Issue 7: Post45 x Journal of Cultural Analytics

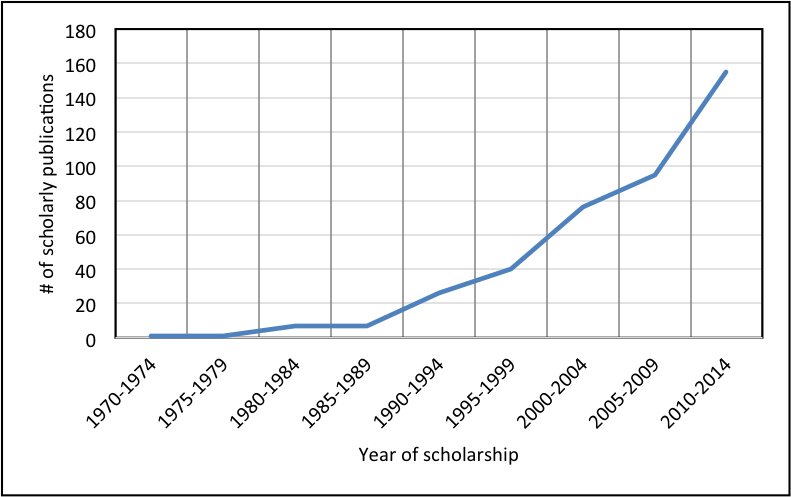

Asian American literature has grown dramatically in recent decades, reflecting a broader acceleration in contemporary cultural production.1 While no comprehensive bibliography of Asian American literary publications exists, we can look at the number of Asian American texts discussed in the field. From 2000-2016, the number of unique texts discussed in Asian American literary scholarship was nearly 600, with the majority (62%) published in the last three decades. Asian American literary studies has also expanded rapidly. The rate of scholarly publications in the field sextupled from 1990 to 2014 and continues to accelerate. The growth of the corpus is a familiar theme in the field, but we have not confronted its methodological consequences.

The Asian American literary corpus is now too large for most scholars in the field to be familiar with in its entirety or to grasp through close reading alone. Deploying database construction, text mining, and quantitative analysis, this article is the first attempt to survey systematically and at scale the breadth of the Asian American corpus and the scholarship framing it. Scholars of Asian American literature have kept their distance from quantitative methods.2 The aversion is understandable. Tara McPherson notes a suspicion in ethnic studies fields that computational methods are complicit with the technology-fueled capitalism ravaging minority communities.3 As Richard Jean So, Hoyt Long, and Yuancheng Zhu have argued, this skepticism is further warranted by the dubious history of quantitative data use in studies of race. The categorical logic of computation, they add, seems to conflict with the goals of critical race studies to deconstruct racial categories.4 A more direct cause may be the failure of digital humanities (DH) regarding race. DH work has been plagued by unreflective whiteness, only recently beginning to engage with racial difference and minority literatures after prominent critiques made it difficult to ignore the issue much longer.5

This article is the opening report from a long-term project that strives to bridge the separations between Asian American literary studies and digital humanities. It aims to show how DH methods, when combined with the critical consciousness of ethnic studies, can yield rich benefits in both directions. Text mining methods require defining the corpus. How to define Asian American literature has been a longstanding debate plagued with the specter of racial essentialism. Instead of taking the racialized category of Asian American literature as a given, we concluded that the construction of the corpus should be the first object of inquiry. We built a dataset to examine the contested history of constructing the Asian American corpus in Asian Americanist scholarship. We ask, how have the definitions, boundaries, and internal structures of this corpus transformed over time? Many scholars have noted the field's problematic reliance on the raced bodies of authors as a defining criterion.6 Others argue that Asian American literature should be defined by racial and political content or that we should understand "Asian Americanness" as a formal quality.7 We suggest that this theoretical debate be grounded in an examination of the concrete corpus-building practices of scholars. On one important level, Asian American literature is the body of texts that have been discussed as Asian American by the hundreds of scholars who have helped institutionalize and legitimize the idea of this literature. Publication by publication, scholars in Asian American studies have made concrete choices about which works deserve attention as Asian American literature. These choices have accreted over decades into a corpus that has shaped the idea of Asian American literature.8 This shaping demands scrutiny.

Ethnic studies has reflected deeply on the problems of corpus building at large and of ethnic corpora in particular, especially the selective and fraught corpora we call canons. David Palumbo-Liu argues that critics should be conscious of an ethnic canon's "historical and ideological constructedness."9 He insists that we be wary of multicultural projects that accommodate ethnic texts in the dominant canon as a way to "neutralize conflict" or, as Lisa Lowe explains, to have differences and inequalities fall away through inclusion in universalized criteria of art.10 These arguments inspire our goal of examining the history of conflicts, differences, and inequalities in the construction of the Asian American canon. As Asian American literary studies has become institutionalized and large enough to have its own internal canon, these calls to vigilance must put more stress on the field's own canon-building practices.

This is an opportunity for cross-field dialogue. The critical consciousness ethnic studies brings to corpus construction could enrich digital humanities projects as they wrestle with the biases in the digital corpora on which so many projects rely. As we hope to show, DH methods can in turn help ethnic studies fields be more rigorous in examining their own corpus-building practices. Scholars of Asian American literature can easily rattle off some authors and works that they know to be part of the canon — Maxine Hong Kingston and Carlos Bulosan — but such views of the scholarly landscape are largely anecdotal and unsystematic. (See table 1 for the top ten most studied authors and texts). To examine the field's scholarly choices for their aggregate effects and systemic inequalities, quantitative methods are powerfully revealing, even necessary.

Table 1: Most studied authors and texts over the history of Asian American literary studies.| Author | Rank | Text | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maxine Hong Kingston | 1 | The Woman Warrior | 1 |

| Chang-rae Lee | 2 | Native Speaker | 2 |

| Frank Chin | 3 | American Is in the Heart | 3 |

| Carlos Bulosan | 4 | China Men | 4 |

| Edith Maude Eaton | 5 | Obasan | 5 |

| Jessica Hagedorn | 6 | The Joy Luck Club | 6 |

| Theresa Hak Kyung Cha | 7 | Fifth Chinese Daughter | 6 |

| Joy Kogawa | 8 | Dogeaters | 8 |

| Jhumpa Lahiri | 8 | Tripmaster Monkey | 8 |

| Amy Tan | 8 | Dictée | 10 |

| Jade Snow Wong | 11 | A Gesture Life | 10 |

| Lois-Ann Yamanaka | 11 | ||

| Karen Tei Yamashita | 11 |

The findings we present here focus on three key areas of debate and inequality in Asian American literary studies: the historical breadth of the corpus, disparities among Asian American ethnic groups, and gender balance. We first offer data that confirm a trend many scholars have sensed — the dominance of contemporary literature in the field's attention. Confirmatory findings might seem redundant, but they have particular value in digital humanities studies; they give researchers more confidence that their methods are sound while reinforcing the reality that knowledge production is often incremental. Our data confirm the contemporary bias while adding new context: the field has always focused on contemporary texts. This history suggests the major corrections it would take to rebalance scholarly attention across Asian American literary history. Our other findings reveal developments that the field has not recognized. We show ethnic inequalities that trouble the narratives the field has told about its diversification. The literatures of ethnic groups aside from the most visible ones hold only a sliver of the field's attention. Meanwhile, the overrepresentation of Chinese and Japanese American literatures persists. We reveal the dramatic ascension of Korean American literature and a reconfigured East Asian American hegemony in the field: Chinese, Korean, and Japanese American literatures, in that order. This reconfiguration has been enabled by a troubling decline in studies of Filipinx American literature, which was once central to the field. Our data indicate that much Filipinx American literature is today studied outside the panethnic Asian American framework entirely. Meanwhile, the conflation of Chinese American literature with Asian American literature as a whole has intensified. The data raise questions about the extent to which the field's rhetoric of diversification has masked persistent and emergent inequalities in our critical practices. The final section presents more encouraging data that show the surprising degree to which Asian American feminist critiques have transformed scholarly attention. The field has reversed the dominance of male writers to place female writers at the center of Asian American literature. It's a heartening development illustrating what's possible when we confront inequalities honestly and respond with sustained interventions.

