Issue 2: How To Be Now

In 2015, three governing bodies of Anglo-American language studies — the American Dialect Society, the Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary, and the Oxford English Dictionary — attracted unusual attention when they announced their respective Words of The Year. None of them could be called, by our usual measures, a word. This was perhaps to be expected. The election of one word to encapsulate a year is a relatively new phenomenon, after all. While the German "Wort des Jahres" originated in 1971, the English-language Word of the Year (or WOTY, as it's abbreviated) first appeared in 1991, determined by a vote of independent linguists belonging to the American Dialect Society. A WOTY is meant to register how culture is changing and what neologisms have been invented to accommodate it, and this drift toward novelty would seem inevitably to lead to "words" beyond the remit of conventional language. Yet the common recognition of each of these curious non-words in 2015 indicates an even deeper shift in the culture, what I would describe as a contemporary ambivalence about the relationship between the singular and the plural.

The American Dialect Society's Word of 2015 was selected in January by a group of 200 linguists. By a vote of 187 hands, the society voted for "they."1 "They" is a real word, of course, though a frequently used pronoun would seem too generic to reflect an entire year. But the Society voted specifically for its usage as a gender-neutral singular pronoun for a known person, that is, as a non-binary identifier. This means "they" can be substituted for "he" or "she" as a singular noun — a grammatical oddity, a seeming sacrilege, even for a society of linguists committed to dialect. At the time, news of this choice induced as many shudders and eye rolls as nods and smiles. But as Bill Walsh, the copy editor for the Washington Post, noted, it is indeed "the only sensible solution to English's lack of a gender-neutral third-person singular personal pronoun."2

The Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary went beyond unusual usage and chose a suffix to represent 2015: "-ism." The selection process for this half-a-WOTY was more statistical than democratic: "A suffix is the Word of the Year because a small group of words that share this three-letter ending triggered both high volume and significant year-over-year increase in lookups at Merriam-Webster.com."3 Taken together, seven words represented millions of individual searches on the site: socialism, fascism, racism, feminism, communism, capitalism, and terrorism. While these words give us an apt index of the topical political issues of 2015, their shared suffix -ism also suggests a numerical ambivalence analogous to the singular pronoun "they." An "-ism," when used as a noun, can mean "a distinctive doctrine, cause, or theory" or "an oppressive and especially discriminatory attitude or belief."4 Its distinctive or especial quality is key. But lay usage of "-ism" often pluralizes and groups it, as in the Medium article: "There Are Too Many Isms In Art And I'm Tired Of It."5

The WOTY "-ism" possesses a grammatical oscillation between the singular and the plural, and a semantic oscillation between the particular and the general. Further, many of Merriam-Webster's frequently searched terms are precisely about the relation of the individual to the collective—"socialism," "fascism," "communism" "capitalism." Others more mundanely exhibit the difficulty of distinguishing "a racist" from "racism" or "a feminist" from "feminism" in everyday discourse, especially online. Both of our WOTYs so far — "they" and "ism" — thus muddy distinctions that seem key to signification in the English language as such: male and female (gender); the one and the many (number); the specific and the general (indexicality).

The 2015 selection by the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) did away with the word altogether:

This pictograph is technically known as the "Face with Tears of Joy" emoji.6 The press release on the OED Blog was rather self-congratulatory about this oxymoronic WOTY:

That's right — for the first time ever, the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year is a pictograph: the 'Face with Tears of Joy' emoji ... There were other strong contenders from a range of fields ... but Face with Tears of Joy was chosen as the 'word' that best reflected the ethos, mood, and preoccupations of 2015 ... Why was this chosen? Emojis (the plural can be either emoji or emojis) have been around since the late 1990s, but 2015 saw their use, and use of the word emoji, increase hugely. This year Oxford University Press have partnered with leading mobile technology business SwiftKey to explore frequency and usage statistics for some of the most popular emoji across the world, and Face with Tears of Joy was chosen because it was the most used emoji globally in 2015. SwiftKey identified that Face with Tears of Joy made up 20% of all the emojis used in the UK in 2015, and 17% of those in the US: a sharp rise from 4% and 9% respectively in 2014. The word emoji has seen a similar surge: although it has been found in English since 1997, usage more than tripled in 2015 over the previous year according to data from the Oxford Dictionaries Corpus. Emojis are no longer the preserve of texting teens — instead, they have been embraced as a nuanced form of expression, and one which can cross language barriers.7

This explanation proffers various forms of legitimacy for the choice: relevance, popularity, adult use, nuance, and portability. Note that these last two justifications taken together reveal the same tension in the other two WOTYs: nuance suggests particularity, a desire to pinpoint the exact signification, while cross-linguistic communication suggests generality, if not universality.

The emoji, as a pictograph or "word-picture," encapsulates what we might call, quasi-mathematically, a set theory problem of contemporary communication. That is, if we translate the question "what is the relation between an object and its set?" to language, we might ask instead: what is the relation between a word and its language? Or, more broadly, what is the relation between a sign and other signs of the same kind? If we take emoji as a case study, what is the relation of the Face with Tears of Joy emoji to emoji as such? Is the OED's choice of this emoji for WOTY meant to suggest a specific idea — 2015 is the year of crying through laughter or laughing through tears — or does it simply index the appearance of "a new kind of word, the emoji"?

This is, again, a specifically contemporary question about the relationship between the singular and the plural. Highly tied to context and transmission yet transparently generic, the emoji signifies each instance of its use and all its other instances of use and all its other uses and all the other emoji. This WOTY doesn't just require a reconsideration of signification as such; it also offers an example of the distinctly contemporary relation between the individual and the collective, and what I will call the pleasurable and potentially political affordances of that ongoing dialectic.

Cognitive psychologist James J. Gibson coined this term in the 1960s to describe how organisms relate to their surroundings: "The affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill."8 Scholars in design, linguistics, media studies, and phenomenology have since adapted the concept. Donald Norman defines it thus in his 1988 The Psychology of Everyday Things: "the term affordance refers to the perceived and actual properties of the thing, primarily those fundamental properties that determine just how the thing could possibly be used. A chair affords ('is for') support, and, therefore, affords sitting."9 Eleanor Gibson first applied affordance to the process of reading in her The Psychology of Reading (1975); Caroline Levine's Forms (2015) and my Seven Modes of Uncertainty (2014) both elaborate on its use for describing an interrelation between reader and object that ascribes intention and priority to neither.

In what follows, I attend to the affordances of the ontological ambiguity of emoji — as both singular and plural, word and picture. (I will use the plural form sans "s" — emoji — to emphasize the conflict internal to the word itself.) First, I offer a brief history of emoji as a form of communication that aspires toward the presumed authenticity, transparency, and intentionality legible in the human face. Then, I suggest that, despite the ubiquity of faces in contemporary media, emoji is in fact just as "faceless" as print language. While we might think this is because digital communication somehow evacuates meaning and motivation from language, emoji is simply an extreme case of the slipperiness and hollowness that inheres in signs as such. I then turn to some contemporary examples of emoji art, which draw our attention to emoji's affordances, not as a semantic vessel, but as an adamantly material sign with distinctive uses, dimensions, temporalities, and effects.

I posit that we compensate for the communicative lack in emoji through fetishistic play. The pleasure of emoji thus derives not from "clearer" communication, but rather from staggered and stacking effects that rely both on emoji's failure to communicate and on its singular/plural ontology. Ultimately, I suggest that this pleasure affords a distortion, exaggeration, and disruption of capitalist logics, though of course it cannot eliminate them. The emoji is a neoliberal fetish par excellence — signifying both endless proliferation and choice, while hiding the conditions of its production behind a contemporary hieroglyphics. Yet its availability for play is oddly democratic and its most successful appropriations have emerged not from high art but from marginalized groups in the U.S. like the black/queer community.

A Brief History of Emoji

An emoji is an ideogram or pictogram or pictograph — all four words are portmanteaus that gesture toward a long history of efforts to merge two different representational forms in order to improve communication. Let's consider the junctures that led to emoji as we now know it in the West: a tiny picture used largely in the context of social media and digital communication. None of these moments in emoji's history, which punctuate a span from the end of the nineteenth century to the end of the twentieth, can justifiably claim the title of an origin. To trace the scattershot history of emoji is to encounter the delights and the difficulties of many origins, many attempts to elide text and image in signs.

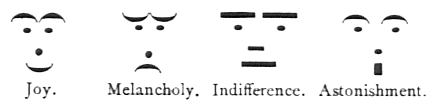

One origin of emoji is punctuation, often associated with a largely nonverbal medium: music. As Theodor W. Adorno notes in his charming essay, "Punctuation Marks," a punctuation mark taken in isolation acquires a "definitive physiognomic status of its own, an expression of its own."10 Take these oft-cited pictographs published in 1881 by the U.S. satirical magazine Puck:

The publication's letterpress department said they created these pieces of "typographical art" to "lay out ... all the cartoonists that ever walked."11 In 1912, Ambrose Bierce proposed "the snigger point, or note of caccination" — an upturned horizontal parenthesis to represent "a smiling mouth." Introducing the first of many calls for ways to signal irony, Bierce wrote that the snigger point ought to be "appended to every jocular or ironical sentence."12 Note that the punctuation symbols are reoriented to increase their visual resemblance to parts of the face. In a 1936 Harvard Lampoon article, Alan Gregg proposed (-) for smile, (--) for laugh ("more teeth showing"), (#) for frown, and (*) for wink.13

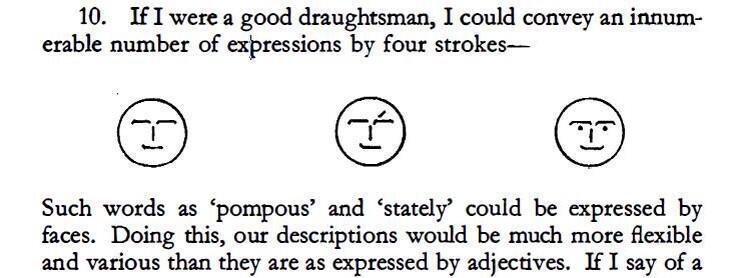

In "Lectures on Aesthetics," delivered at Cambridge in the late 1930s, Ludwig Wittgenstein compares language to a "tool chest" full of different tools that are used in "a family of ways."14 Arguing that the problem with linguistics at the time was a focus on "the form of words" rather than "the use made of the form of words," Wittgenstein posits that language is actually an activity, like talking, writing, traveling on a bus, and so on.

