Asian/American (Anti-)Bodies

The Synaptic Poetics of Kimiko Hahn’s Brain Fever

In April 2015, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences published a study analyzing data culled from forty years worth of research on rat brains that produced a macro-level analysis of the cerebral cortex's neural networks. 1 Larry Swanson, corresponding author and professor at the University of Southern California, summarized the findings by proclaiming,

The cerebral cortex is like a mini-Internet. [...] The Internet has countless local area networks that then connect with larger, regional networks and ultimately with the backbone of the Internet. The brain operates in a similar way.2

If Swanson's words evince a striking yet unsurprising symmetry — people use computer networks to study brains, which are like computer networks — it's because the underlying metaphor of cognition as computation is so naturalized. And it is this ingrained relationship that Kimiko Hahn takes as her entrée to excavate language's relationship to thought in her most recent poetry collection Brain Fever (2014). The collection interlaces quotes from New York Times reportage on neuroscience with idiosyncratic lists in the zuihitsu3 style of The Pillow Book, Japanese poet Sei Shōnagon's observations and musings on her time spent in the Heian Palace. While Hahn's previous works also experiment with Japanese and Chinese poetics, Brain Fever's thematic departure from her earlier collections' focus on natural phenomena reveals a preoccupation with the mechanisms of racial thinking.

The term "brain fever" is often associated with the Victorian literature that portrayed it as a severe psychosomatic reaction to an emotional shock, experienced predominantly by women, and whose symptoms are a high fever and delirium. Today, brain fever has been mostly subsumed into the medical term encephalitis, a generalized description for inflammation of the brain. But a more recent referent of "brain fever" may be the critical frenzy surrounding all things brain or cognition. This development has been aptly dubbed "the neuroscientific turn" by Science, Technology, and Society (STS) scholars Melissa Littlefield and Jenell Johnson, who point out "the 'neuro,' (whether it refers to the brain or to neuroscience) is a historical object, created and shaped by inquiry."4

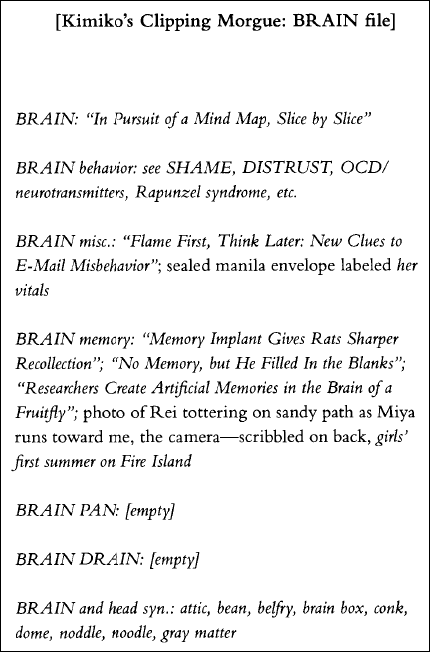

Brain Fever initially seems to conform to the classical computational model of cognition, the dominant paradigm of thought that views information processing sequentially and symbolically (analogous to computer data). The text opens with computer commands, invoking the digital encoding of memory:

Some entries are suspiciously "[empty]," while one is mysteriously marked "[file without label]: Spirit Photograph Exhibit/admit two, lavender lace thong, two flattened Chinese handcuffs" (6). Unlabeled, with no discernable organizing logic, this file's suggestive objects are less objects-in-themselves than an invitation for the reader to contemplate the synapses, or the minute gaps at the "junction between two neurons."5

The failure of the neat files-and-folders system to adequately capture or explain its objects is an early suggestion that Brain Fever is interested in what exceeds the classical model of cognition. Like the "[file without label]" filled with inscrutable detritus, the collection's poetic objects lack a fixed location or categorization. The explanatory gaps evoke the connectionist model of cognition, a competing paradigm that fell out of favor in the late 1960s. Connectionism's central argument — influenced by associationism à la David Hume — is that information is stored in between the units of neural networks, that is, among the synaptic connections themselves. In other words, in the connectionist model, information is not contained locally, but emerges from distributed patterns of recognition.6

If the classical model casts language as code, originating from a central processing unit — the brain — we may think of the classical model of racial thinking as a tautological paradigm that views racial expression as racial because it originates from a raced individual. By contrast, a connectionist paradigm that accounts for the spinal cord and the peripheral nervous system would suggest the production of race is distributed and contextual, without a fixed location. In addition, connectionism attends to memories, desires, and affects — felt information that exceeds a logic-based paradigm of knowledge. Race emerges not as a single, explanatory state, but as suspended between the multiple interpretations that shape gaps in language.

