Feel Your Fantasy: The Drag Race Cluster

RuPaul's Drag Race cares about queer kids. Drag queens in the final episodes give advice to their younger selves. The show recites "drag family values" of accepting LGBTQ+ youth and the adults they become. Drag Race embraces more than just the queer kids who grow up to be drag queens, but also the potential benefits of being a queer child watching the show. In the show — and the show insists that in drag as well — childhood and adulthood are co-present or disrupted in drag's temporal play.

But the show does not invoke children to regurgitate the cultural fantasy of childhood innocence. There is no romantic or oversimplified relationship present between drag and either childhood or children. Drag Race invokes children and childhood to address the realities of growing up in a homophobic culture. This culture denies children's self-knowledge around gender identity and sexual expression. It polices and shames children's gender expressions out of fear of children's present or future queerness. It creates conditions for adults to reject or abandon children. It vilifies adults' queer identities and frames them as dangerous to children. The show does not shy away from critiquing homophobia and the consequences it has for queer kids. It also unapologetically asserts children as subjects with desires, sexualities, and senses of self. By focusing on the storylines of gay children, the show opens up space for cultural conversations around supporting queer kids, the relationship between drag and explorations of gender identity and sexual orientation at any age, and kinship formation as an ongoing process.

The childhood stories in Drag Race invite us to think expansively about childhood and drag queens without restricting the terms under which children and queens might be thought of alongside each other. Maybe, just maybe, the kids in and near drag are (and have been more than) all right.

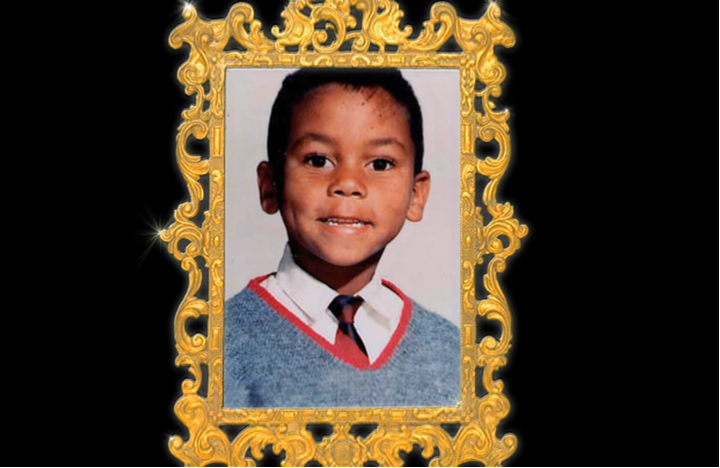

The relationship between queer childhood and drag queens frames the 2009 premiere episode of Drag Race. S1E1 "Drag on a Dime" begins with RuPaul speaking in a voiceover as still images from his youth flash on the screen. These are the same images sprinkled throughout his 1995 autobiography, Lettin It All Hang Out. In it, RuPaul writes, "At some point all gay children realize that they are different, out of sync or set apart from what everyone else is doing," reminding us these are photographs of a gay child.1 In the episode voiceover, RuPaul begins, "I, RuPaul, was born a poor black child in the Brewster housing projects of San Diego, California." The frame then cuts to black before cutting to clips of RuPaul in drag across her career. She continues,

But baby [musical interjection: "You better work!"], look at me now! As the original supermodel of the world, I had all my dreams come true. And now, it's time for me to share the love! I'm looking for America's next drag superstar.

The poor black gay child from the projects is as central to the show as the successful adult drag queen and entertainer. That child is inextricable from any narrative of RuPaul's superstardom. The child's presence in a search for "America's next drag superstar" also establishes how this is a show invested in a form of queer futurity: which gay children out there will have a chance to grow up and continue RuPaul's legacy?

The connection to autobiography is exactly to the point: at every moment in the show, Drag Race understands that the individual storylines of its curated queens are the show, just as much as any of its campy and whimsical elements. RuPaul's own gay childhood visually establishes the show's many participants and trains its viewers on how to encounter them: the gay child is the drag queen superstar is the host is the potential drag queen superstar contestant is the viewer, who is also a potential drag queen superstar (and, doubtlessly, a critic). At the conclusion of that very first episode, Victoria Pork Chop is famously the first queen to be eliminated. Upon revealing her decision, RuPaul says, "I hope you take this experience back home with you and continue to do what you do best and inspire the children." While "children" may refer to the drag children of drag houses headed by drag mothers, RuPaul is also talking about actual children, the little RuPauls and Pork Chops who might look at RuPaul and Pork Chop and see themselves.

