Issue 2: How To Be Now

A wet and disheveled Chinese family walks into a fancy London hotel. The receptionist pretends not to see their reservation. After a bit of back and forth, he declares that the Calthorpe hotel has no rooms left. Why don't they look in Chinatown? Finally, the receptionist decrees that the three women and their three children must vacate the premises immediately. The conversation ends here. But the story ends an hour later when the family returns. Felicity Leong, daughter of Singaporean heiress Shang Su Yi, has bought the hotel. And her first executive decision as proprietress is to fire the receptionist.1

The prologue to Kevin Kwan's Crazy Rich Asians (2013) invites a thought experiment about contemporary fiction: what happens when a large, loud, genre-bending cohort of Asian "wealth porn" walks into a prestigious Anglophone republic of letters? These showy novels that thematize "Rising Asia" or "Global China" prompt us to contemplate the misalignment between the cultural economy of world literature (still routed through the nineteenth- and twentieth-century metropoles of New York and London) and a late capitalist world-system (in which transnational Chinese capital as well as the idea of "China" have played an increasingly dominant role). On the one hand, this misalignment reinforces an oft-noted international division of labor between the production of knowledge and the production of goods, the innovation of ideas and the conservation of culture. This division between innovation and conservation explains Rebecca Walkowitz's observation that the term world literature can refer both to "literary masterpieces" that "everyone in the world should read" and to "literary underdogs, those books produced outside of Western Europe and the United States."2 On the other hand, Crazy Rich Asians shows that these oppositions do not always hold. Global China novels such as Kwan's are "literary underdogs" that depict economic top dogs. They raise the question of how "Sinocentric world-system theories" impact the formation we call "world literature."3 Although Gayatri Spivak has cautioned against "equating dominant economic systems with cultural formations," the emergence of the "Asian values" discourse in the 1990s suggests a correlation between the two.4 Commenting on this discourse, Eric Hayot writes, "the right to assert the potential universality of one's cultural values derives almost directly from the perceived ability of those values to sustain economic development."5 But do "Asian values" indeed set the terms of worldliness when it comes to literature? In Kwan's Crazy Rich Asians trilogy, we encounter the dazzling exhibition of spending power and the profligate acquisition of real estate. If there is a moral compass to the trilogy — if there are indeed "Asian values" — it appears in the last installment when the protagonist saves his grandmother's palatial home by turning it into a Singaporean historical landmark. The remedy to the first two novels' unchecked capitalist desires, Kwan implies, is the preservation of tradition and the exploration of roots.

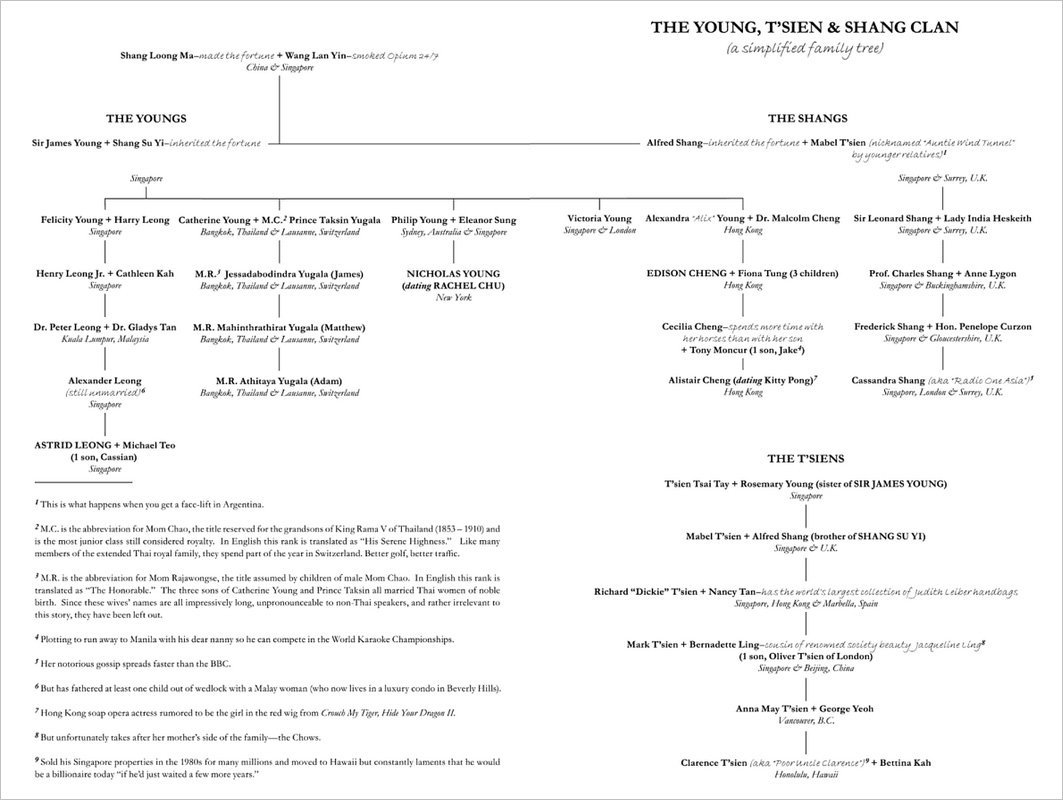

Crazy Rich Asians represents a growing corpus of novels that couch the extravagant accumulation of physical property and economic capital within an abiding nostalgia for local cultures and traditions. In this essay, I propose that the genre of Global China novels — in addition to the content of such novels — flouts both cultural origins (the preservation of tradition) and aesthetic originality (the innovation of ideas). To clarify this point, let us return to Kwan's opening hotel scene. This scene plays a genre trick. It not only parodies a reliable generic trope of anti-Chinese racism, but it also mocks the presumed genetic continuity between Singaporean Chinese and Chinatown Chinese. These moves are related. The more familiar stereotype that all Chinese are poor is as offensive to the sensibilities of Kwan's novel as the stereotype that all Chinese are are merely "Chinese." The hotel scene misleads because it presents crude racial discrimination emerging from an East-West dyad when the novel's true interests are the fine-grained discriminations — and rigorous hierarchies — among cultural, national, political, and linguistic notions of Chineseness. Ultimately, the genre of Kwan's novel — the genre of Global China — is anticipated not with the anecdote of anti-Chinese racism but with the elaborate paratextual family tree of the "Young, T'sien & Shang Clan" that precedes it. Complete with nicknames, status markers, net worths, hobbies, and footnotes, the "simplified family tree" presents a snapshot of the Singaporean Chinese diaspora located in far-flung metropolitan residencies, from Singapore to Hong Kong to Bangkok to Gloucestershire to Vancouver to Honolulu.

The question of what "Chinese" means amidst these taxonomic differentiations is a function of the novel's preoccupation with genre. In the Crazy Rich Asians trilogy, Chineseness gets worked out not through genealogy but through a hyperbolically gendered form of convention — that is, through an incessant novelistic chatter about décor, antiques, schools, newspaper columns, jewelry, and, above all, clothing. In Global China, gendered and generic norms are not so much "manners," the markers of class, as they are replicas, the cheap imitations that replace culture (both traditional values and aesthetic refinement) with convention.6 In Kwan's novel, this displacement of culture with convention is most apparent with Kitty Pong, the character whose true genealogical origins are uncertain because she is always performing a knockoff version of Chineseness. (Kitty is likely from Mainland China, but she pretends to be Taiwanese and later attempts to assimilate into Singaporean high society.)

