Feel Your Fantasy: The Drag Race Cluster

It's not simply that the couch juts into the camera's frame, but that it is a bronze couch. Bronze with a garish sheen. A glossy bronze befitting a vintage 1970s gay porn shoot. A bronze couch sharing space with a faded black leather chair and brocade maroon curtains, all those clashing textures and colors. Then there's the rather ugly blue lamp and orange lamp lighting up the room, glitzing up the bronze of the couch, making noticeable all the various prints hanging on the wall. This living room business is ordinarily no part of a grand finale episode of RuPaul's Drag Race. Showing off runway looks and lipsyncing for your life are not supposed to be undertaken in a contestant's cramped apartment, or a building's grimy roof, but, especially after Season 4, taped in front of an audience at a luxe Hollywood theater, with dazzling lighting torpedoing about and ear-popping audio. Alas, when a global pandemic strikes, one must respond accordingly, hopefully responsibly, and the bronze couches and black leather chairs and maroon curtains and ugly blue or orange lamps of the queer domestic sphere make their grand debuts. In the case of the Season 12 contestants, they achieve the dismaying feat of being the first quarantine grand finale. The seemingly seamless production of Reality TV finds itself disrupted by and unable to use TV magic to avoid the reality of a global pandemic. Couches pop up everywhere in this digitally experienced domestic world.

When Crystal Methyd takes the (living room) stage to showcase her grand finale entrance look, she, in her typical quirky, clownish style, is a lifesized donkey piñata sporting long, curly lashes. Quirky drag aesthetics like Crystal Methyd's revel in the unserious, the idiosyncratic, and the peculiar, tantalizing audiences by deploying the wacky as an aesthetic strategy. Unlike camp, which Susan Sontag qualifies as a, "sensibility of failed seriousness", quirkiness as an aesthetic category thrives in unserious and idiosyncratic intentionality.1 At first blush, quirkiness might bear relation to zaniness as theorized by Sianne Ngai, in the shared playfulness of the categories, but it lacks the hyperactive or overworked franticness ascribed to the zany, "an aesthetic of action" premised on "the 'putting to work' of affect and subjectivity for the generation of surplus value."2 The zany, according to Ngai, operates according to capitalist systems fueled by precarious forms of gendered and racialized incessant labor. Unseriousness and peculiarity drive quirkiness, not degrees of vigor or vitality, spotlighting whimsical personality and lighthearted character above all else. The seconds-long entrance recording in her living room begins with her blowing confetti out of her piñata mouth and ass, accompanied by humorously trumpeted party sounds. She bobs back and forth, a cheesy smile plastered on her signature made up face, the camera following her throughout the living room, primarily through close-ups and medium shots. Two kitschy, relatively dim lighting fixtures stand at either end of the camera's apparatus, and an electrical outlet and a cord rope across the floor, boldly visible to the audience. At the corner of the camera frame is the bronze couch with a rustic, grandmotherly white pillow resting atop it, the pillow adorned with a blue stitched rabbit and other nature-inspired designs.

When I first watch this finale episode (myself in quarantine), I think it unfitting, and unfair, for such a whimsically absurd and innovative piñata embodiment to have to be shown off in one's living room. That bronze couch, there in the camera frame, brashly displayed! The living room stage feels unequipped for the larger-than-life wackiness of piñata drag. The bronze couch interjecting into the frame, too glaring a reminder of the quarantine quotidian, of being stuck at home both bored and worried, hoping for everything to be okay while longing to be at the queer bar watching RPDR live with others, a drag queen emceeing and lipsync sprinting between commercials.

Her imaginative piñata look in a cramped, kitschy living room is, putting it bluntly, disorienting. I am used to the (post Season 4, the first season where the winner won $100,000?) high budget, masterfully edited project that is RPDR. I have come, inadvertently, embarrassingly, to largely associate the art of drag with RPDR, and RPDR's global televisual enterprise has made such an association common-sense. RuPaul's televisual empire holds a firm grip over what kinds of drag art and styles popularly acceptable, praiseworthy, and profitable. Crystal Methyd's wonky, charming, and over-the-top queer DIY Mexican romp in a curly-lashed piñata within her living room disturbs the RPDR spell. A later rewatching (two years out of my 2020 quarantine) I find the living room realness effect enchanting, and befitting a quirky Latinx queen like Crystal Methyd. The cramped living room with its 1970s-porn-shoot-ready bronze couches, too, can be a site where drag, where queer gendered performance, takes place and thrives. The Latinx eccentricity and the most uncommon of drag aesthetics of a queen like Crystal Methyd can shine in the unlikeliest of places if we allow ourselves to indulge in it.

