Issue 2: How To Be Now

What follows is a story about the fate of the avant-garde in an age of its supposed demise. You'll likely be familiar with this story. Perhaps you've seen its specific events unfold, tracked its twists and turns, watched its players rise and fall. Or maybe you will recognize this story because it follows a pattern you have seen in similar stories.

Or perhaps you are in the midst of a story like this one now: You have circulated a petition or have instigated an institutional process that will result in someone's termination. You have been terminated. Your inbox is full of threats. Your Twitter feed is blowing up. You have been misunderstood, fatally. You have been hurt, gravely. You have called someone out in the name of justice. Your conference has been cancelled. Your television series has been cancelled. You are finally being heard. You have won. You have lost. Your friends are now your enemies.

The story I tell here is a story about politics and a story about art. But it is not about art as a redemptive force in the face of the polluted political sphere. It is a story about how art understands itself as political, and how political assumptions manifest themselves in evaluations of art.

I am telling this story because I think it reveals good reasons to reexamine a concept that many have long believed to be dead: the avant-garde. The concept of the avant-garde, I will argue, can help us better parse the dynamics of the kind of story that we are all, in one way or another, looped into these days: as protagonists and antagonists, as spectators and participants, as callers and called out.

And that is true, I will argue, even if we are inclined to say, alongside many of the characters in this story, fuck the avant-garde.

The Almost-Death of the Avant-Garde

How did so many of us come to believe that the avant-garde was dead?

A critical attitude I call compromise aesthetics was responsible. Compromise aesthetics is the belief that recent literature is characterized by the happy reconciliation of artistic practices, tendencies, and styles that were once opposed, such as experimentation and tradition, difficulty and marketability, formal play and easy digestibility. This position is crystallized in the Norton anthology American Hybrid (2009), which showcases work that, as Cole Swensen argues in her introduction to the volume, pairs "traits associated with 'conventional' work, such as coherence, linearity, formal clarity, narrative, firm closure, symbolic resonance, and stable voice" with "those generally assumed of 'experimental' works, such as non-linearity, juxtaposition, rupture, fragmentation, immanence, multiple perspective, open form, and resistance to closure."1 Against the avant-garde's uncompromising ethos of radical oppositionality, compromise aesthetics draws from a liberal set of assumptions, placing individual creativity over collective identification (as when an author is praised for her boldness in straddling outdated formal divides); patient rationality over fiery passion (as when works are criticized as being immature if they are wedded to a given movement or school); and moderation over excess (as when writers are praised for a restrained and subtle employment of techniques that could otherwise be "too much").

It should therefore not be surprising that when it was time for them to try to kill the avant-garde, proponents of compromise aesthetics did the deed with the kind of antiseptic cleanliness that denies its own violence: not by knife, gun, or rope, but by neglect.

Picture this: the avant-garde lies on a bare cot in a windowless room, limbs like fragile twigs, eyes sunken, skin dry and cracked, waiting for someone to notice its absence. All the while, its former friends sit and reminisce together over beers at a local bar. They shake their heads, murmuring vaguely wistful remembrances.

Alan Shapiro swirls his bourbon lazily around in his glass. "Many of the arguments that beset poets of my generation have been thankfully superseded," he says.2

Johanna Drucker nods. "This fresh sensibility," she says, "[is] ill-served by the remnants of modernism's legacy of avant-garde terms."3

"Let's be frank," David St. John interjects, slamming his beer down on the table. "We are at a time in our poetry when the notion of the 'poetic school' is an anachronism, an archaic critical artifact of times long gone by."4

"Sclerotic and decrepit . . . doddering," mumbles Drucker, nodding.5

"Slogans are fine when it comes to mobilizing political energies. But in the poems we read and write . . . don't we look for something more respectful of the truth with all its jagged edges . . . ?" asks Shapiro.6

The avant-garde is fueled not by love, but by antagonism. Respect, conciliation, assimilation, moderation, hybridity, complicity — all of these values threaten the avant-garde with irrelevance. Without that antagonism, the avant-garde withers.

The Avant-Garde Populist

A strange mutation of avant-gardism did, however, survive the age of compromise aesthetics: conceptualist writing. A practice exemplified by the poet Kenneth Goldsmith, conceptualism is a practice of appropriating existing texts as poetry. Goldsmith's book, Day (2003), for instance, consists only of a transcription of an entire issue of the New York Times. His follow-up work, The Weather (2005), is a transcription of a year of weather reports. Dubbed "uncreative writing," in one of Goldsmith's signal essays, this appropriative gesture is drawn from much earlier work in visual art by figures from the 1960s "neo-avant-garde" such as Andy Warhol, who in turn based his methods on early twentieth-century Dadaism. Derivative, unoriginal, and self-consciously uncreative as it might have been, this intervention earned Goldsmith a range of recognitions throughout the 2000s, including being named the first Poet Laureate of the Museum of Modern Art.

