Issue 7: Post45 x Journal of Cultural Analytics

Writing in 1981, Ron Silliman could not have been more astute in characterizing networks and scenes as the two governing modes of social organization in postwar American poetry.1 According to Silliman,

the social organization of contemporary poetry occurs in two primary structures: the network and the scene. The scene is specific to a place. A network, by definition, is transgeographic. Neither mode ever exists in a pure form. Networks typically involve scene subgroupings, while many scenes (although not all) build toward network formations. Individuals may, and often do, belong to more than one of these informal organizations at a time. Both types are essentially fluid and fragile. As the Black Mountain poets and others have demonstrated, it is possible for literary tendencies to move through both models at different stages in their development. (Silliman's italics)2

From the New American Poetry to New Formalism, publishing networks such as literary magazines and social scenes such as poetry reading series have served as the foundational structures of poetic schools and movements. These two discrete modalities of interaction and exchange in literary communities give us a capacious model for understanding the varied poetic formations in the postwar period. Silliman additionally argues that networks and scenes compete with each other to compose a "dominant or hegemonic formation," and that access to these organizing structures of poetry communities may shape a poet's career, whose "major components include monetary rewards, prestige (often called influence), and the capacity to have one's work permanently in print and being taught."3 In other words, poetic movements are often successful if they are organized through print networks and/or social scenes.

More recently, as audio archives of poetry readings have been digitized in large volumes, Charles Bernstein, codirector of PennSound, has provocatively identified the novel modes of organization these archives offer:

I believe that access to compressed sound files of individual poems, freely available via the internet, offers an intriguing and powerful alternative to the book format in collecting a poet's work and to anthology and magazine formats in organizing constellations of poems. Imagine for a moment that you had on the hard drive of your computer a score of MP3 files of poems by 50 of your favorite twentieth-century poets. I would bet that no matter how involved or committed any of you may be to twentieth-century poetry, none of you have such a collection readily available. But in poetry's coming digital present you will, or anyway, you easily might. What would be the implications of such a collection?4

Open access to these digital archives certainly allows readers of American poetry to create a mixtape of their choosing. Furthermore, a digital archive of poetry readings is a new medium of distribution, and, in fact, it "offers an intriguing and powerful alternative" to organizing practices such as networks and scenes. One instantiation of the novel possibilities afforded by such digital archives is PennSound, a collection of readings, talks, interviews, and so on, which are curated from different reading series. Such recordings were made at multiple locations, so the archive does not constitute a scene in the strictly geographical sense. Instead, it represents many avant-garde poets from disparate movements, presenting them in a common digital space. As PennSound organizes the postwar period in a different combination, it (re)configures poetic communities by adding new structures of affiliation and alliances among these poets.

Recent scholarship in audio research and American poetry has produced important bodies of criticism that address the poetics of audio-based composition or the hermeneutics of public performances.5 However, these studies are often limited to individual authors, specific time periods, or momentous events. Since various institutions have made their entire archives of poetry recordings digitally available, we are poised to use digital methods to analyze how they represent the period at a diachronic scale. As Marit J. MacArthur, Georgia Zellou, and Lee M. Miller have demonstrated in their study, titled "Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets," computational methods can be used over large corpora of poetry recordings to analyze linguistic features, classify poetic styles, and assess the influence of emergent cultural factors such as professionalization in the public performance of poetry.6 While process and performance are topics of continuing interest in audio research, we are motivated by slightly different, yet equally fundamental questions: Who and what are represented in these archives? How do these archives compare to the canons of coherent textual communities?7

Combining Bernstein's definition of the digital audio archive with Silliman's understanding of poetic community gives us a composite vision of organizing principles in postwar American poetry. We take seriously their invocation of poetry reading venues as well as audio archives — alongside more familiar print networks constituted by poetry anthologies and magazines — as important and distinct sites of reception for American poetry. We use network analysis to literalize Silliman's notion of poetic networks and to visualize the relationships of individual poets to venues where they have read, archives where their readings are stored, and text anthologies where their poetry has been printed. Examining several types of poetic archives allows us to apprehend the relationships between poets and their "networks and scenes," understood both in terms of print and audio culture, as well as trends and changes in the formation of these poetic communities and affiliations. As Silliman and Bernstein suggest, this approach may offer new ways of imagining the multiple dimensions contributing to the social formation of contemporary American poetry.

Central to our study is the gradually evolving interdependence between profession and practice, and in this analysis, we will show how the formation of poetic communities has shifted substantially over the course of the late twentieth century, with the increasing prominence of MFA/PhD programs in creative writing — the so-called "Program Era" — and the correlative rise of poetry reading culture. According to Loren Glass, "postwar poetry, in particular, has been neglected as a product of the Program Era, even though it is, arguably, a purer example, since poets now depend almost entirely on the patronage of the university."8 In fact, literary histories of geographically delimited poetry scenes of the postwar period are often expansive accounts of avant-garde and counterculture communities.9 In order to locate the varying emergent stages of the Program Era, often referred to as the "mainstream" poetic practice and contrasted with avant-garde formations, we compare PennSound's avant-garde collection with the audio archives at universities where graduate writing degrees are offered. We created networks of these poets by systematically processing the bibliographies of the digital audio archives of poetry readings housed at three different universities: the Elliston Project at the University of Cincinnati; PennSound at the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing; and Voca, a digital library at the University of Arizona's Poetry Center.10

