John Keene

***

"In the mark event, you enter your signature."

So begins Seismosis, John Keene's 2006 book of poetry, published as a collaboration with the artist Christopher Stackhouse. The quoted line is the first poem, entitled "Process," in its entirety. For a reader familiar with capital-T Theory, the sentence may sound weirdly familiar. While it's not a quote pulled directly from another source, it uses three major keywords, two titular, that appear in Jacques Derrida's well-known essay "Signature Event Context." The "mark event," in Seismosis's case, shuttles between being both the act of writing or drawing (the event in which a mark is made) and an identifying moment (the event in which one is marked). In both cases, a "signature" is entered: itself a paradoxical form of mark that is at once absolutely original and, like all other forms of communication, infinitely iterable. The entering of the signature is the "Process" that defines the event, making the "mark event" itself — as identifying or as writing process — also at once highly individual and beholden to the communicability of language. In a sense, this is a complicated way of describing the problem that dogs all creative writing: writing that is supposed to bear the mark of individual authorial genius, while being recognizable as creative writing, also falls into this or that tradition or community of practice. What to do, then, when you're in some sense suspicious of both?

I'm going to argue that Seismosis navigates precisely this tricky state of affairs — but it's important to note from the outset that Keene's work is not outwardly contrarian. Indeed, he is one of this century's greatest embracers, a fact brought very much to the fore by the range and breadth of his most recent book of poems, Punks (The Song Cave, 2021). A series of discrete shorter collections, many of which are startlingly forthright in their experiential narrativity, Punks looks almost nothing like the deeply abstract and heady Seismosis, but both cast an eye on the world that is, even at its most melancholic, generous and loving in the extreme. The earlier book continues to capture my interest because it struggles with something that Punks seems to have almost completely overcome: how to write about oneself as marked and marking. Punks is a book that revels in the queer Black body, in its historical inheritance, its music and tragedy and ongoing joy. Seismosis barely has a body at all.

What, to put it as bluntly as possible, is the deal here? Both readily available answers are wrong: Seismosis is not a book that wants to disavow "the mark event" that enters it into community with other racialized writers, nor is it a book that's secretly consonant with the type of writing we find in Punks. At its heart, the book is essentially an analytical project: the poems in Seismosis engage, at varying levels of obliqueness, with Christopher Stackhouse's drawings, themselves extremely abstract. The keywords toward which Keene gravitates — subjectivity, sign/signify, margin, positionality, mark — form a poetic "aboutness" that finds affiliation not with (as Timothy Yu has put it) "those neglected stories that some have asserted it is the job of minority literature to tell" but rather with the language used to analyze those stories.1 The foundation of Seismosis, in other words, is the language of scholarship.

This conception of the book's poetic method, already implied in its very title, imagines a sustained engagement with the specialized vocabulary of semiotics, using what are often seen as hegemonic textual frameworks towards radical aesthetic ends. This radicality is redoubled in the case of African American poetry because of how academic language, used as a stand-in for the university as a structure (or workplace), is often positioned as somehow inherently or fundamentally opposed not only to Black but also to poetic language, rendering it always already inappropriate to talk about it as either one, let alone both.2 But this is precisely what Seismosis asks us to do, in the process arguing that analytic abstraction can possess just as much force as narrative pathos in the quest for the expression of Black agency over and against the forces of white supremacy.

