Leaks: A Genre

The Leak as Genre: An Introduction

Jonathan Franzen's 2015 Purity is a novel ostensibly about leaks and the paranoia they capture and enable.1 In the novel's world, which represents and embellishes our own, large systemic conspiracy is assumed as a condition rather than revealed as an event; the existence of "some corporate master plan" is so taken for granted that it becomes the source, rather than the target, of a metaphor (42). It's not that the novel narrates any specific plan by any specific corporation to take over the world; rather, the novel registers a world in which that's literally commonsense, in which it's naïve to think otherwise. This is a world, too, in which leaks are as common as corporate master plans — leaks that are most often orchestrated by Andreas Wolf, who runs Project Sunshine, a competitor to WikiLeaks (Wolf claims his project is more "purpose-driven" than the "neutral and unfiltered platform" of his rival [58]). But the content of these leaks is not the subject of the novel, nor do they ever seem to change the world the novel oversees. There is mention of a "document dump" that "casts a devastatingly unflattering light on the federal government's settlement with the banks," but this produces nothing except a late-night conversation among housemates; there is mention of an "upload [of] Australian government e-mails" that proves deception and willful negligence regarding endangered species, but this does not even produce conversation as all (47, 257). This novel that is about leaks and the narratives that unfold in parallel to them never tells the story of how a leak itself came to be or what it contains. In the narrative logic of Purity, a leak cannot propel plot; it is background information, like governmental conspiracy, rather than event.

Purity symptomizes in its form — the failure of leaks to be functional for plot — an emerging convention for how to read leaks and what they mean in a world in which they have become increasingly common and even routine. Consider the frequency with which WikiLeaks surpasses its records for publishing classified material. In 2010 alone, it released the "Collateral Murder" video in April, the more than 75,000 documents of the "Afghan War Diary" in July, the nearly 400,000 documents of the "Iraq War Logs" in October, and, in November, the quarter million diplomatic cables that would precipitate "Cablegate." It could have been the year of political leaks, but it turned out to be only a year of leaks, surpassed in subsequent years by such document dumps as the 2017 "Vault 7" detailing CIA software capabilities, including United States hacking tools. Many of these leaks have cast American diplomacy in, to use Purity's language, a "devastatingly unflattering" light. But just as leaks are incidental to the plot in Franzen's novel, none of these recurring embarrassments effected a dramatic re-organization of foreign relations. Indeed, to the extent they had an effect, it was to confirm suspicion rather than provide revelation. Within a day of the 2010 Afghan War Diary, a letter to the editor of the New York Times asserted that "the most shocking aspect of the secret archive is how unshocking it is"; the picture painted by the Diary "is exactly the picture that has been drawn by journalists, political observers and other witnesses, to say nothing of scores of returning soldiers and officers."2 It is not that any member of the general public had managed to read all of the 91,000 documents collected in the Diary in twenty-four hours. You did not have to, the writer seemed to say, because there is something in the nature of a leak that its revelations will be of things you already knew, or — and this is a point to which I will return — at least you felt you knew.

When the Times introduced the previously largest leak of government documents, the Pentagon Papers on June 13, 1971, it took a couple of days for the paper to even know to call its archive a "leak," and many more days for people to decide what they felt about it.3 The existence of shared expectations and conventions for identifying and reading the disclosures of WikiLeaks suggests that the "leak" has achieved the status of a genre today — what Sianne Ngai might call a "minor" genre.4 The past generation has seen an exceptional increase in the number of leaks for a number of bureaucratic, structural reasons — not least of which is the simple fact that the government tends to overclassify as much as 90% of material and so there is simply more available for leaking.5In his study of the relations between the American government and the press, Sam Lebovic notes that leaks became "institutionalized" as early as the 1950s, immediately after the formation of national intelligence organizations, and that already by the 1980s, government studies were reporting that nearly half of federal policy-makers had leaked secrets to journalists.6 Despite paranoia over clamp downs on the freedom of the press, the contemporary legal landscape is by and large permissive of leaking behavior, especially of distributors who publish leaked information — a permissiveness afforded in part by the jurisprudence regarding leaks beginning with the Pentagon Papers, which the Supreme Court affirmed the Times had a right to publish.7 At the level of action rather than discourse, there is what David Pozen calls a "persistence ... of permissive neglect" around governmental leaking.8

This article, however, is not about the structural and historical conditions that enable the proliferation of leaks.9 I am interested instead in the development of conventions and norms around what a leak is and how to read it — and the conditions that have made it possible for a public to know what a leak is about and how they ought to feel about it before even reading a word of the documents it covers. The consolidation of the leak as a genre is another lesson of Purity, which assembles a diverse cast of characters who nonetheless seem to share a sense of what leaks are and what they do not do. The novel indexes how much public consensus there is around the conventions of reading leaks, despite the public's political polarization. Tzvetan Todorov, who has argued that some speech acts become genres while others do not because "a society chooses and codifies the acts that most closely correspond to its ideology," might say this consensus means that leaks put us in the presence of hegemony.10 But I will show it is not so much ideology as fantasy that leaks mediate between a public and its state: not so much ideas as affect. Thus, leaks in Purity cast a "devastatingly unflattering light" on national governments at the same time that they fail to provide grounds for political transformation. I will return to Purity in the final section of this essay; for now, I want to tease out this lesson that the novel seems to offer: the effects of leaks, it seems to say, are primarily affective rather than material or even epistemological. Leaks create embarrassment more than information.

In July 2017, the United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs released a report on an "Avalanche of Leaks" during the first four months of the Trump administration. Its first conclusion on these leaks of "sensitive information," which were "potentially damaging," was that they "presented President Trump in a negative and often harsh light, with some seemingly designed to embarrass the administration." Harm to national security was "potential"; embarrassment to the administration was immediate. In this discursive landscape, the "sensitivity" of information starts to play double duty, seeming to refer less to a vulnerable nation and more to an easily offended personality.11

As for Trump himself, who has publicly condemned leaks and called for a speeding up of the leak prosecutions that were already accelerated under President Obama (whose administration more than doubled all prosecutions from all previous administrations combined), it would turn out that one frequently embarrassed by leaks was a leaker himself.12 On Twitter, the President has re-tweeted Fox News stories that contain classified information; in person, he has been reported to tell Russian officials classified information. This last offense lead to a front page headline on May 16, 2017, in the New York Daily News: "Leaker of the Free World: Trump Spilled ISIS Secrets to Russia." Feminist scholars have showed how leakiness has tended to be sexed and gendered, in order to shame the woman who menstruates and therefore cannot keep in her fluids or is too emotional and cannot keep in her tears: "[w]hen we cry, orgasm, are sick, or get nervous, we feel we have lost control of ourselves and are embarrassed as our liquids leak out into the world."13 Laura Kipnis has more recently extended leaking to a linguistic phenomenon of subjects leaking secrets: "Human beings can't help spilling clues all over the place about the mess of embarrassing conflicts and metaphysical anguishes lodged within."14 In every case, leaking produces femininity, and femininity apparently produces embarrassment. In a counter-tradition begun by Margrit Shildrick, some have turned to the association of leakiness with femininity to promote a more general fluidity that opens up allegedly closed systems by transgressing borders.15 In this reappraisal of the role and value of leakiness, what was considered a feminine liability — the supposedly uncontained corporeality of women, which bars their access to neoliberal professional spaces that value an individual autonomy coded as masculine — becomes instead a site of collective contestation, the ground of a "fluid liberatory mode."16 But the shaming language of "Leaker of the Free World" suggests the persistence of norms for gendering leaking, now applied to the phenomenon of leaking secrets. Casting Trump as a leaker is one strategy for feminizing and embarrassing him.

The May 16, 2017, cover of the New York Daily News parodied President Trump for sharing highly classified information with Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak in a closed meeting at the White House.

