Global Horror

In 2019, black children are still denied consideration as children. Anti-black violence has never spared and continues not to spare children. Children are neither symbolic exceptions nor accidental casualties but key targets of racist violence. If we consider the enslaved child not as an outlier but as a central victim of racial oppression, we can better understand the continued resonance of the figure of the carceral child in the twenty-first century.

In this short essay, I turn from past horrors in literary depictions of enslaved children to present horrors of incarcerated children. I present nineteenth-century discourses around the enslaved child in order to show that figure's centrality to discourses of racialized childhood in the United States. This centrality shows that 1) racist anxieties were pragmatically directed toward ensuring a future of white supremacy and that 2) antiracist arguments (and particularly those formed by formerly-enslaved black people) have historically considered childhood as real and experienced, beyond the simply symbolic resonances by which it is usually considered. The most prominent reverberation of the enslaved child in the U.S. (as with reverberations of slavery more generally) manifests itself in the policing of children and in childhood incarceration.1 As the carceral child becomes the echo of the enslaved child in popular discourse, we can see familiarly horrific constructions of childhood and its racial resonances. I make this comparison, in particular, to urge that our contemporary discussions of racist violence — which cannot avoid the fact of child victims of racism (in its various forms) — might reconsider the very real child of antislavery discourse as a useful touchstone for antiracist activism in the twenty-first century.

Institutions of anti-black violence and state-sanctioned terror elicit horror in their victims and those who care about them. Horror is an emotional response of fear and repugnance that serves as both a protective and an ethical reaction to racist oppression. Here I mean to connect horror as an experience of trauma to horror as an act of sympathetic recognition that trauma has occurred. To feel horror is not (necessarily) to experience surprise, but sometimes to dwell in the expectation of dread. Recognizing the particular horror of this confluence of racism and child abuse is to react empathetically and viscerally to these intersections of age and race that are not incidental to structures of oppression but fundamental to their construction and perpetuation. This history of black children's incarceration shares horrific similarities with other histories of child captivity, such as the forcible re-education of children in Indian boarding schools in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and the indefinite incarceration of immigrant children still held in detention centers at this present moment. I present the enslaved child and the carceral child as figures produced through anti-black violence in order to consider how the very category of childhood is constructed by and contributes to the consideration of what kinds of abuses do and do not produce horror for potential sympathizers with the victims of these abuses, whose horror is not vicarious but experiential.

