The Migrant’s Nervous Condition

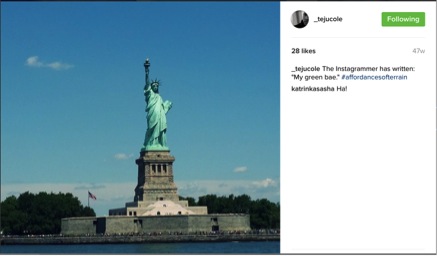

All photos from @_tejucole on Instagram

In August 2015, in the thick of Europe's migrant crisis, novelist, essayist, and photographer Teju Cole began to post image after image of the Statue of Liberty on his Instagram feed. Over a period of several days, he "regrammed" seventeen photographs and videos of the statue taken at different times of the day but largely from the same angle, all culled from the massive ad-hoc photographic archive that is Instagram. The effect, when viewing this series on Cole's feed, is immediate and stultifying. The sheer repetition of the overwrought symbol of "liberty" rendered into tiny squares—now swipeable, likable, shareable—raises many questions about monumental works in the age of digital reproducibility.[1] But scrolling through image after image of the statue also prompts the Instagram user to reconsider this emblem of welcoming to the world's weary migrants, particularly because it was posted at the same moment the surge of migrants to Europe's shores broke historical records. Through sheer force of repetition, Cole raises implicit questions about the state of contemporary global migration. What has changed since the Statue of Liberty was erected in 1886? What can this monument to the lofty concepts of "liberty" and universal safe harbor tell us about the current condition of global migrants?

The issues raised by Cole's repeated regramming of the Statue of Liberty are not new to his larger body of work; indeed, they seem to pick up where his 2011 novel, Open City, left off. Set in 2006, Open City follows its Nigerian immigrant protagonist, Julius, as he wanders through the streets of Manhattan and Brussels in a pensive kind of flânerie. A well-to-do psychiatrist practicing at Columbia University, Julius meditates on conversations with patients and friends who seem to suffer more from historical traumas than personal ones. All the while, he contemplates the ambivalent histories of New York's most famous monuments. The Statue of Liberty crops up in Julius's thoughts and vision more than once in the novel, always managing to stoke a degree of existential malaise. Cole strategically places Julius's first encounter with the statue near the novel's midpoint, after he has returned from an unsettling trip to Brussels. An impromptu and provocative dialogue with two disenfranchised Moroccan immigrants there disturbs Julius's perception of immigrant life in Western Europe and the United States, and his unease does not dissipate back in New York.

Upon his return, an outsized reaction to a seemingly minor incident—forgetting his ATM PIN at a bank near Wall Street before meeting his tax attorney—betrays a sense of instability in his own status as a migrant underneath his well-heeled cosmopolitan exterior. It is directly after this that he catches a glimpse of the Statue of Liberty in the distance, and his mind immediately turns to the sordid and violent histories of the financial district. He ponders at length on the acquisition of capital that transformed nineteenth-century Manhattan into the financial powerhouse it continues to be, largely supplied by massively profitable investments the City Bank of New York made in slave ship construction and Caribbean sugar plantations after the chattel slave trade had been outlawed in the Union. The associations in Julius's stream of consciousness implicitly draw connections between all that the statue symbolizes and the humanitarian crimes that mark much of American history. Profoundly unsettled, Julius reflects that he feels himself to be "subject to a nervous condition," an uncommon phrase to describe bewilderment, and indeed, one with a powerful postcolonial resonance (Cole 161).

