The After Archive

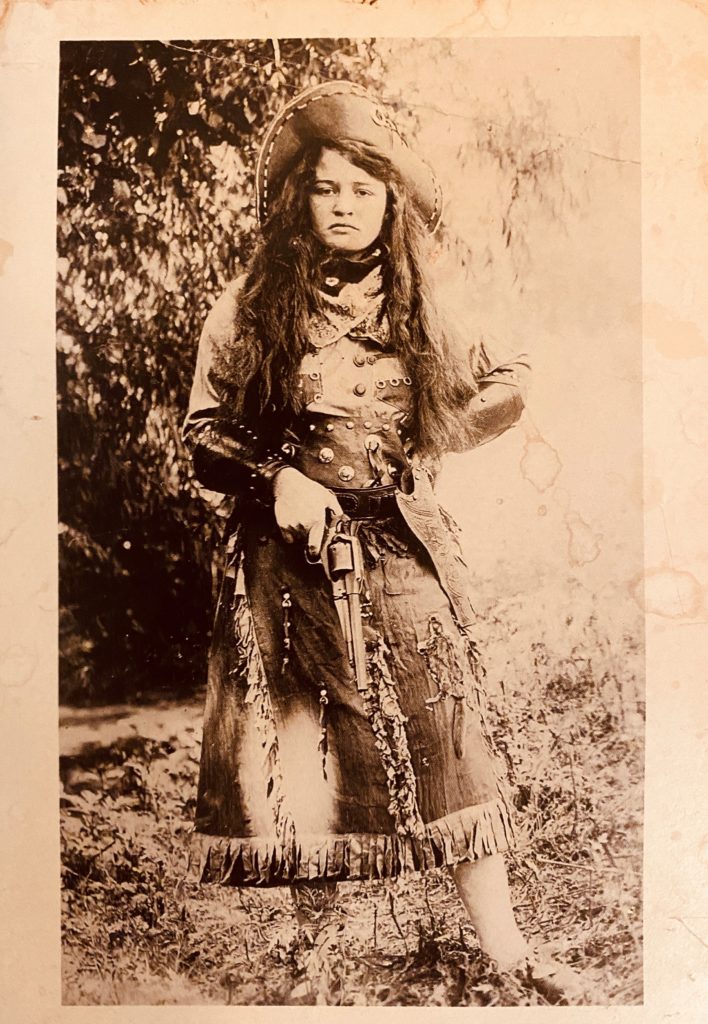

Every day, I look at the sepia-tinted photograph that hangs on my refrigerator, but I don't often see it. The woman at the center of the image has long, coarse hair that hangs down around her face from underneath a wide-brimmed cowboy hat. She looks out at me from underneath the shadowed brim, banded by pale-colored stitches like tracks in wet sand. When I look at her, she pulls my eyes to her face, a clear and plain contrast to the chaos of her clothing. She wears a bandanna like a cross around her neck and her heavy long-sleeved dress is covered in fringe and decorative buttons, beaded tassels and bolo ties, the pelt of a squirrel stitched onto her left thigh right above the knee. She does not look weighted down. Her thick, military-style wrist cuffs are marked with rows of metal studs, transforming her arms into weapons. Behind her stands a background of thick indistinguishable trees. They fade into the flash of the sun or are lost by the failure of the camera. She stands in high, tall grass, which frame her feet. I cannot make out her footwear but I imagine they are moccasins. Her left hand sits on her hip like a warning and in her right hand she holds a pistol, facing down to the ground. She shoots bullets at the camera with her eyes. I love the image of this woman but I have no idea who she is.

This photograph is printed on a postcard and was a gift from my roommate and landlord, Joanne. For two years, from 2003-2005, I rented a room in her apartment, across the street from Columbia University, in a pre-war building. I was a Masters student in the anthropology department and I found the apartment listing on Craigslist.