In his first lecture, he notes that the words we use for aesthetic description, like "beautiful," "lovely," "good," or "fine," first emerge as interjections (abrupt remarks or exclamations), which children learn under specific conditions: "One thing that is intensely important in teaching is exaggerated gestures and facial expressions. The word is taught as a substitute for a facial expression or a gesture."15 Adults who "can't express themselves properly" continue to use words like "lovely" in this exclamatory way, in order to register, say, the character of a piece of music. Wittgenstein probes this tendency: "I might ask: 'For what melody would I most like to use the word 'lovely'? I might choose between calling a melody 'lovely' and calling it 'youthful'. It is stupid to call a piece of music 'Spring Melody' or 'Spring Symphony.' But the word 'springy' wouldn't be absurd at all, any more than 'stately' or 'pompous.'" Moving toward even greater precision, Wittgenstein asserts:16

I assume that Wittgenstein wrote these up on some kind of board. But, given that the published lectures were compiled from the class notes of multiple students, I wonder how exact these drawings are, and which of these faces is meant to signify pompous, which stately.

In 1969, Vladimir Nabokov made a similar (pompous and stately) claim for the precision and flexibility of a pictogram. To the admittedly absurd question, "how do you rank yourself among writers (living) and of the immediate past?" he responded: "I often think there should exist a special typographical sign for a smile — some sort of concave mark, a supine round bracket, which I would now like to trace in reply to your question."17 Well, why not just smile then, Uncle Vlad? Well, because this interview was not, in fact, in person; Nabokov insisted on conducting most of his interviews by letter, so keen was he not to speak "off the Nabo-cuff," as he put it. 18 For Wittgenstein and Nabokov, the desire for exactitude emerges out of a question about aesthetic judgment, but the turn to the typographical hopes for something closer to an expression of affect — something more "flexible and various," "some sort of ... mark" — that will be immediately understood, that is generalizable, that is better than language.

The idea that human facial expressions are recognizable and categorizable at all first emerged as a scientific concept in Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872). Nowadays, facial recognition is a well-studied developmental stage in babies. Neuroscientists have located a part of the brain, the "fusiform face area," that lights up when we look at faces.19 Recent studies have shown, however, that the average person correctly assesses another person's expressions (thinking, agreeing, confused, concentrating, interested, disagreeing) only 54% of the time.20 Despite the belief that a face is clearer than a word, there's more variation in what facial expressions mean across culture, gender, and individuals than we might imagine.

In the 1960s, another lineage of the emoji emerged, one that also capitalized on the faith in the face as locus of universality. In 1963, State Mutual Life Assurance Company of Worcester, Massachusetts hired an American commercial artist named Harvey Ball (I'm not making that up) to create a happy face "to raise employee morale." Ball spent ten minutes and State Mutual Life Assurance spent $45 on the design: a bright yellow background, black oval eyes, and a full smile with creases. It was imprinted on more than fifty million buttons.21 Philadelphia brothers Bernard and Murray Spain were responsible for popularizing the "happy face." In 1970 they seized on it for a campaign to sell novelty items — buttons, mugs, t-shirts, bumper stickers — emblazoned with the symbol and sometimes accompanied by the phrase "Have a happy day," which mutated into "Have a nice day." A Frenchman named Franklin Loufrani legally trademarked this design as the "Smiley" in 1972. Although it came before the digital revolution, the cartoony simplicity of this internationally iconic grapheme influenced the aesthetic of the emoji and its digital precursor: the emoticon.

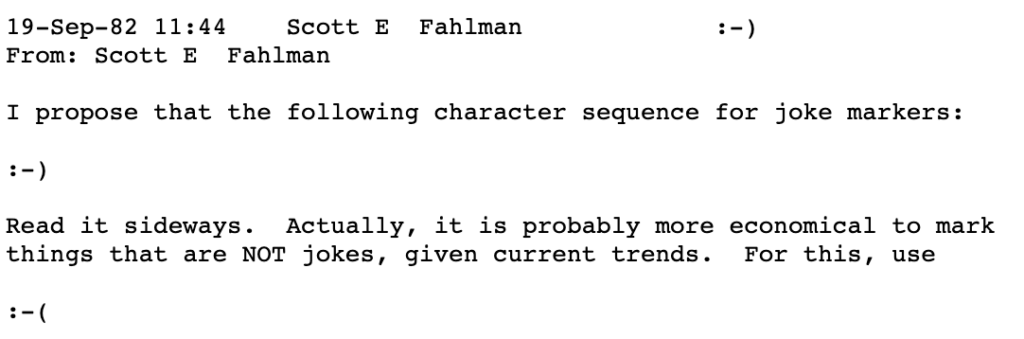

The word emoticon is a portmanteau of emotion and icon. Wikipedia defines it as "a pictorial representation of a facial expression using characters — usually punctuation marks, numbers, and letters — to express a person's feelings or mood, or as a time-saving method."22 The first digital emoticons were proposed by Scott Fahlman of Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on September 19, 1982, on a computer science message board:23

The desire for a punctuation adequate to the inflections of tone here is keyed, like Bierce's snigger mark and Nabokov's supine bracket, to the effort to signify irony.

While emoticons originally read sideways, a new horizontal format appeared in 1986: (*_*). Kaomoji emerged with the American Standard Code for Information Interchange, or ASCII NET. Kaomoji use carrots, asterisks, dashes, underscores, and parentheses to create faces that can be perceived without imagining tilting your head, like the Lampoon article I cited above. Often confused with emoji, kaomoji are strictly text-based, about a decade older than emoji, and etymologically distinct. The word kaomoji combines two words in kanji, kao (face) and moji (character), while the word for image-based emoji combines two words in Japanese, e (picture) + moji (character). (This means, by the way, that the e- in emoji has nothing to do with the electronic prefix e- in email nor with the affective prefix emo- in emoticon.)

In the late 1990s, a Japanese phone company, DoCoMo i-mode, noticed that mobile users were increasingly using picture messages, which are much larger files than text messages. DoCoMo's Pocket Bell pagers were especially popular because they had a heart symbol, and when a business-oriented pager was released that dropped the heart, there was an outcry among users, some of whom abandoned the company. To draw them back, DoCoMo engineers designed a set of commonly used pictures that could be added to text messages. Their innovation was to make these images into a single character, which was crucial back when text messages had character limits of 60-140.

This is the original set of 176 emoji, recently acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York:

One of the inventors of this first set, Shigetaka Kurita, explains the origin of the design:

I drew inspiration from marks used in weather forecasts and from kanji characters. At first there were about 200 emoji, for things like the weather, food and drink, and moods and feelings. I designed the 'heart' symbol for love. Now there are well over 1,000 Unicode emoji.... The introduction of the iPhone, whose users all have access to the same stock of emoji, has definitely been a great help. If they had continued to develop differently depending on the device, then I don't think they would have become as ubiquitous.24

On one hand, Kurita makes a claim for the emoji's directness and universality:

I don't accept that the use of emoji is a sign that people are losing the ability to communicate with words, or that they have a limited vocabulary. Some people said the same about anime and manga, but those fears were never realised. And it's not even a generational thing ... People of all ages understand that a single emoji can say more about their emotions than text.... I accept that it's difficult to use emoji to express complicated or nuanced feelings, but they are great for getting the general message across.25

On the other hand, he predicts that emoji will naturally progress toward greater specificity: "I think the next step for emoji will be more localisation. There are already lots of symbols that are specific to Japanese culture and society, and I expect the same to happen in other countries."26

The transition from emoticon to emoji was in some ways more profound than that from punctuation mark to emoticon. Emoticons and emoji are both character forms but most emoticons, whether vertical or horizontal, essentially represent a face, while the content of emoji ranges widely — they are just tiny pictures. Further, emoticons are user-created images made of text, while emoji are strings of code that are transmitted by computers, then decoded into pre-defined images that users can manipulate. Emoticons have the immense combinatory possibility of characters and punctuation; emoji have the seemingly infinite range and diversity of pictures. And yet, the promise of possibility in both dead-ends against the inherent limitations of their forms: size, number, searchability. Further, to try to "humanize" communication by putting a "face" to it, or "universalize" communication with iconography cannot escape convention. While the emoticon and the emoji promise immediacy, specificity, and clarity of intention, they in effect display the variability and drift of all signs.

Emoji Drift

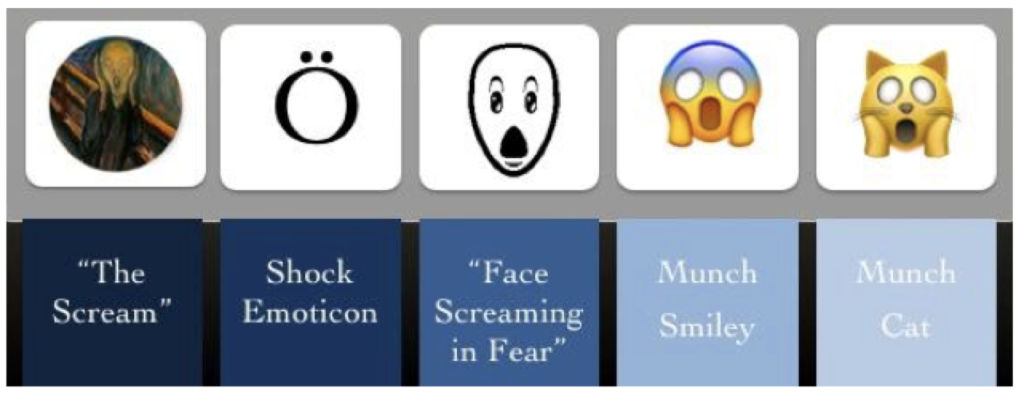

This perpetually shifting communicative ground is evident in the etymology and philology of certain emoji. Take the emoji 😱 ("Face Screaming in Fear"), defined this way on iEmoji.com:

Overwhelming fear, surprised probably pale afterwards, scare tactics.

iEmoji old name: About to scream, depressed.