The copresence of queer childhood with current drag queens is literalized in a feature that recurs across many seasons. RuPaul shows each semifinalist a photograph of herself as a child and asks her what she would like to say to her younger self. Some precursors to this occur in 1) S2E8 "Golden Girls," when the remaining queens have to match all of the season's contestants with their baby photos in a mini-challenge, and 2) Untucked S5E7 "RuPaul Roast," when the queens' baby photos appear on the room's screen. In the latter, Jinkx Monsoon's emotional reaction to her photo leads to Roxxxy Andrews' painful revelation that she was abandoned at a bus stop at the age of three. The queens don't have a straightforward "It Gets Better" moment with these photos. Their emotional reactions to these portraits reflect, instead, on the continuity of challenges they have faced. The assimilationist impulses behind "It Gets Better" — the desire for celebratory narratives of overwhelmingly white adult homosexuals who have overcome their struggles through stable marriages, having children, and acquiring capital — are abandoned in favor of the differential struggles its many contestants, as a multiethnic cohort of queer people, experience across their lifetimes. Of course these struggles might be co-present with pleasure, joy, and community and even resonate with some of the metrics of success according to "It Gets Better." Being on the show is arguably a measure of progress in and of itself, and it enfolds each queen into the Drag Race family and its attending fans, merchandise, branding opportunities, and rate-increase-post-televisual-appearance. But Drag Race refuses the demand for neat, respectable adult queers whose respectability ensures their universal acceptance and freedom from harassment upon exiting queer childhood. In this way, the show offers an important alternative to media that resolve queer childhoods with rainbows and state-sanctioned modes of inclusion, attachment, and belonging.

Beginning in Season 7, drag queens talking to their younger selves becomes a set piece in the show's narrative arc. In S7E12, RuPaul explains that she's so proud of "her kids." Across this and later seasons, queens regularly recognize the queerness of the children to whom they are talking. Kathryn Bond Stockton notes how often in US culture, the gay child can only emerge in retrospect. Gay adults can look back and recognize the gay children they were, but culture desires for asexual-but-future-heterosexual children.2 These desires inform the disciplining that emerges, for example, in schoolyard and cyber bullying, state laws around sex education, and attempts to censor children's media. We see these cultural desires manifesting in the recent passage of Florida's Parental Rights in Education Act (better known as the "Don't Say Gay" act) and the passage of laws in Alabama, Arkansas, Texas, and Arizona (with other states trying to follow) that limit or ban trans youth's access to gender affirming care. These cultural desires work to prevent LGBTQ+ children from being presently queer in the time of childhood. RuPaul's inclusion of drag queens' baby photos and the conversations between drag queens and their younger selves acknowledge and enflesh queer children beyond linear trajectories or simple resolutions. In talking to their queer child selves, they are also talking to the queer youth audiences whose existences are being criminalized, outlawed, and restricted.

These younger selves sometimes inspire contestants, but they can also wreak havoc on the drag queens' work. RuPaul frequently invites queens to consider how their "inner saboteur" is at play when they are struggling on the show. These "inner saboteurs" are more often than not versions of the queer child. For example, in Drag Race UK S4E10 "Grand Finale," RuPaul asked Black Peppa why she had difficulty in the acting and humor challenges. Black Peppa replied, "That child in me has always had that doubt, because my parents [were] like, 'No, you can't, you're not allowed to do this, you can't do that.'" RuPaul urged Black Peppa to care for her "inner child" in order to keep growing. The recurrence of the inner saboteur/inner queer child across the series is another way the show's language and thematics insist on narratives beyond triumphal accounts of queer childhood that resolve into respectable queer adult stories.