The Enslaved Child

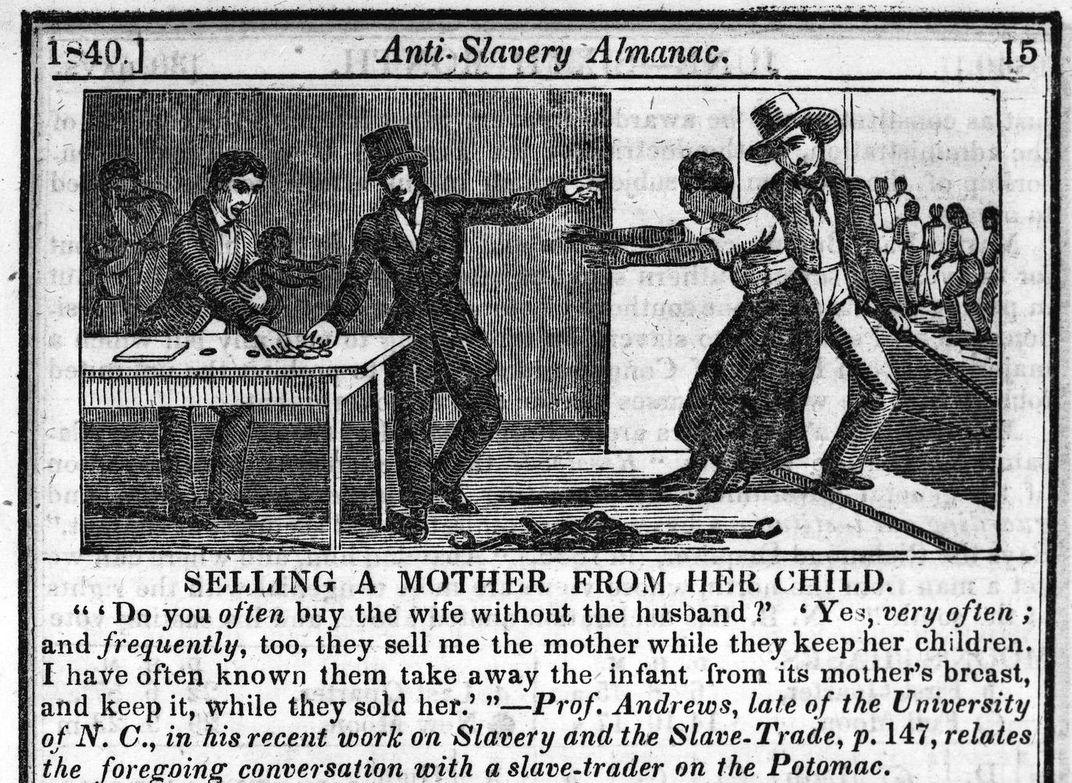

One of the most prominent recurring scenes of antebellum antislavery literature involves the separation of an enslaved mother and child. Such separations were not historically uncommon, as formerly enslaved writers such as Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, and Solomon Northup would explain that they had witnessed, been subjected to, or tormented by this particular form of violence. This theme would be repeated in slave narratives as well as in antislavery advocacy writing, fiction, and visual culture. One example of forced familial separation can be seen in an 1840 issue of the Anti-Slavery Almanac, a publication of the American Anti-Slavery Society, which bears an image and repeats a dialogue depicting the act of "Selling a Mother from her Child."

This scene, familiar among enslaved people and enslavers as well as with antislavery advocates, is one of horror, anti-black violence, and despair. The subjects of this scene — mother and child — experience racism as horrific trauma. Empathetic viewers experience vicarious horror in recognition of this scene's trauma — rather than as part of an inherently benevolent or racially justified institution. To truly consider such scenes of the forced separation of parents and children demands an emotional response of sympathetic horror, one that activists who repeated them hoped would lead to political action.

The sentimentality of such scenes sought to garner white sympathy for enslaved black people by reminding white people of their own families and their affective bonds with their most vulnerable members — children. The most popular antislavery text of the nineteenth century, Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, would include a plotline in which Eliza Harris, knowing that her enslaver was about to sell her son, Harry, away from her, flees to Canada. Eliza appears on the very doorstep of an Ohio Senator, Mr. Bird, who supports the Fugitive Slave Act, a controversial law that required citizens of free states to assist in the re-enslavement of self-emancipated people. Mr. Bird's wife deems this support of slavery unchristian, and thereby serves as the novel's model for white sympathy and its radical potential.

The Birds break the law to help Eliza and her child escape to Canada. This radical act hinges, though, on a rather moderate model of sympathy. They are able to imagine Eliza's pain because they imagine this light-skinned black woman as somehow like themselves. Their closest position of mutuality is that of parents and, particularly, parents who understand loss. Eliza herself makes this connection as she asks Mrs. Bird outright, "have you ever lost a child?"2 They have. Before Eliza leaves their home, they give her their dead son's clothes, imagining that they understand something about this mother's love for her child and desire to protect him. But they cannot understand the ever-present threat of violence against black individuals and black families with which enslaved black people were forced to contend.

Critics of the novel from the nineteenth century forward have acknowledged the problem inherent with Stowe's (and others') positioning of mixed-race black people as more likely recipients of white sympathy.3 The coupling of these characters' light skin with popular antislavery focus of the normative mother-and-child relationship reinforced notions of biological family relations as exceptional in their capacity for love and care, extending this to expectations for white sympathy: Mrs. and Mr. Bird are understood to care for Eliza and her son not in recognition of their own humanity or the inherent injustice of slavery, but only insomuch as they can compare them to their own family.