Unicode note: Shocking (like Edvard Munch's "The Scream")

The multiplicity of its origins has led it to develop in unexpected directions:

"Face Screaming in Fear" riffs on the popular ASCII "shock" kaomoji. When it developed into an Apple emoji, this got blended with an allusion to Edvard Munch's painting, The Scream (1893). Its most recent version has subsumed the internet's ubiquitous obsession with cats. Pace Wikipedia, we are very far indeed from expressing one person's emotion or saving communicative time.

Another example is 😂, the "Face with Tears of Joy" emoji and the OED 2015 WOTY with which we began. Once upon a time, the emoticon XD was used to convey a face guffawing with its mouth open and its eyes closed — a visual analogue to the acronym LOL for "laughing out loud." The punctuation-based emoticon :'-) was used in a similar vein. These typographical depictions of intense laughter are not even equivalent to each other in expressive content or meaning, not to mention tone, nor language's drift toward ironic or contranymic uses. For instance, on some discussion forums, emoticons like XD, along with its phonetic transcription ecks dee, have become stigmatized as a form of sarcastic "shitposting."

Rather than resolving such ambivalence in meaning, however, we tend to ramify it through intensification. Here are three progressions toward "laughing very hard":

LOL ![]() LOLOL

LOLOL ![]() LULZ

LULZ

:) ![]() :D

:D ![]() XD

XD ![]() XDDD

XDDD

😃 ![]() 😄

😄 ![]() 😆

😆 ![]() 😂

😂 ![]() 😂😂😂

😂😂😂

It's possible that our tendency to repeat emoji — what I'll later dub "stacking" — is a vestige of language's limited capacity to signal intensification. (Note the bizarre semantic distortion of LOL into LOLOL — laugh out loud out loud — then into LULZ, ironically a homonym of "lulls.") The staggered repetition of XD into XDDD, which almost animates the letter D into a laughing mouth, is a little more logical but still weirdly multiplies only the mouth and not the eyes.

😂, affectively intense and concise, ought to have improved clarity while eliminating the need to repeat altogether. But the addition of tears and wrinkles to the emoji just introduced more semantic noise. According to a recent study, some interpret the OED's 2015 WOTY positively, while others interpret it negatively. Unlike its predecessor acronym and emoticons, users are in fact split on whether this emoji means "laughing so hard I'm crying," i.e. an intensification of laughter, or "crying through my laughter," i.e. a modulation that speaks more directly to an ambivalence at the core of the joke at hand.27 Despite recent attempts to render emoji more life-like, which aim to make emoji visually precise while still skirting the uncanny and grotesque effects of hyperrealism,28 we still love to repeat 😂. In other words, even as we move ever closer to a visual, lively face or a clear picture in the emoji, it maintains its slippery communicative character, what Derrida called iterability and dissemination.

Digital communication is famously opaque. Consider one medium where emoji are commonly deployed: instant messaging on platforms like GChat, iMessage, and Facebook Messenger. According to the New York Times, a 2014 study at Yeshiva University found that "when researchers crossed two unrelated instant-message conversations, as many as 42 percent of participants didn't notice."29 You might think emoji would improve things, as they put a face to the meaning and the moment of messaging. An NPR article observes:

Emojis were supposed to be the great equalizer: a language all its own capable of transcending borders and cultural differences. Not so fast, say a group of researchers who found that different people had vastly different interpretations of some popular emojis. The researchers published their findings for GroupLens, a research lab based out of the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. "I think some people thought that they could use [emojis] with little risk and what we found is that it actually is at high risk of miscommunication," one researcher said.30

This kind of miscommunication is ramified when we send text messages across platforms. Note, for example, how much angrier the "Thinking Face" emoji looks on a Samsung Galaxy![]() than on an iPhone

than on an iPhone![]() — an effect due to the darkened eyes, inverted right eyebrow, and frownier mouth.

— an effect due to the darkened eyes, inverted right eyebrow, and frownier mouth.

And as for transcending cultural differences, the last decade has seen a veritable Civil Rights Act's worth of debate about the identity politics of emoji. Is emoji yellow face?31 Why don't emoji include all the shades of skin and hair?32 Why are certain jobs depicted only as male?33 Even after Apple rolled out a range of options — blond and black; male, female, and androgynous; old and young; as well as a choose-your-own-ethnicity palette — new questions arose. Why a high-heel and no flat, and why a bikini rather than a one-piece?34 Why can't emoji get black hair right?35 What does it mean if you use an emoji shade darker than your own skin?36 What do we do about the adoption of emoji by political factions (the rose for socialists, the corncob for centrists, the OK hand for the alt-right)?37 These questions about emoji continue to index the anxiety about negotiating the individual and the collective that we saw in the -ism.

Many emoji have drifted toward unintended or multiple meanings. There is an entire subgenre of internet listicles and articles devoted to correcting reappropriations, often titled with some variation on "Emoji You're Using Wrong." The original Unicode name for 😤 is "Face With Look of Triumph" due to a Japanese cultural connotation. Because of how it was co-opted in Western affective circuits, the Apple name for this emoji is now "Huffing with Anger Face." 😁 is called "Grinning Face with Smiling Eyes" but it is only two eye-carets away from "Grimacing Face" 😬, which itself can be used to signify either distaste or awkwardness. 😵 was meant to signify dizziness but can convey shock or undergo metonymic slippage to signify orgasm — via the "O face" made during one. 😎, "Smiling Face with Sunglasses," alludes to being out in the sun but rather than "feeling hot," it metonymically signals "being cool," e.g. chillaxing on the beach. The sexual metaphorics of ![]() and 🍆 work by unintended resemblance. Some emoji feel like gestural punctuation: clapping

and 🍆 work by unintended resemblance. Some emoji feel like gestural punctuation: clapping ![]() hands

hands![]() between

between![]() emphatic

emphatic![]() words, or the "Speaking Head in Silhouette" emoji to exhort "broadcast widely!" "Person with Folded Hands" 🙏 has been read as a "High Five" and as "Prayer Hands," the latter of which takes on different cultural inflections: "I pray," "namaste," "inshallah," "praise be."

words, or the "Speaking Head in Silhouette" emoji to exhort "broadcast widely!" "Person with Folded Hands" 🙏 has been read as a "High Five" and as "Prayer Hands," the latter of which takes on different cultural inflections: "I pray," "namaste," "inshallah," "praise be."

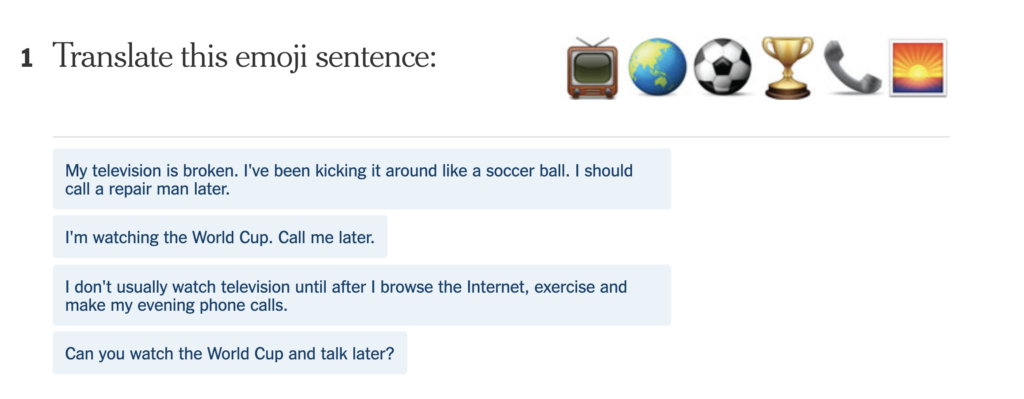

The diversity of interpretation, connotation, and affective intention in parsing emoji only grows when we combine emoji syntactically, as in this multiple-choice quiz in The New York Times:38

All of the above? This kind of quiz just seems to emphasize the fact that emoji are fundamentally unstable: they tend inevitably toward misinterpretation and misconstrual, malapropism and mondegreen.

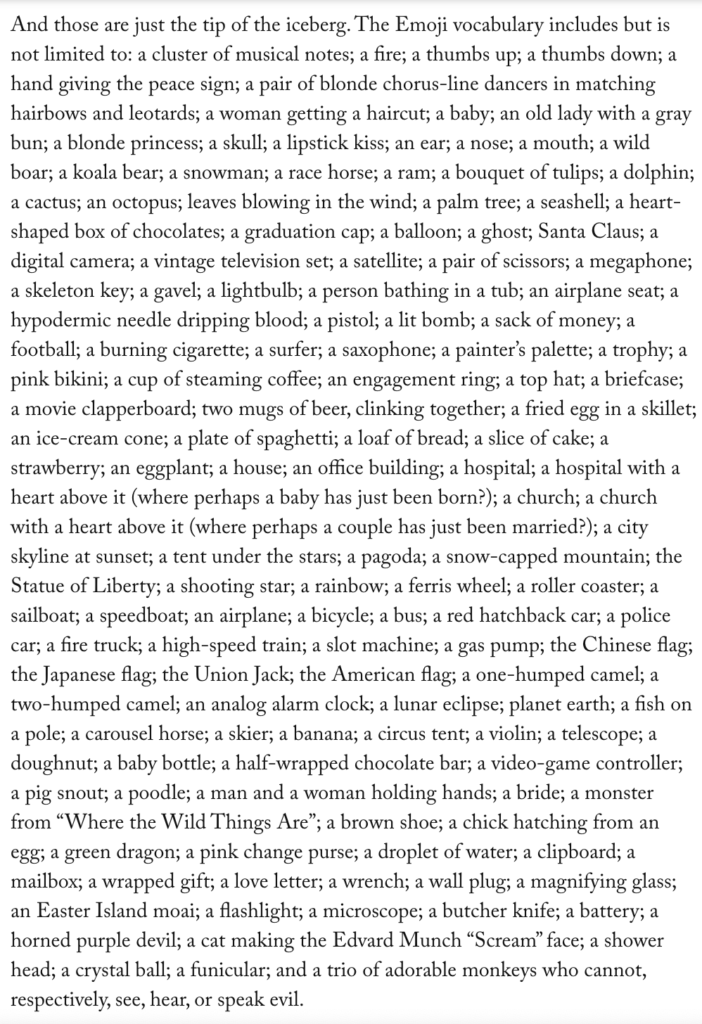

Rather than substituting for language, emoji end up producing copious textual translations, as in this ekphrasis of extant emoji in The New Yorker:39

The title of this article ("I ❤️ Emoji") of course begs the question — would you speak that as "I heart" or as "I love"? One article, "Do You Know What That Emoji Means?," both translates emoji into words and offers multiple definitions for them, occasionally insisting on one over the other as the "real" or "literal" meaning, as if that ever worked for human communication.40

The double desire to constrain emoji to syntactic, grammatical, and punctuational rules, and to delight in their refusal to obey them is evident in various versions of literary emoji. The Paris Review recently ran two sets of quizzes, presenting rebus-like lines that correspond opening stanzas of poems. Importantly, these are famous poems, so we are practicing recall as much as decoding in "reading" them.41 The prevalence of this emoji quiz format is telling: the effort to discipline emoji literacy acknowledges emoji's great variability, even as it characterizes improvisation and creativity as misuse.