What is drag beyond the high-budget televisual spectacle? Or, say, the very much politicized reading hour at the public library that has become the subject of nationwide debate? Or, dare I query, what is drag beyond the wildly popular drag brunches convening cishet women into boozy midday chaos? Drag is all these things, deeply politicized by conservatives and commodified by capitalists and fetishized by cishets, yes, but it's more than all of that. The quarantine finale episode of season 12 highlights the trouble drag performance and reality television — whether in the local instance of the drag bar or the spectacle of prime time — have when the standard means of showcasing drag are altered (can't go to bars, production venues and filming techniques must change). Audiences have grown accustomed, and in fact have been primed by the televisual apparatus, to certain standards and conventions of how drag is to be presented and consumed. Drag enthusiasts and queer people become "we're just like you" reactionaries when conservatives denounce drag queens reading to children, combatting our oppressors on the very grounds of respectability familiar and amenable to them. The disruption of the quarantine finale episode, of that giant, madcap piñata next to a bronze couch, proves unsettling at first, but it also serves as an important reminder of drag's quotidian manifestations even within the spread of its global influence. The young queens and makeup enthusiasts across the world sitting on couches watching drag makeup tutorials on Youtube. The many scuffed up couches, many probably in bronze, in queer bars that serve as front-row seats to drag performances. The couches viewers sit on at home, watching the many national versions of RPDR and spinoff shows, or for house parties where friends come dressed in drag for the evening. The televisual intrusion of the couch in Crystal Methyd's grand finale entrance look only works to confirm how such cushiony fixtures are significant sites of everyday encounters with drag. These everyday, local instantiations, thanks to social media, streaming services, concert tours, conventions, and other mediums for distributing drag, make for global consumption. Anyone across the world, presumably, can experience the aesthetic specificities of drag personas, traditions, and styles, making experienceable, say, the particularity of a queer Chicanx clown queen like Crystal Methyd, no matter where one resides or the cultural knowledges they may be familiar with. In this case, the global is always ever a manifestation of and encounter with the local, with audiences experiencing contexts, histories, and social particularities that readily disseminated drag proffers.

The delightful and pleasurable piñata wackiness performed in a cramped living room with a bronze couch ignites another sense of drag. Drag that is not exclusively about the glitz and glamor can look, as one critic aptly summarizing Crystal's grand finale entrance notes, like "horsing around at the finale as a huge festive piñata while her competitors went for more classic glamour."3 Drag that is not solely about the catty or contriving. Drag that is not about having the biggest budget or most expensive gowns. Here Crystal Methyd joins in with an ensemble of other cooky, weird, crafty, and quirky queens of color. Think here, for instance, of season 6 contestant, Vivacious, and her conceptual Club Kid-esque antics, or season ten contestant, The Vixen, who constructed many unique outfits for her runway looks. Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes assesses how season one contestant Nina Flowers stood out for her punk looks and bilingualism that were " in dramatic contrast to the more traditional feminine style of other contestants."4 Season 11 winner, Yvie Oddly, (true to her name) exemplifies this oddball aesthetic best, always showing off the most exuberant outfits and kooky performances. What often transpires for these innovative, wacky, eccentric queens of color, especially the Black queens, is that they are evaluated according to a trenchant and seemingly unswerving respectability politics. They are critiqued for being "unsophisticated," "unpolished," and strongly urged to showcase more glamorous and conventional drag looks (read: expensive, pageant-like aesthetics and makeup, made to seem properly and opulently feminine). The quirky, DIY, and eccentric queens have a harder time being appreciated on their terms, for their aesthetic and performative strategies, even if those very looks require the same, or more, upfront costs as pageant or "look" queens who outsource the construction of their looks to designers. Though quirky drag aesthetics are incorporated into the expensive, commodified RPDR conventions proliferating as part of the televisual franchise and in various drag scenes, it is not an aesthetic easily commodifiable by capital as other types of drag, especially racialized queer lowbrow quirkiness that disrupts highbrow glamor and respectability politics. Nor is it intrinsically tied to craftiness, or queens constructing their own looks from scratch. Quirky drag aesthetics are about the wackiness of expression and performance combined with the labor of drag's construction, the playfully unserious pleasures of being a weirdo and goofster, It's an attitudinal comportment that elicits from the viewer joy in a quirky vibe rather than in opulent beauty or comedic sassiness. It can be drag on a dime, if necessary, simple and unfussy drag, if desired. Piñata drag like Crystal Methyd's doesn't take itself seriously, and this is the source of its pleasure.

