Issue 7: Post45 x Journal of Cultural Analytics

1: Port Townsend

From Port Townsend, Washington, you can watch the Puget Sound meet the Salish Sea: the small water turns west toward the open ocean. In 1982, James Laughlin spent a week at a writers' retreat in Port Townsend. He joined a small group that included poet Tess Gallagher, her partner Raymond Carver, and Carver's notorious editor Gordon Lish. Carver had recently published his second short story collection with Lish at Knopf. The two had become a literary power couple, the sine qua non of dirty realism, triumphing amid a vogue for short fiction in a minimalist style.

As significant for literary history was Laughlin's encounter with a young publisher named Scott Walker who, for eight years, had been publishing Gallagher and other poets from his nearby letterpress operation under the colophon of Graywolf Press.

Laughlin, the aging heir to a Pittsburgh steel fortune, was a publishing legend. In 1936, at the age of twenty-two and at the advice of Ezra Pound, he founded New Directions, which quickly became the premier avant-garde publishing house, almost synonymous with literary modernism in the US. Early on, Laughlin frequently published adept attacks against Random House as the commercial foil to New Directions, such as James T. Farrell's "Will the Commercialization of Publishing Destroy Good Writing?" in New Directions 9. Laughlin's strategy was clever. Not only was he filling, with his front and backlists, a market niche prepared by Random House's publication of work like James Joyce's Ulysses and Gertrude Stein's oeuvre, but his attacks themselves were a commercial tactic. They made his brand. Laughlin was "disavowing an interest in marketing while constantly trying to think up new marketing techniques."1 This is a familiar gambit: to claim authenticity by differentiating oneself from a sell-out, then to use that authenticity for profit.

In Port Townsend, Laughlin and Walker struck up a friendship. In the ensuing years, Walker would vacation at Laughlin's ski resort in Alta, Utah, and Graywolf would publish Laughlin's lectures on Pound. Laughlin became a mentor and a model for Walker as Graywolf emerged at the forefront of a movement: nonprofit publishing.

But in 1982, that all lay ahead. Graywolf remained close to its counterculture origins. "Small was beautiful," Walker later remembered.2 Dozens if not hundreds of fly-by-night presses had sprouted and vanished since the late 1950s thanks to the widespread availability of inexpensive mimeograph machines, a predecessor to photocopiers. The Mimeo Revolution provided the print technology for the postwar era's leading poetry movements. Lawrence Ferlinghetti published Allen Ginsberg's Howl with a mimeograph in 1956. LeRoi Jones (later, Amiri Baraka) and Diane Di Prima published the New York School, the Black Mountain School, and the Beat Movement in The Floating Bear, sending mimeo newsletters to their mailing list between 1961 and 1969.3 In the late 1970s and 1980s, photocopiers phased out mimeographs: Bruce Andrews and Charles Bernstein launched L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E through offset printing and photocopies. Beginning in the mid 1980s, the personal computer made desktop publishing possible, phasing out photocopying.

Walker was one of several publishers inspired by the Mimeo Revolution and a counterculture arts-and-crafts ethos to learn how to use a letterpress to make beautiful books. (He was taught by Sam Hamill and Tree Swenson of Port Townsend's Copper Canyon Press.) That was how he started, in 1974. That's what he was doing in 1982. He later claimed that he "didn't make more than $7,000 the first 10 years" and that he "almost gave up."4

He met Laughlin at a pivotal moment. Multinational conglomerates rapidly bought out publishers in the late 1970s, leading authors to worry that the pressure to prioritize the bottom line would ruin opportunities for good books.5 In 1980, E. L. Doctorow, esteemed Random House writer and vice president of the American Center of PEN International, confronted publishing executives over the fate of the literary world before a committee of the US Senate. He and others argued that conglomerates should be broken up to save literature. They lost that argument. But desktop computing and improved infrastructure for distribution opened another way, yet nascent in 1982. What if, like dance, opera, and orchestras, literary books could be subsidized by state-sponsored grant funding and private philanthropy? Such financial support would, according to this line of reasoning, liberate publishers from the demands of the market. To access it, publishers would need to become nonprofit organizations.

Over the next twenty-five years, nonprofit publishing transformed the US literary landscape. Such publishers as Arte Público, Coffee House, Dalkey Archive, and Milkweed made space for ethnic literatures, translations, and literary experimentation. Graywolf became the most successful of all. In 2018, Graywolf had a budget of $4 million. Its writers regularly win large awards, including the National Book Award, the Pulitzer Prize, and MacArthur Grants. It is arguably the New Directions of the twenty-first century.

State money and philanthropic money come with expectations. As nonprofits published writing that the conglomerates deemed unfit for the market, they chose and shaped that writing according to their own financial needs. What priorities would funders, explicitly or not, want to see expressed in the literature they financed? What would have success in nonprofits' smaller but still consequential markets? What values, aesthetic and otherwise, were encoded in the missions of government units and foundations that could guide the editorial practices of the nonprofits? Despite the cant of liberation, markets still mattered to nonprofits: their innovation came from balancing market success with other priorities.

We discovered that these two different ways of structuring publishers' finances — conglomerate and nonprofit — created a split within literature, yielding two distinct modes of American writing after 1980. This essay characterizes the two modes, explains how the split between them happened, and illustrates the significance of this shift for the rise of multiculturalism.

2: Burn This, Will You?

At the National Book Critics Circle award ceremony in 1990, Laughlin, by then a septuagenarian, extended his lifelong refrain, denouncing big presses as "merchants of canned cod who are ruining our culture" and urging the assembled critics to devote their attention to small presses, including Coffee House and Graywolf.6 The occasion for his ire was the firing of André Schiffrin, Pantheon's managing director, by Random House's incoming CEO Alberto Vitale. Laughlin called it a "disgusting scandal."7 Doctorow, accepting the night's fiction award as a Random House author, said, "Even if no censorship was intended by its application of its own bottom-line criteria to its Pantheon division, the effect is indeed to still a voice, to close a door against part of the American family."8 Laughlin criticized what he viewed as the formulaic production of conglomerate publishers. Doctorow called on publishers to prioritize the national interest over the bottom line.

Schiffrin's firing was an event in the publishing world. Under his leadership, Pantheon had built a reputation as a leftist bastion, home to Simone de Beauvoir, Noam Chomsky, Marguerite Duras, and Michel Foucault. Vitale's predecessor, Robert L. Bernstein, had long insulated Schiffrin from conglomerate pressure, but Vitale changed course, an ominous portend. Without Bernstein's support, these writers might not have found their audience in the US.

Many on the Pantheon staff resigned. Authors, including Barbara Ehrenreich, Oliver Sacks, and Kurt Vonnegut, gathered outside Random House headquarters to protest. It was, they felt, the latest battle in the decades-long war of attrition that was conglomeration, which they were losing. But senior editors, including Joni Evans and Sonny Mehta, defended Vitale in the New York Times, asking "why Pantheon shouldn't live by the same fiscal rules as the rest of us at Random House and throughout the industry."9 The same day, Knopf editor Robin Desser (now vice president and editorial director) wrote to Scott Walker. "It's very strange here without Pantheon — for at present there really is none."10 She felt ambivalent, caught between respect for her superiors ("how can Joni and Sonny . . . be wrong?") and her sense that "this whole business is disgusting and that actually they were going to castrate André bit by bit so it is better that he went this way, righteous, with all the foolish and wonderful connotations righteous implies."11 The affair was contentious enough that she ended with the request, "Burn this, will you?"12

The demise of Pantheon galvanized literary types to look for alternatives to the conglomerates, as when Laughlin petitioned the NBCC to look to Graywolf and its brethren. But the scene was bleak, if less so for poetry, which had migrated to nonprofits, than for fiction, which the nonprofits, by and large, had yet to take up.

Predecessors to the nonprofits, presses that positioned themselves as the obverse to behemoths like Random House, struggled through the 1970s and 1980s. Inflation outpaced wages; books exceeded budgets. New Directions carried on as the publisher of modernism, bringing out new editions of old works by its mainstays, Ezra Pound, Tennessee Williams, and William Carlos Williams, along with Jorge Luis Borges, HD, and Ronald Firbank, while also becoming home to postmodernist John Hawkes. Laughlin largely rested, this is to say, on his laurels.

