Cultural Analytics Now

Katherine Bode, A World of Fiction

1: Remember when we used to fight about corpora?

I read Katherine Bode's "The Equivalence of Close and Distant Reading; Or, toward a New Object for Data-Rich Literary History" in preprint, circulated just prior to its March 2017 publication in Modern Language Quarterly. Though it struck me as fearsome at the time, the debate that erupted now seems quaint. I was a graduate student, and this was one of the first scholarly debates I witnessed unfolding in realtime. Social media's utility in fostering debate was still novel (to me, at least). The fire emoji was not yet ubiquitous, but the debate was ![]() nonetheless.

nonetheless.

Bode articulated a long-standing critique of large-scale text analysis methods: a neglect of book history. Franco Moretti and Matthew Jockers (Bode's targets) use large datasets that they claim represent the historical record objectively, but are, in fact, skewed by limitations. Because they ignore the bibliographic and editorial record — the conditions under which texts were not only produced, but circulated, received, managed, and collected — their arguments are reductive and ahistorical. Their disregard for textual scholarship leads them to treat literary works as "stable and singular entities," as "self-contained and self-referential aesthetic objects."1 In this way, the distant readers are not unlike the close readers, the New Critics, waxing prosodic about a well-wrought graph.

Bode struck a nerve. The essay tore through Twitter and generated its fair share of hot takes distributed across individual blogs. The responses varied: neither Moretti nor Jockers are representative of distant reading. She writes librarians out of the picture. This method won't scale. Bode responded, in turn: of course they're not; no, she didn't; not the point. In my view, the MLQ debate was so heated (and, eventually, constructive) because Bode managed to unite disparate factions within digital humanities (DH) in a single conversation. Often described as a "big tent," DH encompasses a variety of methods beyond those practiced by the distant readers that Bode critiques; indeed, there is much internal division within the field because of the tendency to conflate "distant reading" (or, say, "computational literary studies") and "digital humanities." Bode drew on book history and textual scholarship, as well as best practices in digital preservation and archival management, to have a conversation about the limitations and affordances of large-scale text analysis. Despite the internal fissures in the field, DH practitioners off all stripes had a stake in this conversation; here was an argument that captured "DH" at its most capacious and proposed an inclusive future for digital literary studies.

Unfortunately, most of the responses rushing to defend distant reading or to quibble over sampling ignored the second half of the essay, wherein Bode outlines a major new direction for digital literary studies, one that serves as the backbone of her new book, A World of Fiction, published in 2018 by the University of Michigan Press: the scholarly edition of a literary system.

To contrast supposedly universal datasets that allow unmediated access to the historical record, Bode invokes the scholarly edition, proposing that scholars using literary data should be more attentive to the historical, infrastructural, institutional, and sociological conditions of its production. A scholarly edition of a literary text might include editorial documentation and textual annotation, archival and paratextual documents (say, maps, advertisements, authorial correspondence, photographs), and an introduction that situates the text in literary history and outlines its critical reception. So too, argues Bode, should literary data be carefully documented and understood as itself a scholarly product with argumentative aims.

Re-encountering "The Equivalence of Close and Distant Reading" as the opening parry of a book-length study, I found the argument reasonable and measured. With the benefit of hindsight, it was difficult for me to imagine how anyone (aside from Moretti and Jockers) could take issue with Bode's claims. This is not to say that her critique of distant reading or her proposal for a scholarly edition of a literary system is obvious, but that DH has changed; it is a testament to the force and urgency of her argument that the field has developed since, and as a result of, her critique. A World of Fiction ensures that the field will continue to follow this trajectory.

In the book, Bode thoroughly realizes her proposition for a scholarly edition of a literary system by building one in the form of a publicly available curated dataset, through which she investigates nineteenth century Australian newspapers via computation. She draws on distinct methodological traditions within or adjacent to digital humanities: distant reading and cultural analytics, bibliographic and textual studies, digital preservation and public humanities. She positions this capacious DH in relationship to world literature and book history, arguing for a revision of our understanding of the transmission, circulation, and reception of "extended fiction" — serialized, long-form works — within nineteenth-century Australian newspapers.