Global China novels such as Kwan's present programmatic Chineseness from the seemingly authoritative perspective of an economically successful yet morally suspect diasporan. These novels include Hwee Hwee Tan's Mammon Inc. (2001), Annie Wang's The People's Republic of Desire (2006), Tash Aw's Five Star Billionaire (2013), Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan's Sarong Party Girls (2016), Yi Shun Lai's Not a Self-Help Book: The Misadventures of Marty Wu (2016), and Anna Yen's Sophia of Silicon Valley (2018). In such works, the hegemonic formation of Global China relies on genre rather than genealogy to substantiate a claim to Chineseness. With the phrase genre of Global China, I signal a likely unorthodox understanding of "genre" and "China," which the sections below will enlarge upon. For now, I'll simply say that my use of the term genre mostly closely aligns with what Lauren Berlant describes as "the marriage of aesthetic conventions and subjective conventionality."7 In the works listed above, the ethnic signifier "Chinese" is not cultural, biological, or national but conventional in the crudest sense. The term Global China, as I conceive of it, shares some affinity with what Shu-mei Shih calls the Sinophone. Both coinages underscore a distinction from Mainland China, and both seek to draw attention to "politico-cultural China" as imperial force. However, while the Sinophone emphasizes local specificity and enables critical expression for "subjects living under a colonial condition," "Global China" describes an emergent hegemonic structure that erases a politics of the local.8 In its predication on conventionality, the genre of Global China deprioritizes genealogical "roots" and instead propagates strict codes of gender normativity. Chineseness, then, is not a genealogical trait but a generically gendered paradigm adopted by geographically dispersed diasporans. This crudely conventional paradigm has three key implications. First, it inaugurates an economic world created in the image not of the commodity but of the counterfeit. Second, the generically conventional Chinese protagonist in this world is not an ethnic stereotype but an ethnic imposture. And third, the literary genre that best gives expression to this derivative Chineseness is not the ethnic ur-genre of the autobiographical novel but the sub-sub genre of the self-help novel.

Contemporary Anglophone novels that explore generic notions of Chineseness critically revise the underdog model of world literature. Because this model derives worldliness from cultural authenticity, its dominant genre is autobiographical fiction — the literary mediation of personal truth and anthropological fact. In post-1949 Chinese Anglophone literary works, personal histories are typically organized around mother-daughter relationships, thus accentuating the genealogical line between diasporic individuals and national origins. The motifs of tradition versus modernity, filiality versus individuality, have become such recognizable conventions within this body of writing that it is routinely dismissed for pandering to Western audiences.9 The Chinese Anglophone self-help novel, as we will see, is defined by its sub-sub generic relation to this earlier tradition of autobiographical fiction. By this I mean that the self-help novel is not only a branch of autobiographical fiction but that it is altogether constituted by and squarely "about" the merely derivative and crudely imitative. While ethnic and postcolonial scholars have alleged that the autobiographical genre sells well because it sells out, the self-help subgenre, with its frequent thematization of the counterfeit, takes selling to an illicit extreme. Compared to the autobiographical commodity, the self-help derivative is more conventional (in particular, more feminized) and less genealogical (that is, culturally inauthentic). Generically feminized and genetically ersatz, the self-help novel narrated by Chinese diasporans offers one avenue exploring the impact of Global China on Anglophone world literature.

To elaborate on these ideas, this essay will look to Malaysian Chinese novelist Tash Aw's Five Star Billionaire (2013).10 In Aw's novel, self-help is designed for a Malaysian Chinese readership based in Shanghai. The reader we meet, Phoebe Chen Aiping, attempts to remedy her attenuated relation to Chinese roots by seeking guidance from self-help books. Through Phoebe, we will see how the self-help genre negotiates genealogical dilution and gender normativity to facilitate the production of a Global China that is founded more on conventionality than on ancestry. As a genre that openly exploits the generic (as in the general), self-help amplifies the centrality of Chinese femininity and reveals the relative dispensability of Chinese genealogy to the circulation of hegemonic Chineseness.

Generational Genres of "China"

If the cult phenomenon of Kevin Kwan's Crazy Rich Asians trilogy signals an epochal shift, then this shift began at least fifty years ago — if not centuries ago when Europe discovered "China" as a "civilizational other," a "measure of the species."11 Within the history of twentieth-century Anglo-American cultural production, every twenty-five-odd years has brought a new pop cultural phenomenon that sublimates a generation's sentiments about "China." In 1958, the Broadway adaptation of Flower Drum Song, based on the 1957 novel by C.Y. Lee, threw the political profile and cultural authenticity of San Francisco Chinatown into the limelight to claim a version of Chineseness compatible with Cold War ideologies. Then, roughly twenty-five years later, the economic opening of Mainland China and the cultural emergence of high-achieving Chinese American "model minorities" endowed the mother-daughter relationships of the 1993 film The Joy Luck Club (based on Amy Tan's 1989 novel) with particular resonance. The recent Asian Americanization of the film adaptation of Crazy Rich Asians, a story largely about Singaporean Chinese, not only inserts American race relations and Chinese intergenerational relations into global circuits of capital. It also shows how in 2018, the idea of Global China has accrued more hegemonic pull than Mainland China (the officially recognized China), the Republic of China (once the only China in the Free World), or even Overseas Chinese (the bridge figures among transnational Chinese capital networks in the 1980s and 1990s).12 Since the 2000s, in Anglo-American culture and politics, Global China has eclipsed all other Chinas and now anchors the geopolitical imaginary of "the Pacific Rim."

An interesting coincidence: twenty-five years is also the life cycle that Franco Moretti attributes to the "generational" genre. Drawing on Fernand Braudel's work, Moretti identifies three temporal frames through which we comprehend "historical flow": "the short span [of the event] is all flow and no structure, the longue durée all structure and no flow, and cycles are the — unstable — border country between them." Cycles or waves, then, are the "temporary structures" lasting roughly twenty-five years through which Moretti analyzes "genres" — literary units defined as "morphological arrangements that last in time, but always only for some time." Moretti's question about whether "this wave-like pattern [is] a sort of hidden pendulum of literary history" hints at the usefulness of genre for the tricky task of periodization, especially in a historical moment with more momentum than momentousness, more indecipherable shapes than settled morphologies.13 Given the generational representations of "China" surveyed above, Moretti's meditations on the cyclical nature of genre help to clarify what Giovanni Arrighi, also following Braudel, has conceptualized as "cycles of accumulation." What can novelistic interpretations of Global China, in their preoccupation with the generic, tell us about the nature of global power during America's "autumnal" period? In Arrighi's longue durée, "autumn" designates a transition of power from one empire to another. Autumn is, as it were, perennial: it came in the 1560s, the 1740s, and the 1870s, and it has been in the United States since the 1970s. With remarkable consistency, this autumnal period has been marked by financialization, deficit spending, and warmongering, even as it has been experienced as seeming prosperity. In theorizing the relocation of imperial power, Arrighi views Asia's increased economic influence as a counterpoint to and a symptom of America's militaristic pursuits. He writes, "the most important unintended consequence of the Iraqi adventure has been the consolidation of the tendency towards the recentering of the global economy on East Asia and, within East Asia, on China."14

Arrighi's prognosis that America's autumn may in fact coincide with China's spring allows us to evaluate claims that theories of realism are forged during periods of civilizational uncertainty and hegemonic transition. Jed Esty, for example, argues that "realism wars erupt . . . at the site of struggle between norms of finite social description and half-articulate dreams of expansive political projection."15 Such "realism wars" debate how to represent a historical present that is sliding into an unpredictable future. Esty implies that the concept of Anglophone world literature is one such "realism war" insofar as it demonstrates how "English studies as a discipline" is attempting to "transnationalize itself beyond its traditional roots in British and American cultural hegemony."16 Global China novels offer an especially illuminating angle into this "realism war" of world literature since they stage the contradictions of hegemonic change. Namely, they testify to the continued supremacy of a global intellectual property regime while depicting the shift of global production and consumption to a region shadowed by Chinese imperial ambition. Whether these novels depict the heiresses of Singapore, the nouveau riche of Mainland China, "model minorities" from the United States, or aspirational migrant laborers from Malaysia, they articulate Global China's newfound significance in relation to the strength of its informal economy — the circulation of counterfeit and pirated goods. Given the preponderance of novels that take the informal economy as a figure for Asia's fast-track ascent from Third World backwater to economic hub, I'm inclined to view the realism war emerging from Anglophone representations of Global China as concerning the intellectual property status of the publications that we call "world literature." Joseph Slaughter's essay "World Literature as Property" arrives at a similar thesis, positing that intellectual property, rather than physical property or spatial territory, motivates contemporary neocolonial expansion.17 My concerns in this essay are conditioned by Slaughter's property model of world literature. My focus, however, is how the larger global imaginary of international property rights (IPR) and its localized manifestations in contemporary Anglophone literature are expressed as a problem of genre.18

Moretti's evolutionary modeling of genres through "trees" makes explicit the frequent analogizing of literary genres with reproductive life — with generation, genus, gender, and genealogy. My interest in femininity and Chineseness makes genre's etymological kinship to gender and genealogy especially relevant. Self-help presents us with a double injunction for investigating the genre of Global China. One injunction is to heed Wai-chee Dimock's call to "put far-flung kinship at the center of any discussion of genre" — that is, to ask how genre articulates "Chineseness" from several generations removed. The other is to take seriously what Lauren Berlant identifies as genre's co-articulation of "aesthetic conventionality" and "sexual normativity" — or, to contemplate how normative femininity functions as an antidote to genealogical distance.19 As we will see, in the self-help novel, the intensification of the generic discloses a symptomatic relation between feminine conventionality and ethnic ambiguity. Specifically, the self-help genre dramatizes how gendered prescriptiveness compensates for genealogical weakness.