Carina Finn and Stephanie Berger co-produce emoji poetry, or what the Poetry Foundation website calls "Emoji-Code Translations," which present a piece of free verse with a screenshot of an emoji-filled dialogue box. For instance:

Don't mess with me I have been congratulating myself all morning.

I walked along I walked alone I skipped and walked alone

I found a tangerine babydoll dress at Urban Outfitters

That flatters me better than the hand I hold now.42

The emoji and poetic lines use parallel punctuation (full stops) to stabilize how the signs correspond. This lets us see that there is no attempt to emoji-translate "all morning," "Urban Outfitters," or "flatters" in these lines. The "Flexed Biceps" emoji is a lovely hinge, tonally inflecting both "Woman Gesturing No" ("don't mess with me") and "Clapping Hands" ("congratulating myself"). The incidental orientation of some emoji to the left permits both reflexivity (the hands applaud the figured "self") and isolation (the figure walks "alone," away from the couple). The spareness of this emoji translation hints at an art — Poundian editing or poetic economy — that relies on the interlinear format for comparison.

In a recent article in this journal, Lisa Gitelman offers a wide-ranging meditation on another interlinear literary project, Emoji Dick (2010).43 This 736-page translation of Moby-Dick into emoji was devised, edited, and compiled by Fred Benenson; sponsored by a Kickstarter; "translated" by over 800 anonymous Amazon Mechanical Turk workers using the Project Gutenberg version of Melville's novel; and self-published through Lulu.com. Gitelman sees it as "a non-standard book object, a big joke, a complex assemblage shaped variously by global cultural flows — East to West and West to East — a conversation piece suited to the present time, and a provocation to consider the present and future of the literary." Her deft and fascinating comparisons between Emoji Dick and Melville's original novel run the gamut of critical approaches: translation theory; genetic, production, and book history; global context and circulation; literary genres, including world literature; bibliographic classification; medium specificity; digital and print culture; and reception history, including that of these texts' afterlives.

Notably, Gitelman does little by way of close reading this "pleasurable, perverse, and provocative object" because, as she notes, "if — as my students say — half the fun of Emoji Dick is saying it, then the other half is not reading it." Gitelman connects this to other forms of "not reading": the canonical unreadability of Moby-Dick; distant reading; online browsing (hyperreading); and joke texts, art books, and conceptual works that both resist reading and point to its futility. Gitelman ascribes some of this unreadability to Emoji Dick's sheer size and the patchwork conditions of its production. But in Gitelman's analysis, there also lurks an underlying tension about whether an emoji translation is "real writing" — an undertheorized term, which slides in her essay between the "linguistic," the "verbal," "syntactic utility," the "grammatical," and the "literary."44

On one hand, Gitelman claims, emoji "most assuredly belong" not to books or literature but to "diminutive semantic habitats" like texts and tweets. Emoji Dick cannot be a translation because "emoji are pictorial not linguistic. Pictographs are not real writing. They lack the flexibility and range of written language." They rarely "have syntactic utility," and afford only "some interesting observations about the differences between ... literary and non-literary discourse." Given their nominal bent, "how can emoji work practically or consistently as adverbs, pronouns, articles, or adjectives? How can they convey ... grammatical relations?" In sum, "emoji beg the question of universal language without being language at all."45

On the other hand, Gitelman concedes, emoji "work like language in several respects, even if what they communicate remains pretty fuzzy, or warm and fuzzy." And if "emoji aren't true writing ... they are handled as if they were." Verging on "oral forms of communication," she continues:

emoji greedily inhabit the tonal register, less as signs with semantic value and more as phatic expressions, communicating the in-commonness of communication. Emoji in this sense hold the channel open as signifiers of "affect, emotion, or sociality," marking the existence of senders and recipients as subjects within a shared exchange, enabling the expression of affective states amid otherwise linguistic communications.

Emoji indeed ride this line between the linguistic and what I'd call the para-linguistic rather than the non-linguistic. But Gitelman's essay suggests an anxiety about usurpation that also rears its head in a definition of emoji she quotes more than once: "a small invasive cartoon army of faces and vehicles and flags and food and symbols trying to topple the millennia-long reign of words."46 For Gitelman, if Bennison's translation is unreadable, the blame falls primarily on the emoji side: "Emoji Dick sidetracks linguistic communication in general and literariness in particular by invoking pictograms as not writing that cannot be read."

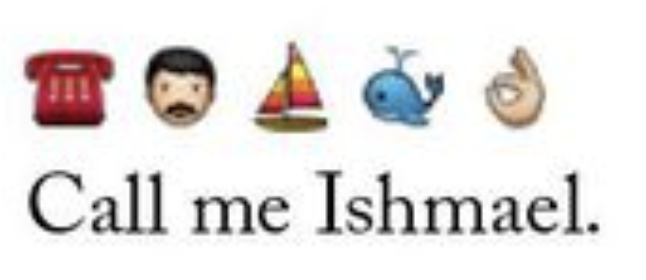

Like much of the emoji literature I've found, including the quizzes and poems above, Emoji Dick does seem to defeat the purpose by including the original underneath the emoji translation:47

Note that several icons (a ship and a whale, an OK sign) are added to suggest context and tone for Melville's famous first line. Although this interlinear format seems to showcase the insufficiency of emoji, it evinces, as Gitelman notes, Walter Benjamin's ideal: "All great texts contain their potential translations between the lines."

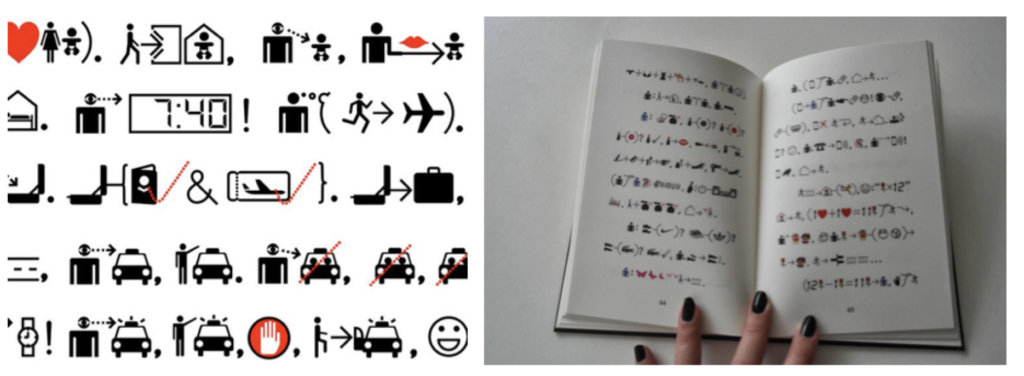

You might think emoji would "translate" better to or from character-based languages, given some of their shared pictographic and geographic origins. But I share Gitelman's reservations about the work of Chinese writer and conceptual artist Xu Bing, who has written a novel in emoji called Book from the Ground.48 "Twenty years ago," he writes, "I made Book from the Sky, a book of illegible Chinese characters that no one could read. Now I have created Book from the Ground, a book that anyone can read." MIT Press concurs with this claim to transparency: "Xu Bing's narrative, using an exclusively visual language, could be published anywhere, without translation or explication; anyone with experience in contemporary life ... can understand it." Well, you tell me:

There's a kind of puzzle pleasure to this sort of thing, but to me, the pages of Book from the Ground look daunting — exhausting before I even begin — despite Bing's insertion of arrows to help guide the eye, supplemental marks that question emoji's supposed legibility or immediacy. Gitelman says the rewards do not justify the effort: "there is utterly nothing literary about it ... 'Readers' may decode the story and enjoy doing so, but they are hardly reading. According to another observer, they are doing 'a transformative mental exercise that lies somewhere between reading and seeing.'"49

But what if this "transformative mental exercise" were analyzed for what it affords because it is both reading and seeing, rather than disregarded because it is neither? What if the failure of Benenson's and Bing's projects is not a matter of emoji's lack but rather a matter of trying to constrain this new sign to pre-existing forms: the codex, the novel, the category of "the literary"? In other words, what would it look like if we were to imagine entirely new genres, formats, or habitats for emoji rather than simply dismissing emoji as "not writing"? For example, in studying these extant examples, I began to wonder if all emoji literature is fundamentally interlinear. And if that trope is recognized and categorized by literary critics and practitioners, might it eventually become a mark of art: deployed or distorted at will in emoji literature, like the footnote or the preface in the novel?

I'm drawn to the idea that emoji are contemporary, ambivalent, hybrid signs that afford novel, if not entirely novelistic, uses. They are not purely linguistic, no, but nor are they purely pictographic. Some include words, some are symbols, some act as punctuation, others are more phatic, et cetera — and many lack the stability of pictographs. They are often redirected toward surprising meanings, subject to what Ferdinand de Saussure called difference — the reliance of signification on the differentiation of written letters, sounds, and semantic units. And they seem rife with what Jacques Derrida called différance, punning on to differ/to defer, and what Jacques Lacan called the glissement of signifiers and signifieds: a drift, slippage, or sliding of meaning over time.