Tracking Scholarly Attention

Comprehensively tracking the distribution of scholarly attention in a field is difficult, since one cannot directly measure the thing itself. The database we've built is a useful proxy for the dynamics of scholarly attention in Asian American literary studies, but it is a proxy. We hope readers keep this in mind. Building upon data from the MLA bibliography, we aimed to collect the set of scholarship on Asian American literature and the primary texts studied in that scholarship, in effect which texts scholars have constructed as Asian American. In 2016, we began collecting data on all the scholarly publications indexed in the bibliography that include "Asian American" or "Asian America" in their title or abstract.11 We also included all the works of literary scholarship published in two leading journals in the field, Amerasia and The Journal of Asian American Studies.12 Our database encompasses hundreds of publications from the early years of the field up to 2016, including articles, book chapters, books, and dissertations.13 We then wrote a script to scrape the MLA bibliography for the titles of primary texts studied in each piece of scholarship. We supplemented this data by manually examining many scholarly works.14 The result was a database of which primary texts have been studied under the Asian American rubric.

The next stage was collecting metadata on each primary text so we could see what kinds of literature and authors the field has emphasized. For each scholarly citation of a primary text, we recorded the title of the scholarly work, scholar name(s), year of publication, and publication venue (for book chapters and articles). Collecting metadata on the primary texts involved drawing on reference works and scholarship in Asian American literary studies, biographical sources, and online articles. For each primary text cited, we collected the title, year of publication, author(s), genre, publisher, bestseller status, and major awards. On authors, we collected a wide range of demographic and biographical information: gender, ethnic group/national origin group, race, nativity, country of birth, year of birth, immigrant generation and year of immigration (if applicable), major locations of residence, level of formal education, where they earned their highest degrees, whether they earned an MFA, whether they taught in a university and which one, and any major awards.15 Together, these metadata fields give us numerous ways to examine how the scholarly attention of the field may cleave to particular axes of social difference, emphasize certain kinds of literature, and highlight specific forms of distinction. While there is not space in this paper to present all the findings this database reveals, we plan further publications and hope to make the database an accessible, collaborative resource that scholars can draw on and add to.

As a proxy for scholarly attention our database comes with several limitations. First, the MLA bibliography is not a complete record of literary scholarship. There are likely works of Asian American literary studies not indexed in the bibliography (or published in the two leading journals) that are not represented in our data. There is, for instance, very little Asian American scholarship from the 1970s in the bibliography. Partly, this is because the amount of scholarship in the field at the time was very small. But another factor may be that some scholarship was published in venues not indexed in the bibliography. Despite its gaps, the MLA bibliography remains the largest record available of literary studies and offers an important picture of the field. A second limitation is that records in the bibliography do not always list the primary texts studied. To address this we manually examined all the monographs with "Asian America(n)" in their titles or abstracts to make sure we recorded all the primary texts they discuss. It was impractical to do the same for every article and book chapter we identified. It's likely then that we missed some discussions of primary texts in articles and book chapters for which the MLA bibliography has incomplete primary text data. Based on tests in which we split up our database to have metadata from books in one group and metadata from articles and book chapters in another, there is, in aggregate, no substantial difference between the kinds of primary texts and authors these two groups of scholarly sources discuss. The differences are very slight so the major trends and results about period, ethnicity, and gender we present here would not change if we were able to include primary text citations from all the articles and book chapters listed in the bibliography. A third limitation is that there are scholarly works that discuss literary texts as Asian American but are not captured here because they do not use the term in their titles or abstracts. To catch all these instances is not possible, for it would require searching the full texts of all published literary scholarship for the term "Asian America(n)." No such comprehensive full-text access exists. While we do not capture all scholarship discussing literature as Asian American, we focus on the large and meaningful set of scholarly works that foreground their Asian American concerns by flagging the term in their titles and abstracts. These are the scholarly works that make explicit and prominent claims to contributing to the understanding of Asian American literature.

A Contemporary Literature

The data we've collected let us compare key debates in Asian American literary studies and central narratives the field has told about its transformations to the concrete choices of critical attention that scholars have made. One important debate has focused on the periodization of Asian American literature. In the field's early years, scholars and writers sounded the urgency of recovering older texts and recognizing the longer scope of Asian American literary history.16 In the 1990s, during the field's rapid growth, Shirley Geok-lin Lim and Amy Ling claimed that the field was focused simultaneously on the "recuperation of overlooked texts" and "the ongoing interpretation" of recent works.17 But other scholars felt the scales were tipping toward the contemporary. In 1998, Jinqi Ling argued in response that "cultural history 'can develop only contrapuntally,' so . . . we must constantly be rereading earlier texts."18 We suspect that many in the field would say that the scales have tipped even more decisively toward the contemporary in recent years. Our metadata confirm that this is true, but not because of any systemic change in the field's practices. In fact, the field has always focused on contemporary literature and literature of the very recent past. We calculated the lag time between when a text is published and when it is discussed in a work of scholarship. Over the history of the field, this lag time has consistently hovered around 15 years with a standard deviation of 12 years. In other words, in any given period of Asian American literary studies, the bulk of critical attention has focused on texts published from 3 to 27 years earlier, with the largest concentration on texts around 15 years old. The 3-year period suggests a soft minimum amount of time for a new work to circulate into critical consciousness and for scholarship to go through the writing and publishing cycle. Meanwhile, the 15-year median suggests that most scholarship focuses on recent literature that has had more time to gain a critical reputation.

The lag time has not changed, but what has changed is the explosive growth of scholarship in recent years. The intersection of this recent acceleration with the consistent window of attention results in the majority of all Asian American scholarship being focused on today's contemporary literature, texts from the 1990s and 2000s. Figure 1 shows the distribution of critical attention to literature from different time periods over the entire history of the field. Of the texts we have studied, 82% were published from the 1970s onward and texts from the 1990s onward account for 52% of all citations. As of 2016, the median publication date for the Asian American corpus was 1991. These findings show the extent to which the outpouring of scholarship in recent years determines the centers of Asian American literary studies as a whole.

The field could justify this focus on late twentieth- and twenty-first-century literature by pointing to the rapid increase in Asian American literary production in this period, but we have no good measures of that production. If, alongside that motive, we still feel that the longer history of Asian American literature is important, the data show that it would take unprecedented adjustments to the field's tendencies to distribute attention more evenly across this history. Counteracting the historical unevenness built up in the last few decades of proliferating, contemporary-focused scholarship would be a major undertaking.