Grove, which burned bright in the 50s and 60s, flamed out with the first wave of conglomeration. Feminists occupied Grove's offices on April 13, 1970, to protest its sexism and demand union recognition. The avant-garde publisher used its resistance to conglomeration as justification for rejecting the union, noting "the wave of corporate mergers sweeping over the publishing industry and insist[ing] that, insofar as they 'have been virtually alone in resisting this trend,' they should also be exempted from the unionization efforts that were a response to it."13 This did not go over well. In the end, Grove had to downsize dramatically and even then, to survive, rely on Jason Epstein, the legendary Random House editor, "to prop up the company."14 The outsider had to kiss the ring. "Epstein convinced an aging Bennett Cerf that it would be tragic to let Grove go under, so for much of the 1970s Random House distributed Grove's titles, in return for which it received a portion of the profits."15 And yet, Grove managed to publish a few important new works in these decades by novelists including Kathy Acker, Jerzy Kosinski, Leslie Marmon Silko, and Jeanette Winterson.

Farrar, Straus and Giroux (FSG) held out as an independent publisher until 1993, publishing postmodern stars including Donald Barthelme, Joan Didion, and Grace Paley, though Straus considered himself more Epstein's peer than obverse.

Meanwhile, most leading fiction writers published with conglomerates: Ann Beattie, Raymond Carver, John Cheever, Toni Morrison, Philip Roth, Anne Tyler, and John Updike with Random House / Knopf; Saul Bellow, Don DeLillo, and Thomas Pynchon with Viking.

The scene was especially bleak for those who were not white men. Even with Toni Morrison's advocacy for black writers at Random House, the conglomerates remained overwhelmingly white. New Directions was almost exclusively white.16 Grove, whose list was notoriously male despite some improvement in these years, continued to operate with exclusively male upper management and executive editors.17 By 1990, the radicalism of ethnic studies had been institutionalized as multiculturalism and the canon wars had been decided largely in favor of expanding the purview of literary history beyond white men. The conglomerates, along with New Directions and Grove, were out of step with higher education. Who would publish the multicultural literature demanded by the moment?

Nonprofits were well-situated, upon Schiffrin's firing and elevated anxiety about conglomeration, to take up fiction and to do so while taking advantage of the industry's limits and prejudices. As a panelist at the conference of the American Association of University Professors, Scott Walker predicted, "More and more serious books won't be published by the big commercial houses — their publication will fall to university presses and independent publishers, for whom the 1990s will be a time of tremendous opportunity."18

Walker spoke from self-interest, but he was right. Publishers Weekly, covering the American Booksellers Association's conference the next summer, reported, "It is as if, in 1991, a critical mass has been achieved, with the small press section now crystallized into what in recent years glimmered beneath the bookish surface as a possibility — a sidelines bazaar — with the main floor, this year commodious if not exactly airy, a temple to democracy in book publishing."19

Walker had positioned Graywolf at the forefront of the nonprofit boom. Its budget had "increased from $257,000 in 1986 to approximately $900,000 in 1991."20 In a grant proposal submitted in late 1991, Graywolf claimed, "many current funders of literature think that in the way the 1960s were in philanthropy the decade of theater, the 1990s will be the decade of literature."21 A big part of this growth involved building lists of literary fiction. Graywolf observed that conglomerates were "cutting back their fiction and literary publishing programs," and, as a result, Graywolf had been receiving "manuscripts from more established authors; from authors who deliberately choose to be published by a smaller house rather than a more commercial one; and it is now more possible to acquire books that have stronger sales potential."22

The timing was such that literary nonprofits without explicit commitments to ethnic literature, such as Coffee House and Graywolf, found themselves expanding their fiction lists as demand for ethnic literature was growing among government bureaucracies and the donor class. At a long-range planning meeting in 1991, Graywolf staff observed that fiction sales were down in general, but up for ethnic literature.23 One of the "goals and priorities" that year was to "aggressively broaden the range of potential funders to Graywolf, by making special efforts on behalf of books that treat social and educational issues."24 Above all, this meant marketing Multi-Cultural Literacy, an anthology of essays that intervened in the raging canon wars over what should be taught in high school and college. In August, Graywolf staff brainstormed "some sort of catchy slogan regarding GW's crucial role in this discussion: (i.e. along the lines of: 'Way before Dinesh D'Souza there was multiculturalism. Graywolf Press: we are the debate.')"25 By the end of the year, Graywolf expanded its mission to note that its "books often help to promote cross-cultural and international understanding."26 This meant they published books by writers of color and translations.

In a 1995 essay about her internship at Graywolf, Sherry Kempf made this logic plain. "One book on the fall list that highlights the interaction between marketing and funding," she wrote, "is Little by David Treuer."27 Treuer is a member of Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe who studied creative writing under Toni Morrison at Princeton. Little, published in 1995, was his first novel. "This type of project is fairly new for Graywolf, but it does fulfill the community outreach goals that funders are looking for right now. The book is written by a person of color whose own community will be served by the grant."28 Kempf summed up, "There seems to be a trade-off: non-profits can afford to take more risks, but in return they are required to comply with funding guidelines."29 State and philanthropic money freed Graywolf from surviving solely on sales and subsidiary rights but made the publisher beholden to the priorities of its funders, which, in the 1990s, meant, in large part, multiculturalism.

Allan Kornblum, publisher of Coffee House, was forthright. In 1994, he privately acknowledged that "Ironically, Coffee House has developed a reputation as a publisher of Asian American titles without that specific goal in mind. Through our usual process of selecting books that are diverse or adventurous and represent fine writing, we have 'discovered' or advanced the careers of a number of critically acclaimed Asian American writers."30 The next year, Coffee House would present itself in a grant proposal as a press that "takes very seriously its commitment to represent diversity. Over the years we have become known for presenting the voices of under-represented communities and maintaining high literary standards. We are one of the premier presenters of work by Asian American writers in the country."31

The press leveraged its multiculturalism to differentiate itself from the conglomerates. "Although commercial presses have published some high-profile books by writers of color, small presses have long championed literary diversity."32 This was selectively true. The proposal continues, "One year books by African American writers are the craze in the for-profit sector, another year books by Asian American writers hit the stands, but small presses stick with their commitment, providing the public with the full picture of the many cultures that make up America."33 This was how an accident became a mission. Nonprofits embraced multiculturalism less out of principle than convenience.

What did publishers' unstable mix of motives portend for multiculturalism? The meaning of multiculturalism was at stake. What would it mean to represent Asian American, Black, Indian, Latinx stories? Whose voices would be elevated? What kind of racial visions would result from the constraints that governed access to the public sphere? Nonprofits purport to operate with a freedom conglomerates lack. But patronage matters. Nonprofits need to please their funders because they return again and again to the same monetary well. And in these early years, their funders, consciously or not, had a vision of what multiculturalism meant to them. Ethnic literature is no stable thing. Every new book stakes a definitional claim. The sudden elevation of these literatures by nonprofits in the 1990s meant that a lot of new books by writers of color were creating the categories to which they were assigned.

What differences are there, if any, between the fiction that writers of color occasionally sold to market-driven publishers and that which they sold to the subsidized nonprofits? How did patronage, whether the market's, the state's, or the philanthropist's, shape these bodies of literature?

3: NEA

The Arts and Humanities Act, which founded the National Endowment for the Arts in 1965, named as its aim the reinforcement of American hegemony. "The world leadership which has come to the United States cannot rest solely upon superior power, wealth, and technology, but must be founded upon worldwide respect and admiration for the nation's high qualities as a leader in the realm of ideas and of the spirit."34 In principle, the US, during the Cold War, claimed to endorse aesthetic freedom as an extension of individual freedom — its "high qualities" — against USSR censorship and state-sponsorship of propagandistic art.

Alongside its service as handmaiden to America's global ambitions, the NEA served, according to Ralph Ellison, to shore up democracy at home. Ellison was an original appointee to the National Council on the Arts, the advisory board to the NEA. He made his case in the introduction to Buying Time: An Anthology Celebrating 20 Years of the Literature Program of the National Endowment for the Arts. (The book was edited by Scott Walker and published by Graywolf in 1985, just as the press was transitioning into a nonprofit with primary support from the NEA.)

Ellison describes the NEA as "a long-deferred answer to questions that had perplexed the nation's leaders for close to two hundred years: what role should the imaginative arts play in the official affairs of a democratic society?"35 But the Founding Fathers, in Ellison's account, weren't so much perplexed by the question as hostile to the idea that the arts might have any role at all. He writes that the "likes of John Adams and Benjamin Franklin" would see the workings of the NEA as a "drastic reversal" of their sensibilities.36 "For them," he writes, "the imaginative arts were an enhancement of monarchic culture that required an educated elite for their proper appreciation," which was what the Fathers were trying to escape.37 With the GI Bill and the postwar economic boom, the number of college-educated Americans exploded, changing the conditions for the government's relationship to art: suddenly the subsidization of art could look more democratic and less aristocratic.