In his Course in General Linguistics (1916), Saussure famously uses pictures of a horse and a tree in order to depict his concept of "sound-image," which he terms the signified; images seem to allow him to express his theory of language without muddling it with more language. But, of course, Saussure made specific choices for his "universal" tree: Which tree is iconic enough to signify the broader category "tree"? Which illustration? Which species? From which part of the world?50 And, as Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari would ask in A Thousand Plateaus, why (yet another) tree? ("We're tired of trees," they write, like bored botanists.)51 My current iPhone has a cactus, a palm tree, an oak, a pine tree, a Christmas tree, and several varieties of leaves. These emoji, both singular and plural, could each signify "tree," their specific species, or any number of associations ("desert," "holidays") depending on the context.

In "The Agency of the Letter in the Unconscious" (1966), Lacan reproduces Saussure's tree only to replace it with the image of two bathroom doors, labeled Ladies and Gentlemen respectively, arguing that Saussure's illustration is "an error" because it portrays the sign as representation without accounting for its "law-giving" function when it comes to the body.52 The emoji debates about gender and race described above epitomize Lacan's claim for signs' material effects, which also prefigures the irony of Xu Bing's use of the gentleman icon from bathroom doors for the unmarked "everyman" in his emoji novel. Lacan also offers in this essay a proliferative riff, what he calls a "signifying chain," on the various connotations of Saussure's tree — "the robur and the plane tree," "strength and majesty," "the shadow of the cross," "the tree of life," et cetera — predicting the abundance of meanings attributable to even the seemingly most iconic emoji.53

Derrida reproduces an image of his own signature in "Signature Event Context" (1972) to enact his argument about the iterability of even the ostensibly authentic, intentional, handwritten mark.54 Our "signature emoji" (mine is the Sideways Monkey or the Hatching Chicken, depending on my audience) are similarly reproducible — they are "ours" only in the sense of having a favorite product — and individualized. Emoji thus highlight what all three of these theorists recognized: that even the images with which they each diagrammed their concepts are as shifty as words.

In her 1993 essay, "Virtual Bodies and Flickering Signifiers," N. Katherine Hayles offers a set of distinctions between print and digital technology that help us see what kind of a sign emoji might be. Hayles suggests that the dialectic of absence and presence found in the discourse and production of print (black ink on a white page), shifts toward a dialectic of pattern and randomness in the digital screen: "Carrying the instabilities implicit in Lacanian floating signifiers one step further, information technologies create what I will call flickering signifiers, characterized by their tendency toward unexpected metamorphoses, attenuations, and dispersions." Hayles emphasizes that "flickering signifiers" entangle embodiment: "interacting with electronic images rather than a materially resistant text, I absorb through my fingers as well as my mind a model of signification in which no simple one-to-one correspondence exists between signifier and signified."55

Some neuroscience studies suggest that the human brain recognizes emoji as nonverbal communication — more like tone, gestures, and expressions than words. Other research shows that when we look at emoji, the same parts of our brain that respond to human faces light up; we unconsciously imitate and respond positively to them — we treat even a "sad face" emoji as a sign of "playfulness."56 Hayles' work shows us that this haptic and affective bent to emoji does not make them any less signs. Emoji might initially register as nonverbal but, in use, they fall rapidly into the patterns of interpretation and improvisation we associate with words.

Gitelman is intrigued by how "eponymy short-circuits" on the cover of Emoji Dick, which replaces the noun in Melville's subtitle "; or, The Whale" with the "Spouting Whale" emoji, 🐳, which is neither an accurate image (it isn't white) nor a name, but a dick pun.57 Rosana Bruno's cartoon "Emoji Dickinson" inspires Gitelman to imagine a future Emoji Dickens.58 I can even picture a title page that simply said: 🍆; or, 🐳. (Durex has already taken up the eggplant emoji trope to sell condoms.)59 Emoji — like concrete poems, pop art, and clichés — are signs; they're just "flickering" signs that we play with rather than read, exactly.

A Stack or A Stagger of Faces

Let's pursue the idea that emoji are material signs for affective exchange rather than just semantic vehicles, in the name of accounting for them rather than denigrating them. We rarely arrange emoji like words in a sentence nor do we just fashion them into rebuses. In fact, in practice, we often stack them, pile them up on the screen. Even with the advent of supersizing (the "blooming" effect we get when we use 1-3 emoji on an iPhone), I'm sure we all have examples like this lurking on our phones:

This is the very first text message my then six-year-old nephew ever sent to me, before the predictive emoji feature. First we see an effort to use standard language (okay, adorable language), possibly with an effort to sign the sentiment with a face (though he definitely isn't blonde). But then, almost immediately ... the stacking. Specificity (an emoji that he thinks looks like his face?) gives way to a cluster of emoji that might all signify him (from the face to the ghost to the psychic kid). I'd say that this is like a puppy just pounding piano keys, were it not for his subsequent effort to use the emoji in a sentence ("I am doing ⚽," followed by ... more piling). I confess, I do not know exactly what these messages meant. But the impulse toward repetition as an expression of affect comes through loud and clear.

The emoji in every platform (Apple, Google, Microsoft) are similar — it's like they're in the same family, or as Gitelman puts it the same "font" — but they also offer a range of expression and juxtaposition. It's telling that when Apple gave us the option to "color" emoji racially (a laudable but Sisyphean task60) they didn't apply this modularity to the most common ones: the various smiley faces, the ur-moji, so to speak. Honestly, I don't think we would want them to — for one, it would make the "yellow face" lurking behind the standard emoji face more legible and more troubling to us.61 And I think we in fact enjoy the repetitiveness of emoji, laid out grid-like on our phones, as browsable as the products on the shelf of a store or the screen of a shopping search engine.

The emoji's ramified redundancy — its repeatability, recognizability, and reduplication — affords this stacking effect, the piling up of emoji in a tumbling grid down the screen. We've seen that the emoji's ontological oscillations (between the word and the image, the specific and the general) yield semantic instability. This uncertainty in turn manifests in those infamous symptoms of stalled compulsivity: repetition and proliferation. That is, while emoji don't in fact afford direct or transparent communication between users, they do spur a powerful desire to fret over and fondle that possibility. Our desire for emoji to signify comes up against their failure to do so, affording a compulsive touching of the screen or keyboard, a fetishistic fingertapping pleasure more clitoral than onanistic.

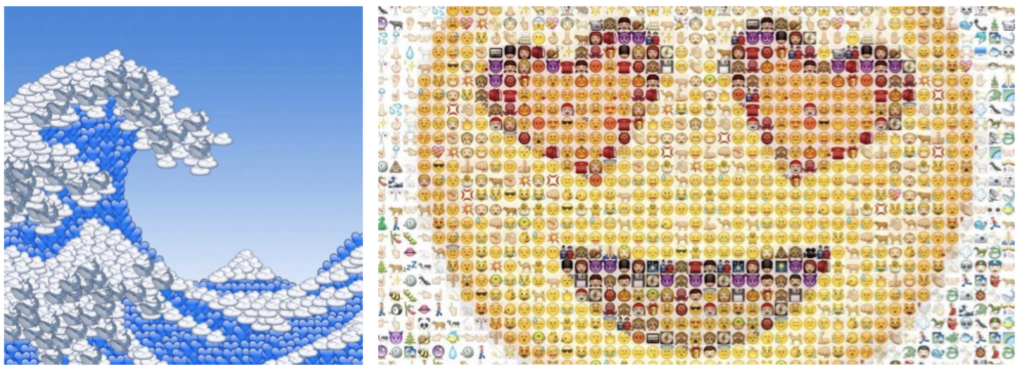

The near-universal dislike for The Emoji Movie (7% on Rotten Tomatoes) and the outcry against the greater "realism" of emoji both suggest that we in fact perversely prefer our emoji inadequate, catachrestic, ambiguous, opaque. Emoji ontology thwarts direct comprehension but makes them materially available for a particular kind of artistic play. When you Google "emoji art," a lot of kitschy mosaic-like works come up:62

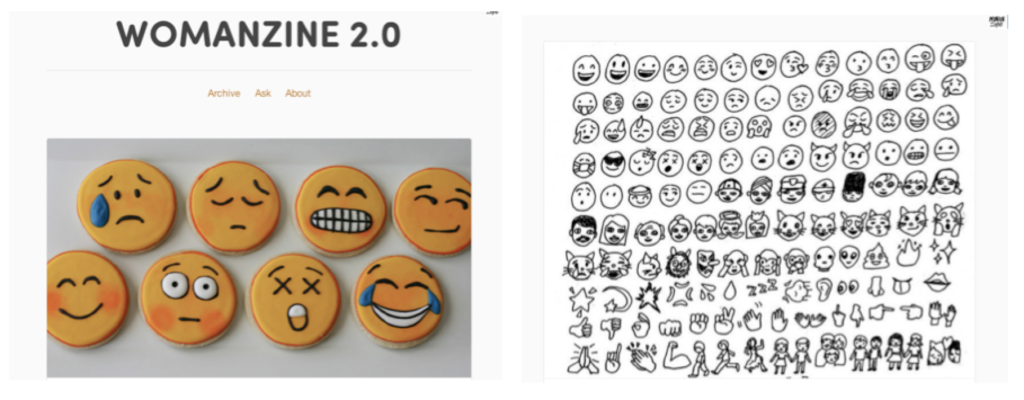

These works suggest that the emoji affords synecdochic, pixelated effects, and spatial recombination. But more interesting to me are recreations like these literal emoji "cookies" or backformations like these messy drawings of emoji (an inverse of The New Yorker's ekphrasis):63

Here, the generality of emoji — emoji-ness — supersedes what each emoji means. It's akin to our tendency to compile, rather than gloss, clichés in anthologies or dictionaries. Emoji art does not aestheticize in modernist fashion — it doesn't render the emoji "beautiful" or "sublime," nor "make it new." Rather, defamiliarization of the emoji works through context, framing, medial play, puns, repetition, or augmentation. In this sense, it's closer to Pop Art. The best pieces of emoji art I've seen play with the stacked effect we saw in my nephew's texts — the set-like, grid-like format that coordinates singular and plural — but also with a staggered effect: a shifty or staccato temporality that has its visual analogue in skew, imbricate (overlapping), and flickering forms.

