New Filmic Geographies

That we think of national cinemas as a natural category has little to do with any quality inherent in a given filmic text. 1 In the heady early days of cinema, from cinema's introduction in the late nineteenth century to the early teens, a global moment for film, assigning films national identity had less to do with the narratives being told than with tussles over market share. As Richard Abel has shown, American films became American through discourse that contrasted them with the French films that American producers wanted to excise from the US market.2 By now, the habit of organizing global cinema by nation — Italian, Chinese, Argentine — has become entrenched and informs the organization of academic study as well as the institutions, such as film festivals and awards shows, that work to assign cultural value to films. For the purposes of this short inquiry, I take up William Higbee and Song Hwee Lim's 2010 call to "examine the interface between global and local, national and transnational" with the goal of pushing against the entrenched habit of privileging the nation so we understand how cinema moved historically across a variety of geographical scales, as it continues to do today.3

I focus on the trade press and its advertising and illustrations, specifically images of globes, maps, and iconographic representations of places that appeared from roughly 1907 to 1945. The trade press, which emerged in the late aughts, spoke to exhibitors, producers, and companies that produced equipment, introducing available films through advertisements and reviews, and editorializing about the state of the industry, taking on issues such a censorship, tension between distributors and exhibitors, and the state of the market for film at home and abroad. The visual landscape of the trade press, especially after the mid-teens, privileged photographs from specific films or of film stars, film company executives, and even equipment or studios. Maps are less frequent but are worth examining for what they tell us about the spatial imagination of the business of cinema at the time. They visualize hoped-for audiences or markets, document circuits, and establish brand identities. They allow us to see a multi-scalar geography of cinema in which the transnational, national, regional, and local co-exist in productive tension. My evidence is selective, even eclectic, due to the contingencies of our current situation. It is drawn primarily from the trade press in the United States with additional material from France and Argentina. But it allows us to begin to think through and with the map as a cinematic interface.

The best place to begin is with the original Universal Film Manufacturing Company trademark. Established in 1912 out of an alliance between a number of independent film producers not beholden to the Motion Picture Patents Company Trust, Universal aimed to be an innovator in the film production sector. It opened the first extended studio complex on a large piece of land in San Fernando and in addition to producing popular serials was an early adopter of the feature film format when other firms were still making one- and two-reel films. Upon its founding the company took up the image of a globe circled by rings as the visual analog to its name. This image conveyed, as Mark Garrett Cooper observes, "velocity as well as an ability to fix or bind."4 While the Universal trademark is almost schematic — the outline of a globe filled with fuzzy landmass shapes rendered in stippling — it suggests that the company was committed to "cover[ing] the largest territory possible."5 In the case of Universal, these aims seemed more likely to be realized by 1916 when the company had opened offices in countries from Europe to East Asia.