When I first visited her home, the living room (soon to be my living room) made me gawk. Joanne had covered the walls with dark floral wallpaper, layers of greens and purples and golds that looked like velvet in the dim lamplight. Lining the textured walls were sepia-tinted photographs of nineteenth-century Russian and Romanian Jewish families, encased in golden frames. Given my own Russian and Romanian Jewish heritage, I thought I was walking into a closet in my grandmother's attic.

This is what I think of when I think of family, explained Joanne, the second-generation Irish-American. She told me she had purchased the pictures at antique stores, yard sales, junk shops. She created a form of fantasy kinship-drag in the apartment she inherited from her biological family. These were my people, yet she was claiming them as her family by displaying them across her walls.

These kin-ghosts would watch me for two years, as I moved through our shared space. My relationship with Joanne was never warm and it was often strained. And yet, it was also somehow mediated by the photographs of strangers — she owned the images, but their historical lineage belonged to me.

***

In the spring of 2005, shortly before I moved out of Joanne's apartment, I was cast on a reality television show called Texas Ranch House, a PBS historical recreation experiment set in 1867 West Texas. I would spend three hot, miserable, exhilarating months in the desert during the summer bridging the completion of my MA at Columbia and the beginning of my PhD at Stanford University. I was first cast as the maid for the ranch owner's family but, over those three months, I transformed myself and my role into a cowboy, trading corsets for buckskin chaps and a bonnet for a wide-brimmed cowboy hat. I was an outlier, a loner, the only person without allies or accomplices. I was lonely and isolated and ostracized by the men whose ranks I eventually joined as a cowboy. But I was also resilient, determined. I transcended rank, gender, and the expectations of my companions. If the show had been Survivor, I would have won.

Before I left for Texas, Joanne gifted me the picture-postcard of the stern and beautiful woman. She told me the woman in the photograph was Native American, that she found the postcard in a junk shop, that she looked like a badass.

This is who I imagine you will be, Joanne told me when she gave me the postcard: Joanne, who first re-imagined her own past and then imagined my future. When she first gave it to me, I instantly fell in love with the image and was flattered by this suggestion. Now, I wonder what it means for a White1 woman to gift another White woman a picture of a long-dead maybe-Indigenous woman right before the second White woman travels back in time to West Texas to play dress up on stolen land.

After fifteen years, I want to find its story, I want to know who the woman is and how she became an image on my postcard. And so, in April of 2020, I finally take the picture off my refrigerator. I wonder why I haven't done this before. I wonder how I have carried her with me for so long, never before taking the time to see where her trail would lead me. How have I understood her before this moment? Or how have I not understood her? How have I spent so many years looking at her without really seeing her?

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes writes: "Every photograph is a certificate of presence."2 I was in possession of the certificate but I was unable to feel her presence. Perhaps we only search for stories when we are ready to follow where they lead.

***

The postcard is washed in coppers and gold, like Joanne's chosen family, but there is no date on the back, no number to place her in time. Only a caption that tells me she has been renamed "Squirrel Girl" and that her picture comes from "The Collection of Tyler Beard, True West, Comanche, Texas." Without knowing anything else about the woman, and perhaps influenced by Joanne's suggestion, I read her as either Indigenous or appropriating Indigenous dress. Is she Comanche?

There were many things I did not know when I traveled back in time to nineteenth century West Texas. I did not know that, after the Civil War, Texas became the only Western state to hold onto all its public lands when it joined the union.3 The state was never required to create reservations and, in 1867, the year of my time-traveling adventure with PBS, Indigenous communities were being violently pushed out to neighboring states. The land was patrolled by the Ninth Cavalry: Black "Buffalo Soldiers," many of whom were formerly enslaved and were enlisted to protect White ranchers from Indigenous residents, deemed dangerous and unwelcomed. By the time the Ninth Cavalry left the area, in 1885, the land was deemed safe for White settlers. The Apache were driven to reservations in New Mexico, the Comanche to reservations in Oklahoma. All of this history was marginalized by the myth of the American West and all of these stories were erased by PBS when I traveled back in time to play dress up on stolen land.