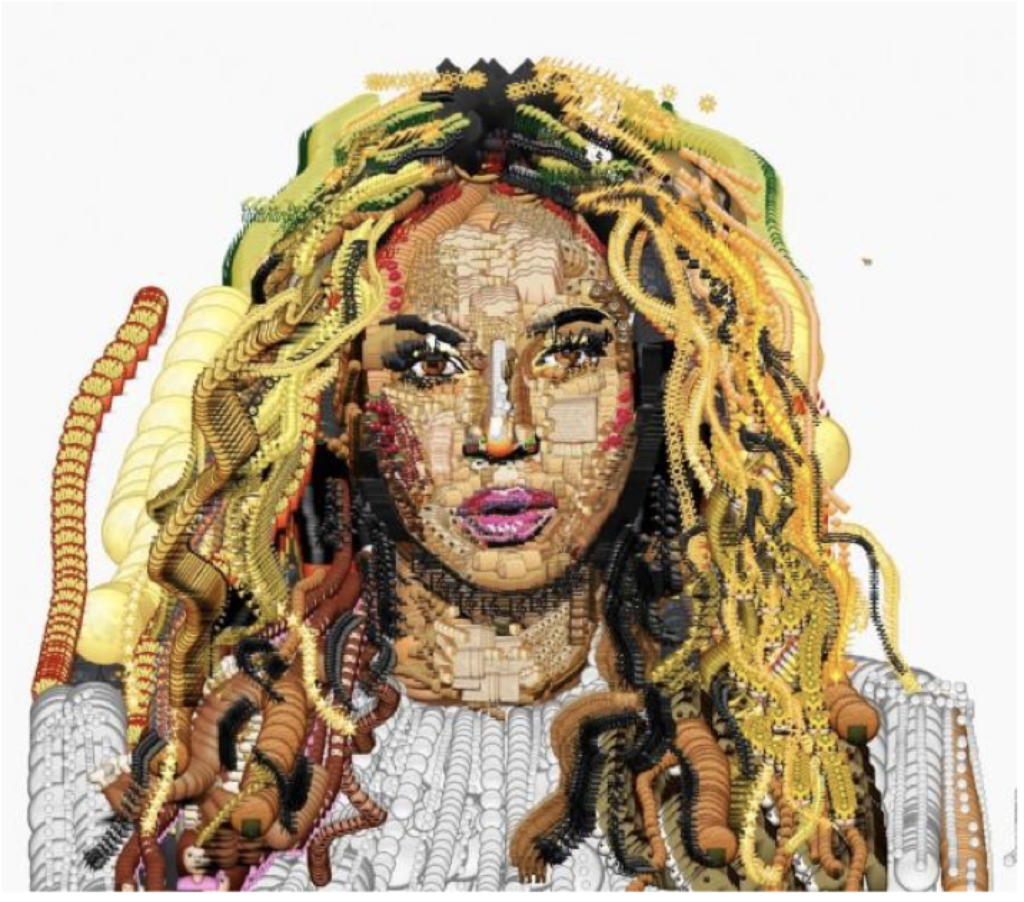

The artist Yung Jake has been using the emoji paintbrush tool, emoji.ink, to make distinctively twenty-first century portraiture.64 As Vice magazine puts it, Jake uses emoji ink "to transform music notes into Kim Kardashian's hair, envelopes into Wiz Khalifa's teeth, and 'index pointing up' emoji into the Seinfeld creator's chin."65 In his choice of subject matter and medium, Yung Jake's work is reminiscent of Andy Warhol's renditions of celebrities, Roy Lichtenstein's paintings of comics, and Chuck Close's late dilated-pointillist portraits.66 Yung Jake tweaks the latent queerness and culture of consumption in hip hop, incorporating french fries, cookies, cherries, and kiss marks into a portrait of Beyoncé:

The stacking of emoji achieves its ironic apogee here, as the form's tendency toward grids and repetition is both alluded to and distorted via an overlapping effect like roof tiles or playing cards.

This imbricate aesthetic corresponds to our experience of looking at/reading the emoji in these paintings, too: the way we shuffle between semantic and visual metaphors as we zoom in. Is Beyoncé as sweet as cookies and cherries, as addictive as french fries, or are these simply the best emoji to capture the shades of her physiognomy? Is Jake making a celebration or a critique or a joke of our sexualized and commoditized desire to consume her (as per the rumor that actress Sanaa Lathan bit Beyoncé's chin at a party)?67 Is Beyoncé made of kisses or does she compel our kisses and would this many literal kisses gradually blur her features like the touch of a million lips to an icon? Once again, meaning and intent become skittish as we equivocate over the extent to which the artwork is immersed in or indulging in the ostensible object of its critique. This form of irony has long been around (Warhol again seems the resonant predecessor) but feels amped up in our era: the combined earnestness and irony of the hipster, the guilty pleasure of the consumer.

One of the most iconic/ironic use of emoji in pop culture is an "emoji translation" of Beyoncé's 2013 song, "Drunk in Love," which you can now see only via a video of a video due to copyright infringement. If the Paris Review quizzes cited above rely on our prior knowledge of famous poems, this video relies on our familiarity with pop music. But even those who somehow missed Beyoncé's ubiquitous song can follow along because, in a kind of intermedial interlinearity, the music plays over the emoji, which, perfectly timed, flash rapidly or rhythmically on and around the screen à la VH1's Pop-Up Video. Within the first few seconds, we flit through emoji to set the mood (![]() ,

, ![]() , 🚹, 🚺, 🚻, 🚼 —Lacan's bathroom signs again!); we learn which emoji will signal "I" (

, 🚹, 🚺, 🚻, 🚼 —Lacan's bathroom signs again!); we learn which emoji will signal "I" ( ![]() ), "you" (a British guard emoji

), "you" (a British guard emoji ![]() = Jay Z in a wool hat), and the endearment "baby" (

= Jay Z in a wool hat), and the endearment "baby" (![]() ); we see different emoji to signify "drunk" (🍺, 🍸) and a stand-in (🚬) for "cigars," which doesn't yet have an emoji; and we get a glorious metonymic slippage in the translation of "ice": a snowman (⛄) who vanishes and reappears bracketed by two jewelry emoji (

); we see different emoji to signify "drunk" (🍺, 🍸) and a stand-in (🚬) for "cigars," which doesn't yet have an emoji; and we get a glorious metonymic slippage in the translation of "ice": a snowman (⛄) who vanishes and reappears bracketed by two jewelry emoji (![]() ,

,![]() ) that gesture to the hip-hop slang for diamonds.

) that gesture to the hip-hop slang for diamonds.

For a while, Beyoncé's website sold t-shirts based on this video, which epitomize the ineluctable gap between emoji intention and emoji expression:

The lefthand t-shirt refers to a near-insane slippage in the song between "riding" a surfboard and "riding" a sex partner — this is not a metaphor (no one rides a surfboard that way) but a metonym derived from the idea of riding something that is proximate to "surfboard abs." The righthand t-shirt is more sexually explicit (though the word doesn't appear in the lyrics), even if only certain interpretive communities will recognize the cherry emoji as a symbol for testicles.

The levels of mediation between these supposed "translations" not only, again, belie the transparency of the emoji, but also suggest a proliferative punning (as when Moby-Dick; or, The Whale becomes Emoji Dick; or, 🐳 becomes 🍆; or, 🐳). With emoji, we might catch a meaning a second late, or move through two or three meanings to get there, as the "Drunk in Love" video does when it flicks rapidly through several emoji (🐻🐹 🐴🐰🐯 🐭) while Beyoncé drones "feeling like an animal." This is what I mean by the staggered phenomenology of emoji, a stuttering or staccato or double-take or flickering effect that suits the halting and, again, masturbatory rhythm of new online media forms like the GIF. Rather than developing meaning in the linear fashion of words, qualifying it in the fashion of punctuation, or enhancing it by bestowing it with emotional intention, stacked and staggered emoji instead produce brief bursts of affective intensity and interpretive pleasure. These "unexpected metamorphoses, attenuations, and dispersions" of Hayles's flickering signifiers derive precisely from the unstable play of meaning within emoji — both within an individual emoji (as when ![]() denotes jewel, connotes wealth, signifies ice, and alludes to hip-hop) and within emoji as a set (as in the joke of the shift from ⛄ to

denotes jewel, connotes wealth, signifies ice, and alludes to hip-hop) and within emoji as a set (as in the joke of the shift from ⛄ to ![]() ⛄

⛄ ![]() ).

).

The Politics of Emoji

This aesthetic and experiential oscillation within the single polyvalent emoji, and between several emoji within a set, returns us to the question of the individual and the collective. I want to turn now to consider how emoji bears on the questions about contemporary social relations raised by Merriam-Webster's 2015 WOTY: all those -isms. In her essay, "Visceral Abstractions," Sianne Ngai argues that the birth of the smiley face in "the golden age of capitalism" was no accident:

[T]he cheerful visage we find stamped not just on food but on virtually every type of artifact of the capitalist economy, from Band-Aids to diapers to text messages, is obviously not a representation of a specific, unrepeatable individual, nor even the idea of one. The smiley face rather expresses the face of no one in particular, or the averaged-out, dedifferentiated face of a generic anyone. It calls up an idea of being stripped of all determinate qualities and reduced to its simplest form through an implicit act of "social" equalization, or the relating of each and every individual face to the totality of all faces ... Whether as the bloodstained smiley of Allan Moore's Watchmen or the relentlessly affirmative "roll-back" smiley of Walmart, however, the smiley always confronts us with an image of an eerily abstracted being. Is the disturbing effect of this icon's averaged-out appearance something we should chalk up to a long-standing American phobia about the loss of individual distinction to social homogenization? Or could it be registering something else?68

The capitalist smiley, then, "is not just an image of abstract personhood but also an uncanny personification of the collectively achieved abstractions of the capitalist economy: abstract labor, value, capital."69 For Ngai, this is what Marx, speaking of labor, describes as the "connection of the individual with all, but at the same time also the independence of this connection from the individual."70

Ngai goes on to cite the passage in Capital where Marx analogizes the general equivalent within a value system (the money form) to the animal kingdom: "It is as if, in addition to lions, tigers, hares, and all other really existing animals which together constitute the various families, species, subspecies, etc., of the animal kingdom, the animal would also exist, the individual incarnation of the entire animal kingdom."71 (The absence of this general animal is why Beyoncé's "animal" has to be translated as a flickering series of exempla.) But apart from the conceptual puzzle that it poses, Ngai confesses, this passage also gives her "the willies." The capitalist smiley, too, promotes "visceral feelings" within her: it is an "uncanny personification" with an "unflinching gaze"; it is "palpably unsettling" and "eerily abstracted" due to its "averaged out appearance."72

Why don't emoji produce these Gothic effects of shiver and disgust? Are they too affectively intense, too id-like — more Animal from The Muppets than Marx's the animal? Or are they too abstract? Even the blandest emoji seem likelier to provoke boredom than discomfort — as per people's responses to The Emoji Movie or to this building in the Dutch City of Amersfoort:

Architect Changiz Tehrani explains: "In classical architecture they used heads of the king or whatever, and they put that on the façade. So we were thinking, what can we use as an ornament so when you look at this building in 10 or 20 years you can say 'hey this is from that year!'"73 Yet these are obviously not functional gutters, and while gargoyles are famously all different from one another, each emoji stares the same way down at us, emitting neither rainwater nor meaning nor feeling. If, as Tehrani says, "only faces were chosen as they were the most expressive and recognizable emoji," what do they express beyond the notion of expression? What does each sign signify beyond the idea of a new kind of signification — a sign of the times, so to speak, to serve as a future mnemonic?