The trick of antislavery literature like Stowe's was that this move endeavored (most optimistically) to get people to care about black children like Henry, even if they did not care enough about black adults to oppose their enslavement. As antislavery discourse highlighted this scene, it focused on the particular violence and trauma perpetuated on enslaved children, who (even more than enslaved adults) were presented as innocent victims undeserving of this cruel treatment. This move (just as much as Stowe's centering of the death of Eva St. Clare, the white daughter of enslavers, in her novel) utilized popular constructions of idealized childhood whiteness and innocence.4

Even as books like Stowe's coupled notions of childhood vulnerability and innocence, many white people — even declared abolitionists — refused to afford black children the same vulnerability, innocence, and humanity that they granted white children. Alongside this image of a black child under threat, Stowe herself would paint a different image of black childhood, and one that would become more iconic than that of Eliza's son: Topsy.

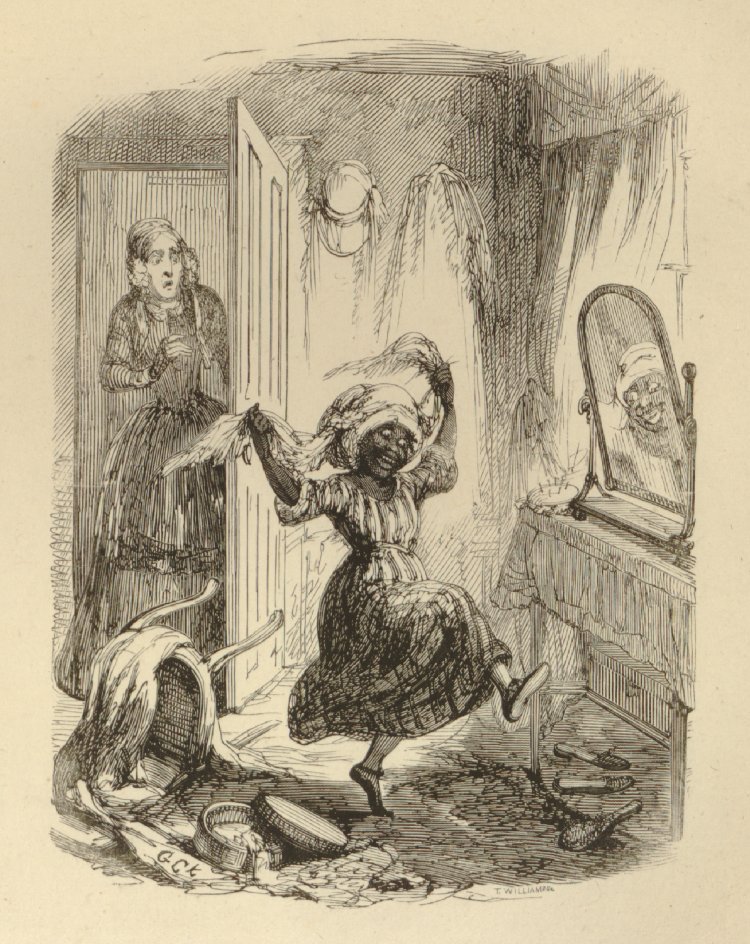

Unlike Eliza's light-skinned son Harry, Topsy would become a more visible and more obviously horrific figure of black childhood. Topsy and her image would circulate in the popular culture explosion that would accompany Uncle Tom's Cabin and extend well beyond Stowe's novel. Topsy appeared in blackface minstrel theater, song, material culture, picture books, advertisements, and film, and resembled similarly stereotyped images of black children well into the twentieth century.

