New Filmic Geographies

I first saw Samuel Benchetrit's French film Asphalte (2015) with Korean subtitles at a cinema in Busan, South Korea. I have since returned again and again to the film, and to this viewing experience, to think about global cinema's translation problem.

In one early sequence, a NASA astronaut named John Mackenzie (Michael Pitt) plummets to Earth after his space capsule malfunctions, crash landing on the rooftop of a tenement building in an industrial French suburb. There, after startling two pot-smoking teenagers, he finds refuge in the apartment of Aziza Hamida (Tassadit Mandi), a Frenchwoman of Algerian origin. "My name is John Mackenzie!" he barks in greeting, as though this should mean anything. "Are you a Jehovah's witness?" she returns in French, without missing a beat. It's eventually decided that John will stay with Ms. Hamida until NASA can stage a return celebration for him. First, however, NASA will thoroughly interrogate this "Arabic woman" (as they call Hamida), pressing her about her political allegiances and whether she holds anti-American sentiments.

Asphalte is quixotic and darkly funny. The film explores everyday interactions between unlikely people, such a washed-up film actress and a lonely teenager. The pairing of John Mackenzie and Ms. Hamida literalizes this worlds-colliding dynamic, but it also functions as a metaphor for the outsize and often intrusive presence of English (and the US) in the global cinematic landscape. No matter where in the physical world we find ourselves or what language is being spoken, a US-centric gravitational pull is there, asking that we bend to or accommodate it.

After watching Asphalte in South Korea, I decided to teach it as part of an upcoming composition course structured around the theme of "exchange." I put it on the syllabus and promptly forgot about it — until we arrived at the week on linguistic exchange and I realized that there were no English subtitles for this film anywhere to be found.

The irony of this oversight is not lost on me. I think a lot about language politics, and specifically about English as a problem. I research translation, and I grew up in Quebec, a province that has twice tried to separate from the rest of Canada on the basis of linguistic exceptionalism. And yet, though I'd watched Asphalte in Busan — where it was subtitled in Korean — it never occurred to me that there might not be English subtitles readily available. It's this engrained presumption that I wish to investigate, here, by calling attention to the powerful and often invisible work that subtitles do.

Translation destabilizes "the potent myth that film speaks a universal language that transcends linguistic and cultural difference, existing somehow beyond translation."1 North America, more than anywhere else, embraces this universal language argument. Despite recent inroads made by streaming giants like Netflixto popularize films in languages other than English in North America, the population remains overwhelmingly monolingual.2 Unlike lowbrow pop-cultural phenomena like K-Pop and K-dramas — which boast truly diverse global fanbases and rich fansubbing cultures — Korean film has had to lean more heavily on English (and, implicitly, the US) in its promotional strategies.3 It is telling, for instance, that the state-sponsored Korean Film Archive's YouTube Channel — which boasts a sampling of over 110 classic Korean films from the 1930s on, and which has amassed, as of this writing, over 240 million views — offers subtitles in English only.4 As Hye Seung Chung and David Scott Diffrient argue, "as one of the latest discoveries for Western cinephiles, South Korean films . . . bring cultural cachet, if not huge profits, to Netflix, a company whose target demographic encompasses a wide array of young urbanites with diverse tastes in world cinema."5 Between 2015 and 2020, Netflixinvested over 700 million USD in Korean language content, and their announcement in January 2021 of their intent to establish two production studios in South Korea suggests that Korean content is poised to be even more popular (and profitable to the platform) in the coming years.6

When Bong Joon-ho's Korean language film, Parasite, swept the major categories at the 2020 Academy Awards, his remarks — "once [you] get over the once-inch barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many wonderful films" — seemed, on their face, a rebuke to anglocentrism. But unlike Bong's previous four releases (The Host, Tokyo!, Snowpiercer, Okja), all of which are self-conscious about the problem of English and the reflexive orientation toward the US and its film culture, Parasite's subtitles are distinct in that they westernize Korean cultural references for "ease of viewership."7 This subtitling style — which cannot be disentangled from the film's accolades in the US context — reflects the fluency model that Madhu Kadza argues defines US literary translation culture. The US prefers "accessibility and seamlessness," a translation in which "all the wrinkles that would remind us that it is translation are ironed out."8 This preference stands in contrast to the rest of the world, where, especially in postcolonial contexts, translation is understood to be inherently political, and those politics are often at the center of critique.9

