . . . Shane, glamourous ectomorph."72 Robin Wood points out that while this is meant to be the dichotomy, "Alan Ladd's insuperable blandness works against it."73 More generally, Barker highlights the technical tensions between depicting Shane as Joey's "chimera" who also must be taken "sufficiently seriously for the relationship with Marian to concern and move us."74 If the family unit, upon Shane's entrance, morphs into a complex digamy, it appears to have less to do with Shane, the man, than Shane, the archetypal cowboy.

The film, of course, resolves neatly. Shane kills the thugs and leaves town, explaining, "There's no living with a killing. . . . Right or wrong, it's a brand, and the brand sticks. There's no going back." Robin Woods argues that Shane's ending comes "as close as possible to reconciling ideological contradiction."75 Wood's formulation, however, captures the tensions that persist. Shane's concluding words recall Blake Allmendinger's link between frontier branding and cowboy castration. While Shane's exit restores the family unit, so too does it highlight the queer presence that has threatened it throughout, generating the sort of questions Roger Ebert's review captures well: "There's something else suggested by [Shane's] behavior, his personality, his whole tone. . . . Why does he present himself as a weakling? Why is he without a woman?"76 Shane gives evidence but provides no answers. Shannon Pufahl, through Julius and Henry, allows one suggestion to rise to the surface, retrieving in Shane's famous farewell to Joey a trace of longing: grow up to be strong and straight, and Joey, take care of them, both of them.77

Shane is by no means singular. Traces of queer life and longing abound in Hollywood's Wild West. Consider Red River (1948), where we find perhaps the most famous instance of the Western's homoerotic subtext rising to the surface.78 While Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman's documentary The Celluloid Closet (1996) memorialized the film's lascivious six-shooter exchange between John Ireland and Montgomery Clift, homosocial themes run throughout.79 The larger narrative finds Matthew Garth (Clift) at odds with adoptive father and self-made capitalist Thomas Dunson (John Wayne). Their feud stages a larger cultural shift in masculinity. If Wayne's stoicism and rigidity once epitomized the cowboy, Clift signified a softer, more contemplative masculinity.80 Their contrast highlights what Steven Cohan frames as America's mid-century masculinity crisis. Cohan points to the 1948 Kinsey report, which empirically revealed the frequency of male homosexual activity, and the homosociality of World War II military service as catalysts in spurring what was termed "The Decline of the American Male."81

By filming Montgomery Clift in soft light — a technique typically reserved for leading ladies — director Howard Hawks throws a phenomenological wrench in habitual Western viewing, rendering Clift an erotic spectacle that blurs distinctions between identification and desire.82 Steven Cohan highlights Matthew's first love scene with Tess Millay (Joanna Dru), wherein Clift faces the camera, talking rapidly as Tess gazes on, reversing Laura Mulvey's cinematic formulation in which women "are simultaneously looked at and displayed" as spectacles for the male gaze.83 Ultimately, Tess is Red River's Molly Wood Stark: peripheral to, yet essential for stabilizing, the film's charged homosocial bond. When Dunson and Garth have their climactic quarrel, Tess shouts, "Anybody with half a mind would know you two love each other!" Tess's outburst gives vivid expression to Anthony Mann's famous dictum: "A woman is always added to the story because without a woman the Western wouldn't work."84 What the woman in the Western makes "work" is masculinity itself, restoring the historically castrated cowboy by attempting to sublimate the genre's homosocial implications. Indeed, by the film's conclusion, Tess looks on "as if she were the best man" when Dunson announces he's made Garth a ranch partner.85 Dunson even updates the ranch brand, adding the first letter of his and Garth's names — a tool of cowboy castration rendered a frontier ampersand.

Building on the queer tensions and compensatory femininities of Shane and Red River, Johnny Guitar (1954) pushes the Western's gender conventions to their performative and parodic limits.86 The film's clean-shaven, eponymous cowboy (Sterling Hayden) is, for Jennifer Peterson, "notably inactive" and demasculinized, from his "ridiculous and flamboyant" moniker to his "feminizing" guitar prop.87 The action instead centers around tavern owner Vienna (Joan Crawford), who is introduced as a castrating presence; her bartender observes to the camera, "I never met a woman who was more man." Vienna wears hardy trousers and elegant gowns, adopting "femininity as easily as masculinity, depending on need."88 Reflecting on Joan Crawford's camp performance, V.F. Perkins likens her stark makeup to a mask, contributing to the film's "unusual overtness of construction."89 Likewise, Peterson compares Vienna's gender play to drag, and, drawing upon Joan Riviere's notion of the masquerade, argues that such play enacts not inauthenticity but "a parodic deconstruction of gender."90

In a gendered reversal of The Virginian's homosocial intimacy, Johnny Guitar plays the proverbial schoolmarm, ancillary to the psychosexual feud between Vienna and Emma (Mercedes McCambridge), the film's primary villain. Emma is supposedly out for Vienna due to romantic jealousy, yet she pays little attention to any male character, appearing outright uncomfortable when forced to dance with her ostensible male crush. Instead, she directs all her energy toward Vienna. For Pamela Robertson, while Emma may embody "stereotypical 1950s images of sick or evil lesbians," McCambridge's campy, over-the-top performance "undermines and critiques the film's misogynistic strategies."91 Emma's queer inflections — and the "kinky eroticism" that defines her feud with Vienna — lay bare the fundamentally queer underpinnings of the homosocial Western writ large.92 As V.F. Perkins argues, "Since [Vienna and Emma] are in evident ways performing the roles usually taken by men, the effect is to bring the erotic subtext of the Western so near the surface as to display them in their intensity and their confusion."93

If mid-century revisionist Westerns made the genre's contradictions visible, films in the following decades amplified them into explicit thematic concerns. Consider how Sidney Poitier's Buck and the Preacher (1972), a dramatization of an African American caravan's escape from White Southerners in pursuit of Western freedom, opens with a striking declaration of historical revisionism: "This picture is dedicated to those men, women, and children who lie in graves as unmarked as their place in history.94 Just as racial history surfaces more overtly, so too do the cowboy's gendered dimensions come into sharper focus. For example, Maggie Günsberg argues that while "masculinity as style and surface . . . was already an ingredient in the American Western," it is in the spaghetti Westerns of the 1960s and 70s that "the external paraphernalia of masculinity . . . acquires extraordinary significance over and in excess of narrative requirements," ultimately inviting readings of masculinity "in terms of masquerade."95

When the cowboy's fastidious aesthetics are spatiotemporally displaced, they may emerge especially specious. In Midnight Cowboy (1969), aspiring prostitute Joe Buck (Jon Voight) heads east to New York, where, in full cowboy attire, he more successfully attracts male clientele.96 Buck forms a homosocial bond with con man Rico "Ratso" Rizzo (Dustin Hoffman), who, after failing to attract female clients for Buck, exclaims, "That great big dumb cowboy crap of yours don't appeal to nobody, except every Jackie on 42nd street! That's faggot stuff!" His cowboy façade attacked, a stammering Joe resorts to Hollywood's past: "John Wayne?! You're gonna tell me that John Wayne's a fag?"