This architectural version of the WOTY — a BOTY? — is a contemporary version of the postmodern buildings that, per Jameson, reflect the cultural logic of late capital.74 This literal monument to emoji not only feels like commissioned graffiti — that classic tell of urban gentrification — but it also spatializes emoji in an unfamiliar way. We are used to seeing emoji closer together, more of them in a row, or in a staggered, Tetris-like stack. These ones are isolated, too far apart to work semantically or syntactically or juxtapositionally. Staring out blankly at us, they seem a parody of Althusserian interpellation, a faces-to-faces encounter, so to speak, that only serves to forge the (mis)recognition of ideology — "the 'obviousness' that you and I are subjects."75

The emoji wears capitalism but with a different skin — to use the term for the way companies render each Unicode with their own personalized, and copyrighted, design.76 If, per Ngai, the smiley is the apotheosis of late capitalism's conformity, abstraction, and commodity production, the emoji highlights the particularly neoliberal celebration of customized choice and variety in the contemporary moment. Emoji come with most platforms, and there have been several spin-off products, like kaomoji and topic-specific emoji keyboards and apps. But even the popular Apple platform continues to proliferate new emoji, from about 90 to 2,600 in the last decade, due to the petition-based introduction of new ones via software update. Apple has tried to limit our ensuing anxiety about an endless profusion of emoji with its "frequently used" emoji feature and a newer "predictive emoji" feature, which highlights words in your message and suggests emoji with which to replace them. This assumes, of course, that every word potentially has an emoji substitute, though the phone can't (yet) read your mind for what you wish to express.

Hence what a friend of mine and I have dubbed the premoji. A portmanteau of premonition + emoji, a premoji is the feeling you get when you're hunting on your phone for an emoji that doesn't yet exist. You want to use it; it should be there; you feel almost sure you've seen it before; but you can't find it. It's the digital version — in both senses of the word — of something being on the tip of your tongue. If nineteenth-century free market capitalism is embodied in that phantom limb, Adam Smith's invisible hand of the market, then perhaps our contemporary version of capitalism — with its pretense to total access, individuation, and customization — is embodied in the premoji, the promise of everything at the tip of your finger.

The tension between individuality and abstraction that Ngai sees in the capitalist smiley face ("the relating of each and every individual face to the totality of all faces") is present in the set problem of the emoji as well. While the ur-moji have stayed the same, we are still in the midst of debate about what an "unmarked emoji" ought to be, as suggested by constant calls (and failures) to diversify emoji along the lines of race, gender, sexuality, and class. This debate is itself a sign of neoliberalism, which is deeply entwined with the idea of choice and with identity politics.77 But for now, this tension within the emoji is live — an active, flickering oscillation rather than a merging into uniformity. Ngai argues that capitalist smiley faces "confront us with ... the radically alienated status of sociality itself under conditions of generalized commodity production,"78. Emoji would seem to imply a sociality even more fragmented — because more various and proliferative and, worst of all, ubiquitous in digital communication.

The Trump Era has heightened an anxiety, if not an outright hysteria, in the U.S. about the internet, particularly social media's disintegrative and destructive effects on society — on our sense of reality, our personal relations, our democracy, and so on. But these laudable efforts to examine the political effects of the social media revolution often neglect the ways "being on here" (as Twitter users put it) can offer safety and solidarity for marginalized people, particularly those in the black and/or queer community. A recent Pew Research Center study suggests that "whites are more likely than the rest of the U.S. population to think social media platforms have a negative impact" while 80% of black Americans "value the platforms for magnifying issues that aren't usually discussed," like Black Lives Matter.79 I have also seen black, queer, trans, and neurodivergent users tweet about the anonymity of social media not as isolating, enervating, or dangerous, but as a respite — a safe, positive way to connect to others and forge political solidarity. Digital communication does not just cause alienation. It also affords more opportunities to recognize intersectionality, make contact with unlikely allies, and stumble on the cracks in ideology where change might erupt.

The staggered and stacked effects I describe above suggest to me that emoji have the potential to warp the temporalities and logics of the free market from within, diverting us from the causal trajectories, ordered accumulation, and supposedly spontaneous, direct, and transparent affects of capital. To be clear, emoji is a commodity that reflects a neoliberal form of late capitalism. It relies on the purchase of an expensive item (a smart phone) that renders invisible the often horrific labor practices that subtend its production. The emoji as we use it does not counter capitalism's imperative to produce and customize; rather, it draws our attention to its absurdity.

This may just seem like that contemporary irony I noted as a possibility in Yung Jake's art — bad faith delectation in the hieroglyphs of commodity fetishism. And it may be just a matter of time before the emoji goes the way of the smiley — taking up its banal place in the land of Forrest Gump blockbusters and corny bumper stickers. But I find it interesting that when corporations or advertising or movies try to swallow emoji and spit them back at us, we tend to reject the effort or find it unappealing. We have been offered, and largely declined, for example, Ebroji and Homojis.80 While giant Silicon Valley companies continue to diversify and monetize our portfolio of emoji options, we still harp on our favorites, repeat them to opacity, render them illegible to outsiders, and slip them into new contexts.

We even use them to duck surveillance. In 2015, a seventeen-year-old kid from Brooklyn named Osiris Aristy was arrested and charged with making terrorist threats against police officers on Facebook. 81 The threat looked something like this: ![]() 82 Without getting into the ins and outs of the trial, I don't think it's farfetched to hypothesize that the charges were eventually dropped because of the ambiguity of emoji. The oscillation between specificity ("I'm going to kill that cop") and generality ("Fuck the police") is here a saving grace for Aristy, as is the unsystematic repetition of the emoji, which could have been intended as an intensifier or as a commentary on American gun culture. This particular juxtaposition of icons could be, or could describe, a protest against police brutality. It could even comprise the opening line of a poem, like this one from a Paris Review quiz:

82 Without getting into the ins and outs of the trial, I don't think it's farfetched to hypothesize that the charges were eventually dropped because of the ambiguity of emoji. The oscillation between specificity ("I'm going to kill that cop") and generality ("Fuck the police") is here a saving grace for Aristy, as is the unsystematic repetition of the emoji, which could have been intended as an intensifier or as a commentary on American gun culture. This particular juxtaposition of icons could be, or could describe, a protest against police brutality. It could even comprise the opening line of a poem, like this one from a Paris Review quiz: ![]() (According to the magazine, this is Walt Whitman's "O Captain! My Captain!")

(According to the magazine, this is Walt Whitman's "O Captain! My Captain!")

I have come across less contentious examples where emoji take an unexpected, thrilling swerve toward nontraditional, politically resonant uses. Beyond the banal sexualization of various fruit emoji (an old and storied way to duck censorship), black/queer communities have creatively adopted and adapted emoji:![]() is "peep this" or "side eye";

is "peep this" or "side eye"; ![]() suggests the commenter is unfazed; 🐐 = goat = G.O.A.T. = Greatest Of All Time; ☕ can imply sipping your tea, again unfazed, or "that's the tea," i.e. the gossip (exchanged over tea since Jane Austen's days). Before Black Panther was granted its own emoji, Black Twitter appropriated the "Woman Gesturing No" emoji (

suggests the commenter is unfazed; 🐐 = goat = G.O.A.T. = Greatest Of All Time; ☕ can imply sipping your tea, again unfazed, or "that's the tea," i.e. the gossip (exchanged over tea since Jane Austen's days). Before Black Panther was granted its own emoji, Black Twitter appropriated the "Woman Gesturing No" emoji (![]() ) to imitate the Wakanda salute.83 A Twitter feed called @BlckPeopleEmoji appeared in 2013, with this emoji for an avatar: 🌚. The 500 or so tweets and retweets from this account essentially existed to point out that, at the time, the only emoji we could use for a black person was the "New Moon Face" emoji. Along the way, came a riff:

) to imitate the Wakanda salute.83 A Twitter feed called @BlckPeopleEmoji appeared in 2013, with this emoji for an avatar: 🌚. The 500 or so tweets and retweets from this account essentially existed to point out that, at the time, the only emoji we could use for a black person was the "New Moon Face" emoji. Along the way, came a riff:![]() , which while obviously ineffective as a sign, hilariously parodies America's obsession with "the color line."

, which while obviously ineffective as a sign, hilariously parodies America's obsession with "the color line."