The "nervous condition" Julius alludes to is Cole's explicit nod to Jean-Paul Sartre's introduction of Frantz Fanon's seminal text, The Wretched of the Earth. Summarizing Fanon, Sartre writes, "The status of the 'native' is a nervous condition introduced and maintained by the settler among colonized people with their consent." [2] This phrase, of course, also inspired the title of Tsitsi Dangarembga's 1988 coming-of-age novel, Nervous Conditions, in which two young Zimbabwean women experience the turbulent emotional consequences of colonial "double-consciousness."[3] In describing his state of mind as a "nervous condition" in Open City, Julius conjures the specter of the traumatized colonized subject. The conditions that surround this moment of confusion, however, are hardly those of one subjugated under an oppressive imperial regime. Julius is a free, mobile, and moneyed individual—half Nigerian, half German, and fully cosmopolitan. He is many steps into the postcolonial present, and away from the political exigencies of Fanon's era. Why, then, does the neurosis of the colonized flare up as he performs banal bureaucratic duties in Lower Manhattan, in the shadow of the Statue of Liberty? Cole's return to the Statue of Liberty as both a literary and visual motif may offer some insight into Julius's "nervous condition."

Julius's crisis in this moment is not precipitated by the cliché immigrant dilemma of hybrid identities (is he American? Nigerian? Both?), but the predicament of identifying either as a member of the historically oppressed or the historically triumphant. His crisis while preparing to perform the civic duty of filing his taxes is one of profound ethical consequences—whether he understands himself to be an example of modernity's failures or successes. In this moment, he does not know whether he has more in common with those captured and enslaved on the West coast of Africa or with the profiteers of slavery who laid out the groundwork for American capitalism.

The very last thoughts Julius has before the narrative ends are of the Statue of Liberty itself. Appropriate to the tone of the novel, Open City ends with no comment on the monument's overwrought public symbolism, but instead a meditation upon a little-known yet gruesome curiosity about the statue:

Although it has had its symbolic value right from the beginning, until 1902, it was a working lighthouse, the biggest in the country. In those days, the flame that shone from the torch guided ships into Manhattan's harbor; that same light, especially in bad weather, fatally disoriented birds. The birds, many of which were clever enough to dodge the cluster of skyscrapers in the city, somehow lost their bearings when faced with a single monumental flame (Cole 258).

The metaphor is as transparent as it is astonishing. The very same light which directed foreign vessels toward American shores in a magnanimous gesture of welcoming so blinded thousands of birds as to drive them off their course of migration, and more troublingly, to meet violent deaths by slamming against the monument to immigration itself. The statue's inexplicable bird mortality rate is a rich metonym of the grand American experiment's collateral damage and echoes the tension between the statue's sculptural form and the poem carved at its base.

*

As a monument to American civic ideals as well as one of magnanimous welcome to the world's variegated migrants, the Statue of Liberty itself seems to suffer from the very sort of identity crisis that migrants and their progeny face upon arriving and settling in the United States. It appears to relay competing messages: one of universalist ideas of freedom, and the other of universal safe harbor, two notions that are quite often in conflict with each other. The statue stands, of course, squarely upon the traditional border of the United States in a liminal space of transition—between "over there" and "here," between "us" and "them." The sculpture, designed and built by Frédéric Bartholdi and Gustave Eiffel, was not gifted to the U.S. by France in 1886 to celebrate our status as a "nation of immigrants," but instead our shared values of republicanism: liberty, equality, fraternity (more "Unum" than "Pluribus"). In its French-sculpted form, the Statue of Liberty symbolizes the triumph of the assimilated immigrant who subscribes entirely to the Enlightenment ideas of universalism.

But it is actually the poem carved at the statue's base, rather than the sculptural form itself, that imparts the symbolic notion of the United States as a space of welcome for spurned and exiled souls from lands afar. It is only in Emma Lazarus's "The New Colossus," inscribed seventeen years after the statue was initially dedicated, that Lady Liberty embraces the world's tired and poor. Due also to the statue's location on Ellis Island, the first port of entry for so many immigrants coming from across the Atlantic, the message of refuge and welcoming to weary migrants has outsized that of republicanism. And in the context of immigration, the loftiness of republican "liberty, fraternity, and equality" belies the thornier aspect of coming to America: adherence to its ideological systems. The difference between the poem and the statue is the difference between the migrant and the immigrant—that is, the difference between arriving here from inhospitable circumstances and settling into to the values of universalism.