The challenges in Drag Race are rife with age play — queens pretending to be babies, elders, teens, and everything in between. In general, playing with time — both in terms of past references but also in terms of age — is a hallmark of drag. Elizabeth Freeman describes drag's temporal play as the "act of plastering the body with outdated rather than cross-gendered accessories."3

One particularly layered example of age play is in S10E7 "Snatch Game," when Eureka O'Hara plays Alana Thompson, better known as Honey Boo Boo of TLC's reality shows Toddlers & Tiaras (2009-2013; 2016)and Here Comes Honey Boo Boo (2012-2014). The former TV show was about Alana competing in child beauty pageants, the latter a spinoff about her family's day-to-day lives in Georgia. Part of what makes Eureka's choice particularly apt is that child beauty pageants are drag shows — girls dressing as women engaging in gender fuckery as they vie for a crown. Several participants in Toddlers and Tiaras evencite RuPaul as a major influence.4 RuPaul herself has praised Alana, noting that "she understands what drag is. That's what pageants are."5 I'm suggesting here that in deciding to compete as Honey Boo Boo, Eureka became the first Drag Race contestant to choose the character of a child drag queen. Eureka's top performance works because Eureka and Honey Boo Boo have twin energies: unapologetically taking up space, being loud, brash, silly, and confident. Being in drag as a child lets Eureka show off what makes her a strong drag queen but also what also subjects her to ridicule out of drag. In the same episode, and in another example of age play, The Vixen plays Blue Ivy. Because her rendering was more muted, she landed in the bottom two. The Vixen wasn't able to campify the ways Blue Ivy is expected to conform to white-determined respectability politics because of the scrutiny she is under as a Black girl. In 2015, Blue Ivy was at the center of a controversial Difficult People episode, which drew attention to the way she and other Black girls are available for sexualization in the public sphere under the guise of comedy.6 Invoking Blue Ivy in a comedic space in Season 10 (2018) was perhaps a politically engaged choice. Later in the episode, when discussing drag that explicitly engages politics, The Vixen states, "A lot of people say drag should only be an escape from reality, but drag can also help us face reality and deal with it." The Vixen's eschewing of an over-the-top comedic performance for a restrained performance perhaps reflects on the racialized norms that police Black girls' behavior in public. In the critiques, the bottom-performance of Blue Ivy versus the top-performance of Honey Boo Boo became the vehicle for staging the ongoing drama between The Vixen and Eureka. The show edited the campy performance of white poverty as the foil to the non-campified respectability of Blue Ivy, giving credence to The Vixen's larger concerns over the ways racialization comes into play in the show and the drag community more broadly.

Drag Race has been on the air since 2009, and queens as young as 19 compete on the show. This means that some queens grew up watching the show. RuPaul has dubbed these generations "literally the children of Drag Race," capturing the ways that these queens are encountering drag not exclusively (if at all) through sneaking into gay bars and clubs but by logging onto social media or tuning into VH1.7 While the show's move from Logo to VH1 has been critiqued for its mainstreaming (that is, its commodification and domestication) of drag, the move likely increased access to the show for queer youth. Airing on VH1 doesn't automatically mean all queer kids can access the show, but queer kids across generations have been resourceful, whether through reading Vogue magazines by flashlight under the covers or, perhaps now, hacking their devices' parental controls to stream Drag Race. The show's shift to platforms and social media increasingly accessible to youth has led to the rise of "Instagram queens," a term often disparagingly used to denote a queen who is invested in aesthetics, likes, and follower counts but can't perform, lipsync, or do comedy for live crowds. While these queens might know that performance is key to success on Drag Race, they have found fame and fans online. The generational tension between so-called Instagram queens and old school queens (or queens who otherwise mark themselves as different than this youthful generation because of their focus on live performances) is another effect of Drag Race on queer childhood. Children are encountering drag in their contexts — environments that are largely virtual and where being perceived as funny, beautiful, and like a superstar rely on different tools, techniques, and norms than those for queens operating in nightclubs, bars, and brunches. Children are learning one version of drag from a television show and then executing it in the surroundings available to them. That Drag Race is a (if not the) touchstone for many queer kids to encounter queer community, culture, and history cannot be denied — how these effects on queer childhood will play out remains to be seen, as younger queens continue to enter the scene and as drag continues to be an evolving, and increasingly mainstreamed, art form.

Drag Race does not present a utopic vision of queer community for its adult and youth audiences: the show's success is driven by the contestants' constant spilling of tea and throwing of shade. The competition is famously "not RuPaul's best friend race," and like all families, queens fight, gossip, and stir the pot as they navigate challenges in the pressure cooker of a reality television show environment. Each season has at least one queen who gets "the villain edit," but this framing sometimes provides a nuanced opportunity to disrupt a one-dimensional, reductive conception of villainhood through invoking drag queens' queer childhood pasts.