Ellison does not defend the NEA because it provides aesthetic material for the educated class. He argues that art does the crucial work of lubricating the otherwise dangerous friction generated by the differences within American society. "By projecting free-wheeling definitions of the diversity and complexity of American experience it allows for a more or less peaceful adjustment between the claims of 'inferiors' and 'superiors' — a function of inestimable value to a society based, as is ours, upon the abstract ideal of social equality."38 Ellison celebrates art for its ability to resolve real inequality with symbolic projections. He makes a political argument for what Mark McGurl has dubbed "high cultural pluralism," literature that unites preoccupations with cultural difference and modernist aesthetics, a boon, thinks Ellison, for a nation ostensibly committed to social equality but divided by racism.39

Immediately upon its founding, the NEA feared that conglomeration threatened literature's diversity. As the NEA was getting up and running in the late 1960s, the publishing industry's first wave of conglomeration began its work of consolidation. The "literary ecosystem," in the words of the NEA's official history, "was undergoing significant change."40 The Endowment understood that it was dedicating "resources and funds to poets and fiction writers whose works might not survive in this new mass media climate."41 For most of its first two decades, the NEA offered small grants of up to several thousand dollars to writers and literary organizations, awarding nearly twelve hundred by 1985. In the 1970s, NEA grants were "the only national funding available to nonprofit literary presses," helping to pay for "paper, binding, and operating costs."42

Beginning in the 1980s, the NEA offered larger "challenge grants," which underwrote the rapid expansion of the nonprofits.43 The money was important, but even more important was how these grants compelled the improvement of business practices. The founders of the presses were often literary people who loved books but had little business acumen and muddled through with dodgy finances. As late as 1987, Graywolf — as revealed by an external audit — was tracking costs with cards for each book, but "not all job cost cards [had] been accumulating expenses on the same basis."44 Such chaos was typical.

To apply for a challenge grant, a press had to complete an extensive application, detailing how it intended to allocate the funds. If awarded, the press had to maintain an account of how, in fact, the funds were spent and to what end, which instilled discipline. Coffee House's Allan Kornblum had to ask, when applying in 1988, "What is our optimum size...in terms of staff, and number of books to print, and number of copies of each book? What percent of our budget can we afford for rent, for marketing?"45 By the end of the 1980s, Jim Sitter, a literary impresario who did more to establish the nonprofits than anyone, "began leading a concerted advocacy effort on behalf of literary presses in the private philanthropic community."46 Two foundations — Wallace and Andrew W. Mellon—began offering large grants "to help presses market more effectively (Wallace) and build organizational capacity (Mellon)."47 Repeated across the nonprofit publishers' archives is the same gratitude expressed by Emilie Buchwald, founder of Milkweed Editions: "Funders didn't give us just money, which was important; they gave us expertise and they left us with infrastructure."48

Between 1984 and 1994, Graywolf expanded dramatically. Graywolf won a challenge grant in 1984 with the backing of the director of the NEA's Literature Program, Frank Conroy (who would leave the NEA in 1987 to lead the Iowa Writers' Workshop). Conroy wrote Walker a letter of recommendation in which he called Graywolf "a model press, a paradigm" and insisted that, "Graywolf must expand. Over the next decade the very best of the independent presses must publish the literary writers whom the conglomerate-dominated commercial publishers can no longer support."49 He closed, "Graywolf is the future."50

Also in 1984, Graywolf became a nonprofit and, soon after, moved from Port Townsend to Saint Paul to take advantage of Minnesota's vibrant philanthropic scene. Walker established "a minimal Board of Directors" — a requirement for nonprofits — with two members: Raymond Carver, who, by then, was widely considered the country's best short story writer; and Jonathan Galassi, a well-respected editor at Random House who went on to become the president of FSG.51 Graywolf won Mellon and Wallace grants. Its list and budget grew, but not without turmoil. From the outside, it appeared to be thriving, but Walker was increasingly unhappy. For years, he'd been asking James Laughlin how he'd managed to have success while spending so much time away from New Directions. (Laughlin was independently wealthy.) In early May, 1991, at the end of another long Minnesota winter, Walker wrote Laughlin, "I want very much to leave Minnesota, to move into the Rockies, I need to be nearer mountains. But I don't want to hurt the press, and a lot of people close to it are skeptical that I'll be able to live away from Graywolf and for things to keep working well. I point to ND as an example of how it can work."52

But even as it was, things were not working. By early 1994, Graywolf was in serious financial trouble. In March, the board of directors asked Walker to resign, which he readily did, acknowledging his managerial struggles. After an extensive search, the board hired Fiona McCrae. She was a perfect choice. She had experience at Faber and Faber, a literary commercial publisher, but had grown disillusioned with the for-profit scene and had left her position with the thought of becoming an agent. She brought not only business sense but invaluable professional networks from east coast publishing. One of her first acts was to meet the important players in the nonprofit world, including Gigi Bradford, the current director of the NEA's Literature Program. In McCrae's first letter to the Graywolf community, she reported that, at her meeting with Bradford, "the mood was high, with an optimism that the field was recognizing itself and therefore finally able to become stronger."53 Succession is a thorny problem for a small press because the founder's vision, even his identity, is profoundly embedded. Graywolf set an early example for how to make it work.

By 1994, after a decade of incubation, nonprofit presses comprised a new formation, a "field," built hand-in-hand with the NEA to resist the claustrophobia brought on by conglomeration. It included countercultural figures like Coffee House's Allan Kornblum and Milkweed's Emilie Buchwald, who got their start with boutique letterpresses; political and aesthetic activists like Arte Público's Nicolás Kanellos, Feminist Press's Florence Howe, and Dalkey Archive's John O'Brien; and expatriates from conglomeration like McCrae and André Schiffrin (who had, by then, started his own nonprofit, The New Press). Such figures pooled their resources for the benefit of all.

Two keywords defined the field's self-understanding: literary and diverse. Nonprofits used these words to differentiate themselves from commercial presses and the homogenizing force of conglomeration. This narrative of literature in crisis was habituated and institutionalized through the perennial documentation required by state and philanthropic funding. Crisis was good for literature because that made the mission of the nonprofits — to sustain literature's otherwise endangered diversity and literariness — urgent. Conversely, claims to having successfully implemented multiculturalism gave the impression to readers that the literary world was more diverse, equal, and democratic than it was. The celebration of Sandra Cisneros, Louise Erdrich, Toni Morrison, and Amy Tan masked the profound whiteness of the industry.54

What did this narrative of crisis mean in practice for the nonprofits? It offered an aesthetic agenda with regard to content — "multiculturalism" — and form — "literary" style — language they used not only to win grants but, then, to justify editorial decisions. Yet this narrative opens up further questions, because its terms are vague. What did it look like when the nonprofits translated the cant from their grant applications into published literature? What did it mean to be literary and diverse?

4: Modeling Literariness

Nonprofit publishers claim that by escaping the strictures of the market they can publish writing that is more literary than what the conglomerates issue. Literariness is a contested category. Some, after the high modernists, New Critics, and deconstructionists, argue it names the unique style that separates literary from genre or mass-market fiction.55 Others argue that literariness has more to do with sociology than with the text itself: that is, literariness resides in the extratextual act of claiming separation from the demands of the market. Nonprofits perform the latter; the claim creates its truth in the act of declaring it: literature published by nonprofits becomes, by definition, literary. But is there truth to the former? Is there anything in the text that distinguishes nonprofit fiction from that of the conglomerates?

It's difficult for us to tell. Even if we could read a substantial fraction of the conglomerate novels published in recent decades — which we can't — and compare them to nonprofit novels, we wouldn't be able to forget the authors or imprints, muddying our evaluation. What we need is a method that can attempt to distinguish between conglomerate and nonprofit novels solely on the basis of stylistic features. Recent developments in computational modeling and machine learning allow for that: namely the method of text classification via logistic regression, advanced in literary and cultural studies by Richard Jean So, Ted Underwood, and others.

Supervised learning algorithms work like this. Everyone with email relies on text classification to separate spam from legitimate emails. Email providers train models to recognize the difference by giving them emails labeled "spam" and others labeled "not-spam" and asking the model to learn the features that most reliably distinguish them, which could include a preponderance of all-caps, or phrases like "free money" or "get paid." Those who design the model decide which features it should take into account, which could be limited to single words, or could include punctuation, capitalization, phrases, and elements of syntax. They also decide which documents and how many of them the model will be trained with. They test the model by giving it unlabeled emails and asking it to distinguish them. If the model can do it accurately a high percentage of the time, that's a good spam filter.