It is in this more specific sense that I discuss the leak as a genre, defined by Lauren Berlant as an "aesthetic structure of affective expectation," a "formalization of aesthetic or emotional conventionalities."17 Leaks come with expectations that someone is going to be embarrassed; that is part of their function as a genre. In turn, they also push slightly beyond Berlant's theory of the "waning of genre," an important and powerful corrective to Jameson's diagnosis of postmodern culture as a waning of affect. Berlant's point is that today's world sees not so much a dampening of the circulation of feelings but a disruption of how those feelings are supposed to be organized and mediated and of expectations regarding where to find them.18 You turn on a comedy, but somehow you land up in the genre of horror; you're breathless and then you're crying when you thought you signed up to laugh. Berlant's description of the contemporary, however, goes beyond genre in this sense of categories of cultural production. Genres are not only types of literature, movies, and music; they apply to other social categories as well, if by genre we mean a convention in which members of a public recognize themselves as having shared definitions of x: a comedy is supposed to be funny, yes, but also: a man is supposed to by y or America is supposed to be z. The waning of genre is then the waning of commonsense: an erosion of a sense of having something in common with others, whether a common object or experience or affect.

There are different ways of telling the story of a present losing a sense of commons or decoupling from structure, just as there are many different regimes or institutions whose disorganizing can be told. The story I lean on here is the historical shift from Foucault's disciplinary society — a society cut up into discrete institutions cut up into discrete roles — to Deleuze's society of control, in which sets of behavior are modulated rather than sequenced.19 In such a society, institutions — paradigmatically those of the bureaucratic state — fail to contain and maintain themselves and their infrastructures, in turn failing to discipline their members into appropriate behaviors and roles. The 1956 "Report to the Secretary of Defense by the Committee on Classified Information" explicitly identified leaking as a problem of failed discipline: "We have been told that information security is a state of mind and not a set of rules. With this we agree. We further think that a state of mind is part of morale, and as such is a facet of discipline, and discipline is a command function."20 As Lebovic argues, the midcentury security state increasingly turned to "regulating the employee rather than the journalist" in order to control leaks; the authors of this report similarly thought that leaks could be stopped if only employees of government agencies, understood essentially as soldiers, could be disciplined.21 They doubled down on a program of disciplinary society, strengthening institutions in order to administer proper behavior. But such a strategy seems increasingly untenable as institutions become larger, more distressed, more virtual, and more permeable. The explosion of leaks in the sixty years since 1956 symptomizes a condition of disciplinary decay, a government whose institutions cannot program the expected behaviors and in turn cannot contain its information.

Given the regularity with which governance presents spectacles of its weakness, the age of the leak might also have been the age of the de-tethering of citizen from state, a disruption of the contract by which subjects invest and submit to the security of the nation as a safeguard of their own autonomy. In this essay, however, I tell a different story about the attenuation of attachment between subject and state. I will argue that leaks provide a repeated ritual for re-attaching to the state, not in spite of but because of its fantastic diminishing of power to contain itself. To put it frankly: there are pleasures afforded by someone else being embarrassed, and the leak as a genre attaches people to the state because of the pleasure provided by it. To be sure, this is a re-shuffling of the terms of attachment, and one of the stories I tell in the following sections is how leaks participate in a movement from identification with the state to interaction with the state, in which the state is not an image of identical similarity but of affective difference and fantastic disrepair.

If the leak takes the decline of disciplinary society as a condition rather than problem, then the leak is not a symptom of genre's waning, but of a genre that emerges in order to process the waning of institutions.22 I begin in the following section by returning to an earlier period and the discursive precedent for the leaks of the past decade: the Pentagon Papers. Within three weeks at the end of June 1971, this leak produced more than a half dozen federal court opinions, one from the Supreme Court; hundreds of editorials; and many more memos and letters to newspaper editors, all of which assembled a common language for talking about leaks. By moving through this highly compressed and rapid development of discourse, I establish the contours of the genre we have inherited today. This is not to claim that the Pentagon Papers and more recent leaks are identical or even historically accurate analogs. While Daniel Ellsberg, the original source of the Pentagon Papers, has called for seeing a similarity between them and Wikileaks — both have the ambition and, according to Ellsberg, the means of interrupting "wars on false premises" — most scholars have begun to enumerate the many differences between the two projects. WikiLeaks dumps are incomplete archives — randomly selected documents rather than complete bounded volumes — and therefore lacking in both context and content.23 Relatedly, the sources of what Margaret Kwoka calls the "deluge leaks" of today's world lack the intimacy with and knowledge that former "whistleblower" leakers like Ellsberg had with the materials they were leaking.24 While the Times was a publisher of leaked information, WikiLeaks is more analogous to a source of leaked information, and sources lack the jurisprudential discretion the Supreme Court granted to the Times in 1971.25 The Times is an American company subject to American laws, whereas WikiLeaks is not (there could be no landmark Supreme Court case in which WikiLeaks was a party); and the Times is an organization of professional journalists subject to traditions and codes of appropriate deliberations over the management of information, whereas WikiLeaks is not.26 Perhaps most importantly, the informational situations in which the Pentagon Papers and WikiLeaks act are worlds apart; with his Papers, Ellsberg had a specific goal, and leaking was a means to an end, whereas WikiLeaks sometimes seems to "revel ... in the revelation of 'secrets' simply because they are secret."27 Ellsberg leaked because he had to, while WikiLeaks leaks because they can in a world of wider information accessibility and easier transmission.

I do not intervene in these debates because my interest is in the development of a discourse around objects, leaving to one side a comparison of objects themselves. Here, I draw some inspiration from Adena Rosmarin, who has argued a genre is "a kind of schema, a way of discussing a literary text in terms that link it with other texts and, finally, phrase it in terms of those texts ... We are able, then, to read texts that are different as if they were similar because we are able and willing to make the edifying mistake of classification."28 We read WikiLeaks as if they were like the Pentagon Papers; to show they are not equal is still to operate within the universe in which they are at least "linked." In particular, I track in the following section the language developed to discuss the Pentagon Papers in order to see the affective affordances developed by leaks as a genre. I then return, in the concluding section of the article, to the present and how the genre lives in a world of other unstable genres including a realist novel like Purity, which helps to further contextualize the leak and pick out some of its thematic dimensions.

The Pentagon Papers, or, How "Leak" Lost Its Scare Quotes

Before they became the "Pentagon Papers," the 47 volumes of United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945-1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense were called the "Vietnam Archive." That was the headline when the New York Times began serially publishing excerpts from and summaries of the study in its Sunday, June 13, 1971, issue, and it returned in the headlines on June 14 and June 15 before the District Court of New York granted the United States a temporary injunction enjoining the Times from further publication. In the articles introducing the study, the Times drew most of its attention to the study's archival nature: its "7,000 pages — 1.5 million words of historical narrative plus a million words of documents — enough to fill a small crate."29 Perhaps the most frequent verbs used in the articles were "reveals" and its synonyms (e.g., the study "discloses a vast amount of new information"), and this language of uncovering, combined with the Times's protection of its source's identity, indicated the secret nature of the report. But the story was ultimately the information itself rather than how it had been uncovered: "The overall effect of the study ... is to provide a vast storehouse of new information — the most complete and informational central archive available thus far on the Vietnam era."30 The contents of the leak, rather than the leak itself, were what made this a front-page story.