This is a book with many virtues. It deftly elaborates the relationship between process and product, exhuming scholarly decisions about data that are often buried in footnotes. It is both wide-ranging and precise methodologically. Most significantly, it demonstrates the potential for data-rich literary methods to intervene in long-standing debates in literary history, explicitly engaging the potential that more evangelistic modes of DH too often only hint at. Despite the ambition of the scholarly edition, Bode avoids bombast; in a field often mired in the rhetoric of "transformation" and "reinvention" and "disruption," her modesty is refreshing, though it risks underselling the significance of her findings. Above all, A World of Fiction is hopeful, envisioning a promising future for data-rich literary history.

In the book's first part, Bode outlines the problems with distant reading when it is divorced from book history. Chapters one and two outline her theory of the scholarly edition of a literary system, while chapter three functions as her introduction to the curated dataset. While any number of digital textual studies projects describe the processes of curation and selection, Bode goes one further: she does not merely gesture to what this curated selection could do for some hypothetical researcher: she subjects her curated dataset to rigorous computational analysis. Each of the remaining three chapters functions as a discrete analytical project, applying a number of computational methods to the data that Bode has curated: bibliometrics to consider how anonymity and pseudonymity were represented in newspapers, network analysis to show how fiction was reprinted in colonial settings both provincial and urban, and topic modeling to understand the distinct computationally-identifiable features of colonial writing. In each of these chapters, Bode shows how her curatorial choices led to argumentative outcomes.

The second half of the book makes good on the arguments of the first: Bode is not opposed to distant reading or large-scale text analysis per se.2 Rather, A World of Fiction acts as a corrective, exposing the processes (i.e., building a corpus) that often remain unexamined in favor of showcasing a method or analyzing results. The book's structure places the data squarely at the center of this project; readers would do well to shift from page to screen after chapter three, taking the time to explore Bode's dataset prior to reading the outcomes of her computational analysis.

Indeed, to speak of A World of Fiction as a book is misleading. The monograph is but one node in a large networked research project that takes many forms (including the book, a curated dataset, and "digital appendixes" that show all of Bode's computational work) across several sites (the Trove database, Bode's personal website, and the University of Michigan Press website) supported by a number of individual and institutional partners (librarian Carol Hetherington, the National Library of Australia, the Australian Research Council). Bode was ambitious in the task she set for herself, imagining her work's simultaneous release as an integrated publication event, with each publication referring to and depending on the other, and with the curated dataset at the center.

