Trash to Treasure: Cover Songs and Hipster Redemption

Britney Spears is just trailer trash.

—Stephen King, Time Magazine

"Notice me," Britney Spears pleads in her 2004 ballad "Everytime," then asks, "Why carry on without me?" At first listen, the song is quite obviously a meditation on celebrity narcissism. Written by Spears herself (at a piano, during a "detox retreat" on Italy's Lake Como), it has been largely assumed — an assumption the music video and Spears' subsequent interviews support — the song is a reaction to Justin Timberlake's 2002 hit "Cry Me a River," from his debut solo album following the disbanding of N*Sync, which he recorded after the implosion of his four-year relationship with Spears. It was the end of a pop music power couple, and both parties capitalized on the breakup with hit singles.

Spears' performance of "Everytime" has been described as trite, overly breathy, bubblegum pop. Even in reviews that seem to favor In the Zone, Spears' fourth studio album, which includes "Everytime," the ballad stands out as an anomaly; in a review for Entertainment Weekly, David Browne explains that "with its dainty piano, 'Everytime' plays like a forlorn postmortem on her Justin Timberlake era. Even here, Spears suffers by comparison with Timberlake, who always sounds as if he's communicating directly to the listener." This essay examines the reception of Spears' "Everytime" as trash, and how the song is "redeemed" by indie-darling Glen Hansard's cover of it: an acoustic, aesthetically hipster recording that appeared on the charity album Even Better than the Real Thing (Vol. 2, 2004) and gained worldwide circulation via YouTube and iTunes. This "redemption" of a trashy pop song comes at a great cost. I ask: who is able to redeem "diva trash"? My hypothesis: white men, such as Glen Hansard, viewed as universally "authentic," un-raced, un-gendered hipsters.

My research into the aesthetics and politics of hipster culture assumes that much of what makes a text "hip" is the author's ability to redeem — most often through irony and one's cachet of cultural capital — a text from low to some higher cultural form. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, we have seen numerous examples of this; in fashion, trucker hats and "wife-beater" tank tops became en vogue; in drink, PBR, a decidedly blue-collar beer, could be seen in the hands of hip twenty- and thirty-somethings from Brooklyn to Silver Lake. And in music, the ironic cover song became a staple of hip musicians, from Sufjan Stevens to Ben Folds to Hansard himself. To this end it appears that hipsters — largely white, college-educated, cis-gendered men — buy cultural capital by positing themselves as a post-racial, post-gender group (see, for example, their borrowing of "Arab" kafiyas or "women's" skinny jeans); the truth, however, seems to be that these hipsters "redeem" these various texts by making them, in fact, white, male, and of a certain socio-economic class often far removed from each object's origins. Thus I wonder, How does Hansard redeem Spears' "Everytime?" He does this by marrying his own lionized hipster authenticity — or white male universality — to her song, performing the cover with a simultaneous sense of both irony and genuine emotional affect.

Hipster texts are most concerned with a sense of authenticity, and much of this authenticity derives from the text's author, or, in the case of Hansard, remixer. Thus, a brief consideration of the biographies of both Spears and Hansard, framed in terms of hipster aesthetics, becomes necessary. Not surprisingly, Spears' biography reflects not hipster stardom, but the diva's ascendancy to power, marked time and time again by a sense of artificiality. Born in rural Mississippi to two working class parents, Spears grew up in Kentwood, Louisiana; though her origin story definitely denotes a "white trash" authenticity, valued amongst hipsters, this authenticity is lost in the blatant grab for stardom that marks Spears from an early age. At ten, she appeared on Star Search, and at twelve, began her stint as a Disney darling on The New Mickey Mouse Club alongside future rival diva Christina Aguilera and future beau Justin Timberlake, as well as JC Chasez, Ryan Gosling, and Keri Russell. Rolling Stone aptly describes the next transition in Spears life-career:

A former child actress...Spears early on cultivated a mixture of innocence and experience that generated lots of cash. Her first single, " . . . Baby One More Time," paired a vaguely S&M lyric (the ellipse follows the words "Hit me") with a fluffy, Europop-style big beat, and a video in which the singer paraded around in a Catholic schoolgirl outfit. Released in late 1998, it went to Number One, and the album of the same name, issued in January 1999, followed suit, debuting in the top spot.1