In 2011, Goldsmith's work was brought to an entirely new audience when he was invited to read at the White House's "Evening of Poetry." He read from Traffic (2007), which is comprised entirely of a transcription of a single day's traffic reports as they were given on New York City's AM radio station, 1010 Wins. The reading began with a selection of canonical poems about transportation between Manhattan and Brooklyn: Walt Whitman's "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry," and selections from Hart Crane's "Brooklyn Bridge." After giving his audience a taste of these traditional works, Goldsmith read a short excerpt from Traffic in full character, shouting out traffic reports as if he were giving them in real time.

Here is his account of what happened:

When I began reading traffic reports they all got up and started screaming, and yelling, and applauding, and laughing! . . . Now, of course this was the most radical of the three because it was completely appropriated. . . . And here, senators and democratic party donors were actually loving it! It got a great round of applause. So I thought to myself, gee-whiz. Suddenly the avant-garde and the populist have met, it's very strange.7

Goldsmith's suggestion that avant-garde techniques could hold mass appeal — could produce screaming, and yelling, and applauding, and laughing — sounds consistent with compromise aesthetics insofar as it sees old polarizations — those between the avant-garde and the mainstream — as no longer necessary.

This apparent similarity makes sense. Both compromise aesthetics and Goldsmith's avant-garde populism emerge out of a moment in which making art in opposition to the market seems like an anachronism. The difference between compromise aesthetics and avant-garde populism is, we might think, as much tonal as it is substantive, as both share a belief in the digestibility and marketability of novelty.

But there is a crucial difference between compromise aesthetics and avant-garde populism. Compromise aesthetics neutralize the force of avant-gardist techniques, reducing them to mere devices in an ever-expanding stylistic toolkit. Avant-garde populism, on the other hand, continues to feed upon the avant-garde's power to provoke, to shock, to incite scandal. So while compromise aesthetics and avant-garde populism emerge out of the same foundational condition, their consequences are different.

Compromise aesthetics imagine that literary culture might look like a fully achieved liberal pluralism. The literary community imagined by compromise aesthetics has no room for dissent because dissent is unnecessary. Everyone coexists, borrowing tools from one another as they are useful.

Avant-garde populism, on the other hand, sees itself as seizing upon the immediate impulses of the crowd, gathering around itself a frenzied energy that overrides individual preferences, interests, and internal dissent. Do you prefer Whitman over Crane? Perhaps. But the sheer shock and pleasure of hearing traffic reports read as poetry will make you forget that position.

This distinction might explain why Goldsmith doesn't use the world popular. Instead he says populist. Which seems like a small difference, except when one looks closely at his description of the White House reading.

Senators and democratic party donors were actually loving it! They all got up and started screaming, and yelling and applauding, and laughing!

Five years later, there would be another outsider to Washington who would similarly reflect on one of his first major appearances in DC:

People loved it. They loved it. They gave me a standing ovation for a long period of time. They never even sat down, most of them, during the speech.8

The Demagogue

Demagogues, explains Michael Signer, are "a phenomenon endemic to democracy itself" and yet they are also "the most central danger to democracy."9 This is because the demagogue, or "leader of the demos," can only exist in a situation where the demos is in power. But by harnessing the desires of the people toward a challenge to the existing order of the state, the demagogue also constitutes a threat to democracy, reliant as it is upon the strength of its institutions.

The demagogue highlights the tensions between democracy and liberalism in a liberal democracy. The existence of the demagogue may be a democratic phenomenon, but demagoguery tends to rest on a rejection of liberal values, mobilizing crowds rather than valorizing the individual, governing through passion rather than reason, polarizing rather than negotiating.

As Signer explains it, the political engine of demagoguery is populism; it "depends on a powerful, visceral connection with the people that dramatically transcends ordinary political popularity." But that popularity is achieved not by following norms, but by breaking them: demagogues "threaten or outright break established rules of conduct." And this rule breaking is not just window dressing. In their commitment to breaking the rules, Signer argues, demagogues "are intrinsically violent."10

Avant-garde populism is also defined by the pairing of rule breaking and popularity. The difference, of course, is that political demagogues mobilize actual political violence, whereas the provocations of avant-garde populists remain in the domain of art.

But that does not mean that avant-garde populism can be comfortably disentangled from the historical legacy of demagogic violence.