Focusing on the synapses, the collection reveals how the encoding of Asian/American racial difference as an essential foreignness constrains interpretive possibility. Throughout Brain Fever, this trope of foreignness is reworked on the metacognitive level — the poems first invite straightforward representational readings by deploying ostensibly Japanese/American language and objects, but then unsettle these interpretations to show the limitations of quick patterns of racial identification. Foreignness is instead incorporated as a formal element of the poems that shows meaning is not only encoded as individual units, but also through the epistemological framework language enters into. To make this point, Hahn uses words in multiple senses, and multiple senses are used to understand words. The collection's homophonic and homonymic wordplay creates multidirectional associations to articulate a vision of cognition that includes complex and seemingly inexplicable connections, cultivating what we might think of as a "synaptic poetics."

By denaturalizing systems of thought and knowledge that read Asian/American poetry only in terms of individual expression, Brain Fever poses a challenge to the classical model of racial thinking that assumes a synoptic subject. In the last line of "The Dream of a Little Occupied Japan Doll," the speaker concludes, "I've quit hoarding and now collect myself" (15). The double entendre of "collect" refers to gaining one's composure, but also to the act of assembling one's identity. Poetry and race's complex intersection should not be limited to the counting of raced subjects, but should include what poetry can tell us about how we read race. Hahn's work focuses racial form through the multidimensionality of linguistic construction. Recalling the original definition of the "aesthetic" as "the science of perception,"7 we can see that Brain Fever routes racial thinking through the coeval sensational networks of the connectionist model, not the linear representationalism of the classical.

*

A connectionist-inflected reading also shows how Brain Fever is able to resist being read in the utilitarian way in which so many gendered, racialized, queer, and disabled writers are read and consumed, where literature is reduced to evidence for sociological claims. The collection does so by insisting on the embodied nature of knowledge and thought. Hahn's 2012 poetics statement "Still Writing the Body" critiques "the West's anti-sensual bias — its fear and distrust of the flesh." In rejecting a view of the body and materiality as diametrically opposed to the "cerebral and conceptual," Brain Fever recognizes the neurological body as thinking, theory-making, and creative.8 A synaptic poetics re-members the body, limning an understanding of neuroscience that draws on the entire nervous system to disrupt both essentialized and disembodied conceptions of race.

The relation between brain and body changes each time that relation is conceptually accessed, and Hahn suggests that this connection is something like the indeterminate relationship between dreams and thinking. Are dreams thinking? The opposite of thinking? A certain type of thinking? These questions underpin the "dream" series of poems in Brain Fever, which all take as their intertext a November 10, 2009 New York Times article by Benedict Carey titled "A Dream Interpretation: Tuneups for the Brain."9 One researcher quoted in the piece, Dr. J. Allan Hobson, likens dreaming to background processing, arguing that "dreaming is a parallel state of consciousness that is continually running but normally suppressed during waking." But it is not Hobson that Brain Fever directly quotes — it is the response of another researcher, Dr. Rodolfo Llinás, who anonymously appears as "the researcher herself who believes," that "'dreaming is not a parallel state but consciousness itself / in the absence of the senses' input'" (23). The slide in language, as well as in gender, mirrors the instability of dreams and memories. In Llinás's formulation, dreaming is thinking, but the experience is shaped by the available sensory input. Dreaming's remove from the sensate world counterintuitively allows for a reconsideration of the distribution of the sensible in waking life, one that retains the multiplicity of meanings that Freud attributes to the dreamwork, which allows repressed forms to persist as long as they are denied.

The "dream" series, whose titles all follow the formula "The Dream of _____," dwells within objects, both natural and manmade: parsnips; bubbles; a pillow; a letter opener in the shape of a mermaid; knife, fork, and spoon; Shōji; a lacquer box; and a fire engine. These chance objects serve as points of departure through which Brain Fever takes punning's potentialities to the metacognitive level. "The Dream of Parsnips" uses visual punning to transform "a box of cigars" first into "dynamite" and then "the sudden squirming of earth worms" (23). Orderly objects with the potential of slow burn mutate into latent explosivity before transmogrifying into a wriggling, entangled mass.