Topsy's most dangerous effect is that her stereotypical iconicity stands in for other examples of black children. She represents the image of the enslaved child even more so than the most prominent historical figure of U.S. slavery, Frederick Douglass. He was only twenty years old at the time of his self-emancipation, making his 1845 autobiographical narrative overwhelmingly an account of enslaved childhood. Topsy is not exceptional, however, but reflective of the preponderance of popular, white supremacist associations of black children with bad behavior. Today, continued stereotypical associations of black children with bad behavior mask disparities in the punishment of nonwhite children for similar behaviors and rationalize the structural oppression of black children by virtue of their imagined lack of innocence.

Enslaved childhood would ultimately be widely framed as an egregious horror in both efforts to prioritize white children and protect them even from knowledge of slavery's worst horrors and efforts to protect and humanize nonwhite children. As the enslaved child was thus constructed — vulnerable, oppressed, and alternately sympathetic and wicked — she became an orienting vehicle for discourses of childhood in the United States and also for those of African American freedom and captivity, more broadly.

The Carceral Child

Hypervisible images of "bad" black children like Topsy contribute to their disparagement and criminalization. Associations of white childhood with innocence — and by extension, nonwhite childhood with supposed guilt — would continue to dominate popular notions of childhood until our present moment. As a result of these associations, childhood would be at the center of discussions of freedom. Prior to federal emancipation, the gradual emancipation laws of northern states tended to free children before (or in lieu of) their adult counterparts. This age-tiered form of emancipation implied that children were either more deserving of freedom or more safely emancipated than their adult counterparts This picture of emancipation also produced a misleading narrative of liberatory progress. Although emancipated children would be poised toward a future in which slavery would fade out of living memory, children would be among the victims of later structures for black captivity.

Ultimately, racist questions of black people's right to freedom would shift from accusations of innate inferiority to accusations of culpability and desert. Following emancipation, white supremacists no longer needed pretend that black people required captivity according to natural law and for their own benefit, but instead argued that they deserved incarceration for a series of invented and disproportionately punishable offences. Despite their prominence, questions of innocence and guilt are red herrings in debates about human rights and oppression. Such questions persist only insomuch as they suggest an insidious form of victim-blaming. Notions of children as "innocent victims" produces a seeming redundancy that actually qualifies victimhood by deceptively suggesting that some victims are not innocent but deserving of abuse.

White racist imaginings of black people as perpetual children contributed to the various ways that legal freedom did not lead directly to equal citizenship. This figural employment of childhood evacuated the notions of innocence with which white childhood would be imbued. This metaphorization of childhood reveals childhood's racialized construction. As Colin Dayan writes, "Bad logic makes good racism."5 Whether metaphorical or actual, black childhood would not be granted the qualities that were seemingly inherent to white childhood. Moreover, these constructed and metaphorical meanings attached to childhood are eclipsed by the histories of actual black children, whose experiences would illustrate children's removal from the categories of innocence and protection with which childhood would be associated.

The enslaved child is a figure that thereby portends the ugly exception that would be built into the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which would allow "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime." This last clause, of course, allowed for the easy transition from chattel slavery to mass incarceration as a locus for anti-black oppression. Children's capacity for incarceration would not be absented from the Thirteenth Amendment's exception. The convict lease system would become one part of the transition from national narratives describing black captivity as natural to narratives describing it as punitive. This and other forms of incarceration would also include black children who, even following emancipation, would be held captive and even forced into labor in the service of a white supremacist system of capital.

The carceral child, then, is a figure not only of children's imagined potential, but sometimes their present reality. Children encounter prisons not only through the incarceration of their parents or the trajectory of the school-to-prison pipeline that funnels children from certain schools into a system of mass incarceration once they reach adulthood, but via their own carceral experiences.