The avant-garde is defined, according to its most often cited theorist, Peter Bürger, by the effort to merge art and life in such a way that art might forcefully change reality.11 The result of this effort, however, as Maggie Nelson observes, is the tendency for avant-gardists to embrace violence. "Precision, transgression, purgation, productive unease, abjectness, radical exposure, uncanniness, unnerving frankness, acknowledged sadism and masoschism, a sense of clearing or clarity" — these are all strategies that, as Nelson notes, are hallmarks of the avant-garde along with the "excitements and effects" of "pure cruelty" that are imagined by figures such as Antonin Artaud.12

For this reason, it shouldn't be surprising that Goldsmith, too, eventually embraces violent subject matter. This begins with the publication of his Seven American Deaths and Disasters (2013), a transcript of 911 calls and media reports that immediately follow major American crises including the Kennedy assassinations, the death of Michael Jackson, and the Columbine shooting. It is a work that even Stephen Colbert has a hard time stomaching, calling it "vampiric" and asking the poet, who appears on his show in a garish pink suit, "Are you giving us a feast of other peoples' blood?"13

Sueyeun Juliette Lee observes that the works in Seven American Deaths and Disaster are "'easy' to read in that the compositional process organizing the work is easy to grasp." But, she asks, "what to do with this simplicity when tethered to such culturally explosive materials?" One way to understand it, she suggests, is consistent with the demagogue's interest in a visceral connection that dramatically transcends ordinary popularity. "I can't help but see how these provocations," she writes, "can be seen as cynical means for drawing attention to work that might otherwise not spawn much debate."14