Ethnic Inequalities

The data reveal troubling developments regarding a fraught issue in Asian American studies: which ethnic groups are addressed by the panethnic term "Asian American." This constructed term attempts to encompass many different ethnic groups with roots in dozens of different countries, each with distinct histories, cultures, languages, and experiences. As a result, the ethnic tensions within the term "Asian American" have been intense, from its beginnings as a political movement to the contemporary period when Asian American populations are rapidly diversifying and placing more pressure on the idea of a unified community. Asian American literary studies has been embroiled in these conflicts as it has undertaken "the controversial dialogue of constituting an 'Asian American literature'" whose boundaries were set by the "inclusion or exclusion" of the literatures of specific ethnic groups.19

The dominant narrative the field has told about ethnicity begins with a narrow ethnic focus in the field's early years. Since then, the story goes, the field has expanded into a much more inclusive body of literature and scholarship. Looking back at the anthologies that defined the field, the assessment of narrowness seems justified. Asian-American Authors (1972) and Aiiieeeee! (1974) characterized Asian American literature as Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino American literature.20 Landmark publications in the 1980s such as Elaine H. Kim's Asian American Literature widened the corpus to include Korean American literature.21 The push to ethnically diversify the corpus became a central concern in the 1990s, and there was a sense that the field's corpus was transforming accordingly.22 In 1996's Immigrant Acts, Lisa Lowe described Asian American literature as an "unfixed body of work whose centers and orthodoxies shift as the makeup of the Asian-origin constituency shifts."23 Susan Koshy, writing in the same year, sensed the narrative of greater inclusiveness but challenged the idea that expanding inclusion was adequate. If the field simply adds on new literatures and groups without shifting old paradigms and established centers, then inclusion simply becomes a facile celebration of diversity rather than a reconfiguration of the field.24

Despite Koshy's critique, the narrative of greater inclusivity spread. By the late 1990s, diversification seemed a fait accompli in many accounts. King-Kok Cheung in 1997 claimed that the field was no longer teaching and studying the same works, "mostly by Chinese American and Japanese American writers," again and again.25 In 1999, Sau-ling Wong and Jeffrey Santa Ana concurred: "the strong presence of Filipino, Korean, various South Asian, and Vietnamese and other Southeast Asian writers have eroded the dominance of the Chinese and Japanese in earlier periods."26 And Karen Chow in 2001 concluded that "the scope of ethnic representation has become much more diversified."27

There is however a difference between committing to a more ethnically inclusive corpus on the level of rhetoric and the hard work of shifting critical practices on the ground. Our metadata reveal that the narrative of diversification has been too sanguine.28 The distributions of critical attention have not aligned with the field's rhetoric, and the project of an inclusive corpus is still far from complete. In some respects, critical attention has shifted. The data show that the field has devoted smaller shares of attention to Japanese American literature and increased its study of the literatures of some growing ethnic groups. Attention to Indian American literature has increased to about 10% of scholarly citations in the 2010s, and attention to Vietnamese American literature has grown to 6% of all studies today. The last twenty years have also seen the beginnings of attention to the literatures of Cambodian Americans, Pakistani Americans, and other emergent ethnic groups.

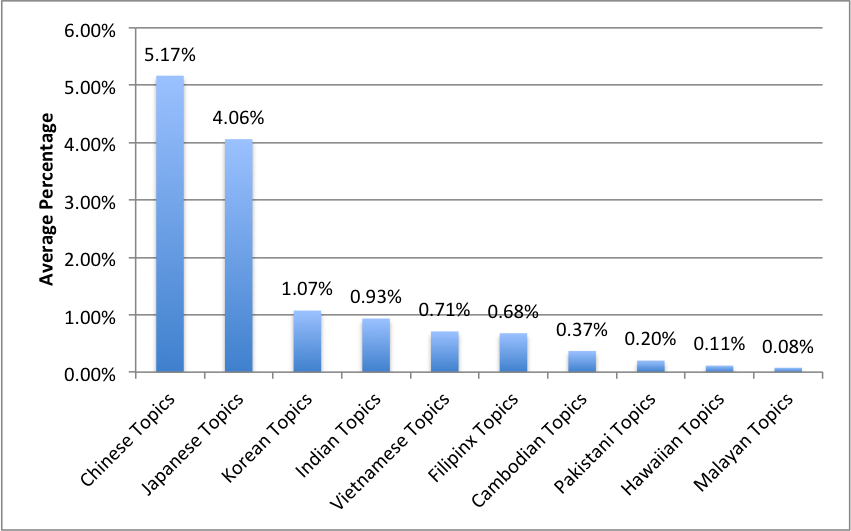

But in the bigger picture of the field, these advances in diversification are eclipsed by old ethnic inequities that remain and new ones that are emerging. As figure 2 shows, the corpus as defined by the overall history of the field remains highly stratified by ethnicity, with the top two groups unsurprising. Recent scholarship also reveals disparities, demonstrated in figure 3 by the attention devoted to the literatures of different ethnic groups over the decades of scholarship. This distribution remains unequal even in the 2010s. Today the ethnic literatures receiving substantial critical attention are (in order): Chinese, Korean, Japanese, then Indian, Filipinx, and Vietnamese, with the top three commanding nearly 80% of all attention. Old hierarchies persist. Chinese American literature still commands central attention (37% of citations). This is a slight improvement over earlier periods when it accounted for 40-50% of critical attention. But it remains highly disproportionate.

By disproportionate, we mean that one crucial way to examine ethnic inequalities in the field is to compare the distributions of critical attention to the population distributions among Asian American ethnic groups. The idea that demographic proportionality should be an important consideration in directing scholarly attention may be controversial, so let us elaborate on it before analyzing the data in more detail. Proportionality raises many tough questions, a full consideration of which lies beyond the scope of this essay. We lay out here a few arguments in the hopes of beginning a wider discussion of this issue in the field.

While proportionality may strike some as an overly deterministic relation between social demographics and corpus construction, Asian Americanists calling for a more inclusive corpus have long posited a direct relationship between the two. As we mentioned above, Lisa Lowe wrote that Asian American literature "shift[s] as the makeup of the Asian-origin constituency shifts."30 King-Kok Cheung agreed: "the altered demography in recent years and the prominence of some immigrant writers are beginning to unfix the border of Asian American literature."31 In such formulations, demographic change appears as a causal agent reshaping the Asian American corpus. Moreover, the language of "constituency" implies a model like political representation in which the scholarly field has a responsibility to be representative of its constituents, the Asian American population (an idea familiar from the community-oriented origins of the field). In a constituent model, proportional representation would make sense, but it's not clear whether these scholars would endorse this implication. This lack of clarity is a general problem in the field. We've often posited some kind of close relationship between Asian American demographics and the inclusive Asian American corpus we're building, but this relationship has been vaguely defined.32 It's revealing to compare the field's vagueness to a particularly explicit outlier, the 1989 Asian American women's anthology Making Waves. Although the editors "aimed to have equal representation of all ethnic groups," they concluded that they "found it difficult to obtain written materials from some of the groups, especially the new and emerging ones" and thus they "could not be absolutely inclusive."33 They defined inclusion as equal text selections from all Asian American ethnic groups. Setting such an explicit goal had an important benefit: it allowed them to assess whether they fell short of the goal. Has the avoidance of explicitly defined goals allowed Asian American literary studies to avoid scrutinizing whether we've failed at inclusion?

Demographic proportionality or numerical equality may be blunt definitions of inclusion, but bluntness may be preferable to the vagueness that has helped the field defer a tough conversation on what exactly we mean by inclusion. These definitions offer explicit answers to important questions that the field has not clearly answered. What are our goals for the more inclusive Asian American corpus that we say we want? What do we mean by inclusion and what does it look like? What would the Asian American corpus and Asian American literary studies look like if inclusion were achieved? How do we measure and assess our progress? And how do we know if we are failing? A measurable check like proportionality can prod the field to confront these questions more explicitly.

