Ecologies of Neoliberal Publishing

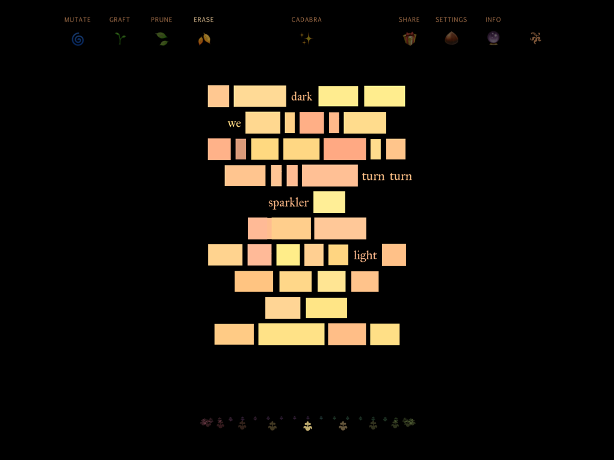

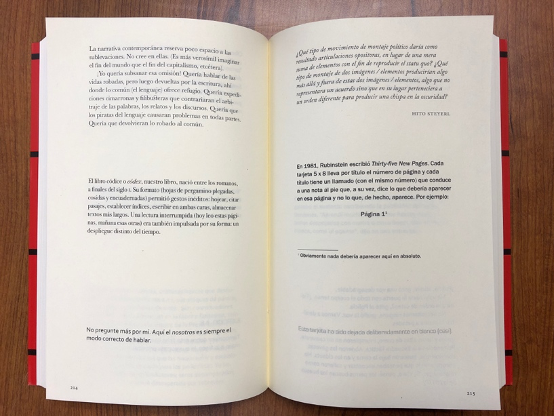

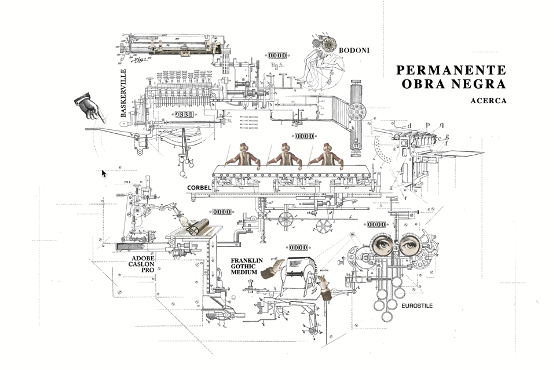

I have been researching hybrid print-digital literary works for a few years now, which means I have given a fair amount of talks about them too. The discussions following these talks often take the same two directions. On the one hand, the engaged members of the audience will, inevitably, recall examples that I've never encountered; word of mouth has helped my research enormously since there is no standardized cataloguing model for this "genre" or "media type." The more skeptical audience members, on the other hand, will ask: "What happens to the enjoyment of reading? Isn't it uncomfortable, cumbersome, or distracting to shift from a book to a computer every so often?" The answers I offer: highlight the way physical presence, the act of handling a book and a computer, is a part of the poetics of a work like Amaranth Borsuk, Kate Durbin, and Ian Hatcher's Abra (2016); insist on the creative exploration of media shifts to reflect on translation, biculturality, and migration through the motif of the sea in J.R. Carpenter's An Ocean of Static (2018); or simply argue that each object affords distinct forms of reading, various reading paths, and indeed different stories, as is the case with Vivian Abenshushan's Permanente Obra Negra (2019). The enjoyment of reading, then, takes place when one realizes how the book and the digital application do what they do and mean how they mean, and realizes how they "talk" to each other.