Most Americans are only familiar with the most famous and over-quoted lines from "The New Colossus." But upon considering it in full, one sees a marked repudiation of the old world, wrapped up as it is in legacies of antiquity and "storied pomp." Deeming Lady Liberty the "Mother of Exiles," "The New Colossus" ventriloquizes the statue and calls out to the outcasts of Europe. Indeed, in the poem, the statue addresses Europe directly, requesting, along with the "huddled masses yearning to breathe free" that the continent send "the wretched refuse of your teeming shore/ Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me." There is something shockingly subversive about the perspective Lazarus gives the monument, at once dismissing Europe's pomposity (and gift-giving France along with it, of course), and also undoing any notion of American exceptionalism. "This is the entry point to the Earth the meek have inherited," the poem seems to say. Thus the poem engraved at the bottom of the Statue of Liberty receives not just any kind of migrant; it welcomes specifically those whom Europe has rejected. That is, it is directed at nationless refugees. "The New Colossus" includes no celebration of republicanism, no prompt to assimilate to universalist ideals, no mention of liberty whatsoever. Lazarus's maternal vision of this monument offers only safe harbor and refuge to those the rest of the world has failed. Together the poem and statue seem to mimic the trajectory of the disenfranchised migrant or refugee who enters at the bottom echelons of society and eventually ascends to something else entirely: the exemplary model of the immigrant who has successfully embodied universalist ideals.

*

The identity of the refugee is markedly different from that of the immigrant wishing to assimilate. Hannah Arendt, after the atrocities of WWII, began her essay entitled, "We, Refugees" with the straightforward statement: "In the first place, we don't like to be called 'refugees'" (Arendt 111). The "we" of the essay is, of course, European Jews who have escaped the possibility of extermination. "A refugee," she writes, "used to be a person driven to seek refuge because of some act committed or some political opinion held....Now 'refugees' are those of us who have been so unfortunate as to arrive in a new country without means and have to be helped by Refugee Committees" (111). In that essay, Arendt refers specifically to the attempt of persecuted German Jews to make lives for themselves in other European countries by whole-heartedly embracing the prompt to assimilate into, say, French culture, rather than remain bound to the one that has ousted them. To cling to the identity of the former homeland, and moreover to cling the identity of having been rejected from the former homeland, becomes a dangerous choice in the modern world.

It is true that most of us depend entirely upon social standards....we are—and always were—ready to pay any price in order to be accepted by society. But it is equally true that the very few among us who have tried to get along without all these tricks and jokes of adjustment and assimilation have paid a much higher price than they could afford (Arendt 118-119).

Arendt suggests that "refuge" is really only possible if the refugee immediately renounces the title and its attendant history and chooses immediately to conform to the identity of an "immigrant," whose aim logically is to assimilate.

This protocol is certainly all the more palpable in Western Europe nations, which, unlike the United States, have no foundational mythos of being constituted from heterogeneous migrants. As Arendt states, veering from the aspiration of becoming seamlessly "French" or "British" after migrating can have dire consequences. To maintain the marks of the journey, to fully inhabit the status of "refugee" rather than "immigrant," is really to preserve the particularities of individual histories, and moreover, individual traumas. To assimilate is to "move on," as it were, or more precisely, to repress. And this idea, this call to conform, which Arendt writes about in reference to mid-twentieth century Western Europe with a degree of anguish, seems to resound quite loudly in current political discourse surrounding immigration in both Europe and the United States alike. The sentiments of the poem are now trumped by the loftier values that the statue itself was originally meant to represent: Enlightenment ideals of republicanism and universality, with the caveat that there is only one model for a universal subject, which looks a great deal more like a strapping, triumphant Greco-Roman quasi-Colossus than a poor, tempest-weary migrant.