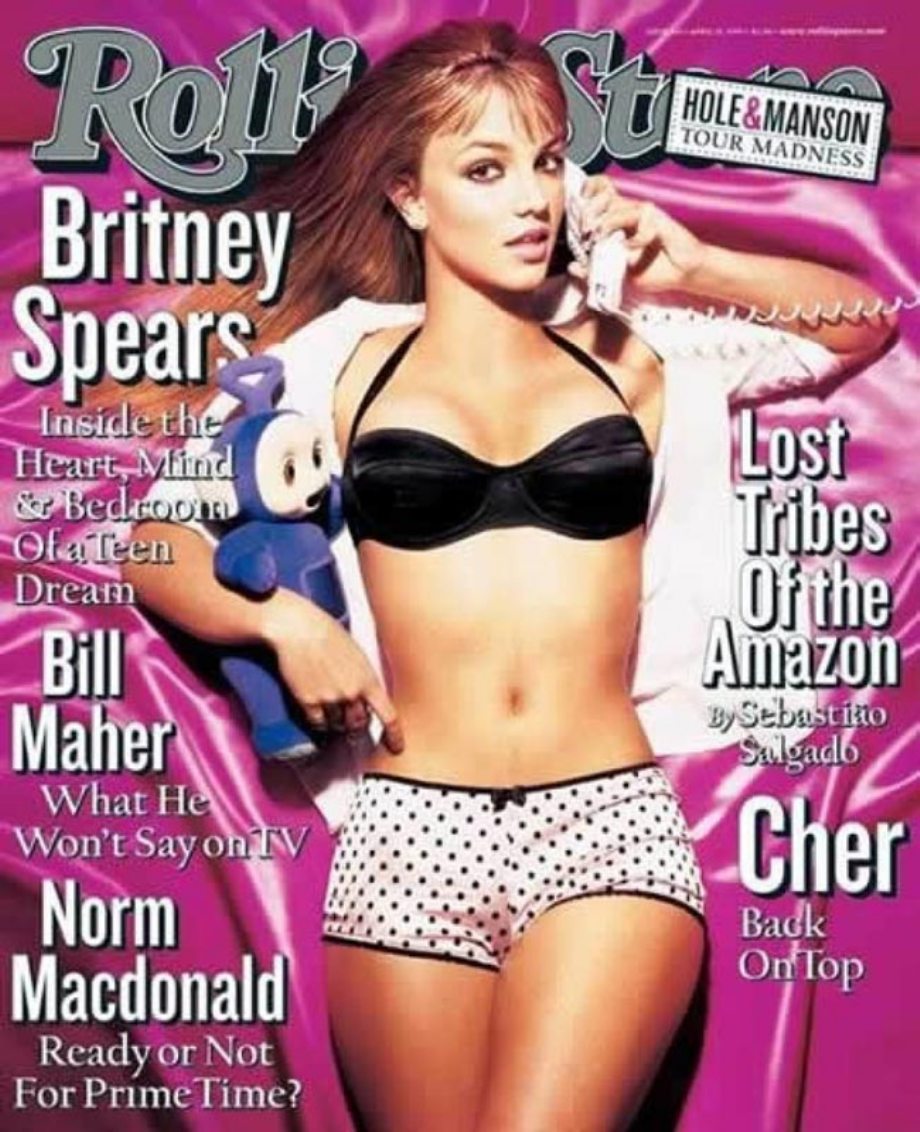

In April of that same year, Spears appeared on her first cover of Rolling Stone in a fashion that solidified her as a manufactured diva as opposed to "authentic" star: she lies on pink satin sheets in lingerie, holding a Teletubbie doll and talking on the phone. "Britney Spears," the headline reads, "Inside the Heart, Mind, & Bedroom of a Teen Dream." Spears is conveyed here as both girl and woman,2 forbidden and allowed, inaccessible and accessible. In short: inauthentic but desired, as divas typically are.3