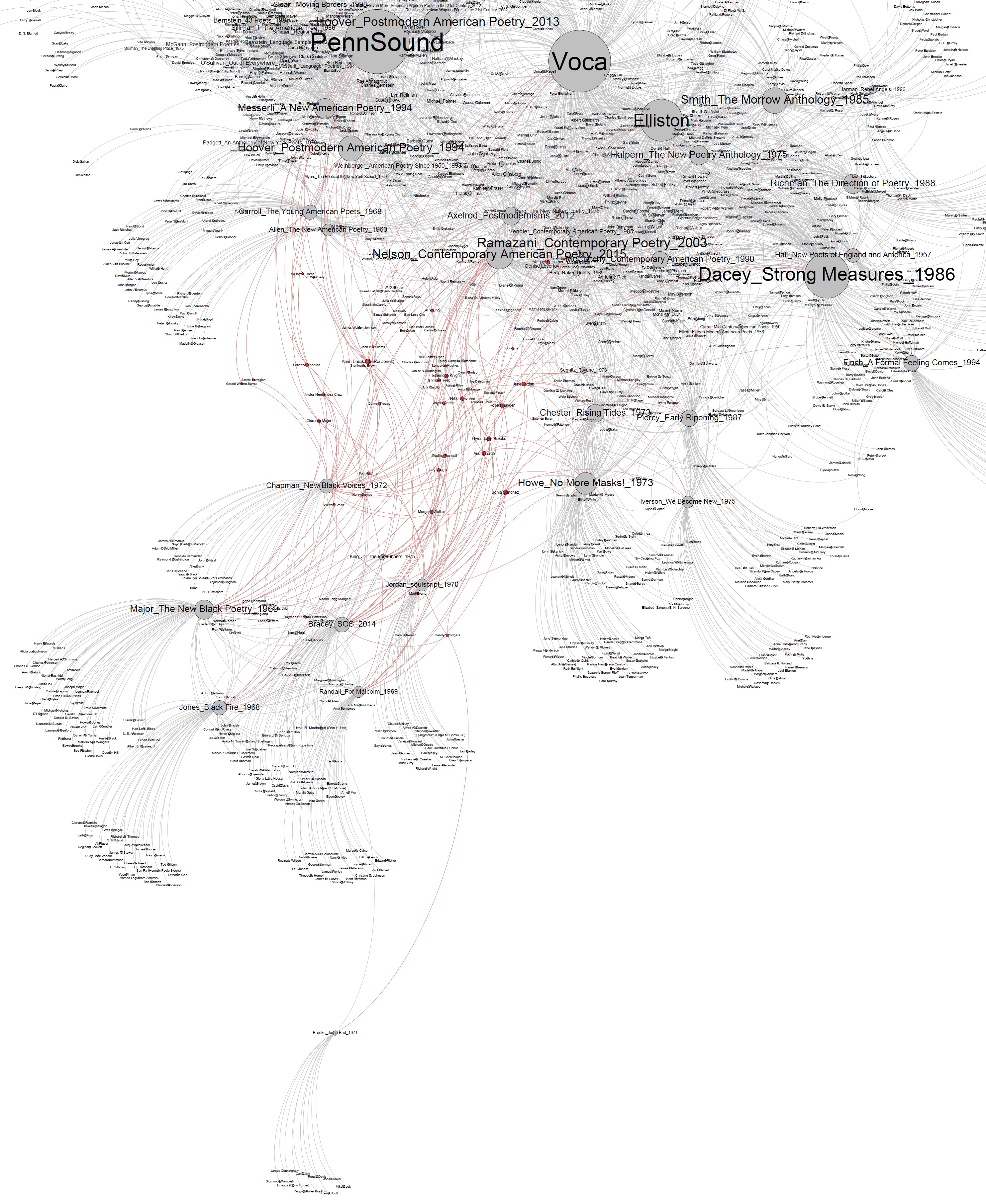

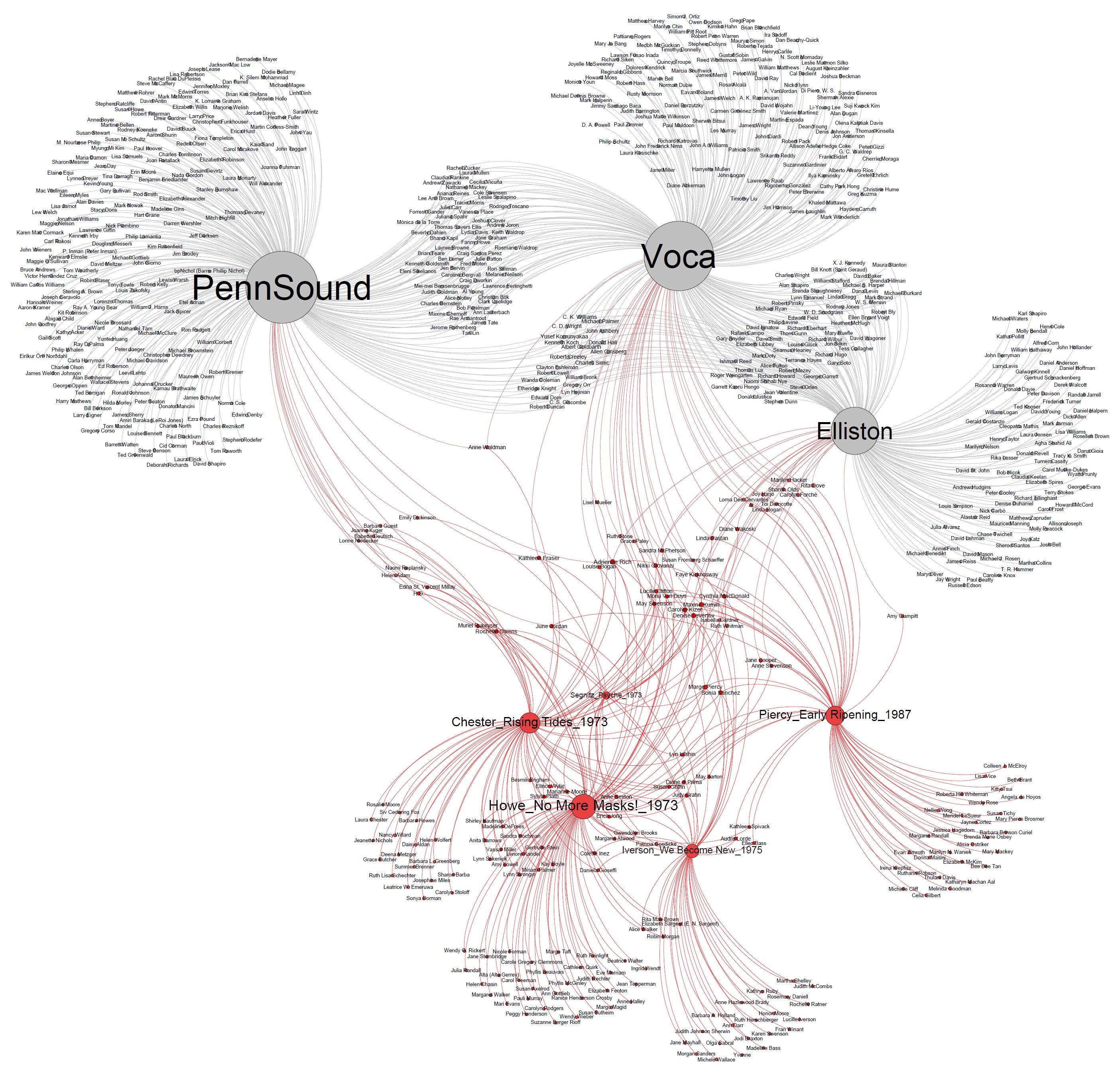

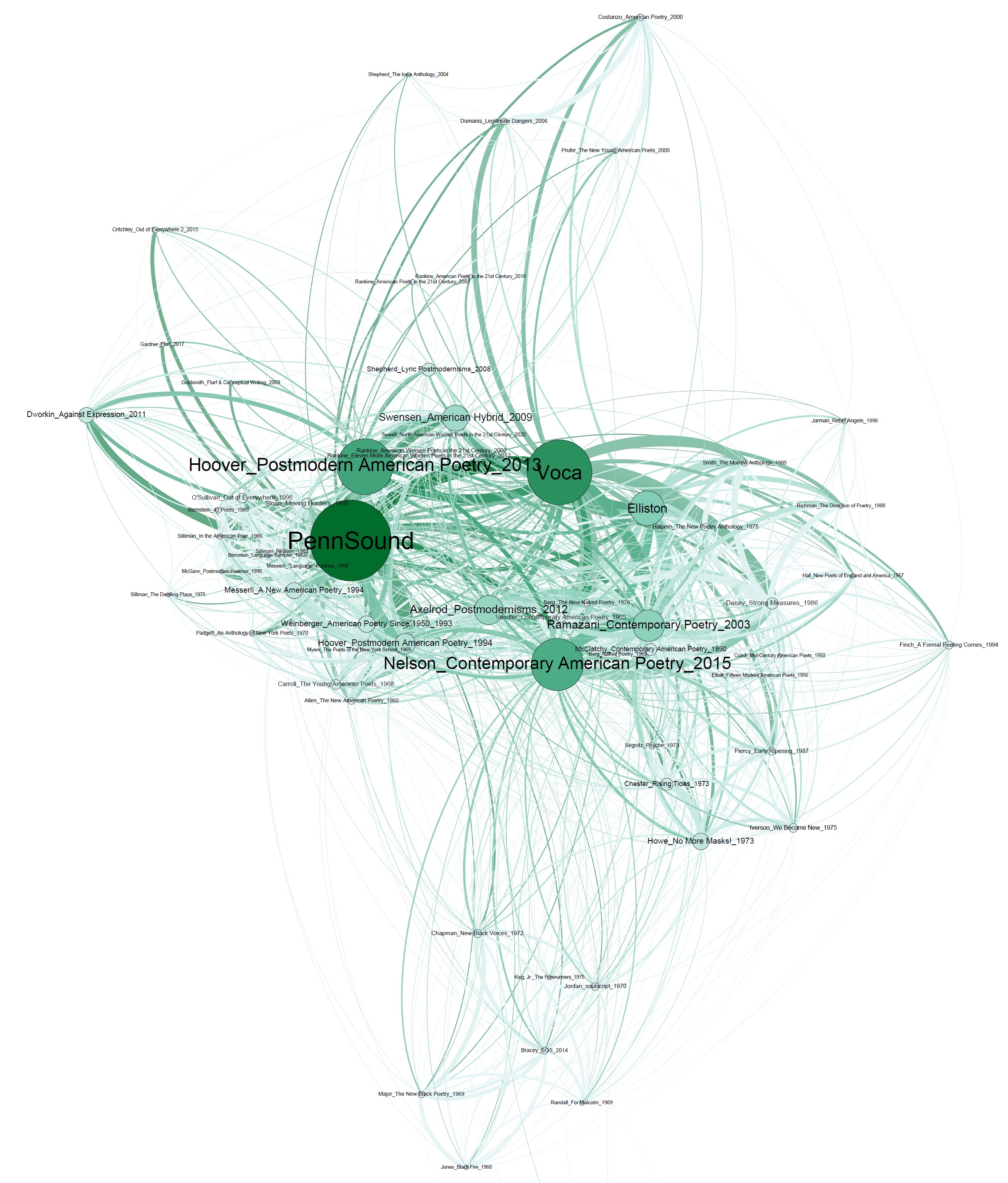

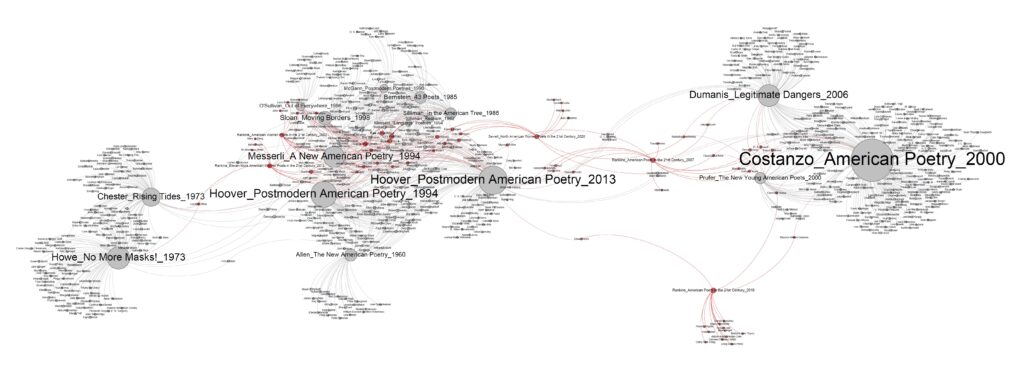

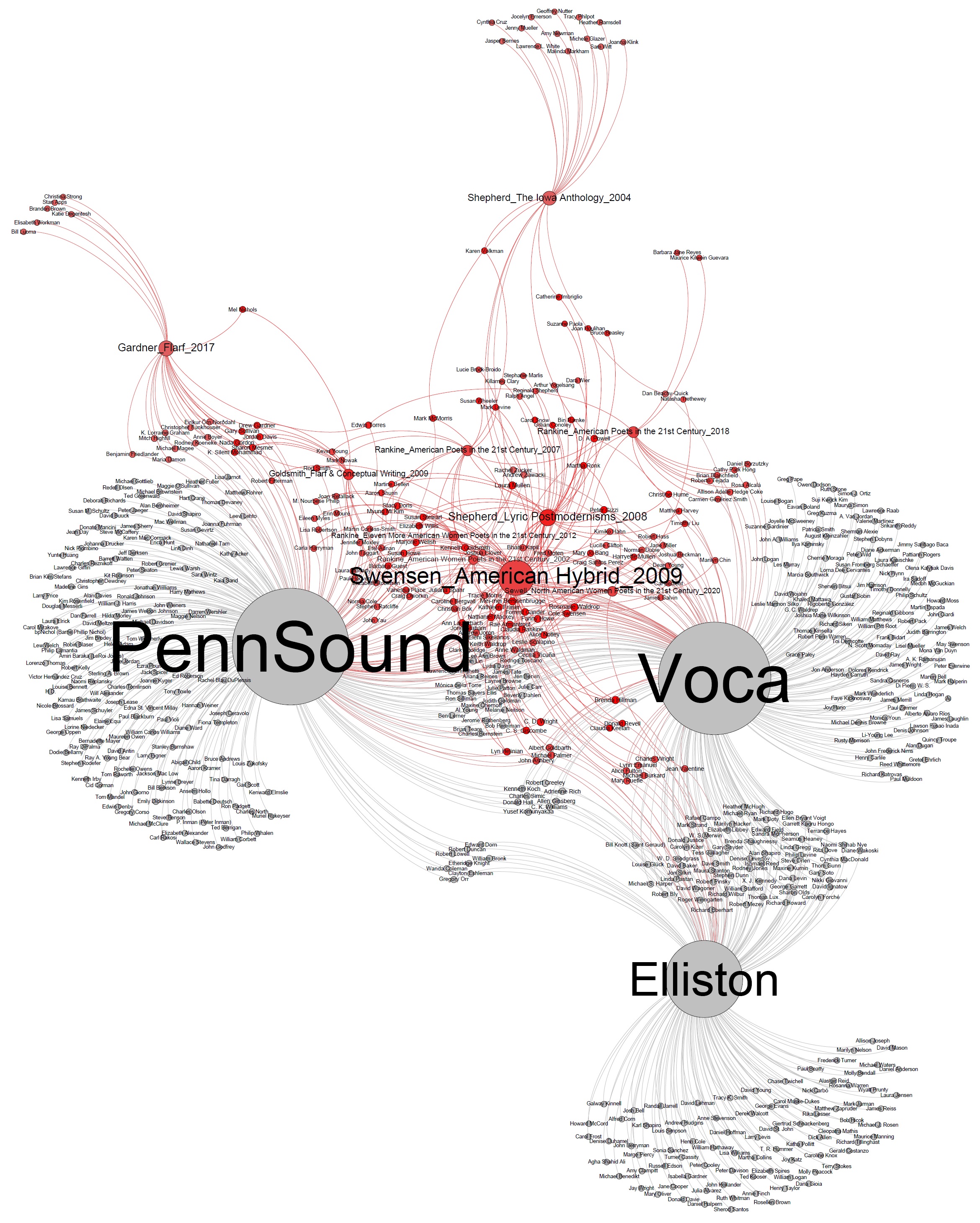

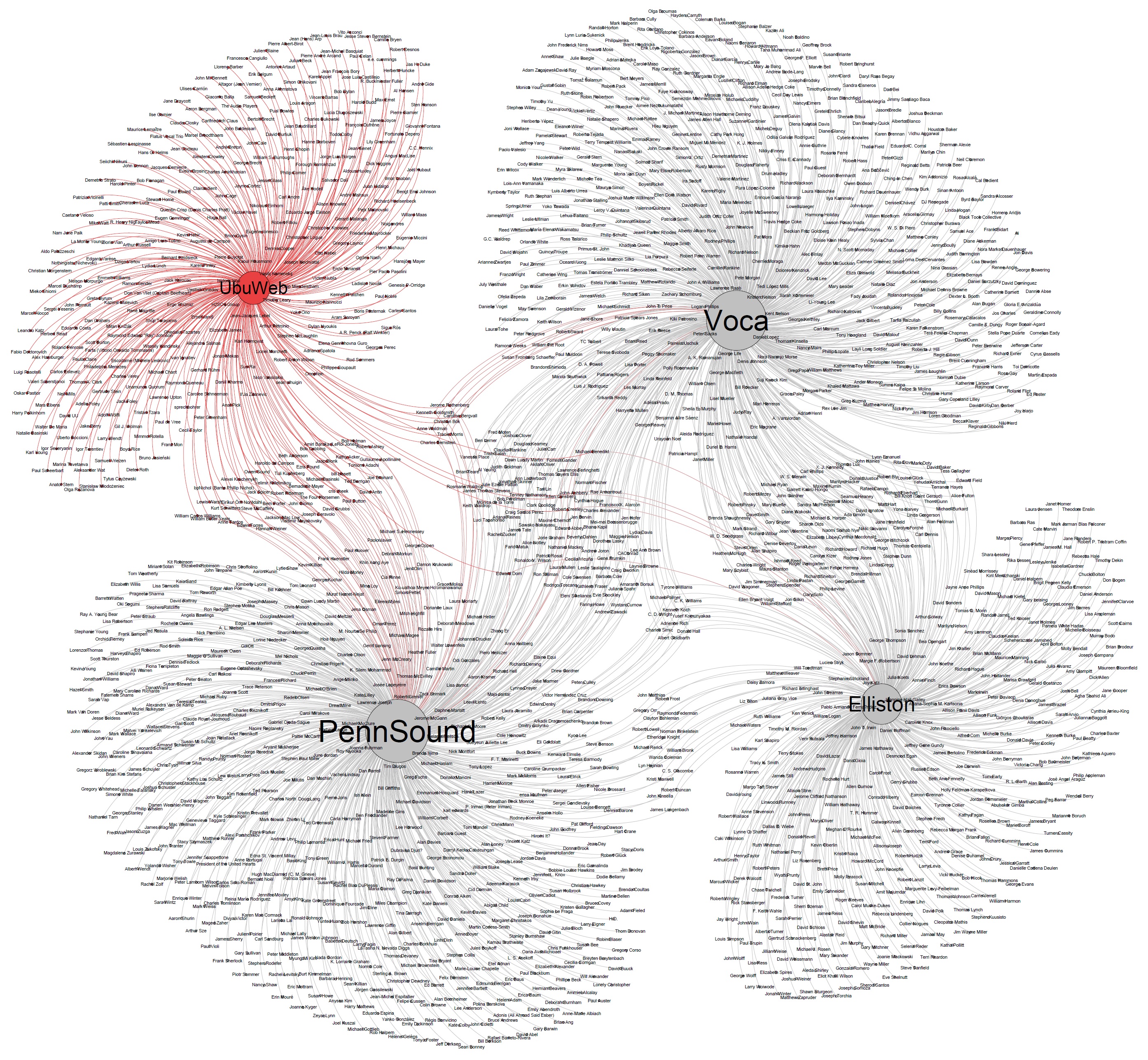

Even in a simple network graph like this, where edges/ties refer to the connection between poets (smaller nodes) and audio archives (larger nodes), we can see three different groupings (figure 1). A large number of poets are represented in only one audio archive in a hub-and-spoke fashion. A small number of canonical poets are at the center of the graph because they are represented in all three archives. A significant portion of poets with overlapping representation in two archives are positioned between these archives. According to the network diagram, poets represented in Voca are likely to be represented in Elliston and PennSound; however, Elliston and PennSound represent different groups of poets. At this point, we are tempted to infer that PennSound is rigidly affiliated with the avant-garde poets, that Elliston is affiliated with the Program Era poets, and that Voca's affiliation lies somewhere in the middle.

Our study is limited to Elliston, PennSound, and Voca because these are the largest archives of poetry recordings that are fully available in digital forms. (We will look at another digital archive, UbuWeb, at the end of this essay.) The Elliston and Voca archives allow us to systematically infer how the "scenes" undergirding poetic movements were formed at university-sponsored reading series. Although Elliston and Voca are collections of on-campus poetry readings, they do not represent scenes because the readings often take place on different days, so these reading series rarely facilitate interaction among the poets represented in these archives. Does this mean that Elliston and Voca also represent poets who were not part of a poetry scene? Elliston and Voca are good test cases because the universities that sponsored these poetry readings saw a transition in their English Departments during the time when the graduate creative writing programs, one of the primary institutional manifestations of the Program Era, were rapidly increasing in number nationwide.11 The MA/PhD program in creative writing was established in 1978 at the University of Cincinnati, and the MFA program was established in 1972 at the University of Arizona. Elliston and Voca are subtle registers of historical changes in the postwar period, including the emergence of the Program Era as a hegemonic poetic formation. We juxtapose twenty-first century avant-garde practices like PennSound with digital reproductions of these scenes at university campuses to show how these reading series mediated poetic reception and how these audio archives continue to do so retrospectively.

We approach this dataset through social network analysis and visualization to distribute these poets into a network diagram of audio archives, and we measure this underlying structure of representation alongside another variable of representation: publication in anthologies of the postwar period. These audio archives aggregate representatives from different poetic circles and they are similar to poetry anthologies in the sense that both of them distribute delimited canon(s) of the period. To build our networks, we used the network analysis tool Gephi to visualize the relationships among several levels of analysis that are typically considered separate objects of study.12 The resulting multi-entity network traces the relationships among nodes defined as individual poets, anthologies in which their works are printed, and audio archives (representing a reading venue in the case of Elliston and Voca) that house their poetry readings. Creating a network with these two scales of analysis — individual poets and the anthologies and audio archives in which their work is present — allows us to see at a single glance higher order structures of poetic community and affiliation as well as the more fine-grained pictures of individual contributors to these communities.

Our project builds upon Richard Jean So and Hoyt Long's "Network Analysis and the Sociology of Modernism," where they argue that poetry magazines mediated the formation of poetic schools in the high modernist period through networks of publication. Little magazines acted as centers of poetic activity during the rise of professionalization, and, according to So and Long, "in general, one's identity as a poet in these settings could be as much about one's own self-defined style as it was about the journals in which one published and thus also the poetic circles or schools to which one could claim an affiliation."13 So and Long argue that with "techniques borrowed from the fields of social network analysis and relational sociology," we get "new ways of interrogating the collaborative networks that underwrote the evolution of modernist poetry globally."14 Throughout the twentieth-century, literary magazines have afforded collective identities within poetic groups, and a diagrammatic method that relies on simple techniques such as creating nodes and edges allows us to create networks of entire historical periods that would have been unimaginable without digital technology.

At this point, however, literary magazines of the postwar period are out of our scope of study. Instead, we compare an audio archive's canonizing structure with that of anthologies to identify the poetic groups represented through these poetry readings as well as to determine their contribution to the networks of the postwar period. Anthologies structure poetic groups, form alliances out of specific interests, and configure the canon(s) in a given historical period. As Jeremy Braddock argues, modernist anthologies sought "to determine the constituents of the movement, group, or field, in gestures that were by turns restrictive (because of the constitutive selectivity and exclusions of a given collection) and synthetic and enabling (where the collection's disparate pieces represent a new, hitherto unimagined form of sociability and set of affiliations)."15 These modernist anthologies were transformative practices because "the contest for modernism's social definition took place within this field of collections."16