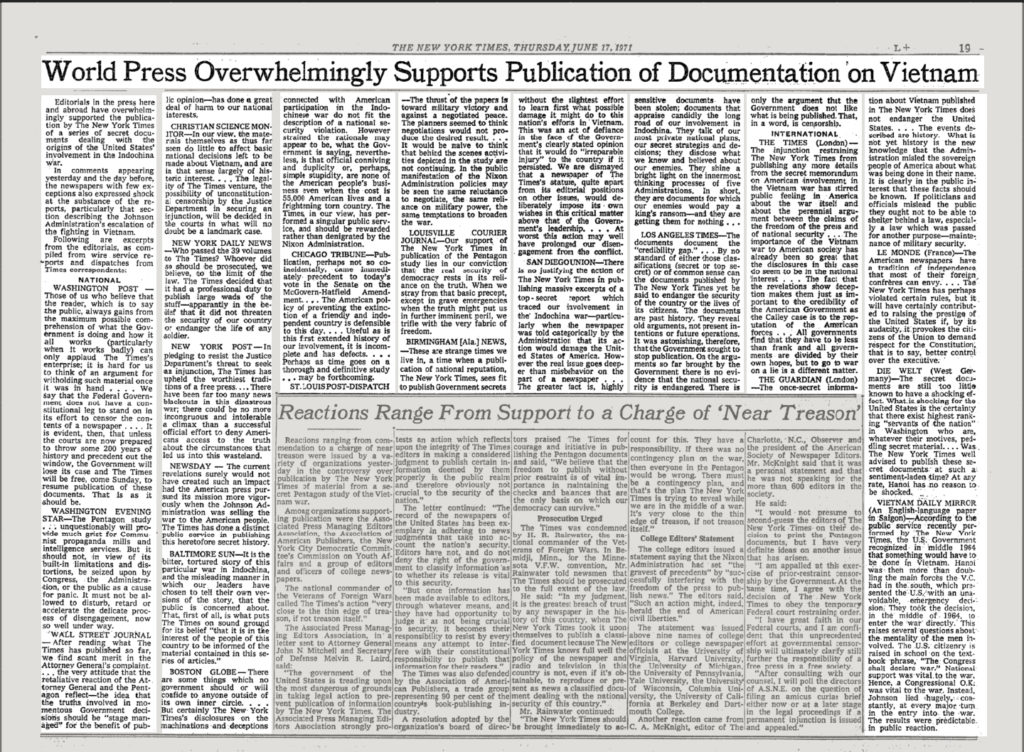

Indeed, "leak" did not enter into the discourse until several days later, after and in response to the government's attempted actions to halt more disclosure. On Tuesday, June 15, the United States government filed for a restraining order against further publication from Judge Murray Gurfein, who had been appointed to the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York by Richard Nixon and sworn into office only the day before. The text of the government's complaint, which the Times published in its June 16 issue, claimed that without injunction, "the national defense interests of the United States and the nation's security will suffer immediate and irreparable harm."31 The formula of "national security" versus free speech quickly came to characterize the debate over the Papers, and because Gurfein granted a temporary restraining order until the case could be heard — and because this order was successively renewed throughout the course of appeals through the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and then the Supreme Court, publication was effectively enjoined until the last Court's decision on June 30; it was this debate over the archive's release, rather than the archive itself, on which the Times necessarily focused its front page coverage for the following two weeks. On June 17, the Times devoted almost an entire page to a roundup of excerpts from other newspapers' editorials on the matter under the headline "World Press Overwhelmingly Supports Publication of Documentation of Vietnam." Those who praised the Times did so by reference to its courage of speech, often with an unsubtle dose of American exceptionalism (it was claimed such a freedom of press would not be possible in, for instance, France or Australia). The few who decried the Times did so by reference to "defense interests ... and the nation's security," often by way of the compromised syllogism that the nation's wartime enemies would want the documents; therefore those who wanted the documents were the nation's enemies.

On June 17, 1971, the New York Times published a selection of newspaper editorials that largely supported and even lauded its previous reporting on the Pentagon Papers.

But as discussion intensified both within the pages of the Times and within the courts in which the Times was a party, the government's phrases came under stress. The discourse in turn shifted, and as the Times continued to devote large portions of its paper to the affidavits, oral arguments, and decisions involved in the subsequent court cases, it allowed readers to absorb these shifts and engage with emerging idioms. First, it reminded readers that the archive in question was indeed a historical archive, pertaining to (albeit very recent) historical events, rather than to, say, the present movements of troops or even ongoing international negotiations behind closed doors. Thus both "security" and "immediate ... harm" seemed suspect, as the Times said in oral arguments before Judge Gurfein: "The security interest is not visible with the naked eye." The argument for national security seemed especially weak because, while the Times was temporarily enjoined, the Washington Post had begun to publish from a copy it had separately received.32 "Another installment of [the] story has been published," the Times pointed out, and yet "[t]he republic stands." In examination, Gurfein began to worry about "the guise of security" as an excuse for the suppression of speech. The government in turn edited its phrases on the fly: "The national defense interests of the United States and the nation's security" became, simply, "national interests"; "immediate and irreparable harm" was reduced to "irreparable harm" only.33

The phrases "national interests" and "irreparable harm" were taken up widely in subsequent public discussions of the case. The former proved popular because of its versatility, used by those who were anti- and pro-publication alike: it simultaneously relieved those against publication from having to claim a military concern "visible with the naked eye" and positioned those for publication to claim their own prerogative for deliberation. By June 24, Paul C. Warnke, the original leader of the study, was already being quoted in the Times admitting there was "no security threat" in the materials published so far, although "certain elements" of the unpublished portions of the study "could adversely affect the national interest if prematurely revealed."34 What precisely this "interest" was remained undisclosed, but the point is that "interest," unlike "security," reveled precisely in this vagueness. Because "interest" was undefined, however, it was also open to larger public contestation. Whereas some might be willing to defer to, say, the National Security Council (founded in 1947) as to the definition of "security," there was no "National Interest Council" to supervise interest's contours. In his decision not to enjoin the Post from publication of the papers on June 21, Judge Gerhard Gesell of the District Court of the District of Columbia noted the identity of national and public interest: "It should be obvious that the interests of the Government are inseparable from the public interest. These are one in the same and the public interest makes an insistent plea for publication."

In the editorial pages of the Times, people began to debate "violently conflicting views of what best serves the national interest."35 In the world imagined by the idiom of security, "violence" was a material reality between warring states; but "interest" suggested instead a competition internal to a state, one between warring regimes of values. The us-versus-them logic of global space was absorbed into a dialogic battle within the "us," an absorption that has only accelerated since the end of the Cold War and the decline of its bipolar organization of military power.36 As the single state absorbs agonistic conflict and lacks the ability to geospatially differentiate its antagonists — and as security correlatively transitions into interest — the state's register shifts from physical containment to interior will. Indeed, the overall effect of dwelling within the discursive space of "interest" was an imagination of the state as a psychological more than physiological being: if security seemed to refer to a physical body whose borders needed to be protected from physical assault, interest seemed to summon a desiring subject whose wants needed to be satisfied.

Such a move from a physical to a psychological understanding of national health had been made explicit in foreign policy discussions and declarations within the United States government in the early years of the Cold War. In the so-called "Long Telegram" of 1946, written in response to a State Department query for explanation of recent antagonistic behavior by the Soviet Union, George F. Kennan, then deputy chief of the United States diplomatic mission in Moscow, argued that the Kremlin did not act out of "any objective analysis of the situation beyond Russia's borders" but, instead, out of a "traditional and instinctive Russian sense of insecurity."37 The "insecurity" was in part geographic, drawing upon the nation's expansive and vulnerable territory, but it was also mental, accumulated through multiple generations of Russian leaders' anxiety about their legitimacy to rule. To secure this legitimacy, Kennan argued, the leadership turned to a fantasy of being surrounded by a totally corrupt and hostile world; the Russian people needed to invest in a centralized government in order to defend against a pervasive threat. As Kennan later elaborated in his discussion of the leadership's "great ... sense of insecurity" in a vastly influential 1947 Foreign Affairs article that introduced the Cold War "containment" strategy of international relations to the American public, the "pattern of Soviet power" had become "the pursuit of unlimited authority domestically, accompanied by the cultivation of the semi-myth of implacable foreign hostility."38

Kennan's point, which procured for him instant prestige in the diplomatic community and a promotion to policy writing that would return him to Washington, was that Russian aggression could not be countered through a rational calculus of military chess, but required psychological maneuvering as well. They key was to puncture the "myth" of a hostile world and create a counter-fantasy of American moral, in addition to military, might. At home, this fantasy required the cultivation of the free world's "courage and self-confidence": "This is [the] point at which domestic and foreign policies meet. Every courageous and incisive measure to solve internal problems of our own society, to improve self confidence, discipline, morale and community spirit of our own people, is a diplomatic victory over Moscow worth a thousand diplomatic notices and joint communiqués."39 The strategy was in part codified in the 1950 National Security Council Report 68 (NSC-68), although written after Kennan's departure from the State Department. As the Report recommended, "We must make ourselves strong, both in the way in which we affirm our values in the conduct of our national life, and in the development of our military and economic strength"; America, unlike Russia, had a "unique degree of unity," and, to counter Russian ideology, "expressions of national consensus" should be promoted.40 Just as the Russians, according to Kennan, had imagined national security as a kind of psychological security, retarding the anxieties of legitimacy, the National Security Council imagined national "strength" to be as much about national belief — "confidence and courage" — as physical might.

