New Filmic Geographies

James Baldwin is everywhere in the twenty-first century: circulating on Twitter and Instagram; ventriloquized by public intellectuals such as Ta-Nehisi Coates, Eddie Glaude, and Jesmyn Ward; and adapted in cinema. The dominant social media image of Baldwin is the one we find in the most viewed Baldwin video on YouTube — that of his Cambridge address from February 1965, where he debated William F. Buckley to instant acclaim from the audience. This is the Baldwin who continues to energize audiences: lucid and eloquent, combative yet respectful, committed to radical change.1 This iconic Baldwin is easily transportable from the civil rights movement to the anti-racist struggles of the present. Cinema has been one vehicle for such transport. Two recent high-profile Baldwin adaptations — Barry Jenkins's If Beale Street Could Talk and Raoul Peck's I Am Not Your Negro — have been catalysts in Baldwin's repurposing for today.

But these two films engage less with the fiery, Instagrammable Baldwin than with a form of stylistic and political lateness in his work. In cultural theory, lateness is not automatically identified with loss and diminishment; in Baldwin scholarship specifically, a traditional declension narrative has made way for a renewed appreciation of Baldwin's works after the failure of the civil rights struggle—as works having their own stylistic strengths and political vision.2 That vision itself is marked by lateness: Baldwin's mature awareness that white concessions will always come too late and that what remains is to witness rather than prevent the apocalyptic undoing of America.3

Late Baldwin is liberated from the illusion of American exceptionalism and bears a renewed awareness of the transnational entanglements of African American suffering — with Africa, with capitalist globalization, with the Algerians he met in Paris and from whom the early Baldwin still felt himself separated by "a gulf of three hundred years."4 In Begin Again, his recent reappraisal of Baldwin's undiminished political relevance, Eddie S. Glaude Jr. champions Baldwin's later work, insisting "we cannot cordon off his rage." To him, Baldwin "saw something in those years leading up to the election of Ronald Reagan,"5 something that he sought to prepare us to endure, albeit in a more disillusioned and resigned fashion than in his early work. At a recent online Heidelberg lecture, Glaude formulated it as follows: "To stay with the later Baldwin is to stay close to the fire. Baldwinis not so much concerned with the white gaze in the later work. And it's a really uncomfortable space for certain people to be in."

Baldwin's signature lateness — his combination of disillusionment with the US and transnational consciousness — infuses the two films; they connect his lateness to the exploration of new filmic geographies, and this means that, in spite of the films' decidedly American subject matter, they participate in the temporal and spatial complexities of today's world that, as this cluster argues, characterizes contemporary transnational cinema more generally. Baldwin's Cambridge address is a key resource for Peck's film (Fig 1 & 2), and the occasion for one of its most quietly spectacular visual twists. At the film's one hour-mark, as Baldwin receives a standing ovation and returns to his seat, the footage suddenly becomes colorized (Fig 3 & 4). The transition offers no moment of enchantment, no triumph, but a shift toward doubt: Baldwin has just won over the (overwhelmingly white) audience, yet looks about skeptically, appearing isolated.

Fig. 1-4: Baldwin finishes his Cambridge address, February 1965.

Baldwin was, at this moment, about to tumble into lateness. Three days after the debate, Malcolm X was killed. Six months later the Voting Rights Act would be signed into law. The civil rights movement was ending, Black Power rising. Baldwin was uncertain, in the film's clip, because he was changing his mind — about many things. Not least, he would more and more address Black audiences in his work. It is late Baldwin who is the animating force of Peck's film, with the book-length 1972 essay No Name in the Street serving as a main source text for the film's voice-over. At first sight, it might be tempting to oppose I Am Not Your Negro to Jenkins's Beale Street: transnational arthouse cinema vs. inoffensive Hollywood melodrama (a marked shift for Jenkins from the indie-vibes of Moonlight); unreconciled activism vs. indulgent seventies Harlem nostalgia; collage vs. extreme close-ups (reminiscent of Jonathan Demme's Beloved — Fig 5 & 6). But what connects the two is that Jenkins's film is itself inspired by a later Baldwin — by a novel that, at the time of its publication in 1974, for most contemporary readers proved Baldwin-the-novelist's waning powers.6