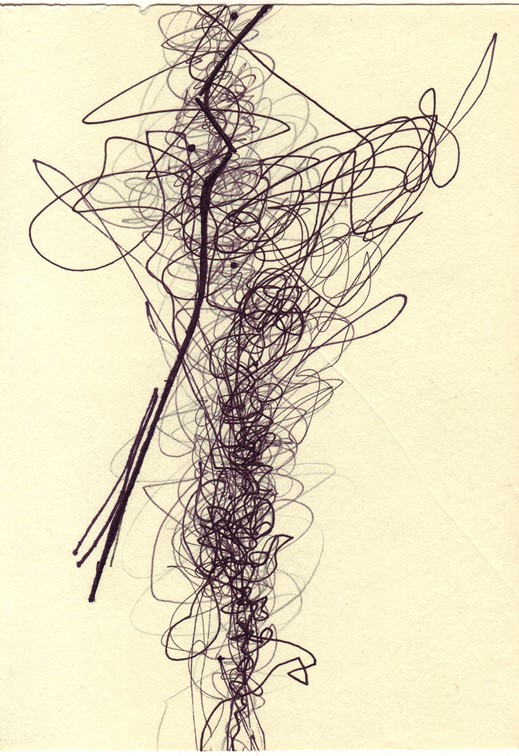

Keene's version of ekphrasis is, as he once put it to me, "a gesture against ekphrasis, in spite of the work itself. So, it's ekphrasis that is trying to disentangle itself from ekphrasis. Which is sort of crudely Derridean."3 What emerges from this conception is a meditative poesis that renders Stackhouse's scribbly, nearly anxiety-producing drawings (reminiscent in many cases of Cy Twombly's work) the departure points for, or perhaps the tangled counterpoint to, Keene's processes of disentanglement.In the discourse surrounding abstract art, Keene finds issues of marginality and access similar to those ones plaguing literary work that falls outside the boundaries erected for it by disciplinary history. In a type of dialectical response, Seismosis continually insists that a relatively disciplinary-specific language of critical analysis is not only appropriate in its application to Black literature, but is appropriate and generative in the literature itself. In a sense, the discursive lineage I am tracing is a familiar one that jumps the generic tracks at the end: it runs from Du Bois's ceaseless pursuit of a socio-historical theory of the "concept of race" through Gates's reworking of the play of signification and Spillers's excavations of an "American grammar" inseparable from the logics of enslavement directly (here's the jump) to the poetry itself: the vocabularies of Black theorization used to build an alternative literary mode.4

To return to the beginning, in "Process," the opening of the book is in its second-person address like the opening of a guest book, the event of which occasions the second event, and the second mark: that of signature, that which assures the presence of the source of an utterance even through its absence. What is Keene's signature? It is, if we are to use Derrida's formulation, both the singular mark attached to his presence (registered, of course, as non-presence because it is a substitution for the person whose signature it is), and the mark of writing that undoes the very concept of singularity by dint of its communicability or readability.5 All entries of signature, in other words, fail to represent a singular presence. The Derridian definition of signature is precisely a "mark event" which in fact refuses signature even as the event itself creates it. But "Process" only records the process by which the signature is entered. For its refusal, I'll turn to a poem entitled "Self."

"Self" is the only poem in Seismosis that explicitly mentions race. It begins with the line, in text slightly larger than that in the rest of the collection, "Self, black self, is there another label?*"6 The asterisk that follows the line precedes all the lines that follow it, making each subsequent line an annotation to the first inquiry; for example, "*In the mark, how does one identify authenticity or its inverse?" The last annotation, which is linked to the first poem by a keyword which does not appear in the intervening text, reads, "*In the end, refuse signature." It would be easy to read this line as falling into a kind of post-racial utopianism, carrying with it the idea that all one needs to do to find "another label" for a "black self" is simply to refuse the "mark event" of skin color. And it's true, to state it another way, that "Self" alone in Seismosis firmly identifies the speaking voice as attached to a body of color. But if the signature is the mark of individuality destroyed in its emergence by the fact of its iterability, it absolutely makes sense for a poetry such as Keene's to refuse it: it is precisely the idea of the narrativized Black self that a work such as Seismosis puts under erasure.

It does so by appealing to a kind of language that is not normally associated with the "signature" of the "Black self," but that is instead associated with the interpretation of how those selves appear and function in art and writing. There is nothing less (or more) "real" about this language, nor is there anything less (or more) realistic, but there is no appeal to realism. The first two notations to the first line of "Self" are illustrative:

*Raised to itself as a global agent, figure and ground impel representation.

*Does selving assign or resignify?7

These lines, combined with the seventh ("*Subjectivity: or is there another label?") form a neat packet of identity studies keywords: agent (and its relation, "agency"), representation, selving, (re)signify, subjectivity. There are more in other lines: "identity," "Other," "positionality." Words such as these often function in academic discourse as assemblages of syllabic building blocks, around which whole vocabularies of analysis are built. Take, for example, a passage that appears on the second page of Fred Moten's In the Break, on radical Black performance and performativity. Bringing together Saidiya Hartman and Judith Butler's work on alterity, he writes:

[a] critique of the subject animates Hartman's work. It bears the trace, therefore, of a movement . . . wherein the call to subjectivity is understood also as a call to subjection and subjugation and appeals for redress or protection . . . are always already embedded in the structure they would escape.8

The repetition of the prefix "sub-" forms a rhythmic alliteration, connecting the keywords "subject," "subjectivity," "subjection," and "subjugation," and stretching them over as well to "structure," forming a poetic rhythm of vocabulary that is not unlike the sibilant music of "does selving assign or resignify?" This is not to say that all criticism is somehow also poetic. It is, however, to point out that there is nothing less "authentic" about a poetry of analytical keywords than one of mimetic or experiential narrativity.