In his history of American Cold War strategy, John Lewis Gaddis remarks on this "startling" coding of national security as depending "as much on perceptions of the balance of power as on what that balance actually was": "Judgments based on such traditional criteria as geography, economic capacity, or military potential now had to be balanced against considerations of image, prestige, and credibility. The effect was vastly to increase the number and variety of interests deemed relevant to national security, and to blur distinctions between them."41 One consequence of viewing the "Soviet challenge as largely psychological in nature" — caused by the psychological insecurity of Russian leadership and to be corrected by the psychological confidence of the United States and its allies — was that national "interest" depended in part on securing the trust of its citizenry so as to present to the world a strong front of confident consensus.42

As the court opinions, public discussions, and editorials surrounding the Pentagon Papers suggest, however, this alignment of "interest" with "security" by way of consensus was difficult to sustain within the citizenry at large. The public debates over what constituted interest introduced not an affective convergence, but the possibility of affective dissonance and debate. Eric Santner has argued that, as we moved from societies of the spectacle to societies of discipline and as the symbolism of sovereignty migrated from the locatable and specific body of the sovereign ruler to the more diffuse body of the democratic people, a biopolitical pressure developed around the health of the people on which an image of sovereignty is conceived and sustained.43 In such a society, leakiness might be seen as a threat manifest in the bodies of the body politic, and especially in the feminine and feminized members of it. But the shift from security to interest, and therefore from a more physiological to a more psychological schema of the nation's personhood, suggests a further turn in Santner's story of sovereignty: from the regulation of bodies to the regulation of interiors. As demonstrated in the debates around what "interest" constitutes, this transition from a physiological to a psychological sovereign also disrupts an easy calculus of identification between nation and citizen, and in turn disrupts the pressures put on the latter by the former. Both states and people have contradictory or competing interests; the drama of sovereignty has in turn become a narrative about how these contradictions are unfolded and managed.

The transition from security to interest in the para-Pentagon Papers discourse went hand in hand with the reduction of "immediate and irreparable" to simply "irreparable," which further elaborated the personhood of the affective state. Both sides of the debate came to agree that roads, ships, and military bases can be repaired even when bombed; but what is truly irreparable is a bad reputation. Editorials and letters to the editor in the Times consistently argued that "the only irreparable damage is to the reputations of this and past administrations"; "the Government suit boils down to the gut issue of the embarrassment of certain inept national leaders, which embarrassment is termed 'defamation' or 'irreparable injury' in one or another system of political rhetoric."44 For those against publication, however, even an individual's or administration's reputation was worth defending if it was necessary for a good diplomatic position in the world. Henry Kissinger, in his 1979 memoir The White House Years, recalls that his aversion to the leaking of the Vietnam study was that it would deflate diplomatic negotiations then developing, for instance with China:

Our nightmare at that moment was that Peking might conclude our government was too unsteady, too harassed, and too insecure to be a useful partner. The massive hemorrhage of state secrets was bound to raise doubts about our reliability in the minds of other governments, friend and foe, and indeed about the stability of our political system.45

Note once again how the language of security, routed through diplomatic interest, has picked up anxieties more affective than material, anxieties that deal with the ways in which the nation is perceived in the world (with "instability" similarly echoing a language of the mentally unstable).

This worry about the nation's perception on the global stage explains why the most frequent keyword in both public and official discourse over the Pentagon Papers in June 1971, besides national interest and irreparable harm, was "embarrassment," again used by both sides of the debate: the publication of the papers "will temporarily embarrass the United States government in the eyes of the world and to its own citizens"; classification is an "official convenience, the opposite of official embarrassment"; "isn't it ... true that the secret processes of government — if they are sensitive enough to be classified — can be released only at the risk of embarrassing the nation and harming its foreign relations?"; "[b]y what right do newspapers presume to print official information which may embarrass the Government and give comfort to the enemy?"46 It is interesting to note that embarrassment often comes in the form of a rhetorical question when deployed by those against publication — making the danger seem more floating than localized — but the general point is consistent across contexts: a nation with interests also has an interest in not being embarrassed. What remained to be decided was whether embarrassment was constitutionally prohibited. The Supreme Court ultimately concluded, "The dominant purpose of the First Amendment was to prohibit the widespread practice of governmental suppression of embarrassing information."47

Fascinatingly, the correlation posited by the case — where disclosing information (which for some was disclosing the "truth") was likely to be embarrassing — quickly afforded a situation in which facts themselves began to be identified according to what they produce affectively. Some of the Times editorials and letters to the editors — again on both sides — even came close to making a slip from saying the truth can be embarrassing to saying truth by definition is embarrassing, or that something only feels like the truth if embarrassment is in the air. James Hagerty, then vice president of ABC and formerly press secretary to Dwight D. Eisenhower, argued, "Truth can be embarrassing and it is the duty of the news media to seek it out and report it"; a letter to the editor a week later complained that the Times had adopted an editorial process of publishing only those specific excerpts of the forty-seven volumes that it "figured would embarrass."48 Whereas earlier in the debate, people were simply trying to decide who was being embarrassed — whether that individual, this administration, or the nation as a whole — by the conclusion of the month, embarrassment has almost lost its subject (or object) altogether. In the formula "truth can be embarrassing," a feeling of embarrassment starts to float around truth, rather than in the persons themselves implicated by the truth.49 We have inherited a similar formula today. This is how Žižek talks about the non-surprise of the documents disclosed by WikiLeaks: today, "we face the shameless cynicism of a global order whose agents only imagine that they believe in their ideas of democracy, human rights and so on. Through actions like the WikiLeaks disclosures, the shame — our shame for tolerating such power over us — is made more shameful by being publicized."50 Note the suggestion that shame was supposed to lodge in the global order but gets moved around and lodged in "us." A leak makes no claim on who is shamed, but it is part of the nature of the leak that shame is at least nearby.

In lining up a discourse with affect, leaks have come to act like a genre, understood by Berlant as an affective contract. But by making shame float above a situation instead of grounding it in a person designated in advance, the leak also complicates many theories we have of genres. Fredric Jameson, for instance, has named genres "social contracts between a writer and a specific public"; Ralph Cohen, who disagreed with Jameson, nonetheless maintained a similar role for "a writer" negotiating with a public: genres are "historical assumptions constructed by authors, audiences, and critics in order to serve communicative and aesthetic purposes."51 But it is hard to place the role of an author when it comes to leaks: the literal writers of the documents Ellsberg published probably thought they were "participating" in the genre of, say, the memo or the report while they were writing.52 The leak is a genre weirdly not authorized, or else its "author" is more like its publisher: in the case of the Pentagon Papers, Ellsberg; in the case, more recently, of WikiLeaks, perhaps Julian Assange. This is not to deny that the writers of memos may be aware of the future life of their documents as leaks or even may, through leaking, intend interpersonal communication rather than critical disclosure. David Pozen has demonstrated that in a bureaucratic world of zealous over-classification, leaking is even a standard means by which the government communicates with itself (between departments) and with the public (when it wants to say something technically classified but hardly secret).53 What this situation crucially demonstrates is a crisscrossing of intentions so that leaks have become overburdened with possible meanings and overdetermined with possible motivations by multiple possible authors. Sometimes writers and leakers are communicating within governmental bureaucracies. Sometimes they are communicating with a citizenry. Sometimes they may even be acting on behalf of a foreign government. Usually, the event of a leak is a convergence of multiple kinds of interests. It is often difficult to refer a leak to a single author; it is almost always impossible to refer a leak to a single institutional affiliation in which that author plays a role. But this slipperiness of the author — or, more generally, of an agency whether personal or institutional to which a leak could be referred or by which it could be claimed — is essential to the feel of the leak as a genre, in its production of migratory embarrassment. Lodging nowhere specific, caused by no motive in particular, embarrassment roams and surveys a wide field of actors.

