Public Humanities as/and Comparatist Practice

"Tenure. Is. Over."

I recently attended a panel discussion about the future of public humanities. Afterward, I asked a question about how a presenter's work might help rebuild tenure in the academy, and another listener, a tenured professor, replied, "Tenure. Is. Over!" This was not the first time I heard such a remark, from such a person, in such a setting. It effectively, conclusively, stops discussion. It is also self-defeating, a statement of passive acceptance camouflaged by an exclamation mark.

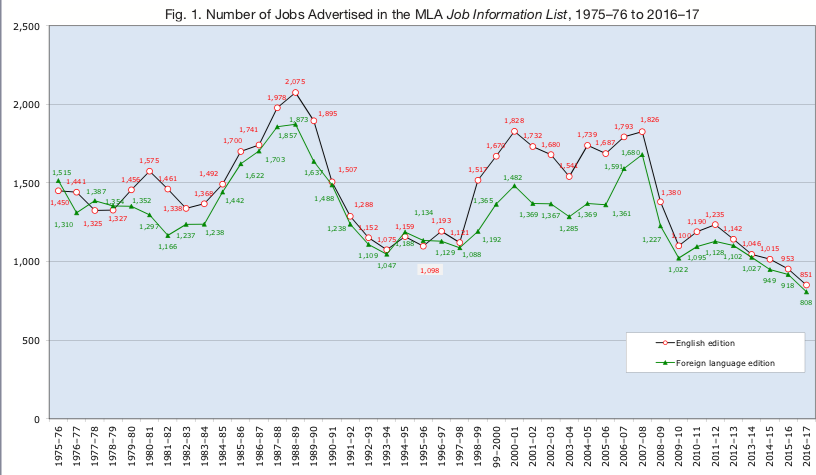

Especially since the financial crisis of 2007-2008, PhD programs in the humanities increasingly produce more literature PhDs than there are academic jobs with tenure. Increasingly, these programs encourage graduate students to opt out of academic careers and seek work in other sectors. This can feel comfortingly like action. During my four years in graduate school, I have attended and planned and participated in many career diversity and public humanities workshops and panels and roundtables.1 This paper, like the others in this cluster, originated in a conference panel on "public humanities and comparatist practice." It was a typically exhilarating experience, meeting like-minded interlocutors and hearing about their creative interventions, often unsupported by, and invisible within, their institutions, to advance public engagement with the humanities, their students' engagement with the public humanities, and their own publicly-engaged scholarship.

Such experiences are important. But they are not enough. And it is difficult to attract graduate students to such events, anyway. This surprised me at first, but no longer does. Graduate students take their cues from faculty about how to spend their time, and faculty tend to advise toward what they know best: tenure-track positions. Further, graduate degree programs in literary studies accept students not because they are great public advocates or program managers or fundraisers, but because they show promise in scholarly work. For graduate students, their scholarly work is subsidized by their writing and teaching undergraduates: faculty work. Graduate school requirements prepare students to be teachers and scholarly writers through mastering specialized terms and methods, and becoming known within self-contained networks of expertise. All of this walls off graduate students financially, rhetorically, and even socially from other sectors of the economy and society. Just completing the required work is difficult without single-minded attention, particularly with decreasing time-to-degree initiatives. Graduate students have little time or incentive to participate in activities that are not tied directly to their scholarship or teaching. Guiding them into other professional sectors is unsustainable, under current conditions: those sectors might not be able to, and might not want to, absorb excess PhDs: they often already have enough applicants trained in their field.