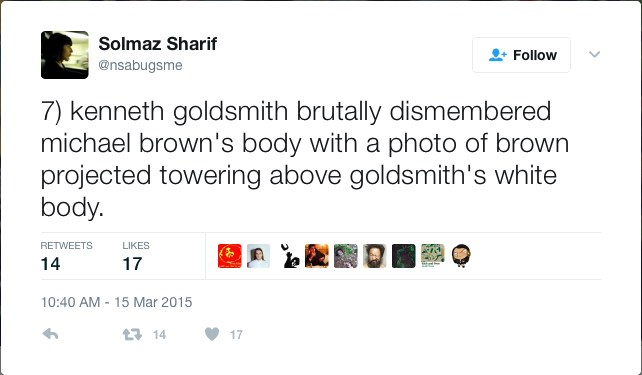

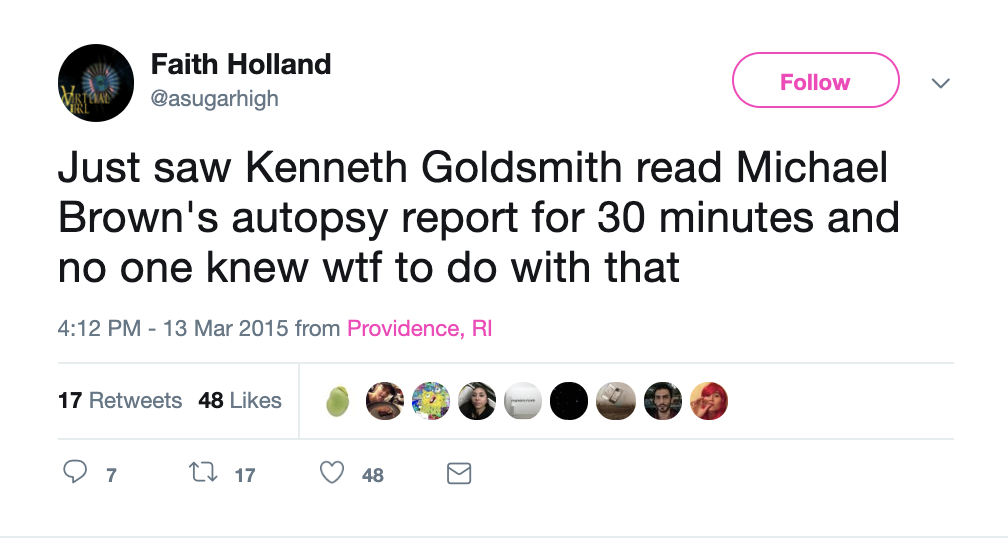

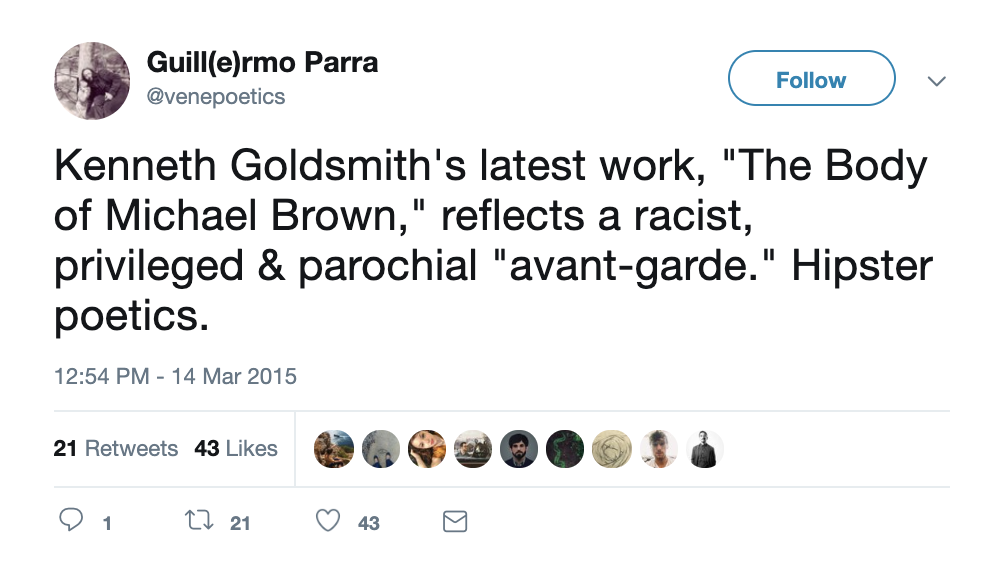

And then, in March 2015, Goldsmith finally goes too far. At a conference at Brown University, he reads a slightly altered transcript of Michael Brown's autopsy report, claiming it as a poem entitled "The Body of Michael Brown." The indictment on social media is swift:

Demagogues, at least in the U.S. context, have tended to seize upon racism as a unifying tactic. Goldsmith, we can imagine, could have achieved his avant-garde populist aims in a variety of ways, but given the heightened publicity and tensions around the Michael Brown shooting, it is easy to see how the desire for a shouting, hollering, on-their-feet crowd would make his appropriation of the incident a near-inevitability.

John Keene's is the clearest and most damning account of the result: "The dismemberment and display of black bodies before white audiences has an ugly history in the US, such that one might view Goldsmith's performance as a form of symbolic lynching."15

The Avant-Garde Returns

In the wake of the Goldsmith affair, Cathy Park Hong's 2014 essay, "Delusions of Whiteness in the Avant-Garde," rises to prominence as the critical work of the moment. The essay traces the racial exclusions of avant-garde poetics and poetic communities throughout the twentieth century. And it is this critique that makes the essay instantly relevant: it gives a historical context for Goldsmith's actions. But it is the essay's final sentences that I find myself reading again and again.

Fuck the avant-garde, Hong writes. We must hew our own path.16

Fuck the avant-garde. What a weird phrase. What an impossible contradiction. After all, fuck the [institution of art] is the ur-formulation of avant-garde rhetoric, because avant-gardes are first and foremost defined as art movements that refuse to accept the premises of bourgeois art institutions.

This is Bürger's foundational claim: the term "avant-garde," he tells us, describes art movements that critique "art as an institution," defined as "the distribution apparatus on which the work of art depends, and the status of art in bourgeois society."17

Fuck the avant-garde makes sense, then, as a response to the institutionalization of the avant-garde, a process that begins — in Bürger's telling — with the subsumption of the historical avant-gardes by the market after WWII. In Hong's narrative, this institutionalization gives us not only the thoroughgoing commodification of the avant-garde, but also the systematic exclusion of nonwhite experimentalists from its very definition.

Fuck the avant-garde, like avant-garde populism, sits at the margins of compromise aesthetics. Like compromise aesthetics, it, too, questions the notion that formal experimentation is by definition politically oppositional. Fuck the avant-garde tells us that what looks like oppositional form has, in fact, been complicit with the most egregious injustices of the dominant culture throughout the postwar period.

But by taking on the very institutions that shape, support, and give credibility to literary culture, fuck the avant-garde might also be understood as the only legitimately avant-garde position that one can take today.

Meanwhile, the avant-garde has been fading in and out of consciousness, hanging on the edge of death.

But suddenly shouts are heard echoing through its chamber.

At first it is just Hong's voice: "fuck the avant-garde." But then there are more. "When did it become the job of the enlightened 'avant-garde' artist to fuck with the minds of people of color?" asks Brian Kim Stefans.18 Chris Chen and Tim Kreiner can be heard describing the resumption of a debate that sets "Anglo-American avant-gardes against a range of antiracist and feminist poetics."19 And then there is the cacophony of voices on Twitter, Facebook, and many, many blogs, forming a chorus: fuck the avant-garde.

Food. Light. Warmth. The avant-garde stirs.

Renato Poggioli: "Whenever [the] spirit of hostility and opposition appears, it reveals a permanent tendency that is characteristic of the avant-garde movement."20

The avant-garde stands up. Noticing open ductwork on the ceiling, it places the cot vertically and crawls out to freedom.