As it became encoded in the leak, embarrassment not only brought a genre into existence but also distinguished that genre from other genres, such as the "plant" or espionage. Opinion writers were quick to point out the hypocrisy of attacking the Times for publication when "Government officials 'leak' classified information every day — Presidents and Cabinet officers have been known to do it"; "it is ridiculous to consider steps against press publication of classified documents while Government officials are permitted to rush into print with memoirs quoting secret papers."54 The point was brilliantly parodied in a June 20 editorial that came in the form of a story in which Pentagon officials in the "Office of Overt Graduated Document Leakage" are frantically trying to get a classified document published in order to influence Congress but no journalist will take it for fear of prosecution.55 But what made the Pentagon Papers seem different from previous plants of single documents or memoirist disclosures of single quotes was, of course, its archival volume, and the embarrassment of having lost so much volume at once. When Judge Gurfein, in his District Court opinion, remarked that "any breach of security will cause the jitters in the security agencies" and acknowledged "the general embarrassment that flows from any security breach," he similarly participated in an orientation to form over content: any leak will be embarrassing by the mere fact that it is indeed a leak.56

The development of an affective consensus around leaks also differentiated the Pentagon Papers from previous government disclosures, such as the first case in which a government employee was federally prosecuted for a leak, fifteen years prior. Before there was Ellsberg, there was Colonel John C. Nickerson, Jr., who supervised the U.S. Army's Redstone Artillery Range in Alabama and leaked a memo he had written reporting on promising developments in the design of inter-continental ballistic missiles. Nickerson had been outraged when, in November 1956, the United States Secretary of Defense had decided the Army would pursue developing only short-range missile technology, delegating long-range development and, consequently, a great deal of actual and cultural capital to the Navy. His leak to the author of the rumor mill column "Washington Merry-Go-Round," Drew Pearson, was intended to reveal the actual superiority of Army initiatives, perhaps in retaliation against someone who was technically his boss for what Nickerson deemed technically a demotion. But when Pearson corroborated the memo with the Department of Defense, Nickerson's role in disclosing classified information — results of secret missile tests — came to light, and Nickerson was promptly arrested.

Nickerson was not the first government official to disclose privileged information to journalists, nor was he the first to do so primarily as a result of personal grievance; indeed, the so-called "Coolidge Committee," officially the Department of Defense Committee on Classified Information, had released a report on November 8, 1956, summarizing multiple cases in which the parties responsible for disclosure were primarily "motivated by a desire to further the interests of a particular Service." Commenting on the Department's relative immaturity — it was founded only nine years prior but tasked with the enormous task of supervising all the armed forces and services — the Committee expressed an anxiety "that loyalty to a Service has a greater appeal to the individual [employee], since it is rooted in years of tradition, than does loyalty to the comparatively recently created Department of Defense."57 Its proposed solution to employees releasing information for the good of their division but the bad of the Department entire was to seriously ramp up consequences for disloyalty. Nickerson's case, which emerged less than three months after the Committee's report, was the first in which this was put into practice. The tool the government deployed was the Espionage Act of 1917, which Lloyd Gardner has called the "weapon of choice against leakers." The logic of this Act — the kind of "profiling" of people it makes available — is the "assumption that an opponent of any government activity must be a foreign agent": Nickerson was disloyal to the Department of Defense; therefore, he is a spy.58

Nickerson was the first leaker to be prosecuted under the Espionage Act; every leak prosecution since, especially in the explosion of prosecutions under President Obama, has been through the Espionage Act. (The government tried to jail Ellsberg, too, under the Act, but his case was thrown out after it was revealed that Nixon had hired CIA agents to ransack the office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist.) Provoking the Espionage Act but featuring a United States government official rather than a foreign agent, Nickerson's case is both more prophetic and more representative of the ways in which leaks would enter into legal frameworks in the late 20th century. But, as recent commentators have noted, Nickerson's case has been largely overlooked in histories of leakers.59 Perhaps one reason is that the case doesn't feel like a leak. The contents of the leak (intercontinental ballistic missiles) in addition to the legal framework in which it was presented (the Espionage Act instead of the 1st Amendment) are more suggestive of the genre of the spy novel than the genre of the leak. It is a case that belongs more to a Cold War narrative of technology than to a late twentieth-century story of governmental or bureaucratic weakness. Indeed, what Nickerson leaked was that the military was even stronger than the government was letting on: Nickerson's complaint was that the Army was not getting enough credit, or enough resources, to make its missiles fly even further than the 3,000 miles they already did. This is not a story in which a government comes out embarrassed, and without someone being embarrassed, it doesn't feel like a paradigmatic leak at all.

In memos regarding the Nickerson case, reference to a "leak" always comes in scare quotes. So, too, during the first days of publication of the Pentagon Papers fifteen years later, the word "leak" itself shows up only rarely and always in quotation marks, which contain its metaphorical nature. In the early District Court opinions of Gurfein and Gesell, leak and its conjugates — leaked, leaks — are also set off with inverted commas. The presentation of the word in this fashion suggests that it was neither a new word at the time (the Oxford English Dictionary cites the verbal sense of "an improper or deliberate disclosure of information" dating back at least to 1859), nor a fully assimilated one. But just as a foreign word may lose its italics as it becomes more familiar within an adopting language, "leak" lost its quotes by the end of June 1971, suggesting not only the descent of a metaphor into a concept but an anticipation of repetition.60 In other words, the compressed discourse of the last two weeks of June — a rapid succession of court opinions, published in part or in full in the Times and accompanied by opinions from officials and non-official citizens alike — incubated an emerging definition of the leak, triangulated by a shift from security to interest and from immediate to irreparable harm. By June 30, the leak had emerged as a commonsense genre that related a reading public to a desiring nation imagined as embarrassingly incontinent.

An Embarrassing Genre: Leaks in Institutions and Infrastructures

The major transitions codified by the leak genre — from physiological to psychological sovereignty; from identification with the state to a differentiation of personal from national interest; and from the leak as a primarily epistemological to a primarily affective norm — are dramatized in American cultural allegories of "leakiness" beyond but contemporary with the bureaucratic scene. In the century before the Pentagon Papers, the genre that the word "leak" was most likely to summon in the popular American imagination probably belonged to the children's tale of a boy who saves Holland by plugging a leak in a dike with his finger, widely popularized as a story told within Mary Mapes Dodge's bestselling 1865 novel, Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates. Dodge did not come up with the story, but neither did it originate in the Netherlands; in the United States, where the tale became canonical folklore, it was published at least as early as the August 1850 issue of Harper's. In Dodge's version, an unnamed boy, whose father supervises the gateways regulating water in the canals around a city in Holland, is on his way home when he notices "a leak in the dike," the thought of which "any child in Holland will shudder at," for "[e]ven the little children in Holland know that constant watchfulness is required to keep the rivers and ocean from overwhelming the country."61 The leak in the dike is one of the only italicized phrases in the story; another is a reference to "the angry waters" that the dikes keep out. The boy has learned this phrase from his father ("I suppose he thinks [the waters] are mad at him for keeping them out so long," he speculates), and he repeats it to himself when he plugs the leak with "[h]is chubby little finger" and thinks, "the angry waters must stay back now!"62 On first glance, a story about a boy contributing his body — whose corporeality is accentuated by the finger's chubbiness — to the defenses of a region would seem a direct allegory of biopolitical sacrifice in the name of national sovereignty. But the story complicates the allegory by referring so insistently on affect: before he encounters the leak, the story gives us the boy's "gentle disposition," his "light heart," his "careless" cheer, and these are all mirrored in the cheer of a sunny landscape exhibiting the country's flowers. It is not just that the waters threaten to end life in the country, but also that their anger threatens to "overwhelm" the mood of the boy and of the country in which he resides. The story imagines a land whose borders must be protected not from, say, the encroachment of other states, but from aggressive affect.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UR9ePwukzMc