Martin Pumphrey argues that Midnight Cowboy destabilizes cowboy iconography by showing Joe Buck posing in front of a mirror, delighted at the sight of himself under a Stetson brim and tasseled leather. For Pumphrey, the scene communicates the "contradictory instructions about how men should relate to looking and makes clear that critiques which have talked of Westerns offering resolutions to social anxieties are deeply misleading."97 What are these contradictory instructions? Pumphrey explains, "While a particular visual style . . . [is] constantly offered to the spectator as part of an ego ideal, Westerns categorically indicate that for a man openly to display himself . . . is to transgress the discourse of masculinity within which those heroes are constructed."98 Through Joe Buck's self-display, perhaps we see "the kind of Western" On Swift Horses's Henry and Julius never find: inside a curtained room, where a cowboy, having tended to the appearance his role demands but masculinity disavows, gazes at himself with pleasure.

The spectacle of Joe Buck's self-regard — masculinity performing itself too visibly —reveals the fragility of its image-based logic. As Tania Modelski reminds us, such fragility is routinely managed through male power's "cycles of crisis and resolution."99 In the late-1970s, America witnessed a "reassertion of cowboyness," as historian Rebeca Scofield puts it, which was "directly linked to a growing movement to reclaim American masculinity after decades of supposed effeminization."100 Robin Woods likewise argues, "the women's movement of the 60s and 70s produced in Hollywood a backlash of hysterical masculinity."101 A new "hard-line" culture that repudiated the presumed sissification of the 1960s and early 70s returned to the mythologized cowboy as an aspirational, social-political ideal.

In a 1977 interview with journalist Oriana Fallaci, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger attributed his fame to his diplomatic style, which he likened to a "cowboy who rides all alone into the town, the village, with his horse and nothing else."102 The cowboy's political pliability became even more pronounced with the election of the "cowboy president," Ronald Reagan. While the former Hollywood actor sported rhinestone threads and Stetson hats on the campaign trail, discotheques across the U.S. echoed with "Go West," the Village People's queer-innuendo-laced anthem, complete with member Randy Jones playing an eroticized cowboy not unlike Midnight Cowboy's Joe Buck. If Kissinger and Reagan deployed cowboy aesthetics to shore up white, heteronormative nationalism, the Village People mobilized the same iconography to signal queer pleasure.103