We built a model and determined whether it could distinguish between conglomerate and nonprofit novels. (Technical details are in Appendix A.) On what basis is the model making its distinctions? What does a novel look like to the model? We trained the model to see novels in terms of diction. It searches for which words are used, and how often. This is a crude approximation of how humans encounter novels. If the model, on this basis, can't tell the difference between conglomerate and nonprofit novels, the result doesn't prove that there's no difference between them, just that there's no difference that a computer can discern on the basis of diction, or maybe that the model was too weak because of insufficient or imprecise training data. But if the computer can tell the difference, all it needs is this approximation to show a categorical distinction — a distinction that ought to get clearer with more sophisticated features.

We relied on HathiTrust to construct the conglomerate and nonprofit corpora. HathiTrust is a digital library that holds millions of volumes from dozens of research libraries, including volumes under copyright. In September 2018, HathiTrust opened its collections to scholarly use. We accessed the volumes through a virtual machine on our computers, performed computational analysis, and exported the results. The copyrighted volumes remain secure. The nonprofit corpus contains all 191 novels that Hathi holds from Coffee House, Graywolf, Milkweed, and Mercury House. We chose these four because they have published continuously across the period, they define themselves as literary, they publish novels, and they publish authors of diverse race and gender. The conglomerate corpus contains 606 Random House novels. We chose Random House because it is the largest trade publisher and has long served as a primary example against which small presses define themselves. Both corpora span 1980 to 2007.56

Before we started, we had no idea whether the model would be able to tell the difference between the two corpora. Based on our experience reading novels from both categories, it was unclear to us whether they were different in ways detectable by a machine. The model should, as with a coin flip, be right 50 percent of the time. It is right about 66 percent of the time. This is not an excellent rate, but it is much better than random. "Conglomerate" and "nonprofit," definite categories for a novel's provenance, ought to be imprecise as indicators of a novel's diction. That our crude model would be enough to accurately predict classes 66 percent of the time impressed us. If it were much better than this, we would be concerned. Given the imprecise science of title acquisition, the idiosyncrasy of editorial habits, and the circulation of staff and authors between conglomerates and nonprofits, we expected at least some overlap and blurriness.

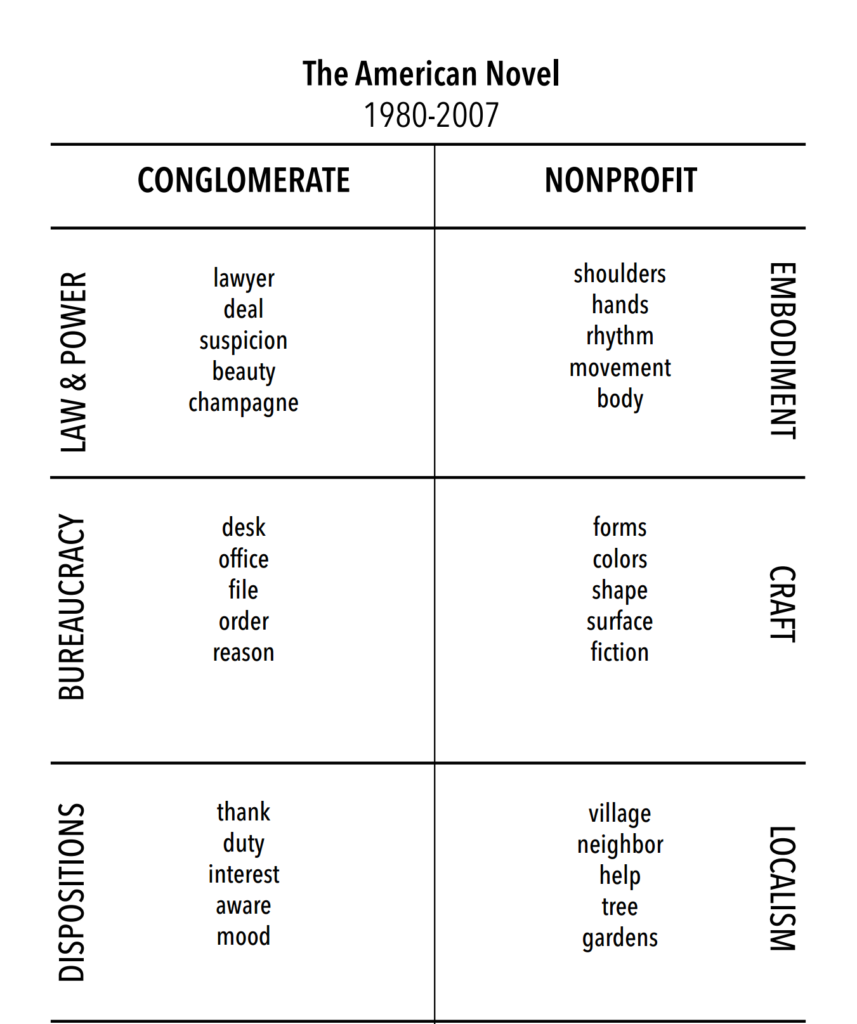

The model shows that conglomerate and nonprofit novels differ at the level of diction. Is the difference a matter of "literariness"? One affordance of our machine learning model is that it records the features that most reliably distinguish between classes. It gives every word a weight that it uses to classify the novels. Here are the words that most differentiate the categories.

Extensive results are available on GitHub. But a glance is enough to notice the coherence of the nonprofit features and how they differ from those of the conglomerates. These are terms of embodiment (shoulders, hands, feet, rhythm, movement, washing, jumping playing, catch, grab, beat, gesture, break condition, sweat, swollen, dizzy, hunger, body), craft (fiction, stories, forms, focus, show, shows, colors, shapes, surface, invisible, portrait), and localism (village, neighbor, doorway, visited, roads, help, care, provide, tree, forest, roots, planted, fruit, gardens, pig, chicken, bird, feeding).

The conglomerate features require a bit more interpretation. To be frank, the categories presented in the image above are just that — an interpretation, open to contestation by others observing the evidence. As with the nonprofit features, we have split them into three groups. The first demarcates a world of law (lawyer, expert, deal, judge, court, law), suspense (murdered, weapons, suspicion, demanded, horror, risk, danger), and power (affair, deal, champagne, party, waiter, hotel, airport, confident, ease, beauty, handsome, senior). The second signals bureaucracy (desk, office, meet, meeting, meetings, message, reports, file, manager, company) and form, in the sense of order, logic, and pattern (order, reason, rule). The third names dispositions and mores of polite society (yes, thank, duty, actually, private, interest, lunch, aware, quietly, welcome, sir, suppose, mood).

We built this model to ask whether nonprofits are, as they claim, more literary than conglomerates. The results allow us to extend recent computational studies into literariness and answer yes.

Ted Underwood has shown that fiction differs from nonfiction by its use of "action verbs," "body parts," and "verbs of sensory perception."57 Andrew Piper, in a separate study, shows that the "particular nature" of fiction is its commitment to our "perceptual" engagement with the world, "grounded in an appeal to an embodied encounter."58 The divergence between fiction and nonfiction has grown over time. In the 1700s — the early days of the English-language novel — fiction was closer to biography, but, across the centuries, they have grown farther apart. After 1980, nonprofits took responsibility for literature of embodiment, providing continuity with this several-century trend. Embodiment goes together with pastoral neighborliness (a world of simple things close to hand: tree, fruit, pig, gardens) and concern for craft (the foundation of art and experience: forms, color, shapes, surface) corroborating continuity with the past.

Is fictionality the same as literariness? In a broad sense, all fiction is literature and what marks it as such ought to be named literary. But literariness is also often used to demarcate literary fiction from genre writing. In this sense, nonprofit fiction, as opposed to that of conglomerates, is literary because it does not mark itself with a clear genre signal, but rather doubles down on what is distinct about fiction: language of embodiment. It even winks at doing this with its attention to craft, not least fiction and stories themselves. These results lend credence to a definition of literariness: fiction that emphasizes what distinguishes it as fictional.