Rolling Stone, April 1999

An Irishman, Glen Hansard also comes from "white trash" roots. At age thirteen, he quit school to busk (sing and play guitar for donations) on the streets of Dublin. At seventeen, Hansard borrowed money from his family to record a demo, which landed him a recording deal with Island Records; the signer-songwriter subsequently founded the group The Frames, "taking the name from his childhood fascination with bicycles," his Irish Music Central biography explains. For their first three albums, The Frames faced a rotating cast of members and record labels, distractions resulting in these records not receiving much circulation or critical acclaim. Irish Music Central explains that as the millennium approached, however, The Frames switched labels again, this time signing with a Chicago-based indie, Overcoat, before recording the band's fourth and finest effort, For the Birds. Where previous Frames records often suffered from overproduction, 2001's For the Birds (recorded in part by Steve Albini at his Electrical Audio Studios) boasted an intimacy and fragility that complemented Hansard's heartwrenching compositions.

If Hansard was gaining notoriety as an "authentic hipster star" at the center of The Frames, which he certainly was, the moniker was only strengthened by other projects he undertook during these years. As Billions, the artist collective of which Hansard is a part, explains, "Hansard garnered a reputation as not only an unparalleled front man, but also for his dedicated following and his grounded, real-life songs...In 2007, he and Czech songstress Markéta Irglová took home the Academy Award for Best Original Song for 'Falling Slowly' off the Once soundtrack," an indie-darling film in which Hansard also starred (in the early 1990s, he studied at the New York Film Academy School of Acting and was featured in the independent film The Commitments).

Hansard's reception as one who makes "heartwrenching compositions" into "grounded, real-life songs" places him among a certain echelon of artists — such as fellow musician Sufjan Stevens, filmmaker Wes Anderson, and writers Dave Eggers and David Foster Wallace — who all produce melancholic art that mourns something perceivably unnamable. Adam Kelly explains how Wallace specifically spearheaded a "new sincerity in American fiction" through publishing work which was "primarily about returning to literary narrative a concern with sincerity not seen since modernism shifted the ground so fundamentally almost a century before" (133). Reacting to the age of post-structuralist irony that dominated both the academy and artistic production during 1980s and '90s, artists like Wallace, Eggers, Stevens, and Anderson opened the door for a new (white, male) American sincerity (in the form of angst-ridden melancholy) to become mainstream and ubiquitous in the first decades of the twenty-first century. However, it is unclear that these new artists, such as Hansard, like their immediate predecessors, "really managed to escape narcissism, solipsism, irony and insincerity" (143). Such artistic production became especially potent following the events of September 11, 2001, and especially after the 2008 global economic crisis, when white masculinity was perceived as in crisis vis-à-vis Western neoliberalism's larger crisis. In reaction, all these aforementioned men produced art that harkens back to the post-War United States of the 1940s, '50s, and early '60s, the height of power for white men before the onslaught of social and Civil Rights movements.

Glenn Hansard (photo by Jeff Meade)

Mark Greif illuminates the public affect of these hipster celebrities, and their more everyday counterparts, quite well —

The hipster is that person, overlapping with the intentional dropout or the unintentionally declassed individual — the neo-bohemian, the vegan or bicyclist or skatepunk, the would-be blue-collar or postracial twentysomething, the starving artist or graduate student — who in fact aligns himself both with rebel subculture and with the dominant class, and thus opens up a poisonous conduit between the two. The hipster represents what can happen to middle class whites, particularly, and to all elites, generally, when they focus on the struggles for their own pleasures and luxuries — seeing these as daring and confrontational — rather than asking what makes their sort of people entitled to them, who else suffers for their pleasures, and where their 'rebellion' adjoins social struggles that should obligate anybody who hates authority. Or worse: the hipster is the subcultural type generated by neoliberalism, that infamous tendency of our time to privatize public goods and make an upward redistribution of wealth. (Greif xvi-xvii)

Though I do not necessarily agree with Greif's mostly pessimistic take on hipster (sub)culture, and in particular his painting of a "poisonous conduit" between classes, which I instead choose to generatively read as the (yet unrealized) potential of hipsters, his portrayal here is striking.4 Likewise, in Let's Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste, music critic Carl Wilson explains how "musical subcultures exist because our guts tell us certain kinds of music are for certain kinds of people." (Wilson 17) If the diva, typified by Spears, is seen as some idealized, hyperbolic version of the self that cannot exist, the hipster star, typified by Hansard, is some hyper-real version of the self for a (re)new(ed) consumer class at the beginning of the twenty-first century — feminized hipster men reasserting their masculinity through "redeeming" (disposable, inauthentic) diva pop to (authentic, sincere) hipster art.