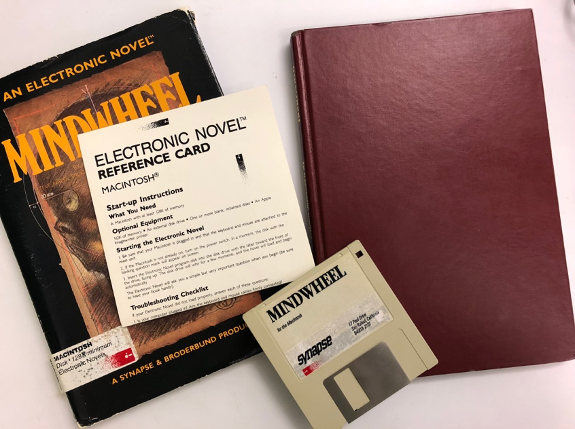

Though there are differences among them, the hybrid print-digital literary works I study are all made up of print codex and digital application. I refer to them as "binding media" to signal the metaphorical stitches joining their components. One will find the digital applications sometimes in a floppy disk or CD-ROM in the back cover pocket, hosted on the web, or in an iPad app — depending on the time of publication. Aside from the recent examples mentioned above, historic examples of print-digital literary works include early titles from the commercial text adventure era, like Robert Pinsky's electronic novel Mindwheel (1984) and Thomas Disch's Amnesia (1986). From the extended age of CD-ROMs in back cover pockets, we find poetry collections like Stephanie Strickland's True North (1997-1998), Luis Bravo's Árbol VeloZ (1998), Augusto de Campos's Não (2003), and Oni Buchanan's Spring (2008).

Picture by the author from the MITH Collection

It is almost needless to say that these are not literary works one can easily find in bookstore displays, take home, and spend the weekend reading on the couch. The print-digital composition of works like these constrains them to particular types of audiences and markets. Binding media works live far into the margins of the world of mass market publishing, both because they are most often published by independent publishers and because their digital applications tend to obsolesce pretty quickly — a feature that renders them commercially viable only for a period of time. If one were to find Pinsky's Mindwheel, Ditch's Amnesia, or Strickland's True North, it would most likely be at a garage sale (or on eBay); and in addition to the book, one would also have to bring home the contemporary Commodore 54, Apple IIe, or, depending on the specific version, some other obsolete computer to read it.1 Less of a technical challenge, at least for now, would be Abra, An Ocean of Static, and Permanente Obra Negra, since they operate on present-day computer platforms. But they are all still published by independent presses — 1913 (USA), Penned in the Margins (UK), and Sexto Piso (MX), respectively — and therefore often rely on grants for their creation, and do not enjoy the powerful marketing and distribution machinery of big publishers.2

In this way hybrid print-digital works participate in two ecologies independent publishing and tech development. This intersection has generated a plethora of aspirations about the cultural and literary relevance of digital technologies. Back in the early eighties when Ihor Wolosenko, co-founder of Synapse Software, approached Pinsky to write a text adventure, his intent was to elevate interactive fiction to the realm of highbrow literature and celebrated authors.3 Wolosenko's intent is likely why Mindwheel is dubbed an electronic novel, and crucially, why it was published as a book — despite Pinsky's own opposition. Presently, aspirations have shifted. The publications of Amaranth Borsuk and Brad Bouse's augmented reality poetry collection Between Page and Screen (2012) and J.R. Carpenter's essay on media metaphors using the cloud The Gathering Cloud (2017) were accompanied by reviews praising enthusiastically the way they heralded the future of the book and publishing.4 Whereas Wolosenko sought legitimacy for creative textual software over the basis of known literary models, reviewers of Borsuk's and Carpenter's works imagine a renewal — and a legitimization— of the pre-digital codex when paired with digital technologies. Authors' positions on the hybrid composition of their works have also fluctuated. In a 2016 New Yorker article about Pinsky's Mindwheel, James Reith relays how the poet laureate resisted having a book accompany the novel, and, despite having written most of it, asked to be uncredited.5 One can only wonder what the association of print book and electronic novel meant for Pinsky, but from Reith's account, it seemed to romanticize the new endeavor of writing an interactive fiction, to ground it, perhaps unfavorably, in a different tradition of literature. Conversely, Carpenter remarks on the importance of hybrid works as "transitional object[s that] operate[] between human and machine languages, times, and spaces, between archives and live voices."6