Knocking off the Autobiography

As with perhaps all subgenres, self-help can be viewed as a "knock off" of other more prestigious genres. The most significant of these prestigious genres is the ethnic autobiography. Although the minority autobiography has long been known to dole out local guidance to global audiences, it is also a genre deeply interested in its protagonist's quest for guidance. V.S. Naipaul's The Mimic Men (1967), for example, introduces a notion of self-help that inspired Homi Bhabha's influential theory of colonial mimicry. Naipaul's colonial subject seeks out "help" by consuming the literatures, cultures, and styles of the metropole. Another famous autobiographical novel, Maxine Hong Kingston's The Woman Warrior (1976), portrays the search for genealogical "help." The Woman Warrior is predicated on the "talk-stories" that the narrator's mother dispenses, not for their entertainment value but for their practical applicability. Particularly in the case of Kingston, autobiography essentializes the link between genre, gender, and genealogy. Genealogical reproduction explains why the intergenerational saga of mother-daughter has become so pervasive within Chinese and Chinese Anglophone writing. Set against national turmoil, the mother-daughter personal story helps secure the symbolic connection between autochthonous culture and traditional woman, genealogy and gender. Prominent works in this vein include Tan's The Joy Luck Club (1989), Jung Chang's Wild Swans (1991), Anchee Min's Red Azalea (1993), and Adeline Yen Mah's Fallen Leaves (1997).

If autobiography is a strong mode of identity production, one in which we are accustomed to finding an unadulterated ethnic line, then the self-help genre in Aw's Five Star Billionaire operates as a "weakly designative and weakly determinative" mode for engaging the Chineseness of Malaysian Chinese returning "home" after generations of "sojourning."20 Chinese men began migrating to the South Seas (Nanyang) as early as the Tang Dynasty. The highpoint of this labor migration took place during the nineteenth century, contemporaneously with the arrival of Chinese men in the Americas, Australia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands. Nanyang Chinese and other Chinese migrants emphasized "sojourning, not permanent emigration," E.K. Tan writes. "It was simply assumed that everybody abroad wanted to return." Virulent anti-Chinese discrimination in places such as Malaysia, Tan adds, "is responsible for the inseparable ties between the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia and the motherland, China." "Even today," he proposes, "the notion of 'home' for most Chinese communities in Southeast Asia is still strongly linked to the geographical locale, China."21 Yet, Aw's novel presents the opposite of what Tan describes. Aw's Malaysian Chinese characters experience Shanghai through a culturally specific mode of capitalist alienation. "Only in China could people deal so swiftly with the past; only in China could they forget and move on without blinking," one character observes (283). The "homecoming" for Aw's characters exposes the genealogical fallacy of Chineseness. In lieu of a genealogical line, he presents Chineseness as a generic paradigm. Self-help in Five Star Billionaire is a genre tailored for a Malaysian Chinese reader who, in returning to the "homeland," desperately yearns to be more legibly "Chinese." This genre of self-help, then, is what Dimock might view as one of the Chinese autobiography's "second and third and fourth cousins."22 Self-help, in other words, is not the organic source of Chinese authenticity but a template of Chineseness sought out by Malaysian Chinese migrants, who are attempting to pass as their more legible Mainland or Taiwanese "cousins." A self-help guide is what allows Aw's Malaysian Chinese imposters to transform their "weakly determinative" Chinese genes into a recognizable Global China genre.

This notion of Global China as genre is closely related to a capitalist-inflected, mass-produced notion of the generic. Lisa Rofel has observed that "neoliberalism" is the most intelligible in the global south:

Only because of these southern national projects, with their insistency and vigor, does anyone in the north even notice neoliberalism. If northern progressives worry, they have learned to do so from the world-making grasp of neoliberalism brought to their doors by north-south collaborations.23

The key axis of "north-south collaboration" that subtends the generic production of a Global China in Five Star Billionaire is the global IPR regime. If illegal copies represent "the evils associated with the capitalist system" but made manifest "more hastily and dramatically," then it is no surprise that IPR infractions have made China so iconic of capitalism's perils.24 In Aw's world of capitalist instrumentality, an IPR regime seems to have displaced conventional modes of territorial, cultural, and economic imperialism. This is a notable contrast to Aw's previous novels Silk Harmony Factory (2005) and Map of the Invisible World (2009), which focus on European colonialism and postcolonial civil unrest, respectively. Five Star Billionaire does not depict its characters in Europe or North America (though some were educated there), nor does it devote significant attention to Western characters in Shanghai. In this novelistic universe, Euro-America appears almost exclusively as free-floating proper nouns — brands, authors, texts, and universities. Despite the apparent absence of "the West," therefore, a global regime of intellectual property is a powerful driver of desire in Five Star Billionaire.

Even though brands, artists, and artwork circulate prolifically in Aw's novel, his characters chase not the real things but their cheaper and more expedient copies. These characters are all deceitful impersonators and aspiring artists; they express their desire to be someone other than themselves through an artistic impulse gone awry. Pop idol Gary Gao's rise to fame makes him a media sensation without a distinct personality; his fall from fame, meanwhile, renders him indistinguishable from various "Gary" impersonators. Gary's career reboot begins with his adaptation of a folk song his mother used to sing. He jokes: "Like everything in life these days, I suppose you could say it's a copycat — a fake" (294). Justin Lim, the face of Overseas Chinese dynastic wealth, possesses a superb business aptitude but a vocabulary "weighed down by platitudes" (97). In order to impress his childhood crush, he fantasizes about running an art gallery or moving into film production (281). Ironically, Yinghui Leong, the artsy intellectual Justin admires, has in adulthood become a no-nonsense entrepreneur. In Yinghui's eyes, the tragedy is not that she has lost her artistic sensibility but that success has prevented her from "remaining gentle and feminine — a real Asian woman" (50). Phoebe and Walter, the two characters to whom I devote the most attention, represent extreme forms of ethnic typologies that manifest as social pathologies. They literally take on new names and new identities. They are also the most avid readers and producers of self-help.

From Autobiographical Authorship to Self-less Self-Help

The relation between autobiography and self-help appears most explicitly in Aw's chapters on Walter. While Five Star Billionaire adheres to a strictly third-person perspective with each chapter following an individual character's storyline, Walter's chapters, excerpted from his bestselling self-help book Secrets of a Five Star Billionaire, proceed in a first-person and second-person voice, emphasizing the difference between the self-expressive I and the imitative you. These chapters are framed as "case studies" and "how-tos" — for example, "How to be a Millionaire," "How to Manage Time," "How to Structure a Property Deal," and "Case Study: Human Relations."

When we first meet Walter, he is a property developer who has written a slate of financial self-help books. His status as real estate mogul and self-help author hints at the intimate relation between real property and intellectual property consecrated by modern copyright law.25 But Walter's real estate portfolio and his authorial profile emerge from a haze of suspicion — not from a room of one's own or the soil of one's mind. Reflecting on his childhood in rural Malaysia, Walter remarks: "Nowadays, I hear liberal, educated people refer sympathetically to such ways of life as 'hard,' or even 'desperate,' but I prefer to think of it as creative" (59). For Walter, creativity always possesses an illicit aspect. It is what allows him to fulfill his childhood ambition of becoming "not just comfortably well off but superabundantly, incalculably wealthy" (xi).