The juvenile prison is one site that produces the carceral child. Austin Reed, author of the first known African-American prison narrative, began his incarceration in a children's prison in 1833. Reed writes that he is "just a boy" (he is no more than ten or eleven years old) when he learns that "I was goin' to be taken from my mother and be sent off to the House of Refuge in the city of New York . . . until I was one and twenty."6 Reed was sentenced for the remainder of his childhood for an act of arson, committed against a family to whom he had been indentured. He committed this crime in retaliation for abuse, recalling "the barn where I was tied up like a slave and thrash by the rough hand of a farmer who had no business nor no right nor authority to lay a hand on me."7 As an adult, Reed would be reincarcerated at Auburn State Prison, but his formation as a "Haunted Convict" began in childhood.

By incarcerating children, the state defines some forms of childhood outside the realm of idealized 'innocence." These children, it holds, are framed instead by guilt. Incarcerated children are defined out of childhood itself when tried as adults or sentenced into the age of majority. Unsurprisingly, black children are more likely to be thus defined outside of childhood than their white peers, as children's prisons in the twenty-first century United States — reflecting mass incarceration in the nation more generally — disproportionately hold nonwhite people. According to data from the Department of Justice, "Despite long-term declines in youth incarceration, the disparity at which black and white youth are held in juvenile facilities has grown. As of 2015, African American youth were five times as likely as white youth to be detained or committed to youth facilities." In some states, black children were ten times more likely than white children to be imprisoned. The racially disparate policing of childhood thereby frames certain children as children and others as criminals, evacuating the supposition of innocence or culpability afforded to other people of the same age. Notions of childhood innocence would not supplant urges to frame black children as culpable beyond their white peers. And the particular vulnerability of children would render them even easier targets for abuse, perhaps, than adults.

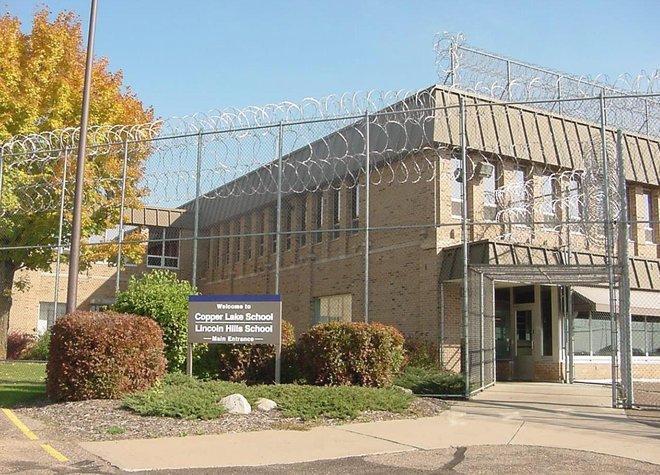

In the summer of 2015, I visited a prison for children, on a tour of the state of Wisconsin with other faculty from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. It was not the first prison I had visited, but it was the first children's prison I had seen. It was horrific (though not everyone around me seemed to detect the horrors). This prison is often referred to by the names of its (gender segregated) Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake "Schools," a euphemism masking the fact of child incarceration. Ironically, although the term "school" emphasizes childhood rather than imprisonment, some of the children held there have been tried and sentenced as adults. The state of Wisconsin is one of the worst for racial disparities in incarceration rates, and this disparity extends to the juvenile prison system. In 2016, although black children between 10 and 16 years old comprised only ten percent of the state's youth population, they constitute 47% of the state's incarcerated children. In the visiting room, there was a "diversity" mural. Several buildings were named after famous black people, such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman.

About a year after our visit, allegations against the facility and its employees surfaced. They included abuse, sexual assault, and child neglect. A 16-year old child had his arm broken by guards, who then denied him any medical treatment for hours, sent him to see a doctor only a week later, and failed to notify his mother about the injury. Another 16-year-old child was severely brain-damaged after trying to hang herself in her cell. She had not been monitored according to protocol after expressing suicidal thoughts. A federal court ordered guards to reduce the use of pepper-spray against the children and to reduce their use of solitary confinement, allowing the children at least two hours per day out of their cells.