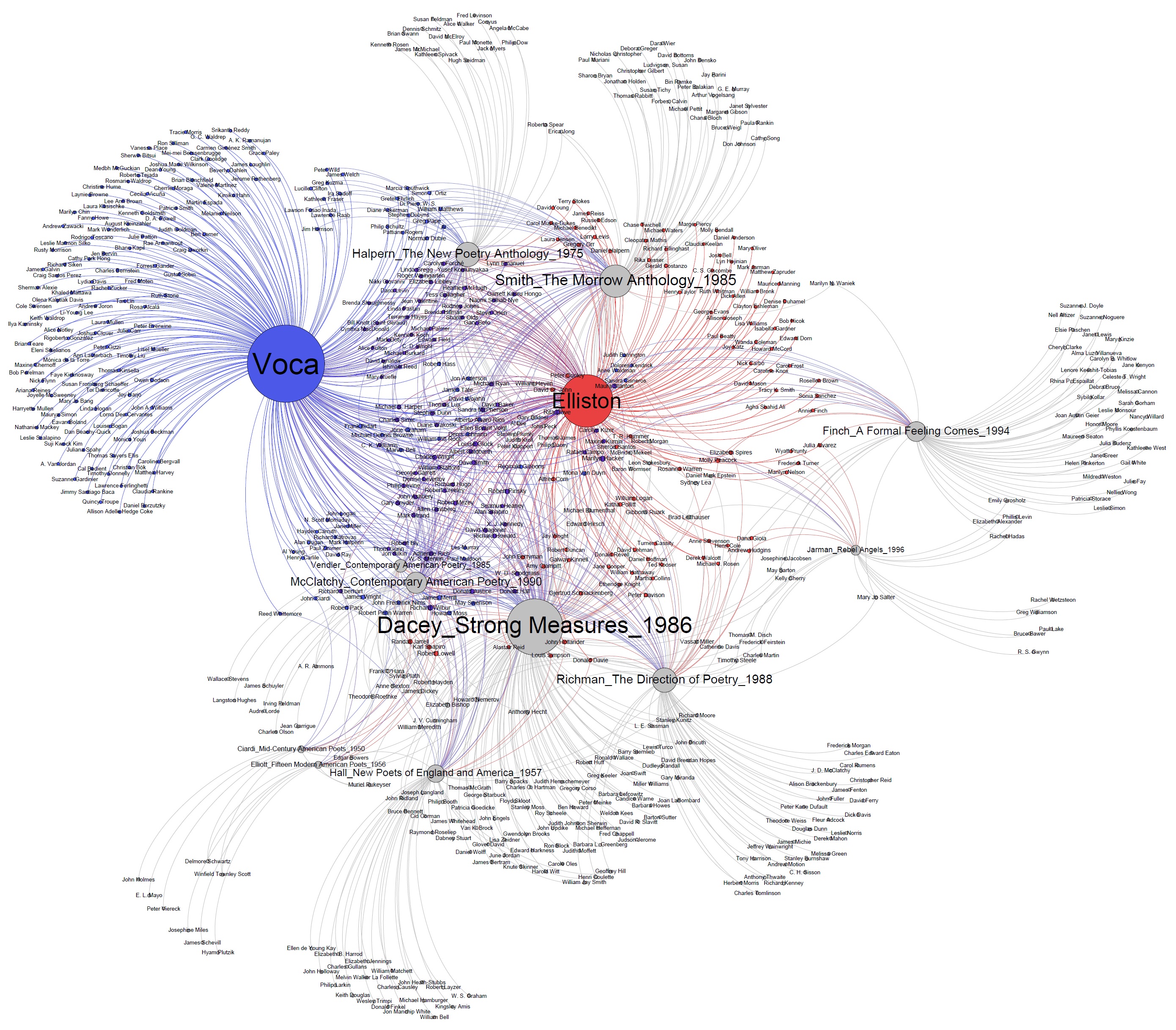

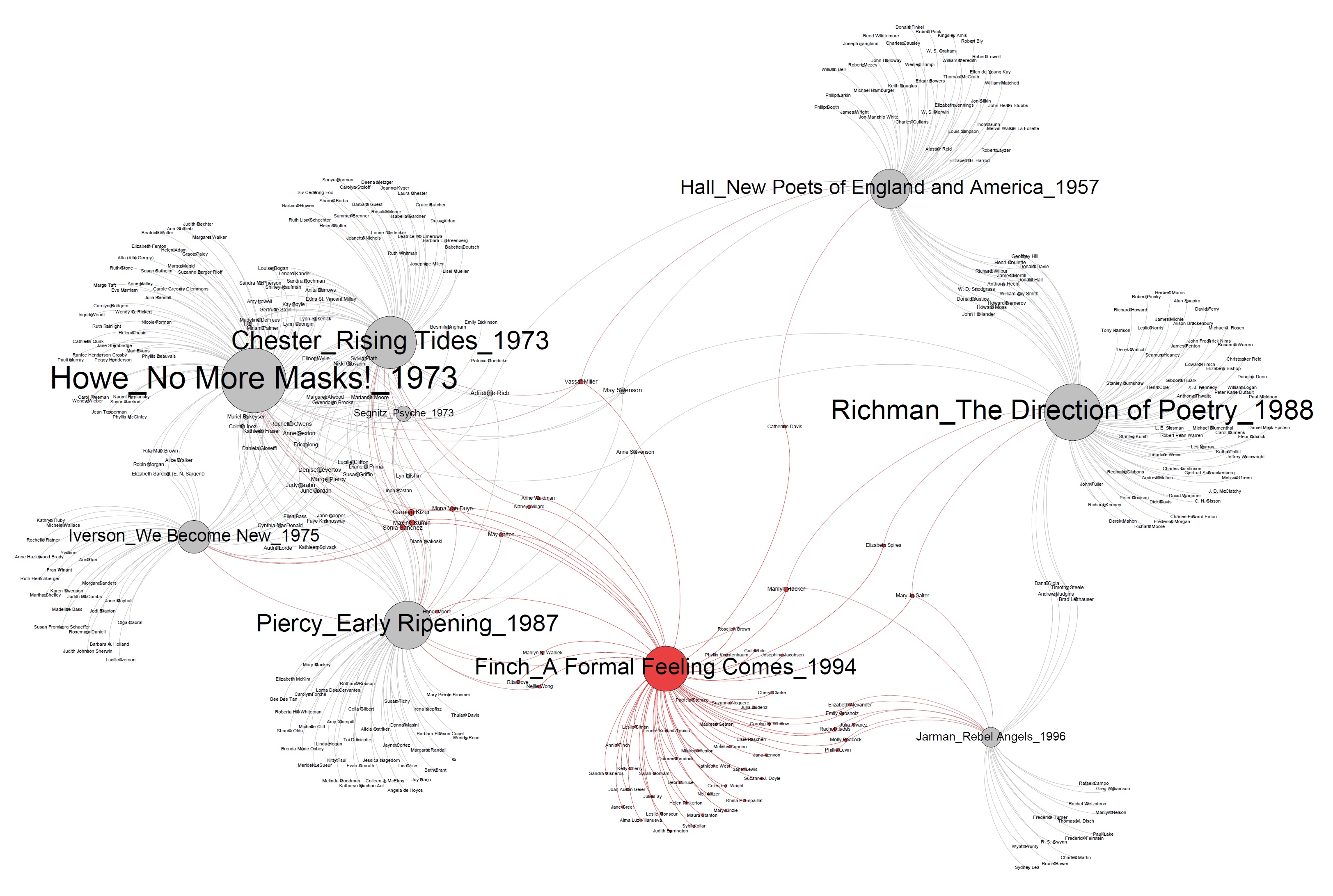

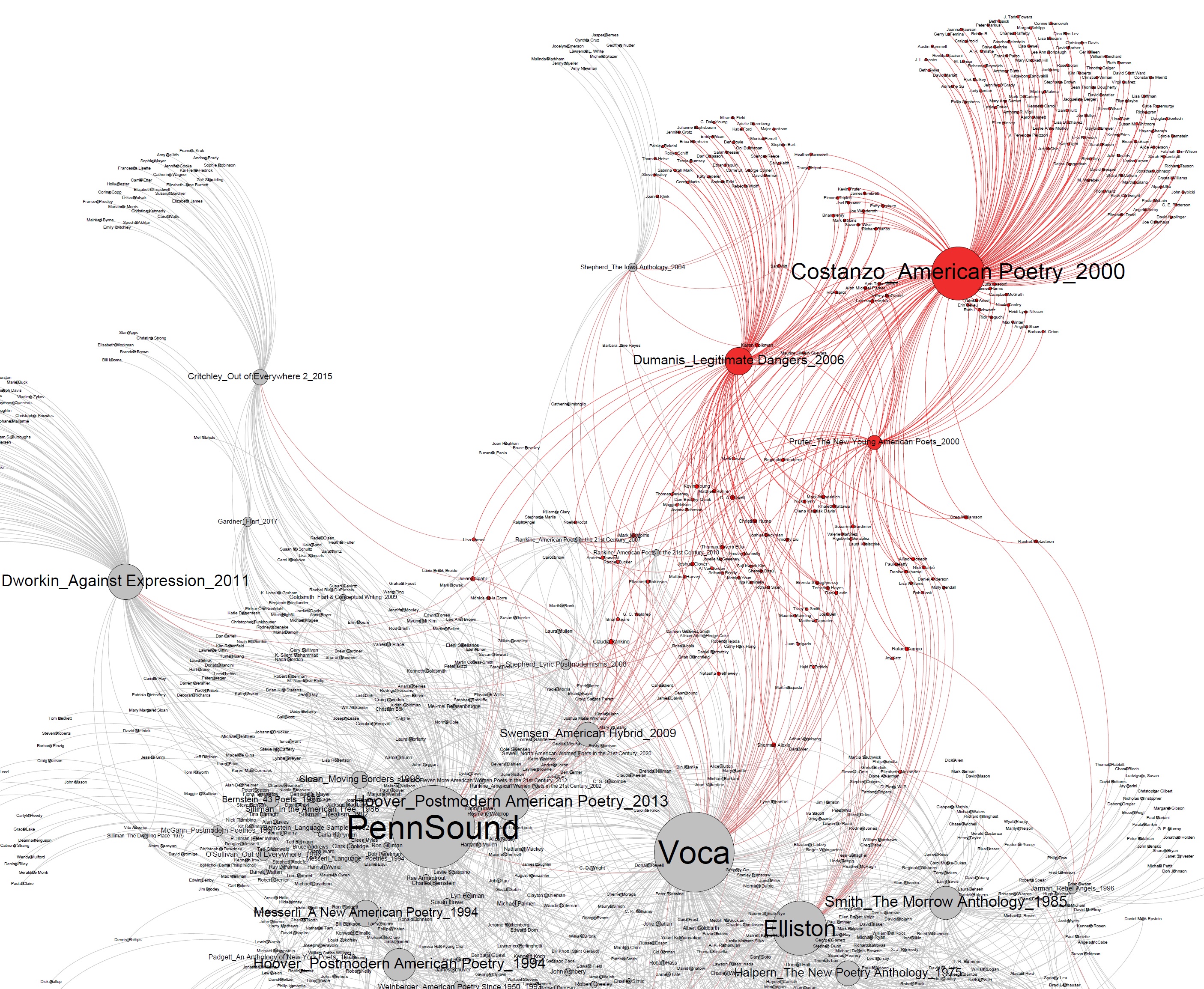

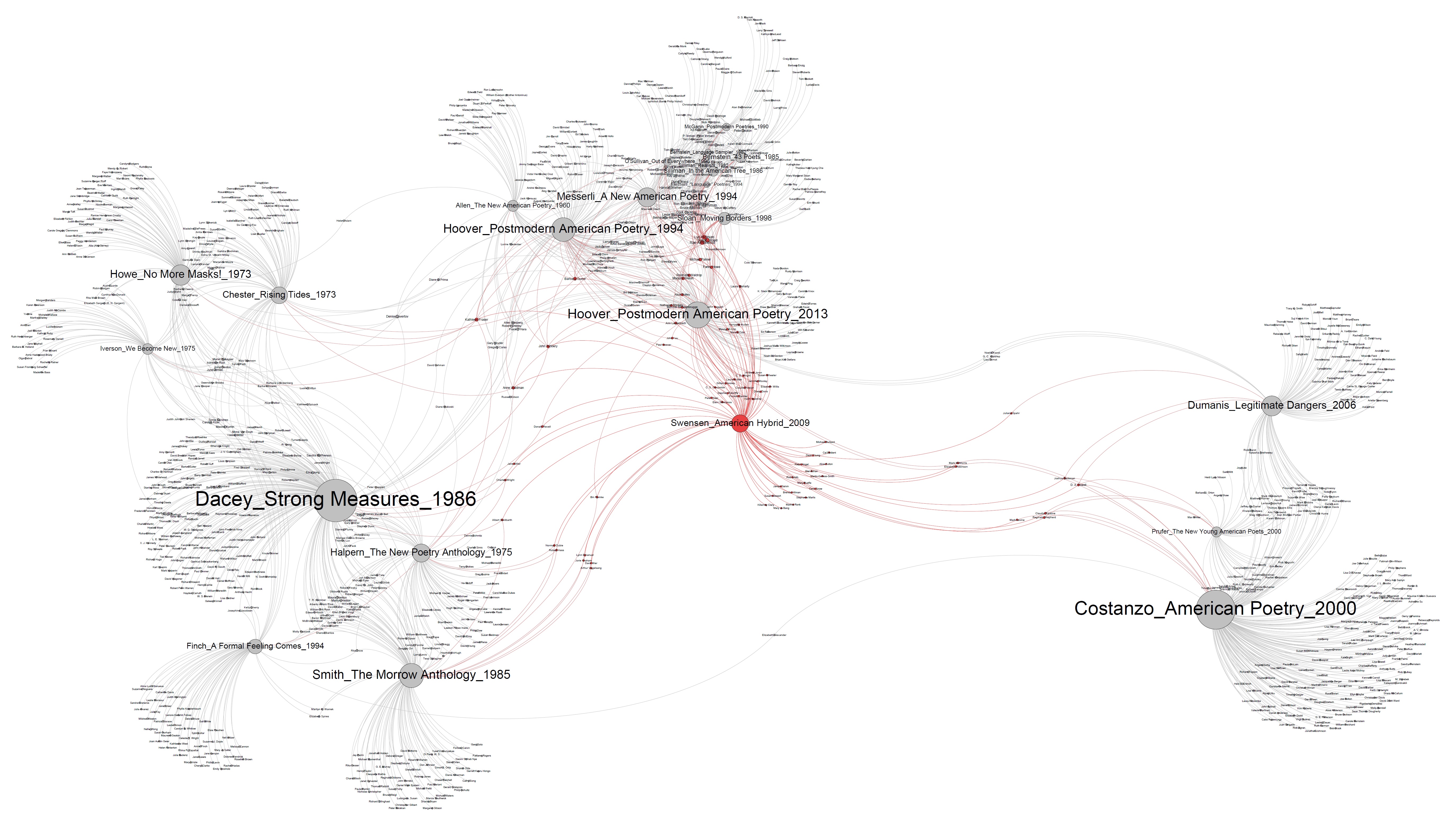

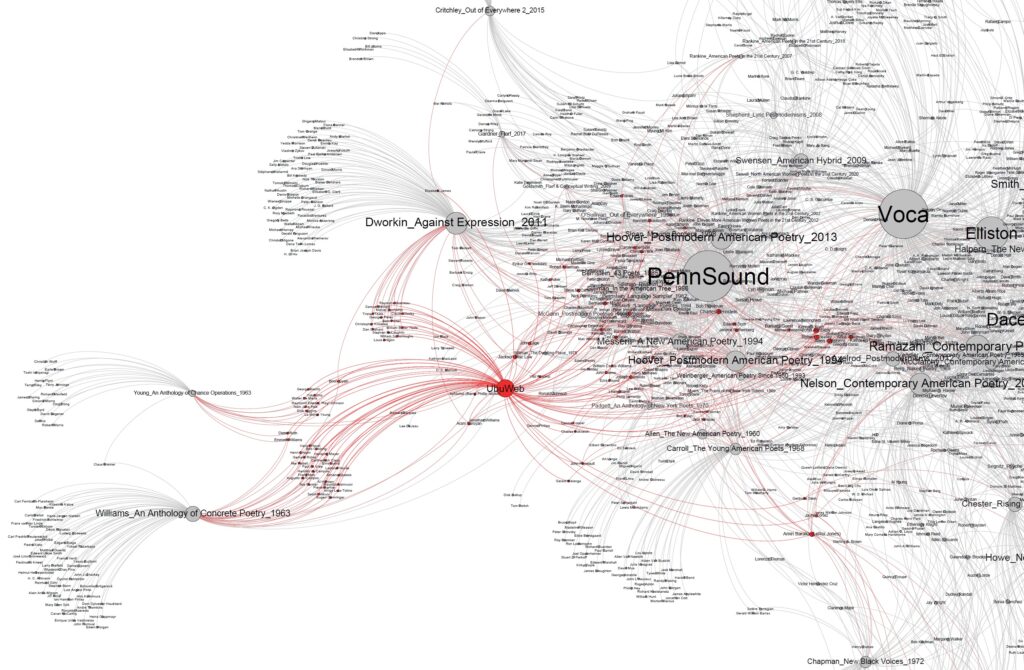

Our collaborative network comprises the three aforementioned audio archives and the following three types of anthologies (figure 2).17 First is the group of "aesthetic" and "identity-based" "revisionist anthology[ies] designed to increase awareness of particular noncanonical poetry."18 These anthologies comprise three sections in our graph: the dense postmodern network (orange module) of avant-garde and innovative poetry anthologies appearing under the labels New American poetry and Language Writing, including the sequels of the New York School; anthologies associated with the Black Arts Movement (yellow module) and the feminist poetry movement (light blue module); and the loosely interlinked neo-/New Formalist anthologies (dark blue module). The second group comprises textbook/teaching anthologies used in classrooms and surveys of contemporary poetry (purple module). The third group is anthologies of emergent poets (green module), which most often collect graduates of creative writing programs.19 The difference between the three audio archives, indicated by their red nodes, which was barely perceptible in the isolated diagram, becomes apparent in the collaborative network. We begin to notice the affinities of these audio archives: PennSound and Voca are close to the postmodern cluster, and Elliston and Voca are close to the New Formalism cluster. Another noticeable difference is their closeness to the Program Era anthologies, relative to their distance from the identity-based movements at the bottom. In this paper, we will use various diagramming techniques such as shading and partitioning to present information about the poetic groups and to analyze the organization in anthologies/archives that define the postwar period. Before we look at these organizing practices in our contemporary moment, we will begin by looking at how anthologies and audio archives collaborate in periodizing postwar American poetry.