Walter's euphemistic use of the term "creativity" allegorizes Mainland China's alleged cultural and political incommensurability with a global IPR regime. This incommensurability has been subject to considerable discussion. For example, Peter Ganea and Thomas Pattioch conjecture that imperial China "could not possibly generate a legal system that supported outstanding creative endeavour" due to a pervasive "lack of a legal consciousness."26 In less patronizing terms, William Alford draws a contrast between the emergence of patent and copyright law to protect individual property rights in Europe of the eighteenth century and the Chinese imperial government's attempt to preserve social equilibrium through the regulation of information dissemination.27 The contemporary spotlight on postsocialist China's IPR infractions bears out a more general moral unease with the repercussions of China's marketization and in particular with its international trade policies. Hence, while Asiatic modes of production have long been characterized as corrupt, Walter represents a variant that is specific to the stigmatization of Mainland China and other Asian states within a burgeoning creative economy. There is a correlation between the outsized desires of someone like Walter to be "superabundantly, incalculably wealthy" and the Chinese economy's "addict[ion] to piracy and other IPR violations."28 Like the self-help entrepreneurs we find in Mohsin Hamid's How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia (2013) and Aravind Adiga's The White Tiger (2008), Walter is not Aihwa Ong's Western-educated "flexible citizen" whose cosmopolitan lineage and transcultural fluency enable his success.29 Rather, Walter has attained his success through what he delicately terms "the 'university of life'" (83).

The deceptive element to Walter's "creative" endeavors appears most poignantly in his presentation of self-help as philanthropic selflessness. He tells us, "part of the purpose of this book" is to herald "a gracious, generous billionaire." Rather than stamp a book with his actual personality, Walter introduces a distinct and exceptional self that relies on a number of deceptions, qualifications, and retractions (83). For example, he notes that "when I read an article about myself, even I recoil at the seeming callousness of my financial maneuvering...What a dreadful life this Walter Chao must have, I think: Imagine being him. Often I forget that he is in fact me" (84). To an extent, these tensions between the author who helps others and the author who profits from others are inherent to the financier autobiography. Leigh Claire La Berge describes how works by Donald Trump, Ivan Boesky, and T. Boone Pickens are always balancing "content, that which may be narrated and represented, and information, that which is profitable." These financiers-turned-authors repeatedly insist that their "texts' manifest aim is not profit" — a move that "makes them more insidious." La Berge writes, "While they are not literally making money for their authors, their authors' self-aggrandizement cannot be separated from their accumulative dispositions." An autobiographical personality cannot be disaggregated from a brand name; in fact, each can only enhance the other's value.30

In Walter's case, there is an ethnic element to the fraudulence of self-denying generosity and self-inflating financial accumulation. The secret that he hides is not merely financial fraud but the fraudulence of identity itself:

I write these [self-help books] not to make money, you understand, but to share the map of my success with ordinary people in need of inspiration. Nor are these books an outlet for vanity or a search for deeper recognition: Most of them have been written under various pseudonyms, including the multimillion-bestselling Secrets of a Five Star Billionaire.

So those of you who think you know me — think again (84).

Walter emphasizes his use of pseudonyms. He claims to rebuff the property rights normally accorded by publication and to contribute to the public reservoir of knowledge without any returns for himself. By divorcing his portfolio of real estate properties from his profile of intellectual property, Walter marks his difference from those who publish to extend a proprietary project of self-branding. For someone like Trump, the generosity of providing financial self-help putatively offsets the greed of accumulating capital for himself. His immorality arises from, among other things, saying one thing and doing another. For Walter, however, the moral binary is presenting a real identity versus circulating aliases. The gesture of selflessness is a kind of fraudulent generosity for which the true crime is perhaps not the insincerity of moral posturing but the racialized deceptiveness of the Oriental imposture.31 Indeed, throughout Five Star Billionaire, we encounter a range of personas that all nominally belong to Walter but seem difficult to reconcile with a consistent character. To the flesh-and-blood reader, Walter appears as a manifestly untrustworthy tycoon who talks too smoothly and too fast. As Phoebe's boyfriend, Walter is a wealthy dupe given to excessive sentimentality and awkward conversations. With his business partner Yinghui, Walter is a well-read, confident flatterer who uses romance to steal all her money. And, finally, as a relic of Justin's past, Walter is a poor rural bumpkin ignorant of the realities of business.

In a sense, these multiple personas combine to make Walter the personification of Ong's stereotypically corrupt "border-running Chinese executive" who embodies "Pacific Rim capital."32 In this account of citizenship, a prodigious flexibility is precisely what makes identity difficult to pin down. But, as I indicated above, the flexibility of a cosmopolitan or diasporic identity is different from Walter's impersonation of multiple identities. The fraternal model of Chinese diasporic network capitalism and the paternalist model of state-protected capitalist development are presented through other characters in Aw's novel, who function as foils to Walter.33 For example, Justin, a businessman with considerable regional mobility, is the picture of the fraternal model. Walter, by contrast, is more of a nomadic pirate than a diasporic family man. Whereas both Chinese familial capitalism and organic artistic creation have used "roots" to metaphorize origins and originality, Walter's self-help enterprise is erected on a kind of rootlessness that intertwines ethnic deception with aesthetic derivativeness.34 For La Berge, self-help is a genre of "capitalist realism," by which she means "the realistic representation of the commodification of realism."35 Walter's narrative transforms the meaning of "realistic" by displacing the commodity with the counterfeit or, phrased differently, the authentically autobiographical self with the contrived selflessness of self-help.

Walter's use of the self-help genre to narrate his development from an impoverished Malaysian boy into a successful Asian businessman is particularly striking in this regard. In the second half of Five Star Billionaire, the presence of a self-help "you" dramatically recedes from Walter's chapters as an autobiographical "I" takes over. Here, we meet a younger Walter who could not be more different from the heartless property developer. This difference is heightened by the fact that Aw interweaves the narrative of Walter's childhood with the narrative of his present-day treacheries. The young Walter, a straight-laced realist, is the antidote to his father, a "fantasist" given to wildly improbable development projects. Young Walter begs his father to "give up on his venture," to "cut our losses," and "buy a small place somewhere." They could both "could get a job, nothing special," and they "could live a simple life, just like before" (213-214).

If capitalist realism is an aesthetic that transacts as well as represents — consider the case of "a film about finance" that draws "attention to the financing of film"— then Walter's attempt to "knock off" the autobiographical brand draws attention to the replacement of authenticity with conventionality.36 The result is to make a Chinese identity more a function of a programmatic model than a pure bloodline.

Maternal wisdom

The most significant testament to the bloodlessly programmatic nature of Walter's Chineseness is his use of an authorial double: a traditional Chinese mother. Walter's booming self-help enterprise of books and DVDs employs not only a pseudonym but also a proxy, that of "a mature woman" who "could look beautiful and successful even when no longer in her first springtime" (4). This woman, whom Phoebe glimpses on a television in a Guangzhou noodle shop, emits a distinctly maternal aura. She gives Phoebe "the feeling of courage" with her "words about not being afraid of being on one's own, far from home." Having just left her native Malaysian village to seek the storied opportunities of Mainland China, Phoebe vows that the moment she has money, she will buy not "an LV handbag or a new HTC smartphone" but the woman's "words of wisdom" (4-5).

Walter's surrogate allows him to transmit materialistic self-help through maternal wisdom, thus exploiting the symbolic incarnation of genealogical roots and the traditional custodian of Chinese culture. In a sense, this scenario presents a parallel to the 1959 Douglas Sirk film Imitation of Life, as read by Lauren Berlant, in which a white woman achieves economic emancipation by trading on the embodied erotics of a racially marked mammy figure. As with the mammy figure in Sirk's film, Walter's maternal trademark "triangulates with the customer and the commodity, providing what W.F. Haug calls a 'second skin' that enables the commodity to appear to address, to recognize, and thereby to 'love' the consumer."37 In branding self-help through this female proxy, Walter transforms Chineseness into a "second skin" that allows him to forge a "love" connection with Phoebe that promises the practical wisdom and therapeutic comfort of a traditional yet stylish Chinese mother. He thereby not only acquires for himself the prosthetic body of Chinese authenticity, but he also generates consumer desire for Chineseness as a second skin.