Of course many motives beyond the desire to be responsive to ethnic demographics compel the field's scholarly attention. Considerations of artistic quality, historical significance, social impact, and critical interests also shape which texts we choose to study. Many of these forms of value are more congruent with the pressures of academic autonomy and legitimization that the field negotiates than the political ideal of reflecting the Asian American constituency.34 We can hypothesize then that these factors could drive demographically disproportionate patterns of scholarly attention.35 But while acknowledging the multiple factors at play, the field should be wary of accepting these other factors as sufficient stopping points for questioning why the corpus we've built is ethnically disproportionate. If the field's choices of texts reflect our assessments of various values, why would our assessments of the artistic quality, historical significance, social importance, and critical interest of texts break down so unevenly along ethnic lines? Are we comfortable, for example, suggesting that Chinese American literature exhibits vastly more artistic achievement and historical, social, and critical interest to Asian American studies than Filipinx American literature (six times more according to the most recent decade of attention data)?

Claims about artistic quality, historical significance, and social importance were used in the canon wars of the 1980s and 90s against activists who observed how disproportionate the Western canon was to the ethnic and gender demographics of university students and American society.36 Asian American studies has repeatedly contested the traditional canon's definitions of value and challenged "universal" standards to expose the ways these standards grow out of specific conditions of power that allow dominant groups to expand the qualities of their literatures into universal standards.37 Given the history of the canon wars and Asian Americanist challenges to the canon's values, there's reason to question ourselves if our instinct is to call up the old standards of aesthetic value and historical importance to justify why the corpus we have built is ethnically disproportionate.

In the spirit of not taking these old standards for granted, we suggest introducing demographic proportionality as an accountability metric. Periodically gathering data on proportionality can offer an important baseline. When the data reveal deviations from proportionality, Asian Americanists can investigate what's behind this deviation, debate whether it's justified, examine the field's standards and whether inequalities of power have allowed specific sensibilities and concerns (for instance those built around Chinese and Japanese American literatures) to become "universal" standards across the field. While we do not believe that demographic proportionality should be the central value directing scholarly attention, we believe proportionality deserves serious debate within the field, not least for the questions of goals, definitions, assessments, and accountability that it raises.

Returning to the data with this accountability metric, we can compare changes in scholarly attention (figure 3) to changes in Asian American demographics (figure 4). Their divergences make clear that the field has too readily assumed that critical diversification reflects demographic diversification. That assumption has obscured the hard work that remains to be done. Since 1980, the Chinese American population share has hovered around 20-25% yet their share of critical attention has been in the 40% range or higher. This share seems to be slowly decreasing but it is still far from approaching proportionality. Historically Chinese Americans and Chinese American literature accounted for a larger share of Asian American communities and cultural production. If the field were still studying older literature, then this might explain the higher share of attention in the present. As we discussed above however, critical attention focuses predominantly on the contemporary, so attention to older literature only accounts for a small portion of the Chinese American share. Among all citations of works published since 1970, Chinese American authors account for 41%. The field has long recognized the dominance of Chinese American literature, but we need to see that it persists well after the field's ostensible diversification. Much as Susan Koshy warned, established centers of the Asian American corpus endure even as other ethnic literatures are brought into the edges of the conversation.

The shifts in attention to Japanese American literature are more promising from the standpoint of proportionality. In 1970 Japanese Americans were the largest demographic subgroup, but in 2010 they were the sixth most populous. Correspondingly, critical attention has started to track downward. Japanese American literature is now the third most studied literature. That said, their share of critical attention remains disproportionately high. Japanese Americans claimed 17% of citations in the 2010s while making up 8% of the Asian American population. As with Chinese American literature this disproportion is not primarily a result of attention to older works. Most attention to Japanese American literature (85%) in scholarship from the 2010s focuses on works published since 1970.

That Chinese and Japanese Americans hold the centers of Asian American literature is a longstanding story continuing into the present. The ethnicity metadata also reveal new inequities and reconfigurations that the field has not fully recognized. As attention starts to trickle to the literatures of emergent ethnic groups, a new divide is visible between the six most studied ethnic groups and the rest. As figures 3 and 4 show, Pakistani, Cambodian, Burmese, Sri Lankan, Indonesian, Laotian, and Singaporean Americans among many others, now account for 12% of the Asian American population but only 2% of our scholarly attention. Before 2000, there was virtually no scholarship on their literatures, so 2% is an improvement. Given the recent growth in these populations, it's possible that this upward trend will continue. But as we discuss below, there are reasons to doubt that this will happen without concerted changes in the field's practices.

The literatures of emergent ethnic groups are not the only ones struggling for attention. One of the most troubling developments the data reveal is the case of Filipinx American literature, which has been part of the Asian American corpus from its founding. In the early days of the field, Filipinx American literature commanded central attention. It was the second most studied literature in the 1980s with 33% of citations. But this foundational position has eroded, as figure 3 shows. By the 2000s, Filipinx American literature had dropped to fifth place (8% of citations) and today it is nearly tied with Vietnamese American literature at 6% of citations. This dramatic decline in attention contradicts the continued prominence of Filipinx Americans in the Asian American population. Since 1980, Filipinx Americans have been the second largest subgroup, accounting consistently for 20% of the population (figure 4). The field must investigate why there has been such a precipitous drop in scholarly attention when there has been no change in Filipinx Americans' share of the Asian American population. We suspect the decline points to inequalities within Asian American studies that have marginalized Filipinx Americans.

These inequalities are not news to Filipinx studies scholars. Oscar Campomanes wrote in 1992 that the status of Filipino Americans as the forgotten Asian Americans had become a tired theme in Filipino studies. He argued that as an exile literature, and because of the colonial relationship between the Philippines and the U.S., Filipino American literature could not fit within the immigrant paradigms of Asian American studies.38 Reflecting in 2006, Rick Bonus pointed to the 1998 Blu's Hanging controversy as a "climactic moment" in the eroding relationship between Filipino and Asian American studies. When the Association for Asian American Studies presented a literary award to a novel that many Filipino American scholars believed trafficked in anti-Filipino racist tropes, the moment raised "larger and uneasy questions" about the place of Filipino voices in the field.39 The book controversy was a culmination of long-running marginalization and anti-Filipinx racism that the field had failed to address. The metadata corroborate what these Filipinx studies scholars felt in the 1990s. As figure 3 shows, the 1990s saw the most precipitous decline in attention to Filipinx American literature.

The conspicuous decline in attention to Filipinx American literature occurred as the field was increasing its attention to other ethnic literatures, corresponding in particular to the dramatic rise of Korean American literature. As figure 3 shows, the growth of Korean American literature is accelerating. From barely cited at all, it has become the second most studied literature, overtaking Japanese American literature in the 2010s. This trend also contrasts with demographic patterns. Since 1980, Korean Americans have remained a steady 10% of the Asian American population (figure 4), but in this period their share of critical attention has grown to over 21% of the field. The fates of Filipinx and Korean American literatures have been nearly mirror images of each other. In the 1980s, Filipinx American literature was the second most studied and Korean American literature a distant fourth. Today, Korean American literature holds the second position while Filipinx American literature has dropped to fifth. All the while their shares of the population have remained unchanged. This raises important questions about the field dynamics that have forgotten Filipinx American literature while consecrating Korean American literature. Those familiar with Korean American literature might ask, is this rise simply a result of the critical success of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha and Chang-rae Lee in recent decades? The answer is largely no. While Cha and Lee account for about 35% of citations of Korean American literature, there are many other authors attracting scholarship such as Susan Choi, Nora Okja Keller, Julia Cho, Younghill Kang, and many more.

Through these shifts in attention, the field has constructed a new East Asian American hegemony for the twenty-first century. As Japanese American literature declines in prominence and Filipinx American literature has fallen from the centers of the field, the dominant formation of Asian American literary studies is now Chinese, Korean, and Japanese American in that order. Together, these East Asian ethnic groups claim 76% of the citations in the 2010s. As figure 5 shows, this corresponds with East Asian American shares of attention across the field's history.

