The Body of Contemporary Latina/o/x Poetry

In her monograph, Boricua Literature, Lisa Sánchez González argues that in the face of national, colonial, and institutional erasure, Boricuas — the Taíno-derived demonym for Puerto Ricans — find themselves disappeared from the U.S. canon and, in effect, are a "paperless" people. But the insistent presence of the damné, or those condemned to the underside of the modern/colonial project, represents a "challenge to paperlessness" through the production of "transracial, translingual, and transcultural" works.1 Such productions are embodied practices that refuse silencing and erasure by bringing the Boricua subject to the fore as valuable and knowing human subject and documenting the quotidian through radical and decolonial political aesthetics.

We can understand this corpus as part of the decolonial turn. Conceptualized by Boricua philosopher Nelson Maldonado-Torres, the decolonial turn refers to "an epistemic, practical, aesthetic, emotional, and oftentimes spiritual repositioning of the modern/colonial subject by virtue of which modernity, and not the colonized subject [ . . . ] appears as a problem."2 Boricua aesthetics — what I examine in this essay in terms of poetics and photography — turns the gaze of modernity onto itself, using the production of paper and material as a way to mark the problems endemic to colonization and coloniality.

Long considered the "whitest" of the Caribbean islands, Puerto Rican discourses of racial democracy obfuscate the race, class, and gender logics that support systematic inequality.3 To be clear, Boricua "paperlessness" and its antidote (the creation of paper, material, and other productions) should be understood within racialized, class, and gendered contexts. This is because we must contend with how Afro-Boricuas in general, and Afro-Boricua women in particular, are positioned within the Puerto Rican diasporic cultural imaginary. Much of contemporary Boricua cultural production reflects the lives and concerns of peoples relegated to colonial subjectship and second-class US citizenship. In what follows I briefly examine the work of photographer Frank Espada and a poem by Aracelis Girmay4. In cleaving these works together, I make space for the examination of photo/poetics as insurgent productions and analyze how the body and the quotidian are used as lenses through which to understand and indict coloniality and erasure.

THE SURVIVAL OF A PEOPLE

On October 1, 1979, Frank Espada, a Boricua photographer and community organizer, was awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Grant that would allow Espada to "plan the first federally-funded documentary for the Puerto Rican community in the United States."5 The project provided the resources for Espada to travel throughout the continental United States, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico to document Boricua life. The immense project was the first of its kind and included over five thousand photographs and more than one hundred and thirty interviews. Espada's work as a documentary photographer and long-time community organizer brought a humanizing perspective to a group of people who had long been considered a racial and ethnic scourge in the United States. Espada's work traced modes of survival and thus creatively and ethically represented Puerto Ricans in the United States.

The Puerto Rican Diaspora Documentary Project resulted in an archive that bears witness to the lives and migration of Puerto Ricans in the "entrails of the monster," the United States.6 Espada sought to chronicle history and build collections and national networks, made clear by the many letters Espada wrote to local and national community organizations, universities, museums, and other potential stakeholders. In this way, Espada's work as a documentary photographer was part of a broader effort to subvert narratives of Puerto Rican "paperlessness." In her monograph Listening to Images, Tina Campt articulates the photographic image as a phenomenon beyond sight and focuses on sound, frequency, and the aural as a valuable and necessary intervention in Black diasporic cultural studies and beyond. Campt urges us to understand that the act of "listening to images" as "a practice of looking beyond what we see and attuning our senses to the other affective frequencies through which photographs register."7 In my study of Espada's work I argue that listening to his images, especially his photographs of Afro-Puerto Ricans in the diaspora, requires a widening or a new frequency that sees poetry as deeply tied to images. What poetry can we hear when listen to Frank Espada's Puerto Rican Diaspora Project?

Courtesy of the Duke University David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library