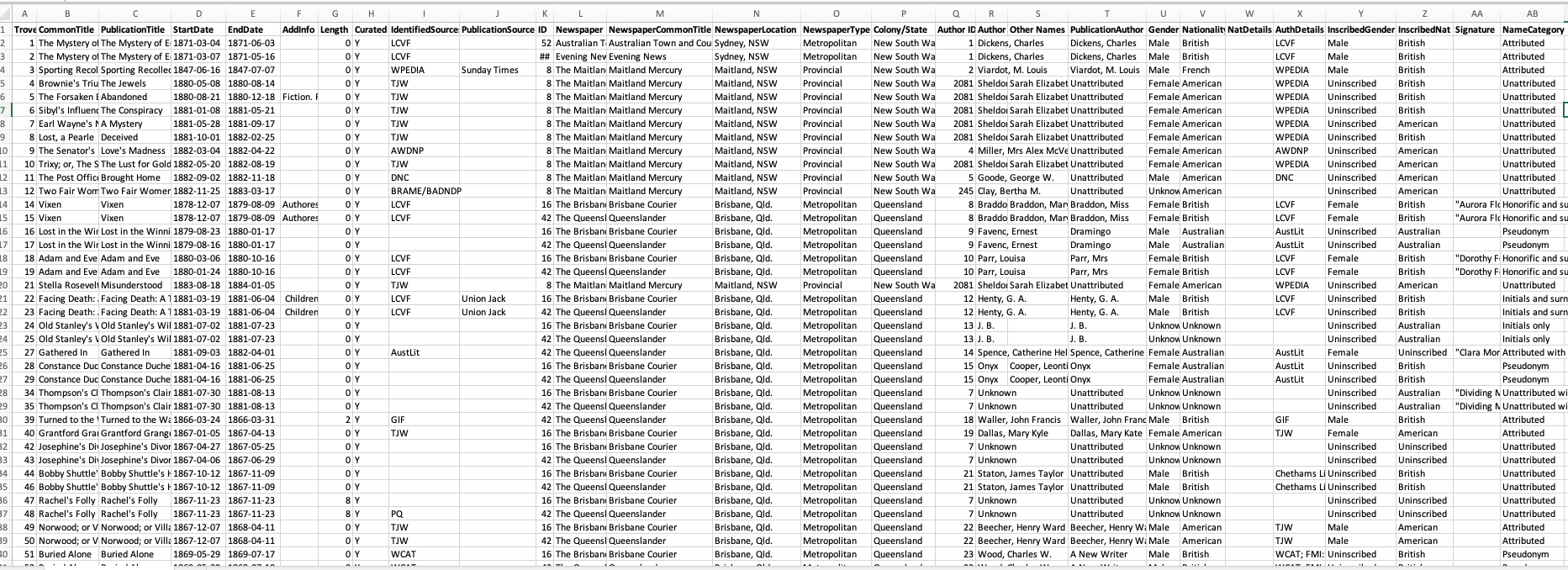

2: The window, the frame, the structure, the view

In a moment of rare but well-earned bravura, Bode writes: "For this book I did not simply theorize a scholarly edition; I built one."3 In my copy's margins, I scribbled "#fierce." To accompany the monograph, Bode developed what she calls a "curated dataset" of digitized newspapers previously collected by the National Library of Australia in the Trove database. Trove boasts an impressive repository of "21,000 novels, novellas and short stories published in Australian newspapers in the 19th and early 20th centuries," from which Bode curates her edition. Bode's dataset amounts to "a little over 9,200 works of 'extended' fiction"4; to the already existing metadata developed by Trove, Bode and her team have added thorough bespoke bibliographic metadata, including information authors (gender, nationality), publication (dates, length), and circulation (newspaper title, colony or state of circulation). This is masterful, labor-intensive work, extending far beyond the common method of publishing data as it currently exists in open digital humanities publications (i.e., publishing data in a GitHub repo).5

Bode treats the newspaper titles and her curated dataset with the meticulous care of a book historian, detailing her curatorial process in the historical introduction that is chapter three, "From World to Trove to Data: Tracing a History of Transmission." Bode shows how a scholarly edition of a literary system should be self-reflexive, attentive to the dataset's history as well as the history of the data itself. It is worth pausing to disentangle these terms: the data that Bode analyzes comes from nineteenth-century Australian newspapers. The dataset that she constructs is a different object entirely, with its own history that is equally important. Bode argues that we cannot know or make claims about literary data, let alone about literary history, without a careful understanding of how that data has come to be: who constructed the dataset, how, and why.

While this distinction between data and curated dataset may seem minor, it is central to Bode's thesis. Many distant readers, she argues, treat data as a transparent window that allows us to see all of literary history without restriction. Bode insists that we look at the window itself: that we learn about the history of the design of the frame, the architect who designed it and the builder who assembled it, the materials used by the glazier to construct the panes, how the window in the structure compares to others in the vicinity, who owns the structure and how much they paid for it, what the breeze is like when window is opened (if it opens at all), and how recently it's been dusted. Only then can we accurately assess the quality of the view.

Windows are one thing, but what of colonial newspapers? Bode presents the data, details her process and commitments in the historical introduction (not unlike an editorial introduction), and theorizes how scholarly editions can enhance data-rich literary history. She details how and why she made each of her curatorial decisions. For instance, why did she choose to include information about, say, author nationality? How did she determine nationality? What did she do when faced with conflicting information? Each of these questions has implications for large-scale data analysis.

With this data-rich history of a scholarly literary system, Bode captures not literary production, but reception and circulation. Much of the metadata that Bode includes privileges the historic conditions of nineteenth century readers. Why should an author's nationality matter to readers of nineteenth-century Australian newspapers? Might a publisher or author be strategic about the presentation of authorial citizenship, and how might that strategy differ based on readership or circulation? What did citizenship signify? Many distant readers (myself included) emphasize literary production: we work with data about when books were published, who published them, and where. By contrast, Bode situates her scholarly edition within its historical context, demonstrating the ways in which all data analysis is a matter of perspective. With her scholarly edition, Bode rejects distant reading practices that revere the authority of textual data alone, and calls on digital humanities to be more historical. (And, I would add, echoing Andrew Goldstone, more sociological.)