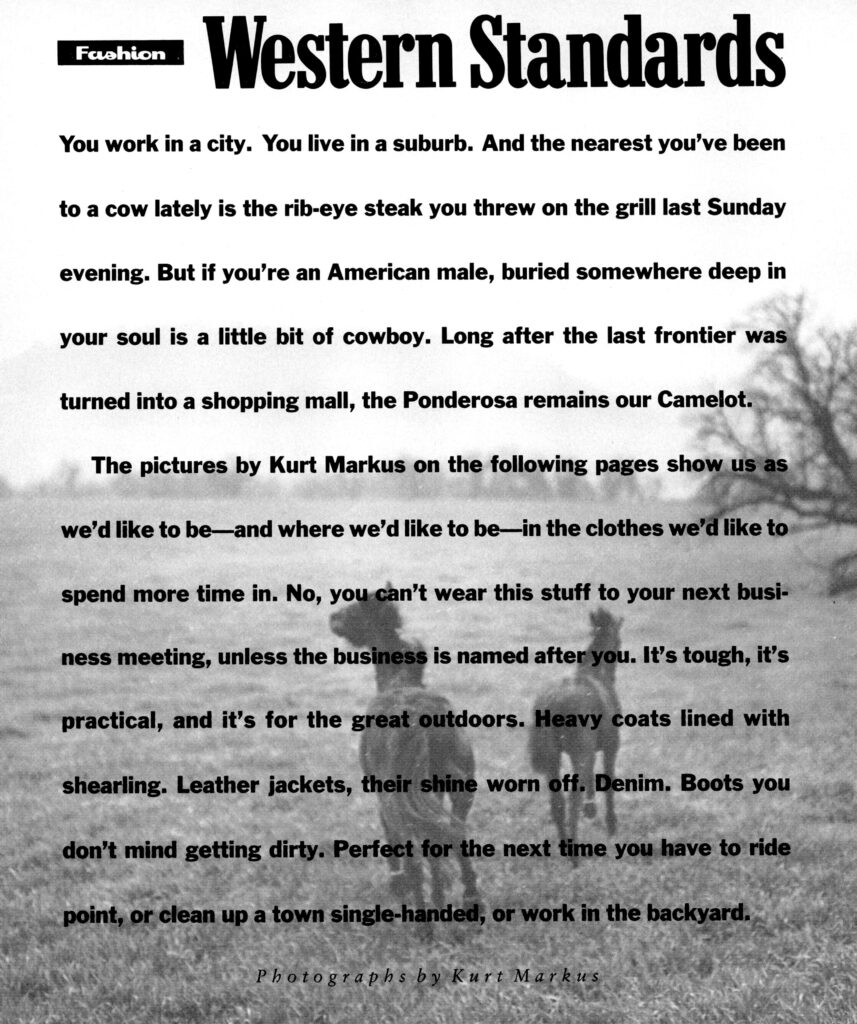

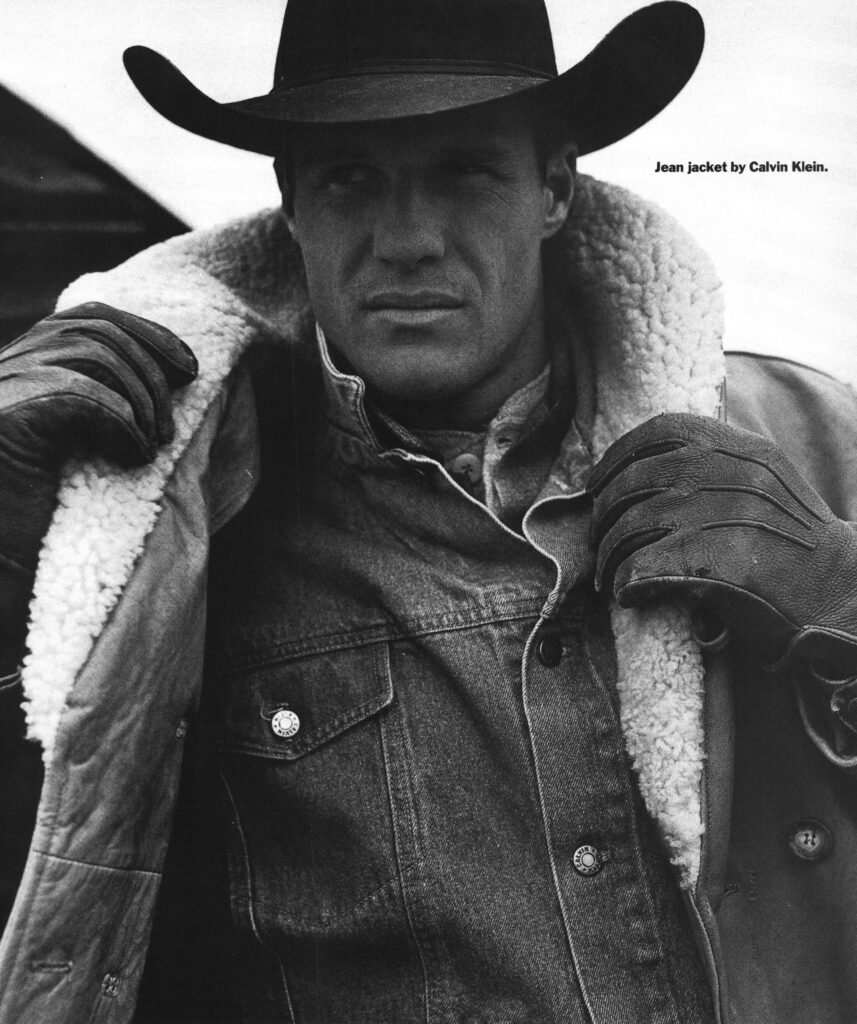

With the cowboy increasingly functioning as a mode of performance — whether on the campaign trail or the dance floor — the Western genre mirrored this shift, relocating its fantasies to new terrains. The Electric Horseman (1979) exemplifies this reorientation, staging the cowboy as a commercial relic rather than a frontier hero.104 Now a decade removed from the Sundance Kid's outlaw trails, Robert Redford stars as Sonny Steele, a once-great rodeo champ who now hawks 'Ranch Breakfast' cereal while appearing in a garish, electrified cowboy suit. If The Electric Horseman satirizes cowboy commodification, Urban Cowboy (1980) embraces it. Here, masculinity unfolds not on the range but at a honky-tonk tucked into Houston's sprawl, where Bud Davis (John Travolta) masters the art of bull riding — that is, mechanical bull riding.105 Urban Cowboy highlights how cowboy aspiration no longer required cattle or open land. By the decade's end, Esquire would introduce a "Western Standards" photography spread by declaring, "You work in a city. You live in a suburb. . . . But if you're an American male, buried somewhere deep in your soul is a little bit of cowboy."106 The cowboy emerged rejuvenated: a myth of apex masculinity rebranded for the suburban closet.

Once severed from the material realities of labor and frontier life, the cowboy figure increasingly indexes gender not as essence but performance — a Butlerian "stylized repetition of acts."107 Kimberly Peirce's Boys Don't Cry (1999) makes legible the cowboy's gendered performativity by revisiting Midnight Cowboy's mirror-bound choreography of masculinity.108 The dramatization of Brandon Teena's life starts with Brandon (Hilary Swank) striking mirror poses — like Joe Buck — while donning a Stetson, cigarette, and blue-jeans packer. Brandon's gay cousin (Matt McGrath) remarks, "Now, if you was a guy, I might even wanna fuck you." Brandon retorts, "You mean if you was a guy, you might even wanna fuck me." As the one with the cowboy hat, Brandon renders biological sex inconsequential to gender expression, albeit at the expense of sexual orientation. In the wake of suburban honky-tonks and Esquire Western wear photoshoots, similarly inconsequential is the location of Brandon's upcoming date: a far-from-the-frontier roller rink. As masculinity's cultural codes dictate, one knows the cowboy when one sees him.109

Despite the cowboy's gender and sexual contradictions, Brokeback Mountain (2005) represented a betrayal.110 Upon the film's release, news articles quoted "real cowboys" who claimed a cowboy couldn't be gay. One ranch worker exclaimed, "They've gone and killed John Wayne with this movie. . . . There ain't no queer in cowboy and I don't care for anyone suggesting there is."111 The film gained a telling sobriquet — "The Gay Cowboy Movie" — that spoke "to the unease surrounding the film's subject."112 When asked about the tagline, Annie Proulx, whose short story inspired the film, highlighted a different colloquial misnomer: her story is not about "cowboys" but "two inarticulate, confused Wyoming ranch kids." Proulx explains, "The only work they find is herding sheep for a summer -- some cowboys! Yet both are beguiled by the cowboy myth, as are most people who live in the state."113 Proulx's ranch kids, however, walk like cowboys, spit like cowboys, wear Stetsons and Wranglers like cowboys — they're even disinterested in their wives like cowboys. It's only by explicitly consummating sexual intimacy that Brokeback's protagonists violate the cowboy's cultural code.

The ornaments of the American cowboy, however, may become queer emblems through a hermeneutical shift. Consider the tune "Cowboys Are Frequently Secretly Fond of Each Other" that Willie Nelson covered for the occasion of Brokeback Mountain's release. According to songwriter Ned Sublette, Nelson proposed the cover for Brokeback Mountain but was turned down "because it was a funny song and they were making a tear-jerking movie. But you know, the song isn't all that funny. It depends on how you do it."114 A playful wink lies behind the title's compound adverbs. Decades of John Wayne and Ronald Reagan masculinity might make the notion of many cowboys secretly, frequently longing for one another an absurdity, rendering the song's second chorus line — Say, what do you think all them saddles and boots was about? — a punchline. Or one may consider the cowboy's saddles and chaps, boot spurs and bandanas, as lived-in artifacts of queer curiosity and longing — perhaps even deadass obvious artifacts.

Lil Nas X: Camp Cowboy as Queer Mythography

If the modern cowboy is a culture industry creation that once told suburbanites they had a "little bit of cowboy" in them, then the memeified rise of "Old Town Road" marks its latest iteration. The song first gained traction via online virality. In the #YeeHawChallenge, TikTok users appeared in everyday clothing, then, upon the bass drop in "Old Down Road," transformed into Western get-ups with exaggerated cowboy dances and mannerisms. The cowboy became what Judith Butler warned us gender was not: "a construction that one puts on, as one puts on clothes in the morning."115

The American cowboy engenders questions of national identity and belonging — who may or may not be a cowboy. Country music is no different. Like Hollywood's Wild West, the genre's Black roots have been obscured. The banjo, a country staple, descends from the West African akonting, its arrival in America a byproduct of forced migration.116 Enslaved Africans, prohibited from playing percussive instruments for fear of coded communication, developed banjo prowess alongside the fiddle and harmonica. While African blues music gave rise to bluegrass and western swing, racialized marketing strategies in the 1920s created a split between Black "race records" and white "hillbilly" music. Following World War II, these genres became, respectively, "rhythm and blues" and "country and Western," although as Historian Tore Olsson explains, "country' has always grown out of a multiracial set of musicians and inspirations."117