For example, Phi Phi O'Hara was infamously the villain of Season 4 (and failed to get a "rudemption" narrative in All Stars Season 2, which ultimately contributed to her cutting ties with the franchise). However, S4E10 "DILFS: Dads I'd like to Frock" presented a rare vulnerable side of Phi Phi. The challenge tasked queens with making over heterosexual fathers as drag queens. While on the mainstage, Phi Phi's voice falters talking about how her life would have been different if she had a father like her drag partner. Later in S4E14 "Reunion," the rest of the queens extensively criticize Phi Phi for her ruthless behavior that season. When RuPaul interviews Phi Phi, she says,

I came in here to win . . . but I wanted to be the backbone and strength for a lot of those kids that had to go through, like, a child abuse past.

She breaks down as she reveals she is still estranged from her father and then shares words of encouragement for any kids watching.

On one hand, the connection of Phi Phi's villainhood with her struggles as a queer child — presented in a slow burn across the season and then juxtaposed very directly in the reunion/finale — might be an attempt to both humanize and explain (though not excuse) some of her behavior. Her hard exterior and cut-throat style are in this scene presented as products of lifelong queer defense and survival. But this background doesn't redeem her — she's still the villain at the end of the show. Enduring queer childhood doesn't make anyone into an adult queer saint - Phi Phi's edit rejects the respectable adult of the "It Gets Better" movement in favor of a flawed queer adult. Phi Phi also doesn't believe her behavior disqualifies her from being a model for queer youth today. While Phi Phi is emotional as she talks about how she wants to give hope to queer children, queer childhood is ultimately anti-sentimental. Queer childhoods yield complicated, fully human queer adults on Drag Race who argue, talk shit, and unapologetically throw their fellow competitors under the bus.

Capitalizing on her ongoing moment, RuPaul, with Michael Patrick King, created a Netflix series about a queer kid and a drag queen's mutually beneficial relationship. In AJ and the Queen (2020), Ruby, a drag queen played by RuPaul, travels the country to make money after being scammed by her con-artist-boyfriend. She is unwittingly accompanied on the trip by semi-orphan, tank-top-and-beanie-wearing AJ. AJ is short for Amber Jasmine. She tells Ruby she's named "after [her mother's] stripper friend and a racist Disney cartoon." Her proximity to all things opposed to childhood innocence is reiterated across the show. AJ has painfully acquired virtues of independence, self-sufficiency, and hustling — not unlike many of the queens who have competed on Drag Race. Across their journey, Ruby acknowledges all of this in an anti-sentimental way in order to affirm and recognize AJ's personhood, autonomy, and hard-earned life skills. (This is the drag version of Horatio Algers Jr.'s Ragged Dick — a queer title if I ever heard one!)

Ruby and AJ's conversations explore generational tensions at play within many LGBTQ+ communities. In S1E2, "Pittsburgh," Ruby asks AJ why she dresses like a boy; AJ turns the question on Ruby asking why she dresses like a girl. When Ruby continues to press AJ, AJ retorts, "Do you want to be a girl?" Ruby says no, and AJ affirms the same lack of desire to be a girl. Later, when talking with her friend Louis back home, Ruby expresses confusion over AJ's identity, claiming, "She identifies as a boy. Or actually I'm not sure where he or she or they is on the gender non-binary scale." Louis reminisces about how it was "simpler" for them "growing up," when "there was just two choices. Sissy or tomboy. You're done." Ruby and Louis link themselves with AJ in their experiences of "gender issues" (Ruby's phrase), but the modes for material and discursive expression have shifted. While Ruby and Louis might not understand how to identify AJ, they do identify with AJ's struggle with gender expression.

A later conversation between Ruby and AJ bridges some of what at first seem like chasms. Ruby asks AJ, "Why are you always saying you want to be a boy?" AJ asserts, "I never said I wanted to be a boy . . . I said I didn't want to be a girl." Ruby, confused, asks, "So if you don't want to be a boy, why are you pretending to be one?" AJ responds, "Because people leave boys alone."