The language of conglomerate fiction is different, less about embodiment. It invites speculation that an autopoietic process is at work in which the conditions of production, that is to say, conglomeration, make their way into the text itself. And not just any conditions of conglomeration, but specifically: a kind of bureaucratic formalism, rule, system, order, office, desk; a results-driven world of ambition and power, party, hotel, spend, beauty, handsome, champagne, deal, power, hundred, thousand, million; and the language of correspondence, acquisition, and rejection, thank, hope, yes, smiled, interest, lunch, decided. We might see these three modes as allegorizing the processes that one of us has argued elsewhere define the conglomerate era: rationalization, the bottom line, and the rise of the agent.

There is something science fiction-y about this, as if authorship works at multiple scales, as if the many minds cooperating within modern bureaucracy to bring a book to print compose, beyond their will, a collective agency. Maybe even a collective authorship.59 Conglomeration expresses itself as systematic, nonprofits as fleshy. Machine, body. Contemporary literature has a dualism.

This — that there's systemic conglomerate allegorizing and nonprofit literariness — is a hypothesis. It is the most persuasive interpretation when looking at the evidence presented by our model. But these are only the most significant words, the influential tip of an iceberg, and they are dispersed across hundreds of novels and thousands of contexts. We need to return to close reading to understand what conglomerate form looks like at the scale of the sentence, the paragraph, the chapter, the novel. And to answer not only the question what does it mean for nonprofits to be literary, but also, what does it mean for nonprofits to be diverse?

5: Close Reading and Race

The fiction lists of Coffee House, Graywolf, and Milkweed are more diverse than those of the conglomerates in terms of race and gender. Collectively, 70% of the nonprofit authors are white. 93% of the Random House authors in our corpus are white. Moreover, white men account for more than half of authors at Random House, whereas they make up less than a third of authors at the non-profits. But the nonprofit lists are small enough that one or two writers can account for a big share of the diversity. As we write, Percival Everett has published nine novels with Graywolf from its list of ninety-one. Karen Tei Yamashita has published six novels with Coffee House from its list of one hundred and twenty-two.

As we'll see, introducing Everett and Yamashita in terms of diversity is misleading. The writers represented by these statistics — who serve these presses in part as statistics — resist them through their work.

Sometimes our model correctly recognizes Everett's and Yamashita's novels as nonprofit, other times it misclassifies them as conglomerate. For each novel, the model gives not only a binary yes or no, but also a percentage along a continuum between nonprofit and conglomerate. To better see what this means, to gain a sense of the model's sensibility, consider that it fiercely and rightly thinks that Michael Crichton's Rising Sun, Richard North Pattersons's Degree of Guilt, and Mario Puzo's The Fourth K are conglomerate novels. These are all plot-driven blockbusters. The model is rightly sure that George Rabasa's Floating Kingdom, Lewis ("Scooter") Libby's The Apprentice, and David Treuer's Little are nonprofit novels. These novels are classically literary.

The model wrongly believes that Brian Evenson's The Open Curtain, Percival Everett's Wounded, and Gilbert Sorrentino's A Strange Commonplace are conglomerate novels. It is wrong in the opposite direction about Toni Morrison's Beloved, Maxine Hong Kingston's Tripmaster Monkey, and Michael Ondaatje's In the Skin of a Lion, believing them nonprofit.

Each of the novels listed deserves fuller treatment than we can provide here, to be read through the terms that distinguish between categories.

We will investigate a borderline case. What does it look like when a novel straddles two classes? The model is uncertain about Everett's Frenzy. It gives the novel a 66% chance of being published by a non-profit, although that number fails to achieve statistical significance. Based on variance in the data, our model wouldn't be surprised if Frenzy turned out to be published by a conglomerate after all. In fact, out of four Everett novels in the corpus, Frenzy is the only one the model guesses correctly, in spite of its low confidence. This is our draw to Frenzy, it is an outlier in a body of work by an author who troubles the model.

The model's ambivalence about Everett's novels is not surprising. We found that the model's accuracy (recall) varies across authorial identities. For example, it is especially good at identifying when a novel by a woman of color was published by a non-profit. But among novels by Black men, the model is equally good — or rather, equally ambivalent. Its accuracy on novels by Black men is only 50%, and that is true for novels in both categories of publisher. In sum, we found that the model's chief biases, based on race and gender, are destabilized by novels of Black men generally, and that Frenzy poses a particular challenge.

The novel is a riff on Greek myths. It begins with the king of Thebes facing a crisis. Dionysus, god of wine, has wooed the women of Thebes to abandon the city for the frenzy of the wilderness. The blind prophet Tiresias tells the king, "They have gone to beat the loose-skinned drum of life and power, leaving your city, shall we say, male."60 Or, as Dionysus explains, "These men in power, their eyes see too far and their hands are too large for close work. Their hands are numb from the counting of money. That is why these women come to my call. These women have nothing to count but their fingers."61 Everett, like our model, genders language of embodiment: whereas men are alienated from their eyes and hands, women attend to their fingers; women beat drums. Power tends to signal conglomeration by our model; here it is what is contested.

Meanwhile, the king's mentor teaches him Nietzschean philosophy. "Power is preliminary to all things and preontological"; "you will thank me for a hardness"; "there is no such thing as misrule as long as you rule."62 If the wilderness is a site of feminism, embodiment, and frenzy, then the city is the site of patriarchy, wealth, and absolute rule.

The bolded words are influential according to our model, indicating nonprofit if italicized and conglomerate if underlined. Everett has staged a struggle between city and wilderness, patriarchy and feminism, form and frenzy, wealth and embodiment, conglomerate and nonprofit. The novel is difficult for the model to identify because it enacts the division of the model itself, the division of the contemporary publishing industry.

The novel bears this out. The binary terms accumulate and expand. The king thinks, with regard to Dionysus, "this she-boy-god who dances so lightly is only as old as me, but he will live forever; so much to envy."63 The king's mentor complains that, in the city, "there is no production" and "trade has ceased."64 He declares, "Reason is required for the derivation of actions from laws. Out there in that wild, away from my city, where our women frolic and make sick love, reason has no residence, the rabble move irrationally, forgetting rules, axioms, and precepts."65 The city is host to economics and reason, "untidy and cold," the narrator tells us, "vacuous and full of echoes and promises and ambitions and prevarications."66

Away from the city, in the wilderness, rhythm holds sway: "breathing and song, rhythmed by the drum"; "the distant drum that fed the rhythm"; "the rhythm of the drums"; "the endless swaying—I continue to feel the rhythm of it"'; "drummers among them keeping rhythm."67 The wilderness is a world of heightened embodiment, of drunkenness, sex, and violence, of naked dancing, of killing and eating deer raw.

Everett encourages us to side with Dionysus. The stakes are freedom. Freedom from money and order and the dispositions of polite society. Freedom to live in one's body. Freedom of speech. The king's mentor brags, "I gave these Greeks their letters."68 But so long as the women were bound by the city, they could not properly speak. By leaving for the wilderness, Tiresias says, they "will rend their tethers and seek their own voice."69

Frenzy is an allegory for the plight of the writer in the conglomerate era. To speak in the city is to be subject to the rationality and instrumentality of capital. To speak in the wilderness is to submit oneself to the embodiment of frenzy. But the binary, in Everett's vision, cannot hold. The leader of the women is tricked into believing that, in the chaos of drunkenness, she has killed her own son, which convinces her and the women to quit the frenzy and undergo "a morose, sullen procession back into the city, a sullen defeat."70 Embodiment as resistance to capital, Everett concludes, is futile; nonprofits, too, must submit to capital. The writer must skillfully navigate between rhythm and reason, embodiment and bureaucracy.

Where's race? Frenzy is, among other things, an allegory for the patriarchy of publishing. But this was the 90s and multiculturalism was king. And Everett was Graywolf's black writer.

Everett addressed race with Erasure, published in 2001 (with the University Press of New England and, in later editions, with Graywolf) — a direct outgrowth from how booksellers treated Frenzy. Fiona McCrae, Everett's editor at Graywolf, writes: "that a major chain chose to display [Frenzy] only in the African American studies section surely sowed the seeds of anger that gave rise [to] Erasure.71 Everett was furious that booksellers pigeonholed him as a black writer with a book that, in his estimation, had nothing to do with race.

Erasure features Thelonious Ellison, who, like Everett, is a fiction writer and an English professor in southern California. Ellison describes an encounter with a literary agent at a party in New York. The agent tells Ellison that he "could sell many books if [he'd] forget about writing retellings of Euripides and parodies of French poststructuralists" — both of which Everett has done — "and settle down to write the true, gritty real stories of black life."72

Ellison considers dropping his agent because of the agent's unhappiness with the fact that Ellison's work is "not commercial enough to make any real money"73 "The line is, you're not black enough," his agent tells him.74 In need of money to support his ailing mother, Ellison writes a hyperbolic parody of Richard Wright's Native Son and calls it My Pafology, though he later retitles it Fuck. Fuck, written under a pseudonym, becomes a commercial success, and Erasure concludes with Fuck winning a major literary award, granted by a committee on which Ellison is a member, horrified by the depth of his colleagues' gullibility.