Aside from the history of the literary phenomenon of binding media, the history of publishing and its many intersections with digital media allow us to see beyond the creative or literary impulses behind print-digital publishing, and into the commercial and corporate ones. Reith reminds us that "in the mid-nineteen-eighties major literary publishers, including Simon & Schuster and Random House, opened software divisions."7 Along the same lines, following the release of Apple's low cost Performa CD, Bob Stein's Voyager's Expanded Books Project created agreements with publishers like Random House, Macmillian, HarperCollins, and NTC.8 In 1997, Joe Moran argued that recent mergers and partnerships between publishers and computer software companies, like Random House's and Broderbund's effort to create Living Books in 1993 and Pearson's acquisition of Software Toolworks (later Mindscape) in 1994, signaled a shift in how books were conceived and produced, thus "challeng[ing] the whole status of the book as a self-contained medium."9

A few concrete instances allow us to gauge the phenomenon more clearly. In 1996, Macmillan Digital Reference launched four Frommer's Interactive Travel Guides. As James A. Martin explains, "each CD was packaged with its paperback guidebook counterpart and sold for about $30."10 Only a couple of years later, the tech manuals press Jamsa launched Kids Interactive, a line of children's books accompanied by CD-ROMs.11 Simon & Schuster Interactive put out A Joy of Cooking with an accompanying CD-ROM in 1998.12 More examples abound, but what I want to underscore is how publishing initiatives that tried, in an effort to innovate and/or reduce costs, to marry print books to digital applications in the mid 1990s encountered two damning shortcomings. First, these initiatives were outpaced by technological developments; by the time seemingly successful hybrid titles were launched, the next tech development would render them passé, if not functionally obsolete. Frommer's CD-ROM guides were easily migrated to the web with all the advantages doing so entails, including a sharp rise in print sales. The other shortcoming was the lack of a market for bookish (to use Jessica Pressman's term) software and software-ish books. When interviewed by Martin, Ted Hill, then the director of product development for Macmillan Digital Reference, acknowledged, "software stores didn't have the shelf space for a niche product like [the CD-ROM travel guides], and bookstores didn't know how to sell them."13

In the last decade, the push has come in the form of mobile and augmented reality (AR). Iain Pears's Arcadia was released to much expectation because of its accompanying iPad app, which is essential to understanding the complex plots of the novel. Meanwhile initiatives like Melville House's Hybrid Book project continue to exist but have failed to create an audience. Perhaps one of the most widely reported initiatives was Penguin's partnering with Zappar in 2012 to publish enhanced versions of several titles of its English Library. Molly Oswaks, reporting the development for Gizmodo, sorely lamented, "Augmented reality, when implemented appropriately, can be a pretty great [sic].... But what can AR tech do for a novel like Moby Dick? Watching a whale animation is not the same as reading the story. Seems like a distraction and a gratuitous bit of packaging."14 Perhaps textbooks are the only exception. While it hasn't been a seamless process, and it's certainly one deserving its own discussion, the addition of digital materials to textbooks has benefited from the ecology (and the economy) in which they circulate. The rapid churning-out of new editions has situated textbooks more on par with the pace of technological developments that have hindered other print-digital projects. Technological imperatives in education and the promise of digital literacies have also softened the resistance to hybrid materials. Similarly, the audience for textbooks is well-identified, sufficiently-addressed, and to a good extent captive. All of these factors have facilitated the migration from textbooks with floppy disks and CD-ROMs to those aided by augmented reality and artificial intelligence.