Meanwhile, tenure-track positions in the humanities continue to disappear. In recent years, tenure has faced open attack in Wisconsin, Missouri, Iowa, Ohio, and Washington, D.C.2 Everyone in the academy should be concerned. Individually we might feel isolated and helpless, but, as the resolution of the recent Wright State University strike has shown, collective power is still effective.3

Looking to Other Disciplines

It is time for a wholesale rethinking of our approach to public and academic humanities. We should consider how other disciplines do it. In the humanities, we are almost solely dependent on the university for funding. Must we be? The sciences, medicine, and engineering raise money from outside. Career networks, advocacy groups, and applied- and public-science organizations and journals exist to advocate for the sciences, and to financially support scientists.4

Why accept the power the academy has on our work options and operating budgets? Even with an executive branch almost absurdly hostile to federal support of the humanities, one that has proposed zero-funding the National Endowment for the Humanities for three years running, the National Humanities Alliance has demonstrated that advocacy can enhance public engagement and support for the humanities.5 Academic humanists can adopt some of the same strategies, and would be wise to make common cause with such effective peers. Doing so might require reconsidering some of our assumptions about our own expertise, but it could also remind, or clarify for, non-academics why that expertise is important to support.

Beyond the Academy

Before returning to graduate school, I spent twenty years mostly working full-time in the nonprofit sector. Practices taken for granted there could help us address some of our problems and reinvigorate the field. Nonprofits face their own problems, some of which are sadly familiar. They are under pressure to act more like for-profit businesses.6 Donations from the general public have declined.7 Wealthy entrepreneur-donors, like the robber-barons of old, use philanthropy to support pet projects and burnish their reputations.8 The nonprofit humanities remain underfunded compared with the academic humanities.9 Still, adopting practices of the nonprofit humanities would bring them into closer contact with the academic humanities, and each sector would benefit from the proximity, as is already happening in the arts.

Speaking broadly, nonprofits begin with a problem-solving orientation and an objective, whether providing services (shelter to the homeless, for example) or addressing root causes (such as organizing the homeless and their advocates to improve housing policy). They identify the parameters of the problem they wish to address and determine the scope and scale of the need. They develop strategies to implement the change they would like to see, often both short-term plans that test out solutions and address immediate needs, and longer-term plans that build and, as needed, modify the initial strategies. They describe their plans in lay terms so non-experts can understand and support them. If the need is greater than existing resources can address, they seek new resources, or find and make common cause with partners who have complementary expertise or resources. They measure the changes as they go, adjusting plans, learning from failures, and reporting to stakeholders. Academic humanists have begun to recognize the causes and scope of the job-market problem, and have begun to take action to address it, but haltingly and unsystematically, at the level of individual institutions and people. For next steps, we might look to the arts.

Partnership Across the Academic Dividing Line: The Arts

Our colleagues in the arts face many of the same challenges as the humanities. The strategies they use to address them, therefore, could provide a useful model. Artists:

- Develop partnerships across artistic disciplines and institutional divides. Artists, composers, and musical and theatrical scholars within the academy partner with local galleries and performance venues to put their work before the public. Conversely, nonprofit arts presenters make use of the resources and expertise university partnerships afford. For example, at the University of Maryland, a formal partnership with the Phillips Collection makes it easy for art students and enthusiasts to visit the museum, and for museum visitors to know what is going on at the university.10

- Welcome and communicate to new audiences. As museums funding grew too depend on people actually walking in the door, they developed methods to welcome and orient people who might not otherwise see themselves as museum visitors, like wall texts and docent tours. Today, many offer daytime tours and workshops for schools and home-school groups, as well as summer camps for children and after-hours events for adults. Such activities let non-experts discover or test out their interest in a discipline. Many arts institutions also partner directly with the public, for example through community-directed art and design. Some museums and other arts groups partner with local organizations and neighborhood groups, offering expertise, resources, and connections, but typically letting community members drive the process.11

- Present rigorously researched results accessibly. Curators work with museum educators to ensure that wall texts and education programs are rigorous and accessible. One need not be an expert in the photography of Gordon Parks or the art of silhouette cutting, the subjects of two terrific recent shows in DC museums, to learn enough to establish a foundation for further inquiry.12

- Join forces across size and type of institution. Through Americans for the Arts, cultural behemoths such as the Kennedy Center and the Smithsonian make common cause with small, local organizations and individuals; membership fees are tied to institutional size and budget, but all, large and small, can benefit from the research, public advocacy, reports, and fact sheets the association creates.