Bong's Okja, though less critically and commercially successful than Parasite, offers a more useful model for thinking through how translation shapes the flows of global cinema. Bong opted to release Okja via Netflix's streaming service, becoming one of the first multi-million-dollar productions to do so. This partnership made Okja accessible to audiences in 140 countries and transformed film consumption and production in South Korea, where domestic theatrical releases comprise the bulk of the film industry's revenue and supporting homegrown cinema is seen as an act of nationalist pride.10 Following Okja's release, South Korean Netflix users more than doubled, from 97,922 subscribers to 202,587 in one week.11 Bong's Netflix partnership fostered a more equitable film environment in South Korea, enabling Okja's audience to choose how to view the film. It also contributed to one of Netflix's core missions: to "subtly expose monolingual viewers to new languages and cultures."12

The power dynamics of language also animate Okja at the level of plot. The film tells the story of the titular creature, one of twenty-six "super pigs" genetically engineered by the US agro-conglomerate Mirando. Once crowned "best super pig" by Mirando, Okja is taken from her home in South Korea to a lab in New York City, where she will undergo a battery of tests before being sent to the slaughterhouse. The film follows the actions of two parties — the activists of the Animal Liberation Front (ALF); and Mija (An So-hyeon), the young Korean girl who raised Okja — to save the pig from slaughter, with an eye to the different ethical motivations that undergird their efforts. The question of translation first emerges in an exchange between Mija and K (Steven Yeun). ALF activists have kidnapped Okja from Mirando headquarters in Seoul and are hoping to send her to the lab in New York with a secret camera in her ear to expose the company's abuses. But this plan threatens to fall through when Mija hijacks their escape truck and begs them to set Okja free. Listening to Mija's words through K, the group's interpreter, ALF leader Jay (Paul Dano) implores Mija to let them go through with their plan, acknowledging that they will not continue without her consent, per the ethical credo of the organization. But when K hears Mija's response — "I want to go back to the mountains with Okja" — he lies and tells the group that she agrees. Though Mija immediately senses that something is amiss, she can only look on as the activists set her and Okja on a truck, bound for uncertain futures in New York City.

K's is a layered lie, which will come back to haunt him. Though his mistranslation facilitates the successful completion of ALF's mission, K's transgression — to which he ultimately confesses — leads to his expulsion from the organization. Adding injury to insult, he is viciously beaten by Jay, who tells him that "translation is sacred" and that his lie dishonors the legacy of ALF activists. This scene underscores a deeply-rooted presumption of fidelity. The activists, after all, did not raise an objection to K's translation, even when it provoked a distressed reaction from Mija. Jay beating K further suggests that there is a kind of violence that attends translation, registered through the spectacle of a purportedly nonviolent activist brutally disciplining a translator. That K confesses to his mistranslation is a reminder of our tendency to overlook what Lawrence Venuti calls "the greatest scandal" of translation: namely, the "asymmetries, inequities, relations of domination and dependence [that] exist in every act of translating, of putting the translated in service of the translating culture."13

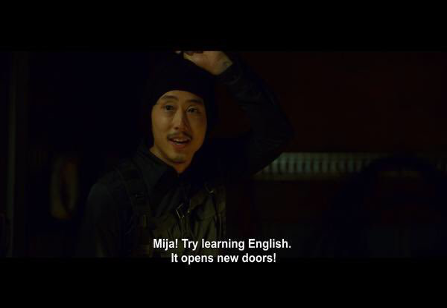

Translation in Okja is tied to K's (and actor Steven Yeun's) identity as Korean-American. If the film's translational politics make translation visible to an anglophone audience whose relationship to language is often apolitical, they also appeal to a multilingual, or other-than-English, viewership with their critique. Consider K's parting words to Mija after his translational lie. While the English subtitle to this line (fig 1) reads one way ("Mija! Try learning English! It opens new doors!"), Korean speakers hear a humorous, and intimate, moment of introduction across cultural lines, with K revealing his real (Korean) name to the girl ("Mija! Also, my name is Gu Seonbeom!") (fig.2). But it is only bilingual speakers who recognize the payoff of this scene: what initially appears as a patronizing rebuke to learn English — a common refrain in Korea and in Asian-America — is in fact a sly confirmation of the opposite: to know languages other than English opens doors, too.