The difference between literary production and circulation is especially clear in Bode's discussion of author gender. Bode exhibits a great deal of sensitivity in discussing her method for ascertaining and assigning gender categories to the authors in her corpus. And she has good reason to be sensitive: as countless critics have noted, done poorly, computational methods too often rely on the essentialist M/F gender binary (sometimes ternary, with the inclusion of "Other") that excludes queer, trans, or nonbinary gender identities and expressions as mere "noise."6 Reductive and essentialist data ontologies produce reductive and essentialist results.7 Equally problematic but less remarked upon is the way that such approaches reinscribe a presentist understanding of gender — one that ahistorically emphasizes what we know now (a biographical approach) rather than the way that gender was performed and received as form of symbolic capital (a bibliographical approach). Said another way, Bode understands that gender is a performance that shapes a text's reception. This data is just as — if not more — descriptive than an author's sex as assigned at birth.

Let's say we're constructing a simple dataset about nineteenth-century British novels that includes bibliographic information (publication date, publisher) as well as biographical information (author name, author gender). All well and good with Dickens, Hardy, and Scott. What of George Eliot? We now know that George Eliot was, in fact, a woman named Mary Ann Evans. What gender should we ascribe to Evans/Eliot? Mary Ann Evans is a woman — but is "George Eliot," a nom de plume chosen because of its signification of masculinity? Neither answer is necessarily wrong—but each provides a different type of information, and answers different questions. Bode provides an answer to this problem by developing the category of "Inscribed Gender," allowing her to capture both "George Eliot" as received by contemporary readers, as well as biographical information about Mary Ann Evans. Our hypothetical database would read: Author: Mary Ann Evans; Gender: Female; Publication Author: George Eliot; Inscribed Gender: Male.

Bode uses her "Inscribed Gender" category to investigate nineteenth century assumptions about readers and writers: women writers dominate the fiction markets because fiction is read primarily by women, an assumption that is often invoked to explain the devalued status of fiction. Despite this, the majority of authors, named or inscribed, in Bode's database are men. Bode argues that higher percentage of male-inscribed texts suggests that "editors believed that their readers would be particularly interested in men's writing."8 While this finding would seem to challenge the prevailing notion of fiction's gendered status, Bode shows that, in fact, most fiction in her dataset was published anonymously. In other words, "the author — including the author's gender — was not the primary framework through which colonial newspaper fiction was presented or perceived."9 Bode's reader-centric model of a literary system allows us to capture these distinctions between authorship, editorial perception, and reception, while demonstrating the necessity of historically embedded models.

It is in the construction of inclusive database ontologies, not more complex statistical modeling, that Bode addresses some longstanding complaints about the reductive nature of computational analysis. Bode repeats this process in each of her other two computational chapters: she demonstrates how the decisions made when curating her dataset lead to results in her analysis of nineteenth-century newspapers, and how those results matter in our understanding of Australian literary history. She spares no detail, thus valuing process as equal to product.