- Hold themselves and their sponsoring institutions accountable. When institutions make ethically questionable or compromising choices, artists respond creatively. Talking back to decision makers provides an opportunity to participate in defining those ethics. For example, the artist Nan Goldin organized protests at museums focusing on the Sackler family, major museum donors who own a controlling interest in Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of OxyContin.13 Goldin made the case in public that museums were benefiting from the suffering of others, and as a result, even giants such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art are reconsidering the ethics of their fundraising.

- Consider public and community work in tenure decisions. For example, a community orchestra with which I was formerly affiliated, the Burlington Chamber Orchestra, was founded by a Professor of Music at the University of Vermont, which considered the Orchestra evidence of his scholarship and creative practice, and its current Artistic Director is also a UVM music professor.14

Toward Collective Action

To save our disciplines, we need to move beyond individual and toward collective action. Preservation and creation of knowledge is our responsibility, but so is talking about that knowledge with people who know little about what we do. No one is born an expert. Insisting, however indirectly, on expertise as a basis for entering discussions of the humanities — and rooms where such discussion take place — reinforces exclusions we otherwise resist. Supporting a stronger humanities ecosystem outside the academy will strengthen the humanities inside the academy. Learning and adopting what our non-academic and near-neighbor academic colleagues do best — especially finding ways to talk about our work with non-experts, under-resourced and traditionally excluded communities, and young people — can preserve and extend what we do best. Here are my suggestions:

Talk about money. Identify gaps in funding and speak about them as problems we need help solving. Look for financial supporters from our alumni bases, and from outside the academy. Ask them to support specific projects at first. When they see us manage their gifts well, they may consider supporting general operations. If their gifts help, acknowledge that. Preparing graduate students for fundraising work, along with pedagogy and theory, is an important form of professional development. Public universities depend on the goodwill of state legislators who may only have the most basic idea of what we do. We should be aware of the sources of these funds, the infrastructure that allocates them, and the motivations of the people who provide them. If humanities deans and department chairs are not speaking to elected officials, consider who is. Conservative groups like the National Association of Scholars and Turning Point USA are working to shape their opinions about the academy. These groups are amply supported by conservative foundations with names like Koch, Scaife, Olin, Bradley, and DeVos.

Collaborate more across departments, across institutions, and even across institution types. Here are some examples of collaborations close at hand for literature departments. Offer PhD or MA students in literature the opportunity to earn certificates or dual-degrees from nonprofit or other professional-education programs. Offer literature graduate students internships, for credit or stipends, with local arts and humanities organizations and high-functioning nonprofits in our communities. Partner with nearby institutions: research universities might provide expertise and mentorship to smaller state schools or community colleges, helping their students toward a BA or graduate degree. Work with local nonprofits to offer outreach programs after school or during summer breaks, like science and technology departments do.

Our work matters for a public that needs the humanities. As individuals, there are actions we can take to tend that resource. We can advocate for our disciplines with non-experts — neighbors, elected officials, journalists, and others who can amplify our voices — and encourage them to advocate. Like our colleagues in the arts, we can recognize and, if our positions allow, speak up and out about financial and other ethical lapses, passionately, creatively, and effectively. We can reach out to and welcome new faces, including young people, non-expert adults, people from communities adjacent to our institutions, those from non-elite class backgrounds, marginalized communities, and others underrepresented in the academy. Posters for academic events are often marked "open to the public." To truly welcome the public to our events, we might bring the posters to places where publics gather, hanging them in laundromats and at bus stops. Or what if we brought our events and activities to places where these other publics gather?

