Web 2.0 and Literary Criticism

For scholars working on African literature, the challenge in describing the "contemporary" moment very much lies in how to make sense of the impact that new digital technologies have had on reading, writing, and the formation of literary cultures and communities. One of the most notable developments within Africa over the last 20 years has been the rapid expansion of mobile phone technology, a veritable social and technological revolution whose effects have been felt across nearly every facet of modern life. By enabling access to the internet and other telecommunications networks in places where telephone lines and broadband cables are nonexistent, smart phones have reshaped everything from how people work to the nature of personal relationships. Nowadays, WhatsApp and Twitter serve as important sources for news and as staging points for grassroots political movements (as seen in the #FeesMustFall, #RhodesMustFall, and #ThisFlag movements)1; texting and social media have provided younger people with new ways to maintain friendships and pursue sexual relationships, and to do so outside of family and social surveillance; and access to mobile phones and the internet has been championed by development economists as a low-cost tool capable of increasing access to health care, fostering transparent governance, and cultivating entrepreneurial initiative.2

Literary culture has been anything but immune to these developments. While hard data on the impact that mobile phones have had on reading practices in Africa is still emerging,3 there is at least a widespread perception that younger readers "are dependent on mobile technology for their media consumption," and that this situation has affected "how African authors interact with each other and with readers."4 Which leads one to wonder: If the use of mobile devices as the primary medium for reading has altered the relationship between authors and readers, what is this new relationship? How does literary culture in the age of information technology differ from the practices of past generations? How are publishers, editors, authors, and readers making use of new digital platforms? What sorts of writing are available on these platforms, and what terms best describe the literary culture we see emerging there with respect to the self-conceptions and interactions of authors and readers?

These questions are all the more pressing because literary studies has been somewhat slower than other fields in examining the impact of information technology in Africa.5 Part of the reason for this may perhaps have to do with how new media have exacerbated certain longstanding tensions within the literary field. Both literary writers and scholars have often worried about who is reading African fiction and what this audience says about the ideological construction of African literature. The most well-known instance of this line of thinking is doubtless the Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o's call to abandon English and return to African languages with a more organic connection to their intended audiences.6 But Ngũgĩ's primary anxiety — that English-language literature speaks more directly to the experiences and ideology of a foreign audience than to those of a domestic one — tends to get repeated in one form or another every few years — as, for example, in Eileen Julien's critique of the "extroverted" nature of the African novel,7 or in Sarah Brouillette's recent archaeology of elite African literary networks and the West-based donor systems supporting them.

When viewed from the perspective of such critiques, the types of literature that make explicit use of information technology often bifurcate into two opposing groups. On the one hand, we have a small number of popular fictions, which manage to go viral on social media (much like the Instagram poetry and Twitter literature that Seth Perlow and Christian Howard examine in their contributions to this cluster). Take for example Mike Maphoto's wildly popular blog, "Diary of a Zulu Girl." The story of a young woman from KwaZulu-Natal who has come to Johannesburg for school, "Diary of a Zulu Girl" was released in serial format, with Maphoto posting several new installments to his blog each week. Over the first 6 months of its existence, Maphoto's blog captured an astonishing 10 million page views, and inspired the creation of a number of copycat "diaries." Most impressive, the circulation of Maphoto's story took place almost entirely on social media — a fact that has often been held up as a sign of digital literature's revolutionary potential for disrupting the publishing industry and reaching a more popular audience.8