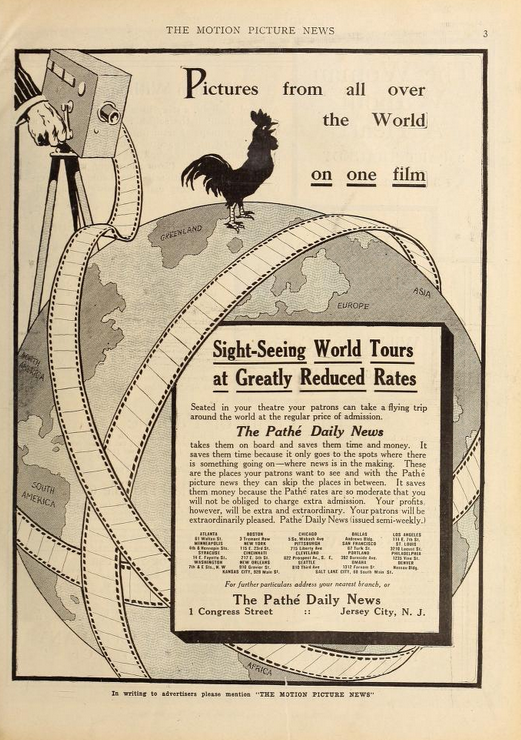

But Universal was not the only company to take up the globe as a symbol of its aspirations. In 1910, L'Aubert, a French distributor of Italian, Danish, and British films, adopted an eagle astride a globe wrapped in film as its trademark and Nordisk, the Danish producer, imagined its company's reach as a polar bear astride a globe. In 1914, the Sawyer film mart likewise imagined its decidedly domestic circuit of offices via film-wrapped globes. And that same year, the Pathé Daily News promoted its "world tours" in the form of a newsreel with the company's trademark rooster perched atop a globe circled by film emerging from a Pathé camera.

In each of these cases, the globe suggests hopes for commercial prospects. These hopes were not unfounded in a world increasingly connected by modern technologies, including film cameras themselves, that allowed the rapid flow of media across borders.

World War I was a boon for US-based producers who took the opportunity to aggressively expand into overseas markets. By the 1920s, those producers now organized as Hollywood dominated global screens, a state of affairs that lasted through the 1930s, even as the introduction of sound technology encouraged autochthonous film production. World War II foreclosed markets in parts of Europe and Japan, so Hollywood turned to Latin America and cultivated markets there even more insistently.

This motif of global aspiration was not limited to producers and distributors. When the trade journal, The Moving Picture World, appeared in 1907, it featured a globe balanced on two reels of film on its masthead. While that image would give way to an image of a proscenium arch under which photographs of stars could be rotated in and out for each issue, it does suggest the ambitions of the publication. In this case, the initial goal was not precisely one of global domination, but of comprehensiveness: the journal's content covered not only films and the people who made them but also the finer points of exhibition, projection, and marketing. It is telling that even here the allure of the globe as motif prevailed, as the prospective readership was primarily limited to the domestic, English-speaking US market. This sort of global vision related less to fantasies of sales and markets than to breadth of service. But it suggests that as US-based film producers began to assert themselves as a dominant force in the highly connected world of early narrative film, the appeal to the global as representative of comprehensiveness might have seemed easy, even natural.