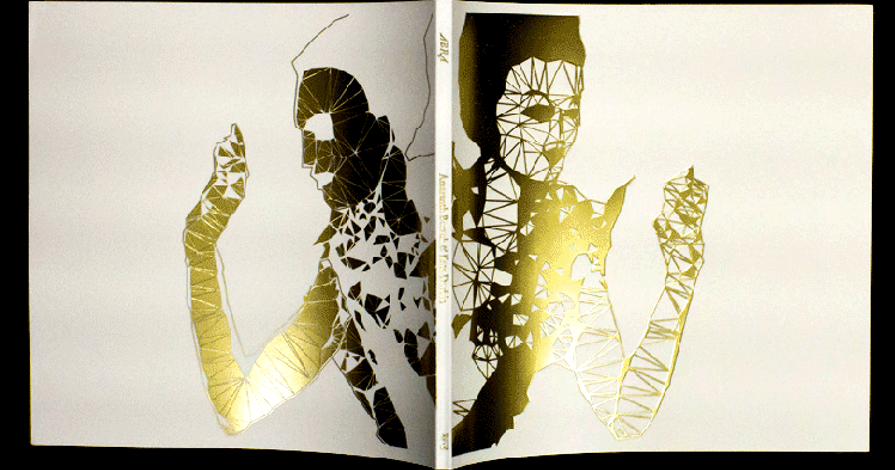

One initiative worth considering separately is Editions at Play, the joint effort between Visual Editions and Google's Creative Lab, that has published beautifully-polished digital titles like Kate Pullinger's Breathe (2018) and Joanna Walsh's Seed (2017). While all the Editions at Play titles are described as books "powered by the magic of the internet," Tea Uglow's We Kiss the Screens (2019) is the first one to include a print codex as well. Like all of Editions at Play's titles, Uglow's work is meant to be read on a mobile device browser — but unlike all the others, We Kiss the Screens can be transformed into a unique print-on-demand book created specifically by following the individual reader's path and color choices, even highlighting the sections not read online. Before Editions at Play, Anna Gerber and Britt Iversen, co-founders of Visual Editions, were already experimenting with book publishing at the intersection of the digital; Jonathan Safran Foer's Tree of Codes (2010) might be the best example of this. The partnership with Google's Creative Lab and the Peabody-Facebook Futures of Media Award has enabled Editions at Play to explore and imagine these intersections more deeply and to break with the conventions of the publishing industry. Indeed, Visual Editions occupies a threshold space between experimental publishing and corporate partnerships. This unique space is signaled, for example, in how Gerber and Iversen characterize their initiative as a "creative agency powered by stories," not as a publisher, a press, or a digital media studio. Their more recent collaborations suggest this unique position too. In addition to working with tech companies like Google, We Transfer, and the Mercedes-Benz, Visual Editions has also collaborated with more bookish partners like Issuu and Penguin Random House. it is undeniable that while they are successful as creators of formally cutting-edge digital and print books, who have not yet suffered from reader or market resistance, Visual Editions/Editions at Play occupy a similar market niche to that of the hybrid print-digital works I mentioned early on. In an interview with Visual Editions editors Anna Gerber and Britt Iverson, Molly Flatt touches on the issue of lack of audience and market when she asks, "But will these super-clever experiments ever appeal to an audience beyond a few digitally curious bibliophiles?"15

The answer I would venture is: likely not, as similar experiments have not attracted large audiences in the past. And this applies to both print-digital books put out by big publishers and the thoughtful, experimental works of publishers like Visual Editions.

What the history of these developments in the publishing industry reveals is that, as a publishing model, print-digital hybrids are most likely to meet with reader resistance and commercial failure — failure for the scale of the mass market. Despite various and recurrent efforts by big publishers, hybrid print-digital publishing, as a standard format, hasn't taken off in popularity or marketability. In independent publishing, print-digital works are written, designed, and crafted uniquely, perhaps even idiosyncratically, so that both media signify in tandem, not just as surrogates, versions, or accompanying pieces. And we could say that it is precisely because of those qualities that such works have not found a home in the mass market landscape where, as Oswaks laments, their endeavors end up looking like merely innovative packaging. Reading such works is, as my audience members intuited, too unwieldy for them to belong in the category of general interest and, of course, even reading older titles at all is contingent on individual readers having access to the right computing equipment.16 What works like Abra, An Ocean of Static, Permanente Obra Negra and others make clear is that there is no easily-standardized way for print matter to be tacked onto a digital application; and vice versa: digital applications can hardly be successful as simple augmentations of the print book. A compound of print codex and digital device very rarely coalesces to become a single media object as happens in the works binding media.