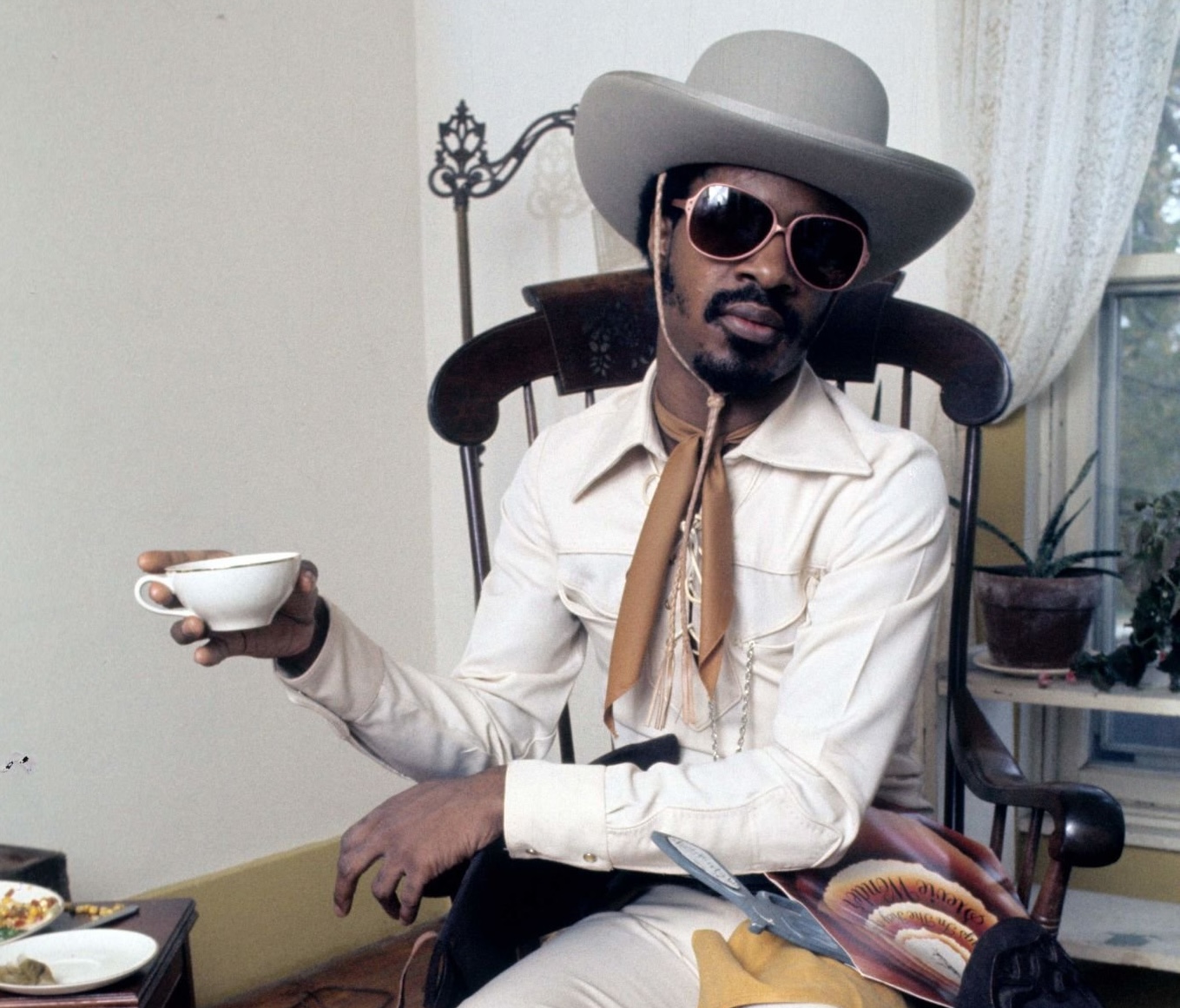

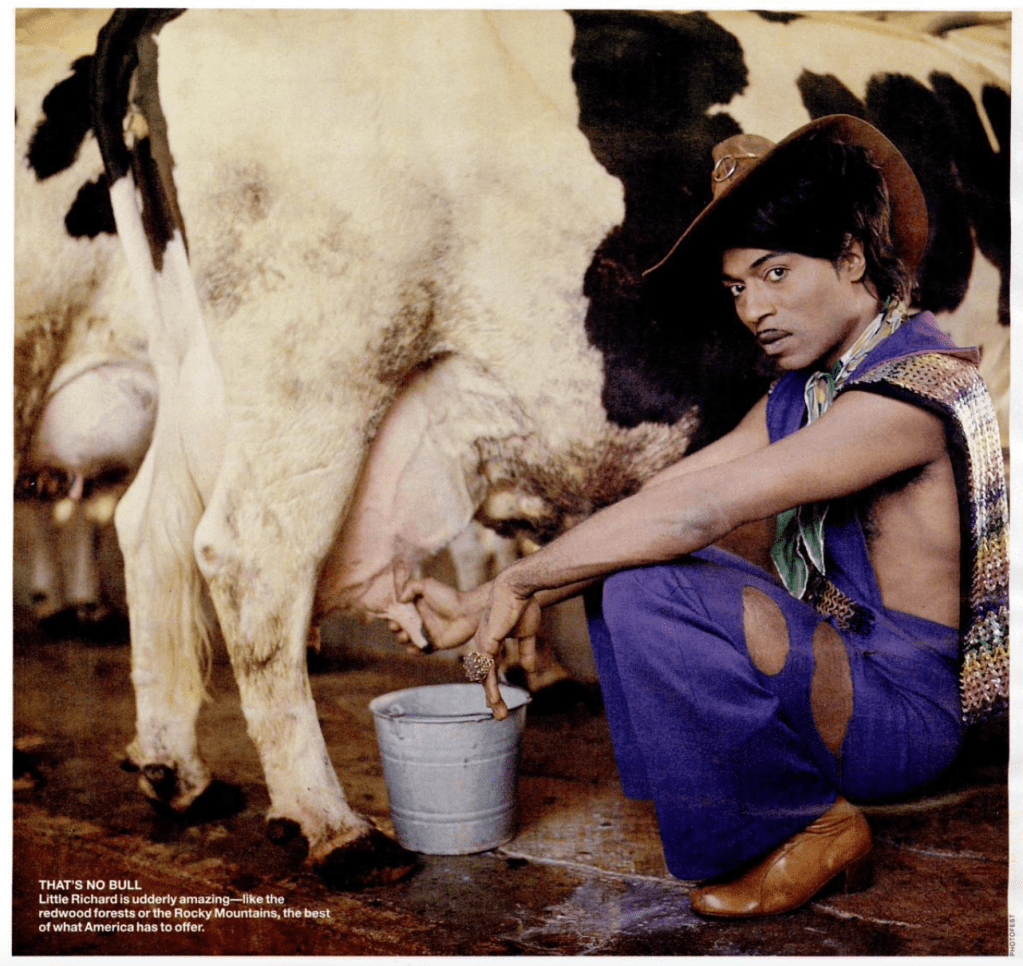

The Black influence on country music persists sonically as well as aesthetically through artists almost entirely relegated from the genre. "Old Town Road" captures a zeitgeist that pop culture archivist Bri Malandro coins the "yee-haw agenda." Malandro chronicles images demonstrating how Black artists have pioneered country style for decades: Stevie Wonder wearing a bolo, Little Richard milking a cow, Beyoncé vacationing in a Stetson, Megan Thee Stallion rocking rhinestone chaps, Lil Kim most days of the week.118 The catalog goes on, Malandro's work evincing the impossibility of exhaustive listing.