AJ articulates a subtle but important distinction to Ruby about how not wanting to be one gender doesn't automatically mean one wants to be another gender. Ruby assumed that AJ's ambivalence toward girlhood meant she was trans or non-binary. Perhaps AJ is or will be one of these, but importantly, her articulation of her relationship to gender causes Ruby to consider her own generationally-inflected assumptions of present-day queer children. Ruby reflects, "It's funny. I made my whole life about not letting people put me in a box, but I go and put you in one. A forward thinking politically correct one, but still a box nonetheless." Ruby realizes that for all the ways drag and queer culture have invited her to disrupt gendered categories, her default approach to the queer child in front of her recapitulated some of the rigidity she herself rejected. This is one of many instances in the series where drag queens and childhood are presented in non-oppositional modes; the generational tensions that Ruby and AJ tease out invite both to look toward one another as someone to learn from and with.

Recent seasons of Drag Race have increasingly featured trans and non-binary contestants. Some have argued this is RuPaul saving face after her 2018 statement that trans women who have undergone medical transition probably shouldn't be eligible to compete on the show. (RuPaul later apologized.) Recent casts alongside these exchanges in AJ and the Queen perhaps reflect RuPaul's attempt to engage in cross-generational learning, which involves mistakes and misunderstandings and requires revisions of assumptions and norms, in addition to repair. As in AJ and the Queen, it's trans and non-binary drag queens who have helped RuPaul get there.

A bonus: When AJ insists that Edie, a drag queen played by Jinkx Monsoon, take her to the bar for a burger, Edie declares, "First kid I ever met who's a top!" The show doesn't fear children's proximity to sexual irreverence or humor. AJ — and many other kids — have plenty of sexual knowledge, and the show dares to bet that a gay joke will not incur material and epistemic harm to the child, who is constantly encountering (hetero)sexual pressures and projections elsewhere.

Not all children drawn to drag are current queer children, though many are. Countless responses and defenses of children and drag have downplayed or straight out denied that there's any sexual, queer, or gender identity component to drag in order to justify or mitigate children's relationship to drag. This strategy, however, does not help children or drag queens. Instead, it participates in the homophobic culture in which children and drag queens must already operate under the guise of inclusion. It also vilifies the drag queen adults that were queer children and who understand the need for seeing models, mentors, and templates for survival, existence, and flourishing, especially when operating in contexts that police, shame, and reject queer children for expressing themselves. Drag Race supports the children, and many lawmakers, politicians, parents, teachers, and professionals could take a page or two from the Drag Race oeuvre — the library is open.

Mary Zaborskis is Assistant Professor of American Studies and Gender Studies at the Pennsylvania State University - Harrisburg. She works at the intersections of queer, critical race, and childhood studies in twentieth-century and contemporary American literature and culture. Her book manuscript Queering Childhoods (forthcoming in NYU Press' "Sexual Cultures" series) explores the management of children's sexualities in boarding schools established for marginalized populations in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Her work has appeared in GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, WSQ, Feminist Formations, and Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. Mary is a series editor at Public Books.

References

- RuPaul, Lettin It All Hang Out (New York: Hyperion, 1995), 19.[⤒]

- Kathryn Bond Stockton, The Queer Child, or Growing Sideways in the Twentieth Century (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2009).[⤒]

- Elizabeth Freeman, Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010), xxi.[⤒]

- Alexis Tereszcuk, "Toddlers and Tiaras Get Their Inspiration," Radar Online (December 7, 2011), https://radaronline.com/exclusives/2011/12/toddlers-and-tiaras-kids-get-their-inspiration-rupaul-video/.[⤒]

- Sophie Schillaci, "RuPaul Honey Boo Boo Duet," The Hollywood Reporter, September 11, 2012. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/music-news/rupaul-honey-boo-boo-duet-369549/.[⤒]

- Emily Yahr, "Amy Poehler's Difficult People Slammed For Blue Ivy R Kelly Joke," The Washington Post (August 19, 2015), https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/arts-and-entertainment/wp/2015/08/19/amy-poehlers-difficult-people-slammed-for-blue-ivy-r-kelly-joke-heres-why-its-extremely-meta/.[⤒]

- Ciara McVey, "RuPaul Teases Young Diverse Contestants," The Hollywood Reporter (March 21, 2018), https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/general-news/rupaul-teases-young-diverse-contestants-rupauls-drag-race-season-10-studio-1096026/.[⤒]