Signifyin' with tiny cartoons might seem a low bar to set for political change. But the ways marginalized communities adapt emoji — how they turned the short-lived Vine (#RIPVine) into an artform, and for that matter, how they regularly, reliably infuse popular culture with catchy words and memes — enhance our capacity for expressivity, offering novel terms for what Iris Murdoch called a "new vocabulary of attention" and a "new vocabulary of experience."84

My favorite near-opaque emoji pun to date came from a Twitter user with the handle Yvangelista ("P.S.," her bio notes, "I am sis, not cis."):

Put aside the context — a cartoon that Yvangelista is calling out for its ableism — and attend to the phrase "Whew 🇨🇱." The Chilean flag ![]() Chile

Chile ![]() chile (an AAVE transcription of "child"): "Whew chile." Yvangelista's emoji use doesn't clarify the sense or add feeling, emphasis, inflection, or speed to the expression of her sentiment. If anything, it makes the reader pause, puzzled, then grin with delight. It is a beautiful piece of communication — sonically and visually and poetically — even if it is a semantic non sequitur (neither the Chilean flag nor Chile nor the political situation in Chile are relevant to the tweet). It reminds me of the pictographs in novels (Shandy's plot graph; Faulkner's coffin; Pynchon's post horn) and Nabokov's cross-linguistic puns. It is a perfect example of emoji's coy resistance: to logic, meaning, corporatization, even the gravitas of the nation-state.

chile (an AAVE transcription of "child"): "Whew chile." Yvangelista's emoji use doesn't clarify the sense or add feeling, emphasis, inflection, or speed to the expression of her sentiment. If anything, it makes the reader pause, puzzled, then grin with delight. It is a beautiful piece of communication — sonically and visually and poetically — even if it is a semantic non sequitur (neither the Chilean flag nor Chile nor the political situation in Chile are relevant to the tweet). It reminds me of the pictographs in novels (Shandy's plot graph; Faulkner's coffin; Pynchon's post horn) and Nabokov's cross-linguistic puns. It is a perfect example of emoji's coy resistance: to logic, meaning, corporatization, even the gravitas of the nation-state.

This is not to make a grandiose claim for the emoji as tool for the revolution, but to note that, as always, marginalized communities have taken what's been forced on them, and used it for entirely unexpected and occasionally countercultural purposes. Emoji, like capitalist smiley faces, are symptomatic of neoliberalism and the global market, but they also afford ways for us to pervert those systems from within: by stacking emoji up until they overflow into a cascading avalanche of absurdity, or using them to create private codes and interpretive communities, or activating them for political action (#BLM and #MeToo both have their own emoji), or deploying them in ways that jam the circuits of transparent transmission and forge unlikely forms of solidarity between individuals pushed to the margins of society. To the undecidable oscillations of emoji's ambivalent ontology (face/sign, specific/generic, individual/collective, earnest/ironic) we can add one more: pleasurable/political.

C. Namwali Serpell is a Zambian writer who teaches at the University of California, Berkeley. Her first book of literary criticism, Seven Modes of Uncertainty, was published by Harvard University Press in 2014. Her first novel, The Old Drift, was published by Hogarth Press (Penguin Random House) in 2019.

References

- American Dialect Society, "All of the Words of the Year, 1990 to Present," accessed April 19, 2018.[⤒]

- Bill Walsh, "The Post Drops the 'mike' — and the Hyphen in 'e-Mail,'" The Washington Post, December 4, 2015.[⤒]

- "Word of the Year 2015," merriam-webster.com.[⤒]

- Merriam-Webster, "-ism." merriam-webster.com.[⤒]

- Comedic rants about art and culture, "There Are Too Many Isms In Art And I'm Tired Of It," medium.com, August 28, 2017.[⤒]

- All emoji and their names and descriptions come from emojipedia.org.[⤒]

- "Word of the Year 2015," Oxford Dictionaries, November 17, 2015.[⤒]

- James J. Gibson, The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979), 127. Gibson first defined the term in The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966), 285. [⤒]

- Donald Norman, The Psychology of Everyday Things (New York: Basic Books, 1988). 9. [⤒]

- Theodor Adorno, "Punctuation Marks," The Antioch Review 48, no. 3 (1990), 300.[⤒]

- "Typographical Art," Puck, March 30, 1881, 65. Reprinted in Casey Chan, "The First Emoticons Were Used in 1881," Gizmodo, July 16, 2013.[⤒]

- Ambrose Bierce, "For Brevity and Clarity," The Collected Work of Ambrose Bierce, XI: Antepenultimata (New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1912), 387.[⤒]

- Alan Gregg, The Harvard Lampoon 112.1 (Nov. 1936): 16, cited in Vyvyan Evans, The Emoji Code: The Linguistics Behind Smiley Faces and Scaredy Cats (New York: Picador, 2017).[⤒]

- Ludwig Wittgenstein, Lectures and Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Belief (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 1.[⤒]

- Ibid., 2.[⤒]

- Ibid., 3-4.[⤒]

- Vladimir Nabokov, Strong Opinions, (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), 133-4.[⤒]

- Ibid., 62.[⤒]

- Sally Adee, "Specs that see right through you," New Scientist 2819 (July 5, 2011).[⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Jimmy Stamp, "Who Really Invented the Smiley Face?" Smithsonian.com, March 13, 2013.[⤒]

- Wikipedia, "Emoticon," accessed September 9, 2018.[⤒]

- "Original Bboard Thread in Which :-) Was Proposed," School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University.[⤒]

- Justin McCurry, "The Inventor of Emoji on His Famous Creations — and His All-Time Favorite," The Guardian, October 27, 2016. [⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Eyder Peralta, "Lost In Translation: Study Finds Interpretation Of Emojis Can Vary Widely," NPR, April 12, 2016.[⤒]

- Caroline Cakebreak, "Here's how to use Apple's Animoji — the new talking emoji that has your voice and facial expressions," Business Insider, September 12, 2017.[⤒]

- Druckerman, "Decoding the Rules of Conversation."[⤒]

- Peralta, "Lost In Translation: Study Finds Interpretation Of Emojis Can Vary Widely."[⤒]

- Caitlin Dewey, "Are Apple's new 'yellow face' emoji racist?" The Washington Post, February 24, 2015.[⤒]

- Monica Tan, "Apple adds racially diverse emoji, and they come in five skin shades," The Guardian, February 23, 2015.[⤒]

- Lizzie Plaugic, "Google's diverse emoji for women at work approved by Unicode Consortium," The Verge, July 14, 2016.[⤒]

- Vanessa Friedman, "The Fight for the One-Piece Swimsuit Emoji," The New York Times, July 31, 2018.[⤒]

- Samantha Sasso, "This New Emoji Is Getting Mixed Reactions On Twitter," Refinery29, December 14, 2017.[⤒]

- Kumari Devarajan, "White Skin, Black Emojis?" NPR, March 21, 2018; Andrew McGill, "White People Don't Use White Emoji," The Atlantic, May 9, 2016.[⤒]

- Sasha Lekach, "The real meaning of all those emoji in Twitter handles," Mashable, June 3, 2017.[⤒]

- Simone S. Oliver, "Are You Fluent in Emoji?" The New York Times, July 25, 2014.[⤒]

- Hannah Goldfield, "I Heart Emoji," The New Yorker, October 16, 2012.[⤒]

- Marlynn Wei, "Do You Know What That Emoji Means?" Psychology Today, October 26, 2017.[⤒]

- Nadja Spiegelman and Rosa Rankin-Gee, "Emoji Poetry," The Paris Review, August 18, 2017.[⤒]

- Harriet Staff, "Carina Finn & Stephanie Berger's Emoji-Code Translations Are 'Quite Brilliant,'" Poetry Foundation, February 4, 2014.[⤒]

- Lisa Gitelman, "Emoji Dick, or the Eponymous Whale," Post45: Peer Review, July 8, 2018.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Sternbergh, "Smile, You're Speaking Emoji," qtd. in Gitelman, "Emoji Dick, or the Eponymous Whale."[⤒]

- Benenson and Melville, Emoji Dick.[⤒]

- Xu Bing, Book from the Ground (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2014).[⤒]

- Gitelman, "Emoji Dick, or the Eponymous Whale"; Amanda Hess, "A Brief History of Emoji Art, All the Way to Hollywood," New York Times, July 28, 2017, quoted in Gitelman.[⤒]

- Ferdinand de Saussure, from Course in General Linguistics, excerpted in The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd edition, eds. Vincent Leitch et al. (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2010), 963.[⤒]

- Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 15.[⤒]

- Jacques Lacan, "The Agency of the Letter in the Unconscious," excerpted in The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, 2nd edition, eds. Vincent Leitch et al. (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2010), 1293, editorial footnote, 1294.[⤒]

- Ibid., 1297.[⤒]

- Jacques Derrida, "Signature Event Context," Limited Inc., trans. Samuel Weber and Jeffrey Mehlman (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1988), 21.[⤒]

- N. Katherine Hayles, "Virtual Bodies and Flickering Signifiers." October 66 (August 1993): 76, 71.[⤒]

- Courtney Saiter, "The Psychology of Emojis," The Next Web: Insider, June 23, 2015; Christina Peréz, "To Emoji or Not to Emoji? The Real Message Those Little Icons are Sending," Vogue, April 25, 2017. [⤒]

- Gitelman, "Emoji Dick, or the Eponymous Whale."[⤒]

- Rosanna Bruno, "The Slanted Life of Emily Dickinson," BOMB 131 (Spring 2015), quoted in Gitelman.[⤒]

- Lydia Belanger, "Why Durex Is Promoting an Emoji-Inspired Eggplant-Flavored Condom," Entrepreneur, September 6, 2016.[⤒]

- Colette Shade, "The Emoji Diversity Problem Goes Way Beyond Race," Wired, November 11, 2015.[⤒]

- Dewey, "Are Apple's new 'yellow face' emoji racist?"[⤒]

- Unattributed, pinterest.com.[⤒]

- Leslie Horn, "Emoji Cookies. I Repeat, Emoji Cookies," Gizmodo, November 28, 2012; Kathy MacLeod, "All the Emojis, Drawn," The Hairpin, March 27, 2013[⤒]

- Guy Trebay, Guy. "Digital Artist Yung Jake Scores With Emoji Portraits," The New York Times, July 26, 2017.[⤒]

- Beckett Mufson, "Yung Jake's Emoji Portraits of Celebrities," thecreatorsproject, January 14, 2015.[⤒]

- Chuck, Close, James. 2002. Oil on canvas, 276.23 cm x 213.36 cm. SFMOMA.[⤒]

- Mara Siegler and Emily Smith, "Sanaa Lathan confirmed as star who bit Beyoncé," Page Six, March 30, 2018.[⤒]

- Sianne Ngai, Visceral Abstractions," GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21, no. 1 (January 1, 2015): 34-5.[⤒]

- Ibid., 40.[⤒]

- Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Reason, trans. Martin Nicolaus (London: Penguin Books, 1973), 161.[⤒]

- Ngai, "Visceral Abstractions," 51.[⤒]

- Ibid., 35-36.[⤒]