We must take action collectively, above all. The recent efforts from faculty at Wright State and graduate students at the University of Connecticut and Columbia University have shown the power of collective action through unions.15 In addition, admissions committees might recruit graduate students and faculty with diverse experiences and interests beyond the scholarship they know best. Tenure committees could extend credit for public engagement. Departments could support research into what is working and not working in our management of our field, and share those results across institutional boundaries, so we are asking the right questions about what needs to get fixed, and communicating to those who care about our work and preserving the humanities. We can strategize together, at department meetings, association conferences, and other places where humanities scholars gather, to find ways to more effectively engage the public. Like our nonprofit peers, we can seek help from partners with expertise we lack. In gathering to strategize together, new ways of thinking about how to preserve our profession will arise.

Gerard Holmes is a doctoral candidate in English at the University of Maryland. His dissertation, "Discretion in the Interval": Emily Dickinson's Musical Performances, will be supported in 2019-2020 by a Dissertation Completion Fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies. He is a recipient of Georgetown University's Graduate Certificate in the Engaged & Public Humanities.

References

- I am a co-founder of a student group, Humanities Beyond the Academy, at the University of Maryland, where I have been grateful for the financial support of this project by the Center for Literary and Comparative Studies, the College of Arts and Humanities, and the Pepsi Fund, as well as pivotal encouragement and practical support from faculty and staff in the English Department and the Graduate School. [⤒]

- Colleen Flaherty, "What Remains of Tenure." Inside Higher Ed, December 7, 2016.;Colleen Flaherty, "Killing Tenure," Inside Higher Ed, January 13, 2017; Emma Pettit, "'Now Comes the Hard Part': 20-Day Strike at Wright State Has Ended," The Chronicle of Higher Education, February 11, 2019; Jack Stripling, "Catholic U. Trustees Clear Path to Cut the Faculty by 9 Percent," The Chronicle of Higher Education, June 5, 2018.[⤒]

- Colleen Flaherty, "Standing Up for What's Right," Inside Higher Ed, February 13, 2019.[⤒]

- For example, see "Mission & Vision." Society for Science & the Public. The academic sciences also, crucially, don't wait until college to start recruiting potential majors. They offer activities that engage young people early, such as discipline-specific summer camps and after-school programs.[⤒]

- Alex Nowicki. "Humanities Advocacy Day Successes." National Humanities Alliance, March 29, 2019.[⤒]

- Vu Le, "Hey, you want nonprofits to act more like businesses?" Philanthropy Daily, April 3, 2019.[⤒]

- Nicole Wallace and Ben Meyers, "In Search of . . . America's Missing Donors." The Chronicle of Philanthropy. June 5, 2018.[⤒]

- Elizabeth Kolbert, "Gospels of Giving for the New Gilded Age," The New Yorker, August 20, 2018.[⤒]

- Only about 52% of humanities PhDs had a firm job commitment upon graduation, compared with 62% of new PhDs overall. About 8% of these were in the nonprofit sector. "Job Status of Humanities PhD's at Time of Graduation (Updated June 2018)," Humanities Indicators: A Project of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2018.[⤒]

- "University of Maryland Center for Art and Knowledge at The Phillips Collection."[⤒]

- "Culture & Communities." Americans for the Arts; "Investments," Artplace America.[⤒]

- "Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now," National Portrait Gallery; "Gordon Parks: The New Tide, Early Work 1940-1950." National Gallery of Art.[⤒]

- Jasmine Weber, "After Sacklers Named inOpioid Lawsuit, Met Museum Says It Will Review Its Donation Policy," Hyperallergic, January 22, 2019.[⤒]

- "About Us." Burlington Chamber Orchestra; "Yutaka Kono," University of Vermont.[⤒]

- Stephanie Reitz, "UConn Reaches Tentative Agreement with Graduate Employee Union," UConn Today, April 9, 2018; Harris Walker, "Graduate Student and Postdoctoral Unions Officially Begin Negotiations with Columbia," Columbia Spectator, February 26, 2019.[⤒]