When I look at Squirrel Girl, I see resonance with the pictures taken by Edward S. Curtis, the photographer who, from 1906-1930, captured images of Native people across the United States. His photographs were purposefully timeless, his project invested in creating and enforcing a colonial sense of past-ness and sentimentality. I wonder how Squirrel Girl came to be the subject of my postcard-photograph. Who took the picture and what did the woman in the photograph receive in return?

***

Whoever Squirrel Girl was, in the image Joanne gave me as a parting gift, her clothing connected her to a particular sartorial history of Native America and linked her to the region I time-traveled to.

This is who I imagine you will be, Joanne told me. What does this tell me about historical imagination? What does this tell me about the limits and possibilities of the White historical imagination? And how does this indicate or indict the kind of imagining I went on to do in Texas? When I time-travelled to the nineteenth century, I saw my own battle as one of gender: how would I transform myself from maid to cowboy? But I barely considered my Whiteness and I only fleetingly considered how my presence in Texas blocked or covered up other more necessary stories. The image of Squirrel Girl became my hazy beacon in an unclear sea of time travel and historical possibility but I saw her as a woman, and therefore connected to me, before I saw her as anything else. I did not consider our differences, I did not grapple with what it would mean if she were Native. How my Whiteness and her Indigeneity would so profoundly transform our relationship to power, visibility and violence. Now I wonder, who was she? Has anyone told her story? Is she a woman lost in time? How did this photograph come to be?

***

My initial hunt for the woman who became Squirrel Girl leads me first to a Marvel superhero with the same name (an unlikely link) and then down a strange pornography rabbit hole, where I am reminded that if it exists there is porn of it (an even more unlikely link to the image that now sits beside me). And then a dead end.

Next, I ask the internet who Tyler Beard, the man credited on the back of the postcard, is. My search engine takes me to the "Online Archive of California." I learn:

"Tyler Beard (1954 September 1 - 2007 December 20) was renowned for his expertise on cowboy boots and other aspects of Western style. Beard and his wife Teresa opened a Western apparel, boots, and antiques outfit called "True West" in Comanche, Texas in the mid-1980s. Between 1992 and 2004, Beard published five books on Western wear, cowboy boots, and Western décor. This collection contains manuscript drafts and research materials Tyler Beard collected dated 1948-1999 to write The Cowboy Boot Book, 1992; 100 Years of Western Wear, 1993; Art of the Boot, 1999; and Cowboy Boots, 2004."

I assume Beard did not take the photograph. I order a copy of 100 Years of Western Wear. And there she is, on page sixteen, but this time in black and white. My picture-postcard, the woman Joanne imagined I would be, staring back out at me. The caption reads:

"I have affectionately named this cowgirl 'Squirrel Girl' because of the pelt sewn to her skirt. This photo was taken about 1910. You can tell that Annie Oakley and Calamity Jane were influential among the female followers of fashion, even in their own way."

There is no more information about this woman: Beard has replaced her story and her identity with two words: Squirrel Girl. The woman disappears, the myth emerges in her place.

***

Another search for Squirrel Girl via Beard takes me to The Autry Museum of the American West, in Los Angeles: the museum archive houses Beard's manuscripts and research papers. I am hopeful they can help me trace the history of this photograph and so I email them a request for help. But we are in the middle of a global pandemic and the archives are, understandably, closed. I don't expect to hear from them any time soon.

But, to my surprise, a week later I receive an email from a woman whose signature identifies her as "Head Research Services & Archives, Autry Museum of the American West." She is interested in helping me find out who Squirrel Girl is and, in the meantime, alerts me to a Twitter hashtag, #Archivingwomen, connected to the "Revealing Women in the Archives" project. I learn that this initiative examines "the connection between archival work and . . . our ability to tell women's stories." She writes that, once the archives are reopened, she will help me find out who Squirrel Girl is.