In an examination of late '90s / early 2000s boy band and diva pop culture, Gayle Wald explains that in comparison to other modern popular music genres, "contemporary teenybopper pop has no such authenticating space written into its popular mythology, in part because it is not assumed to have the same organic genesis as these other genres... the point of origin of teenybopper pop is more often located within the music industry itself." Though there are certainly gendered and racialized differences between boy bands and female solo acts, the appraisal here is relevant to Spears as a manufactured entity, an ideal that constantly plagues pop divas, and perhaps in particular, their performance of ballads such as "Everytime." Though Spears (co)wrote the song, the affect of listening to a recording of "Everytime" is that it was manufactured for Spears to sing, and further, that the song was highly polished in post-production, further removing the record from Spears herself, devaluing her agency as a legitimate artist. In this way, Spears becomes not the artist behind the song, but the conduit through which the commercial production of the song can flow. She becomes merely a capitalist investment.

If Spears' embodiment of the staged offers her as a manufactured and specifically gendered pop diva, Hansard conversely embodies the everyday — the universally authentic — in a contemporary re-imagining of white masculinity under the sign of hipster cultural production. Simon Frith speaks to this line of reasoning, explaining that in popular culture performances, "the most interesting phenomenon is, precisely, the shifting boundary between the 'staged' and the everyday." (204) The ability for Hansard to shift the boundary between the staged and the everyday is best evidenced in the film that made him a hipster star, 2007's Once. In Once, Hansard plays a talented busker playing (heartbreaking) original compositions alongside traditional Celtic folk music on a busy Dublin street. One day — when a man steals his tips — Hansard meets a Czech woman (Markéta Irglová) who insists upon learning more about his music. Not surprisingly, the two fall quickly in love, though Hansard longs for his ex-girlfriend, the subject of many of his songs, and Irglová has a husband back in the Czech Republic. Their instantaneous love unfulfilled, the two record a forlorn demo together, which Hansard plans to take to London in an effort to both win back his ex and attain a record deal. Hansard in Once typifies Frirth's staged-everyday binary in that he performs in the most staged of dramatic genres, the musical, while also deploying earnest, white masculine bootstrapism: a (literally and figuratively) broke musician, Hansard pulls himself up, records a breathtaking demo, and rides off into the sunset to win back his girl and take over the musical world. Likewise, by re-recording a "more authentic" version of "Everytime," Hansard redeems the song through his own masculine handicraft.

Beyond authorial biography, which is also to say, a clear gender(ed) difference, what is most starkly divergent between the Spears' and Hansard' versions of "Everytime" is each recording's instrumentation. Spears' composition begins with a synthetic piano melody accompanied by a chiming music box; given a priori knowledge most listeners, casual and fan alike, bring to any Spears performance, we assume she is playing neither of these. That Spears has not been seen in any culturally memorable performance playing an instrument only adds to her persona as a manufactured pop diva (as opposed to, for example, Lady Gaga, perceived as a diva more authentically connected to her music vis-à-vis frequent appearances behind a piano onstage). Throughout Spears' composition, the instrumentation produces an affect of faux musicality: electronic strings soon pipe in, resulting in a melody ready-made for Muzak stations in dentist office waiting rooms around the world. The song fades out, literally, to the lilting music box accompanied by a heaving female sigh, perceived to be Spears herself.