Visual pattern recognition also provides the governing logic for "The Dream of a Fire Engine," where the titular fire engine's color acts as the principal-but-unnamed organizing concept — the poem's litany includes "Grandpa's ginger-colored hair, / Mother's lipstick, Daughter's manicure, / firecrackers, a monkey's ass, a cherry, Rei's lost elephant." While initially the individual objects are maintained as separate and distinct, the organizing logic—red—quickly subsumes the objects themselves. However, the poem's final line hides redness inside the body: "without warm blood a creature cannot dream" (30). Color is not just a superficial signifier, but one that circulates within. This reconfiguration mirrors the way in which race is first perceived visually as an external characteristic, but insidiously becomes an internalized one. The poem's (never explicitly mentioned) totalizing red-ness becomes a red herring, one that warns against the too-easy identification of superficial epistemological categories such as race.

"The Dream of Shōji" is one of two "dream" poems that addresses patterns of racial thinking by invoking explicitly "Japanese" subjects. The entirety of the short poem is as follows:

linen, cloud, cocoon, or albino?

How to say page or canvas or rice balls?

Trying to recall Japanese, I blank out:

it's clear I know forgetting. Mother, tell me

what to call that paper that slides the interior in? (28)

The poem deploys interlingual translation — Japanese and English — as well as intersemiotic — visual and written mediums. By simultaneously referencing two epistemologies of translation, the poem brings into relief the multiple ways in which language itself is understood. Reading the poem solely through the lens of foreign language acquisition ignores the intersemiotic translation at work, specifically, the morphological similarity of the poem's visually-punned objects. Taken as a list, the words/objects share neither an orthographic nor outward similarity as obvious as the red of "The Dream of a Fire Engine." This discontinuity allows the individual connections to come to the fore: "sand" and "snow" share a pale granularity, and both can be "sowed." "Linen," "cloud," "cocoon" have a white woven quality, explicitly named through "albino," although the last word carries an alarming, interruptive quality. While page and canvas share a functional and morphological similarity, the next list item, "rice balls," recursively wraps the line back around by doubling white granularity.

Hahn's evocation of visual punning inventively draws attention to the ways in which identity requires a foregrounding of resemblance. Racial logic also works from the outside in via perceived resemblance — "slid[ing] the interior in." In contrast, the poem's multidirectional readings require a studied assessment of what we read for. Would we ascribe any racial significance to rice balls without knowing the author's name is Kimiko Hahn? What weight do we give to white granularity, i.e. morphological similarity? Where do we factor in the racialized body of the author? "The Dream of Shōji" remains suspended between these nonconsilient paradigms of recognition. In addition, the poem stresses the centrality of the visual in epistemology—necessary to understanding morphological similarity—in order to highlight the embeddedness of race in the field of visual knowledge even in the absence of an identifiable racial subject. The poem's synaptic suspension of meaning both anticipates and makes visible how the reader's associative asymmetries and predilections are brought to bear.

Brain Fever's myriad dream objects, rather than belonging to a unified racial subject, are shown to be the means through which racialized subjectivity is formed.10 "The Dream of a Lacquer Box" immediately invokes japonisme. Lacquerware was at one point referred to as "japan," analogous to how porcelain is still commonly referred to as "china," and so a lacquer box is a uniquely Japanese object. The poem serves as a doubled container—for the box itself and for the speaker's longing. An excerpt of the poem shows the mix of desiderata:

like hairpins made of tortoiseshell or bone

though my braid was lopped off long ago,

like overpowering pine incense

or a talisman from a Kyoto shrine,

like a Hello Kitty diary-lock-and-key,

Hello Kitty stickers or candies,

a netsuke in the shape of a squid,

ticket stubs from A Double Suicide

[ . . . ] I wish I possessed my mother's

black lacquer box though in my dream it was red,

though I wish my heart were cóntent. (29)