In Baldwin's twenty-first-century movie career, then, he is not an eternally young and relentlessly energetic fighter; he is a more temporally complex figure who speaks to the present, even if that address is less direct than Baldwin's posthumous career on social media platforms suggests. And he does so not in spite of, but because of his waning faith in the possibility of revolution. Both Beale Street and No Name reflect what Eddie S. Glaude Jr. calls Baldwin's "experience of the after times," his experience of "the reality of loss" after the murder of Martin Luther King and the quickly faded promises of the end of Jim Crow.7 Importantly, for Glaude, that experience found its form through Baldwin's exile in Instanbul — an "elsewhere" that "allowed him the critical distance from the deadly dynamics of American life."8 Douglas Field, also, argues that Baldwin's exile eroded the American exceptionalism of his early essays, as "his later work, in particular, shows that he was keenly attuned to North America's role in a global context, both militarily and culturally."9 Baldwin's cinematic afterlives reveal historical and geographic discontinuities. Crucially, for both Jenkins and Peck, distension across time is connected to their and their subject's transnational experience. New filmic temporalities shade into new filmic geographies: Baldwin's own complicated expatriate status (spread across Turkey, Paris, the South of France, and New York) inspires the transnational experiences of Jenkins and Peck; their films, for all their surface sleekness, register Baldwin's inspiration while insisting that his seductive image cannot simply be recycled for the present. Underneath the smooth visual surface of Beale Street and the soothing voice-over of I Am Not Your Negro, elements of a more accidented, recalcitrant, and uneven transnationalism remain apprehensible.

***

The stylistic lateness of I Am Not Your Negro is nowhere more apparent than in its voice-over. Peck's collage of interview and speech footage, of popular culture snippets from Baldwin's time and explicit analogies to our own, is strung together by the flow of Samuel L. Jackson voice-over, ventriloquizing a weary and battered Baldwin looking back on the lives and deaths of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King. Peck's project was inspired by the unfinished manuscript of Remember This House, a memoir detailing Baldwin's personal recollections of the three civil rights icons. Still, Jackson's voice-over does not draw exclusively from this manuscript, but is the result of an extensive cut-and-paste process that mixes phrases (sometimes mid-sentence) and paragraphs from a wide variety of Baldwin texts. Dagmawi Woubshet has argued that one stylistic feature of Baldwin's late style was its "interior look at intramural black life," deploying a gaze not confined by the white-black dialectic that dominates early Baldwin's work.10 The way Jackson's voice-over (in a tenor that does not erase its difference from Baldwin's own diction in the many fragments the film collects) contains the diversity of the film's source material in a recognizably Black voice achieves something similar for I Am Not Your Negro's stylistic lateness: Jackson's voice packages the interracial tensions the film documents as a decidedly Black engagement; the voice-over positions the audience as overhearing a ruminative Black voice, rather than inviting it to engage in debate. The film's voice-over, like late Baldwin, knows the time for debate is over.

I Am Not Your Negro undeniably foregrounds the resonances between Baldwin's and today's America; by distilling a seemingly coherent voice-over from various Baldwin texts, it also hints at the essential unity of Baldwin's different incarnations. Still, the illusion of a steadfast continuity of thought, style, and reception are shadowed by the film's post-revolutionary (after the death of Evers, Malcolm, and King) and posthumous (Jackson ventriloquizing Baldwin) perspective. And temporal discontinuity shades into spatial discontinuity, lateness into exile as the film shuttles between Hollywood and Harlem and between the Deep South and New England auditoriums.