Dense and Loose Networks of Aesthetic Movements

Although our network diagram shows a high degree of interconnectivity among the densely clustered poetic movements of the last seventy years, poetic communities in the beginning decades of the period were divided into two separate factions during the "anthology wars" of the 1950s (figure 3). We can see the separation between the two aesthetic camps, the avant-garde (red module) and the mainstream (blue module) in the distance between Donald Allen's The New American Poetry (1960) and three other anthologies published in the 1950s: John Ciardi's Mid-Century American Poets (1950), George P. Elliott's Fifteen Modern American Poets (1956), and Donald Hall, Robert Pack, and Louis Simpson's New Poets of England and America (1957).20 Various scholars have contextualized the anthology wars as ensuing from the academy's increasing role in the canonization of postwar poetry. Allen's The New American poetry was a response to "the widespread institutionalization — or academicizing of 'creative writing,'"21 and it was also a response to New Criticism's "dominant poetic discourse" of "self-contained, coherent, and unified" lyric poem.22 Because anthologies from the 1950s were incrementally repurposed for college classrooms,23 Allen, in fact, defined the New American poetry as "a total rejection of all those qualities typical of academic verse."24

Furthermore, we must note here that The New American Poetry was also a promotion of emergent postwar poets, "a strong third generation" in Allen's term, and it has remained the single most dominant collection of postwar poetry precisely because it appeared as a highly structured combination of network and scenes. 25 As Lisa Marie Chinn, Brian Croxall, and Rebecca Sutton Koeser demonstrate in their study, Networking the New American Poetry, Allen's select group of poets come from diverse textual communities of postwar literary magazines, and "the shape of the communities" in these magazines "suggests a network both less regimented and more capacious than Allen's anthology indicates." The poetic schools in Allen's grouping "were in practice quite permeable, as with the 5th Group and the Beats; and at times his groups are incoherent, as with the San Francisco Renaissance and the New York School."26 In other words, in order to counter the hegemony of mid-century anthologies, Allen organized his schools as network-scene assemblages. The social ties among members in these groups ranged from networks of co-publication and correspondence to scenes of poetry readings, affiliations with schools, and urban coteries, not to mention the self-theorization that appears as statements of poetics in the anthology.27

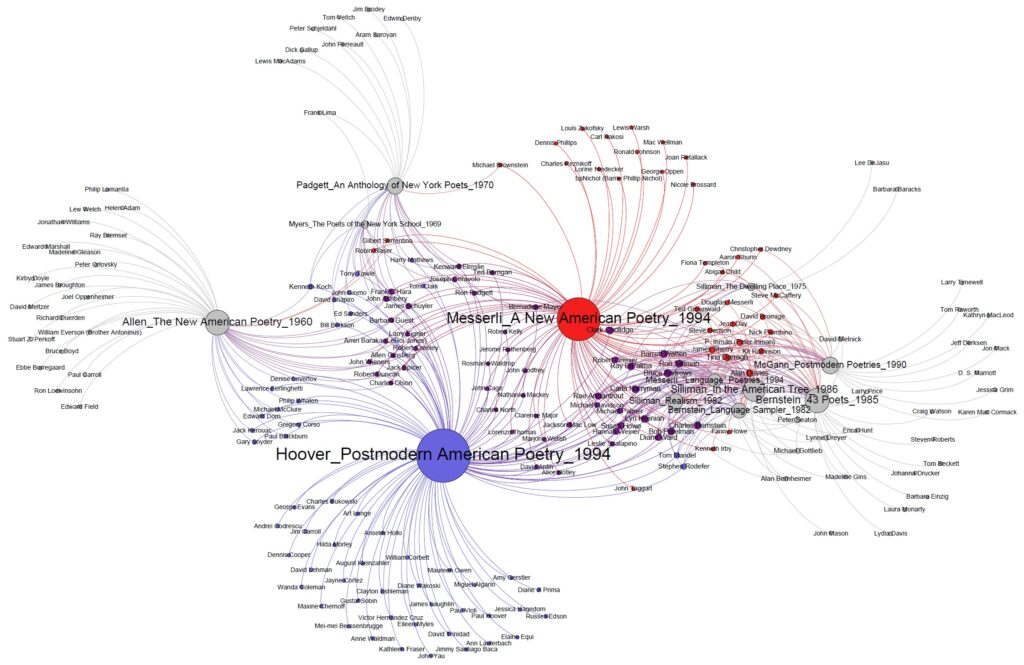

Revisionist anthologies like Allen's The New American Poetry consolidate the movement by grouping a new generation as part of an emergent formation, and the coherent textual communities in these dominant collections are often combined products of networks and scenes. The anthologies of Language Writing, another dominant aesthetic movement in postwar American poetry, intensifies this combination of networks and scenes even more than we see in the New American poetry. Beginning with Ron Silliman's mini-anthology of 1975, The Dwelling Place: 9 Poets, where Silliman referred to the formation as "not a group but a tendency in the work of many,"28 and ending as an emergent formation of the period nominally in Jerome McGann's anthology of 1990, Postmodern Poetries: An Anthology of Language Poets from North America and the United Kingdom, the seven anthologies of Language Writing form a tight cluster (figure 4).29

This is an example of closure, where every anthology is connected to each other, and removing any single anthology will not affect the connectedness of any pair of nodes. Before we turn to how these anthologies established an interconnected network and the role of PennSound in such a network, we should explain what social network theory has to say about the function of closure in network formations. As So and Long have explained, achieving closure in a network formation is important because it "enables intimacy and trust between the members of a group, and the further strengthening of bonds between group members." Closure is a positive attribute for the group as well as its members because "a closed social network allows one to build one's reputation precisely among such an intimate group of known peers and colleagues. One's accomplishment are better understood and appreciated within such close bonds, and from this, one earn one's reputation." Closure is extremely helpful for emergent groups because it "gives one the necessary sense of security and confidence to reach out to other groups."30 Because it is useful to align one's own interests with that of the group, achieving closure is a necessary strategy if the organization is to succeed as a coherent group.

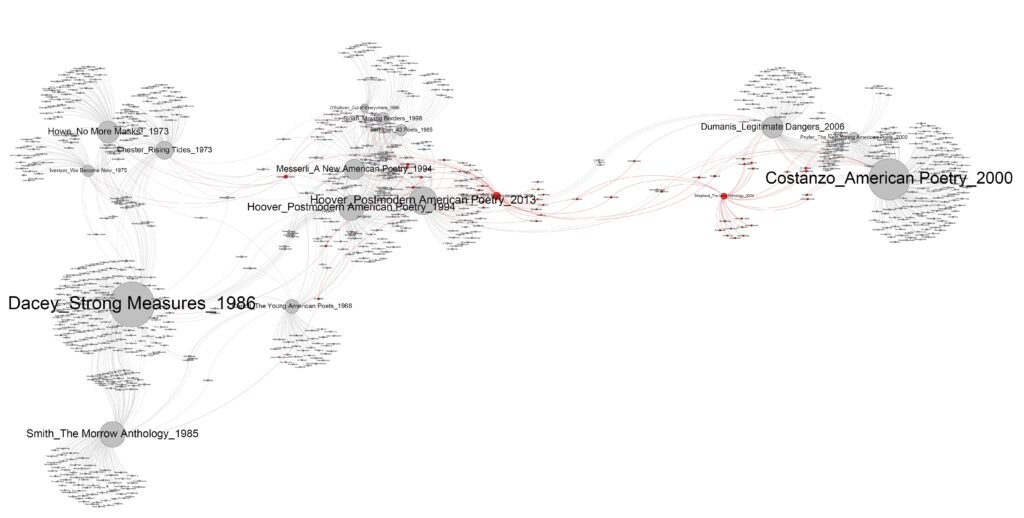

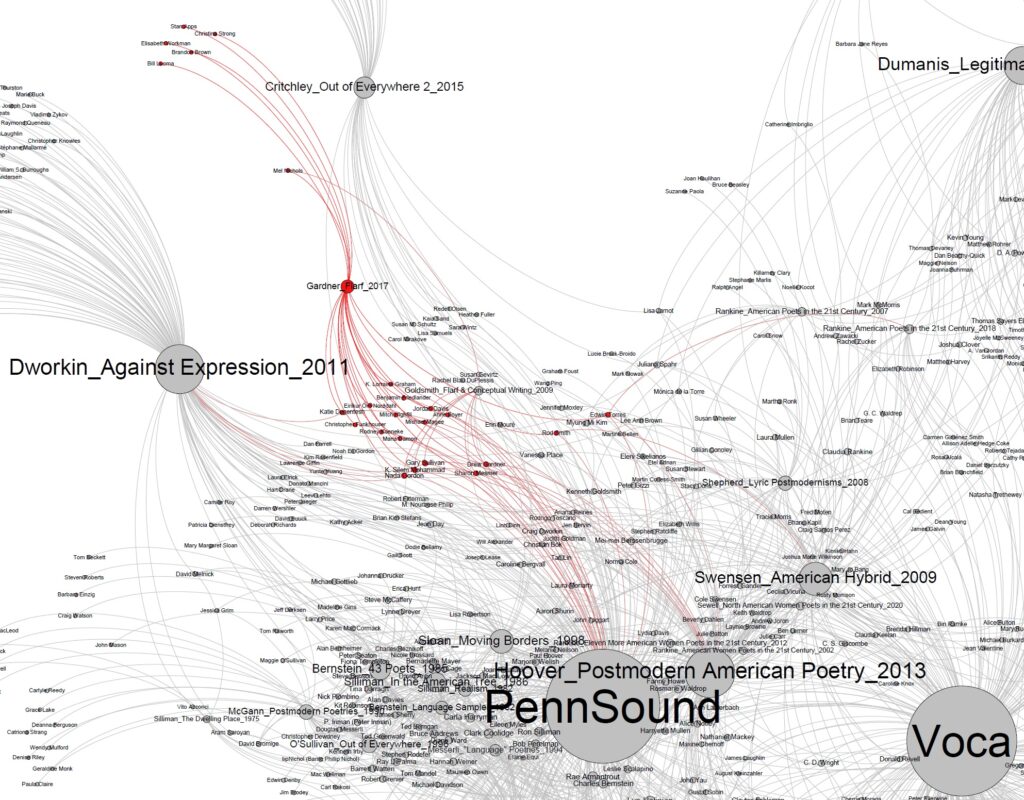

In our diagram, the cluster of Language Writing anthologies remains an isolated formation, disconnected from other poetic communities. While these anthologies maintain closure for the movement, Language Writing becomes a part of the postmodern network primarily because other anthologies in the 1990s begin to broker its relation to other networks in the cluster. According to Bruno Latour, a central tenet of network theory is that an object enters into a network of relations with other objects through its attributes, and its network is sustained "through a complex ecology of tributaries, allies, accomplices, and helpers."31 According to our network diagram, canonization of Language Writing occurs in the 1990s through the allied forces of two anthologies (figure 5): Douglas Messerli's From the Other Side of the Century: A New American Poetry, 1960-1990 (1994) and Paul Hoover's Postmodern American Poetry (1994).32 Messerli had first grouped Language Writing in Language Poetries: An Anthology (1987); however, his A New American Poetry provides structural durability to the hitherto isolated anthologies of Language Writing by brokering its relation with Allen's anthology and recent developments in American poetry, such as the second-generation New York School anthologized in Ron Padgett and David Shapiro's An Anthology of New York Poets (1970).33 The anthologies of Language Writing form a tight cluster which, in the absence of Messerli's and Hoover's anthologies, would freely float away from our diagram. In other words, teaching anthologies like Messerli's and Hoover's not only represent a selective group of influential poets, but also canonize emergent poets by brokering their networks into previously sedimented movements. As John Law states about networks, "in the end it is the configuration of the web that produces durability. Stability does not inhere in materials themselves."34

These anthologies consolidate textual networks and scenes by capturing and standardizing a diffuse and heterogeneous set of literary and social exchange. Language Writing emerged as a complex network of publication, reading, and critical spaces during its formative period in the 1970s.35 The configuration of poets in the Language Writing anthologies was part of an organizing practice that was meant to counter the decentralized practices of the establishment. As early as 1983, Bernstein had criticized the organizing practices of the "official verse culture," an establishment network of professionalization, marketing, and media: "What makes official verse culture official is that it denies the ideological nature of its practice while maintaining hegemony in terms of major media exposure and academic legitimation and funding."36 Thus, when Hoover consolidated Language Writing as part of the dominant formation in Postmodern American Poetry, his textbook definition of the period features precisely the counter-organizational practices of the postwar avant-garde: "This anthology does not view postmodernism as a single style with its departure in Pound's Cantos and its arrival in language poetry; postmodernism is, rather, an ongoing process of resistance to mainstream ideology."37 The implication is that the poets in the collection are the instigators of this "ongoing process" in the postwar period.