But of course there is also a strange type of mimesis at work in Seismosis. The poems may be highly abstract, but they're also somehow keenly and specifically observed, and they record a persistent intellectual questing after their own place in the poetic universe:

J: aura, or the lyrical-contemplative tendency

S: beyond its window, its shadow I am recoding9

In "Aura," of which these are the opening two lines, the poetic voice is presented dialogically, as a semi-exchange between "S" and "J." In the grammatical formulation of the first line, "aura" would seem to be defined by the phrase "the lyrical-contemplative tendency." Again, it is difficult to read the word "aura" and not immediately be transported into theory, this time that of Walter Benjamin and his ambivalent stance toward the "destruction" of art's aura by the processes of mechanical reproduction. And it is this term, which is also "the lyrical-contemplative tendency," that Keene is explicitly "recoding" in the opening lines of this poem. To recode aura is, to transpose a definition from Benjamin back onto the poem, to recode "authenticity" and "the ritual function" that adheres to received notions both of art's uniqueness and of its social purpose.10 To recode, importantly, is not to destroy but instead to repurpose, or (with apologies to actual programmers) to reprogram for use in another operating system. Keene recodes the "contemplative tendency" — which has resonances both with creative and with intellectual labor-practices, e.g. Wordsworth's oft-misread craft advice that poetry should only be written after its potential author had "thought long and deeply" about his powerful overflow of feelings.11 Even more aphoristically, one might think of the term "the life of the mind," here in an application that blurs the boundaries between "poetic" and "academic" contemplation, and further, that claims new territories of "authenticity" for the Black poet working on the margins.

In his work, then, Keene codes and recodes the "subaltern intellectual" whose practice roots itself firmly at the intersection of margin and center.12 A particularly forthright example of this aesthetic recoding can be found in "Analysis II." The poem is written in long couplets whose second lines are disjointed fragments about plate tectonics, and the first lines of which form a breathless treatise on the historical place of abstract art:

So we were talking about the idea and utility of distance, you know, and we got onto

the theory that the crust and upper mantle are broken between successive

how just before you perceive something as an identifiable object, indexed by the reality

felt as a rolling or rocking motion, more or less fluid, but constantly moving

in which you regularly live and function, your rods and cones capture it as something

retrograde, surface motion similar to the eyes at an approaching storm13

Almost all of the couplets work grammatically as units ("onto" goes into "the theory that," and "the reality" in the second stanza makes sense as a grammatical antecedent for "felt"), but break with each other as the reader moves down the page. What ties the poem together are those first lines of each couplet which, strung together, constitute a sort of run-on essay. Made into prose, these lines form a paragraph from which the following is excerpted:

Lyotard of course describes this in a slightly different but salient way, and it's this, I think, that abstract art really embodies, points to, approaches, not exactly the kind of ideal shape or form that Plato is talking about so much as another, anticipatory and shifting version the Dogon have described, though Kant's version is in there too . . .

The "this" in question is the pre-rational perception of the formless shapes and colors that we process in the instant before they congeal into "an identifiable object." Ultimately and collectively, the lines form a justification of sorts, one that explores the paradox of abstract art (and, by extension, abstract thought): on the one hand, "we conceive / . . . of abstract art as reductive," while on the other, we find it difficult to understand, difficult to find where the pleasure lies in observing it. What we have trouble doing, according to Keene, is "experiencing a more immediate pleasure beyond or outside instant mimetic / . . . recognition," a thought that explicitly draws upon Lyotard drawing upon Kant drawing upon Plato, but also and crucially adds the perceptual philosophy of the Dogon peoples of Mali, rupturing and then recoding the history of thought on the sublime, the abstract, and the "postmodern." The history of non- or anti-mimetic expression is reformulated as a total history, one that begins in "our earliest images, the kinds we find in the caves / . . . near Lusaka" and "through the Americas, Africa, and Asia." The language and art of abstraction, in other words, is framed as essentially part and parcel of the global aesthetic experience, one that has been subsumed under the need for mimetic narration as liberatory practice. The "idea and utility of distance" returns in this reframing as there for the taking all along in the poetic formulation of Black subjectivity.

Abstraction and analysis are linked in Keene's poetic practice by way of his experimental ("crudely Derridean") ekphrasis, one that uses a critical distance not usually associated with the "poetic" — much less associated with racialized poetics — to explore the limits of its own capacities. In the language and practice of citational coding, Keene finds a way to assert a radical poetics of Black subjectivity in which that subjectivity lays irrepressible claim to a mode of discourse typically considered to be outside the boundaries of its literary expression. Testing the limits of ekphrasis, and indeed of poetic expression more broadly, then, has less to do with what it can and cannot do than with who it has and has not typically contained. Keene's academic sensibilities, deeply ingrained by a life spent in and around universities and the para-academic structures that informed Black intellectual production in the latter part of the twentieth century, frame literary analytical vocabulary and grammars ("describe the means by which each concept aims to affect representation," from "Azimuth") as a radical means of expression capable of creating just as legitimate a form of Black poetic language as those languages more fully in line with canonical histories.14