A Leak in the Dike (dir. Jack Mendelsohn, 1965)

Phoebe Cary's poetic adaptation, published a decade after Dodge's novel, changes some of the story's details — the poem gives more attention to the mother of the child, whom it also gives a name — but it retains the affective encoding of the sea, which is "wicked" and "cruel" and threatens to let loose "its angry might."63 More recent adaptations, however, have let this anger drop. Just a few years before the Pentagon Papers, Jack Mendelsohn's comic short animation for children, "A Leak in the Dike" (1965), does not even make reference to the boy's affective disposition, only talking about his physiological "cold and exhaustion" while waiting for relief from keeping his finger in the dike. Furthermore, the boy hesitates before submitting his body to the defense of the state: he imagines the flood sweeping away his school, his teacher comically providing a lesson on how to spell help ("H-E-L-P: HELP") from the top window. This apparently desirable outcome encourages to the boy to "mind his own business" and continue going his merry away along the dike. Only after further reflection, when he realizes not just the school but the entire city will be put underwater, does he finally come humbly to the rescue. In this rendition of "Leak in the Dike" contemporary with a leak in the Pentagon, a gap is opened up between the personal interests of the boy and the governmental interests of the nation in which he resides. In the previous century's Hans Brinker, the story is told in a classroom, in turn imagining a situation in which the school as an institution mediates a sense of belonging to a larger state identity and interpellates a young citizenry into patriotic service. Dodge provides a commentary on the story by way of the classroom's teacher: "that little boy represents the spirit of the whole country. Not a leak can show itself anywhere either in its politics, honor, or public safety, that a million fingers are not ready to stop it, at any cost."64 But in Mendelsohn's cartoon, affective sublimation is not so easy: the hesitance introduced between problem and action embellishes the gap between personal and national interests. The individual owners of the "million fingers" first ask themselves what they want and then ask if that is what the nation wants, too. The cultivation of the nation as a desiring figure, as a type of person, invites real persons to ask whose desires are more legitimate.65 In turn, rather than imagine a state in which everyone has the same interests and therefore only need to be protected from negative affect beyond the state's borders, here contradiction and dissent are already interior to the nation.

The conception of the state as a desiring subject enables citizens to develop a relation with the state as one of intercourse rather than identification: the state becomes a person with whom one interacts as a lover, rather than identifies with as a body. This archive of leaky dikes also brings out a trajectory of anxieties about the role of the citizen in the maintenance of state institutions and infrastructures. The failure of the boy's school to program immediate allegiance to state infrastructures is similar to the Pentagon's failure to discipline Ellsberg — or, more recently, someone like Edward Snowden or Chelsea Manning — into keeping hold of its intelligence. Moreover, there is a formal similarity between institutions that cannot keep in their secrets and infrastructures that cannot keep in their resources.

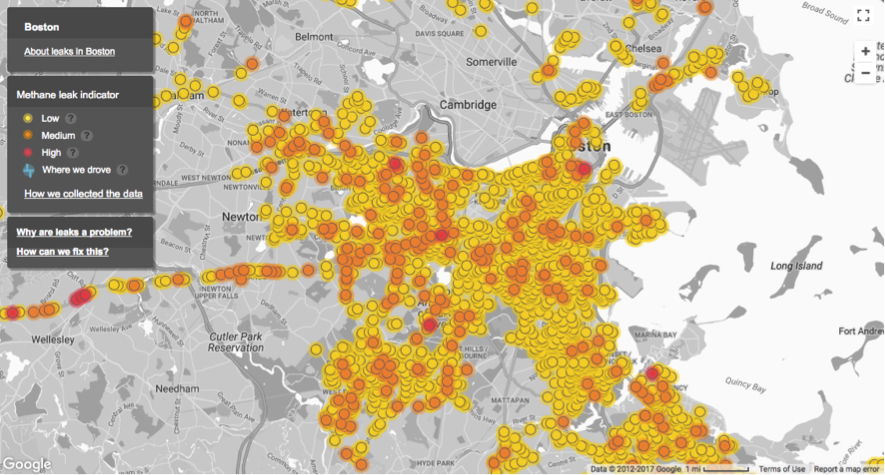

In January 2016, two technically unrelated but thematically similar states of emergency were declared in the United States. The first, in Flint, Michigan, was the culmination of two years during which lead had leached into a local water supply. The second, in the Porter Ranch neighborhood of Los Angeles, California, concerned a leak of natural gas out of a Southern California Gas Company storage facility. It would become the largest natural gas leak in American history. Both cases were and are spectacles of decaying or mismanaged infrastructures of pipes and containers that were meant to keep toxic materials out of human circulation. They also called attention to the pervasiveness of environmentally dangerous leaks throughout the country. In 2014, the Environmental Defense Fund partnered with Google Maps to present interactive maps "to find and assess leaks under our streets and sidewalks." In cities, the dots indicating sites of minor leaks are so numerous, the entire municipality is covered. In Los Angeles, EDF found one leak every four miles; in Chicago, every three miles; in Boston and Staten Island, every square mile has a leak. Their density is correlated with the age of piping infrastructure; in Boston and Staten Island, more than half the pipes are more than half a century old.66

The Environmental Defense Fund's interactive map of gas leaks in Boston visualizes infrastructural decay in a city where the majority of gas pipes are over 50 years old.

We live in an age of everyday leaks: political, informational, environmental. Massive events from WikiLeaks's "Collateral Murder" to Porter Ranch concentrate and highlight an even more common condition of both secrets and natural resources being shared and aired: their non-singularity, their regular and recognizable frequency. This regularity is one of the things that leaks of information and of natural resources, otherwise seemingly different phenomena linked only by the coincidence of a common word, have in common. Another is their indexing of institutional and infrastructural decline: the ways in which bureaucratic institutions cannot keep in their data just like energy infrastructures cannot keep in their resources; the ways in which data and resource storages are both constantly breached. The story of leaks is, according to one commenter on the Flint and Porter Ranch disasters, "the story of a government unable or unwilling to protect its citizens from basic infrastructure malfunctions, of regulatory bodies so fractured that no responsible party emerges."67

The emergence of the leak as a genre — which is to say, not only the increasing frequency of leaks in both infrastructural and institutional contexts, but also the creation of norms and expectations for what leaks are, how they are caused, and what they mean — marks the creation of a space in which national subjects process the failures of their national government to provide strength of security, whether of intelligence or of resources. The dynamics of this regularized disappointment are further illuminated by viewing leaks from the perspective of other genres, in line with Wai Chee Dimock's call on us to study genres in relation to other genres: "the concept of genre has meaning only in the plural."68 At the time of the Pentagon Papers, I considered the leak in relation to the genres of government memos and the spy thriller. More recently, we can imagine a "pool" (Dimock's image) in which the leak also swims alongside such genres as conspiracy theory. In his introduction to Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan's monograph on the history of secrecy in American national security politics, for example, Richard Gid Powers notes that a mainstream routinization and banalization of the revelation of secrets developed in parallel to the story Moynihan tells of the routinization of secrecy during the Cold War. With the advent of widespread conspiracy theory (think of the popular armchair practice of theorizing the JFK assassination) and an entire culture industry trained on the allure of government mystery (think The X-Files), secrecy "evolved from a theme in historical analysis to the status of an aesthetic formula and plot concoction."69 This formulization of secrecy has also enabled the genre of the leak to be absorbed within the genre of the novel, in the case of Purity. Reading the leak through the novel therefore helps to exemplify the contours of a formula for leaks by considering what information the novel feels compelled to offer and what information or sets of expectations it assumes readers come equipped with already. By providing a context for the genre within a larger discursive universe, the novel also maps out the leak's extra-generic thematic affiliations.