During my visit I asked every prison employee I encountered how many hours per day the children were confined to cells. No one could or would answer me. I was chastised for questioning people who were "just doing their jobs." We visitors were allowed to speak to a few incarcerated children, though it is unlikely that their parents or guardians had given permission for their children to interact with us, adult strangers. I saw no obviously black staff members while I was there and was told that the "foster grandparents" program included only white volunteers. Many of these children were incarcerated far from their homes and families and communities and it was clear, too, what efforts had been made to remove them from notions of childhood itself. Although the prison was set to close in 2021, that closing has apparently been delayed.

The Beloved Child

Black children of black parents are especially vulnerable, as anti-black racism works not only via structures that affect individual people, but generations. In her discussion of the centrality of Black motherhood to U.S. discourses on reproductive freedom, Dorothy Roberts notes also the ways in which black reproduction itself has been policed. The crux of this policing, Roberts shows, is the continued framing of black people as responsible for their own systemic oppression.8 This criminalization of black parents is part of the longer history of white supremacist attacks on black families. In this way, the enslaved child and the carceral child are produced in bizarre isolation, imagined and foisted not only outside of childhood but outside of family.

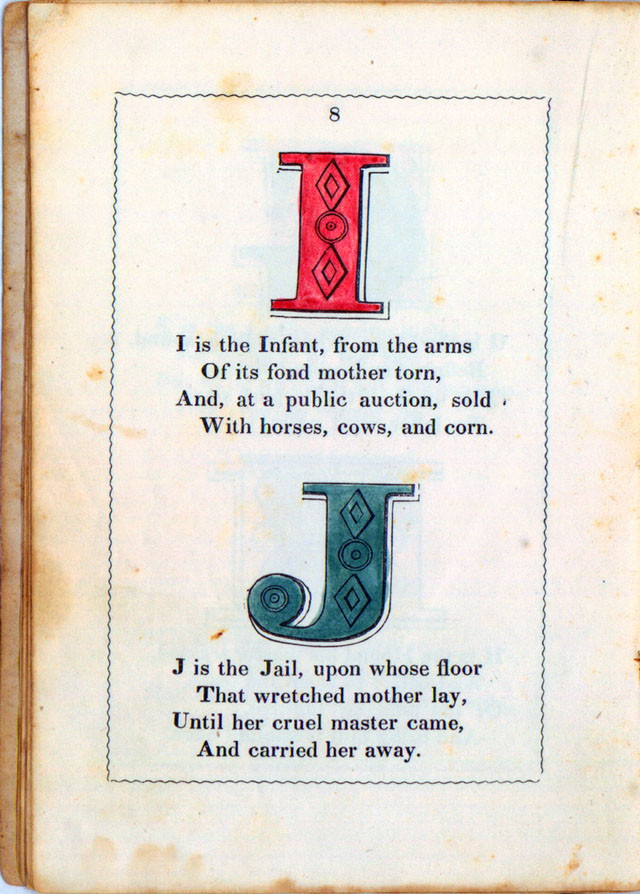

The Anti-Slavery Alphabet's pairing of the "Infant, from the arms / Of its fond mother torn" and the "Jail, upon whose floor / That wretched mother lay" recognizes the child's isolation by again staging the moment of mother-child separation. The poem recognizes the enslaved child's salability but misses their captivity beyond this moment. Still, the juxtaposition of Infant and Jail suggests the child's experience within systems of anti-black violence that extend beyond the specificity of slavery. The image of the black child separated from their mother would follow a trajectory of historically-contextualized horrors from enslaved separations to juvenile incarceration.