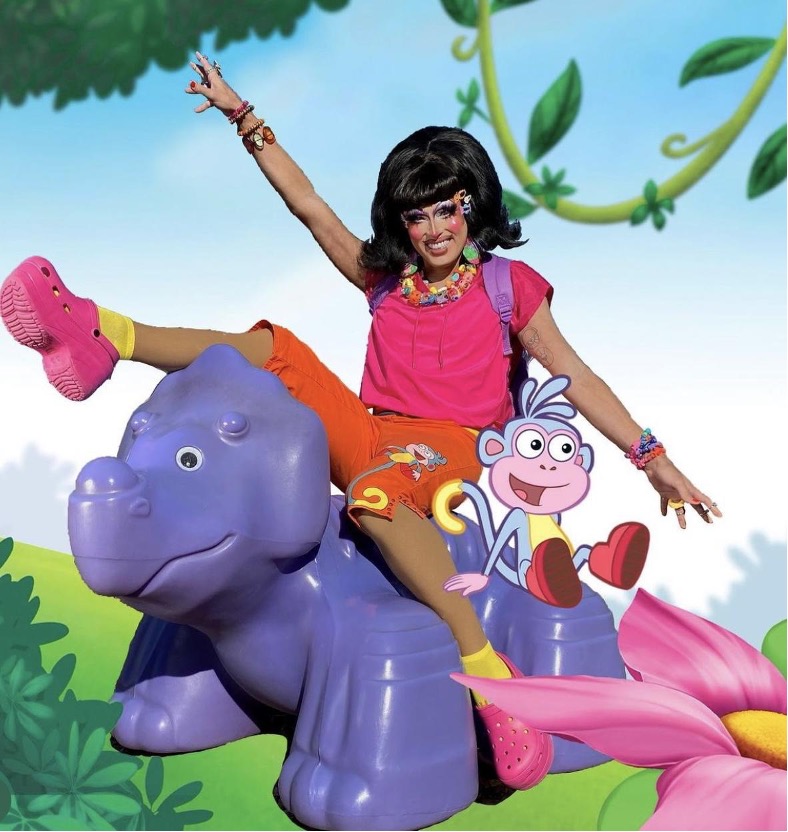

Crystal Methyd as an oversized piñata in her living room shows us that gendered performance, play, and pageantry is not just about mimicry, conventionality, glamor, or televisual pyrotechnics, but also holds and promises aesthetic absurdity, pleasurable silliness, queer and racialized eccentricity. Piñata drag indexes the ridiculous, nonsensical, and, above all else, the pleasurably entertaining. Take, for example, a look Crystal Methyd posted to her Instagram page: Crystal does Dora the Explorer drag. She dons the signature Dora wig, pink shirt and orange pants, with a photoshopped Boots monkey companion at her side. She sits atop a grimy, weather-worn plastic purple dinosaur you might find in a playground or backyard.

In a video posted a few days later on her Instagram, she wears the Dora getup and clowns around in a children's playground.5 The Dora the Explorer opening audio track plays as she performs her antics, sliding down slides and swinging on swings, ending the brief video with a slapstick-styled crashing to her ass while attempting to mount the plastic purple dinosaur. In another video post, she dances as Dora in the playground, popping her ass, the caption of the post reading, "When did Dora the Explorer get THICC!?"6 Crystal Methyd's various posts as Dora are ridiculously silly, ridiculously wacky, and charged with Latinx nostalgia and identification. Dora the Explorer has become a character easily troped, a symbol of racialized Latinx excess originally targeted for children but now widely parodied (before Crystal Methyd's Insta posts, Season 6 winner Bianca Del Rio did Dora drag for her Snatch Game audition tape.7 The racial signification of Dora drag might be considered in relation to drag impersonations of a figure like Selena, a persona Latinx drag queens often take on. Deborah Paredez characterizes Selena drag "as a means by which to grieve, survive, educate, and camp it up — Latina/o style."8 With these aims, Selena drag impersonations often aim for mimetic realism of the singer (renditions on her iconic outfits, similar hairstyles, signature Selena movements, lip shape and color, eyebrows, contour) and a degree of aesthetic seriousness tacked on to the impersonation. On the contrary, the nature of Dora drag, like piñata drag, is markedly unserious, silly, playful, absurd, and humorously parodic. Queer Latinx eccentricity and quirky entertainment is the point.