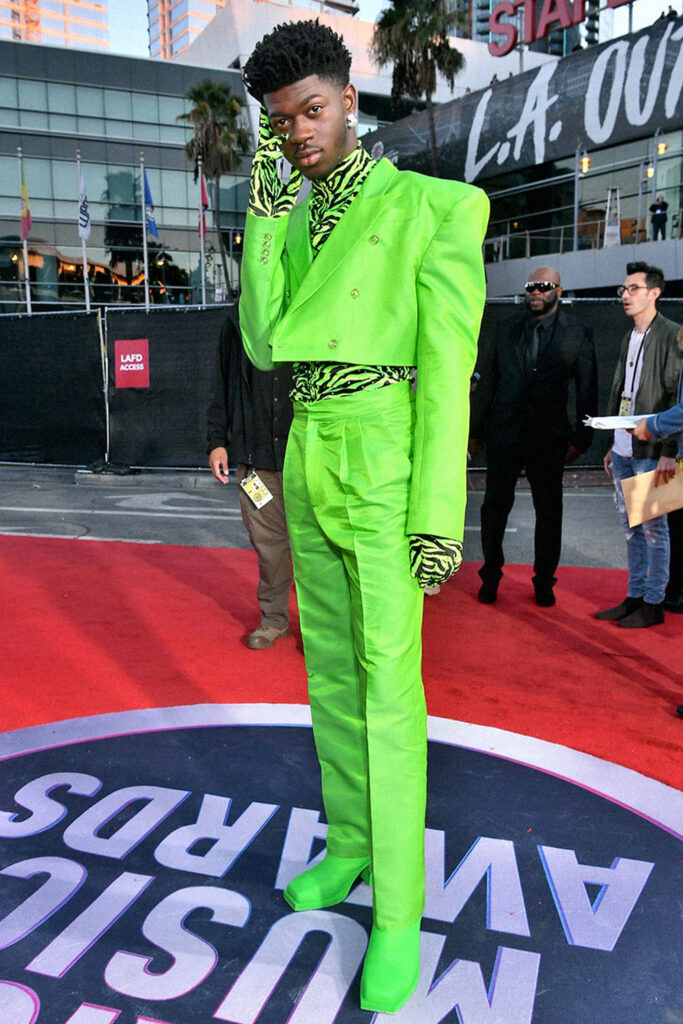

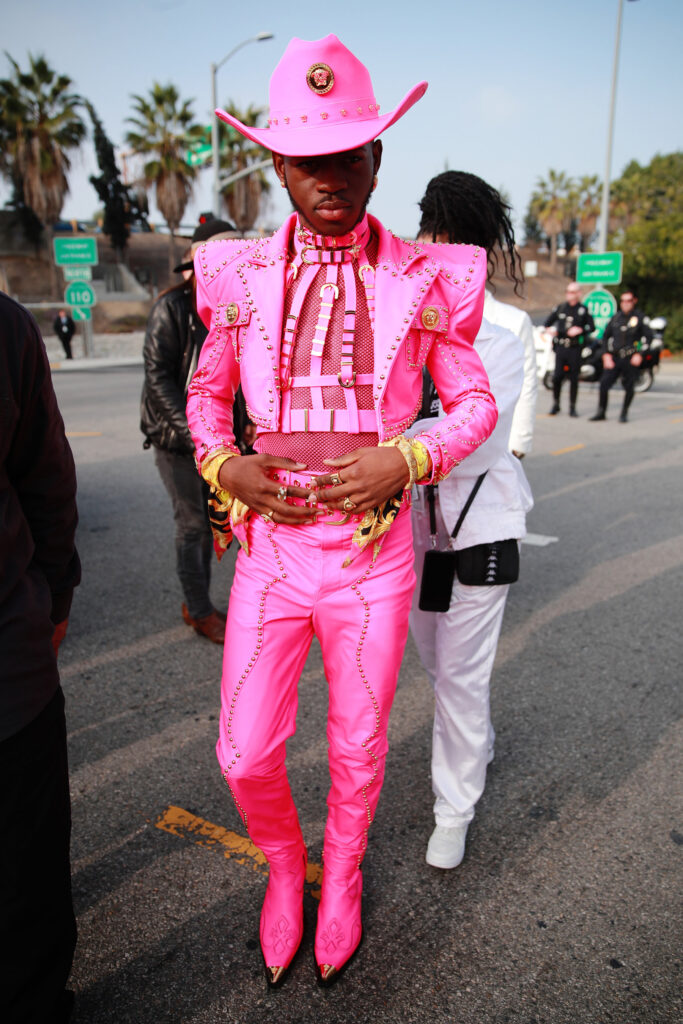

Notably, whereas Malandro's archive features many Black artists casually wearing country garments, there was nothing quotidian about Lil Nas X's Western wear. In the "Old Town Road" music video, Lil Nas X sports a black suit adorned with bedazzled roses, a rhinestone bolo tie, long leather tassels, and drooping earrings.119 Suit designer Joe David Walters notes the glam aspirations: "These suits were originally made for people riding in big events like the Rose Parade. They had to really stand out and shine so that the people way in the back would take notice."120 Indeed, the bedazzled Nudie suitis fit for a stage — not the frontier — and places Lil Nas X in a lineage that includes mainstream country showmen like George Jones and Lefty Frizzell, "outlaw country" stars like Waylon Jennings and Hank Williams, queer and Black iconoclasts like Elton John and Bootsy Collins, and "cowboy president" Ronald Reagan. Following the chart-rising success of "Old Town Road," Lil Nas X offered a sustained array of designer looks that, while influenced by cowboy portraiture, were fundamentally divorced from ranch life. These outfits included a Gucci snakeskin suit with pastel-pink lapels and pussy-bow blouse, a chartreuse Christopher John Rogers suit with a cropped blazer and zebra-print shirt and gloves, and a pink Versace suit with gold studs, BDSM-inspired harness, mesh undershirt, and twin gold bandanas around each wrist.121 It was Lil Nas X who performed the ultimate #YeeHawChallenge, transforming into a camp-cowboy superstar.

To capture the cultural interjection engendered by Lil Nas X's camp cowboy, consider Sylvia Wynter's theorizing the unsettling of colonial power: "The true leap . . . consists in introducing invention into existence. The buck stops with us."122 Wynter cites Frantz Fanon's call for invention to counteract the colonial violence that renders Black life as awaiting erasure from a "history that others have compiled."123 C. Riley Snorton takes up Wynter and Fanon's call in his histography of Black trans life. To account for lives never intended to survive colonial violence, Snorton asserts, "requires nothing short of invention, which is to say . . . a narrative composed from fiction, as fiction, and as fiction as 'facts.'"124

Whereas Snorton's work efforts to retrieve — which is also to say "invent" — lives lost that were never meant to survive, the "Old Town Road" music video engages in a similar act, albeit one of self-creation. The video begins in 1889 with Nas on the run. He jumps down a rabbit hole and lands in inner-city Los Angeles circa 2019. He rides through the city on horseback while kids and adults alike look on, dumbfounded. After Lil Nas X trades in brown-beige breeches for a bedazzled Nudie suit, the video's modern world warms to him; only in his glitzy getup is he legible as cowboy. "Lil Nas X the trap-country cowboy" is a resulting enmeshment of cultural memory and personal creation — a mythographic act in the tradition of Audre Lorde.125 Snorton captures Lorde's biomythography as "a praxis of invention that erupts as a question about (past and present) temporalities in the register of the future imperfect."126 Whereas Lorde "wields memoir as the corrective," Lil Nas X commands the American cowboy, tethering self-creation and historical reclamation.127

Crucially, in the "Old Town Road" music video, Lil Nas X is not alone: his cowboy transformation occurs alongside Billy Ray Cyrus.128 As a pair, they mirror the homosocial bonds that constitute canonic Westerns, from The Virginian and Red River to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), the ending of which provides, for Cynthia Fuchs, the "image of disastrous ejaculatory excess" emblematic of cinematic male bonds.129 For Fuchs, the Western's homosocial bond gives rise to the modern buddy film, in which "the secrecy of masculine intimacy and vulnerability is sustained . . . by the 'marriage' of racial others, such that the transgressiveness of black-white difference displaces homosexual anxiety."130 Riding a Maserati and twirling in fringe, Lil Nas X and Billy Ray evoke both the Western and biracial buddy duo, channeling century-spanning homosocial anxieties that ought to have been obvious.