In "Axioms," Keene writes: "What is visible: the sign enigma that punctures the tried idioms."15 He speaks here of his own work, of Stackhouse's enigmatic drawings, and of the theories of language — in which the sign is an endlessly receding enigma — that have helped him formulate this avant-garde poetry of thinking. Seismosis is made possible by a whole host of previous struggles and disciplinary developments that saw the rise, and then the establishment, both of creative writing and of ethnic and cultural studies in the American academy. Its break from the dominant aesthetic(s) espoused by both disciplines is performed in light of this fact, and talks back to it via methods of signification/signifyin(g) that Gates himself might well recognize as seriously playful reterritorialization. As in the phrase, woven through "Axioms" like the song refrain it is: "enigmatic signifier." The words do double duty: they both speak to how the poststructural signifier remains persistently mysterious, refusing to settle into the transcendental sign, and identify Keene himself as signifier. As signifier, Keene is both the one who signifies, and also the one who refuses to settle: and there's a lesson in that, for those of us who also depend upon the possibilities contained in the communities and codes (and recodes, and decodes) of critical analysis.

This essay is a modified excerpt from The Academic Avant-Garde: Poetry and the American University, available now from Johns Hopkins University Press and used with permission. You can order a copy of the book here.

Kimberly Quiogue Andrews (@kqandrews, @kqandrews.bsky.social) is a poet and literary critic. An American living in Canada, she is Associate Professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Ottawa.

References

- Yu, Timothy. Race and the Avant-Garde: Experimental and Asian American Poetry Since 1965 (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2009), 74.[⤒]

- In the longer text from which this piece is excerpted, I look at the way this dynamic plays out in the work of Melvin B. Tolson, a poet whose densely referential stylistics were received skeptically by his early readers.[⤒]

- John Keene in conversation with the author, December 2013.[⤒]

- These are all, of course, canonical prose texts: W. E. B. Du Bois, Dusk of Dawn (Oxford University Press, 2007); Henry Louis Gates Jr., The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of Afro-American Literary Criticism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988); and Hortense J. Spillers, "Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe: An American Grammar Book," Diacritics 17, no. 2 (1987): 65-81, https://doi.org/10.2307/464747.[⤒]

- Jacques Derrida, "Signature, Event, Context," in Limited Inc (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1988), 20.[⤒]

- John Keene and Christopher Stackhouse, Seismosis (Roanoke, VA: 1913 Press, 2006), 19.[⤒]

- Keene and Stackhouse, Seismosis, 19.[⤒]

- Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 2.[⤒]

- Keene and Stackhouse, Seismosis, 9.[⤒]

- Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 2011), 221, 224.[⤒]

- William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads, ed. R. L Brett and Alun R Jones (London; New York: Routledge, 2005), 291.[⤒]

- John Keene, "Gayatri Spivak & Anne Carson @ NYU," J's Theater blog (September 18, 2013), http://jstheater.blogspot.com/2013/09/gayatri-spivak-anne-carson-nyu.html. [⤒]

- Keene and Stackhouse, Seismosis, 56.[⤒]

- Keene and Stackhouse, Seismosis, 13.[⤒]

- Keene and Stackhouse, Seismosis, 94.[⤒]

Related reading

The Black Experimental Impulse: Returning to Seismosis

The Black Experimental Impulse: Returning to Seismosis

Sui Generis: On the Genius of John Keene

Sui Generis: On the Genius of John Keene

Unembodied Blackness and Social Critique: John Keene’s Annotations

Unembodied Blackness and Social Critique: John Keene’s Annotations

Mere Horizon: The Form of Desire in John Keene’s Poetics

Mere Horizon: The Form of Desire in John Keene’s Poetics

“A Leap into the Void”: A Conversation with John Keene

“A Leap into the Void”: A Conversation with John Keene

Passagens Estranhas: Translating the Obscene with Hilda Hilst and John Keene

Passagens Estranhas: Translating the Obscene with Hilda Hilst and John Keene

A Thank You Note

A Thank You Note

An Escaped Slave and a Good Person

An Escaped Slave and a Good Person

An Abstract Architecture: John Keene’s Counternarratives

An Abstract Architecture: John Keene’s Counternarratives

The Lover’s Complaint Concerning His Working Conditions

The Lover’s Complaint Concerning His Working Conditions

On Being Stuck at Customs: The Poems of Solmaz Sharif

On Being Stuck at Customs: The Poems of Solmaz Sharif