As Peck emphasizes, he himself was born in Haiti and lived from an early age on alternately in Congo, France, Germany, and the United States. In the introduction to I Am Not Your Negro's published screenplay, Peck reminisces on his early readings of Baldwin at the age of fifteen. Young Raoul considered Baldwin one of the few authors he could call "his own"; he cites Baldwin's power to help him "connect the story of a liberated nation, Haiti, and the story of the modern United States of America and its own painful and bloody legacy of slavery."11

I Am Not Your Negro is a thoroughly transnational film. Peck's production team consisted primarily of French collaborators. Among them, editor Alexandra Strauss echoes similar sentiments when asked how she approached the mindset of her subject: "When I think about French history and politics in France today regarding foreigners, and how French people act now with all the migration, a lot of things that [Baldwin wrote about] also spoke to me.... Maybe the distance helps."12 The film came about as a co-production between the United States, Switzerland, France, and Belgium. Its commercial circulation in all these countries vastly exceeded any reasonable expectations for a documentary film. In Belgium (where we live), the film was streamed for free on several online platforms, including public broadcasting, in honor of "Blackout Tuesday," a worldwide protest against racism and police brutality. That Blackout Tuesday originated in the United States in response to the killings of George Floyd makes it tempting to read this transfer as an American imposition — even in the domain of countercultural protest — and Baldwin as a posthumous cheerleader of such impositions. Still, the transnational impetus that the film reflects and transmits delivers a more interesting filmic geography: one in which different diegetic and nondiegetic contexts refract one another without surrendering their specificity, a network in which no single node remains uninflected by others.

***

Barry Jenkins wrote his script for Beale Street back-to-back with that of Moonlight while he was on a trip through Europe in the summer of 2013. He has noted how "as an artist the air around you kind of affects how you approach your own work. And this was one of those periods in my life where there was just no air around me. It was just me and the work"13 — an experience he links to Baldwin's cosmopolitanism. For Jenkins, Baldwin's role as an observer of Black society and culture was aided by his self-imposed exile: "He felt like, especially at the age of 18, 19, I think, that living in America, even in New York, as a Black American was suffocating him, because he felt these micro-aggressions, pressures, these dangers to be himself. So he had to get outside of the country to really look back and reflect on who he was and his take on Black America."14 The Baldwin quotation that opens the film (Fig 7)marks that broader outlook: first defining Beale Street as the place "[e]very black person born in America was born" (a zooming gesture that informs the film's attention to period detail and to the evocation of Black American life), it notes that "it is left to the reader to discern a meaning" in the drumming sound of Beale Street.

Although the vast majority of Beale Street takes place in New York City, the film clearly accentuates that each geographical coordinate (Harlem, New York as a whole, but also, as we will see, Paris and Puerto Rico) is shaped by transnational dynamics (rather than a self-contained unit that can simply be transported abroad — like a James Baldwin meme). Harlem is home to the characters' origins, yet they are in constant motion, searching for spiritual freedom and financial opportunities elsewhere in the city. Rather than providing actual shelter, these locations force the protagonists to reflect on their status, their Blackness in an alien white world.