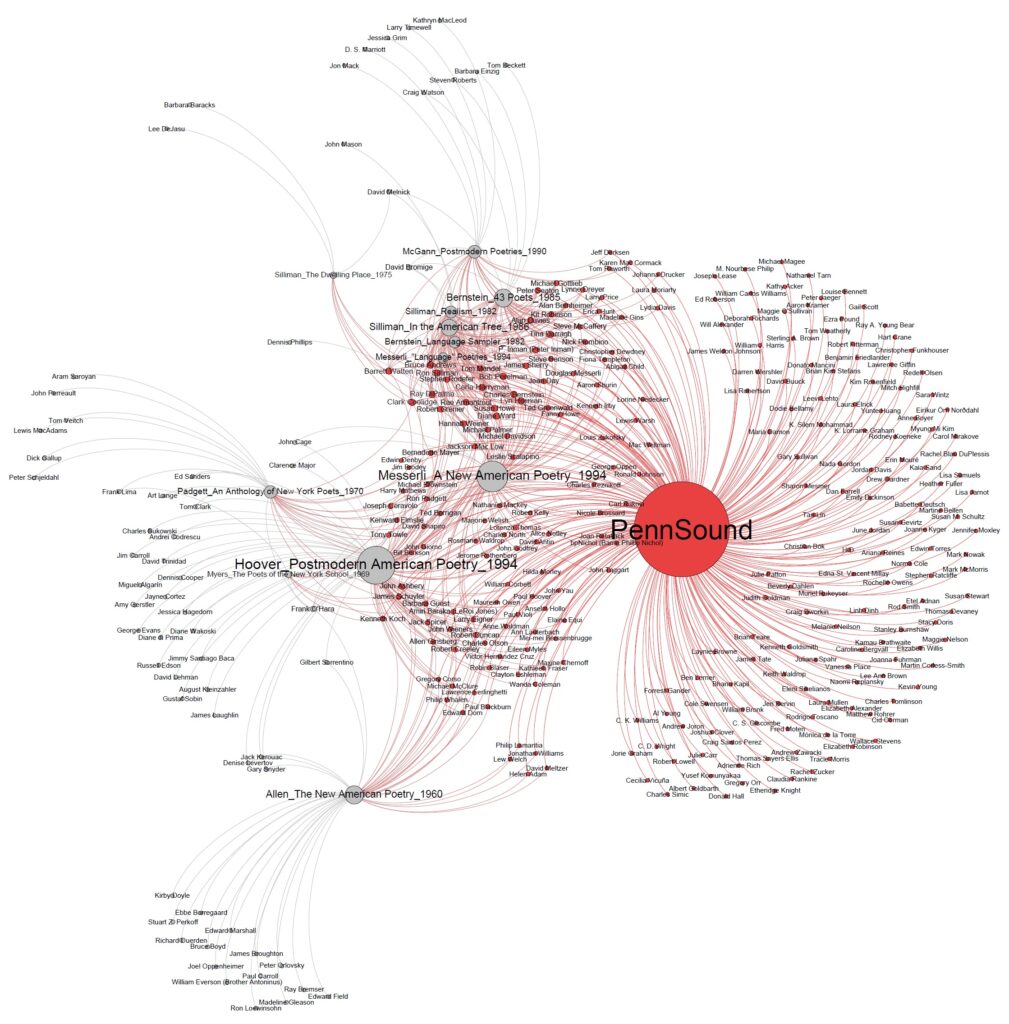

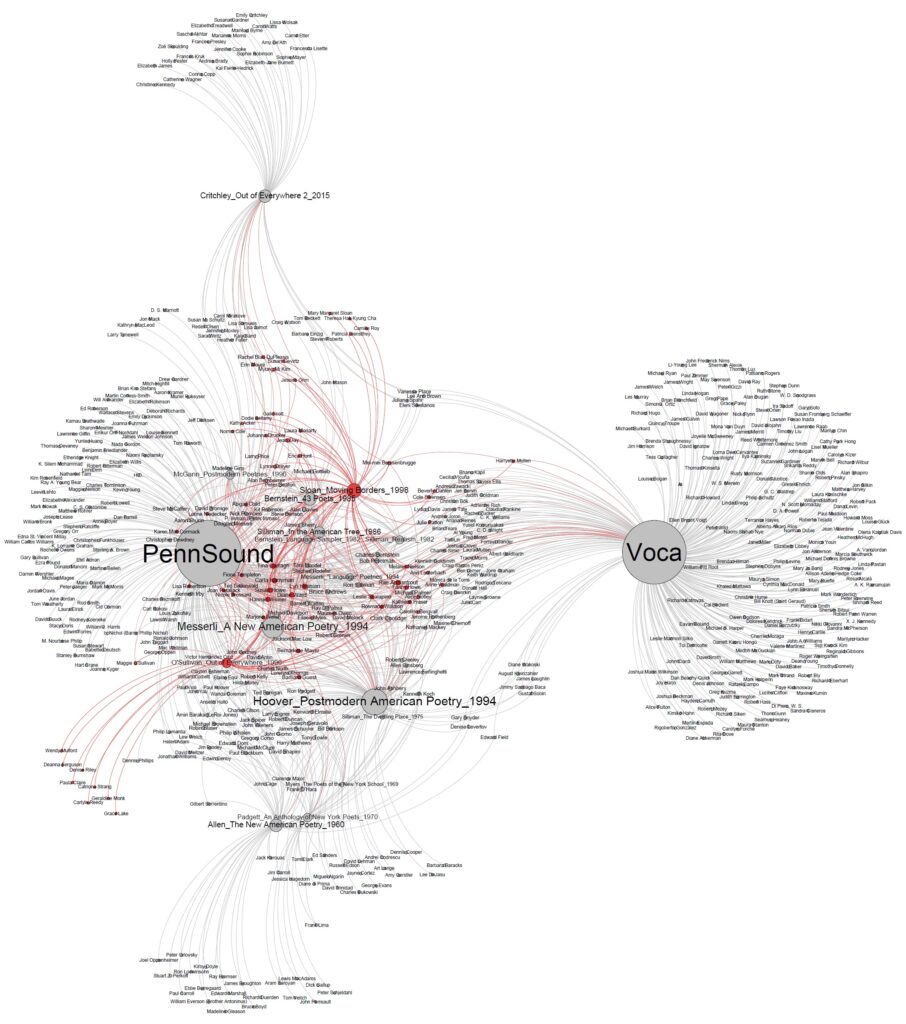

At the level of organization, PennSound's emergence in the twenty-first century should be contextualized as the consolidation of scenes of postmodern poetries into its network. We see this in PennSound's extensive representation of the period, relative to Hoover's and Messerli's collections (figure 6). Unlike the periodizing anthologies of Messerli and Hoover, which simply create ties among previously disconnected networks, PennSound encloses Language Writing within a larger body of postmodern poetry in its archival space. Following Hoover, we might even refer to PennSound as an audio archive of postmodern American poetry. According to our network diagram, PennSound's collection of heterogeneous scenes appears as a strategic structural intervention in the network formation of postwar avant-garde poetries. The imperative to combine networks and scenes of avant-garde poetry into a closed network of the postmodern period, especially through PennSound, could be construed as a response to the rising importance of mainstream poetry readings. In the earlier stages of the Program Era, as creative writing programs were being established nationwide, universities saw a proliferation of poetry readings. Analyzing his data from university-sponsored poetry readings from 1985-1987, Hank Lazer concludes that "the poetry reading, as practiced on the vast majority of university campuses, has become an increasingly narrow public event that offers economic support, as well as the prestige, publicity, and legitimation of university-sponsored readings, to that narrowly selected group of poets most willing to affirm the implied aesthetics of the current poetry reading format."38

Indeed, as opposed to PennSound, the other two audio archives in our network diagram barely contribute to the postmodern network (figure 7).

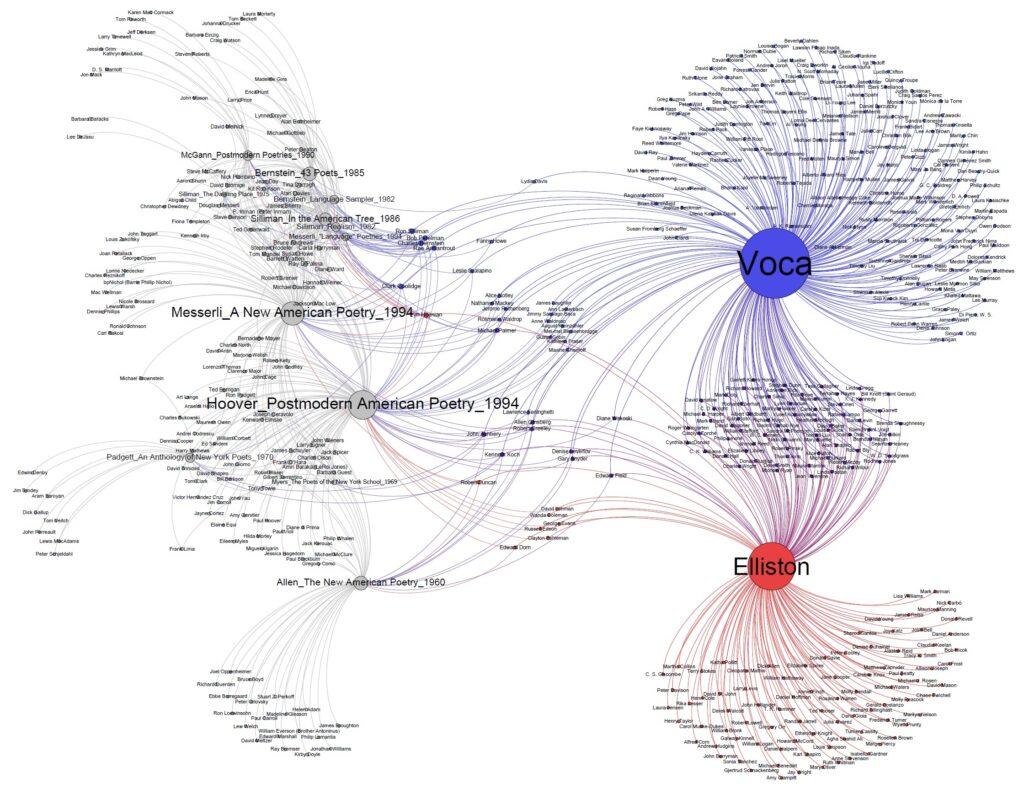

Instead, A large body of poets in Elliston and Voca come from the opposite side of our network diagram. This section comprises three mid-century anthologies we saw earlier in opposition to New American poetry, four neo-/New Formalist anthologies,39 two anthologies that are partially comprised of young graduates of creative writing programs,40 and two surveys of contemporary poetry, Helen Vendler's The Harvard Book of Contemporary American Poetry (1985) and J. D. McClatchy's The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Poetry (1990), both of which act as broker figures in bridging the different clusters of the period (figure 8).41 In our collaborative network of anthologies and audio archives, we begin to see how opposing alliances of poetic movements were formed in the postwar period. In the postmodern cluster, textual communities represented in anthologies were combined products of networks and scenes. In the "mainstream" formation, however, poetry readings at university-sponsored venues play a central role in representing textual communities that often have loose formations of network and scenes. Elliston's and Voca's closeness to these disparate groups show the influence of university-sponsored reading sites in representing groups that haven't been adequately studied as coherent poetic formations.