Crystal Methyd as Dora the Explorer or a donkey piñata demonstrates the aesthetic pleasures of quirky drag. We witness how stereotypically overcharged objects and characters become pleasurably retooled, made the focus for humor, a project of queer Latinx quirkiness we can all laugh at and delight in. There is a distinctive and unique pleasure in drag art like Crystal Methyd's where idiosyncratic goofiness and clownery takes center stage, where a performer allows, and yearns, for an audience to celebrate their ham-fisted and kooky antics. RPDR is chock full of queens who espouse aesthetics of overwrought sophistication and snappy, sassy comedic seriousness. Crystal Methyd makes her queer Latinx body and drag art the site of humor, from her distinctive clownish makeup style to her slapstick antics, unafraid at looking ridiculous and compromising seriousness. Her project of queer Latinx quirkiness invites us to take humorous pleasure in all that she is and serves up.

Before the Season 12 finale episode, Crystal made an appearance as the donkey piñata on Monét X Change's YouTube show, The X Change Rate. "You can't have a party without a piñata," she says to Monet.9 Allow me to slightly remix her phrase: You shouldn't have drag without a piñata. You shouldn't have drag and gender performance without our quirky piñata queens and sensibilities, the racialized queer clowns and goofballs who dare audiences to laugh at them for all that they are. You shouldn't have drag without the clashing aesthetics of bronze couches and donkey piñata gowns, or Dora drag in a children's playground. I don't want to imagine drag without the weird and the wacky, the uncommon and unseemly, the slapstick and the silly. Crystal Methyd falling on her ass off the purple plastic dinosaur on Instagram reminds me of a time when I was at a queer bar on a RPDR night. It was some season of All Stars, a drag queen was emceeing, and I wasn't there to indulge in RPDR but it just so happened to be on while I was catching up with a friend. Suddenly, during a lipsync in between commercials, the drag queen started doing wrestling-like tumbles across the bar's hardwood floors. Admittedly, they were not the most well-executed tumbles, nor the neatest, and the resounding smack from the impact of her body hitting the floor was astoundingly jarring. Each time she arose from a tumble her brown wig was more lopsided and frizzier than before, a pigeon's nest in dazzling movement. I couldn't focus on the conversation I was having with a friend, delighted by her chaotic acrobatics and disheveled wig, and thought to myself, "Wow, she's a mess." And I meant those unspoken words warmly, a glowing evaluation premised on her successful achievement at entertaining and charming an audience, by any means necessary, a performance of exuberant messiness. I tipped her, applauded, as she continued on with her performances through the night. This is what drag is all about, I told my friend emphatically, this is what it's all about.

Marcos Gonsalez (@MarcosSGonsalez) is an essayist, author, and assistant professor of English. Gonsalez's research interests focus on queer and trans Latinx aesthetics and cultural production. His current research project examines how scenes of queer and trans Latinx indolence, those moments of pleasurable leisure, refusals of labor, and avoidance of pain, challenge and reimagine oppressive logics tied to neoliberal capitalism and anti-queer/trans of color oppression. Alongside this primary research project, they are also working on a nonfiction project under contract with Beacon Press/Penguin, which analyzes the radical necessity and emancipatory energies of queer/trans Latinx nightlife in places like New York City, Miami, Los Angeles, San Juan, and Mexico City. His articles and essays can be found or are forthcoming at Transgender Studies Quarterly, ASAP/Journal, BOMB Magazine, Los Angeles Review of Books, Public Books, Literary Hub,and New Inquiry. He lives in New York City.

References

- Susan Sontag, "Notes on 'Camp,"" Sontag: Essays of the 1960s & 70s (New York: The Library of America, 2013), 270.[⤒]

- Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012), 185, 188.[⤒]

- Gabe Bergado, "Crystal Methyd Proves There's No One Way To Be Latinx." Nylon, October 2020. https://www.nylon.com/entertainment/crystal-methyd-on-drag-race-and-latinx-heritage.[⤒]

- Lawrence La Fountain-Stokes, Translocas: The Politics of Puerto Rican Drag and Trans Performance (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2021), 49.[⤒]

- Crystal Methyd, Instagram Post, March 20, 2021. https://www.instagram.com/reel/CMphjtaJv2-/?igshid=MDJmNzVkMjY%3D.[⤒]

- Crystal Methyd, Instagram Post, March 19, 2021. https://www.instagram.com/reel/CMm5uE3JroF/?igshid=MDJmNzVkMjY%3D. [⤒]

- Matt Kugelman, "Bianca Del Rio Snatch Game Audition: Dora The Explorer!" Youtube, June 17, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Lo6WIiDcrw.[⤒]

- Deborah Paredez, Selenidad: Selena, Latinos, and the Performance of Memory (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), 183.[⤒]

- BUILD SERIES, "Countdown to the Crown: Crystal Methyd," YouTube, May 29, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8GNjP7bWI9k.[⤒]