Controverting the field's narratives of increasing diversification, things were actually better in the 1980s when East Asian American literatures accounted for 67% of citations. East Asian Americans have long dominated the image of the Asian American community, such that Asian American racialization is conflated with the specific racialization of East Asian Americans, and Asian American politics has routinely revolved around the interests of East Asian American groups. The field may tell itself that it has diversified ethnically, but on this measure of intra-Asian regional dominance, things have changed without changing.

Filipinx Americans and other ethnic groups are marginalized in Asian American literary studies, but their literatures continue to inspire rich scholarship. Examining how these bodies of scholarship frame themselves, we can see the failures of the panethnic category of Asian American literature as an intellectual and institutional home. Yến Lê Espiritu argues that emergent or marginalized Asian ethnic groups may feel unrepresented by the panethnic umbrella and decide to pursue their interests outside of this framework.40 This is happening in Asian American literary studies. For example, many studies of Cambodian American and Filipinx American literatures are framed in ethnic specific rather than panethnic terms. We examined the MLA bibliography for studies explicitly framed as Cambodian American and compared the number to studies of Cambodian American writers framed under the Asian American label. There are three times as many citations of Cambodian American works under the ethnic specific label than under the panethnic label. Scholars such as Cathy Schlund-Vials, Jonathan H. X. Lee, and Mary Thi Pham have launched a growing field of Cambodian American literary studies that examines the specific histories of war, genocide, and reparative justice work that this literature engages.41

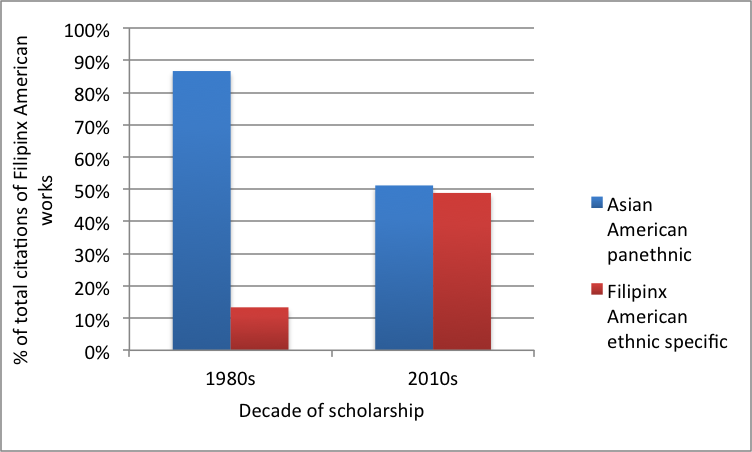

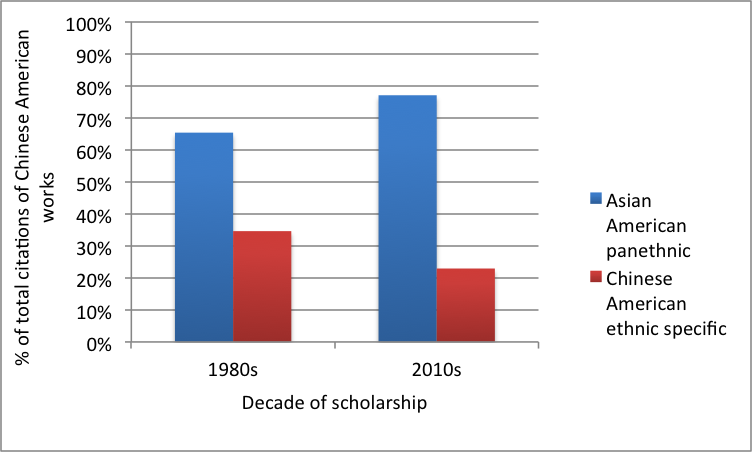

Unlike Cambodian American literature, Filipinx American literature is not emergent, so its relationship with the panethnic category over time is revealing. As figure 6 shows, very few studies of this literature appeared under the ethnic specific label in the 1980s, and 87% of the scholarship was housed under the panethnic rubric. But from the 1980s to the 2010s, Filipinx American literary studies shifted from a firm stance within the Asian American rubric to having one foot outside of Asian American studies. Today only half of the studies of Filipinx American writers occur under the Asian American rubric. Contrast that with studies of Chinese American literature (figure 7).

In the 1980s, 65% of studies of Chinese American writers occurred under the panethnic rubric. But unlike with Filipinx American literature, the identification of Chinese American literature with the panethnic rubric has only grown stronger. In the 2010s, studies of Chinese American writers are three times as likely to occur under the panethnic rubric as under the ethnic specific rubric. The synecdochic relation of Chinese American literature to Asian American literature has intensified in the period of the field's ostensible diversification while Filipinx American literature increasingly finds its home outside the panethnic category.

We must ask why many studies of "other" Asian American ethnic literatures cannot or choose not to claim the panethnic category. If we listen to Filipinx studies scholars, their reasons are clear. Epifanio San Juan, Jr. proposed in the 1990s "that Filipinos and their practice of cultural production no longer be subsumed under the rubric of 'Asian-American,'" and crucially, he added, "this has, de facto, taken place through exclusion anyway."42 Excluded from the centers of the panethnic category and enduring bias, many Filipino studies scholars have abandoned the panethnic term. This was necessary to allow "the study of Filipino social formations on its own terms," which has not been possible within Asian American studies.43 The 2016 landmark anthology Filipino Studies: Palimpsests of Nation and Diaspora celebrated the emergence of Filipino studies "as a trenchant and vibrant academic presence."44 Failed by the ethnic inequalities structuring Asian American studies, these scholars have built a thriving independent field.

Filipinx studies scholars have not been alone in questioning the panethnic label. As part of the rhetorical shift of Asian American studies toward diversification, scholars have deconstructed the panethnic category and highlighted the differences it covers. Kandice Chuh's Imagine Otherwise (2003) was one of the most influential arguments in this vein. Revisiting Chuh's argument in light of this data is sobering, as her book pointed to a path the field did not take. The opening chapter, subtitled "remembering 'Filipino America,'" envisioned a reconfigured Asian American studies built around this formation. Filipino America is subject to "categorical flux" between national, colonial, and diasporic frameworks, and the colonial history of Filipinos fosters skepticism of U.S. national identification. Filipino racializations highlight the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and empire. For all these reasons, Chuh argued that Filipino America "is an ideal construct around which to organize Asian American studies. It is . . . an explicitly antagonistic force that refuses to allow Asian American studies to solidify the boundaries of what constitutes its proper objects of knowledge." On a theoretical level, the field has been heavily influenced by Chuh's proposal of a "subjectless" Asian American studies, but this shift as practiced has not only not centered Filipinx America, it has also coincided with an intensified forgetting of Filipinx America.45 Has the field's deconstruction of Asian American identity, which helped sideline goals of identity and inclusion, inadvertently helped us overlook the continuing problems of identity and inclusion facing marginalized groups like Filipinx Americans?46 Scholars have for good reason critiqued the framework of inclusion as no substitute for radical projects of justice. But perhaps the field's recent critiques of inclusion are based in part on the false narrative that we already accomplished diversification in the 1990s. If so, then inclusion is passé and it's time to move onto other models. But the field never achieved inclusion.