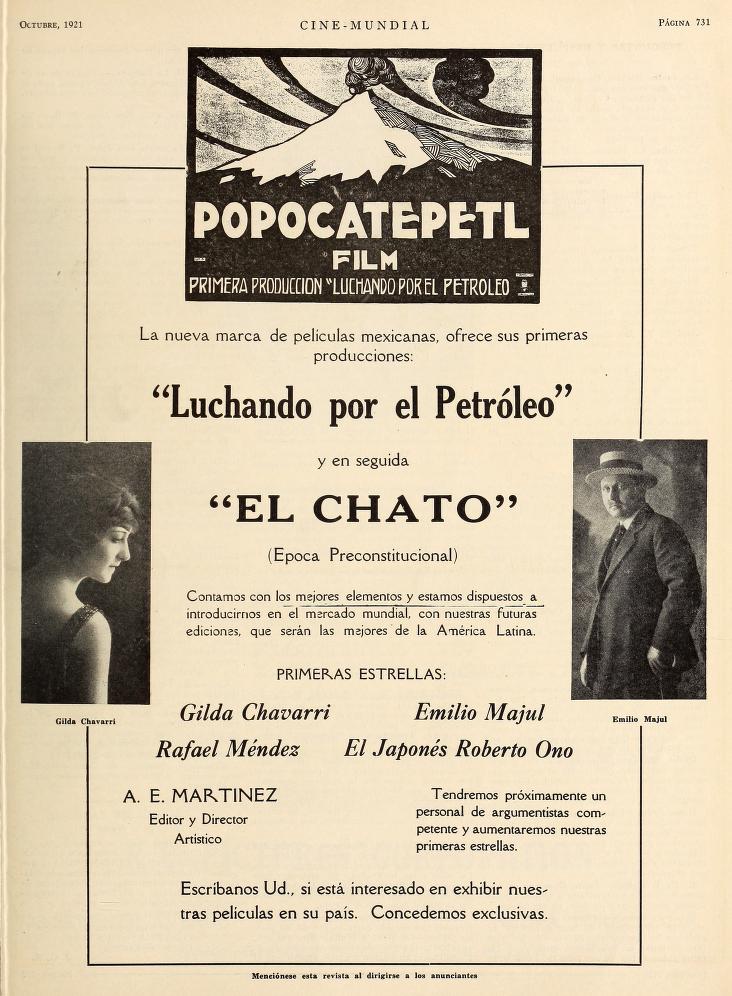

At the same time, film companies traded in local geographies when producing their brand identities. To offer one example from the early teens, Vesuvio Films in Naples, Italy used a drawing of Mt. Vesuvius, the volcano, as its logo in advertisements taken out in the French trade journal Cine-Journal. In the 1920s the Mexican film company Popocatepetl Film featured an image of its eponymous volcano in a style that suggested a modern woodcut print, connecting the company's products with Mexican modern art. These two strategies — the global and the hyperlocal —coexisted. They visualized market aspirations and strategies for product differentiation in a field dominated by larger production firms with global reach, which by the 1920s were largely Hollywood firms such as Paramount Artcraft, Universal, and Goldwyn.

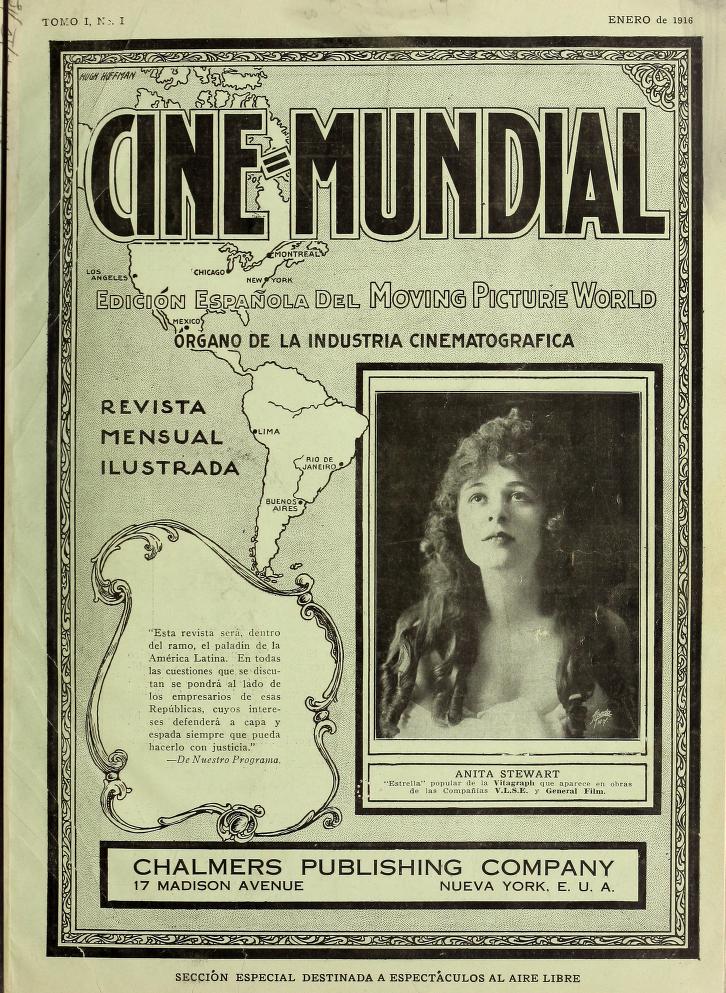

When the US film industry set its sights on foreign markets in the late teens, maps were important visual tools. For example, in 1916, the first year of its publication, Cine Mundial, the Spanish-language version of Moving Picture World — although to call it a version is to underplay its originality and independence — featured a map on its inside front cover.6 The map depicted the location of its intended readership, namely the entire western hemisphere save Canada, which was pictured but set apart by the only border line on the map.7 While the globe motif explored above presented continents as unmarked landmasses, on this map key cities are called out: Montreal, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Mexico, Lima, Buenos Aires, and — despite its not being in a Spanish-speaking country — Rio de Janeiro. In this way, this map imagines the film business as an endeavor that connects urban centers.