On the other hand, we have a growing number of new literary journals that have taken advantage of the low costs associated with online publication to launch new digital platforms — journals such as Brittle Paper (2010-), The Kalahari Review (2012-), Bakwa (2012-), and Omenana (2014-). These online journals share a number of common characteristics, many of which Tsitsi Jaji identifies in her work on the now-defunct Zimbabwean magazine StoryTime.9 They are often (though not exclusively) hosted on easy-to-build WordPress sites, which allow for speedy publication with little financial overhead, and for reader comments. They are also more self-consciously "literary" than popular viral narratives, with many lauding themselves as budding centers of "intelligent" discourse.10 Finally, they tend to be acutely sensitive to the restricted scope of their audiences. Many online journals champion their sites as spaces where writers can free themselves from the expectations of Western audiences and experiment with new genres — even though, as most acknowledge, this decision means abandoning commercial viability and restricting oneself to a small audience of fellow writers and intellectuals.11 Brittle Paper, for example, distinguishes the "obsession with realist fiction that defined older generations" from the desires of a newer generation more interested "in speculative writing — fantasy, science fiction — but also in experimental narratives, pulp fiction, and other offbeat genres."12 In a similar manner, The Kalahari Review envisions itself as a "space for Africa to speak for herself" through "a variety of styles of writing and art" — styles which, the magazine stresses, are not ordinarily represented in the well-known "African voices" that "ring mostly outside of" the continent."13 Brittle Paper is optimistic that there exists a "younger, taste-driven audience" eager for such content, but the more conventional line is sounded by Emmanuel Sigauke, the co-editor of StoryTime, who notes that "there appear to be more writers than readers of genre fiction."14 Writers of such genre fiction, Sigauke notes, often have to rely on "would be writers" for their primary audience, and have to hope that new media will help to "cultivate" a wider "readership" in the future.15

The two types of literature represented by Maphoto's "Diary of a Zulu Girl" and by digital literary magazines are in some ways diametric opposites. One is oriented toward a mass audience but lacks certain core attributes that lend visibility to so-called "literary" forms of writing. (In the case of African fiction, those necessary conditions for visibility would generally consist of the novel form and the use of self-consciously "literary" genres — e.g., the bildungsroman.)16 The other also eschews explicitly "literary" genres, but nevertheless displays an investment in literary culture in its adoption of the form of the little magazine — a form which has been associated with elite, cutting-edge writing ever since the avant-garde magazines of the late nineteenth century. The issue for such little magazines is that their orientation toward a small, discerning "intelligent" audience cuts them off from the mass audience that African fiction has historically seen as vital to its social mission.17 As a result, we are left with two alternatives for contemporary literature in the internet age — neither of which is a perfect fit for the Ngũgĩan ideal of African literature, and both of which seem to call for new methodological approaches to their subject matter.

In order to consider what such an approach might entail, I turn my attention in the remainder of this essay to the Nigerian SF magazine Omenena. As one of the many African digital magazines founded in the past ten years, Omenana provides a useful case study for how writers, readers, and editors are thinking about the stakes involved in digital publication. Like many other digital magazines, Omenana is hyper-aware of who is reading it and who is not, as well as of what this says about the magazine's social role. Unlike its sister publications, though, Omenana has found a solution of sorts to the ever-vexing question of "Who is your audience?" in the language of SF fandom. Omenana's editors have consistently employed discussions of fandom and its close corollary, participatory culture, to rethink the relationship between readers, writers, and texts. In doing so, they provide us with a model for how to think about Afrocentric genre fiction in the age of the internet.

Omenana was first launched in 2014 by two Nigerian journalists, Mazi Nwonwu and Chinelo Onwualu. Nwonwu and Onwualu had met four years earlier at the "Lagos_2060" fiction workshop organized by the architect Ayo Arigbabu, where they and six other aspiring writers had gathered to consider what Lagos would "evolve into in the next fifty years."18 Nwonwu and Onwualu's experience at the conference convinced them that "we have a copious amount of material for speculative fiction here in Nigeria."19 While neither mentions it in their early editorials for the magazine, they were almost certainly also influenced by the critical and commercial success enjoyed by works such as District 9 (2009), Zoo City (2010), and Who Fears Death (2010), which together provided evidence that there was a prospective market for African SF. Given this rising interest in SF, what was most needed, the pair decided, was "platforms where these stories can be anchored."20