In 1980, Espada's project brought him to the Ballet Hispanico in the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Founded in 1970 by Venezuelan dancer and educator Tina Ramirez, Ballet Hispanico offered ballet, Spanish, and modern dance training to urban youth, many of whom were Puerto Rican. He took photos of a children's ballet class. In Figure 1, we see a young girl paying rapt attention to something happening outside of our view. She gazes ahead with a look of concentration, perhaps learning a new position or choreography. She stands with her shoulders back and is dressed in a black scoop neck top or leotard. Her skin is brown, and the light reflecting off her face and chest creates bright spaces that blend in with the wall behind her. The way her arms are positioned make it seem as if they are placed on each hip (but this part is out of frame) and her hair is tied back in three ponytails: one on each side of her head, which connect to one in the center back of her head. These are tied with a light-colored ribbon and the loose ends of the hair seem to be braided or twisted into curls. She wears small stud earrings and behind her is a ballet barre barely in focus. In offering this portrait of a young Afro-Puerto Rican ballet dancer, Espada offers us a glimpse into Black Puerto Rican girlhood. To be sure, this is not the common image of a ballet dancer, a pastime that is overdetermined by Eurocentricity and whiteness, which often portrays this as a pastime for people who are white and affluent. Beyond this observation, Espada's photograph offers the possibility of refusal: the refusal to reduce Afro-Puerto Rican girlhood into pathological scripts. In listening to this image, we hear a poetics of possibility, of practice, and potentiality. In the collection of photos of the Ballet Hispanico, we see a myriad of children being attended to with warmth by their instructors and in turn we see the young students filled with excitement, intent, and capaciousness.

Courtesy of the Duke University David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library

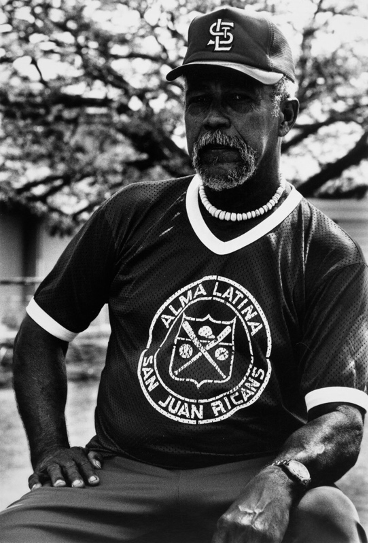

In 1981, Espada left the continental United States and traveled to the Hawaiian archipelago to document the "Hawaiian Experience" of the Puerto Rican diaspora. Espada traced the migration of farmworkers from Puerto Rico to Hawaii in the wake of the 1899 Hurricane San Ciriaco, which devastated agricultural regions, "causing widespread unemployment, hunger and disease" and producing a mass disruption of Puerto Rico's coffee production.8 Rural and impoverished Puerto Ricans were recruited to Hawaii and underwent a grueling journey that included travel by steamships and trains. Those who survived and completed the voyage became de facto indentured servants who were unable to return home. In Figure 2, we see the image of John Matías, president of the Puerto Rican Softball League, coach of the San Juan Ricans team, and former Major League Baseball player. Taken on April 1, 1981 in Lanakila Park, Honolulu, this photo is part of an extended series of images documenting Matías's home, family, and a softball game that involved a multi-generational and multi-racial community of Puerto Ricans and Hawaiians wearing uniforms that read "Aguadilla" and "San Juan Ricans." In Figure 2, Matías, a man of 37-38 years of age, sits facing the camera and stares into the lens, his eyes encircled in shadows. His skin seems to be glowing in the sun which lights the left side of his body. He is deeply tanned with a salt and pepper goatee and wears a Saint Louis Cardinals baseball cap. Matías is adorned with a tight necklace made of shells and a white-edged athletic tee-shirt that reads the name of the team of which he is a coach (San Juan Ricans) and a motto (Alma Latina) encircled around a crest that shows two crossed softball bats, two softballs, and a helmet. His arms, muscled and veiny, are resting on his thighs and we can glimpse the five fingers of his right hand. On his left wrist is a watch and the time is blurred, his left hand is out of the reach of the lens. Behind him is a fence and a large tree that hangs over him like a halo. Of himself, Matías states, "I know my father and mother were Puerto Rican, so I guess I'm gonna be Puerto Rican 'til I die . . . I know deep in my heart que soy Puertorriqueño. I can't speak Spanish too well, but I can say 'soy Puertorriqueño'."9 In documenting the Hawaiian experience of Puerto Ricans, Espada's photographs captured Black Puerto Ricans at the center of community and intramural organizing. Within this community, Matías was a primary motivator who kept others connected to their Puerto Rican heritage though intramural and other sociocultural efforts. In listening to this photo, we can hear the labor of Afro-Boricua community organizing, we can map the intimacies of continually becoming Boricua in Hawaii despite the generational and linguistic gaps, and we can trace the poetics of clinging to a homeland as origin and as practice of individual and collective self-making.