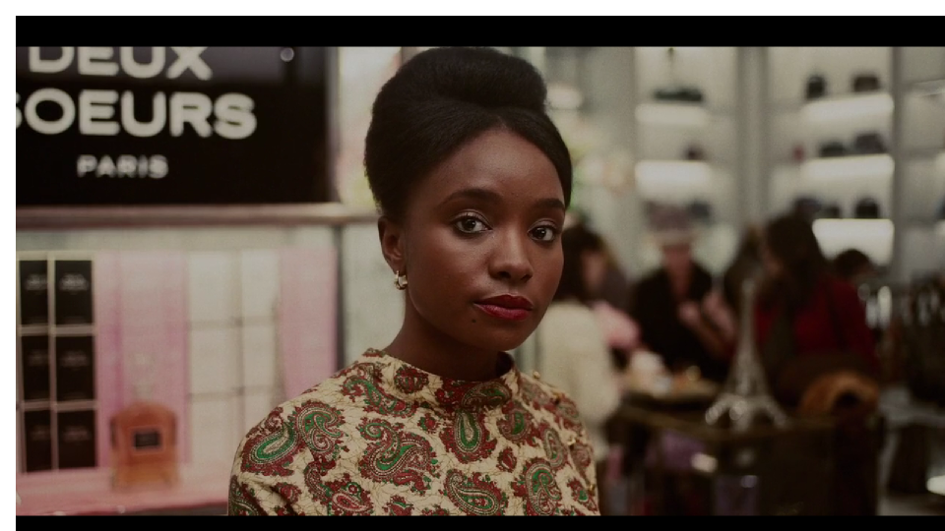

Halfway through the film (Fig 8), Tish, the female lead, has been hired for a counter job in the Bergdorf Goodman on Fifth Avenue; "the store thought that it was very progressive to give this job to a colored girl," we hear. In voice-over she narrates her negative experiences with white co-workers and customers, in contrast with the sympathetic gestures from the occasional Black shopper. "Perhaps for a black cat, I look like a helpless baby sister," Tish concludes. Jenkins's montage keeps framing the perfume brand Tish is promoting: Deux Soeurs — Paris (Fig 9 & 10). It is a fictional brand, and its connotations are not hard to intimate. The name echoes — or subverts? — Les Deux Magots, the legendary Parisian café where Baldwin would meet his fellow Black expatriates Richard Wright and Chester Himes. Yet, in contrast to Baldwin and Wright's well-publicized feud, the perfume contains the promise of enduring connection: even away from home (the luxurious store a stand-in for the Paris of her dreams), Tish does not stand alone.

Adding this perfume to his novelistic source text, Jenkins is here intimating a mode of Black connection across the Atlantic that, as Douglas Field explains, was simply unavailable to the younger Baldwin. Only in his late work, Field notes, is Baldwin "increasingly attuned to the internationalism of the Black experience."15 A similar entanglement transpires in the novel's and the film's engagement with Puerto Rico. Tish's lover Fonny is wrongfully framed for the rape of the Puerto Rican Victoria, who has fled to her hometown before Fonny's trial could commence. In the novel, when Tish's mother Sharon travels to Puerto Rico to seek out Victoria, her first impression at the San Juan airport is "that everyone appears to be related to each other. This is not because of the way they look, nor is it a matter of language: it is because of the way they relate to each other."16 Jenkins's adaptation adds an awareness of unevenness to this entanglement. This observation is left out, but the original draft of the screenplay includes a short exchange between Sharon and an airline staffer with the description that "it must be noted: for a black woman raised in the Jim Crow South, this is one of the few moments in Sharon's life she can be said to emit privilege."

In both the novel and the film Sharon repeatedly addresses Victoria as "daughter," and she futilely asks her why she came back to Puerto Rico after being raped. In the film, Victoria does answer ("If it happened to you...what would you do?"), but the original screenplay sticks much closer to Baldwin's text:17 "Victoria rises and walks to the window. Sharon follows, the two of them staring out at the sea together. A prolonged silence, a fleeting truce inspired by this view." Even in their slightly altered form, the finalized scenes in Puerto Rico echo and update the late Baldwin's concern with the parallels and dynamics between Harlem and Puerto Rico. Much like Harlem is entangled with downtown NYC, Puerto Rico is entangled with the country of which it is an unincorporated territory.

The subdued transnationalism of Jenkins's film, then, is emphatically a replay of the late Baldwin — a lateness that is stylistically rendered by the film's overt 1970s nostalgia; rather than transposing Moonlight's at times gritty realism to the streets of Harlem, Jenkins and cinematographer James Laxton submerge their images in sumptuous and warm colors, while Moonlight's handheld cameras have been traded for majestic, steady, and wide camera movements.18 There is a dreamlike quality to the cinematography, confidently aestheticizing the beauty of the Black lives on display. Beale Street is powered by Jenkins's own temporary exile from the USA — an exile that echoes Baldwin's belief in the need for spatial distance. Not for nothing does From Another Place, Sedat Pakay's 1970 short film chronicling Baldwin's stay in Istanbul, take its title from Baldwin's statement that "[t]he American power follows one everywhere . . . in a way, being out, even temporarily, and with a perfect awareness that one is not really far out of the United States...one sees it better from a distance . . . from another place."