Erasure extends Everett's critique of authors' complicity with markets under conglomeration. In Frenzy, authors navigate between the literariness of embodiment and allegories of conglomeration; in Erasure, the Scylla and Charybdis are the expectations placed on writers of color in a time of multiculturalism to represent their race. One can play the game and submit to stereotypes or refuse and be conscripted against one's will. Erasure argues that conglomerates publish books by black authors that confirm prejudices that readers bring to books by black authors. It argues that the industry wants books by black authors that already read as black.

Everett portrays a publishing industry in which agents, editors, booksellers, reviewers, academics, and writers are all complicit in conflating fiction with the authentic experience of race. Literary markets in the era of conglomeration shaped what the public understood as blackness according to a liberal multicultural fantasy of authenticity that sold.

Everett complained about this situation to McCrae a few months after Frenzy came out, several years before the publication of Erasure. "Sadly, it seems that the publication of black writers is confined to that material which deals with what the culture wants to understand as 'being black.' It being the case that black writers can only know, and further only comment on, what it is to be black or non-white. As you know, my work does not tend toward this."75 "To hell with markets," he adds, squarely placing blame on commercial publishing and, he imagines, signaling his solidarity with the nonprofit world. But, as the end of Frenzy suggests, he makes the more sophisticated observation in his fiction that he must abide by certain market demands, even with nonprofits. "I do not want to feed complacent expectations, but I do want to be entertaining enough to lure a reader into something new — if not a new way of thinking, then a new way of reading."76 Frenzy and Erasure end in defeat at the hands of markets. But Everett hopes for a negative dialectics: that, in their negation, the novels will awaken readers to a new consciousness.

Close reading Percival Everett reveals a struggle — embedded in his sentences, his characters, his plots — between author and institution. Ironically, Everett fails to recognize that Graywolf and its fellow nonprofits operate according to a parallel racial logic as the conglomerates, one the image of the other in a funhouse mirror. He praises Graywolf as exempt because it publishes him, when, for Graywolf, he serves as an ideal vessel for its own mission of liberal multiculturalism, a prized commodity for its niche markets. Although it contradicts his stated motives, Everett's literary project could be read not to condemn markets, but to condemn those markets that propagate inauthentic and constraining racial fantasies; the novels, that is, espouse one more liberal multicultural vision.

6: Multiculturalism and the Market

How has conglomeration shaped multiculturalism? How does the conglomerate-nonprofit divide — the mechanical versus the embodied — influence representation along axes of inequality?

Everett gives us one possible, if cynical, answer: that conglomerates, in submission to the market, publish writers of color who reproduced popular stereotypes. These writers, Everett argues, are purveyors of internalized racism. In Erasure, this position belongs to Juanita Mae Jenkins, a young middle-class woman who graduated from Oberlin before publishing a celebrated novel in black dialect. Everett has Alice Walker in mind. ("I have never in my life heard someone say, 'Where fo' you be going?'," he said in an interview. "So Alice Walker can kiss my ass."77) He blames Oprah. In Erasure, an Oprah figure launches Jenkins to fame. And in that same interview, he says, "Oprah should stay the fuck out of literature and stop pretending she knows anything about it."78

Nonprofits provide the requisite condition for true art. Everett wrote to McCrae, "What you and Graywolf have done is allowed me the freedom to write as an artist. To my mind there is nothing more politically significant than for a press to actually free itself, and therefore the artists it shelters, from the noxious political traps this culture lays for its 'writers of color.'"79

Everett's account rings false. Consider the range of conglomerate multiculturalism, which includes Sandra Cisneros, Edwidge Danticat, Louise Erdrich, Maxine Hong Kingston, and Toni Morrison. The politics of market-friendly representations of people of color cannot be reduced to internalized racism. In a more charitable moment, Everett acknowledges that Morrison "could write anything down and get it published because she is going to make somebody some money. It's also obvious that she doesn't do that."80 Conglomerates compel books to make profits, demanding market-friendly representations of race, but writers develop strategies to create aesthetically compelling visions of race within those constraints. Paul Beatty and Mat Johnson have built careers, over the past few decades, writing satires of racial discourse in market-friendly styles that sell for conglomerates and dismantle Everett's position.

Unlike conglomerates, nonprofits have explicit social missions that guide acquisition. As such, writers of color comprise a higher percentage of their lists, but, because they are much smaller than conglomerates, this amounts to relatively few books. They tend to be critical of mainstream representations of race, in two senses: they criticize them, and they explore the conditions of their possibility, asking, like Everett does in Erasure, how is it that we see race as we do? In the essay collection Native American Fiction, Graywolf-published novelist David Treuer argues, along similar lines to Everett, against essentialism and stereotypes in American Indian literature. Some nonprofit novels depict people of color who evade stereotypes because they are middle class or culturally refined, such as those of David Haynes, published by Milkweed, or Clifford's Blues by John A. Williams, reprinted as part of Coffee House's Black Arts Movement series. The title of that series is ironic, as its books include some that, because they veered away from an essentialism central to the Black Arts Movement, fit uneasily within it. Other books in the series, including William Melvin Kelley's dem and Kristin Lattany's The Lakestown Rebellion, similarly embrace non-essentialist depictions of race.81

Karen Tei Yamashita's work exemplifies the critical tendencies of nonprofit multicultural fiction. She sent Through the Arc of the Rainforest to Coffee House in 1989. Allan Kornblum reported, "I couldn't believe I had a novel that exciting sitting on my lap in manuscript."82 It became Coffee House's first hugely successful novel (by nonprofit standards), selling out a first run of 4000 copies in three weeks. Coffee House sent Yamashita on the press's first major author tour. She has gone on to publish seven books with Coffee House, including the National Book Award finalist, I Hotel.

Yamashita's first two novels, Arc and Brazil-Maru, are set in Brazil with Japanese protagonists. "The centrality of Brazil to Yamashita's creative work," Kandice Chuh writes, "immediately marks its eccentricity to the usual regimes of U.S. American literature."83 By the mid 1990s, "Asian Americanist literary discourse ha[d] only loosely become a home for Yamashita's work."84 Critic Rachel Lee felt the need to attempt a "rapprochement" between Yamashita's early novels and Asian American literary studies.85 Arc was published in 1990 and Brazil-Maru in 1992, as the nonprofit movement was attaining liftoff and multiculturalism was the way forward. Coffee House wrote to one of its funders that "we have been encouraging Ms. Yamashita to take up the subject of Asian/Black relations in Los Angeles. We look forward to publishing this yet-to-be-written re-envisioning of the city of dreams."86 Such a book would neutralize Yamashita's eccentric geographical predilections and situate her securely among multiculturalism.

In 1997, Coffee House published that book, Tropic of Orange. It is, as promised, an LA novel. It has seven sections, one for each day of the week beginning on the summer solstice. Each section has seven chapters, one for each protagonist. The cast includes Asian American, black, and Latinx characters. Yamashita self-consciously embraces Gabriel García Márquez's magical realism and LA's noir tradition from Raymond Chandler to Walter Mosley. Literary critics have classified the novel as environmental, hemispheric, infrastructural, global, planetary, postmodern, science fiction, slipstream, technomodernist, and Asian American.

It is also satire. It pays homage to Nathanael West's acerbic LA satires by name-dropping Day of the Locust.87 And one of the principal objects of Yamashita's satire is multiculturalism. Emi, an ambitious and irreverent Japanese-American TV producer and loose avatar for Yamashita, is the character through which this satire flows. Yamashita introduces Emi by noting that she's dating her lover "because he was Latino, part of that hot colorful race," only to discover that "he wasn't what you call the stereotype."88 As for herself, Emi is "so distant from the Asian female stereotype — it was questionable if she even had an identity."89 In case she hasn't announced her position clearly enough, Yamashita adds that Emi "liked trying to be anti-multicultural" around her lover. "Right in the middle of some public place, she might burst out, 'Oh you're so Chicano!'"90 The third section, "WEDNESDAY," is subtitled, "Cultural Diversity." In Emi's chapter, she makes a scene in a sushi restaurant. Surveying the diners, she tells her lover, "Here we all are, your multicultural mosaic."91 After speculating about the provenance of those in this mosaic, she declares, "Cultural diversity is bullshit."92 She asks the sushi chef, "Don't you hate being multicultural?" adding, "I hate being multicultural."93 With this, Emi provokes the presumably white woman next to her who primly queries, "Whatever is your problem?" and goes on to defend herself against Emi's accusations. "I happen to adore Japanese culture. What can I say? I adore different cultures. I've traveled all over the world. I love living in L.A. because I can find anything in the world to eat, right here. . . . A true celebration of an international world."94

In a novel solicited by Coffee House to satisfy the hunger for multiculturalism, Yamashita proffers an explicit critique of multiculturalism as — in anticipation of Everett's Erasure — reinforcing and profiting from stereotypes packaged as cultural commodities that appeal to white consumers.95 She rejects liberal multiculturalism to endorse leftist, anti-globalization politics and radical hospitality toward the homeless.