Courtesy of the Duke University David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library

In the summer of 1981, Frank Espada traveled throughout California to document Puerto Rican communities on the west coast. He was at Cabrillo Beach in Los Angeles during the Fiesta de San Juan (San Juan Festival Day). This important gathering, celebrated each year from the 23rd to 24th of June, honors the patron saint of Puerto Rico. In 1981, more than 40,000 people traveled from all of over California and beyond to celebrate. Espada cites David Santiago, festival chairman, as he laments that, "The San Juan Day Festival is one of the few things that bring us together . . . the problem here is the great distances that needed to be covered to organize anything, we are also a minority amongst another minority, the Mexicans." 10 Photos from the archival collection include images of parents and children, close-up candid shots of festival-goers, and photos from behind the stage of musicians and speakers.

Figure 3 shows us a couple dancing salsa during the festival amid a sea of dancers and others who are watching the live music on a stage in the left rear of the photo. The woman clutches the upper right arm of her dance partner and her eyes are closed (either the sun is in her eyes, or the photo is captured mid-blink, or perhaps she's closed her eyes and is listening to the music playing). She smiles widely and her brown shoulders are softly touched by her black hair. It was a sunny and hot day, proven by the many shirtless men facing away from the camera and the sunlight bouncing off of their multi-hued skin. Her partner towers over her and leans his head gently toward the arc of her right shoulder away from the camera. He wears a hat atop a nest of thick curls, a gold necklace is visible just below his hairline, and the back of his tee-shirt sports a large Puerto Rican flag patch or print with the words "Puerto Rico" stitched above it. In this photo one cannot help but see the joy, movement, and chaos of that moment. The dancing couple are surrounded by people moving or standing in every direction and the feeling of the photograph is electric. Espada's photos of this couple at Cabrillo Beach, of Matías in Honolulu, and of the young girl in the Ballet Hispanico add to the archive of Afro-Puerto Rican life in the diaspora. These images and stories are works of poetry that refuse dehumanization and accusations of cultural pathologies. Instead Espada renders his subjects through a lens of love, celebration, and dignity. Espada aimed his camera lens and his efforts to subvert the condition of "paperlessness." In engaging Espada's immense body of work, we become faithful witnesses to the bodies and lives within the work. If we sit with these images of Afro-Puerto life, of the extraordinary, of the quotidian, we can hear poetry.

PEOPLE WHO I LOVE

Aracelis Girmay is a New York City-based Puerto Rican, Eritrean, and African American poet. Across her work, Girmay acts as a faithful witness to people, stories, histories, and moments that often go unseen. Her wielding of words is a refusal of dehumanization, erasure, dismissal. This can be seen, for example, in her collection the black maria, where Girmay traces the entangled histories of the celestial scape (stars, constellations, and the moon) and the sea (the transatlantic slave trade, the countless and continual migrations and deaths of migrants and refugees at sea).11 Her work cleaves together these histories, histories that have often been cleaved apart. To cleave is to bring together and to drive apart; these two meanings emerge from distinct etymological origins. I use this autoantonym to underscore the kinds of labor that Girmay's poetry undertakes and to reveal the dis/junctures that are made possible within poetic forms.

In 2016, Girmay's poem, "You Are Who I Love," appeared online at Split This Rock, an organization that fosters a community of "socially engaged poets." The poem was published online as part of a collection of six poems that were in "conversation" with the inauguration of the 45th president of the United States. In 2019, the poem appeared in Martin Espada's edited collection What Saves Us: Poems of Empathy and Outrage in the Age of Trump12. Espada, a lawyer and poet, is the son of the late Frank Espada, and he has used his father's photographs across many of his writings and reflections.13 What Saves Us includes the work of ninety-three poets and its cover features a photograph from Frank Espada's The Puerto Rican Diaspora Project. For Martin Espada, photography and poetry are cleaved, each attempting to remake and render more human the image of Puerto Ricans, and to make a more just and decolonized self-reflective image of oppressed peoples. Both Frank Espada's photography and Girmay's poetry allow Puerto Rican, Afro-Puerto Ricans, and other people of color to see themselves rendered beautifully as survivors and resistors. These bundles of photography and poetry can be cleaved together (but not apart) because they are visualizations of the human.

Girmay's "You Are Who I Love" is comprised of forty-five stanzas and ninety-nine lines, each describing quotidian moments of human being and human resistance to hatred. The poem describes a series of people in action, "selling roses out of a silver grocery cart" and "in the park, feeding the pigeons" and "cheering for the bees." These statements of witnessing are prefaced by the word "You." In using "You," Girmay hails the reader in general but also points to particular people, potentially people the poet has seen. The poem continues naming people, instances, places, and actions in clusters of stanzas and repeats the phrase "You are who I love." Throughout, Girmay references everyday observations of human sociality. For example, the seventh stanza reads, "You looking into the faces of young people as they pass, smiling and saying, Alright! / which, they know it, means I see you, Family. I love you. Keep on." Here a passing glance or "looking into the faces of young people" becomes a moment to smile and say "Alright!" and this in turn is understood as a loving gesture, a bond of passing kinship.