The conflict between the two figures of migration Arendt gestures toward—the disenfranchised refugee and the assimilation-seeking migrant—is embodied in the competing messages the statue appears to issue. On the one hand, the triumphant stance of the statue functions as a prompt to embrace the universalist values it symbolizes. On the other hand, Lazarus's poem addresses potential Americans as refuge-seekers before anything else. The poem and the statue seem to index two distinct channels of migration whose cross-contamination is far more unsettling than a cheerful, Instagrammable reproduction of the statue-as-monolith might allow us to perceive. By repetitively regramming tourist snaps of the statue unwittingly taken at similar angles and times of day, Cole highlights the uncanny place of the monument in the American symbolic lexicon. We know it means something important to us, but as soon as we attempt to articulate what that something may be, we reach an impasse.

*

The tension between the disenfranchised refugee and the assimilated immigrant crystalized in the very form of the Statue of Liberty is thoroughly explored in Zia Haider Rahman's 2014 novel, In the Light of What We Know. Rahman's novel has been compared by numerous reviewers to Open City, and indeed, both texts bear many important similarities. In the Light of What We Know also follows an itinerant intellectual protagonist from the Global South who moves through the elite echelons of western society, contemplating how, exactly, we got here ("here" being the neoliberal, postcolonial, post 9/11 world). But unlike Julius's privileged Nigerian childhood experiences with drivers and boarding schools, Rahman's Zafar comes from the working class milieu of London's Bangladeshi community. Zafar's prose simmers with ressentiment as he relates his life story to his friend, the novel's unnamed narrator. Bootstrapping his way into Oxford's elite circles and on into the international circuit of NGO and humanitarian work, he finds the class hierarchies and etiquette of high British society to be insidious at best and violent at worst. Much more so than Julius, for Zafar the aim of success in British society is an explicit goal, and his practice of hiding and denying his past and excising his origins is extremely methodical. He resembles the refugees in Arendt's formulation—those who are "ready to pay any price in order to be accepted by society."

Rahman gives Zafar ample space to imagine what his life would have been like if he and his family had arrived on American rather than British shores as a young boy from Bangladesh. In the States, he feels that "the information that my father was a waiter, my mother a seamstress, and the response would be utterly different" than in England (Rahman 135). The comparison is revelatory and somewhat troubling. His vision of immigration to the United States is idealistic to a point that borders on fanaticism. Zafar explains to the narrator:

I love America for an idea. The reality is important but ambiguous. In Senegal, there stands a building where slaves were stored before they were sent on to the New World. It was built in the same year as the American Declaration of Independence. I love America for the clear idea behind the cloudy reality....It is the idea of hope, that grand, audacious idea that makes the Britisher blush with embarrassment. I love her for her thought, first, of where you're going, not where you're from; for her majestic optimism against the gray resistances of Europe, most pure in Britain (Rahman 19-20).

Zafar's idealization of the way America receives its migrants is curious insofar as he does not seem blind to the atrocities that belie the message of "audacious hope," as it were.[4] He does not seem to be disturbed, the way Julius is, by the mass systematized violence that underpin the successes of American experiment. He seems, rather, to value the American ideal all the more because of its internal paradoxes. The "clear idea," the very concept of America, means more to him than the damage wrought in the pursuit of executing it.

Zafar, too, muses upon the fraught symbolism of the Statue of Liberty. The narrator recalls a joint trip to New York during which Zafar expressed with zealotry his admiration for the United States. On a spontaneous jaunt to Ellis Island, Zafar marvels at Lazarus's words: "'Mother of Exiles.'...She's pleading on behalf of the poor and the meek, for they shall inherit the New World if not the Old" (99). Zafar wants desperately to be validated as a refugee, despite the accomplishment of becoming a fully "assimilated" member of elite English and cosmopolitan society. For Zafar, the messages of Lazarus's poem and Bartholdi and Eiffel's statue are not in conflict but on a continuum. His full subscription to the narrative crystallized in the statue and its poem (despite never being a U.S. citizen himself) raises very important questions about the stakes of contemporary migration and immigration. What America allows for, according to his logic, is the option of simultaneously identifying as the oppressor and oppressed. Fully inhabiting this contradictory stance is what creates a kind of cosmopolitanism that requires no obfuscation of origins.