Walter's manipulation of self-help and autobiography to legitimate the commodity of Chineseness through maternal wisdom is, in a sense, nothing new. The maternal figure is the linchpin to those international and intergenerational sagas that I mentioned earlier. The Chinese mother was also at the center of the controversy surrounding Amy Chua's Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother (2011). Chua has repeatedly claimed that Battle Hymn is not a self-help guide but an autobiography, an interesting update of Maxine Hong Kingston's insistence that The Woman Warrior is not an autobiography but a novel. The genre controversy surrounding Battle Hymn shows that the parameters of Chineseness may be shifting. Chua employs a novelistic writing style and tempts us to read Battle Hymn as "an epic novel about mother-daughter relationships spanning several generations, based loosely on my own family's story."38 But Chua ultimately displaces the enduring problem of the ethnic novel, suggesting that the authenticity of Chineseness must be decided not through a fiction/nonfiction dichotomy but a blood/genre dichotomy. Can Chineseness be a template rather than an inheritance? Like Walter, Chua is several degrees removed from "China." Her parents were born in Mainland China but grew up in the Philippines. Chua herself was born in Illinois and raised in California. Yet Chua has no qualms about viewing herself or her two Chinese-Jewish-American daughters as Chinese. This is because her understanding of Chineseness is not based on blood or culture:

. . . we stuck with the Chinese model because the early results were hard to quarrel with. Other parents were constantly asking us what our secret was. Sophia and Lulu were model children. In public, they were polite, interesting, helpful, and well spoken. They were A students, and Sophia was two years ahead of her classmates in math. They were fluent in Mandarin. And everyone marveled at their classical music playing. In short, they were just like Chinese kids.

Except not quite.39

To Chua's alarm, no one other than herself views her daughters Sophia and Lulu as Chinese. But Chua's emphasis on producing "model children" through "the Chinese model" accounts for her paradoxically "loose" interpretation of Chineseness. As an opening disclaimer to the book, she writes, "I'm using the term 'Chinese mother' loosely. I recently met a supersuccessful white guy from South Dakota . . . [whose] working-class father had definitely been a Chinese mother."40 In adapting the mother-daughter intergenerational autobiography to present a Chinese model of parenting, Chua downplays the genealogical purity and phenotypic expression of Chineseness and makes a strong appeal to generic convention. Her conflation of extreme parenting with Chinese mothering turns rules, discipline, and rigor into generically "Chinese" attributes.

Chua's ability to lay claim to the authority of the "Chinese model," to the point where she completely rewires our intuitive sensibilities about who qualifies as a "Chinese mother," is the flip side of Walter's self-help enterprise. Chua's case is that anyone can be a Chinese mother. Walter's is that the Chinese mother as guru can make anyone Chinese. In turning a maternal persona into a working template of Chineseness, Walter suggests that the displacement of the genealogical by the generic requires a paradigm of gendered conventionality. This paradigm is at work in different ways in recent self-help novels narrated by tiger daughters. Marty Wu, the protagonist of Lai's Not a Self-Help Book uses self-help books to make sense of her Taiwanese mother's parenting style: "I read about it. It's, like, a tiger mom thing. Like, you know, really high expectations, and Asian culture saying you shouldn't, like, praise your own kids too much."41 By contrast, Sophia Young from Yen's Sophia of Silicon Valley is a coincidental yet entirely appropriate namesake of Chua's actual daughter. In this autoethnographic novel about Pixar, Apple, and Tesla, tiger wisdom becomes a workplace resource: the narrator's experiences growing up under a neurotic Taiwanese immigrant mother, we are led to believe, have made her exceptionally well equipped to manage the idiosyncrasies of wide-ranging corporate personalities. Throughout Yen's novel, Chinese motherly reminders complement the Zen aphorisms of a thinly fictionalized Steve Jobs.

In these quasi-autobiographical and quasi-pedagogical works, Chineseness appears as a generic model. This template version of Chineseness, given prosthetic "roots" through the figure of the mother, does follow the autobiography in drawing on the authority and authenticity of an author whose life materials provide lessons in the guise of stories. But it is notable that both Chua and Yen explicitly narrate the act of setting aside intergenerational sagas such as Chang's Wild Swans, as if to inaugurate a new convention of Chinese diasporic writing. If "the generic markers of diasporic Chinese women's life writing" were at one time "persecution and suffering under despotic Asian regimes," the generic markers now tend to be an orientation to the future (rather than the past) and to the self (rather than the family).42 To quote Singaporean Chinese Hwee Hwee Tan, herself a chronicler of the aspirational new woman, "most Asian women I know are more like Bridget Jones than Madame Mao."43

The Sub-Sub Self

The self-help genre's most significant distinction from autobiography is its orientation toward the reader rather than the author. In this respect, self-help functions something like a pivot between the genealogical preservation of autobiography and the individual reinvention of "chick lit." Numerous accounts of "women's genres" point out the purposeful conflation of reader with consumer. The lowness of such genres, according to Linda Williams, resides not only with "the fact that the body displayed is female" but also with the passivity of the reader or viewer who "is caught up in an almost involuntary mimicry."44 Passive responsiveness, the quality that putatively makes these low genres effective, plays into a generic predisposition for guidance and advice. Caroline J. Smith, for example, views "chick lit" as an extension of nineteenth-century American fiction, magazines, domestic manuals, and self-help books that "present their readers with prescriptive instructions regarding how to live their lives." These prescriptive genres, she writes, use "the second person to appeal to their readers and to incite those readers to action."45 A second-person readerly orientation produces a sub-sub self, one derived from a generic and gendered norm. This sub-sub "you" of women's genres also contributes to the minorness and mundaneness of such genres, which are invested in the "robust production of subgenres."46 The proliferation of self-help in both fiction and nonfiction as well as across diverse media such as books, films, newspapers, and magazines breaks up the conventional quest narrative of heterosexual marriage into everyday, step-by-step practices of self-improvement and self-management. The sub-sub aspect of self-help lies in both the mundane and the derivative, the piecemeal work of self-making through the approximation of social norms as doled out by (often motherly) advice columns.

In Five Star Billionaire, the self-help genre encodes what Berlant might deem the "formalism" and "normalism" of Chinese femininity.47 Yet through the specific case of a Malaysian Chinese migrant laborer illegally working in Shanghai, Aw presents a conception of genre that transforms Berlant's notion of "normalism" — the ideal type that becomes nature and routine — into the social stigma of illicit imitation. As an extreme case of the formal, the self-help genre evokes the abnormal, perhaps even the pathological. Because self-help is a reader-centered genre, the character in Five Star Billionaire who best exemplifies its generic qualities is Phoebe. Phoebe idealizes an organic root model of Chinese tradition as represented by motherly expertise, but in practice she implements a rote, shortcut model of Chinese convention through self-help. The significance of the self-help genre — of generic self-help — for Phoebe is the promise of personal reinvention through genealogical reconstruction. The opening incident that sets off Phoebe's quest for a palatable Chineseness is her theft of a Shanghai local's identity card. This quest then entails purchasing counterfeit products such as a handbag and "cheap counterfeit copies" of self-help books such as Sophistify Yourself and Why Men Love Bitches (116). The generic trope of the fake bag and the generic template of self-help are related, in part because both bear a metaphorical and causal relation to the derivative person.

The knockoff handbag is a prevalent conceit in Global China fictions.48 Unlike the pirated book or film, which typically functions as a symbol of individual courage and artistic expression against state censorship, the counterfeit bag is completely devoid of political cachet. Aligned with self-help imitation rather than authentic self-expression, the cheapened purse connotes the political apathy and cultural banality of consumerism while also allegorizing the corrupt, illegal, and imitative tactics of a "pirate nation." This term pirate nation is most frequently used to describe Mainland China, but the "monogramouflage" of the purse also connotes cultural derivativeness more generally. Indeed, "Monogramouflage" was the name of a 2008 display at the Brooklyn Museum that simulated the appearance of Louis Vuitton handbags on sale in Chinatown. Where the Louis Vuitton bag is the commodity that configures a generic norm, its counterfeit pathologizes the norm into the derivative, the genre into the subgenre.

The version of self-help that Phoebe pursues in Five Star Billionaire is a gendered genre of exaggerated conventionality that veers into the illegal and immoral territory of the derivative. Whereas the culturally authentic autobiography of Chinese diasporans draws out the link between genre and genealogy, the Global China that emerges through Phoebe is one in which conventionality, in the hyperbolic form of the counterfeit, displaces the blood-based model of ancestry. Phoebe vows to "become a woman of infinite class" by subscribing to "the following rules" — rules that she dutifully jots down into her "Journal of My Secret Self":

I must improve my appearance; I must dare to dress like a slut.

I must exercise my body; to be fat is not acceptable.