Advertisers in the pages of Cine Mundial, such as First National Exhibitors Circuit and the Novelty Slide Company, did not hesitate to invoke the hemisphere in conjuring the market for their wares. This new geography of urban centers became significant. Like the globe imagery in the first issues of The Moving Picture World, Cine Mundial's map disappears, again replaced by a graphic allusion to the theater that became the container for photographs of film stars and images from specific films. But its geography was dispersed into the pages of the publication. Cine Mundial adopted a structure in which, after general features and columns, activities and news were organized by country or city in reports from dedicated correspondents that were accompanied by photographs. Each issue featured reports from major urban centers across the continent: Mexico City, Buenos Aires, Havana, Lima. These reports were about the circulation of the products of US-based film companies, but they were also about the other things: local film production, theater, leisure culture, and even politics. These monthly reports replaced the original map, but in textual and photographic form. The imagined readership projected by the initial hemispheric map with urban nodes became realized in the structure of the journal itself.

Regional distribution, which also appeared in Cine Mundial, fostered its own cartography. For example, in 1918, the Empresa de Teatros y Cinemas Ltda. in Lima, Peru described its trade in "the best American brands" and "the best European films" with a map punctuated by arrows pointing to cities where its wares were being shown, which ranged from Puntas Arenas on the southern tip of the continent to Quito, Ecuador. This map emphasized the company's role as a mediator between the US and Europe and the western coast of South America, but visually it privileged regional circuits. To take another example, Di Domenico Hnos. y Cía., based in Bogota, Colombia represented its own regional market with a map depicting Central America, Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador against a horizon as if this part of the world had been sliced from a globe. This technique gave dimension to a planar representation, allowing associations between their business and an open, promising future.

We see in the pages of Cine Mundial strategies of geographic visualization that supported the publication's aim of promoting films made in the United States. But more surprisingly, we also see parallel strategies that visualized the formation of a market and audiences linked by cultural formations and regional trade circuits that exceeded and supplemented the circulation of US-produced films.