The enslaved/carceral child who has been separated from their parents reflects some black people's experiences and the historical workings of systemic racist violence. But this horrific image also masks forms of black family, love, and care for children. Constructions of the carceral/enslaved child imagine them outside the realm of black community and care, supposing that black children require white intervention rather than an end to anti-black racism and the dismantling of white supremacist structures. In a somewhat uncharacteristic moment, Stowe describes Topsy quite accurately, as "a neglected, abused child." Her young body bears the marks of physical abuse, but her new enslaver is more concerned that she has been deprived of a Christian education. Moreover, the child has no memory or concept of family. When asked "Who was your mother?" she explains that she "never had no father nor mother, nor nothin'. I was raised by a speculator, with lots of others. Old Aunt Sue used to take car on us."9 We never hear mention of what care "Aunt Sue" took of Topsy and the enslaved people in the St. Clare home are oddly uninterested in caring for the child.

Denying what black feminist scholar Carol Stack has called "fictive kinship" ties often formed by enslaved people, Topsy has no black kin, biological or otherwise, in Stowe's novel.10 Framed as an inherently "motherless" child, she is thereby positioned as a candidate for the kind of white saviordom for which much of white antislavery writing and action would be critiqued. Topsy would change her demeanor from wicked to good as a result of the good Eva's friendship and love and the white, northern Ophelia's Christian education and domestic training. The reasons the enslaved black people in Stowe's novel refuse to care for Topsy are grounded in their shared assessment of her wickedness, but also imply racist myths denigrating black parents that would become increasingly popular in the twentieth century. Thus, the blame for Topsy's neglect is bizarrely shifted from white enslavers to a black enslaved community who similarly devalue a black child who is unable or unwilling to conform to white standards of beauty and behavior.

As it turns out, however, some people have always recognized black children (like black people, more generally) as deserving of love and care. Historian of slavery and childhood Wilma King acknowledges that enslaved children's experiences of childhood were likely facilitated by the enslaved black people who cared for them, sometimes in the absence of biological kinship relations.11 Nazera Sadiq Wright similarly demonstrates that, even while victimized and denigrated by white supremacist society and popular culture, black girls have been empowered within their own communities, historically.12 In The Brownie's Book, the first periodical produced entirely for African American children, editor W.E.B. Du Bois would provide image after image of black children who were celebrated and loved even beyond their families and communities as these images of "Our Little Friends" were circulated. To those for whom black children's lives have always mattered, black childhood has never been reduced to the enslaved or the carceral; it has eschewed both the idealized and the iconic in favor of the complex lives and relationships of actual black children. Still, people who care deeply about black children have been haunted by the knowledge that black children have not been accidental casualties but deliberate targets of anti-black violence. The preservation and protection of black childhood and black children has therefore been essential not only to the perpetuation of black futures, but for black life.

References

- For more on these connections see, for example, Erica Meiners, "Child's Play: Schools, Not Jails" in Child Slavery before and after Emancipation: An Argument for Child-Centered Slavery Studies. Ed. Anna Mae Duane (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017): 103-122.[⤒]

- Harriet Beecher Stowe, "In which it Appears that a Senator is But a Man," in Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1852),[⤒]

- Literary critics who have noted this problem include Sterling Brown, Carolyn L. Karcher, Werner Sollors, and Eve Allegra Raimon.[⤒]

- Robin Bernstein, Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights (New York: New York University Press, 2011).[⤒]

- Colin Dayan, The Law is a White Dog: How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake Persons (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013), 118. [⤒]

- Austin Reed, The Life and Adventures of a Haunted Convict, or the Inmate of a Gloomy Prison, With the Mysteries and Miseries of the New York House of Reffuge [sic] and Auburn Prison Unmasked [c.1858], Ed. Caleb Smith (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 20.[⤒]

- Ibid., 18.[⤒]

- Dorothy Roberts, Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty (New York: Pantheon Books, 1997), 5.[⤒]

- Stowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin, Chapter 10, "Topsy." [⤒]

- Carol Stack, All Our Kin: Strategies for Survival in a Black Community (New York: Harper and Row, 1974).[⤒]

- Wilma King, Stolen Childhood: Slave Youth in Nineteenth-Century American (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011).[⤒]

- Nazera Sadiq Wright, Black Girlhood in the Nineteenth-Century (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2016).[⤒]