Sleep - five hours a day is enough.

. . .

Use men just as they would use you.

Lying to a man is okay, as long as you get what you want.

Do not stick only to one man.

Being nice is your mom's job - and look where it got her.

Do not grow old waiting (116).

Walter's Secrets of A Five Star Billionaire offered not secret techniques but instead underscored the deceptive dimension of a billionaire's secret identities. In Phoebe's case, a "Journal of My Secret Self" is not a pipeline to some authentic secret interior but instead displays the relation between reading counterfeit self-help and crafting a fraudulent, imitative identity. As suggested by the echo between Phoebe's private diary "Journal of My Secret Self" and Walter's bestselling publication Secrets of a Five Star Billionaire, these two characters are intimately related, not just as a romantic couple (which they come to be) but as a reader-author unit. Walter is to deceitful creativity as Phoebe is to superficial imitation; he writes self-help books, and she devours and reproduces them. Phoebe's journal entries largely operate in the speculative mode. They detail who she hopes to be: a daring slut, a manipulative liar, and a sophisticated bitch. The shift from the first-person "I must" to the second-person imperative mode recurs throughout the novel as Phoebe uses the language of self-help to chide herself: "Phoebe Chen Aiping, why are you so afraid all the time? Do not be afraid! Failure is not acceptable!" (4). This wavering "I," which is always being subsumed by a derivative yet speculative "you," is reminiscent of Randy Martin's claim that reading self-help is "a means of purging in the self."49 Self-improvement through self-help is not merely "a way of maximizing your potential of getting what you want." It is, to adapt Sara Ahmed, an expunging of the "authentic" self for the purpose of obtaining a social good — a norm, ideal, or stereotype that has become economized within the cultural idiom of consumption.50 Phoebe's journal documents this process of purging the "I" by revealing not who she is but what she reads. Her sub-sub "you," in contrast to the possessive "I," is the most sexualized self, based on the most essentialist and retrograde notions of woman, and it is also the most pirated self, reproducing verbatim the language of self-help books.

"Eight out of 10 bestsellers in Asian bookshops are self-help books," Aw once noted in an interview.51 This implicit profiling of the modern Asian subject as a reader-consumer helps explain why the self-help genre has been associated with "women's culture" on the one hand and "Global China" on the other. Self-help is for those stricken by an excess of impressionability and imitativeness. In Tan's Sarong Party Girls, a novel about Singaporean Chinese, both the narrator Jazzy and her boss Albert seek out self-help. Although the writings of Sun Tzu, Lee Kuan Yew, Margaret Thatcher, and Mao Zedong are all invoked as "help," the most useful resource turns out to be the most generic rather than the most famous or the most powerful: "I think I am the only one in this whole building who knows that of all these books [Albert] actually has only read one: How to Win at EVERYTHING."52 Novels such as Tan's make the gendered division of self-help production and consumption especially stark. In contrast to entrepreneurial boss figures such as Tan's Albert and Aw's Walter, the reader-consumer figure is akin to what Rofel terms the "desiring subject."53 Such subjects are often young women who negotiate cosmopolitan belonging through brand name consumption and sexual commodification.

In the context of postsocialist China, the state has a strong stake in binding sexual passions to consumerist passions. The overwhelming presence of such passions, Rofel maintains, corresponds with the absence of identifiably political passions, thereby serving as a counterpoint both to a prior era of Chinese socialism and to more recent pro-democracy movements. According to Rofel, the postsocialist allegory that Maoist androgyny inhibited the proper expression of gendered selves has allowed the Chinese state to promote the twinned emancipatory promise of market liberalization and sexual normalization: the "shaping of new gender identities in terms of human natures" is part and parcel of the statist and globalist vision of "economic development as having 'natural' rhythms and mechanisms."54 In this postsocialist allegory, modernity requires relicensing essentialist gender identities in conjunction with mobilizing a narrative of sexual and gender liberation from a repressive state. The literary counterpart to postsocialist allegories are works such as Wei Hui's Shanghai Baby (1999; trans. 2001) and Mian Mian's Candy (2000; trans. 2003). These works often feature an aspiring or successful writer who views bodily exposure and conspicuous consumption as the analogues to authentic self-expression. What distinguishes Aw's Five Star Billionaire is its focus on the personas Wei Hui casts as "fake linglei."55 The linglei are a "tribe" defined by a "bizarre romanticism and genuine sense of poetry." The "fakes," meanwhile, "imitate us in every way they can, from clothes and hairstyle to speech and sex" (235). They are "foreigners," "vagabonds," "flashy and superficial" people who "just disappear like bubbles" (39-40). If Wei Hui's characters represent the real lingei, the inner circle of artsy and cosmopolitan Shanghainese, then Aw's Malaysian Chinese are the "fakes" and "foreigners" who aspire to be them. Although one might view both sets of characters as bound to formulaic social types, in Aw's case, this formal limitation manifests as an overreliance on illicit rather than conspicuous forms of consumption for social mobility.

From Mimic Man to Knockoff Girl

As a knockoff of the autobiography's authentic self, the sub-sub-self of self-help intensifies and perhaps even satirizes the conflation of "aesthetic conventionality" with "sexual normativity" that underpins Berlant's theory of genre. In Five Star Billionaire, self-help gives generic expression to the "stereotypical association between counterfeit production and female consumption" but with the added emphasis on the ethnicizing potential of gender normativity.56 Aw contrasts this programming of ethnicity through generic femininity with the kinds of colonial mimicry to which we are more accustomed. In fact, the novel's true stereotypes may not be the characters who are unapologetically conventional but those who possess an "artistic temperament." One of the latter is Justin's brother C.S. Educated in Philosophy at University College London, C.S. diagnoses the debased quality of Asian capitalism from the perspective of Western-educated diasporans: "Corruption is quite comforting, really," he says, "it suits us, suits the Asian temperament" (236). C.S. and his girlfriend Yinghui (a sociology major at the London School of Economics) devote their youth to attending "talks by obscure Eastern European writers on such topics as 'Ideas of Beauty in Post-Communist Guilt'" and "lectures on Sanskrit texts at the Brunei Gallery." On their travels, "they made sure they found interesting fringe-theater productions or alternative-music venues, and they never bought anything outside local craft fairs." The one Chinese literary event they attend concerns a novel that "contained no fewer than seven scenes of heterosexual anal sex and four instances of sadomasochism, which led to a furious audience debate on the nature of censorship and prudishness in Asia" (99). In one telling scene, C.S. watches the Kuala Lumpur news with Yinghui while reading a book entitled Western Aesthetics. When Yinghui laments the exhortations of a "fat-ass minister, behaving as if he really cares about the floods," C.S. responds: "You grew up in this shit; you of all people can't say you're surprised by it" (235).

"Artistic" characters such as C.S. and Yinghui champion exaggerated and eclectic forms of free expression (especially sexual expression) to essentialize the divisions between the stultified East and the liberated West. In satirizing these adherents of "western aesthetics," Five Star Billionaire deters us from celebrating the literary or the aesthetic over and against the neoliberalism of Rising Asia.57 In the United States, efforts to justify the value of the arts within the neoliberal university have often portrayed humanist fields as "goldmines of anti-determinist thinking."58 What fascinates me about Five Star Billionaire is that it actually caricatures the Western "artistic temperament" while nuancing the conventionality of Chinese desiring subjects. While Aw subtly lampoons the self-righteousness of the Asian Anglophile who totes around Western Aesthetics, he is far gentler in its treatment of the five Malaysian Chinese migrants, the star-crossed characters whose intersecting storylines are powered by brutal social determinism and overweening fatalism.

The subject of particular generic interest is Phoebe, who pursues wealth, class, and ethnic authenticity through determined and sincere imitations of conventionality. In using Phoebe to destigmatize self-help — a genre premised on the generic — Aw forces a reexamination of world literature's worldliness. That is to say, Aw subjects aesthetic education to critique from the position of self-help education. This critique not only puts pressure on colonial mimicry's object of desire. It also places the knockoff girl (rather than the mimic man) in a privileged position of historical insight because of her proximity to the generic. From Phoebe's journal entries we learn that reading, like all forms of consumption, is most valuable when it is most instrumental. Although Walter's Secrets of A Five Star Billionaire is one of her favorite books, she plumbs it not for its autobiographical story but for its useful aphorisms. She seeks cultural enrichment not for the sake of enlightenment but for the specific purpose of financial gain. In this respect, Phoebe's romantic relationship to Walter is functionally identical with her readerly relationship to him:

She would use Walter for as long as she could . . . She would not only enjoy the fine dinners but also use the opportunity to learn about the Western countries he had visited. She would listen carefully to his stories about getting lost in Rome and his description of the view from the Eiffel Tower, and she would store them away for use one day, when she was at dinner with someone else, her true soul mate. She would accept all his offers of evenings at the opera and ballet; she would use him to make herself better. Make use of men as they would make use of you (225).