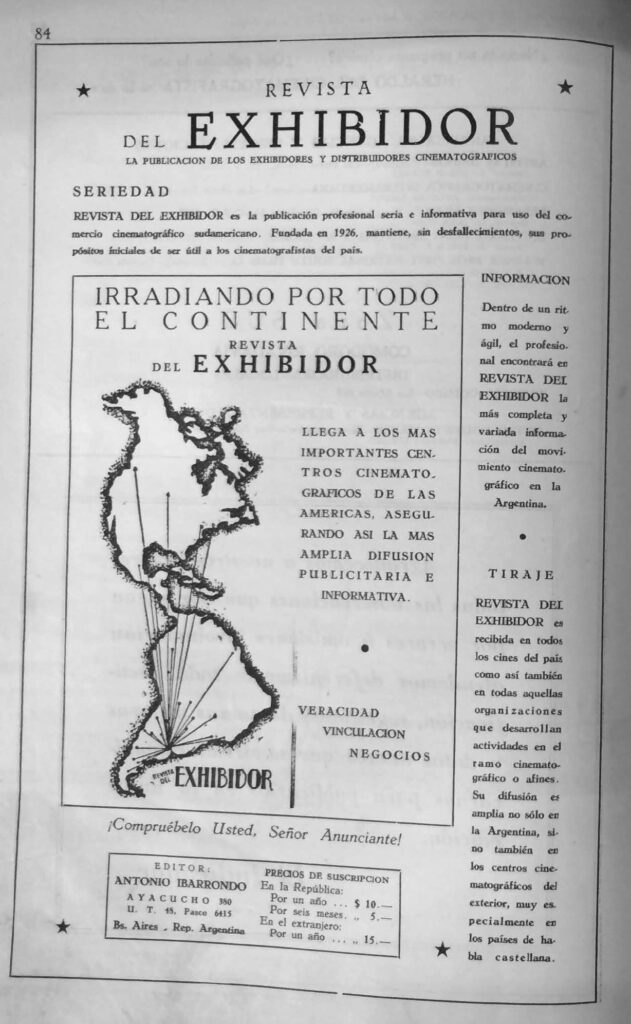

Geographic circuits of film were also influenced by technological developments in the industry. As is well documented, the coming of sound, while perhaps not upending the balance of power in the global film market, made it possible to imagine films flowing in new directions. Local film producers rushed to give audiences films that were not merely versions of US films in other languages but were culturally specific in appealing ways.8 While this might not have had a huge impact on more established film industries in Europe, it created significant opportunities for film industries in other parts of the word such as Latin America. To be fair, Latin American films, especially Mexican films, had already achieved limited circulation on the US side of the border in ethnic Mexican communities, but sound made it possible to imagine this circulation on a much broader scale.9 Take for example the case of Argentina. During the 1920s, Argentina had constituted one of the key Latin American markets for films produced in the United States.10 In the late 1930s and 1940s Argentine film studios began to make films that held increased appeal for domestic audiences.11 What is more, some of Argentina's productions, especially tango films, appealed to audiences in Latin America and Spain, challenging the dominance of US produced films.12 The possibilities of this new, albeit unequal flow of films across borders were once again visualized in advertisements in the trade press that made Argentina the center of circuits of distribution across the hemisphere.

In the late 1930s and 1940s Argentine trade press, globe imagery continued to be a recurring motif used by production companies and purveyors of ancillary goods as banal as floor wax. More interesting are maps that show the relationship between Argentina and the United States. These maps, created from the perspective of the south, unsettle any notion that the traffic in film was or could only be imagined as unidirectional. To offer one example, in an advertisement in the 1943 Indicador: guía manual del cinematografista, a yearly Argentine publication for the film industry, the company Establecimiento Filmadores Argentinos claimed to have "knocked down all the barriers in Latin America."13 The company represented this conquest via dropped pins on a map of the hemisphere, indicating where its product was being distributed and by whom. Those business partners included firms from Texas to Uruguay. Similarly, an advertisement for Revista del Exhibidor, an Argentine trade publication in the 1944 issue of the Indicador, made Buenos Aires the point from which information about films and film culture radiated across the continent.

But visualizations of the film business could also be hyperlocal during this period. In contrast to the iconographic approach to the local found in the early trade press, representations of the local now also used maps to suggest the spatial distribution of the film industry in specific locales. Take for example a map published in the trade magazine Imparcial Film in 1939. The image laid out Argentina's film studios over a street map of the capital Buenos Aires. This map suggests that the business of making films dominated the entire city — and even suburbs that were not depicted on the map. Similarly, in a 1945 issue of Revista de Exhibidores,multiple maps of the country's provinces were surrounded by lists of the cinemas in each province over a five-page spread that depicted the way that cinema going had permeated the country. Even more pointedly, an advertisement by a realtor in Revista de Exhibidores emphasized the business possibilities of a few blocks in the Vicente López neighborhood in Buenos Aires, where an existing cluster of film-related businesses made it a prime location for a studio or laboratory. A business that was, by its nature, transnational was also insistently regional and local.