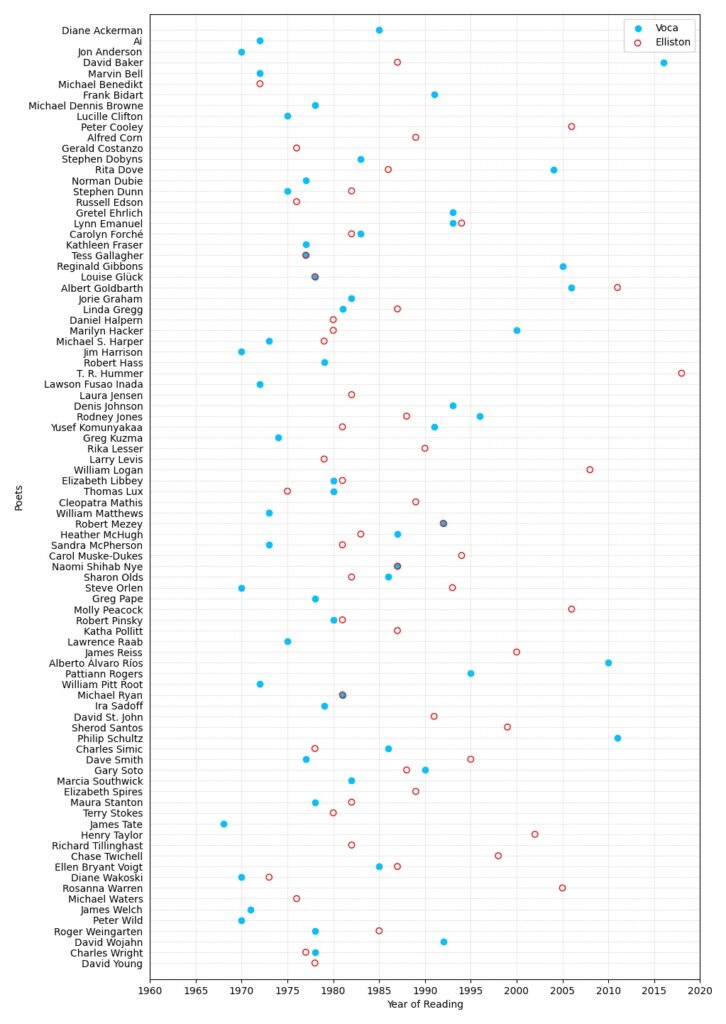

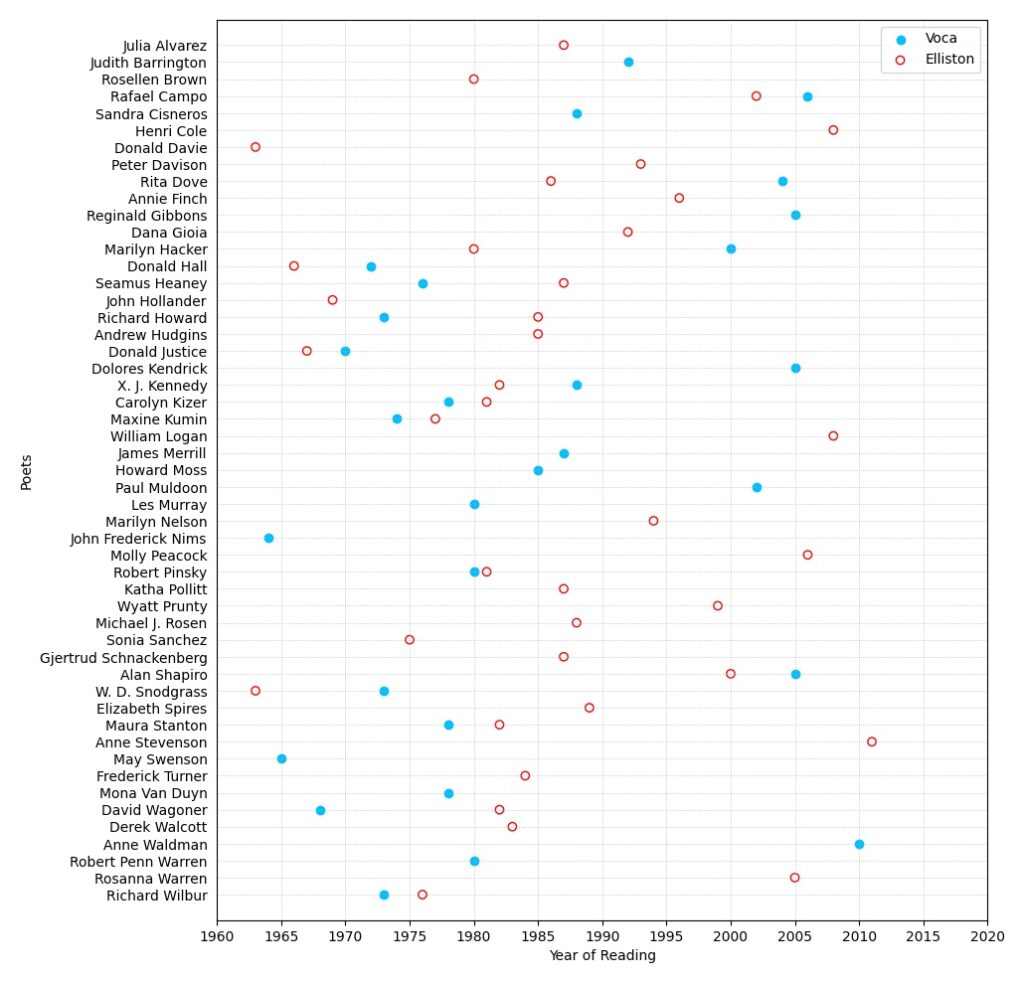

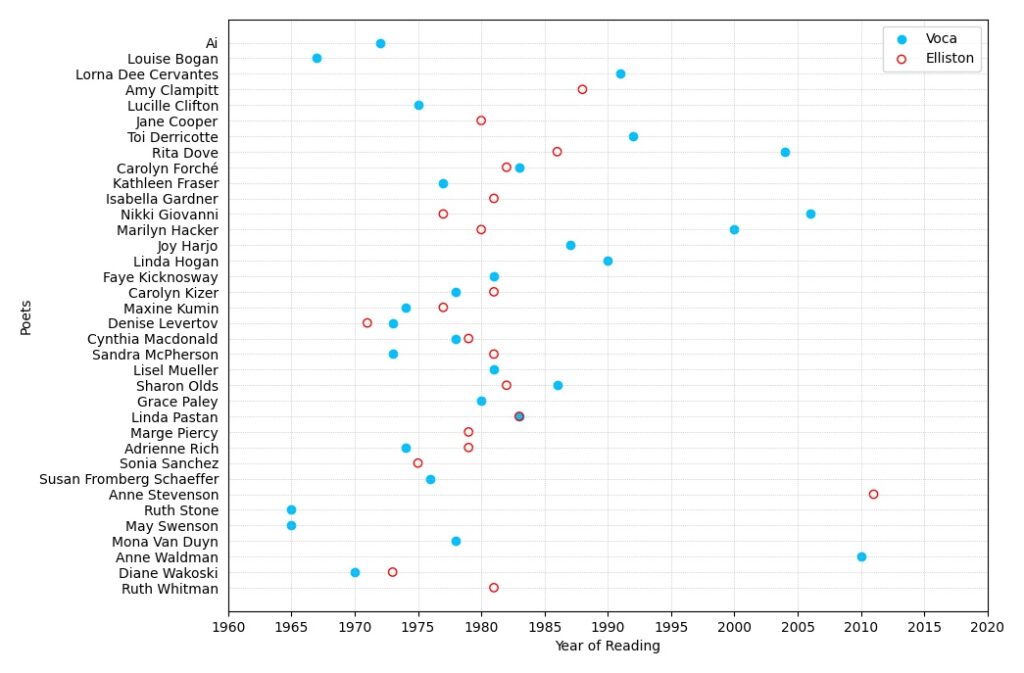

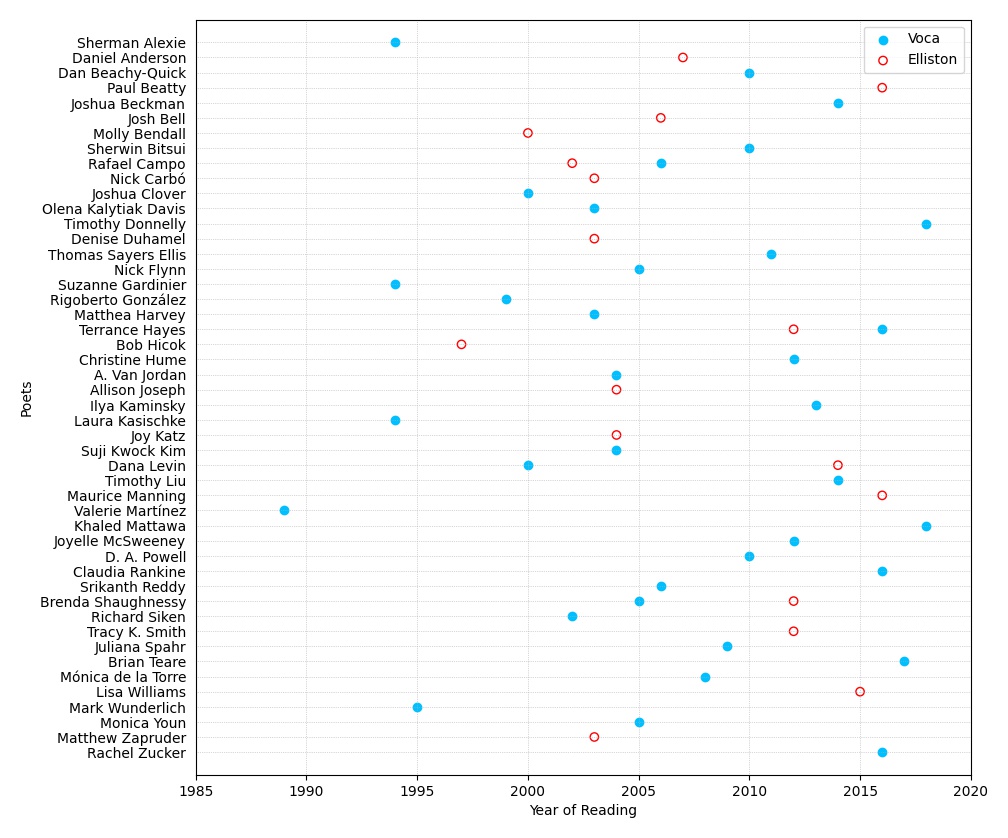

Elliston and Voca, both of whose host universities established graduate degrees in creative writing in the 1970s, are receptive to poets who are part of decentralized professional networks of mainstream poetry but are not necessarily tied to specific geographical scenes. A large body of poets in Elliston and Voca are represented in Daniel Halpern's The New Poetry Anthology (1975) and Dave Smith and David Bottoms's The Morrow Anthology of Younger American Poets (1985). According to Halpern, the poets in his anthology represent the growth of graduate programs in creative writing: "There has never been such wide-ranging interest in poetry — creative writing workshops have sprung up overnight around the country; thousands of new magazines are now in existence, with as many poets supplying their material."42 Likewise, Smith and Bottoms's poets were part of a large body of poet-professors with "one or more graduate degrees in literature or writing and [taught] both in a college."43 Poets in these two anthologies do not represent a fixed school or movement, and as Halpern asserts, "unlike the period from 1950 to 1965, when one could recognize with little trouble the groups mentioned above, the past ten years has produced a poetry that takes nourishment from a variety of camps."44 These poets came to Elliston and Voca mostly during 1970 to 2000, and as many as half of them came to Elliston in the 1980s and to Voca in the 1970s (figure 9).

Because of this alliance with loosely formed poetic communities, Elliston and Voca have not only remained sensitive to subtle changes in postwar poetry culture, but also acted as the social "scenes" for various textual communities. A case in point is the affinity of Elliston and Voca with New Formalism, which appears in the margins of our network as a poetic movement but did not succeed in providing stability to its network formation (figure 10).

New Formalist anthologies published between mid-1980s and mid-1990s began to promote revived interest in formal and metered verse as a defense against charges of elitism and conservatism.45 Each of these anthologies tried to carve a space for postwar formalism by responding to these charges.46 Since these anthologies were published during a small timespan, they appear in our network diagram as a loosely organized defense of the renewed late-twentieth century interest in formalism. We should note, however, that these anthologies, combined with the Elliston and Voca archives, represent a significant body of mainstream poets of the postwar period. And they are especially important in light of the fact that they are barely connected to the Program Era anthologies of the twenty-first century.

The Network Position of the Black Arts and Feminist Poetic Movements

Unlike the cohesive networks of poetic groups formed in aesthetic-based anthologies, the networks of identity-based revisionist anthologies, which are located at the bottom of our network diagram, remain in isolated clusters. If we recall Silliman's model that "networks typically involve scene subgroupings, while many scenes (although not all) build toward network formations," the structural relation of anthologies constituting identity-based movements to the network graph clarifies the issues regarding the representation of these poets, or lack thereof, in the audio archives. One of the anthologies based on a "scene subgrouping" that barely contributes to any network is Gwendolyn Brooks's Jump Bad: A New Chicago Anthology (1971). Based on Brooks' workshop in Chicago, Jump Bad veers away from our diagram, tethered with the help of only two nodes — Carolyn Rodgers and Haki R. Madhubuti (figure 11). Additionally, the sample of anthologies published during the Black Arts Movement form a dense cluster like the Language Writing anthologies; however, in the absence of allies like Hoover's and Messerli's periodizing anthologies, the Black Arts Movement remains a separate network in our diagram.47

A closer look at the anthologizing practices of the Black Arts Movement shows that the network indeed aspires towards the field of postwar poetry; however, the purpose of network-building seems to be to consolidate a group of representative poets who will act as mediators of the movement. In other words, the structural properties of networks in identity-based movements are crucial in disseminating representative voices. As Howard Rambsy II argues, during the Black Arts Movement "the use of a common discourse, as well as the inclusion of an interconnected group of writers, highlighted the links among the numerous anthologies published during the time period."48 The network of anthologies achieved closure through its overlapping representation of poets, and we see the evolution of this clustered network as it move towards our main network, where the latest anthologies of the period, Abraham Chapman's New Black Voices: An Anthology of Contemporary Afro-American Literature (1972) and Woodie King, Jr.'s The Forerunners: Black Poets in America (1975) are closer to the main network than other anthologies from the movement. A closed network such as this, with its interconnected nodes of poets, solidifies the recognition of the movement through its spokesperson. As Rambsy II argues, "anthologies showcased and consolidated the major trends and figures in African American poetry of the era by repeatedly publishing a common group of poems and poets."49 In the absence of alliances, however, there is a structural hole between the Black Arts Movement and other poetic communities in our diagram, which shows a gap between the movement and the larger field of postwar American poetry. That the representative poets from the Black Arts Movement occupy this structural hole, or the gap between movement's network and the period's network, demonstrates that circulating these representative poets is significant for brokering the movement's relation to the field of postwar American poetry.

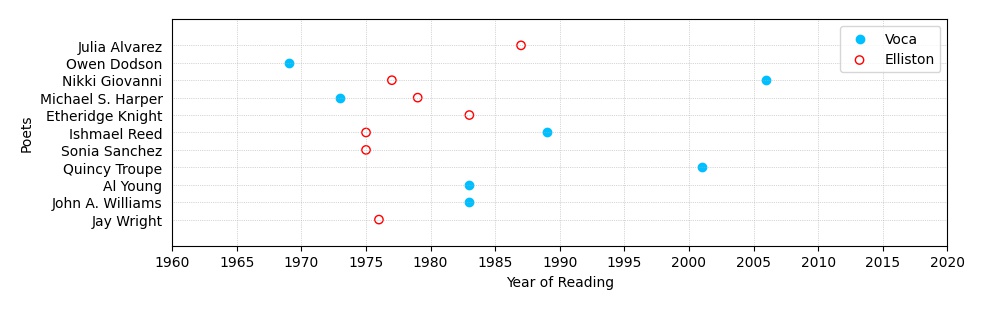

Earlier, we saw that the function of broker anthologies was to form a cohesive network of poetic clusters, such as in the postmodern network. On the other hand, these clusters of identity-based anthologies attach to the network of postwar poetry through the structural relations brokered by poets. For example, some of the women poets from the movement will be collected later in anthologies from the women's movement — Gwendolyn Brooks, Jayne Cortez, Mari Evans, Carol Freeman, Nikki Giovanni, Audre Lorde, June Jordan, Sonia Sanchez, Margaret Walker. These poets are important because they are located between two or more poetic clusters, and without them the network of the Black Arts Movement would be disconnected from the rest of the network. In other words, these are the representatives of the movement. The poets from the movement who would come to Elliston and Voca in the 1970s and 1980s feature precisely this representative group (figure 12).

One of our findings is the difference between aesthetic and social representation of poets in audio archives and teaching/textbook anthologies. The audio archives as well as the textbook anthologies occupy a central location between diverse postwar poetic movements; however, that they lean more towards identity-based movements than the audio archives also clarifies the predilection of audio archives towards aesthetic-based movements. This is especially true for the poets of the Black Arts Movement who are underrepresented in the audio archives but are represented in relatively higher proportion in teaching anthologies such as Cary Nelson's Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry (2015).50 What does this suggest? While the distribution of poetic communities in the teaching canon varies as anthologies undergo revision, audio archives generally register changes in the historical development of poetic communities. When a poetic community is represented in audio archives, it is usually because a select group of poets from its network reach the social spaces such as poetry reading venues at a university setting. Thus, the structure of a networked community becomes an important factor in the social representation of poets in identity-based movements.

Audio archives such as Voca and Elliston are records of historically consistent poetic practices, and as such they reflect the development of poetic movements. In contrast to the underrepresentation of the Black Arts Movement in the audio archives, the relatively higher representation of poets from the feminist anthologies published in the 1970s and 1980s demonstrates the significance of networks and scenes in publicizing poetic communities during the formative stage of the movement (figure 13). 1973 alone saw the publication of three anthologies which gathered the representatives of the movement.51 As Marsha Bryant explains, "reflecting major divisions within the WP Network, these anthologies' overlapping agendas proved crucial to establishing women's poetry as a curriculum and scholarly field in the United States. (Bryant's italics)"52 Bryant continues that "in 1973 American women poets were moving from the literary margins to the matrices of literary networks — becoming organizers of the literary scene instead of its perennial outsiders."53 The overlapping representation in anthologies and audio archives demonstrates the centrality of networks and scenes in canonization of poetry from the women's movement. According to Kim Whitehead, "the constant round of feminist poetry readings — both organized and open — in the 1970s illustrates the very strong commitment of feminist poets to collective reception and recognition of their poetic message."54The commitment to publicizing the collective concerns of the movement can be seen in the fairly substantial representation of women poets at Elliston and Voca, who gave readings mostly during the 1970s and 1980s (figure 14). Out of 20 poets from these anthologies represented in the Elliston archive, 19 appeared in these two decades. Likewise, 19 out of 29 poets came to Voca at the same time period as well. The influence of network-building through different forms of collectivities, such as anthologies and poetry readings, cannot be underestimated, especially in light of the fact that no single woman poet was invited to the Elliston poetry reading series during its first two decades of public readings in the 1950s and 1960s.

Before we look at the ways the Program Era in the twenty-first century merges with the delimited field of the postwar period, we should look at the additional periodizing tendencies in the 1990s with transformed organizing practices. Take, for example, Annie Finch's A Formal Feeling Comes: Poems in Form by Contemporary Women (1994), which acts as a bridge between the women's movement and New Formalism (figure 15). Published after the three neo-/New Formalist anthologies we saw earlier, Finch's anthology echoes the defense of New Formalism: "the poems collected here contradict the popular assumption that formal poetics correspond to reactionary politics and elitist aesthetics."55 Finch even stakes out a politically progressive claim in the anthology's intersection of formalism and feminism: "At their best, these poets combine the intellectual strength, emotional freedom, and self-knowledge women have gained during the twentieth century with the poetic discipline and technique that have long been the female poet's province."56 These collections are important because they provide different permutations and combinations as they compete with other periodizing practices, such as Hoover's and Messerli's anthologies we saw earlier.

In contrast to Finch's anthology, which is part of the mainstream poetry network, another group of anthologies of women's poetry have carved out different spaces as they form alliance with the postmodern cluster.57 These two anthologies, Maggie O'Sullivan's Out of Everywhere: Linguistically Innovative Poetry by Women in North America & the UK (1996) and Mary Margaret Sloan's Moving Borders: Three Decades of Innovative Writing by Women (1998), differentiate themselves from the women's movement as well as from mainstream poetry, and they have very few connections with anthologies of the women's movement of 1970s and 1980s in our network diagram (figure 16).58 Many poets in these anthologies were either previously collected in anthologies of Language Writing or they are from postmodern anthologies such as Hoover's and Messerli's, but they have few connections with the earlier anthologies such as New American poetry or the New York School. Though these anthologies appear in our network as tributaries or allies of postmodern poetry, these anthologies, in fact, corroborate the multiple networks of feminist avant-garde in the postwar period. According to Ann Vickery,

in considering questions of structure and representation, Sloan decided not to mark out regional divisions, thus generating a more fluid concept of poetic community. Moving away from anthologies that herald a "next generation," Moving Borders followed Messerli's From the Other Side of the Century: A New American Poetry, 1960-1990 in its cross-generational scope. Starting with Lorine Niedecker and finishing with Melanie Nielsen, Moving Borders reveals particular issues to be of continuing concern but approaches them through historically specific engagements. In covering only three decades, Sloan is able to emphasize a rhizomatic association between the contributors, rather than a clearly definable or linear tradition.59

We should add that Sloan's anthology is not structurally similar to that of Messerli's because it does not broker the relation between different postwar movements. On the other hand, it gathers the previously marginalized networks of feminist avant-garde as it retrospectively organizes the hitherto unacknowledged writing and publishing communities.60 As Sophie Seita argues, "magazines and forums also allowed them to forge a feminist avant-garde identity that drew on theory and formal experimentation, as well as gender and self-expression, bringing theory and identity politics into a productive relation."61 What Sloan and O'Sullivan have tried to do is highlight the networks and scenes that undergird the organization of these avant-garde and innovative women poets in the postwar period.