Yet Zafar also seems, by proxy, to be caught in a kind of immigrant Oedipal drama, desiring the "Mother of Exiles" while simultaneously reveling in the destruction of the phallic symbols of American capitalist hegemony. He brashly declares early in the novel: "Before 9/11, I was invisible, unsexed. How is it that after 9/11 suddenly I was...attractive?... Was this person among us no longer the meek Indian, the meek Pakistani, the sepoy, but fully man? Before 9/11, I was hidden behind the wall of colonial guilt after having been emasculated by a history of subjugation" (20). Zafar believes he has been able to transcend the identity of an emasculated colonial subject through the Islamic potency lent to him by the gruesome spectacle of 9/11. He posits the event as a sort of violent retribution for centuries of colonization—a global practice of domination rooted in systems of subjugation far more complex than simply class inequity.

In constructing Zafar's personal history, Rahman reveals a great deal about the troubling matrix of allegiances and emotions that constitute the subjectivity of a contemporary global immigrant. He is exemplary of the contemporary globally southern cosmopolitan subject, crystallizing the massive accretion of the historical and geographic contingencies which make possible radically contradictory political stances and desires—the sort who can praise the wild optimism of American exceptionalism with full knowledge of its genocidal past. Zafar maintains a troubling capacity to sing the praises of American "audacity" and "hope" before the Statue of Liberty while simultaneously drawing a perverse sense of virility from the destruction of the symbols of American finance capital. All the while, he demonstrates none of the ambivalence nor the "nervous condition" Julius suffers. To the contrary, Zafar sees the destruction of the symbols of capital to be the most potent expression of modernity, a logical continuation of the narrative that produced the statue's inherent contradictions.

In Open City, Julius cannot seem to fully and willfully inhabit and celebrate the paradox of migration and immigration to America the way Zafar does. He finds himself again and again circling back to the financial district of Lower Manhattan, returning what was then still Ground Zero, as though mired in a repetition compulsion. As he contemplates the recent violence of 9/11, his tone is decidedly more somber than the excitable Zafar. Nearby he encounters a plaque which reveals that the surrounding spaces of Battery Park served as slave burial grounds in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

It was here, on the outskirts of the city at the time, north of Wall Street and so outside civilization as it was then defined, that blacks were allowed to bury their dead. Then the dead returned when, in 1991, construction of a building on Broadway and Duane brought human remains to the surface. They had been buried in white shrouds. The coffins that were discovered, some four hundred of them, were almost all found to have been oriented toward the east (Cole 221).

These breathtaking details imply an epochal reckoning in 9/11 that is far more profound than Zafar's feelings of sudden potency afterwards. The evidence of specific burial rituals—white shrouds, heads facing East—mark these dead as Muslim. Completing the historical circle Cole sets up here is disquieting, to say the least. Open City reminds us, through the searching rambles Julius takes in the city and across the world, that the first mass wave of migrants did not arrive from Europe as emigrants, or even refugees, but as slaves. And upon migrating they were not only stripped of their cultural heritage, but more importantly, they were stripped of their very humanity.

The sweeping project of "E Pluribus Unum" is thoroughly pocked with violences both grand and small, more often silenced than not. Julius's rambles through New York unearth these violences while provoking the quandary of his own complicity in the same historical traumas that devastated his ancestors. His rumination on the monuments and spaces that have accrued significance in America's self-narratization gesture towards the idea that rather than universalism as such, the universal condition of the migrant is to find oneself precariously positioned within these histories of violence.

The hordes of refugees and of migrants who arrived on American's shores in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries hoping for a better life have been given a distinct place in the narrative of the American dream, the hope of universalism. The African slaves who were subjugated and Native Americans who were eliminated have a comparatively minuscule role in the grand narrative of United States history. Even Lazarus's poem, which calls out to the world's poor and wretched, includes no plea for the African migrants who arrived centuries ago but were never truly granted the option of full assimilation. Julius's "nervous condition" results from a moment of clarity in which he sees the danger of attempting to assimilate to a society that was founded upon global acts of violence. His neurosis comes not simply from recognizing his own consent in being oppressed, but rather in seeing himself as an agent in violent oppression. His assimilation into the elite echelons of American and cosmopolitan society is predicated upon an unspoken complicity—if not participation—in that historical violence. Zafar, on the other hand, rather than suffering from a "nervous condition" veers into the territory of a global Stockholm Syndrome, reveling in a perverse identification with the perpetrators of massive violence, whether they are America or Al-Qaeda. Though "The New Colossus" urges Europe to keep its "storied pomp," American pomposity takes on its own idiosyncrasies.