***

There is another photograph, a photograph that — like the image of Squirrel Girl — has transformed my relationship to storytelling and power and narrative and archives: a grainy photograph of the interior of an abandoned textile mill in Mumbai. I encountered it in a museum gallery while conducting ethnographic fieldwork in the coastal Indian city in 2008. It is sepia to indicate timelessness: sepia like Joanne's chosen family, like Squirrel Girl's mysterious glower. The winding machines look rusted; dust and debris are scattered everywhere. The windows are boarded up, only slivers of light can fight their way through cracks in the ramshackle wooden shutters. It is a disembodied image; it reflects the present but looks like the past. It is the visible, ruined side of the unseen but lively place I spent my morning observing.

When I encountered this photograph on that December day in 2008, I had just come from a morning at the textile mill at the center of my dissertation research: a functional textile mill in a city convinced there were no functional textile mills. I walked down the road on that sweltering afternoon, sweat snaking down between my shoulder blades, cotton particles clinging to my damp skin like smoke. I heard that the nonprofit, "Partners for Urban Knowledge, Action and Research," or PUKAR, recently opened an exhibit entitled "Girangaon — Kal, Aaj Aur Kal."

Girangaon — "the city of Mills." Kal, Aaj Aur Kal — "Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow." In Hindi, the words for "yesterday" and "tomorrow" are the same — Kal. It's the context of the word's use that places it in time.

The exhibit was a series of photographs, all in sepia or black and white, none in color. PUKAR's project involved providing the children of former textile mill workers with cameras and training them how to document their lives. The exhibit told me: "The Girangaon community has become a myth." But myths are about the past, about the imaginary. The mills were neither past nor imaginary: they were not gone.

This long-term ethnographic research project became my recent book, The Archive of Loss: Lively Ruination in Mill Land Mumbai. In the book, I investigate the connections between work and storytelling, also central to the #Archivingwomen project. I write about the remaining mills and industrial workers who struggle to exist in a seemingly postindustrial urban landscape. The city tells me the mills are no more. But the workers at a functional textile mill, which I call "Dhanraj Spinning and Weaving Ltd," show me that these spaces of "lively ruination" continue to exist, even as they have been replaced by a mythology of deindustrialization and finality, cleanly demarcated temporal shifts and a post-industrial present. Their identities have been replaced by images, their stories lost to more convenient histories.

I didn't understand this story until years after my research was complete. As I was writing the book in 2017, I remembered the day I encountered the PUKAR photographs, particularly the sepia image of the abandoned mill interior. This encounter could be seen as a series of accidents. I was in the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Mumbai City Museum, Mumbai's oldest museum. In one of the densest cities in the world, the museum is, conveniently, right down the road from Dhanraj, a ten-minute walk down the main thoroughfare of Ambedkar Road. Built in 1872, five years after my Texas time-traveling adventure, it is a museum of the city and it tells many stories of the city's past and present. And sometimes even its future.

In 2008, I did not yet realize, when I stood in that Mumbai museum and stared at the photograph of the Mumbai mill, I was inhabiting what I would later understand to be both the visible and the metaphorical museum gallery of the mill lands. I did not yet know that this Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Mumbai City Museum gallery would lead me to the metaphor I was searching for and so I didn't yet understand how Dhanraj, in contrast, was the archive of the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Mumbai City Museum gallery: what I would frame as the archive of loss. I didn't yet see — even as my informants at the textile mill continued to work down the street in Dhanraj, the metaphorical archive — how the museum of history was writing them out of existence.

As the relationship between the museum and the archive came into focus for me, I drew heavily on the language of China Mieville, whose novel, The City and The City, changed "invisible" to "unvisible" as a way of alerting his readers to how what we "see" and "do not see" is not accidental but instead learned, intentional. This, for me, was indicative of the archive. Who goes searching for traces and remainders and who instead stays rooted in the museum gallery, dazzled by the exhibits but uninterested in other truths? Other stories waiting to be told? Sometimes I see and hear those stories but more often I do not. I, too, have been taught to unsee and unhear most of the stories around me. But also: I am hungry for the real.