The novel culminates in a lucha libre fight on the US-Mexico border between SUPERNAFTA and the novel's hero, Arcangel, in the guise of El Gran Mojado, which translates to The Great Wetback. Arcangel declares "I do not defend my title for the / rainbow children of the world. / This is not a benefit for UNESCO. / We are not the world. / This is not a rock concert."96 Arcangel is not on the side of attempts to mollify the inequities of global capitalism through the culture industry (UNESCO, USA for Africa). Even still, Arcangel's spectacle of lucha libre is complicit with the culture industry: "The audience, like life, would go on. . . . Somewhere the profits from the ticket sales were being divided."97 Yamashita deflates triumphalism about the political good of cultural protest. She indicts Coffee House's embrace of liberal multiculturalism at the same time that she knowingly acknowledges that her novel will advance that cause.

Over the next decade, Yamashita went from criticizing multiculturalism to pursuing its conditions of possibility, the sources from which it came, researching the rise of ethnic studies and the Yellow Power movement. This entailed a tonal shift toward earnestness and culminated, in 2010, in the publication of I Hotel, a novel comprised of ten linked novellas, one for each year between 1968 and 1977.

How she understood her identity changed. "For a while I thought I'd better be a Japanese American writer, or even a Nikkei writer since that would be the most accurate description of my background," she said in 2018, "but now I think of Asian American as being more appropriate.98 In the Afterword to I Hotel, she presents the novel as an "offering," a deeply-researched attempt to understand her predecessors, "the literary and political movements" that made her career possible.99

She attempts to reconcile a rift between two of the most prominent of those predecessors, Maxine Hong Kingston and Frank Chin, which is also a rift between conglomerates and nonprofits. The title of I Hotel's 1971 novella is Aiiieeeee! Hotel, which refers to the groundbreaking Aiiieeeee: An Anthology of Asian-American Writers, published by Howard University Press and edited by Frank Chin among others. For the expanded 1991 edition, Chin wrote an introduction that indicted Kingston, a Random House author and one of the most acclaimed and widely-read Asian American novelists, for pandering to white audiences with her alleged internalized racism and stereotyped representations. Chin was also an acclaimed writer whose widely-read novel Donald Duk was published in 1991 with Coffee House. Chin and Yamashita together propelled Coffee House's reputation in the early 1990s as a premier purveyor of Asian American literature — the accident that Allan Kornblum made a virtue.

Chapter Four of Aiiieeeee! Hotel, "War and Peace," is a series of sketches of Chin and Kingston by Sina Grace. Each of the chapter's seven pages displays a sketch of him next to a sketch of her. There is no text in the chapter beyond brief captions. They are described progressively as "Son / Daughter," "Sister / Brother," "Chinaman / Chinawoman," "Dragon / Dragon," and "Patriarch / Matriarch."100

Yamashita positions Chin and Kingston's dispute as familial (son, daughter, sister, brother) and the two of them as equals who, together, have shaped Asian American literature and ought to be treated with the respect owed to elders (patriarch, matriarch). Amid these portraits, Yamashita and Grace insert sketches of the pair as characters from the other's books. Chin is depicted as Wittman Ah Sing, a character from Kingston's Tripmaster Monkey possibly based on Chin; and Kingston is portrayed as Pandora Toy, a character from Chin's Gunga Din Highway, possibly based on Kingston in retaliation. Both are thinly veiled attacks. Yamashita captions these sketches "Fake."101 On the opposite page, Kingston and Chin are depicted as autobiographical characters from their own books, Fa Mulan from Kingston's The Woman Warrior and Kwan Kung from Chin's Donald Duk. These are captioned "Real."102 Yamashita asks the two to put down their arms, attempting to broker peace between these major figures of Asian American literature.

Yamashita rejects Chin's accusation that popular Asian American literature panders to whites and is racist. But she also embraces Chin, her fellow Coffee House author. She hopes to move beyond a politics of representation trapped in the terms of multiculturalism — the politics she had engaged and critiqued in Tropic of Orange. She settles disputes internal to Asian American literary identity to advance a new position, which she presents through her depiction of an Asian American Marxist reading group. The discussants historicize Asian American identity, observing that they became Asian Americans in 1966 through a process of racialization that they embraced as a "political designation."103 The discussion leader says, "you are organizing around this designation, and that's useful, but you are going to have to scrutinize it through a Marxist analysis that includes class."104 Yamashita's ambitious vision, in I Hotel, is to perform, in the tradition of Marxist dialectics, various syntheses: Kingston and Chin, popular and virtuous, conglomerate and nonprofit, race and class. She was rewarded by becoming a finalist for the National Book Award.

7: Conclusion

In 2008, Zadie Smith imagined "Two Paths for the Novel": lyrical realism in the long tradition of Balzac and Flaubert; or avant-garde, along the more recent model of Barthelme, Gaddis, Pynchon, and Wallace. (She voted for the latter.)

The next year, Mark McGurl published The Program Era, about how creative writing programs changed American literature. The editors of n+1 responded by proposing that the two paths for the novel were MFA or NYC: creative writing programs or New York publishing. MFA: Ann Beattie, Raymond Carver, Stuart Dybek, Deborah Eisenberg, Denis Johnson. NYC: Jonathan Safran Foer, Jonathan Franzen, Nicole Krauss, Gary Shteyngart.

Both Smith and n+1 tell partial truths. By missing corporate conglomeration, they miss the whole. The two paths paved by the period — which subsume and reorient realism or avant-garde, MFA or NYC — were commercial or nonprofit.

1980 marked the start of this era. Under tremendous financial pressure, commercial and nonprofit publishers split in their approaches to literariness. Viewed at scale, we see patterns emerge. The conglomerates produce allegories for themselves. Language of ambition, bureaucracy, and social mores differentiates conglomerate books from those of the nonprofits. And the nonprofits double down on what distinguishes fiction from nonfiction: language of embodiment. We must consider more than the name on a book's cover if we want to discern its contents: agents, editors, and marketers determine the discourse, though they disappear in most discussions of literature.

But if we zoom in to the scale of a single book, the view changes, returning some agency to the author. An author has considerable leeway in leveraging the discourse acceptable to her press. This negotiation between an author and the institution is almost entirely subliminal for everyone involved, happening at the level of intuition.

Writers of color, who make up a disproportionately small fraction of literary production, do not align easily along the intersecting axes of conglomeration and literariness. Works by leading conglomerate writers of color — Sandra Cisneros, Maxine Hong Kingston, Toni Morrison — are sometimes misclassified by our model as nonprofit books. Percival Everett's and Karen Tei Yamashita's novels are sometimes misclassified in the other direction. Rather, conglomeration organizes writers of color by how they respond to diversity. Everett and Yamashita, writing for presses with multicultural missions, make explicit, in their response, their refusal to play the role of writer of color passively. We have focused in this essay on authorial strategies of writers of color working with nonprofits. What are the narrative and stylistic traits of conglomerate diversity? How do Cisneros, Kingston, and Morrison adapt to the systemic discourses of their conglomerate milieu? These are questions for further study.

This literary order — organized around conglomeration, literariness, and diversity — lasted twenty-seven years, from 1980 to 2007. It ended with the financial crisis and the emergence of Amazon as a major player in publishing.

In 2003, Graywolf broke from the indie distributor that connects small presses across the US to partner with Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. "It is a step away from the band of 'small presses' and into that virtually empty gap between us and the substantial independent/literary presses," McCrae told her staff.105 The move gave Graywolf more visibility and clout at the cost of resentment from the small press world. It now occupies that "empty gap." Another study will need to survey the nonprofit world after 2007 to tell us how other small presses have reorganized in the age of Amazon to help shape literature now.