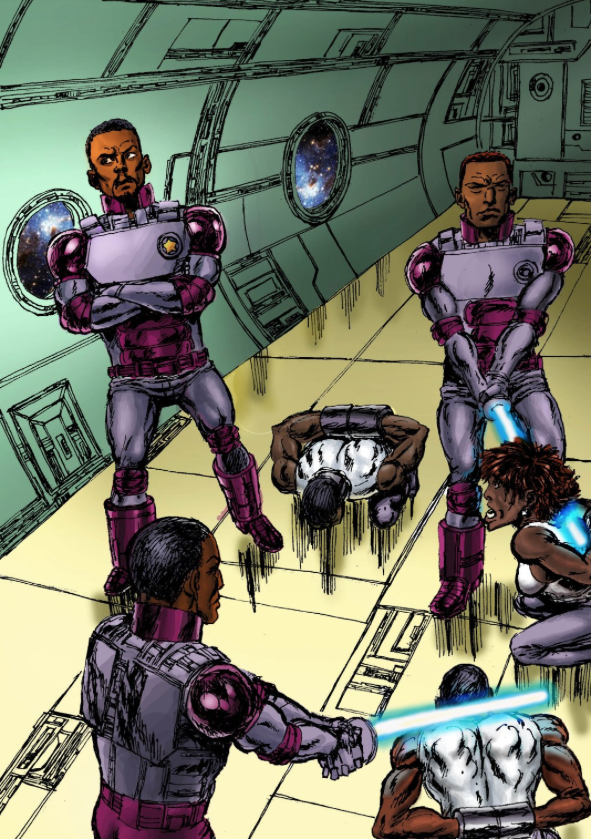

Nwonwu and Onwualu spent the next several years discussing how to create such a platform, and then in planning and designing Omenana and its home website, omenana.com. The result of these labors was revealed on December 2014, when the pair released the first issue of Omenana. Billed as a venue open to "speculative fiction writers from across Africa and the African diaspora,"21 Omenana's first issue is broadly representative of the magazine as a whole. The issue contains a mix of genres, including essays, short stories, artwork, interviews, and editorials. It also features an eclectic mix of new and established voices, with fiction by both professional writers (e.g., Tendai Huchu) and amateurs. (Outside of Huchu, the issue's other contributors consist of an office worker, a graphic designer, an engineer, and another professional writer.)

Perhaps most interesting, Nwonwu and Onwualu chose to publish these stories in two different formats. The stories were first posted to Omenana's website as long strings of text preceded by a single graphic image, and followed by a comments section and links to social media — all very much in the style typical of WordPress sites. At the same time, the pieces were also collected into a single .pdf file and formatted in the style of more traditional "literary" magazines. The arrangement of the text into several tight vertical columns, for example, recalls the design of "quality" middlebrow magazines (e.g., Vanity Fair and The New Yorker), as well as of prominent SF magazines (e.g., Analogue). This decision to collect the website's posts into a printable magazine speaks to a desire to code the assorted works as "literary" in a way that would distinguish them from other forms of internet-based literature.

These two formats point toward Nwonwu and Onwualu's attachment to both of the types of literature I have been discussing: on the one hand, the sort of popular viral sensation we find in the reception of Maphoto's "Diary of a Zulu Girl"; and on the other, the digital literary magazine. We can see both models being invoked in Nwonwu's opening editorial for Omenana's fourth issue. In this short essay, Nwonwu presents the internet as a disruptive technology that can displace Nigerian "literary fiction" from its position of "tight-fisted supremacy over all other forms of literature."22 Here, the promise of Omenana (and of digital publication more broadly) lies precisely in its anti-literary nature — i.e., in its ability to "transform...a literary society that once sneered at genre fiction."23 Such sentiments envision Omenana as something akin to Maphoto's "Diary of a Zulu Girl" — an easily sharable archive of nonliterary fiction ready to be disseminated through viral channels.