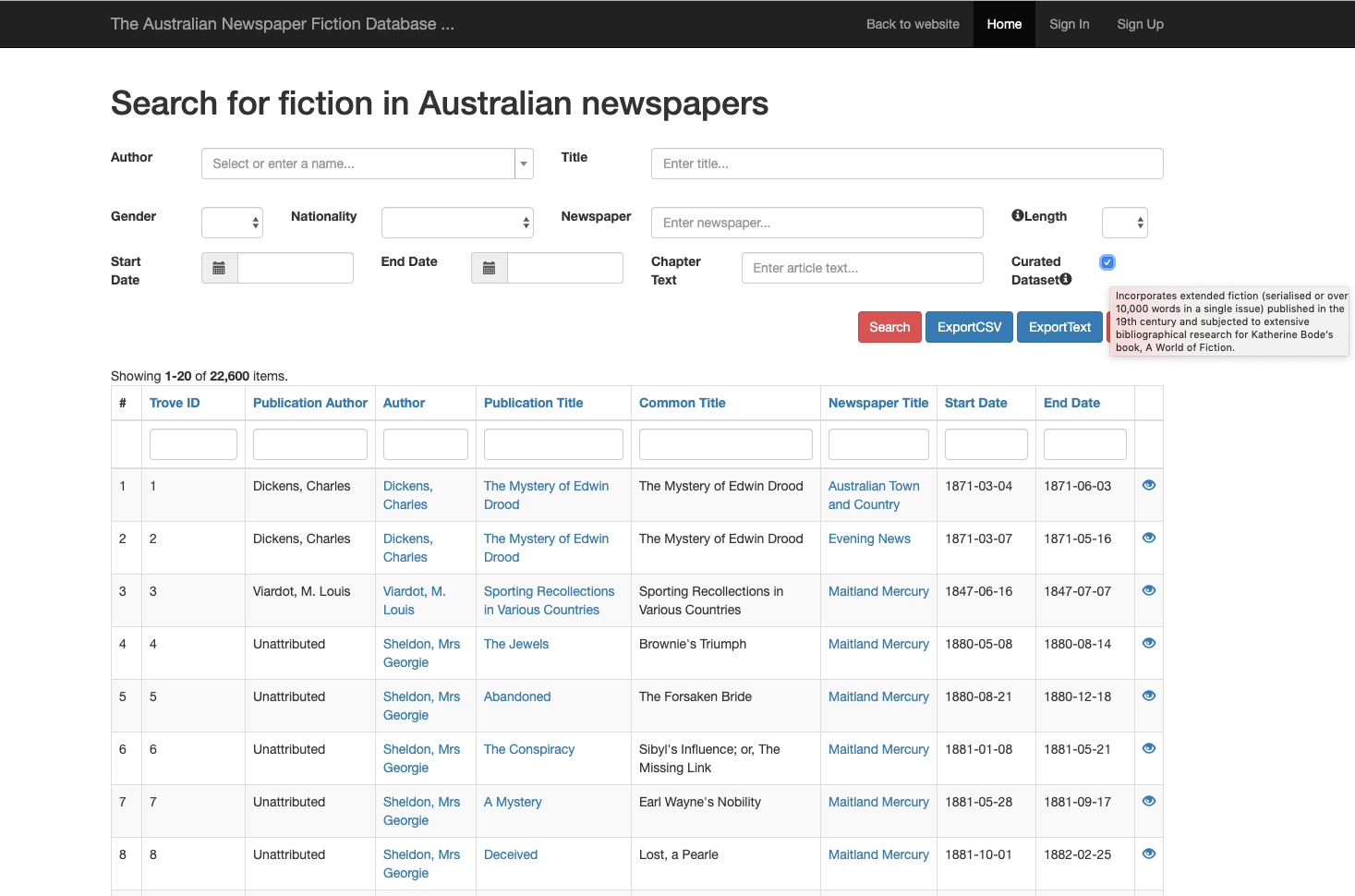

As I've already alluded, one of the greatest contributions of A World of Fiction is the public availability of data. I regret that I do not have the room here to thoroughly review the construction of the dataset, as it is a monumental scholarly achievement in its own right. I'll note, simply, that Bode's curated dataset is accessible even to users who are not technically-inclined, hosted online at "To be continued: The Australian Newspaper Fiction Database."

Groundbreaking such as it is, it appears that the project has not been without its difficulties. Though the monograph was published in May 2018, I have been unable to find any record of the data hosted at Michigan UP, now nearly a year later. (I corresponded with Bode while preparing this review, and she assures me that Michigan UP has every intention of hosting these data; it's simply taking longer than planned.) This wrinkle speaks to the infrastructural challenges of making data accessible.

But this seems a minor point compared to Bode's larger concerns about the availability of public funds to support such research. A World of Fiction concludes on a somber note: the "uncertainty in future government funding for Trove's newspaper digitization program."10 So much for exorbitant funding. While reliance on precarious data is risky, Bode is right to argue that "this situation emphasizes the continuing importance of long-standing editorial and curatorial practices for the present and future of the humanities."11 The rapid disappearance of funding makes A World of Fiction an especially urgent and generous project, as it makes data available for researchers for years to come.

3: Stop reinventing the reinvention of the field

A World of Fiction is a different sort of DH monograph than the other two reviewed in this cluster — Andrew Piper's Enumerations and Ted Underwood's Distant Horizons. Underwood and Piper address literary studies broadly; their books demonstrate that computational analysis is not only a valid method, but one with the capacity to transform literary studies. Bode's book departs from the model that Underwood and Piper follow and charts a new path for digital literary scholarship. I do not draw this distinction to suggest that Bode's argument is lacking in scope or ambition; far from it. She's doing something different.

Bode addresses more specific audiences: digital humanists, on the one hand, and Australian literary historians and textual scholars, on the other. Bode assumes a degree of literacy in digital methods and familiarity with ongoing debates that Underwood and Piper, with their detailed explanations, do not. This is my major frustration with the book: Bode's reliance on Moretti and Jockers as foils is limiting. The repeated invocation is ineffectual, doing a disservice to her forceful argument and perhaps alienating generalist readers who might otherwise be sympathetic to her argument.