***

Cut back to I Am Not Your Negro's colorized coda of the Cambridge address, where we have seen Baldwin's unease amid the applause. The scene is followed by 1963 footage from the Hollywood Roundtable, a debate between artists and filmmakers over civil rights. Harry Belafonte warns David Schoeburn about the responsibilities that await the white community after the civil rights era. Next, the camera lingers on anonymous streets by nightfall, over which Samuel L. Jackson laments: "Simplicity is taken to be a great American virtue along with sincerity." (Fig 11 & 12)

In the film the line functions as a bitter counterpoint for what is to follow: an "apology sequence," sampling a series of excuses that reliably arrive too late, after historical damage was done — from Richard Nixon up to Ferguson police chief Thomas Jackson. White responsibility, it seems, always arrives too late, and that awareness informs Baldwin's own late work — a lateness that, as we have argued, consists in a radical disbelief that responsibility will ever come in time. Taking inspiration from the temporal complexities in Baldwin's life and work, while at the same time channeling their own transnational experiences, Jenkins and Peck convey filmic geographies that cannot be reduced to the condensed images and singular visions and emotions that Baldwin's social media persona is often made to render. This, we submit, is one way to stay close to the fire.

Remo Verdickt is a doctoral researcher working on the posthumous career of James Baldwin at the University of Leuven.

Pieter Vermeulen (@pieterv23) is an associate professor of American and comparative literature at the University of Leuven. He is the author of Romanticism after the Holocaust, Literature and the End of the Novel, and Literature and the Anthropocene.

References

- Melanie Walsh's website http://tweetsofanativeson.com/ provides the numbers on Baldwin's afterlife on Youtube. It also provides much other evidence for the dominance on the years between 1960 and 1966 in the social media life of Baldwin. All ten of the most retweeted tweets in the period Walsh investigates contain quotes and images from these years; the six most quoted texts all date from this period (the most quoted one is a Huey Newton quotation from 1968 that renders a 1961 source text). Walsh's data on library borrowings (where Baldwin's works from the 50's and early 60's prove most popular) and YouTube viewings corroborate the overwhelming popularity of a younger Baldwin. [⤒]

- See especially Dagmawi Woubshet, "James Baldwin's Late Encounters with Africa," Nka 42-43 (2018), 222-232. [⤒]

- For the apocalyptic Baldwin, see Dan Sinykin, American Literature and the Long Downturn (Oxford : Oxford University Press, 2020), 23-46. [⤒]

- James Baldwin, "Encounter on the Seine: Black Meets Brown" in Collected Essays, edited by Toni Morrison (New York: Library of America, 1998), 89.[⤒]

- Glaude, Begin Again, xxviii.[⤒]

- Only Joyce Carol Oates was an outspoken fan; Toni Morrison, in private correspondence, regretted not being able to sign the book with Random House and expressed her wish to "become an If Beale Street Could Talk groupie." See Conseula Francis, The Critical Reception of James Baldwin, 1963-2010 (Rochester: Camden House, 2014), 45, 116-117; Douglas Field, All Those Strangers: The Art and Lives of James Baldwin (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 152.[⤒]

- Eddie S. Glaude Jr., Begin Again: James Baldwin's America and its Urgent Lessons for Our Own (New York: Crown, 2020), 119-120.[⤒]

- Glaude, Begin Again,129. See also Magdalena J. Zaborowska, James Baldwin's Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 5, 28.[⤒]

- Field, All Those Strangers, 118.[⤒]

- Woubshet, "Late Encounters," 229-230. [⤒]

- Baldwin and Peck, I Am Not Your Negro,ix-x. [⤒]

- Liz Nord, "Oscar-Nominated 'I Am Not Your Negro': How Editor Alexandra Strauss Cut an 'Impossible' Film," No Film School, February 3, 2017.[⤒]

- Jake Coyle, "Fall Preview: Barry Jenkins on Adapting James Baldwin," AP News, August 30, 2019.[⤒]

- TIFF Talks, "If Beale Street Could Talk Director Q&A," YouTube, September 12, 2018.[⤒]

- Field, All Those Strangers, 116.[⤒]

- James Baldwin, Later Novels, ed. Darryl Pinckney (New York: Library of America, 2015), 471.[⤒]

- Ibid., 488.[⤒]

- Jenkins has stated the film's color palette nods to the work of Douglas Sirk and Vincente Minnelli partly in order to counterbalance its "well-tread story of African-American pain and imprisonment." See Chris O'Falt, "If James Baldwin Made Films: How DP James Laxton Translated the Bold Imagery of 'Beale Street'," Indiewire, January 9, 2019.[⤒]