Appendix A

The statistical model used in this paper is one commonly used by Ted Underwood and others in recent literary scholarship.106

The model is a logistic regression on word frequencies, optimized to predict whether a novel was published by a nonprofit or conglomerate firm.107 To ensure the model's generality, it was regularized using an L2-penalty (C = 0.001) and a restricted vocabulary (5000 most frequent words); optimal values for regularization were selected by five-fold cross validation. The model was coded in Python using the scikit-learn package and implemented in a data capsule made available by the HathiTrust Research Center.108

Because the accuracy of our model was relatively low (66% f1-score), we took additional steps to ensure the validity of our findings. The statistical significance of the model's accuracy was determined by bootstrap (p < 0.05). Since novels published by conglomerates greatly outnumber those by nonprofits, the classes were balanced by downsampling. On average, there were about 140 novels in each category at training time.

The full code and findings are available at https://github.com/sinykin/nonprofit.

Dan Sinykin is Assistant Professor of English at Emory University. He is the author of American Literature and the Long Downturn: Neoliberal Apocalypse (Oxford University Press, 2020) and, forthcoming with Columbia University Press, The Conglomerate Era. He is the editor of Contemporaries at Post45.

Edwin Roland is a doctoral student in English at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His areas of research include American Literature and New Media. Previously, he was the Coordinator for Digital Literary Study with the Digital Humanities at Berkeley initiative. He holds an MA in the Humanities from the University of Chicago.

References

- George Hutchinson, Facing the Abyss (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), 66. [⤒]

- Scott Walker, "Preface," The Graywolf Silver Anthology (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 1999), xiii.[⤒]

- Jones left the magazine in 1963.[⤒]

- Claire Kirch, "Graywolf Press Celebrates Success," Publishers Weekly 251, no. 13 (2004). [⤒]

- Thomas Whiteside, The Blockbuster Complex (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1981). [⤒]

- John F. Baker and Calvin Reid, "Pantheon Echoes at NBCC Ceremony," Publishers Weekly, 237, no. 12 (1990): 13. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Robert D. McFadden, André Schiffrin, Publishing Force and a Founder of New Press, Is Dead at 78," New York Times, December 2, 2013, A31. [⤒]

- Edwin McDowell, "The Media Business; 40 at Random House Critical of Pantheon," New York Times, March 13, 1990, D23. [⤒]

- Robin Desser to Scott Walker, March 13, 1990," box 4 Graywolf Press Records, Mss095, Upper Midwest Literary Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Loren Glass, Counterculture Colophon (Redwood City: Stanford University Press), 204. [⤒]

- Ibid, 213. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Hutchinson, Facing the Abyss, 67-68. [⤒]

- Glass, Counterculture Colophon, 208. [⤒]

- Gayle Feldman, Chandler B. Grannis, and Daisy Maryles, "AAUP 1990," Publishers Weekly 237, no. 31 (1990): 18. [⤒]

- John Mutter and Maureen O'Brien, "ABA 1991," Publishers Weekly 238, no. 28 (1991): 19. [⤒]

- Lila Wallace Reader's Digest Fund Proposal, box 3, Graywolf Press Records, Mss095, Upper Midwest Literary Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- "Goals and Priorities, 1991-1992," box 3, Graywolf Press Records, Mss095, Upper Midwest Literary Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- 8 August 1991 Memo, box 3, Graywolf Press Records, Mss095, Upper Midwest Literary Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. [⤒]

- Lila Wallace Reader's Digest Fund Proposal, Graywolf Press Records. [⤒]

- Sherry Kempf, "Funding and Publishing: My Experiences with Graywolf Press," box 5, Graywolf Press Records, Mss095, Upper Midwest Literary Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Allan Kornblum, Memos/Notes box 5, Toothpaste/Coffee House Press Records, The University of Iowa Libraries. [⤒]

- Grants, box 4, Toothpaste/Coffee House Press Records, The University of Iowa Libraries. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- National Endowment for the Arts: A History, 1965-2008, ed. Mark Bauerlein with Ellen Grantham (Washington: National Endowment for the Arts, 2008): 18. [⤒]

- Ralph Ellison, "Introduction," Buying Time: An Anthology Celebrating 20 Years of the Literature Program of the National Endowment for the Arts (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press), xix. [⤒]

- Ibid, xx. [⤒]

- Ibid, xxiii. [⤒]

- Ibid, xxiv. [⤒]

- Mark McGurl, The Program Era (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), 32. [⤒]

- National Endowment, 185. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- "The Emergence of Literary Philanthropy," Publishers Weekly 244, no. 31 (1997): 44. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Fraser Carpenter Audit, box 2, Graywolf Press Records, Mss095, Upper Midwest Literary Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. [⤒]

- Kathleen Norris, "Profile of Coffee House Press," Poets & Writers (November/December 1992). [⤒]

- "Emergence," 44. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Joseph Barbato, "The Rise and Fall of the Small Press," Publishers Weekly 244, no. 31 (1997): 39. [⤒]

- Frank Conroy, letter of recommendation for Graywolf Press, box 3, Graywolf Press Records, Mss095, Upper Midwest Literary Archives. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- "Multi-Year Plan for Graywolf Press, 1984 through 1986," box 1, Graywolf Press Records, Mss095, Upper Midwest Literary Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. [⤒]

- Scott Walker to James Laughlin, box 4, Graywolf Press Records, Mss095, Upper Midwest Literary Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. [⤒]

- Fiona McCrae, "Letter to Graywolf Community," box 4, Graywolf Press Records (Mss095), Upper Midwest Literary Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. [⤒]

- For more on the whiteness of publishing, see Claire Grossman, Juliana Spahr, and Stephanie Young, "Literature's Vexed Democratization," American Literary History (forthcoming); Laura McGrath, "Comping White," Los Angeles Review of Books, January 21, 2019; Richard Jean So, Hoyt Long, and Yuancheng Zhu, "Race, Writing, and Computation: Racial Difference and the US Novel, 1880-2000," Cultural Analytics, January 11, 2019; Richard Jean So and Edwin Roland, "Race and Distant Reading," PMLA 135, no. 1 (January 2020): 59-73. [⤒]

- Derek Attridge, The Singularity of Literature (New York: Routledge, 2004). [⤒]

- Hathi's holdings are selective, containing those novels acquired by university libraries. We are working with Hathi to assess the histories of transmission that led to its holdings and, following protocols advanced by Katherine Bode, our findings are incomplete until we understand how the corporas' omissions shape our results. See Katherine Bode, A World of Fiction (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2018). [⤒]

- Ted Underwood, Distant Horizons (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), 25. [⤒]

- Andrew Piper, Enumerations (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 99-100. [⤒]

- In The Studios after the Studios and Hollywood Math and Aftermath, J. D. Connor writes about corporate self-allegorizing in film, as does Jerome Christensen in a series of essays, including "The Time Warner Conspiracy: JFK, Batman, and the Manager Theory of Hollywood Film," Critical Inquiry 28, no. 3 (Spring 2002): 591-617. Also see Sarah Brouillette, Literature and the Creative Economy (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2014) and Michael Szalay, "The Incorporation Artist" Los Angeles Review of Books, July 10, 2012. In Making Literature Now, Amy Hungerford illuminates the quotidian efforts of the many minds whose labor is required for any novel's publication. Amy Hungerford, Making Literature Now (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2016). [⤒]

- Percival Everett, Frenzy (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 1997), 4. [⤒]

- Ibid, 18. [⤒]

- Ibid, 24-25. [⤒]

- Ibid, 27. [⤒]

- Ibid, 49, 72. [⤒]

- Ibid, 124. [⤒]

- Ibid, 157. [⤒]

- Ibid, 2, 97, 110, 148, 154. [⤒]

- Ibid, 50. [⤒]

- Ibid, 118. [⤒]

- Ibid, 163. [⤒]

- Fiona McCrae, "Frenzy," Callaloo 28, no. 2 (2005): 329. [⤒]

- Percival Everett, Erasure (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2011), 4. [⤒]

- Ibid, 48. [⤒]

- Ibid, 43. [⤒]

- Percival Everett to Fiona McCrae, 27 March 1997, box 5, Graywolf Press Records, Mss095, Upper Midwest Literary Archives, University of Minnesota Libraries. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Rone Shavers, "Percival Everett," Conversations with Percival Everett (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2013), 49. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Everett to Fiona, Graywolf Press Records. [⤒]

- Robert Birnbaum, "Author Interview: Percival Everett," Identity Theory (6 May 2003). [⤒]