Whereas Piper and Underwood make arguments about form — style, plot, genre—Bode's argument is, ultimately, historical, focusing on nineteenth-century Australian newspapers. Her historicist approach can feel limiting at times. I knew next-to-nothing about Australian literary history before A World of Fiction, and I confess that some of the finer points of Bode's argument and their stakes were lost on me. Bode's methodological provocation might not be enough to interest scholars who do not share her national or historical research interests.

With A World of Fiction, Katherine Bode insists that we do not need to keep reinventing the reinvention of literary studies. DH isn't going anywhere; we no longer need to prove our legitimacy or demonstrate our relevance to the discipline. Instead, we might turn our attention inward. We should be reflective instead of defensive about our methods. We can pursue depth over breadth, putting quantitative analysis to work to answer long-standing questions in our subfields. And there are enough of us that we can write books for each other. In other words, instead of reinventing literary studies, we can reinvent DH.

There is, of course, one final way that Bode's book differs from the others in this cluster, and from much of the prestigious work in the field: it was written by a woman. Though not framed as such, A World of Fiction is a work of feminist digital humanities scholarship. This is evident in her refusal of messianic rhetorical overtures. In the restoration of the "care work" of data curation to a place of centrality. In her rejection of binaries as she seeks creative ways to represent gender and sexuality in their complexity. In the commitment to an inclusive conversation. In the composition of her research team. In her insistence that bigger (data) is not necessarily better — especially if you don't know where it's been. I'd wager that the feminist politics of Bode's scholarship is one reason why the MLQ essay provoked outrage — and one reason why, perhaps, A World of Fiction might not receive its due among the DH monographs recently published. I hope that I'm wrong on that second point (some men will probably tell me so).

A World of Fiction is a major achievement. I hope more scholars follow Bode's model: cultural analytics will have arrived when computation is just one methodological approach among many — when a DH monograph can be simply (but not only) a monograph, and when all of digital humanities is feminist digital humanities.

Laura B. McGrath is Associate Director of the Stanford University Literary Lab and, beginning in 2020, Assistant Professor of English at Temple University.

References

- Katherine Bode, "The Equivalence of 'Close' and 'Distant' Reading; or, Toward a New Object for Data-Rich Literary History," Modern Language Quarterly 78, no. 1 (2017): 92.[⤒]

- Not only does she engage in these processes, she offers considerable praise for the Viral Texts Project (Cordell and Smith) for its close attention to the material and bibliographic record of historical newspapers, and for Ted Underwood's partnership with HathiTrust.[⤒]

- Katherine Bode, A World of Fiction (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018), 7.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- I downloaded both metadata and full text from Bode's curated dataset. I found the metadata .csv file incredibly clean and straightforward; without difficulty, I was able to create some basic visualizations in Tableau. These data could prove invaluable to Australian literary and textual scholars; it is more likely that I'll use these data in the classroom than for research. Full text was easily downloaded as zipped html files, and the process was not terribly time intensive (~20 minutes on my aging iMac). OCR is relatively clean, but upon opening a document at random, I found a few sentences like this:

ftppe^ronce, yrbich iajmndiatdy stopped jay tendency ^ may have had to tears. V^ood mprntng, Miss/' said be, 'that'a 9 PH^r ho^ yoa ®re riding, and it'a ao parly start you hare. . Are yoa {or {own E' f&ood tsonxioff, Stere,' X said, for I f^^t it ba^t 'nndcr the cir«ioitaaff.

This is to be expected from historic documents. I mention this only to stress that, though curated, text files still require cleaning. In fact, even cleaning up messy OCR like this can have an impact on results; leaving such data in their raw form, to be cleaned as each researcher sees fit, seems to be a likely extension of Bode's aims.[⤒]

- This is too common a critique to cite with any comprehensiveness. For an excellent, very recent discussion, see Laura Mandell's forthcoming essay, "Gender and Cultural Analytics: Finding or Making Stereotypes?" Debates in Digital Humanities (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019). [⤒]

- For a good case in point, see Matthew Jockers's finding in Macroanalysis (Champagne: University of Illinois Press, 2013). From a topic model cross-referenced with author metadata, Jockers determined that "genders have clear thematic 'preferences' or tendencies" in writing, including the tendency for women to "deal with expressions of feeling and emotion," while writing by men is preoccupied with using guns or swords to fight villains, enemies, and traitors (138). Man stuff. [⤒]

- Bode, World of Fiction, 100.[⤒]

- Ibid., 98.[⤒]

- Ibid., 207.[⤒]

- Ibid., 208.[⤒]