Perhaps the most important thing Purity tells us about leaks is that leakers have their secrets,too, and these are paradigmatically sexual. When Pip, one of the protagonists of Purity, tells her mother she is going to go work for Project Sunshine, she mistakes it for WikiLeaks: "That is the group that the sex criminal started" (71). She is thinking of Julian Assange, who is still under question for a series of sexually related crimes, including rape, in Sweden. The novel's fascination with Andreas Wolf's story is similar to the real-world public's fascination with Julian Assange, and it turns out they have a number of things in common in addition to their trisyllabic first names, one starting off where the other ends (Julian, Andreas): they are both white foreign nationals (Assange from Australia, Wolf from Germany); they are both straight; and although Andreas is not accused of rape, he does have a sexually suspicious past. While living in East Germany during the Cold War in his late twenties, he counsels troubled or runaway youths from the basement of a church; they are often teenage girls and he not infrequently sleeps with them. One of the girls, he learns, is being sexually abused by her stepfather, a Stasi informant; concluding that the state will be unresponsive to her needs, Andreas schemes with her to kill him. This scheme might have been the seed of a desire for vigilante justice that, alienated from the state, culminated in a campaign of leaking state secrets, but we eventually learn that this, in itself, is not what led Andreas to found Project Sunshine. The path to revolution is instead more accidental and self-serving. Years later, just after the Berlin Wall has fallen, Andreas fears that the people will eventually claim his file in the Stasi archives, thereby making known his crime; he leverages his own stepfather's power in the Socialist party to get into the archives and steal his own file, and when he flees the building, he encounters television cameras and pretends, as an alibi, to be a dissident committed to bringing all the Stasi files into the "sunshine." Andreas eventually brings about a similar reversal on a larger scale: a transition from a period in which the state has a physical file on everyone to everyone having a virtual file on the state.70

The affective underpinnings of this transition are predicated on the end of the Cold War. John Lewis Gaddis has remarked on the decreasing viability of a global containment strategy — explicit in the national security memos of George Kennan and the NSC-68, as discussed in the previous section, and implicit in the government's argument against the publication of the Pentagon Papers — in a post-Cold War era. Containment, and with it, an investment in the psychological in addition to physical health of a nation, presumed a system of war between states that shared a sense of risk, an increasingly irrelevant condition when it comes to transnational terrorism. But more importantly, the strategy presumed that America's legitimacy in the world could also be put into relief by comparison to some other, greater state evil: at least the USA is better than the USSR, this line of reasoning goes. Absent this competition between great powers, "the basis for American power will [shift] from invitation to imposition."71 What Gaddis says about waning national legitimacy in the international theater can be said domestically, too: with the decline of a bipolar international order and a clearly outlined and bordered state threat, citizens, too, no longer feel compelled to invest in a national form as a guarantor of their protection. The end of the Cold War is also the diminution of a fantasy that national interest, national security, and a national affective consensus could be aligned. Here, a citizen does not have to be embarrassed by the embarrassment of his state; indeed, embarrassment of the state may be a relief from being embarrassed one's self.

The transference of embarrassment is part of what makes the leak an unsurprising genre: a genre whose contents are already known and therefore unable to change the world. In order not to be embarrassed by the state, Andreas actively embarrasses the state; he takes a position as the people's spy in order not to be caught spied upon. What Purity thereby suggests is that the primary affective affordance of the leak — its migratory embarrassments — is intimately part of the other affective response that finds, in advance, the content of leaks to be so unsurprising: stoicism. To know already what a leak contains — or even, hermeneutically, what it means — is to defend against the accusation that the reader is the party embarrassed, for having previously been duped. The leak as a genre draws from a world in which paranoia is the new normal, in which people already believe the United States government has killed innocents or Hillary Clinton has abused her power, and in which clicking on a headline is only to confirm what you knew all along.

It matters, I have suggested, that Andreas does not just have a secret, however, but a sexual secret related to statutory rape. If Purity were not a novel in which WikiLeaks is mentioned as a competitor of Project Sunshine, we might have thought Andreas was supposed to be a stand-in for Julian Assange; instead, their similarity suggests the emergence of a convention, the bringing into proximity of leaking and sexuality. Purity suggests one reason why the two go together by staging sexual scenes as a mediation of secrecy. The eventually murdered stepfather originally entraps the daughter by shaming her for his own advances on her: "And now we have secrets together. Just you and me. Can I trust you?" (93). Andreas repeats this logic when he makes a move on Pip, touching her genitals: "Is this not a private thing of yours?" (276); "I want us to trust each other" (277). Pip consents, and being in on a private secret increases her pleasure as he goes down on her: "He seemed honestly to want her private thing. It was really this knowledge, more than the negocitos he was expertly transacting with his mouth, that caused her to come with such violent alacrity" (278). Sex binds people in Purity in common privacy with private secrets; it is what keeps people on the same side in an ever-shifting business of revealing the secrets of others. Or more thickly: if the leak is about shame and embarrassment, it becomes associated for many people with an essential scene in which these affects were first experienced, namely the sexual. Embarrassment brings the genre into the realm of sexuality.

The sexualization of secrecy in proximity to the leak is not unique to this novel; it is part of the genre of the leak, for instance in other fictional representations of the sharing of governmental secrets including the critically acclaimed Netflix series, House of Cards. In the first season of that series, the protagonist, an ambitious member of the House of Representatives, is able to trust the reporter to whom he leaks secrets in part because they share a sexual contract. She offers to let him take nude photographs of her ("the type my father wouldn't want to see"), the assumption being that her vulnerability to embarrassment is reciprocal to his vulnerability to treason. At one late night rendezvous, she remarks the arrangement is "very Deep Throat of you," citing the primary precedent for the sexuality of leaking: the source of the Watergate scandal in the year after the Pentagon Papers, whose codename was borrowed from the title of the pornographic film that was immensely popular the same summer the scandal unfolded (the movie was released on June 12, 1972; Watergate was broken into on June 17). In their recounting of that summer, Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward comment on the origin of the alias as a play on "deep background," which is "newspaper terminology" for information from an anonymous source that the journalist uses to contextualize a story without publishing.72 But they also acknowledge the name was intended to sexualize the source and in any case it highlights the erotic nature of the informant/journalist relation. Woodward explains how he communicated with Deep Throat through moving curtains and pots in his apartment; in other words, the condition of having the source was that the source was spying through his bedroom windows. The film adaptation of the Bernstein and Woodward memoir, All the President's Men, shows Woodward in shadowy and sometimes breathless talk with his source late at night in empty garages; his editor calls the source not only Deep Throat but also Garage Freak, suggesting sexual in addition to bureaucratic perversion. In the pornographic film, deep throat is the name of the sexual technique the protagonist, whose clitoris is in her throat, masters in order to achieve sexual pleasure; in All the President's Men, giving information is like giving head.

Many of the most visible leaks of the past decade, in and out of government, have been explicitly about sex. The Ashley Madison leak of 2015 provided e-mails registered on the website primarily designed to enable extramarital affairs; in a related attack on privacy with the seemingly sole intention of embarrassment (rather than, say, financial gain either through sale or through blackmail), the year before had seen the leaks of private photographs from the iCloud accounts of several celebrities in what came to be called the "Fappening," after the word "fap" for masturbation. Sex is embarrassing; leaks are embarrassing; leaks are sexy. Thus, public discussion of the so-called "Trump dossier" written by former MI6 agent Christopher Steele about possible collusion between Russia and the Trump campaign in the 2016 presidential election and published by BuzzFeed in 2017, inevitably focused on allegations that Trump had hired sex workers to engage in "perverted sexual acts," primarily urination, in a Moscow hotel room. The idea was that this non-normative sexual behavior would be so shameful the Russian government could blackmail Trump with evidence of it.