The poem glimpses or imagines public and private moments, "You dancing in the kitchen, on the sidewalk, in the subway waiting for the train / because Stevie Wonder, Héctor Lavoe, La Lupe / You stirring the pot of beans, you, washing your father's feet." Girmay professes her love to the dancers, be they in the intimacy of their kitchen or in the midst of people on the sidewalk or subway platform. This music that moves them is Black and Puerto Rican and Cuban; it is Black diasporic and Caribbean sounds that spur and inspire people into spontaneous dance. The poem continues back to the realm of the domestic, offering images of someone stirring a pot of beans and yet another person washing the feet of their father. These intimate moments of quotidian life stir in the reader a sense of knowing. Girmay's words take us to these sites as if through flight, and readers are suspended within these encounters of love and tenderness.

Throughout the poem, Girmay references forms of political resistance and community activism. She prefaces these stanzas with the words "You are who I love" and enumerates the ways and forms of their community-driven and political works:

You are who I love, changing policies, standing in line for water, stocking the food pantries, / making a meal / You are who I love, writing letters, calling the senators, you who, with the seconds of your / body (with your time here), arrive on buses, on trains, in cars, by foot to stand in the / January streets against the cool and brutal offices, saying: YOUR CRUELTY DOES NOT / SPEAK FOR ME

Girmay speaks directly about forms of activism: changing policies, writing letters, calling senators, and mass public protesting. She also highlights the activist care work such as stocking food pantries and making meals. In doing so, Girmay acknowledges the kinds of labor that are often unseen. In this poem, which responds to the inauguration of the heterosexist, xenophobic, and racist 45th president of the United States, Girmay chooses to bear witness to how peoples resist the brutalities of the administration through actions of interpersonal and community love. Girmay interprets these actions as the public crying out, "YOUR CRUELTY DOES NOT / SPEAK FOR ME," which is emphasized by being written in capital letters.

Girmay captures longer histories of those who sacrificed or were sacrificed in the making of the settler colonial nation and underscores the histories of violence and hope that undergird it:

You who did and did not survive / You who cleaned the kitchens / You who built the railroad tracks and roads / You who replanted the trees, listening to the work of squirrels and birds, you are who I love / You whose blood was taken, whose hands and lives were taken, with or without your saying / Yes, I mean to give. You are who I love.

Girmay professes her love to those who both "did and did not survive," as well as those who partook in the work of forced reproductive labor ("You who cleaned the kitchens") and the building of national infrastructure ("You who built the railroad tracks and roads") and ecological care ("You who replanted trees, listening to the work of squirrels and birds"). In this stanza, the words "You are who I love" are repeated twice after each set of descriptors. She builds on the first line of "You who did and did not survive" in the second part of the stanza where she bears witness to those "whose blood was taken, whose hands and lives were taken" and, in so doing, to threads together histories of colonialism, forced labor, coloniality, and state-sanctioned and extralegal violence. In cleaving together contemporary forms of political resistance and activism such as protesting and letter writing with longer histories of foundational violence, Girmay shows the reader how bearing witness to resistance and refusal is likewise a practice of learning other/ed histories and being present and available to see these as forms of love and fury and understanding them as a palimpsest.

In the final stanza, Girmay brings us to a moment of encounter and mutual understanding in public and private spaces: in homes, the airport terminal, and a bus depot. She says:

You at the edges and shores, in the rooms of quiet, in the rooms of shouting, in the / airport terminal, at the bus depot saying "No!" and each of us looking out from the / gorgeous unlikelihood of our lives at all, finding ourselves here, witnesses to each / other's tenderness, which, this moment, is fury, is rage, which, this moment, is / another way of saying: You are who I love You are who I love You and you and you / are who

The first line of this stanza brings to mind the words of Audre Lorde's 1978 poem, "A Litany for Survival," which opens with the words "For those of us who live at the shoreline / standing upon the constant edges of decision / crucial and alone."14 The words "edges" and "shores" speak to liminalities, borders that often cleave (apart) peoples from other humans and spaces. This final stanza brings together shared public spaces, usually alienating (airports/bus depots) and shows human affinity in the face of exacerbated national violence and disregard for human life. For Girmay, those who find themselves ("ourselves") in these public and intimate spaces are "witnesses to each / other's tenderness," which is also understood as "fury," "rage," and "love." The poem ends with a series of repetitions of the poem's title emphasized in italics, "You are who I love You are who I love You and you and you / are who." The final seven words refer to the reader, the listener, the subjects of the poem, and to resisters of oppression and lovers of humanity everywhere, "You and you and you / are who." The final words, "are who," leave the reader and listener to complete the sentence by mouthing, reciting, or thinking the words: "are who I love."