Cole's experiment in regramming the Statue of Liberty last summer, if nothing else, demonstrates that the mass repetition of its image does away with the inherent contradictions in what the statue actually offers to incoming migrants. Indeed, placed upon the pedestal of Lazarus's poem, the Statue of Liberty stands in a gestalt of ambivalence. And in both Cole's and Rahman's literary (rather than visual) engagements with the Statue of Liberty, we begin to see how the simultaneous offer of refuge and the prompt to assimilate are quite often at disturbing odds with each other. In our contemporary moment, when the political world that informed Fanon's configurations of colonizers and natives has taken on a different form, it is now the migrant who is subject to a nervous condition.

Nasia Anam received her Ph.D. in Comparative Literature at UCLA and is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor of English at Williams College. Her writing and reviews have appeared in Interventions, Verge: Studies in Global Asias, South Asian History and Culture, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Aerogram.

[1] Part of Cole's project in regramming the statue ad nauseum was, no doubt, to press even harder upon Walter Benjamin's mid-twentieth century notion that the work of art has lost its "aura," or uniqueness, in modernity. Of the many qualifications of "aura" in "A Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility," Benjamin deems it "a strange tissue of space and time: the unique apparition of distance, however near it may be." He argues that in the age of film, "aura" is in a state of decay, propelled by "the desire of the present-day masses to 'get closer' to things, and their equally passionate concern for overcoming each thing's uniqueness...by assimilating it as a reproduction" (Benjamin 254).

[2] It should be noted that in the original French, Sartre uses the term "névrose" as a noun to describe "l'indigénat." "Nervous condition," a term that has much currency in postcolonial scholarly discourse, comes from Constance Farrington's 1963 translation into English ("The status of the 'native' is a nervous condition introduced and maintained by the settler among colonized people with their consent" [20, Preface to Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington, 1963]). Richard Philcox's 2004 translation forgoes this term for one with more contemporary medical and diagnostic valences that perhaps "nervous condition" does not: "neurosis." It is as follows: "The status of the 'native' is a neurosis introduced and maintained by the colonist in the colonized with their consent" (Preface iv, Richard Philcox, 2004).

[3] With reference to the concept of "double-consciousness" first outlined in the 1903 essay, "The Souls of Black Folk," in which W.E.B. Dubois limns the "peculiar sensation...of always looking at one's self through the eyes of others, of measuring one's soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity" (7). In 1993 Paul Gilroy's The Black Atlantic further expanded this notion by viewing modernity (and modern subjectivity) as such through the lens of "double-consciousness," incorporating the multivalent cultural, social, and historical ramifications of the transatlantic slave trade and colonial hegemony.

[4] Zafar no doubt references the title of Barak Obama's similarly titled book, published two years before his inauguration as the first African American president of the United States.

Works Cited

Arendt, Hannah, and Ron H. Feldman. "We, Refugees." The Jew as Pariah: Jewish Identity and Politics in the Modern Age. New York: Grove Press, 1978, 55-66.

Benjamin, Walter W, and Howard Eiland. "A Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility." Selected Writings: Vol. 4. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 2003, 251-258.

Cole, Teju. Open City: A Novel. New York: Random House, 2011.

Dubois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso, 1995.

Lazarus, Emma. "The New Colossus. Selected Poems. New York: Library of America, 2005, 58.

Rahman, Zia H. In the Light of What We Know: A Novel. , 2014.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. "Preface." The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove, 2004, 11-31.