For the literatures of emergent ethnic groups, there is a cruel irony to the anti-identitarian deconstructive turn of the field. These literatures, which have never enjoyed a central claim to the Asian American category, are emerging into attention in the very period when the field is deconstructing the panethnic label and emphasizing specificity instead. Despite the deconstructive critique, the number of studies invoking the panethnic label has accelerated. Ironically, then, the deconstruction of the panethnic category and the call for specificity may have resulted in marginalized ethnic groups being studied under specific labels while the panethnic category continued unabated to serve dominant ethnic groups. A cynical read could suggest that the deconstructive call for specificity was an effective way to retain the Asian American category's internal hierarchies. Chinese American literature has only become more conflated with the panethnic category during this period. Meanwhile, subfields focused on literatures with far less power have run with the call for specificity, realizing perhaps that they would not be recognized within the Asian American corpus as currently structured.

Going forward, the field must wrestle with these troubling developments in ethnic inequality. The genuine inclusion of Filipino social formations, as Antonio Tiongson, Jr. argues, would require wholesale reconfiguration of how the field is defined.47 His argument applies as well to many other marginalized ethnic groups and literatures. With his point in mind, the ethnicity metadata over time suggest that genuine inclusion is not a facile or easy project. Inclusion on the level of the field's concrete and systemic critical practices would require transforming the field's central frameworks and internal structures. Could the field shift so that taking the concerns of Pakistani American or Laotian American literatures as representative of Asian American literature would feel unremarkable? Could we learn from Filipinx studies how to center colonial displacements, not just narratives of immigration? Could we listen to Cambodian and Hmong American studies and center intranational conflicts and secret warfare in Southeast Asia as much as we do World War II and Vietnam? Could West and South Asian American studies help us focus on ethnoreligious racialization and the "War on Terror" as centrally Asian American struggles? Perhaps. But the first step will be looking past our field's optimistic narratives of diversification to confront how we've concretely built ethnic inequalities. For that step, data-driven self-scrutiny will be a powerful tool.

Thematic Inequalities

So far this paper has focused on metadata about texts and authors, but digital humanities offers tools for looking into the contents of texts as well. Having identified the Asian American corpus, we've begun building a digitized version for content analysis. For the question of ethnic inequalities, this digitized corpus lets us examine whether the unevenness of the authors included in the corpus constructed by scholars results in thematic inequalities. Of course the ethnic identities of authors need not dictate their thematic concerns, but we wanted to explore the possible effects.

Constructing digital corpora is a laborious bottleneck in digital humanities research. The HathiTrust Research Center has helped enormously with this problem by making even texts under copyright available to many scholars for non-consumptive text mining. Of the around 700 texts cited in Asian American literary studies, about 575 could be readily analyzed through our text mining methods.48 Hathi's collection contained about 60% of these texts. We digitized nearly 100 additional texts ourselves. The digital corpus we've built represents 70% of the readily analyzable texts cited in the field. It's not complete but it's close. Figure 8 shows the ethnic distribution of the authors represented in the digitized corpus, which is close to the distributions in the citations reported in figure 2.49 Here there are slightly fewer Korean and Filipinx authors and slightly more Indian and Vietnamese authors than in the metadata analysis above.

We used topic modeling to explore thematic trends in the digitized corpus. A well-established text mining method, topic modeling categorizes a corpus of documents into a given number of word clusters, or "topics." These topics are calculated statistically based on how words tend to occur together within the corpus. The algorithmically-generated topics often contain patterns of words with related meanings that are interpretable as themes — although it is important to note that the algorithm itself does not assign thematic labels to topics. The researcher decides if a topic holds thematic significance, which is the most subjective part of the process.

We used the popular software package MALLET to build a model of 400 topics for the digitized corpus.50 MALLET created a numbered list (in no particular order) of those 400 topics and the words within each topic. MALLET presents the words in a topic ranked by prominence, so looking at the top ranked words allows one to sense the thematic "center" of the topic. We examined the list of generated topics to identify ones affiliated with a specific ethnic group. Words from an Asian language, ethnic group names, and ethnically specific items, customs, historical events, and terms were most often what signaled ethnic affiliation. We were conservative in our identifications. If we could not explicitly pin down affiliation, we did not code that topic as affiliated with any ethnic group. For example, here are the 25 most prominent words assigned to topic 0:

church minister churches service congregation mission missionaries missionary chapel prayer building faith members services sermon missions choir pastor work religion hymn pulpit organ aisle christian

While topic 0 clearly pertains to themes of Christian churches and missionary work, it does not contain any ethnically specific language, so we excluded it from this analysis. On the other hand, here are two examples of topics that we coded as ethnically specific. Topic 67, which we interpreted as dealing with Filipinx rural life:

house brother town father son yard laughter hands cock carabao wine floor rice gate legs grass rope money girl ground tree land window presidencia ladder

And topic 107, which we interpreted as dealing with Chinese opium and gambling dens:

opium pipe tobacco pipes bowl chinese smoking drug cents smoke hop joint gambling dens places habit smokers union eating center joss highbinder needle smoker lower

Of the 400 topics, we found 111 to be ethnically specifiable.

In addition to the list of topics, MALLET also produces a percentage breakdown of each document into all 400 topics. The topic model analyzes each document in the corpus as being composed of each of the 400 topics in various proportions, i.e., topic 1 "makes up" 2% of the content of the document, topic 2 "makes up" 5%, and so forth. This proportional makeup measure shows how prominent each topic is in a document. Averaging a topic's proportional makeup in all the documents lets us see that topic's prominence in the whole corpus, in effect how important that theme is. We did this with the ethnically specifiable topics across the digitized corpus. Figure 9 shows those results, grouped by ethnic affiliation.

The ethnic inequalities we saw in the authorial makeup of the Asian American corpus are visible in the thematic content of the digitized corpus. Chinese and Japanese American themes dominate. The relative ranking of ethnic groups here is nearly the same as in our metadata analysis above, with two exceptions: Vietnamese American themes outweighing Filipinx American themes (likely the result of the slight overrepresentation of Vietnamese American texts in the digitized corpus) and Hawaiian and Malayan topics edging out the topics of other marginalized ethnic groups. Because the field has created an ethnically unequal corpus, the topics that appear as Asian American literary themes are skewed. The data do not show a deterministic connection between authorial ethnicity and thematic concerns; topics that weren't ethnically specifiable account for the vast majority of the content across the digitized corpus, demonstrating that Asian American authors write about many concerns beyond the ethnically specific. However, they do suggest that building a more inclusive corpus would widen the themes, histories, and concerns the field studies. For this project, there is more work ahead on this data to examine the specific themes centered and marginalized in the corpus. For the field, there is even more work ahead to reshape these inequalities.

A New Gender Landscape

The data on gender in the Asian American corpus are far more encouraging. They reveal the ways feminist interventions have reshaped the field and its corpus to be more inclusive of women writers. When the pioneering anthology Making Waves came out in 1989, there was a sense that there were not nearly enough prominent literary works by and about Asian American women. But feminist interventions were underway, driven by scholars such as Amy Ling, Shirley Geok-lin Lim, and Elaine H. Kim. Feminist critiques targeted the masculinist orientation that seemed to dominate the formative years of the field.51 By the 2000s, scholars sensed a changing landscape. In 2002, Helena Grice noted "a distinct emerging canon of Asian American women's writing."52 And in 2012, Leslie Bow reflected, "if it was once possible to have read everything published by Asian women in the USA, it is thus perhaps a sign of progress that such a project is now, if not impossible, at least inordinately time-consuming."53 From the critical and commercial success of writers like Monique Truong, Jhumpa Lahiri, Ruth Ozeki, and Susan Choi, it seems clear that Asian American women writers have become important not only to Asian American literature but also contemporary American literature at large.