This process of binding takes place through distinct strategies at various points of the creation and production of the work and is far from a one-size-fits-all model. These strategies include technical juxtaposition, as when AR allows a reader to handle print codex and digital device (a computer or an iPad) simultaneously. The printed codes in Between Page and Screen, for example, can only be read on a computer screen via a webcam. Similarly, the highly metafictional interactive novel Ice-Bound by Jacob Garbe and Aaron Reed asks readers to let the protagonist read pages in the book through the iPad's camera. Narrative or poetic sequentiality offers another way in which codex and digital application can be bound. Belén Gache's El Libro del Fin del Mundo and Strickland's poetry collections best exemplify such sequentiality by organizing their works so that readers move back and forth from print to digital objects to complete their reading. Book design is key to media binding. While earlier designs featured back cover pockets that held a floppy disk or a CD-ROM, more recent objects stitch media together with greater cunning by displaying manicule-like icons on the page, icons that lead the reader in and out of the print codex, and/or offering tables of contents that include sections outside of the book.

Interface design by Dora Bartilotti with programming by Leonardo Aranda.

The landscape most propitious for these processes continues to be independent publishing.17 Binding media works do not begin as manuscripts that fit neatly into well-established production processes, and are complex media objects that require the cooperation of actors beyond the scope of traditional trade book publishers. Lisa Pearson, editor of Siglio Press and publisher of Borsuk and Bouse's Between Page and Screen, has stated that her interest is to use the form of the codex more than its content. Siglio declares its mission to publish "uncommon books at the intersection of art & literature." Similarly, Kate Gale, managing editor at Red Hen Press, has pointed out how production quality is what distinguishes independent publishing from the mass market: "for the book to sell, it must look better than the books produced by the conglomerates. The layout, the font chosen, the paper, the design all are calculated to make the book a work of art worth paying for."18 This concern with production value and its impact on sales and distribution, she goes on to explain, makes room for authors to weigh in on the look of their books. These aspirations are clearly stated in a number of presses' websites. 1913 Press is "committed to publishing the baddest in poetry, poetics, prose, & their intersections with the arts of all forms, in handsome book-as-art-object fashion."19 Penned in the Margins "creates publications and performances for people who are not afraid to take risks."20 These kinds of bold publishing endeavors — which are the basis of hybrid print-digital literary works — tied to a steadily growing community of independent publishers and a healthy readership have led Jeffrey Lependorf, the executive director of Small Press Distribution, to characterize the present moment as a golden age of independent publishing.21

One could be tempted to think of these works in terms of Sophie Seita's conceptualization of the provisionally contemporary: a "hotchpotch" of "heterogeneous and dynamic practices."22 Indeed, several of the little magazines Seita studies, like Triple Canopy, ON: Contemporary Practice, and others, share a hybrid publishing model with works binding media. While this is a model that Seita abstracts from avant-garde little magazines, more broadly she states that "contemporary publishing communities...follow the logic of a moveable contemporaneity and often even make 'nowness' rather than 'newness' a thematic and technological focus of their work."23 Thinking about the "nowness" of hybrid print-digital literary works is useful, as doing so highlights the moment of creation and publishing; the marks of a work's contemporaneity are most evidently seen in the medium of the digital application, fastened in the short lived rise and apogee of the technologies that sustain them. For us readers, this "nowness" (now passed) is most acutely felt when disks can't be read, websites go offline, or apps stop being supported.

The products of the three and a half decades between the publication of the first examples of hybrid print-digital works embody a continuous promise of what the future could have been, and an ongoing reminder of what it didn't turn out to be: the paths opened but not taken. Operating in parallel but separate from big publishers, whose print-digital innovations seem to keep on falling flat commercially and aesthetically, independent publishers and creators like Borsuk, Carpenter, Abenshushan, and others offer a landscape of possibilities, those "autonomous universes of cultural production" Bourdieu rightly feared would disappear due to the priority of commercial values.24 These universes persist at the margins of large scale commercial publishing. Following along the current of market driven technological innovations, hybrid print-digital literary works produce exciting and concerning temporal effects. For a very brief period before and after their publication, print-digital works envision futures for literary creation and publishing. But despite their compelling innovation and their artistic mastery, they rapidly become susceptible to technological obsolescence and the "newness" it imposes upon them.