Reading Walter is supplemented by dating Walter. From this relationship, Phoebe seeks neither knowledge nor love. She merely wants the rapid-fire education that Walter can provide in abridged form. Like C.S. the aesthete, Phoebe knows the value of high culture, whether the knock-off or the real thing. And like Western-educated university graduates who pontificate on art and philosophy, Phoebe attempts to operationalize her cultural education, for example by singing Édith Piaf's "La Vie en Rose" or by "twirl[ing] her torso in the way she imagined Spanish dancers might" (229-30, 371). Is one mode of knowledge production more imitative or less legitimate than the other? In Five Star Billionaire, mimic men and copycats coexist. In fact, their cognate desires bear out the overlapping vectors of imperial power in the novel: a long-ingrained colonial legacy of humanistic education, especially in former colonies such as British Malaya; a late-twentieth-century neocolonial regime of the global creative economy steered by the United States; and a potential hegemonic shift to China, which dominates in the global manufacturing of brand name goods and counterfeits. In the world that these vectors of power co-produce, mimic men such as C.S. symbolize the staleness and short-sightedness of an Old World culture while knockoff girls such as Phoebe attune us to the changing relation between economic and cultural power during the seasonal ambiguity of America's autumn and China's spring.

In response to a question about Five Star Billionaire's "focus on the perils of Asian capitalism," Aw has remarked, "It's strange, but I really don't see my representation of Asian capitalism as negative, which is very different from how most people have read it, particularly in the West."59 Whether one interprets Aw's novel as a critique of a still-Eurocentric literary world-system or an exposé of Global China as "capitalism on crack," it's clear that empire has more than one cultural referent.60 In reading Five Star Billionaire alongside other depictions of Global China, I have suggested that Chineseness has come to function a bit like Susan Koshy's conceptualization of hegemonic whiteness — that is, like a racial and ideological category that derives power from flexibility. As Koshy explains, "whiteness as culture" now evokes among some "minorities and immigrants" negative traits such as "decadent, sexually promiscuous, hav[ing]weak family ties, et cetera." By contrast, what Koshy terms "whiteness as power" operates through opportunistic "affiliations between whites and nonwhites" depending on circumstance.61 Chineseness, when transformed from a genetic trait into a generic template, bears out a similar kind of affiliative and incorporative tendency. Hence, although it is more common to view the genealogical component of genre as "a way of locking individuals and groups into . . . a determination that is immutable and intangible in origin," the replacement of genealogical origins with generic conventions might introduce more elastic modes of imperial governmentality.62

The promises and perils of an emergent non-Western imperial formation remain beyond our total comprehension. In light of this uncertainty, I have, like many critics, found genre — its drag, drift, wane, dispersal, and impasse — a valuable measure of history's slippery presentness.63 Understanding the uncertain present as a consequence of empire's still unrecognizable forms requires us to take seriously the relation between genre and genealogy as exploited by long-distance nationalisms and roots-oriented diasporas. Thinking historically about empire might thus begin with treating Global China as a paradoxical genre: one that is both loosely diasporic and rigidly conventional; flexibly hegemonic and sub-sub derivative. These paradoxes make Chinese femininity an especially crucial analytic for examining empire on the move. A desiring subject's inhabitation of the generic, it turns out, can yield provisional hypotheses about empire's new thresholds and proprietary models. On a more grounded day-to-day level, such a subject can also provide glimpses of empire's normalized forms, social pathologies, and mundane comforts. Might this desiring subject, I wonder, also be the source of empire's hibernating politics?64

Sunny Xiang is an assistant professor of English at Yale University. She's currently completing a book manuscript that uses weak tones and flat affects to rethink Asian self-representation during the long cold war.

References

I'm deeply grateful to Andy Chih-ming Wang for repeatedly pushing me to address the Malaysian Chinese dimension of Five Star Billionaire. His enthusiasm and support for an early version of this essay helped me persevere with it. Sustained conversations with Cheryl Naruse were formative to my thinking about far too many topics to adequately list. Thanks to Yale's Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Colloquium for their perceptive feedback on an early draft of this essay. Sarah Chihaya, Kinohi Nishikawa, and Josh Kotin were an indomitable editorial team — I've learned much from the chance to think alongside them.

- Kevin Kwan, Crazy Rich Asians (New York: Anchor Books, 2013), 3-12. [⤒]

- Rebecca Walkowitz, Born Translated: The Contemporary Novel in an Age of World Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), 29.[⤒]

- Gayatri Spivak, Other Asias (Maldon: Blackwell Publishing, 2008), 219.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Eric Hayot, The Hypothetical Mandarin: Sympathy, Modernity, and Chinese Pain (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 21-22.[⤒]

- On how the novel of manners provides "something like a thin chronotope" for historicizing the present, see Theodore Martin, Contemporary Drift: Genre, Historicism, and the Problem of the Present (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 36.[⤒]

- Lauren Berlant, The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture(Durham: Duke University Press, 2008), 27.[⤒]

- Shu-mei Shih, Visuality and Identity: Sinophone Articulations across the Pacific (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 33.[⤒]

- For a critique of how Asian Americanist scholars have neglected to take seriously "intergenerational conflict," see the introduction to erin Khuê Ninh, Ingratitude: The Debt-Bound Daughter in Asian American Literature (New York: NYU Press, 2005). Although Ninh is writing within the critical tradition of Asian American literary studies, the autobiographical fictions she examines are narrated by Chinese daughters located in North America.[⤒]

- Tash Aw, Five Star Billionaire (Random House, 2013).[⤒]

- Hayot, The Hypothetical Mandarin, 9, 15.[⤒]

- Overseas Chinese or huaqiao refers to the Chinese diaspora, especially in Southeast Asia. Historically, the huaqiao (translated literally as "Chinese bridge") have been viewed as mediators between Mainland China and outside investors. Despite political tensions between Mainland China and Taiwan and Hong Kong in particular, the vision of a "Greater China" emerged in the 1990s to describe the increasing economic integration of diasporic Chinese businesses. See Aihwa Ong, "Chinese Modernities: Narratives of Nation and of Capitalism," in Ungrounded Empires: The Cultural Politics of Modern Chinese Transnationalism, eds. Ong and Donald M. Nonini (New York: Routledge, 1997): 177-202. [⤒]

- Franco Moretti, Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for Literary History (London: Verso, 2005), 14, 17-18. Joseph North's Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017), critiques the trope of the pendulum for history's movement. For him, a pendular motion that suggests "a conceptual impasse: one wants to go forward, but one does not yet know how to do so, except by going back" (142). [⤒]

- Giovanni Arrighi, Adam Smith in Beijing: Lineages of the Twenty-First Century (London: Verso, 2007), 178. For more on "the sign of autumn," see Arrighi, The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times (London: Verso, 1994).[⤒]

- Jed Esty, "Realism Wars," NOVEL 49, no. 2 (August 2016): 317. Joe Cleary examines how monumental theories of realism by Georg Lukács, Erich Auerbach, and Mikhail Bakhtin grew out of European and world crisis; see "Realism after Modernism and the Literary World-System," Modern Language Quarterly 73, no. 3 (September 2012): 255-68.[⤒]

- Ibid., 318.[⤒]

- Joseph Slaughter, "World Literature as Property," Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics, no. 34 (2014): 39-73.[⤒]

- An account of the self-help novel in relation to "Rise of Asia" discourse that has influenced my thinking is Colleen Lye, "Unmarked Character and the "Rise of Asia": Ed Park's Personal Days," Verge: Studies in Global Asias 1, no.1 (Spring 2015): 230-254.[⤒]

- Wai Chee Dimock, Deep Time: American Literature and World History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 80; Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism (Durham, Duke University Press, 2011), 210. Berlant usefully characterizes this synonymy as such: "femininity is a genre with deep affinities to the genres associated with femininity" (3).[⤒]