With his mythographic creation, Lil Nas X does not attempt to prove any history of queer or Black cowboys; instead, through camp excess, he disregards an inherited frontier representationalist order that enshrines the cowboy as white and straight. Upon the canvas of the mythological cowboy, Lil Nas X enacts what theorist Tavia Nyong'o terms "afro-fabulation." For Nyong'o, "The afro-fabulation of black art and performance corrects the representationalist and periodizing terms of our aesthetico-political order. It does so not by representing what is the case . . . but by presenting the falsification of this 'true' order as a pathway toward its correction."131 Counter-mythologies, he argues, may operate as a form of counter-memory that combat the "empowered fictions" of colonial states. He explains: "I write at a time when the powers of the false are needed more than ever, precisely in order to refuse the terms by which present cultural politics are increasingly being reordered to suit the dictates of a bullying and belligerent white nationalism."132 It follows that the timing of Lil Nas X's emergence during Donald Trump's first presidency is no coincidence. Just as Ronald Reagan's cowboy presidency took shape while the Village People were queering cowboy iconography on disco dance floors, Lil Nas X's rise tracks alongside Trump's co-optation of those same queer cowboy aesthetics. That "Old Town Road" became a viral sensation while Trump danced to "Macho Man" and "YMCA" at his rallies only underscores the cowboy's legacy of fabulation and contradiction.

In an era when reparative claims can be dismissed as "fake news," the falsified gimmick becomes a mode of disruption. Lil Nas X, in other words, invented himself by and against an inherited representationalist order, revealing fictions therein. His campified cowboy encourages cries of fraudulence — the same identarian-policing that has barred Black and queer individuals from the parameters of "country" since the frontier's closing. By crying fraud at "Old Town Road" — which is to say, crying fraud at queer or Black cowboys — one merely reanimates the inauthenticity that has long shaped the cowboy's popular portraiture.

Coda: On Frontiers Present and Future

In the "Old Town Road" music video, after a horse-riding Lil Nas X defeats a sports car in a drag race, his opponent asks, "I've seen you before. You're from Compton, right?" Fresh from 1889, Lil Nas X doesn't understand the comment. Compton, however, is home to the Compton Cowboys, one of many inner-city ranches in America that connects its members to "the rich legacy of black cowboys in American culture."133 Following the murder of George Floyd, the Compton Cowboys took to the streets, transforming the fantastical vision of Lil Nas X riding through modern LA on horseback into a very real image of civic unrest.

Like the Compton Cowboys, Lil Nas X's camp cowboy enacts reclamation, albeit by harnessing the mythologized cowboy's spirit of anomalous self-narrativization to bring historical contestations into the tenor of futurity. The American West has always been a product of embellishment and fabrication, exceeding itself almost immediately upon its closure. These aggrandizements are not incidental but essential elements of U.S. identity that have served socio-political ends far longer than the frontier's "actual" existence. If The Virginian proliferated a frontier in service of a white, heteronormative, capitalist imperative — while simultaneously consolidating impulses against it — Lil Nas X channels those enduring oppositional energies. His camp cowboy excavates traces embedded in the West's cultural legacy, reframing the cowboy not as a fixed icon but a mutable archetype, constituted by the queer and Black traces that shaped him all along. After "Old Town Road," may those traces remain deadass obvious.

Michael James Harrington is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at New York University's College of Arts and Sciences. His manuscript-in-progress, Always Been Queer: Retracing Masculinity, excavates queer legacies embedded within visual, literary, and cultural performances of cis-masculinity. He holds a Ph.D. in English from Princeton University and a B.A. in English and Sociology from Amherst College. Michael is a Pushcart-nominated poet, board member of the Accountability Journalism Institute, and recipient of NYU's 2024-2026 Provost's Postdoctoral Fellowship.

References

- Owen Wister, Owen Wister Out West: His Journals and Letters, ed. Fanny Kemble Wister (The University of Chicago Press, 1968), 39. [⤒]

- Jack Mills, "The Story of Lil Nas X, a Country-Trap Cowboy Born Online," Dazed, July 30, 2019; Lil Nas X, "Old Town Road," track 8 on 7 EP, Columbia Records, 2019. [⤒]

- Mills, "The Story of Lil Nas X." [⤒]

- For more, see Brendan Klinkenberg, "Billboard May Revisit Decision to Remove 'Old Town Road' from Country Chart," Rolling Stone, April 6, 2019. [⤒]

- Lil Nas X, Twitter Post, June 30, 2019. [⤒]

- André Wheeler, "Lil Nas X: 'I 100% Want to Represent the LGBT Community,'" The Guardian, April 4, 2020. [⤒]

- Quoted in Cydney Henderson, "Wrangler's Lil Nas X 'Old Town Road' Collection Slammed as Cowboy 'Cultural Appropriation,'" USA Today, May 24, 2019. [⤒]

- Philip Durham and Everett L. Jones, The Negro Cowboys (University of Nebraska Press, 1965), 12. [⤒]

- Kenneth Wiggins Porter, The Negro on the American Frontier (Arno Press, 1971), 373-374. [⤒]

- Quintard Taylor, In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990 (W. W. Norton & Company, 1999), 157-158; Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (University of Minnesota Press, 2006), 5. [⤒]

- Kenneth Wiggins Porter, "Negro Labor in the Western Cattle Industry, 1866-1900," Labor History 10, no. 3 (June 1969): 346-74, 348. [⤒]

- Porter, The Negro on the American Frontier, 367. [⤒]

- Lisa Duggan, "The Trials of Alice Mitchell: Sensationalism, Sexology, and the Lesbian Subject in Turn-of-the-Century America," Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 18, no. 4 (1993): 791-814, 791; for more on "homosexuality" in this era, see John D'Emilio and Estelle B. Freedman, "Toward a New Sexual Order, 1880-1930," in Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America (Harper & Row, 1988), 171-235. [⤒]

- Chris Packard, Queer Cowboys: And Other Erotic Male Friendships in Nineteenth-Century American Literature (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 3. [⤒]

- Peter Boag, Re-Dressing America's Frontier Past (University of California Press, 2012); also see: Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction (Vintage, 1990). [⤒]

- Boag, Re-Dressing, 130-158. [⤒]