Choosing Sides

A second scandal follows almost immediately, this one erupting over conceptualist poet Vanessa Place's Twitter project, Tweeting Gone With the Wind, which consists of a series of tweets of direct quotes from Margaret Mitchell's novel that were spoken by the character "Mammy," played by actress Hattie McDaniel in the film version of the book. Using a profile photo of McDaniel, the Twitter project gives Mammy's lines without attribution, alteration, or disclaimers. Place's intention is to provoke the Mitchell estate into suing her for copyright, therefore forcing the Mitchells to publicly claim of ownership of racist language. The result, however, is a performance that looks suspiciously like blackface, as a white poet spits racist lines out into the public sphere with a black woman's face as her avatar.

An anonymous anti-racist collective calling itself The Mongrel Coalition Against Gringpo begins a Twitter campaign against the work, and a related group of poets develops a petition demanding that Place be removed from the conference programming subcommittee of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP). The AWP responds almost immediately, agreeing to remove Place. The Mongrel Coalition demands additional denunciations of Place by central members of the poetry community. Many comply. Those who refuse are targeted by further Twitter campaigns.

The timing is strange. It had only recently become a commonplace notion that, with the death of the avant-garde imminent, divisions within the poetry community could be healed; lines of communication opened; camps dissolved. Hybridity, compromise, and pluralism seemed to have won out over antagonism.

But suddenly one had to choose sides.

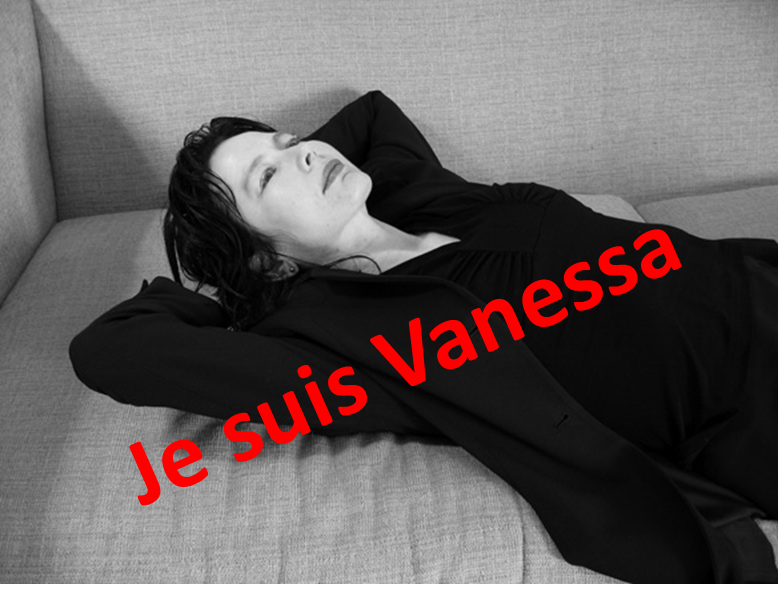

"Je suis Vanessa!"21 reads the headline of poet and critic Ron Silliman's popular blog. The phrase recalls the "Je suis Charlie" campaign that followed the murders at the offices Charlie Hebdo, a rallying cry for freedom of speech against those who would use violence to suppress dissent.

The Charlie Hebdo artists, according to Silliman, were targeted for their exercise of "the most important of all rights . . . the right to blaspheme." And those artists who, out of concern for the offensive nature of the Charlie Hebdo material to Muslims, protested the PEN Freedom of Expression award that was given to the surviving artists? Silliman argues these artists "may think they are being 'culturally sensitive,' but they are in fact siding with the very same forces that, for example, banned 'degenerate works of art' during the Nazi regime."22

Similarly, Silliman argues, those who forced the AWP to remove Vanessa Place from the programming committee are an "online lynch mob" that is "no better — and hardly any different — from the fascist jackboots tossing books into a bonfire in Prague some 80-odd years ago."23

"There really is no middle ground. None," says Silliman.24

So much for compromise.

And Silliman is far from being the only poet to characterize the group as undemocratic.

Aaron Kunin, for instance, similarly describes Place's denouncers as a potentially violent revolutionary force:

Place's accusers either don't understand power, don't like power, or are pretending not to like power. Based on my observations, I'm going with the third option.

Ostensibly Place's accusers speak on behalf of the powerless, and are powerless themselves. . . . From a position of seeming powerlessness, Place's accusers leveraged the cancelation of most of her appearances in May, June, and July. I call that power. In fact, I call it an abuse of power . . . By using the little bit of rhetorical power that they have, they are showing what they would do if they had other kinds of power. It isn't pretty.25

And even as Kim Calder reminds her readers, rightfully, I think, about the necessity of dissent and polarization to a healthy democracy, she too sees the Mongrel Coalition as going too far. "Let us not forget," she writes, "that the left, too, has its authoritarian orders."26