The "nowness" — not just the "newness" — of these works manifests in the enjoyment of reading I mentioned at the outset: the moment when one makes them mean. This mode of reading is not appealing to everyone, but they have found an audience and a media ecology (and an economy) that sustains them.

Élika Ortega is an assistant professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Colorado Boulder. She is currently writing her first monograph, tentatively titled Binding Media: Print-Digital Literature, 1980s-2010s, in which she investigates print-digital works of literature from Argentina to Canada.

References

- Currently, however, there is an online version of Mindwheel, rehabilitated by Steve Hales, one of the original developers, available here.[⤒]

- Abra was awarded an Expanded Artists' Books Grant from the Center for Book and Paper Arts at Columbia College Chicago. Permanente Obra Negra received funding from Fundación BBVA Bancomer. Individual digital pieces from An Ocean of Static were commissioned by various organizations.[⤒]

- James Reith, "When Robert Pinsky Wrote a Video Game," The New Yorker, January 21, 2016.[⤒]

- See, for example, Venn Creative, "Hybrid Texts and Where We're Headed," The Literary Platform, July 2, 2017; and, Joann Pan, "Can Augmented Reality Save the Printed Page?" Mashable, February 3, 2012.[⤒]

- Reith, "When Robert"[⤒]

- Elle Eccles and J. R. Carpenter, "I'm Trying to Think about Migration ... as a Condition of Being in between Places: J.R. Carpenter on Poetry and Translating the Digital," Penned in the Margins,.[⤒]

- Reith, "When Robert"[⤒]

- "Apple Outlines New Multimedia Initiatives. (Apple Computer Inc.; Random House Inc., National Textbook Co., and Macmillan Computer Publishing Inc. Agree to Create Electronic Book Standard for Macintosh Using Voyager Software Format)," IDP Report 13, no. 36 (1992), 4.[⤒]

- Joe Moran, "The Role of Multimedia Conglomerates in American Trade Book Publishing," Media, Culture & Society 19, no. 3 (July 1997), 441-455; 452.[⤒]

- James A. Martin, "PW: Zipping Along the Web: For Guidebook Publishers, Www Is the Current Address of Choice," Publishers Weekly 243, no. 43 (October 1997), [⤒]

- Heather Vogel Frederick, "PW: Jamsa Press Enters Children's Market." Publishers Weekly 244, no. 20 (May 1998).[⤒]

- Jim Milliot, "Simon & Schuster Interactive, Alive and Kicking at Age Five," Publishers Weekly 245, no. 21 (May 1999), [⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Molly Oswacks, "Timeless Classics of Literature Upgraded With Already-Dated Augmented Reality," Gizmodo, May 2012.[⤒]

- Molly Flatt, "We Kiss the Screens Combines Multiple Narratives, Print-on-Demand and AI to Create a Unique Reading Experience," The Bookseller, April 2019.[⤒]

- My research has only been possible by the generous invitations to the Maryland Institute of Technology at the University of Maryland (with thanks to Matt Kirschenbaum), the Electronic Literature Lab at the University of Washington, Vancouver (with thanks to Dene Grigar); and the Media Archaeology Lab at the University of Colorado Boulder (with thanks to Lori Emerson). [⤒]

- Other non-profit publishers have also been behind hybrid print-digital works. For example, Strickland's North was published by Notre Dame University Press, which Buchanan's Spring was published by University of Illinois Press.[⤒]

- Kate Gale, "The World of Independent Publishing." International Journal of the Book 4, no. 3 (2007), 89-94.[⤒]

- 1913. "About" [⤒]

- Penned in the Margins, "About." [⤒]

- Ed Nawotka, "Lependorf to Leave CLMP After 17 Years," PublishersWeekly.Com, August 8, 2018. [⤒]

- Sophie Seita, Provisional Avant-Gardes: Little Magazine Communities from Dada to Digital (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019), 161.[⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Pierre Bourdieu, "The Essence of Neoliberalism," Le Monde Diplomatique, December 1, 1998.[⤒]