After tracing public and intimate moments of quotidian and political actions, Girmay becomes a faithful witness to, and speaks of, love in and despite a climate of political hatred. Lorde's "A Litany for Survival" also tracks the tenderness of love in times of fear. It ends with an encouragement: "So it is better to speak / remembering / we were never meant to survive." I contend that this is precisely what Girmay does. Thirty-eight years after the publication of "A Litany for Survival," Girmay speaks out through poetics toward a deeper and fuller vision of humanity. Girmay's poetic arc of love reveals the oft-unseen and marks the quotidian as extraordinary and refuses to capitulate to racism, sexism, xenophobia, and hatred. Instead, Girmay sees dignity, love, and resistance even in times of "premature death" and disavowal.15

CODA

Espada's Puerto Rican Diaspora Project is a documentation of "you and you" as Girmay's "You are Who I Love" traverses space and place and makes certain that forms of loving can be circulated through poetic images. These diasporic productions of poetry and photography recast the human and become constellations of images and words working in tandem, cleaved, toward decolonization. The quotidian moments captured in the photos of Espada's Afro-Puerto Rican subjects and in Girmay's poem are the facts of everyday Blackness and Black life and survival in the diaspora. The everyday moments that Espada documents invite a form of listening at what Campt calls the "quiet register"; it is listening to the quotidian and the intimate as a central part of the human or the "lowest sonic frequencies of all."16

This lower register is what links Girmay and Espada. They counter paperlessness and create an archive of who is loved. Who is loved in these poems and in these photographs are: colonial subjects, diasporic peoples, those resisting coloniality, and practicing old/creating new ways to love one another. Within Espada's work we must bend our ear to the "lowest sonic frequency" to listen to the poetics of the image, in Girmay's work we must conjure and imagine the people, the bodies, and the immense love she writes about. Espada and Girmay are producing the paper for the paperless. We can listen to his images and read her poetry and behold an indispensable way to see communities that have been disappeared by the archive, coloniality, and erasure. Focusing on poetics and photography as archives made through relation enriches our understanding of seeing and hearing (seeing as listening and hearing as seeing) and gives us tools to create more paper for the "paperless" people.

References

- Lisa Sánchez-González, Boricua literature: A literary history of the Puerto Rican diaspora. (New York: NYU Press, 2001).[⤒]

- Nelson Maldonado-Torres, "Theorizing The Decolonial Turn" in New Approaches to Latin American Studies. Translated by Robert Cavooris (Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2017), 112.[⤒]

- See Kelvin Santiago-Valles, "Policing the Crisis in the Whitest of all the Antilles," CENTRO: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies 8, no. 1-2 (1996): 43-55; and also see Petra Rivera-Rideau "'If I Were You': Tego Calderón's Diasporic Interventions," Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 22, no. 1 (March 2018), 55-69.[⤒]

- Aracelis Girmay, "YOU ARE WHO I LOVE" Split This Rock. January 19, 2017.[⤒]

- Rubenstein archive letter dated Feb 9 1980 to Ricardo R. Fernandez, director of the Midwest national Origin Desegregation Assistance Center - letter is for the "academic humanist" advisory to collaborate with the project.[⤒]

- This turn of phrase was used by Jose Martí in his 1895 letter to Manuel Mercado.[⤒]

- Tina M Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, Duke University Press, 2017), 9.[⤒]

- Espada, Frank. The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Themes in the Survival of a People (Frank Espada, 2006), np.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- I write about the black maria in my forthcoming 2020 book manuscript. See Yomaira C. Figueroa, Decolonizing Diasporas: Radical Mappings of Afro-Atlantic Literature (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2020).[⤒]

- Martín Espada, What Saves Us: Poems of Empathy and Outrage in the Age of Trump (Evanston, IL: Curbstone Books/Northwestern University Press, 2019).[⤒]

- Oscar D Sarmiento, "Mad Love: Martín Espada's homage to Frank Espada's photographic legacy." Latino Studies 17, no. 3 (2019), 288-303.[⤒]

- Audre Lorde, "A Litany for Survival" (Blackwells Press, 1981).[⤒]

- Ruth Wilson Gilmore, The Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 28[⤒]

- Campt, Listening, 6. [⤒]