The metadata reveal the surprising extent to which the feminist intervention has succeeded. As figure 10 shows, studies of male writers often outnumbered studies of female writers in the early decades of the field. But by the mid to late 1990s, scholarship began to focus consistently more attention on female writers, and this trend has continued. In the 2010s, citations of female writers outnumber citations of male writers 57% to 43%. While the ten most studied female writers account for 35% of the total citations of women writers, the distribution shows a long tail of attention to hundreds of women writers, extending far beyond a few prominent authors like Maxine Hong Kingston or Joy Kogawa. The mid to late 1990s was also the inflection point for the explosive growth of Asian American literary studies (figure 11). Asian American women's literature has not only been included in the field, it has also been central to the field's growth. A majority of the field's growth has been driven by interest in Asian American women's literature. This is reflected in the distribution of attention in the overall history of the field: women have received 55% of citations while men have received 45%.

Few examples in literary history show a corpus reversing marginalization so effectively, so we're under-equipped to make sense of marginalized literatures that become the new dominant. Chalk this up under the heading of good problems to have. The field must wrestle with how to theorize this transformed and complex position. While Asian American women writers are not dominant in American literature overall, they are growing in stature, and within the minority corpus of Asian American literature they have become the new center. Meanwhile, the social positions of many Asian American women have not kept pace with these advances in the fields of cultural and critical prestige. When social and cultural positions are so disarticulated, concepts of minority and dominant cultures cannot do justice to the new terrain. We need new vocabularies that can parse the differing positions of a "minority" literature in concentric, overlapping, but non-identical fields of cultural power and prestige, vocabularies that can relate these positions in non-aligned and unexpected ways to the contextually variant social positions of an intersectionally identified group. Asian American women's literary studies can pioneer these vocabularies not just for Asian American women writers but also for other cases in the future in which concerted interventions reverse the structures of a corpus.

This paper's quantitative history of the construction of Asian American literature reveals an uneven terrain of inclusion and emergent centers alongside retrenchments and new inequities. It shows that the debates over corpus construction as they intersect with social inequalities within and beyond Asian America remain as urgent as ever. The work of building the Asian American corpus we would want to see is far from over. But as the case of Asian American women's writing shows, transformations of the field are possible through concerted critique and effort. Despite the field's reservations regarding quantitative methods, such methods can be powerful allies in this effort. Their findings can make our field more transparent about power imbalances and more aware of the concrete progress we've made. That Asian American literature has grown too large for any one of us to grasp with established methods alone raises challenges, but it should be seen as an exciting period for a field that has come a long way. Working digital humanities methods into the field's repertoire gives us further tools to grasp the proliferating landscape of Asian American literature. Digital humanities is well versed in data-driven analytics for examining vast bodies of literature. When coupled with the theoretical rigor ethnic studies has brought to the problems of corpus construction, these tools can help us in examining not only the contents of bodies of literature but also how they came to be and how we might build their futures.

Long Le-Khac is assistant professor of English at Loyola University Chicago. He is the author of Giving Form to an Asian and Latinx America (Stanford University Press 2020). His work has appeared in American Literature, MELUS, Victorian Studies, and the Stanford Literary Lab pamphlet series.

Kate Hao is a master's student in Public Humanities at Brown University, studying public engagement, community-building, and literature.

References

- We are grateful to Tara Fickle, Sue-Im Lee, and Richard Jean So for their feedback on this essay. [⤒]

- There is work crossing Asian American studies and the broader world of DH. For a survey, see Anne Cong-Huyen, "Asian/American and the Digital|Technological Thus Far," Verge: Studies in Global Asias 1, no. 1 (2015): 100-108. Most of these projects however do not focus on literature. [⤒]

- Tara McPherson, "Why Are the Digital Humanities So White? Or Thinking the Histories of Race and Computation," in Debates in the Digital Humanities, ed. Matthew K. Gold (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 140. [⤒]

- Richard Jean So, Hoyt Long, and Yuancheng Zhu, "Race, Writing, and Computation: Racial Difference and the US Novel, 1880-2000," Journal of Cultural Analytics, January 11, 2019. [⤒]

- McPherson, "Why Are the Digital Humanities So White?"; Moya Bailey et al., "Reflections on a Movement: #transformDH, Growing Up," in Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, ed. Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 71-79; Amy E. Earhart, "Can Information Be Unfettered? Race and the New Digital Humanities Canon," in Debates in the Digital Humanities, ed. Matthew K. Gold (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 309-18. [⤒]

- See for example Susie J. Pak and Elda E. Tsou, "Introduction," in "Asian American Bodies of Knowledge," ed. Susie J. Pak and Elda E. Tsou, special issue, Journal of Asian American Studies 14, no. 2 (2011): 171-91. [⤒]

- Jennifer Ann Ho, Racial Ambiguity in Asian American Culture (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2015), 123-147; Colleen Lye, "Racial Form," Representations 104 (2008): 92-101. [⤒]

- Other areas of corpus-building are also important. Large-scale studies of how teachers have composed syllabi, of how publishers have marketed Asian American literature, and of how writers have negotiated the label of Asian American would all be invaluable. For how writers have thought about the label, see Min Hyoung Song, The Children of 1965: On Writing, and Not Writing, as an Asian American (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013). [⤒]

- David Palumbo-Liu, "Introduction," in The Ethnic Canon: Histories, Institutions, and Interventions, ed. David Palumbo-Liu (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995), 14. [⤒]

- Ibid., 6; Lisa Lowe, Immigrant Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 43. [⤒]

- This search also captured uses of Asian Pacific American and Asian Pacific Islander American. Though the bibliography includes an Asian American subject tag, we did not use it, because tags are added by the editors of the bibliography and not by scholars themselves. [⤒]

- Such pieces, we concluded, signal their engagement with Asian American literature through their choice of publication venue. [⤒]

- Since we focused on original scholarship on literary works, we did not include review articles. We did not count literary works published in journals or the inclusion of a text in a literary anthology as instances of scholarly attention, because our initial studies suggested that the literature published in journals and collected in anthologies is not the same as what scholars devote substantial attention to in their criticism. If an article about a primary text(s) was republished in another venue we counted both instances. We see this as the critical discussion of the text(s) receiving multiple instances of scholarly visibility. We did the same in cases in which a dissertation was revised into a book. [⤒]

- We focused on primary texts to which scholarly works devoted substantive attention. In practice, this meant looking for at least a few pages of analysis. [⤒]

- The availability of information for each metadata field varied. The analyses presented in this paper are for fields for which we have robust data. In each field were authors for whom we could not find information. We didn't include their citations in the analysis of that metadata category. These unknowns were often for little-known authors who may be more likely to come from marginalized demographics. Their absence from the analysis may skew the results toward more central groups. The potential error though is small. The percentage of unknowns range from 2.5-4%. We estimate the skewing to be 1.5-2.5% at most. [⤒]

- See, for example, Bruce Iwasaki, "Literature: Introduction," in Counterpoint: Perspectives on Asian America, ed. Emma Gee (Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center, 1976), 454-455. [⤒]

- Shirley Geok-lin Lim and Amy Ling, "Introduction," in Reading the Literatures of Asian America, ed. Shirley Geok-lin Lim and Amy Ling (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992), 3. [⤒]

- Jinqi Ling, Narrating Nationalisms: Ideology and Form in Asian American Literature (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 3. [⤒]

- Stephen Hong Sohn and John Blair Gamber, "Currents of Study: Charting the Course of Asian American Literary Criticism," Studies in the Literary Imagination 37, no. 1 (2004): 2. [⤒]

- Kai-yu Hsu and Helen Palubinskas, eds., Asian-American Authors (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1972); Frank Chin, et al., eds., Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian-American Writers (Washington: Howard University Press, 1974). One exception that included Pacific Islander literature as well is David Hsin-Fu Wand, ed., Asian-American Heritage (New York: Washington Square Press, 1974). [⤒]