By juxtaposing the wished-for Japanese box alongside contemporary commodity objects, the poem troubles any sort of easy historicity—the speaker's desire for familiarity suggests the melancholic objects are Japanese in feeling more than provenance. The inclusion of three Hello Kitty items sandwiched between "a talisman from a Kyoto shrine" and "a netsuke in the shape of a squid" (netsuke being small ornamental fasteners attached to men's kimonos) intersperses commodity culture among "authentic" Japanese things. These assembled objects show an intertwined relationship between people and things where the subject does not simply have objects. Instead, these fantasy objects are receptacles of memory and affect whose possession creates a dispersed consciousness, broaching the void signified by the speaker's longing. Even as Hello Kitty's iconic cartoon face separates her from the naturalistic images of "pine incense" and "squid," the repeating /k/ sound in "Kyoto," "Hello Kitty," "netsuke," "squid," and "ticket stubs" deploys a shifting resonance between the objects, including the /k/ of "lacquer." If the contents of the desired box are Japanese, the evolving /k/ sound suggests their Japanese-ness is not found in the same location or form, but both emerges from and exceeds their individual functions in the imagined collection. The poem indexes the failure of both physical and psychological containment, as marked by the double entendre (and final /k/ sound) of "content(s)."

The image of the imagined lacquer box is an apt souvenir of reading Brain Fever — the kaleidoscopic collection's insistence on the lack of singular explanations or meanings enjoins the reader to sense anew how language continually rewrites its biological subject at the moment of interpretation. Brain Fever cultivates an Asian/American subjectivity formed synaptically through the multiple senses of language, an oscillating process that will always resist final resolution.

Michelle N. Huang is a dual-degree Ph.D. candidate in the Departments of English and Women's, Gender, & Sexuality Studies at The Pennsylvania State University. Her research interests include Asian/American literature, posthumanism, and feminist science studies in twentieth and twenty-first century fiction. Michelle's articles are published or forthcoming from Twentieth-Century Literature and the Journal of Medical Humanities, and her book reviews have appeared in Configurations, Hypatia, and Graphic Medicine.

References

- I wish to thank Christopher T. Fan for the invitation to be a part of this series and for his editorial guidance; Sara DiCaglio, J. Ryan Marks, and Laura Vrana for discussing and reading drafts; and audience members of the "Writing 'Life' (III): Bio-, Neuro-, and Eco-poetics" panel at the 2015 Society for Literature, Science, and the Arts Conference for their insights and feedback.[⤒]

- Robert Perkins, "Cerebral cortex in rats' brains is set up like the Internet," USC News, April 6, 2015.[⤒]

- In an interview, Hahn states, "I like to think of the zuihitsu as a fungus—not plant or animal, but a species unto itself. The Japanese view it as a distinct genre, although its elements are difficult to pin down. There's no Western equivalent, though some people might wish to categorize it as a prose poem or an essay . . . some of its characteristics: a kind of randomness that is not really random, but a feeling of randomness; a pointed subjectivity that we don't normally associate with the essay. The zuihitsu can also resemble other Western forms: lists, journals. I've added emails to the mix. Fake emails." See Laurie Sheck, "Kimiko Hahn," BOMB 96 (Summer 2006): 52.[⤒]

- Melissa M. Littlefield and Jenell M. Johnson, eds., The Neuroscientific Turn: Transdisciplinarity in the Age of the Brain (Ann Arbor: U. Michigan Press, 2012), 8.[⤒]

- "synapse, n.", OED Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed December 9, 2015.[⤒]

- Connectionism was also sometimes referred to as parallel distributed processing (PDP). See Elizabeth Wilson's Neural Geographies: Feminism and the Microstructure of Cognition (New York: Routledge, 1998) for a genealogy of connectionism.[⤒]

- "aesthetic, n. and adj.", OED Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed December 9, 2015.[⤒]

- Kimiko Hahn, "Still Writing the Body," in Eleven More American Women Poets in the 21st Century: Poetics Across North America, eds. Claudia Rankine and Lisa Sewell (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2012), 109.[⤒]

- With the exception of "The Dream of a Raindrop."[⤒]

- As Christopher Bush argues, "the Japanese thing was not simply an example of the embodiment of a racial imaginary, but a site at which the logic of embodiment itself was worked through" (79). See "The Ethnicity of Things in America's Lacquered Age," Representations 99.1 (Summer 2007): 74-98.[⤒]