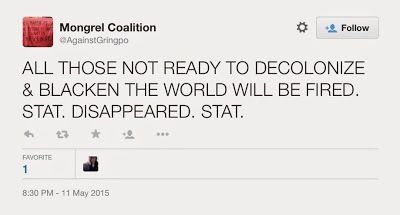

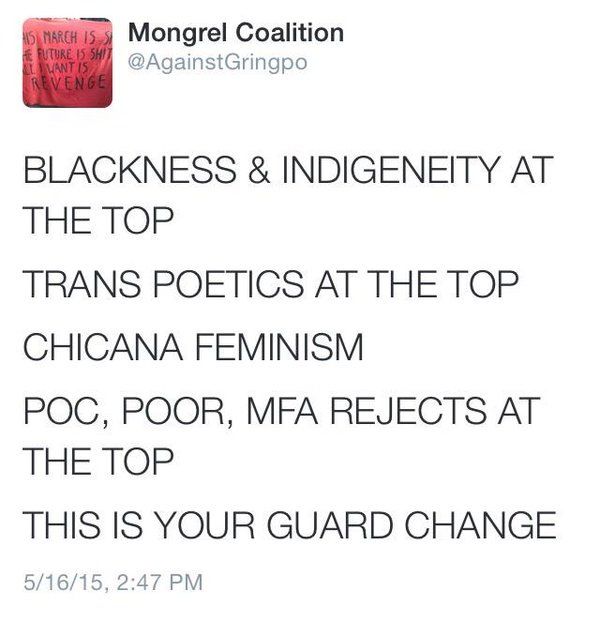

The Mongrel Coalition, for its part, does nothing to assuage these fears. In fact, they threaten authoritarian tactics:

They espouse unapologetically hierarchical arrangements of power:

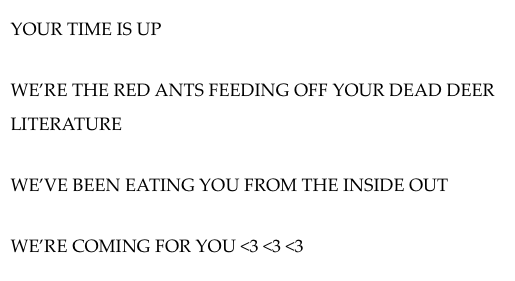

And they issue what appeared to be threats of aesthetic, if not bodily, harm:

These statements are taken, in turn, as threats, assaults, and forms of institutional violence. Certainly, some of work of the Mongrel Coalition — a majority even — is consistent with the Twitter form of the personal callout. The callout is a form of "naming-and-shaming," a tactic widely used by social movements, lobbyists, human rights organizations, and consumer protection advocates. But the personal stakes of social media mean that it can easily cross a line into bullying. Whether a callout is part of a tactical name-and-shame campaign or an act of bullying has everything to do, as Calder and Kunin point out, with the positions of caller-outer and the called-out on a power hierarchy. And that hierarchy is sometimes fuzzy; depending on who you are you might see it very differently.

This is why, when the Mongrel Coalition first appears on the scene, my first impulse is to recoil. I see friends threatened with retaliation for associating with poets and scholars who are called out by the Mongrels. I worry about the policing of art and discourse. I wonder what this means for the future of art.

I have shameful thoughts. Thoughts like, who are they to tell me what to do? Quiet, indignant conversations in which I find myself repeating, it's complicated. I hear myself saying that and I hear it as a copout but I don't know what else to say. Mostly I find myself seeing myself as the them to the Mongrel Coalition's us, and I don't like it and it makes me angry.

But then one day I find myself doing something I've never done before: I go onto the Mongrel Coalition's Twitter page and spend a couple of hours reading it straight through. And the result is not anger, but pleasure. There is so much joy on that page, so much theatrical reveling in the power of hyperbole. I realize, seeing their Tweets as a body of work, that reading all of the Mongrel Coalition's communiques as callouts or threats requires ignoring some of their most conspicuous formal features — their all-caps, their work with visual type features such as emojis and gifs, their use of the anonymous third-person plural.

And it occurs to me that I've seen these features before. And I've felt this particular kind of pleasure — a reveling in the over-the-top, a feeling of the political truth of the shamelessly hyperbolic — I felt it for the first time at the age of 13 when I went to a Bikini Kill concert and saw a group of women with the word SLUT written on their exposed stomachs in bold sharpie. I felt it again when I read the SCUM Manifesto in graduate school, hanging on every crazy word.

It's then that I begin to think that the Mongrel Coalition's anti-avant-garde communiqués should be understood to themselves fall into an important avant-garde tradition: the manifesto.