And yet, in the same editorial Nwonwu acknowledges that Omenana, like other digital magazines, focuses more on the efforts of an insulated writing class than on popular appeal. There is a marked emphasis on the need for "Africans...to tell their own stories, as this is the best way to own the narrative about Africa and to capture the changing face of the continent."24 Notably, this push to create stories is largely disconnected from discussions of the stories' reception — so that what is at issue here is the activity of writers themselves, rather than their reciprocal relationship with an idealized (national) audience (as would have been the case for Ngugi, Achebe, and many of the other classic theorists of African literature). The thorny theoretical issue here is that digital publication has freed writers from having to shape their narratives to fit audience expectations, but this freedom has also partially detached readers from the national audiences that earlier generations of African writers saw it as their social mission to educate. As Brittle Paper puts it, there is no longer an "allegiance" in newer magazines "to some abstract political idea," whether that be nationalism, anticolonialism, or the notion of the artist as teacher. Rather, one tends to write more for fellow genre enthusiasts — an audience often made up of readers "from across Africa and the African Diaspora,"25 but one which lacks the mass participation facilitated by state education systems during the early years of independence, when contemporary literature often served as textbooks for English classrooms.26

If this dilemma is not exactly new, Omenana's solution for dealing with it is. In her personal essay in the magazine's first issue, titled "The Unbearable Solitude of Being an African Fan Girl," Onwualu self-consciously invokes the language of SF fandom as a model for how to reimagine Omenana as a form of participatory culture. In her eyes, the virtue of Omenana is that it can serve as a meeting place for black women who have been marginalized within the SF community. Noting how "invisible" such women can feel, Onwualu argues that publication in Omenana can show that "you are not alone. There are thousands of women just like you all over the continent.... You ask them to come and pour their hearts and stories into this space you've helped to create. You assure them that they are not alone, that in the vast spaces on the worldwide web, there are others like them."27

Onwualu's essay is saturated with such Oprah-esque appeals to therapeutic writing and women's spaces. But these familiar tropes receive a unique inflection when Onwualu gestures beyond issues of writing and authorship and roots them in the particulars of SF fan culture. Indeed, for all that Onwuala imagines authorship as a response to marginalization, her essay focuses almost exclusively on the racial imbalances present in fan culture: the "despair" one feels as a young girl when "the black female characters on your favorite shows are too often written as stereotypical or one-dimensional"; the self-consciousness one feels at being "the only woman at Lagos Comicon who wasn't working or attending with her significant other"; and even the sense of inferiority one feels when one doesn't "have the unlimited bandwidth that your peers in richer countries do," a shortcoming that prevents one from participating in parts of SF fan culture on the web.28

If we think of Omenana as existing within the bounds of this same fan culture, then Onwualu's statements about women's writing seem to collapse together the categories of reader and writer. The women whom Onwualu appeals to are not coded as professional writers, but as the same type of fans who, like her, have been marginalized in SF fan culture. Such blurrings are common to the SF genre, which has historically distinguished itself not only by the intense activity of its fan community (at conventions, through cosplay, and in fanzines), but also by its investment in various forms of amateur writing, from fan fiction and blogs to reddit and Steam message boards. In a sense, Onwualu is using the language of SF fandom to envision amateur writing as a form of self-fashioning, one capable of both reworking SF in its own image and of producing a community of writer-fans. In this reading, sites such as Omenana emerge as platforms where fan culture is coextensive with the stories being told. There is no inherent difference between authors and readers on these platforms precisely because SF stories are presumed to be the quintessential self-expressions of SF fans. The whole point of these stories is to build a participatory space where reader, writer, and critic are fluid, shared identities, parceled out to all involved and not reified into exclusive subject-positions.

While such ideas are well-known within SF studies, they are a far cry from how African literary studies — as well as literary studies more generally — usually conceives of its object. As we continue to grapple with the changing landscape of contemporary African fiction, though, we might do well to take a cue from Omenana and begin to look at literary culture as a participatory space. Not only would this provide us with a new way of thinking about both online literary magazines and the forms of writing found on Facebook and Twitter; it would also enable us to think less about African literature in holistic terms (the African novel, the audience for African literature), and more in terms of the communities that form around particular genres. Doing so may help us to see how readers and authors are not opposing poles of a formalized print-based market transaction, but instead exist within a complex digitally-driven system of reading, writing, discussion — and, of course, enjoyment.