Hansard's cover of "Everytime," on the other hand, begins with a simple guitar strum joined immediately by a staccato, plucking violin (Hansard is paired in this recording with The Frames' violinist Colm Maclomaire). Although Hansard is clearly not as iconic as Spears playing Britney the diva, he is an icon of a different rite; through creating an authentic white trash hipster aesthetic, literally using his own two hands to craft a beautiful cover, Hansard not only redeems "Everytime" from trash to Art, but also becomes the iconic (white, male) everyman. In the most prominent visuals we have of Hansard, in fact, he is pictured with his guitar, most often (such as in promo materials for Once) or at a piano; a simple YouTube search for his live performances finds him playing his own instruments almost constantly: from the aforementioned guitar and piano to forays into the drums and harmonica. The hipster aesthetic is certainly a strange conglomerate of mismatched contingencies; it at once values (costly) handcraftsmanship and a sense of apathy, of not caring. Combined, these contingencies are coded as that all-too-relevant hipster buzzword: authentic. To look at the person of the hipster—here Hansard—is to observe individuals-cum-collectives wrapped up in a constant quest for authenticity, or the everyman's everyday. Hansard's cover of "Everytime," through its essential hipster instrumentation, butts up against Spears' manufactured composition in interesting ways. Most telling, hers comes with an orchestrated inauthenticity that leaves the song affected as trite, bubblegum, teen-girl music; Hansard's, however, garnishes an authentic affect of emotion, putting him in line with certain (again, white, male) singer-songwriters from Johnny Cash to Josh Ritter. This is ironic given Hansard is, in fact, covering Spears' song, but not surprising given its placement on volume two of Even Better Than the Real Thing (which, it is worth noting, also includes redeeming covers of songs by pop divas Beyoncé and Natasha Bedingfield).

Through both his (re-)authorship and instrumentation, Glen Hansard has seemingly redeemed Britney Spears' "Everytime," taking the bubblegum ballad from trite girly pop to authentic musical production. To be clear, I must be honest in my analysis: though I love Spears — my second chapbook, Brit Lit, is solely poems about her — I prefer Hansard's arrangement. It is important, however, to ask why and how Hansard is allowed to redeem Spears' music in the first place. Put simply, he is allowed to do so because girly pop music is automatically, through specters of gender, celebrity, and the marketplace, seen as trite and in need of redemption. Through his cover of "Everytime," Hansard accomplishes this redemption by drawing on both his own "universally authentic" hipster biography and his very musical know-how to arrange a more acceptable song. This critical reception, of course, comes at a cost to Spears as both a performer and a woman. To queer one of her later lyrics, we might begin to ask, "don't we know this type of masculinity is toxic?"

D. Gilson (dgilson.com) is the author of I Will Say This Exactly One Time: Essays (Sibling Rivalry, 2015); and Crush with Will Stockton (Punctum Books, 2014). This fall he will become an Assistant Professor of English at Texas Tech University, and his work has appeared in Threepenny Review, PANK, The Indiana Review, The Rumpus, and as a notable essay in Best American Essays.

WORKS CITED

"Britney Spears Biography." Rolling Stone. Web. 29 Nov 2013.

Browne, David. "In the Zone." Entertainment Weekly 21 Nov 2003. Web. 2 Dec 2013.

"The Frames: Biography." Irish Music Central. Web 30 Nov 2013.

Frith, Simon. Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1996. Print.

"Glen Hansard." Billions. Web. 30 Nov 2013.

Greif, Mark. "Introduction." What Was the Hipster: A Sociological Investigation. Ed. Mark Greif. New York: n+1 Foundation, 2010. Print.

Kelly, Adam. "David Foster Wallace and the New Sincerity in American Fiction." Consider David Foster Wallace: Essays. Ed. David Hering. Los Angeles: Sideshow Media Group, 2010. Print.

Wald, Gayle. "I Want It That Way: Teenybooper Music and the Girling of Boy Bands." Genders 35 (2002). Web. 1 Dec 2013.

Wilson, Carl. Let's Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste. New York: Continuum, 2007. Print.

- "Britney Spears Biography." Rolling Stone. Web. 29 Nov 2013.[⤒]

- That one of her biggest hits following this period would prove to be a song lamenting, "I'm not a girl, not yet a woman," should be of little surprise to the cultural critic.[⤒]

- See Richard Dyer's Stars. (2nd ed., British Film Institute: London, 1998. Print.[⤒]

- Greif organized a symposium and the magazine n+1 subsequently published its proceedings under the title What Was the Hipster: A Sociological Investigation (n+1, 2009). As the title suggests, participants understood the hipster as a quickly dying phenomenon. But seven years post, this does not seem to be the case, even as the figure has morphed; the hipster's continued cultural cache can be seen, in fact, by the continued success of publications such as n+1, retailers such as Urban Outfitters, and lifetstyle movements such as "farm-to-table" eating.[⤒]