***

When I tell my friend Matt about the woman in the photograph, he directs me to the work of Diné photographer Will Wilson and his Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX) project. Wilson photographs the descendants of Edward Curtis's subjects, but in ways that "generate new forms of authority and autonomy" through the negotiation of photographic exchange: the encounter becomes a ceremony. In this way, both photographer and subject re-inscribe and re-imagine Indigenous futures, beyond the exoticizing and stagnated vision of Curtis's work. I study Wilson's archive of images, catalogued on his website. I look through the faces of the women he has photographed, wondering if any of them are retelling the story that the woman in my postcard-photograph lost when Beard catalogued her image and renamed her Squirrel Girl.

***

I never thought to look into who the people making up Joanne's chosen photographic family were, and whether they might have somehow been related to me. I let them become decoration, background, wallpaper. Those images were never people to me. But if I had chosen to imagine their lives, if I had chosen to enliven that archive, I could have drawn on Saidiya Hartman's speculative methodology, I could have imagined the lives they lived, so similar to those of my own ancestors, who travelled from Russia and Romania to the United States at the end of the nineteenth century, moving through Ellis Island and into New York City. I know that story, I am of that story. My historical imagination has been forged by that story.

Can I do the same with Squirrel Girl? Over the past one hundred years, my Jewish immigrant roots have been whitened and now my historical imagination is steeped in violence, White Supremacy, and settler colonial genocide. What would it mean for me to imagine the life of the woman who became Squirrel Girl? Is there any possibility for such imaginings to be anything other than further projects of erasure? Perhaps by discovering the woman behind the image, I am hoping to redeem not only the woman I am searching for, but myself, as well. I struggle to resist this drive. This redemption story does not belong to me. To pretend otherwise would simply be to replicate the violence that stole her story in the first place.

***

For now, I am left with an incomplete story, there is no conclusion to be wrestled with here. The pandemic has stalled my ability to follow her trail, where realizations and resolutions may lie in wait for me. Or not. An archive is a collection of possibilities, a space of evidence, an accumulation of information, of artifacts, of answers. But it is also a black hole, a place of erasure. And now my access to the archive, a space where Squirrel Girl's story may or may not reside, is blocked by requisite COVID-driven closures.

This ending is a quintessential American story. Archives belong to a violent architecture of knowledge and are infused with the same ordering and purification narratives as Indigenous genocide, the transatlantic slave trade, and the plantation system. Knowledge production is not simply about visibility and recovery, it is also about denying presence and of erasing certain stories. The woman who became Squirrel Girl was erased when she lost her name and erased when her image was separated from her story. But I take some comfort from Barthes, who tells me:

From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here; the duration of the transmission is insignificant; the photograph of the missing being, as Sontag says, will touch me like the delayed rays of a star.4

I think I finally feel this radiation: these rays are a reckoning. Perhaps, when the pandemic recedes and the archives reopen, I will follow the faint trail this woman has left for me. Perhaps I will follow her delayed rays into the archive, where her name and her story can be retrieved. But I also know that it is more likely I have reached the end of my search, that this is as far as her trail will take me. She doesn't owe me her story, she doesn't owe me her name. And I am not the one who can reimagine a future for her. But perhaps she has taught me that, if I am willing to reckon with my own limitations, I can also begin to pay my own debts.

Maura Finkelstein (@Dr_mauraf) is an assistant professor of anthropology at Muhlenberg College. Her first book, The Archive of Loss: Lively Ruination in Mill Land Mumbai was published by Duke University Press (2019). She is currently working on an ethnography about therapeutic horseback riding, disability, and interspecies communication. Follow her on Instagram dr_mauraf — her writing can be found at maurafinkelstein.com.

References

- While there is currently a debate over whether or not to capitalize "White," I have decided to do so following the Sociologist and poet, Eve L. Ewing, who, in explaining why she has chosen to capitalize White, writes: "When we ignore the specificity and significance of Whiteness — the things that it is, the things that it does — we contribute to its seeming neutrality and thereby grant it power to maintain its invisibility. Please see "I'm a Black Scholar Who Studies Race. Here's Why I Capitalize 'White.'" In Zora, July 2, 2020.[⤒]

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981): 87.[⤒]

- The same is true of Pennsylvania, the state where I now reside.[⤒]

- Barthes, 80-81. [⤒]