- Boag, Re-Dressing, 7. [⤒]

- Blake Allmendinger, The Cowboy: Representations of Labor in an American Work Culture (Oxford University Press, 2023), 51. [⤒]

- Allmendinger, The Cowboy, 6. [⤒]

- Susan Lee Johnson, Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Rush (W.W. Norton, 2001), 12. [⤒]

- Allmendinger, The Cowboy, 55. [⤒]

- Johnson, Roaring Camp, 51. [⤒]

- John Seelye, "Introduction," in The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains (Penguin, 1988), ix. [⤒]

- Owen Wister, The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains (Macmillan, 1902), xiii. [⤒]

- Frederick J. Turner, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History," Annual Report of the American Historical Association for the Year 1893, (Government Printing Office, 1894). [⤒]

- Aaron Carico, Black Market: The Slave's Value in National Culture after 1865 (The University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 112-113. [⤒]

- Gilded-era economic sense dictates why, fewer than two decades after all citizens were granted equal protection under the law, Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad Company (1886) granted those same equal rights to corporations. [⤒]

- Carico, Black Market, 115. [⤒]

- Wister, The Virginian, 144. Moreover, the narrator soon after says, "true democracy and true aristocracy are one and the same thing." See: Wister, The Virginian, 147. [⤒]

- Wister, The Virginian, 506. [⤒]

- Seelye, "Introduction," xiii. [⤒]

- Stewart Emory Tolnay and E. M. Beck, A Festival of Violence: An Analysis of Southern Lynchings, 1882-1930 (University of Illinois Press, 1995), 3. [⤒]

- Wister, The Virginian, 436. [⤒]

- Adam M. Sowards, "Reckoning with History: The Legacy of Lynching in the West," High Country News, January 24, 2024. [⤒]

- Ilia Murtazashvili, The Political Economy of the American Frontier (Cambridge University Press, 2016). [⤒]

- Christine Bold, The Frontier Club: Popular Westerns and Cultural Power, 1880-1924 (Oxford University Press, 2013), 4. [⤒]

- Bold, The Frontier Club, 1. [⤒]

- See Owen Wister, "The Evolution of the Cow-Puncher," Harper's Magazine, 1895. [⤒]

- Jane Tompkins, West of Everything: The Inner Life of Westerns (Oxford University Press, 2006), 148. [⤒]

- Carico, Black Market, 136. [⤒]

- Carico, Black Market, 106. [⤒]

- Carico, Black Market, 136. [⤒]

- Tompkins, West of Everything, 48. [⤒]

- Tompkins, West of Everything, 155. [⤒]

- Krista Comer, "Literature, Gender, and the New Western History," in The New Western History: The Territory Ahead, ed. Forrest G. Robinson, (University of Arizona Press, 1997), 99-134, 112. [⤒]

- Packard, Queer Cowboys, 44. [⤒]

- Wister, The Virginian, 2. [⤒]

- Wister, The Virginian, 4. [⤒]

- Owen Wister, "Hank's Woman" in The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains (Penguin, 1988), 328-9. [⤒]

- Laura Mulvey, "Afterthoughts... Inspired by Duel in the Sun," Framework, no. 15 (1981): 12-15, 14. [⤒]

- Wister, The Virginian, 423-4. [⤒]

- Wister, The Virginian, 339. [⤒]

- Tompkins, West of Everything, 150. [⤒]

- Darwin Payne, Owen Wister: Chronicler of the West, Gentleman of the East (Bison, 2011), 89. [⤒]

- William R. Handley, Marriage, Violence and the Nation in the American Literary West (Cambridge University Press, 2002), 79-83. [⤒]

- Quoted in Handley, Marriage, Violence and the Nation, 82. [⤒]

- Payne, Owen Wister, 94-95. [⤒]

- Tompkins, West of Everything, 17. [⤒]

- The Great Train Robbery, directed by Edwin S. Porter (Edison Studios, 1903). [⤒]

- Stuart Miller, "'The American Epic': Hollywood's Enduring Love for the Western," The Guardian, October 21, 2016. [⤒]

- Shannon Pufahl, On Swift Horses (Riverhead Books, 2019), 203. [⤒]

- Pufahl, On Swift Horses, 185. [⤒]

- Pufahl, On Swift Horses, 93. [⤒]

- Shane, directed by George Stevens (Paramount Pictures, 1953). [⤒]

- Pufahl, On Swift Horses, 93. [⤒]

- Anne Anlin Cheng, The Melancholy of Race: Psychoanalysis, Assimilation and Hidden Grief (Oxford University Press, 2001). [⤒]

- Katherine McKittrick, "Axis, Bold as Love: On Sylvia Wynter, Jimi Hendrix, and the Promise of Science," in Sylvia Wynter. on Being Human as Praxis (Duke University Press, 2015), 156. [⤒]

- Roger Ebert, "Shane Movie Review & Film Summary (1953)," RogerEbert.com, September 3, 2000. [⤒]

- Bob Barker, "Shane Through Five Decades," in The Book of Westerns, ed. Ian Cameron and Douglas Pye (Continuum, 1996), 214-20, 215. [⤒]

- Martin Pumphrey, "Why Do Cowboys Wear Hats in the Bath?: Style Politics for the Older Man," in The Book of Westerns, ed. Ian Cameron and Douglas Pye (Continuum, 1996), 50-62, 56. [⤒]

- Pumphrey, "Why Do Cowboys," 53. [⤒]

- Barker, "Shane," 216. [⤒]

- Robin Wood, "Duel in the Sun," in The Book of Westerns, ed. Ian Cameron and Douglas Pye (Continuum, 1996), 189-95, 191. [⤒]

- Barker, "Shane," 216. [⤒]

- Wood, "Duel," 191. [⤒]

- Ebert, "Shane Movie Review." [⤒]

- On Swift Horses's plot mirrors Shane's love triangle: the wife of a land-settling husband finds herself attracted to a more rugged wrangler. Whereas Marion's attraction to Shane appears like mysterious providence, Pufahl unties the knot by introducing gender into the equation, as the novel's housewife falls in love with another woman. [⤒]

- Red River, directed by Howard Hawks (Monterey Productions, 1948). [⤒]

- Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, dirs., The Celluloid Closet (Channel Four Films, 1996). [⤒]

- Deborah Thomas, "John Wayne's Body," in The Book of Westerns, ed. Ian Cameron and Douglas Pye (Continuum, 1996), 75-87; for more on Wayne's masculine gender performativity, including his hatred of horses, see Gary Wills, John Wayne's America (Simon & Schuster, 1998). [⤒]

- Quoted in Steven Cohan, Masked Men: Masculinity and the Movies in the Fifties (Indiana University Press, 1997), xi. [⤒]

- Clift was also, we now know, gay; his legacy provides a testament to the many queer artists that shaped the ostensibly hyper-masculine and hyper-straight Hollywood cowboy. [⤒]

- Laura Mulvey, "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema," Screen 16, no. 3 (1975): 6-18, 13. [⤒]

- Quoted in Pam Cook, "Women and the Western," in The Western Reader, ed. Jim Kitses and Gregg Rickman, 293-300, 293. [⤒]