- Dimock, Deep Time, 91.[⤒]

- E.K. Tan, Rethinking Chineseness: Translational Sinophone Identities in the Nanyang Literary World (Amherst: Cambria Press, 2013), 94-95, 7. [⤒]

- Dimock, Deep Time, 78.[⤒]

- Lisa Rofel, Desiring China: Experiments in Neoliberalism, Sexuality, and Public Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), 20.[⤒]

- Laikwan Pang, Creativity and its Discontents: China's Creative Industries and Intellectual Property Rights Offenses (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 201.[⤒]

- According to Mark Rose, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century discussions of literary property frequently drew an analogy between a literary work and a landed estate. This analogy helped make the case for an author's natural right to perpetual copyright, to full and permanent ownership of the metaphorical "fruits" produced by his mind rather than the material manuscript. See Authors and Owners: The Invention of Copyright (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), 56-58.[⤒]

- Peter Ganea and Thomas Pattloch, Intellectual Property Law in China (Kluwer Law International, 2005), xii.[⤒]

- See chapter 2 of William P. Alford, To Steal a Book is an Elegant Offense: Intellectual Property Law in Chinese Civilization (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1995). [⤒]

- Martin Dimitrov, Piracy and the State: The Politics of Intellectual Property Rights in China (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 4.[⤒]

- Aihwa Ong, Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999).[⤒]

- Leigh Claire La Berge, Scandals and Abstraction: Financial Fiction of the Long 1980s (Oxford, 2014), 117. [⤒]

- Although Tina Chen is writing about Asian Americans rather than Chinese nationals, her description of "stereotypes of Asians as 'sneaky,' 'secretive,' and 'inscrutable'" is instructive for my understanding of Oriental imposture. Chen writes, "Such characterizations coalesce into the figure of the Asian American as spy or alien, a figure whose foreign allegiances make it not only possible but probable that his/her claims to American-ness are suspect or, in other words, impostured." See Double Agency: Acts of Impersonation in Asian American Literature and Culture (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2005), xviii.[⤒]

- Ong, Flexible Citizenship, 135.[⤒]

- Ibid., 144-45. Employing another kind of familial trope, Arrighi describes the Chinese diasporic capital as the "matchmaker" that enabled the conjugal bonding of "foreign capital and Chinese labor, entrepreneurs, and government officials" (Arrighi, Adam Smith, 351).[⤒]

- On the root model of Chinese diaspora, see Tu Weiming, The Living Tree: The Changing Meaning of Being Chinese Today (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1994); L. Ling-chi Wang, "Roots and Changing Identity of the Chinese in the United States," Daedalus 120, no. 2 (Spring 1991): 181-206. Adapting Edward Young's organic metaphor in Conjectures on Original Composition, Martha Woodmansee writes, "Original works . . . are vital, growing spontaneously from a root, and by implication, unfold their original form from within"; see The Author, Art, and the Market: Rereading the History of Aesthetics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 54.[⤒]

- La Berge, Scandals and Abstraction, 75.[⤒]

- Ibid., 96.[⤒]

- Berlant, Female Complaint, 120.[⤒]

- Amy Chua, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother (New York: Penguin, 2011), 30.[⤒]

- Ibid., 56.[⤒]

- Ibid., 4.[⤒]

- Yi Shun Lai, Not a Self-Help Book: The Misadventures of Marty Wu (New York: Shade Mountain Press, 2016), Kindle edition, location 325.[⤒]

- Wenche Ommundsen, "From China with Love: Chick Lit and the New Crossover Fiction," in China Fictions/English Language: Essays in Diaspora, Memory, Story, ed. A. Robert Lee (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2008), 327.[⤒]

- Quoted in ibid., 328. [⤒]

- Linda Williams, "Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess," Film Quarterly 44, no. 4 (Summer 1991), 4.[⤒]

- Caroline J. Smith, Cosmopolitan Culture and Consumerism in Chick Lit (New York: Routledge, 2007), 11.[⤒]

- Pamela Thoma, "Romancing the Self and Negotiating Consumer Citizenship in Asian American Labor Lit," Contemporary Women's Writing 8, no. 1 (March 2014): 20.[⤒]

- Berlant, Female Complaint, 210.[⤒]

- For example, the Chinese American narrator Candace Chen in Ling Ma's Severance (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018) offers the follow anatomy of the Louis Vuitton bag when visiting Hong Kong: "You could buy the actual bag, a prototype of the actual bag from the factory that produced it, or an imitation. And if an imitation, what kind of imitation? An expensive, detailed, hand-worked imitation, a cheap imitation made of polyurethane, or something in between?" (100). In The People's Republic of Desire (New York: HarperCollins, 2006), Annie Wang writes, "Faking one's birthplace is the quickest way to diminish the discrepancy between classes." A fake biographical origin "serves its purpose as conveniently as a fake Chanel bag" (5). A related message appears in Kwan's Crazy Rich Asians, where the knockoff Goyard handbag becomes a sign of the waning differentiation between "fakes" and "real fakes" — not only between handbags but also between nouveau riche Mainland climbers and old money Singaporean Chinese (223).[⤒]

- Randy Martin, Financialization Of Daily Life (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002), 98-99. Martin is referring to the tendency for self-help to address how to purge the self of forms of excess — for instance, excess weight or excess substances.[⤒]

- Sara Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 10.[⤒]

- Maya Jaggi, "Tash Aw: A Life in Writing," The Guardian, March 15, 2013.[⤒]

- Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan, Sarong Party Girls (New York: HarperCollins, 2016), 28[⤒]

- Rofel, Desiring China; Rofel, Other Modernities: Gendered Yearnings in China after Socialism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999); Jing Wang, Brand New China: Advertising, Media, and Commercial Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008).[⤒]

- Rofel, Other Modernities, 31.[⤒]

- Wei Hui (Zhou Weihui), Shanghai Baby (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001), 12.[⤒]

- Pang, Creativity and Its Discontents, 185.[⤒]

- Two essays that have used self-help novels to mine the critical potential of the aesthetic include Weihsin Gui, "Tactical Objectivism: Recognizing the Object within the Subjective Logic of Neoliberalism in the Fiction of Tash Aw and Lydia Kwa," Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory 25, no. 4 (2014): 291-311; Angelia Poon, "Helping the Novel: Neoliberalism, Self-Help, and the Narrating of the Self in Mohsin Hamid's How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia," The Journal of Commonwealth Literature 51, no. 1 (May 2015): 139-150.[⤒]

- Christopher Newfield, Unmaking the Public University: The Forty-year Assault on the Middle Class (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 144.[⤒]

- Justin McDonnell, "Interview: 'Five Star' Novelist Tash Aw Explores Human Side of New Asian Dream," Asia Society, August 29, 2013.[⤒]

- Nina Martyris, "Gatsby over Gandhi: The Asian Jazz Age," The Missouri Review 37, no. 2 (2014), 173.[⤒]

- Susan Koshy, "Morphing Race into Ethnicity: Asian Americans and Critical Transformations of Whiteness," Boundary 2, 28, no. 1 (2001), 186. The role of the knockoff in thinking Global China as an imperial formation downplays (but does not disavow) the alternate artistic avenues and political critique afforded by counterfeit culture and piracy aesthetics. On the political potential of counterfeit culture, or shanzai culture, in contemporary China, see Fan Yang's Faked in China: Nation Branding, Counterfeit Culture, and Globalization (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2015). For a more politically redemptive reading of the derivative in Aw's novel, see Lily Cho, "Fakes, Counterfeits, and Derivatives in Tash Aw's Five Star Billionaire," ARIEL, 49, no.4 (October 2018): 53-75.[⤒]

- Rey Chow, The Protestant Ethnic and the Spirit of Capitalism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 120.[⤒]

- For Fredric Jameson, genre's privileged relation to historical materialism rests with its elucidation of social constraints. Influenced by yet departing from Jameson, critics such as Berlant, Dimock, La Berge, and Martin associate the usefulness of genre not with its representativeness but its elusiveness.[⤒]

- For one account of self-help's potential for mobilizing and politicizing readers, see Beth Blum, "The Self-Help Hermeneutic: Its Global History and Literary Future," PMLA, 135, no.5 (October 2018): 1099-1117.[⤒]