Hybrid Networks in the Program Era

We began our classification of anthologies by analyzing their content: revisionist anthologies of various movements, anthologies of young graduates of creative writing programs, and textbook/survey anthologies. Now we can properly make a classification based on their structure. Basically, there are two types of anthologies. First is the group of anthologies that give structure to the movement and are often organized around some combination of networks and scenes. These clusters of anthologies are located at the peripheries of our network diagram. Second is the group of anthologies that broker structural relations between various poetic communities, and they occupy a location between two or more poetic groups. In other words, these are the anthologies with high degrees of betweenness (figure 17). Betweenness centrality measures a node's overall centrality to the network structure by counting the number of shortest paths between each node in the network with every other node in the network. If many "shortest path lengths" pass through a node, it is central to the network structure. Betweenness centrality measurements are visually represented as the radius of each node in our networks, with more central nodes possessing a larger overall size, and more peripheral nodes in the network exhibiting smaller radii. Why are these broker anthologies significant for canonizing practices in postwar poetry? The poetic canon of a historical period is shaped by the combined efforts of both types of anthologies. In the earlier stages of poetic movements, anthologies form closed clusters where poets are recognized as part of a specific group. However, poets are reorganized in other poetic cannons when the broker figures re-structure their original networks. As the poets are assembled in various permutations and combinations, the canon of a historical period appears as a series of shifting relations between various poetic groups.

The canons of a historical period are formed through the strategic editorial interventions of anthologies that consolidate specific poetic formations at the exclusion of others; however, they make the networks permeable in the very process. The operative logic of network analysis is that "strategy can be understood more broadly to include teleologically ordered patterns of relations indifferent to human intentions."62 We often make judgements about the contents of anthologies based on who is included and who is excluded. However, what we have tried to show is that anthologies also restructure relations as they collect newer poets. That's essentially the business of anthologies — to collect familiar faces with unfamiliar ones, leaving out the ones that have become unfashionable. Thus, in terms of their structures, they represent different sedimentary stages of a historical period. For example, a recent textbook anthology of the period, Nelson's Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry, has a high degree of betweenness centrality because it is connected to most of the poetic groups. In terms of its structure, it represents precisely this updated set of relations configured by the broker figures in the period.

Until now, we have limited the discussion of the audio archives to their contribution in the development of networks, either synchronically for specific poetic movements or diachronically for their periodizing tendencies. We can finally begin to understand the structural properties of audio archives in relation to the historical field of postwar American poetry. It is true that these audio archives are strategically aligned to specific portions in our network diagram. Elliston and Voca are mainly oriented toward the cluster of mainstream poetry and New Formalism, and they act as social brokers for these poetic communities. PennSound represents a large group of postmodern poets who remain at the margins of the network at their respective avant-garde clusters. Additionally, these audio archives tend to collect poets who occupy the structural holes, or the gaps between two or more poetic movements. These poets are more likely to be collected in multiple anthologies, especially the ones that broker the relation between different poetic communities across the period. And the shifting relation between these poetic communities occurs precisely because these poets are the familiar faces in the canons of postwar American poetry, most of whom are more likely to be in one or more of the archives. To put a fine point on this, while Voca partially collects avant-garde poets, these poets tend to be represented more in periodizing anthologizes like Hoover's than in movement-specific anthologies. Thus, these social scenes tend to be more receptive to different poetic communities, and the networks of audio archives are quite permeable in these diagrams. Their position in the middle of aesthetic formation suggests that it is partially because of these audio archives that the canon of the postwar period is defined. To be precise, if we construe the canon of a historical field such as postwar American poetry as structural relations across cohesive networks of poetic movements, this canon is negotiated through the collaborative networks of anthologies and audio archives.

Where does this leave our understanding of the Program Era, which has reached a different phase in the last thirty years? We saw previous iterations of the Program Era in Halpern's anthology of 1975, which tried to capture the proliferation of creative writing workshops, and Smith and Bottoms's anthology of 1985, which collected creative writing graduates who teach at college. The most recent development in the Program Era is the increasing mix between profession and practice. As Juliana Spahr and Stephanie Young argue, "prior to the 1990s, many writers taught in higher education and this shaped the aesthetics of American literature, as the scholar Mark McGurl has shown in The Program Era. But it is not until the 1990s that the idea that one should necessarily turn to higher education if one wants to become a writer becomes an idea that more than 6,000 people have each year."63The three anthologies of young poets published in the twenty-first century represent this latest development (figure 18).64

They all collect poets born after 1960 who would have found a professional degree an essential part of their practice. And many of these poets will find their social scenes at Elliston and Voca in the twenty-first century (figure 19). In terms of their organization, these anthologies have not changed much. If we recall Halpern's statement that the poets in his anthology found "nourishment from a variety of camps," we can find this principle of aesthetic heterogeneity in these anthologies in that these poets are not part of any school.65 Since these anthologies were published in the earlier phase, they are barely connected to any poetic communities in our diagram. But the postwar networks can explain how these emergent formations of the Program Era become part of the period.

Of interest to us are the varieties of structures noticeable in these anthologies, especially of those that bridge the Program Era to the historical field of postwar poetry. For example, the two anthologies edited by Reginald Shepherd bridge the gap between the postwar period and the Program Era, but they do so as a team (figure 20). Shepherd's The Iowa Anthology of New American Poetries (2004) is closer to the cluster of young poets anthology, and it stakes out a compatibility between lyric and innovation by collecting "poets whose work crosses, ignores, or transcends the variously demarcated lines between traditional lyric and avant-garde practice."66 In his sequel anthology, Lyric Postmodernisms (2008), which is closer to the postmodern network and mostly connected either with the periodizing anthologies such as Messerli's and Hoover's or the revisionist anthologies of innovative poetry by women, Shepherd stakes out an even broader historical claim for his poets, thus bridging the gap between postmodernism and the Program Era: "My hope is thereby to reveal a new constellation of contemporary American poetry, one formed by the continuation, expansion, and self-questioning of the Modernist project into the postmodern era, which sometimes seems hostile to the lyric and its ever-renewed and ever-renewing possibilities."67

Anthologies like Shepherd's gradually attach to the dominant canon of the period as they re-organize groups of poets with compatible aesthetics. Another group is a series of textbook anthologies published by Wesleyan University Press (figure 21).68 Especially important in this series are the three anthologies of women poets that structurally infiltrate the postmodern network: American Women Poets in the 21st Century: Where Lyric Meets Language (2002), Eleven More American Women Poets in the 21st Century: Poetics across North America (2012), and North American Women Poets in the 21st Century: Beyond Lyric and Language (2020). According to the editors, these three anthologies were inspired by the debate ensuing from the 1999 conference, titled "Where Lyric Tradition Meets Language Poetry: Innovation in Contemporary Poetry by Women." These anthologies reclaim a group of innovative women poets writing in the lyric tradition, and many of these poets were previously published in anthologies of the poetic movements as well as those of the period.69

Because these twenty-first century anthologies reconfigure the postwar period, it is important to diagram the networked canon at a diachronic scale if we are to understand how the emergent formations gradually coalesce into the period. Consider, for instance, Cole Swensen and David St. John's anthology of the Program Era, American Hybrid: A Norton Anthology of New Poetry (2009). Swenson posits that "the contemporary moment is dominated by rich writings that cannot be categorized and that hybridize core attributes of previous 'camps' in diverse and unprecedented ways."70 The anthology, indeed, collects poets from the mainstream poetry anthologies of 1970s, 1980s, and 2000s, and it connects them with postwar poets who are more likely to be present in multiple networks such as those we saw in the periodizing anthologies of the 1990s (figure 22).

Figure 22: Cole Swensen and David St. John's American Hybrid: A Norton Anthology of New Poetry (2009).

Swensen has described the organizing principle of the anthology as aesthetic hybridity:

The rhizome is an appropriate model, not only for new Internet publications but for the current world of contemporary poetry as a whole. The two-camp model, with its parallel hierarchies, is increasingly giving way to a more laterally ordered network composed of nodes that branch outward toward smaller nodes, which themselves branch outward in an intricate and ever-changing structure of exchange and influence. Some nodes may be extremely experimental, and some extremely conservative, but many of them are true intersections of these extremes, so that the previous adjectives — well-made, decorous, traditional, formal, and refined, as well as spontaneous, immediate, bardic, irrational, translogical, open-ended, and ambiguous — all still apply, but in new combinations.71

When we plot the American Hybrid in our network diagram, we are left wondering if the model of the rhizome refers to the hybrid structure of organization or to the hybrid aesthetics of the poems. We saw earlier how the broker anthologies sought to reorganize the canon either by accumulating poets from different networks or by acting as bridges between networks. Thus, our analysis at a diachronic scale poses this question about Swensen and St. John's collection: Does the notion of hybridity refer to the anthology at the level of structure or does it refer to the anthology at the level of content?

What becomes clear to us, nevertheless, is that canons of the postwar period appear more volatile and permeable, not only in these recent twenty-first century anthologies, but also in audio archives like PennSound and Voca, especially due to the different organizations of the period in the 1990s. Thus, we wonder if the networks of literary magazines and scenes of reading have become obsolete as the organizing principles of poetic formations in the Program Era. For instance, both PennSound and Voca are hospitable to poets from the above-mentioned twenty-first century broker anthologies, where the boundary between the avant-garde and the mainstream canon is blurred (figure 23).

Figure 23: Collaborative network of twenty-first century anthologies and the audio archives.

Our intuition at the beginning of the essay was that Voca is allied with avant-garde formations as well as mainstream formation. The collaborative networks of audio archives and anthologies give us a nuanced picture. In the twenty-first century, poets are more likely to appear in multiple collections. Together, they seem to close the gap between avant-garde/innovative networks and mainstream networks. Hence, the large number of overlapping representations in PennSound and Voca. In other words, these poets bypass the need to organize first in networks of magazines or scenes of readings. An exception to this type of network formation is the Flarf group (figure 24). It emerged as a group through an email listserv in 2001, appeared in a mini-anthology alongside the Conceptual poetry group in Poetry magazine (2009), and is now consolidated in an anthology, titled Flarf: An Anthology of Flarf (2017).72 Most of the members of this group are located, of course, in PennSound only.

Conclusion

We have used the methods of social network analysis and visualization to compare the seemingly unorganized audio archives with networks of postwar poetry anthologies. We collected our data using a sample of anthologies and available digital audio archives, and we have demonstrated a method for comparing and contrasting poetic representation in different audio archives by mapping their modes of organization onto that of the anthologies. Our work gestures towards what Edward Whitley calls a "networked literary history": "A networked literary history is also an archive-rich literary history insofar as an interconnected web of texts and authors demands a full accounting of the documents and historical agents who might otherwise appear peripheral to the lineal progression of time."73 A comprehensive network will take into account multiple objects of study that form the collaborative networks of affiliation, such as correspondences, magazines, presses, not to mention, the reception of American poetry itself.

Social network analysis and visualization is an attractive method precisely because of this flexibility in data collection, analysis, and visualization. We were also excited to find that the American Poetry Archives at San Francisco State University, which boasts of 5,000 hours of recordings, is in the process of digitization. As more audio archives of poetry readings are digitized, we will have a better idea about the types of exchange and influence that occur in these social spaces and about their collective contribution to the networks of postwar American poetry. Thanks to the suggestion of our anonymous reader, we have added an important audio archive of twentieth-century avant-garde to our network: UbuWeb.74 Indeed, the audio archive UbuWeb appears as kin to the other avant-garde collection in our network — PennSound (figure 25).

Figure 25: 327 poets from UbuWeb are highlighted.

Unlike the three audio archives in our network, UbuWeb's audio archive is a collection of the international avant-garde. To be sure, international poets and artists are present in Elliston, PennSound, and Voca, and some may contain more global representation than others. However, according to the network diagram of the postwar period, these are largely archives of American poetry. UbuWeb's audio archive is, on the contrary, only partially connected to the American postmodern network (figure 26). Many of its poets and artists can be found in international groups, such as those collected in the anthologies of the Fluxus movement: La Monte Young's An Anthology of Chance Operations (1963) and Emmet Williams's An Anthology of Concrete Poetry (1967).75 Kenneth Goldsmith, founder of UbuWeb, explains that his approach to the UbuWeb archive is that of "anthologizing of anthologies": "We figured if someone went through all the trouble of sorting out obscure and esoteric types of culture and building an anthology, then it was probably worth absorbing that anthology into UbuWeb's collection."76 As Goldsmith recounts, the sound section of UbuWeb began with the digitization and/or sharing of audio anthologies such as the Futura Poesia Sonora LP and other similar compilations such as a cassette series, a CD collection or an entire blog of digitized albums.77 As UbuWeb brokers the network between these audio anthologies by collecting them in a common digital space, it also bridges the gap between the international Fluxus movement and the postmodern network of American poetry.

Ankit Basnet is a doctoral candidate in English and Comparative Literature at the University of Cincinnati, where he studies modern and contemporary American poetry and performs research on the audio archives at the Digital Scholarship Center.

James Lee is the Director of the Digital Scholarship Center, and is an Associate Professor of Digital Humanities at the University of Cincinnati. His research and teaching focus on the areas of digital humanities, machine learning and text mining techniques on historical archives, social network analysis, and data visualization. Much of his work has used machine learning methods applied to large text corpora and other unstructured datasets to rethink what it means to perform historical analysis. His research also involves information retrieval and ways to visualize the results of machine learning algorithms in a human-interpretable way that enables non-technical audiences to glean useful information from the data. More recently, his research has branched out into fascinating collaborations applying digital humanities methods with partners in biomedical informatics, law, design, and archeology. His work has been supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the National Science Foundation.