These views from different perspectives and scales notwithstanding, maps could still be used in support of unequal power relations. An article about the business potential of Latin America for film producers and distributors published in 1939 in The Motion Picture Herald provided readers with a map that summarized the contents of a lengthy article.14 The map, under the heading "Opportunities below the Rio Grande," carefully delineated each country, identified major cities, and related key statistics — number of cinema seats, taxes, censorship — that might help readers gauge the business possibilities of any given country or city. The map visualizes reports prepared by the US Department of Commerce, which saw all foreign countries as potential markets for US goods, including but not limited to films. In a testament to the flexibility of maps, this same map was some months later reprinted in the Heraldo del cinematografista,which had translated its legend. The publication celebrated the fact that it had originally been published in "the prestigious New York magazine Motion Picture Herald" and "judged that it would be of great interest" to its readership. We can deduce that local film empresarios saw this information as potentially useful in promoting their own interests. In this way, visualizations of film infrastructure lent a form of agency to those working in the south, seizing a tool designed to advance a unidirectional US interest to their own advantage in promoting their own business interests as brokers of foreign or domestically produced films.

In the globes, maps, and iconography of the trade press before 1945, we do not see national cinemas but transnational exchanges at overlapping scales.15 Those scales, constantly in tension, ranged from local film business districts to expansive conceptions of Latin America, the hemisphere, and the world. Studying the map as a visualization of cinema's multiple interfaces allows us to uncover more complex stories about cinema's travels, rethink the shape and scope of concepts such as national cinema, and question received narratives about the direction of film traffic at any given moment.

Laura Isabel Serna is Associate Professor of History and Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Southern California. She is deeply interested in how things, like films, move across borders.

References

- Thank you to Nic Poppe for sharing his treasure trove of maps from the Argentine trade press.[⤒]

- Richard Abel, The Red Rooster Scare: Making Cinema American 1900-1909 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999). [⤒]

- William Higbee and Song Hwee Lim, "Concepts of Transnational Cinema: towards a Critical Transnationalism in Film Studies." Transnational Cinemas 1, no. 1 (2010): 7-21; 10.[⤒]

- Mark Garret Cooper, Universal Women: Filmmaking and Institutional Change in Early Hollywood (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 1.[⤒]

- Cooper, Universal Women, 1. [⤒]

- Cine Mundial was owned and published by Chalmers Publishing, but had a separate editorial staff. [⤒]

- To a certain degree this image contravenes the textual description of the publication's proposed readership, which included the western hemisphere and the Iberian Peninsula.[⤒]

- On this point see Lisa Jaarvinen, The Rise of Spanish-Language Filmmaking: Out from Hollywood's Shadow, 1929-1939 (Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2012), 160-164. [⤒]

- Rogelio Agrasanchez offers the most detailed account of this circulation in Mexican Movies in the United States: A History of the Films, Theaters, and Audiences 1920-1960 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2006). [⤒]

- Kristin Thompson, Exporting Entertainment: America in the World Film Market 1907-1934 (London: BFI Publishing, 1985), 79-80; 139. [⤒]

- Matthew Karush notes that Argentine audiences remained quite stratified by taste. Culture of Class: Radio and Cinema in the Making of a Divided Argentina 1920-1946 (Durham, NC: Duke University press, 2012), 71-84. [⤒]

- On this see Rielle Navitski, "The Tango on Broadway: Carlos Gardel's International Stardom and the Transition to Sound in Argentina," Cinema Journal 51, no. 1 (Fall 2011), 29. Nicolas Poppe has written about the film's Gardel made for Paramount at Joinville, France during the vogue for multi-lingual production. "Made in Joinville: Transnational Identitary Aesthetics in Carlos Gardel's Early Paramount Films," Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies 21, no. 4 (2012): 481-495. [⤒]

- Advertisement, Establecimiento Filmadores Argentinos, Indicador: guía manual del cinematografista, 1943, 31[⤒]

- "5,077 Theatres Serve 120 Million in 19 South American Countries." Motion Picture Herald, April [date], 1939. [⤒]

- The circulation documented (or aspired to) on these maps and their imagination of global, regional, and local markets nurtured affective connections amongst Latin American film publics who consumed both international and local films. Those geographies too existed in multiple scales that can be mapped and compared. The formation of this transnational audience is ably explored in Rielle Navitski and Nicolas Poppe, Cosmopolitan Film Cultures in Latin America 1896-1960 (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2017).[⤒]