- Elaine H. Kim, Asian American Literature: An Introduction to the Writings and Their Social Context (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1982). [⤒]

- Lisa Lowe, "Heterogeneity, Hybridity, Multiplicity: Marking Asian American Differences," Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 1, no. 1 (Spring 1991): 24-44; Lim and Ling, "Introduction." [⤒]

- Lowe, Immigrant Acts, 53. [⤒]

- Susan Koshy, "The Fiction of Asian American Literature," Yale Journal of Criticism 9, no. 2 (1996): 316, 323. [⤒]

- King-Kok Cheung, "Re-Viewing Asian American Literary Studies," in An Interethnic Companion to Asian American Literature, ed. King-Kok Cheung (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 1. [⤒]

- Sau-ling C. Wong and Jeffrey J. Santa Ana, "Gender and Sexuality in Asian American Literature," Signs 25, no. 1 (1999): 198. [⤒]

- Karen H. Chow, "Preface" in "Asian American Literature, Part 1: Complicating Hybridity, Ethnic Self-Representation, and Globalization," ed. Karen H. Chow, special issue, Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory 12, no. 1 (2001): ii. [⤒]

- For a multi-ethnic author, we counted one citation of that author as one citation for each of the ethnic groups with which they identify. [⤒]

- Sources: Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung, "Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States" (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2002); Jessica S. Barnes and Claudette E. Bennett, "The Asian Population: 2000" (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2002); Elizabeth M. Hoeffel et al., "The Asian Population: 2010" (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau, 2012).[⤒]

- Lowe, Immigrant Acts, 53. [⤒]

- Cheung, "Re-Viewing," 7. [⤒]

- One common description of the relation is an ambiguous language of reflection. See Kim, Asian American Literature, 214; Cheung, "Re-Viewing," 3. [⤒]

- Asian Women United of California, ed., Making Waves: An Anthology of Writings by and about Asian American Women (Boston: Beacon Press, 1989), i, x. [⤒]

- On these pressures, see Mark Chiang, The Cultural Capital of Asian American Studies: Autonomy and Representation in the University (New York: New York University Press, 2009), 9, 11, 68. [⤒]

- Of course factors beyond literary criticism may be relevant. Social structures of class, education, and profession unevenly shape which Asian Americans produce literature while biases within publishing affect which works are published. We hope that having data on ethnic disproportions can spur the field to investigate the structural causes within and beyond literary studies. We hope also that it pushes the field toward a desperately needed project: a comprehensive bibliography of Asian American literary publications. Without one, we cannot fully parse how much of the ethnic disproportions are due to biases within Asian American literary studies or beyond it. But even if a bibliography were to reveal unequal publication rates among different ethnic groups, that finding would not dictate how the field chooses to distribute attention across extant publications. Asian Americanists have not been interested in passively reflecting the biases in the publishing industry. Consider the most studied authors in table 1. Many of these writers received scholarly attention in part because they've achieved commercial success and mainstream prestige, but many others, such as Carlos Bulosan, Edith Maude Eaton, and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, have entered the Asian American canon through scholarly attention that bucked mainstream measures of success. The field is an active and often interventionist force in canonization, with the responsibilities that come with that role. As the field works toward getting better data on the broader factors feeding into ethnic disproportions, we should not defer confronting the potential sources of bias within our control. [⤒]

- See, for example, Dinesh D'Souza, Illiberal Education: The Politics of Race and Sex on Campus (New York: Free Press, 1991), 75, 67. [⤒]

- Palumbo-Liu, "Introduction," 2. Some critics have prioritized political over aesthetic value. See Bruce Iwasaki, "Response and Change for the Asian in America: A Survey of Asian American Literature" in Roots: An Asian American Reader, ed. Amy Tachiki et al. (Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center, 1971), 89-100. Others have stripped away universalism so that aesthetic judgments must be grounded in specific histories and cultures. See the critique of Anglo-American evaluations of Filipino literature in Oscar Peñaranda, Serafin Syquia, and Sam Tagatac, "An Introduction to Filipino-American Literature," in Aiiieeeee! An Anthology of Asian-American Writers, ed. Frank Chin et al. (Washington: Howard University Press, 1974): l. [⤒]

- Oscar V. Campomanes, "Filipinos in the United States and Their Literature of Exile," in Reading the Literatures of Asian America, ed. Shirley Geok-lin Lim and Amy Ling (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992), 50, 54-55. [⤒]

- Antonio T. Tiongson Jr., "Reflections on the Trajectory of Filipino/a American Studies: Interview with Rick Bonus," in Positively No Filipinos Allowed: Building Communities and Discourse, ed. Antonio T. Tiongson Jr., Edgardo V. Gutierrez, and Ricardo V. Gutierrez (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006), 166. [⤒]

- Yến Lê Espiritu, Asian American Panethnicity: Bridging Institutions and Identities (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992), 25 [⤒]

- Cathy J. Schlund-Vials, War, Genocide, and Justice: Cambodian American Memory Work (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012); Jonathan H. X. Lee and Mary Thi Pham, "Pedagogy for Healing and Justice through Cambodian American Literature," in Critical Pedagogy and Global Literature, ed. Masood Ashraf Raja, Hillary Stringer, and Zach VandeZande (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 97-111. [⤒]

- E. San Juan Jr., The Philippine Temptation: Dialectics of Philippines-U.S. Literary Relations (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 89-90. [⤒]

- Antonio T. Tiongson Jr., "Introduction: Critical Considerations," in Positively No Filipinos Allowed: Building Communities and Discourse, ed. Antonio T. Tiongson Jr., Edgardo V. Gutierrez, and Ricardo V. Gutierrez (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006), 3. [⤒]

- Martin F. Manalansan IV and Augusto F. Espiritu, "The Field: Dialogues, Visions, Tensions, and Aspirations," in Filipino Studies: Palimpsests of Nation and Diaspora, ed. Martin F. Manalansan IV and Augusto F. Espiritu (New York: New York University Press, 2016), 1. [⤒]

- Kandice Chuh, Imagine Otherwise: On Asian Americanist Critique (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 31, 56-57, 9. [⤒]

- Mark Chiang argues that, by rejecting a referent for the term Asian American and any positivist knowledge about Asian Americans, Chuh's subjectless paradigm precludes empirical study of actual differences, power imbalances, and problems of political representation within the population. Chiang, Cultural Capital, 45, 48. [⤒]

- Tiongson Jr., "Introduction," 4. [⤒]

- Some texts cited were filmic, graphic, or non-English, which did not work with our text mining methods. [⤒]

- As in the metadata analysis above, the figures shown in this section are weighted by the number of scholarly citations, so that, for example, The Woman Warrior is counted dozens of times reflecting its extensive citations. [⤒]

- Before running the model, we used the openNLP package to part-of-speech tag the texts. We retained only non-proper nouns (to eliminate character names which tend to muddle topics), foreign words, and adjectives, and split the texts into 1000-word chunks. In topic modeling, the researcher sets the number of topics the model should find and other parameters. We achieved the most interpretable results with 400 topics and the hyperparameter optimization interval set to every 50 iterations. [⤒]

- See, for example, Shirley Geok-lin Lim, "Feminist and Ethnic Literary Theories in Asian American Literature," Feminist Studies 19, no. 3 (1993): 577. [⤒]

- Helena Grice, Negotiating Identities: An Introduction to Asian American Women's Writing (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002), 1. [⤒]

- Leslie Bow, "Asian American Women's Literature and the Promise of Committed Art," in The Cambridge History of American Women's Literature, ed. Dale M. Bauer (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 563-4. [⤒]