In response to the sexual economy of embarrassment, a frequently immediate but usually unviable response by the party aggrieved by a leak is to try to move the shame around by digging up dirt, again of a typically erotic variety, on the leakers themselves. In the aftermath of the Pentagon Papers, Nixon's White House Plumbers (where the colloquial idiom indicates a further turn on the absorption of the leak as a commonplace in American discourse) raided the office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist, presumably looking for embarrassing information about him that Nixon could leak in retaliation. Ironically, this gross criminal activity would eventually lead to Ellsberg's prosecution being thrown out of court. In more recent years, discussions of WikiLeaks have often been focused not only through the sexual crimes of Julian Assange, but also the sex and sexuality of Chelsea Manning, even before she came out as transgendered. The Public Broadcasting Company's hour-long Frontline special WikiSecrets (2011), for instance, was criticized for spending more of its time on Manning than on WikiLeaks, foregrounding a sensationalist account of its most visible whistleblower and contributor rather than WikiLeaks's politics. The documentary spent more than ten minutes discussing, not Manning's dissident activities or resulting imprisonment, but her family life: how she had been teased as a boy by other classmates for appearing too feminine or how she had been, according to her interviewed father, "spoiled rotten by his mother."73 In retaliation, LulzSec, an offshoot of the larger hacker collective Anonymous, announced on Twitter they had "decided to sail our Lulz Boat over to the PBS servers for further ... perusing."74 They proceeded to post personal information — mostly website logins, e-mails, and passwords — of PBS employees and station staff. This back and forth on the exposure of personal information is part of the logic of power in a leaky discursive environment, a tug of war over the place of embarrassment.

Part of what is going on here is, as Russ Castronovo has described it in his deflationary account of WikiLeaks, is a consolidation of new forms of networked agency into liberal subjects so that the biographies of Ellsberg or Assange or Manning come to stand in for the political programs or technology platforms in which they participate.75 The individualization of anonymous collectivity has been further exacerbated by the tendency of many documentaries to reduce ethnography of a group to a profile of a person, for instance in Silenced (2014), The Hacker Wars (2014), and The Internet's Own Boy (2014). In the Academy Award-winning documentary about him, Edward Snowden remarks on camera, "I feel the modern media has a big focus on personalities, and I'm a little concerned the more we focus on that the more they're going to use that as a distraction ... I'm not the story here"; but he is, indeed, the story of Citizenfour (2014). The point is brought home in the dramatic adaptation of his career, Snowden (2016): Glenn Greenwald opens his interview with Snowden by asking him to "tell us why you did what you did and how you came into contact with such vast amounts of information," but his research companion Laura Poitras (who made Citizenfour) interjects, "How about we just start with your name?" If Snowden had answered the first question, the film would have been about the disclosure of "vast amounts of information"; instead, the film proceeds to tell the life story collected under the proper noun of "your name." Oliver Stone, the director of Snowden, drew some inspiration from Time of the Octopus, a fictionalized account of Snowden written by his lawyer Anatoly Grigorievich Kucheren; Stone liked that the novelist "weigh[ed] the soul of his fictional whistle-blower."76 But such a weighing of the "soul" introduces into the relation between leaker and the leaked the possibility of a relationship of shuffling embarrassments and shame. If, in Foucault's disciplinary society, one is always compelled to confess one's soul, understood as essentially one's open secret of sexuality, then the society of today sees a contract by which confession is no longer coerced but extracted through a leak, and with it, a rehearsal and re-appraisal of sexually coded shame.77

In Purity, the sexualization of the story might be owed partly to the genre of the novel, which is attracted to the inner lives of characters (think Virginia Woolf's famous line that novelists write in order to chase and catch a character) more than the inner workings of bureaucracies and which is thereby predisposed to unfold sexual drama in order to have, precisely, drama.78 Halfway through Purity, Pip exclaims to a couple providing her housing that she would never read their personal e-mails because they "are my heroes. I would never spy on you" (313). But a novel often does precisely that: it spies on its "heroes," giving readers more access to their thoughts than we could ever have of another person in the non-fictional world. In turn, Purity risks, like PBS's WikiSecrets, psychologizing and thereby dismissing political action: Project Sunshine becomes merely "an extension of [Andreas's] ego" (450): "I'm not doing this job because I still believe in it. It's all about me now. It's my identity" (275). This is a novelistic liability, although, as we have seen, the individualizing of collective action is not unique to the novel genre.79 At the same time, Purity is registering a larger social fascination with leaking as an erotic genre, with secrecy coded as sexual and therefore leaking as a mediation of a sexual relationship between a public and its government.

On the one hand, this is familiar idiomatic territory: Andreas's "penetration" of the Stasi archives, for instance. But leaking picks up on something more fundamentally sexual as well — something about the experience of sexuality that is more abstract than the sex act itself. There is something uncontrollable about leaking that is akin to the loss of control in the jouissance of sexuality. Purity registers this ejaculatory nature of personal leaking: Pip gives "Outburst Alerts" for her oversharing (302); she wonders, while spilling her personal data, "Where were these words coming from? What hidden place?" (51). The characters of Purity find themselves in a situation in which the government does not need to have a file on them because they write and publish their own files on Facebook, detailing not only the events and actions they undergo and perform, but also their feelings in relation to them. The characters of the novel claim to want privacy but they also want the world to know what they are feeling at this very moment; one of the fundamental ambivalences of the world registered by the novel is the simultaneous paranoia of thinking the government is spying on you and knows all your secrets and the pleasure of thinking your secrets are worth knowing, that the government cares. It is not just that people enjoy learning that a corporation with a master plan or a state with an imperialist agenda has leaked because people want to take preemptive revenge for maybe being leaked themselves: the joy of being the spy instead of the spied upon. It is rather that people want, irreconcilably, to be both. Andreas comments on this fundamental ambivalence in his "theory of secrets": "There's the imperative to keep secrets, and the imperative to have them known" (275). People want to keep secrets but also, as Laura Kipnis has suggested, cannot help but spill their secrets.80 This spilling is full of pleasure; Purity calls it an explosive "relief" (461). But it is a relief that must be disavowed by the competing "imperative" to keep the secrets in.

In a different national context, Lisa Wedeen has unfolded the "cruel optimism" of a public's desire for sovereignty projected onto a sovereign who reduces public flourishing. In this national fantasy work, people buttress the sovereignty of a leader in order to fantasize it as their own.81 At first, leaking might seem to oversee the reverse affective transferal: a people who embellish the vulnerability of their state bureaucracies in order to relish in the joy of lost control by proxy. But this would only bring into relief the inadequacy of both accounts in attending to the ambivalence underlying every fantasy, and national ones in particular — the inadequacy to account for the fact that people want to feel both sovereign and nonsovereign, to be both powerful and out of control. Perhaps what is terrible to some people is not feeling nonsovereign, but feeling ambivalent, split between wanting two contradictory things. This is the point Leo Bersani made in a famous but not infrequently misunderstood definition of "the sexual" as "moving between a hyperbolic sense of self and a loss of consciousness of self": pleasure both inflates and erases the self, and so the self, supervised by sexuality, is by definition split into warring parts.82 What Bersani then proposes is that this internal war is so unbearable that the self tries to identify with one of the parts instead of holding together its contradiction, and its strategy for doing this is to introduce another person to implant its disavowed part into. Sexuality moves from masturbation to intercourse so that a one-body problem can find a two-body solution: the self can fantasize that, rather than being singularly contradictory, it participates instead in a complementary couple. Of course, violence is sometimes required to administer the proper roles; Bersani suggests "it is ... the degeneration of the sexual into a relationship that condemns sexuality to becoming a struggle for power."83