References

- We thank Xuemao Wang, Jay Twomey, Leah Stewart, Jenn Glaser, Michael Hennessey and Linda Newman for their contributions to the Elliston Digital Humanities project. We are also grateful to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation's Public Knowledge program for sustaining this work. [⤒]

- Ron Silliman, "The Political Economy of Poetry," in The New Sentence (New York: Roof Books, 2001), 28-29. An earlier version of this essay appeared in the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E issue of Open Letter 5, no. 1 (Winter 1981): 52-65. [⤒]

- Ibid., 29. [⤒]

- Charles Bernstein, "Making Audio Visible: The Lessons of Visual Language for the Textualization of Sound," Text 16 (2006): 283. [⤒]

- Raphael Allison, Bodies on the Line: Performance and the Sixties Poetry Reading (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2014); Libbie Rifkin, Career Moves: Olson, Creeley, Zukofsky, Berrigan, and the American Avant-Garde (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2000), 13-26. Lytle Shaw, Narrowcast: Poetry and Audio Research (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2018). [⤒]

- Marit J. MacArthur, Georgia Zellou, and Lee M. Miller, "Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets," Journal of Cultural Analytics, April 18, 2018. [⤒]

- For an alternative study of canon as a matter of popularity and prestige, see Mark Algee-Hewitt, Sarah Allison, Marissa Gemma, Ryan Heuser, Franco Moretti, and Hannah Walser, "Canon/Archive: Large-Scale Dynamics in the Literary Field," in Canon/Archive: Studies in Quantitative Formalism From the Stanford Literary Lab, ed. Franco Moretti (New York: n+1 Books, 2017), 268 n. 20. [⤒]

- Loren Glass, "Introduction: From the Pound Era to the Program Era, and Beyond," in After the Program Era: The Past, Present, and Future of Creative Writing in the University, ed. Loren Glass (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2016), 1. [⤒]

- Danial Kane, All Poets Welcome: The Lower East Side Poetry Scene in the 1960s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003); Bill Mohr, Hold-Outs: The Lost Angeles Poetry Renaissance, 1948-1992 (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2011). [⤒]

- For the list of authors in Elliston, see "The Elliston Project," University of Cincinnati Digital Resource Commons. For PennSound, we selected poets from the compiled authors list rather than the whole archive, "Authors," PennSound. For the Voca digital collection, see "Voca," The University of Arizona Poetry Center. In collecting our data on authors, we have selected the published poets from these archives, but we do not classify the contents of the audio. Hence, both Edgar Allan Poe and Jerome McGann from PennSound's authors list are represented in our graph although the audio is a recording of McGann reading Poe's poetry. Additionally, a handful of poets in our graph do not have audio recordings at Elliston and Voca, so we have relied on their presence on the catalog's metadata. For instance, we have collected John Berryman because he was an Elliston poet-in-residence in 1952-1953, but we do not have his audio, potentially owing to various reasons — the analogs are missing, or the reading was not recorded, or he did not give a reading at all. [⤒]

- Seth Abramson, "From Modernism to Metamodernism: Quantifying and Theorizing the Stages of the Program Era," in After the Program Era: The Past, Present, and Future of Creative Writing in the University, ed. Loren Glass (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2016), 237-238. [⤒]

- "Gephi: The Open Graph Viz Platform," Gephi.org, 2017. [⤒]

- Richard Jean So and Hoyt Long, "Network Analysis and the Sociology of Modernism," Boundary 2 40, no. 2 (2013): 157-158. [⤒]

- Ibid., 148. [⤒]

- Jeremy Braddock, Collecting as Modernist Practice (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 3. [⤒]

- Ibid., 4. [⤒]

- We borrow these classifications from Alan Golding, From Outlaw to Classic: Canons in American Poetry (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1995), 28-40. [⤒]

- Ibid., 30. [⤒]

- Golding classifies these anthologies of young poets as teaching anthologies: "The mainstream survey does not present itself as a textbook in the way that The Norton Anthology of Poetry does, but it is most likely to be used in the classroom. It differs from the Norton in various ways, ways that make it resemble in format — though not in tone, purpose, or content — the revisionist collection . . . Frequently the mainstream survey draws on and addresses the MFA/Creative Writing Program circuit for its contents and audience" (35). We will see later that these anthologies lead to the formation of revisionist anthologies of the twenty-first century in ways Golding couldn't have anticipated in the 1990s. [⤒]

- Donald Allen, ed., The New American Poetry: 1945-1960 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1960); John Ciardi, ed., Mid-Century American Poets (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1950); George P. Elliott, ed., Fifteen Modern American Poets (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1956); Donald Hall, Robert Pack, and Louis Simpson, eds., New Poets of England and America (Cleveland: Meridian Books, 1957). [⤒]

- Alan Golding, "The New American Poetry Revisited, Again," Contemporary Literature 39, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 202. [⤒]

- Marjorie Perloff, "Whose New American Poetry? Anthologizing in the Nineties," Diacritics 26, no. 3/4 (Autumn-Winter 1996): 107. [⤒]

- As Edward Brunner argues, ten out of fifteen poets in Elliott's 1956 anthology were already published in Ciardi's anthology of 1950, but Elliott had a different design for his anthology: "While Ciardi still dreamed of capturing the attention of the general reader, Elliot was targeting the college student." Edward Brunner, Cold War Poetry (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2001), 57. [⤒]

- Allen, preface to The New American Poetry, xi. Consider Allen's statement as a response to Robert Frost's introduction to New Poets of England and America, where Frost assured that the anthology will find an institutional home in college classrooms: "As I often say a thousand, two thousand, colleges, town and gown together in the little town they make, give us the best audiences for poetry ever had in all this world. I am in on the ambition that this book will get to them—heart and mind." Robert Frost, introduction to New Poets of England and America, 12. [⤒]

- Allen, preface to The New American Poetry, xi. Compare Allen's statement with Ciardi, who had referred to his group as "the latest generation of American poets — those poets reaching their maturity around the mid-century" who have produced "their best work in the last 10 to 15 years." John Ciardi, foreword to Mid-Century American Poets, x, xxvii. Likewise, Elliott states that his group "represent[s] the middle generation of American poets, not those like Frost, Cummings, Stevens, W. C. Williams, Jeffers, MacLeish, and Ransom, whose reputations are by now quite firmly fixed, nor those like Hecht, Merwin, and Moss, who are still on the way." George P. Elliott, preface to Fifteen Modern American Poets, xi. [⤒]

- Lisa Marie Chinn, Brian Croxall, and Rebecca Sutton Koeser, "Networks," Networking the New American Poetry. [⤒]

- Allen states this about his mode of organization of poetic schools: Publication in same literary magazine and academic affiliation (The Black Mountain poets); local poetry readings (San Francisco Renaissance); publication in same literary magazine and local poetry readings (The Beat Generation); coterie and graduates of same school (the New York Poets); younger poets without a coherent geographical scene or print network (the fifth group). Allen, preface to The New American Poetry, xii-xiii. [⤒]

- Ron Silliman, ed., "The Dwelling Place: 9 Poets," Alcheringa 1, no. 2 (1975): 104. [⤒]

- Charles Bernstein, ed., "43 Poets (1984)," Boundary 2 14, no. 1/2 (Fall 1985/Winter 1986): 1-113; Charles Bernstein, ed., "Language Sampler," The Paris Review, no. 86 (Winter 1982); Douglas Messerli, ed., "Language" Poetries: An Anthology (New York: New Directions, 1987); Jerome McGann, ed., "Postmodern Poetries: An Anthology of Language Poets from North America and the United Kingdom," Verse 7, no. 1 (1990): 5-73; Silliman, "The Dwelling Place," 104-120; Ron Silliman, ed., In the American Tree: Language, Realism, Poetry (Orono: National Poetry Foundation, University of Maine at Orono, 1986); Ron Silliman, ed., "Realism: An Anthology of 'Language' Writing," Ironwood, no. 20 (1982): 62-142. [⤒]

- So and Long, "Network Analysis," 167. [⤒]

- Bruno Latour, "Networks, Societies, Spheres: Reflections of an Actor-Network Theorist," International Journal of Communication 5 (2011): 799. [⤒]

- Paul Hoover, ed., Postmodern American Poetry: A Norton Anthology (New York: W. W. Norton, 1994); Douglas Messerli, ed., From the Other Side of the Century: A New American Poetry 1960-1990 (Los Angeles: Sun & Moon Press, 1994); For a discussion of these anthologies at length, see Perloff, "Whose New American Poetry?" 104-123. [⤒]

- Ron Padgett and David Shapiro, eds., An Anthology of New York Poets (New York: Vintage Books, 1970). [⤒]

- John Law, "Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics," in The New Blackwell Companion to Social Theory, ed. Bryan S. Turner (Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009), 148. [⤒]

- See Charles Bernstein, "The Expanded Field of L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E," in Pitch of Poetry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 60-77; and Bob Perelman, The Marginalization of Poetry: Language Writing and Literary History (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 11-21. The network formation in Language Writing is facilitated by its material structures, and the strength of interconnections in this network endure additionally through, as Law argues, "discourses [that] define conditions of possibility, making some ways of ordering webs of relations easier and others difficult or impossible." Law, "Actor Network Theory," 149. Language Writing's insistence on merging theory with the poetics of language and its divergence from the "expressive," voice-based poetics constitute the discursive practice that set them apart from mainstream poetry. Silliman claimed this poetics a divergence from the Romantic tradition: "Unlike the Romantics, these writers do not simply sing of the self. Instead, these works investigate its construction through the medium of language." Ron Silliman, "Realism," in Realism: An Anthology of 'Language' Writing, 65. In Bernstein's expanded program, Language Writing "keep[s] open the question of how meaning is constituted and take[s] this question to have political, tonal, aesthetic, syntactic, grammatical, prosodic, sociological, physical, and biological consequences." Charles Bernstein, afterword to 43 Poets (1984), 112. Silliman, in a later anthology, characterized this rejection of "speech-based poetics" as the community's innovative stance: "Any new direction would require poets to look (in some ways for the first time) at what a poem is actually made of — not images, not voice, not characters or plot, all of which appear on paper, or in one's mouth, only through the invocation of a specific medium, language itself." Ron Silliman, "Language, Realism, Poetry," in In the American Tree, xvi. Messerli would characterize this investigation of language as Language Writing's difference from the mainstream poetics: "Language is perception, thought itself; and in that context the poems of these writers do not function as 'frames' of experience or brief narrative summaries of ideas and emotions as they do for many current poets." Douglas Messerli, introduction to "Language" Poetries: An Anthology, 2. [⤒]

- Charles Bernstein, Content's Dream: Essays, 1975-1984 (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2008), 248. [⤒]

- Paul Hoover, introduction to Postmodern American Poetry, xxvi. [⤒]

- Hank Lazer, Opposing Poetries: Issues and Institutions (Evanston: Northwestern UP, 1996), 50. For Lazer, these poetry reading venues are parts of the "official verse culture" because they not only create professional spaces for poets, but also allow social scenes where voice-based lyric poetry could prosper: "The poetry reading, with a few notable exceptions, exists in complicity with the dominance of the carefully crafted voice-lyric" (52). [⤒]

- Philip Dacey and David Jauss, eds., Strong Measures: Contemporary American Poetry in Traditional Forms (New York: Harper & Row, 1986); Annie Finch, ed., A Formal Feeling Comes: Poems in Form by Contemporary Women (Brownsville: Story Line Press, 1994); Mark Jarman and David Mason, eds., Rebel Angels: 25 Poets of the New Formalism (Brownsville: Story Line Press, 1990); Robert Richman, ed., The Direction of Poetry: An Anthology of Rhymed and Metered Verse Written in the English Language Since 1975 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1988). [⤒]

- Daniel Halpern, ed., The New Poetry Anthology (New York: Avon Books, 1975); Dave Smith and David Bottoms, eds., The Morrow Anthology of Younger American Poets (New York: Quill, 1985). [⤒]

- J. D. McClatchy, ed., The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Poetry (New York: Vintage Books, 1990); Helen Vendler, ed., The Harvard Book of Contemporary American Poetry (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985). [⤒]

- Halpern, introduction to The New Poetry Anthology, xxix. [⤒]

- Smith and Bottoms, "The Anthology in Our Heads," in The Morrow Anthology, 18. [⤒]

- Halpern, introduction, xxxii. [⤒]

- See Ariel Dawson, "The Yuppie Poet," AWP Newsletter, May 1985, 5-6; Ira Sadoff, "Neo-Formalism: A Dangerous Nostalgia," The American Poetry Review 19, no. 1 (January/February 1990): 7-13; and Diane Wakoski, "The New Conservatism in American Poetry," American Book Review 8, no. 4 (May/June 1986). [⤒]

- Dacey and Jauss, in the earliest neo-formalist collection, claimed that "free verse was once revolutionary, but it has long since become the fashion. Given this fact, it is easy to understand why the young poet Barton Sutter has said, 'The most radical poem a poet can write today is a sonnet.'" They presented hybrid approaches to poetic forms, and they included "poets [who] have been less in love with measurements — with 'structure' — than with 'form,'" in order to "highlight the finest achievements in both free and formal verse." Philip Dacey and David Jauss, introduction to Strong Measures, 1, 2, 4. Robert Richman collected instances of strong interest in formalism, and "the consistent use of a metrical foot" in the anthology's poems "invalidates the countless critical judgments, expressed in the sixties and seventies, of the death of metrical verse." Richman, introduction to The Direction of Poetry, xv-xvi. More rhetorical in tone and less programmatic in organization, Jarman and Mason claimed that "these poets represent nothing less than a revolution" and that "these twenty-five writers are among those who will lead American poetry into the 21st century." Mark Jarman and David Mason, preface to Rebel Angels, xv, xix. [⤒]

- John H. Bracey Jr., Sonia Sanchez, and James Smethurst, eds., SOS-Calling All Black People: A Black Arts Movement Reader (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014); Gwendolyn Brooks, ed., Jump Bad: A New Chicago Anthology (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1971); Abraham Chapman, ed., New Black Voices: An Anthology of Contemporary Afro-American Literature (New York: Mentor, 1972); Leroi Jones and Larry Neal, eds., Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1968); June Jordan, ed., soulscript: Afro-American Poetry (New York: Zenith Books, 1970); Woodie King, Jr., ed., The Forerunners: Black Poets in America (Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1975); Clarence Major, ed., The New Black Poetry (New York: International Publishers, 1969); Dudley Randall and Margaret G. Burroughs, eds., For Malcolm: Poems on the Life and the Death of Malcolm X (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1969). [⤒]

- Howard Rambsy II, The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2011), 50. [⤒]

- Ibid., 76. [⤒]

- The contemporary textbook anthologies in our diagram are Steven Gould Axelrod, Camille Roman, and Thomas Travisano, eds., The New Anthology of American Poetry, Volume Three, Postmodernisms 1950-Present (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2012); Cary Nelson, ed., Anthology of Contemporary American Poetry, 2nd edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015); Jahan Ramazani, Richard Ellmann, and Robert O'Clair, eds., The Norton Anthology of Modern and Contemporary Poetry, vol. 2, 3rd edition (New York: W. W. Norton, 2003). [⤒]

- Laura Chester and Sharon Barba, eds., Rising Tides: 20th Century American Women Poets (New York: Washington Square Press, 1973). Florence Howe and Ellen Bass, eds., No More Masks! An Anthology of Poems by Women (New York: Anchor Press, 1973). Lucille Iverson and Kathryn Ruby, eds., We Become New: Poems by Contemporary American Women (New York: Bantam Books, 1975). Marge Piercy, ed., Early Ripening: American Women's Poetry Now (New York: Pandora, 1987); Barbara Segnitz and Carol Rainey, eds., Psyche: The Feminine Poetic Consciousness, an Anthology of Modern American Women Poets (New York: Dial Press, 1973). [⤒]

- Marsha Bryant, "The WP Network: Anthologies and Affiliations in Contemporary American Women's Poetry," in A History of Twentieth-Century American Women's Poetry, ed. Linda A. Kinnahan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 197. See Bryant for additional history of women's poetry anthologies from the movement. [⤒]

- Ibid., 200. [⤒]

- Kim Whitehead, The Feminist Poetry Movement (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1996), 31. [⤒]

- Finch, introduction to A Formal Feeling Comes, 1. [⤒]

- Ibid., 5. [⤒]

- Maggie O'Sullivan, ed., Out of Everywhere: Linguistically Innovative Poetry by Women in North America & the UK (East Sussex: Reality Street, 1996); Mary Margaret Sloan, ed., Moving Borders: Three Decades of Innovative Writing by Women (Jersey City: Talisman House, 1998). [⤒]

- O'Sullivan writes that the poets in her anthology "through brave insistence and engagement in explorative, formally progressive language practices, find themselves excluded from conventional, explicitly generically committed or thematic anthologies of women's poetry. Excluded from 'women's canons', such work does, however, connect up with linguistically innovative work by men who have themselves also transcended the agenda-based and cliché-ridden rallying positions of mainstream poetry." Maggie O'Sullivan, introduction to Out of Everywhere, 9-10. Likewise, Sloan distinguishes her anthology from those published during the women's movement: "The writing here took an alternative path to the one chosen by other women writing in the early seventies, a writing predicated on a unified, vocalized 'I' and on the maintenance of received forms of the poem newly filled with different subject matter." Mary Margaret Sloan, introduction to Moving Borders, 6. [⤒]

- Ann Vickery, Leaving Lines of Gender: A Feminist Genealogy of Language Writing (Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, 2000), 146. [⤒]