- Joan Mellen, Big Bad Wolves: Masculinity in the American Film (Pantheon, 1977), 179. [⤒]

- Johnny Guitar, directed by Nicholas Ray (Republic Pictures, 1954). [⤒]

- Jennifer Peterson, "The Competing Tunes of 'Johnny Guitar': Liberalism, Sexuality, Masquerade," Cinema Journal 35, no. 3 (1996): 3-18, 13. [⤒]

- Leo Charney, "Historical Excess: Johnny Guitar's Containment," Cinema Journal 25.4, (1990): 23-34, 30. [⤒]

- V.F. Perkins, "Johnny Guitar," in The Book of Westerns, ed. Ian Cameron and Douglas Pye (Continuum, 1996), 221-9, 225. [⤒]

- Peterson, "The Competing Tunes," 12-3. [⤒]

- Pamela Robertson, "Camping Under Western Stars: Joan Crawford in Johnny Guitar," Journal of Film and Video 47, (1995): 33-49, 46, 33. [⤒]

- Robertson, "Camping Under Western Stars," 40. [⤒]

- Perkins, "Johnny Guitar," 228. [⤒]

- Buck and the Preacher, directed by Sidney Poitier (Columbia, 1972). [⤒]

- Maggie Günsberg, Italian Cinema: Gender and Genre (Palgrave, 2005), 182. [⤒]

- Midnight Cowboy, directed by John Schlesinger (United Artists, 1969). [⤒]

- Pumphrey, "Why Do Cowboys," 56. [⤒]

- Pumphrey, "Why Do Cowboys," 56. [⤒]

- Tania Modleski, Feminism Without Women: Culture and Criticism in a "Postfeminist" Age (Routledge, 1991), 7. [⤒]

- Rebecca Scofield, "Riding Bareback: Rodeo Communities and the Construction of American Gender, Sexuality, and Race in the Twentieth Century" (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2015), 110. [⤒]

- Robin Wood, Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan...and Beyond (Columbia University Press, 2012), 110. [⤒]

- Oriana Fallaci, Interview with History (Houghton Mifflin, 1977). [⤒]

- This tension continues into the present, as the Village People's music — and eventually the group itself — have featured at Donald Trump's political rallies, a striking absorption of disco-era queer camp into right-wing performance. [⤒]

- The Electric Horseman, directed by Sydney Pollack (Columbia Pictures, 1979). [⤒]

- Urban Cowboy, directed by James Bridges (Paramount Pictures, 1980). [⤒]

- "Western Standards," Esquire, September 1989; quoted in Scofield, "Riding Bareback," 110. [⤒]

- Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York: Routledge, 1999), 179. [⤒]

- Boys Don't Cry, directed by Kimberly Peirce (Searchlight, 1999). [⤒]

- It is worth considering Jack Halberstam's reading of Boys Don't Cry's climax, in which Brandon Teena becomes "a figure who combines momentarily the activity of looking with the passivity of the spectacle." I would add that Kimberly Peirce subverts Laura Mulvey's gendered gaze by introducing the film's protagonist as transgender subject and cowboy. See Jack Halberstam, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (New York University Press, 2005), 88. [⤒]

- Brokeback Mountain, directed by Ang Lee (Paramount, 2005). [⤒]

- Quoted in Phillip Sherwell, "'John Wayne Made Real Movies. There Ain't No Queer in Cowboy,'" The Telegraph, January 1, 2006. [⤒]

- Manohla Dargis, "'Brokeback' and the Gay Frontier," The New York Times, December 20, 2005. [⤒]

- Quoted in Matthew Testa, "Exclusive PJH Interview: At Close Range with Annie Proulx," Planet Jackson Hole, December 5, 2005. [⤒]

- Quoted in Graham Reid, "Willie Nelson: Cowboys Are Frequently Secretly Fond of Each Other (2006)," Elsewhere by Graham Reid, August 14, 2017. [⤒]

- Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex (Taylor and Francis, 1996), 226. [⤒]

- Quoted in Greg Allen, "The Banjo's Roots, Reconsidered," NPR, August 23, 2011. [⤒]

- Quoted in Mills, "The Story of Lil Nas X." [⤒]

- Bri Malandro, "The Yee-Haw Agenda," Instagram. [⤒]

- Lil Nas X, "Old Town Road," directed by Calmatic, May 17, 2019, Music Video. [⤒]

- Erica Euse, "How Lil Nas X's Iconic Suit in the 'Old Town Road' Video Came Together," i-D, May 17, 2019. [⤒]

- Lil Nas X's pink Versace outfit particularly highlights parallels between queer and country aesthetics. His leather harness, for example, evokes both the queer leather community and the cattle industry. Additionally, Lil Nas X's twin bandanas provide a nod to flagging, the queer subcultural practice of using bandanas to communicate one's sexual interests non-verbally. Flagging can be traced to frontier mining camps; due to the shortage of women, men used bandanas to communicate if they wished to "lead" or "follow" during male-dominated square dances. Queer communities later turned to this everyday frontier item, with color coding becoming standardized in Bob Damron's Address Book. For more, see Alexander Kacala, "The Handkerchief Code, According to 'Bob Damron's Address Book' in 1980," The Saint Foundation, April 25, 2019. [⤒]

- Sylvia Wynter, "Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, after Man, Its Overrepresentation--an Argument," CR: The New Centennial Review 3, no. 3 (2003): 257-337. [⤒]

- Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Mask, trans. Charles Lan Markmann (Grove Press, 1967), 120. [⤒]

- C. Riley Snorton, Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 183. Here Snorton is talking specifically of Phillip DeVine, the Black, disabled teen who was murdered alongside Brandon Teena and erased from the film Boys Don't Cry. Snorton "invents" DeVine as a "usable history" for Black and trans lives. Relatedly, in her Gold Rush histography, Susan Lee Johnson describes her practice as one of "reinventing." See Johnson, Gold Rush, 51. [⤒]

- Audre Lorde, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (Crossing Press, 1982). [⤒]

- Snorton, Black on Both Sides, 184. [⤒]

- Faith Adiele, Family Trouble: Memoirists on the Hazards and Rewards of Revealing Family (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), 78. [⤒]

- Billy Ray Cyrus's appearance at Donald Trump's 2025 inaugural "Liberty Ball" underscores his current alignment with conservative politics — a disjuncture that heightens the irony of his pairing with Lil Nas X. Their collaboration reflects the Western's inherent instability, where queerness and nationalist nostalgia may uneasily coexist beneath frontier myth. [⤒]

- Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, directed by George Roy Hill (Twentieth Century Fox, 1969); Cynthia Fuchs, "The Buddy Politic," in Screening the Male: Exploring Masculinities in Hollywood Cinema, eds. Steven Cohan and Ina Rae Hark, (Routledge, 1993), 194-12, 195. [⤒]

- Fuchs, "The Buddy Politic," 203. [⤒]

- Tavia Nyong'o, Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life (NYU Press, 2019), 19. [⤒]

- Nyong'o, Afro-Fabulations, 43. [⤒]

- Walter Thompson-Hernández, The Compton Cowboys: The New Generation of Cowboys in America's Urban Heartland (William Morrow, 2021). [⤒]