The Manifesto

The manifesto, according to Janet Lyon, "refuses dialogue or discussion; the manifesto fosters antagonism and scorns conciliation. It is univocal, unilateral, and single-minded. It conveys resolute oppositionality and indulges no tolerance for the fainthearted."27 And yet, as Lyon reminds us, that although the manifesto "appears to say only what it means, and to mean only what it says," the it is, instead an "iterable structure" that is "more than 'plain talk': the manifesto is a complex, convention-laden, ideologically inflected genre."28 It is therefore surprising how often the Mongrel Coalition's writings have been taken for "plain talk," especially by those who read their provocations as unfair, or mob-like, or totalitarian, or unconsidered in their targets. When read through the tradition of the manifesto, it is clear that the Mongrel Coalition uses hyperbole, sentimentality, and theatricality to harness rhetorical power, which in turn becomes real power in the literary domain.

As Martin Puchner explains, we might think of political manifestos as performative insofar as they are "texts that are singularly invested in doing things with words, in changing the world." Artistic manifestos, on the other hand, "with their over-the-top statements and shrill pronouncements" can seem to be primarily theatrical. "Yet," Puchner writes, "both performative intervention and theatrical posing are, to some degree, at work in all manifestos."29

For this reason, I think Kunin is incorrect in his argument that the group's members "either don't understand power, don't like power, or are pretending not to like power." The Mongrel Coalition does understand power, does like power, and is not pretending not to like power. In fact, by drawing directly from the iterable form of the manifesto they are aligning themselves with a form of militancy that has power as its unapologetic aim.

The manifesto is an unabashedly illiberal form. As Lyon argues, it "eschews [the] gradualist language of debate and reform."30 But on the other hand, Lyon tells us that the manifesto was the rhetorical form perhaps most intimately tied to the emergence of liberal democracy in the first place. She writes: "When political and economic developments in post-Enlightenment Europe generated the modern concepts of equality and rational autonomy — at this moment the manifesto appeared as a public genre geared to contesting or recalibrating the assumptions underlying a 'universal subject.'"31 The manifesto has a dialectical relationship with the health of any liberal democracy, challenging liberal universalism in order to ensure that the promises of liberal democracy — freedom, equality, and popular sovereignty — are not restricted to a privileged few.

We know that the manifesto has historically been the preferred rhetorical vehicle for the avant-garde. Poggioli's definition of avant-gardism, for instance, sounds very much like Lyon's definition of the manifesto. For Poggioli, the avant-garde is "an argument of self-assertion or self-defense used by a society in the strict sense against society in the larger sense."32 And like Lyon, he sees this particular combative stance as having an intimate connection with liberalism.

This connection to liberalism may seem counterintuitive. After all, aren't most avant-gardes anti-liberal? We might think of the Futurists with their fascist allegiances or the Situationists with their anarcho-Marxist sympathies. But for Poggioli, these conscious political alliances pale in comparison to the fundamental reliance avant-gardes have on the existence of a liberal democratic political order. Because the avant-garde, he argues, can only exist in a society that tolerates some degree of dissent, it "can only flower in a climate where political liberty triumphs, even if it often assumes an hostile pose toward democratic and liberal society." Furthermore, because the avant-garde thrives on controversy, "the hostility of public opinion can be useful to it."33

The avant-garde along with its privileged form, the manifesto, therefore shares with demagoguery a peculiar place at the margins of liberal democracy: it is predicated on liberal democracy's values, yet it acts antagonistically toward the very liberal democratic ideals it relies upon.

The difference, however, is crucial: while demagoguery seizes upon democracy's promise to enact the will of the people, the avant-garde seizes upon democracy's commitment to admit dissent. As a result, we know that demagogues tend to encourage violence from those who feel as if they are representatives of a given society's dominant group — those who feel representative of "the people" — while manifestos represent those who feel as if they have been shut out of the very definition of "the people."

Illiberal Democracy

So what does fuck the avant-garde mean?

Despite the fact that it is a clear critique of the avant-garde, the position established by fuck the avant-garde retains a key feature of the avant-garde impulse: it reminds us that illiberalism is crucial to democracy's survival.

This is true even if specific instances of opposition disintegrate, lose relevance, and become appropriated. This process — the process by which antagonism become recognized and mainstreamed, leaving room for further antagonisms — is the very engine of both aesthetic and political change.

Lyon writes, "Wherever the universal subject is, there the manifesto shall be; for since the mid-seventeenth century the manifesto has acted out both an affirmation of and a challenge to universalism."34 The manifesto's vitality, in other words, has historically been linked to liberalism's vitality. When a group is excluded from the liberal definition of the universal subject — when a group is not recognized as consisting of equal, autonomous, free individuals — the manifesto is the rhetorical form that emerges to forcefully insist on the expansion of liberal values.

To reverse Lyon's claim, we might say that if the manifesto disappears, that signals one of two possible situations. In one scenario, it means that liberal modernity has succeeded to the point where each individual has been granted full and unquestioned recognition, justice, and equality. In another scenario, it means that we have entered a paradigm beyond the norms of liberal democracy, a paradigm in which struggles for justice are no longer recognized as legitimate.