Matthew Eatough is Assistant Professor of English at Baruch College, City University of New York. He is the assistant editor of the Oxford Handbook of Global Modernisms, and is completing a book manuscript with the provisional title Long Waves of Modernity: Global History, the World-System, and the Making of the Anglophone Novel.

Keywords: Participatory Culture, Science Fiction, Digital Magazines, African Literature, Amateurism

References

- #FeesMustFall was a series of student-led protest movements against the South African government's decision to increase fees in 2001 and 2016. #RhodesMustFall was another South African student-led campaign that began when student activities demanded that the University of Cape Town remove a statue commemorating Cecil Rhodes, but soon evolved into a nation-wide campaign to decolonize South African education. #ThisFlag energized protest against the Mugabe regime in Zimbabwe during 2016, and eventually culminated in a national "stay-away day" (i.e., strike) on July 6, 2016.[⤒]

- For two of the more recent and astute analyses of these trends, see Julie Soleil Archambault, Mobile Secrets: Youth Intimacy, and the Politics of Pretense in Mozambique (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017) and Nanjala Nyabola, Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics: How the Internet Era is Transforming Politics in Kenya (London: Zed, 2018).[⤒]

- UNESCO's study on Reading in the Mobile Era (Paris: UNESCO, 2014) provides some initial data on reading practices in Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe, but these somewhat general findings need to be supplemented by much more rigorous country-by-country analyses.[⤒]

- Brittle Paper.[⤒]

- Anthropology, economics, and political science, for example, all have a much more extensive literature on information technology's impact in sub-Saharan Africa. See Julie Soleil Archambault, Mobile Secrets: Youth, Intimacy, and the Politics of Pretense in Mozambique (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 1-9, for a thorough overview of this scholarship.[⤒]

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, Decolonizing the Mind: The Politics of African Literature (London: James Currey, 1986).[⤒]

- Eileen Julien, "The Extroverted African Novel," in Franco Moretti et al., eds., The Novel, Volume 1: History, Geography and Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), pp. 667-702.[⤒]

- See, for instance, Stephanie Bosch Santana's interview with Maphoto in Africa in Words (September 6, 2013).[⤒]

- Tsitsi Jaji, "Can You Hear Africa Roar? StoryTime and the Digital Publishing Innovations of Ivor Hartmann and Emmanuel Sigauke," Journal of Commonwealth and Postcolonial Studies 1, no. 1 (2013): 122-139.[⤒]

- See, e.g., the mission statement for Bakwa magazine.[⤒]

- See, e.g., Jaji, "Can You Hear Africa Roar?" 129-130.[⤒]

- Brittle Paper[⤒]

- "Mission," The Kalahari Review (2016).[⤒]

- Sigauke, paraphrased in Jaji, "Can You Hear Africa Roar?" 135.[⤒]

- Sigauke, quoted in Jaji, "Can You Hear Africa Roar?" 134.[⤒]

- For an analysis of the outsized role that the bildungsroman has played in contemporary African fiction, see Joseph Slaughter, Human Rights, Inc.: The World Novel, Narrative Form, and International Law (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007), pp. 86-139.[⤒]

- Often, this choice to distinguish oneself from early models of African literature is a self-conscious one. See, for example, Brittle Paper's rejection of Achebe and his pedagogic ideals in its mission statement.[⤒]

- Ayodele Arigbabu, "Prelude," in Lagos_2060 (Lagos: DADA, 2013), xi.[⤒]

- Mazi Nwonwu, Omenana 1 (December 2014): 2.[⤒]

- Ibid., 2.[⤒]

- "What We're About," Omenana.[⤒]

- Mazi Nwonwu, Omenana 4 (September 2015): 2.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- "What We're About," Omenana[⤒]

- For an extended discussion of how educational institutions promoted African literature during the post-independence years, see Peter Kalliney, Commonwealth of Letters: British Literary Culture and the Emergence of Postcolonial Aesthetics (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 178-217. [⤒]

- Chinelo Onwualu, "The Unbearable Solitude of Being an African Fan Girl," Omenana 1 (December 2014), p. 34.[⤒]

- Ibid., 33-34.[⤒]