Poggioli, writing about the avant-garde, imagines something like this second possibility:

[A]vant-garde art is destined to perish only if our civilization is condemned to perish, that is, if the world as we know it is destined to fall before a new order in which mass culture is the only form of admissible or possible culture, an order that inaugurates an uninterrupted series of totalitarian communities unable to allow a single intellectual minority to survive, unable even to conceive of exception as valid or possible.35

Writing in 1962, Poggioli saw totalitarianism as the most likely version of this political reality. But the inability to "conceive of exception as valid," the suspicion toward any "intellectual minority" with teeth, the celebration of "mass culture" as final and all-inclusive: these are all features that can emerge if dissent is seen as outmoded, if politics are reimagined as the affirmation of personal expression, if the mandate to compromise supplants all us's and them's, and if liberalism itself becomes hardened into a utopian ideology.

Rachel Greenwald Smith is associate professor of English at Saint Louis University. She is author of Affect and American Literature in the Age of Neoliberalism (Cambridge, 2015), editor of American Literature in Transition: 2000-2010 (Cambridge, 2017), and co-editor, with Mitchum Huehls, ofNeoliberalism and Contemporary Literary Culture (Johns Hopkins, 2017). Her essays have appeared in The Los Angeles Review of Books, Novel: A Forum on Fiction, American Literature, Mediations, and elsewhere.

References

- Cole Swensen, "Introduction," in American Hybrid: A Norton Anthology of New Poetry, eds. Cole Swensen and David St. John. (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2009), xxi.[⤒]

- Alan Shapiro, "Odd Splendor: A Conversation with Early Career Poets of Color." Gulf Coast 27, no. 2 (2015): 239.[⤒]

- Johanna Drucker, Sweet Dreams: Contemporary Art and Complicity (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005), xi.[⤒]

- David St. John, "Introduction," in American Hybrid: A Norton Anthology of New Poetry, eds. Cole Swensen and David St. John. (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2009), xxviii.[⤒]

- Drucker, Sweet Dreams, xiv.[⤒]

- Shapiro, Alan, "Odd Splendor," 275.[⤒]

- Kenneth Goldsmith, "Unedited Transcript: Kenneth Goldsmith," BOMB 117 (Fall 2011).[⤒]

- "Transcript: ABC News anchor David Muir interviews President Trump," ABC News, January 25, 2017. [⤒]

- Michael Signer, Demagogue: The Fight to Save Democracy From its Worst Enemies (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2009), 22.[⤒]

- Ibid., 35[⤒]

- Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Michael Shaw (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).[⤒]

- Maggie Nelson, The Art of Cruelty: A Reckoning (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 2011), 6.[⤒]

- "Kenneth Goldsmith," The Colbert Report, Comedy Central, July 23, 2013.[⤒]

- Sueyeun Juliette Lee, "Shock and Blah: Offensive Postures in 'Conceptual' Poetry and the Traumatic Stuplime," Evening Will Come: A Monthly Journal of Poetics 41 (May 2014). [⤒]

- John Keene, "On Vanessa Place, Gone With the Wind, and the Limit Point of Certain Conceptual Aesthetics," J's Theater, May 18, 2015.[⤒]

- Cathy Park Hong, "Delusions of Whiteness in the Avant-Garde," Lana Turner 7 (November 2014). [⤒]

- Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, 22.[⤒]

- Brian Kim Stefans, "Open Letter to the New Yorker," arras.net, October 4, 2015.[⤒]

- Chris Chen and Tim Kreiner, "Free Speech, Minstrelsy, and the Avant-Garde," The Los Angeles Review of Books, December 10, 2015.[⤒]

- Renato Poggioli, The Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Gerald Fitzerald (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1968), 26.[⤒]

- Ron Silliman, "The most important of all rights . . ." Silliman Blog, May 22, 2015.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Aaron Kunin, "Would Vanessa Place Be a Better Poet if She Had Better Opinions?" nonsite, September 26, 2015.[⤒]

- Kim Calder, "The Denunciation of Vanessa Place," The Los Angeles Review of Books, June 14, 2015.[⤒]

- Janet Lyon, Manifestoes: Provocations of the Modern (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999), 9.[⤒]

- Ibid., 9-10.[⤒]

- Martin Puchner, Poetry of the Revolution: Marx, Manifestos, and the Avant-Gardes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006), 5.[⤒]

- Lyon, Manifestoes, 31.[⤒]

- Ibid., 32.[⤒]

- Poggioli, The Theory of the Avant-Garde, 4.[⤒]

- Ibid., 95.[⤒]

- Lyon, Manifestoes, 32.[⤒]

- Poggioli, The Theory of the Avant-Garde, 109.[⤒]