My point here is not that one must "master" a language in order to be in on the joke at the heart of the film — mastery, after all, having roots in the exploitative structures Okja endeavors to critique. Instead, I suggest, Okja urges us to approach learning other languages and cultures with sincerity and a willingness to make mistakes. Jay's apology to Mija via bilingual cue cards toward the end of the film is an example of this kind of earnestness; it is also, I venture, what makes Yeun's performance as K, a character caught between different linguistic and cultural worlds, so compelling. Since his departure from the massively popular AMC series The Walking Dead in 2016, Yeun has increasingly turned to roles set in or about Korea, including a Korean-language performance as Ben in Lee Chang-dong's critically acclaimed film Burning. Whereas K is a bumbling Korean speaker (Yeun admits that he exaggerated his pronunciation for the film), Ben speaks in fluid, sophisticated prose that belies the amount of work Yeun put into the role.14 His most recent Korean language effort, in Korean-American director Lee Isaac Chung's Minari (2020), similarly illustrates the range of intergenerational and cross-cultural connections made possible by work that centers translation.

That the Golden Globes classed Minari as a foreign language film — despite its setting in rural Arkansas and reviews that trumpeted its "universality" — speaks to the enduring rigidity around what counts as an "American" feature.15 But it also suggests that these categories are increasingly becoming obsolete, and that artistic producers and audiences alike are drawn to works that offer new ways of communing with each other across languages and cultures.

It is this potential — for multiple, divergent points of connection — that Okja highlights. While one might read the reemergence of K at the close of the film, arm newly-outfitted with a tattoo of Jay's chastising words, as an act repentance that reinscribes the importance of translational fidelity in service of an anglophone majority, a closer look at the tattoo's wording (fig.3) proves instructive. The tattoo is a subtle mistranslation of Jay's language, one that moves away from a singular, moralizing rightness ("translation is sacred") to a more capacious, plural vision of what translation can do ("translations are sacred").

When I taught Asphalte, I subtitled the film myself, but opted not to tell my students that I'd done so. Our discussions were generative, but this decision haunted me. It felt hypocritical. My scholarship stresses the importance of making translation work visible, yet here I had taken pains to hide my work and the biases built into it. So when I had occasion to teach the film again, I was transparent about the process. I was delighted to find that the conversations that emanated out of this — which ranged in topic from the dominance of English and forms of cultural translation to individual accounts of code-switching and dialectical speech — were so much richer and varied than they had been the first time around. It was fitting, too, that when I taught the course a second time, the theme had evolved from "exchange" to "encounter" — from a term that borders on the transactional and extractive to one that is more open, curious, and engaged.

Subtitles "offer a way into worlds outside of ourselves. They are a unique and complex formal apparatus that allows the viewer an astounding degree of access and interaction. [They] embed us."16 Imagine the worlds that emerge when we proceed from an acknowledgement of difference, and make that the point of encounter.

Claire Gullander-Drolet is a postdoctoral fellow in the Society of Fellows for the Humanities at the University of Hong Kong. She writes about and researches translation, transpacific cultural production, and the environment.

References

- Tessa Dwyer, Speaking in Subtitles: Revaluing Screen Translation (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 2017), 3.[⤒]

- See Jay Mathews, "Half the World is Bilingual. What's Our Problem?", The Washington Post, April 25, 2019.[⤒]

- For an interesting account of K-drama's global fansubbing culture and the general elision of translation work in Korean cultural productions, see Amanda Halprin, "The Voices of Viki: Considering Fansubbers as Linguistic Gatekeepers." Flow Journal, July 2, 2018. [⤒]

- Korean Film Archive Youtube Channel[⤒]

- Hye Seung Chung and David Scott Diffrient, Movie Migrations: Transnational Genre Flows and South Korean Cinema (New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 2015): 243.[⤒]

- "Expanding Our Presence in Korea: Netflix Welcomes the New Year With Two New Production Facilities." [⤒]

- For an account of the kind of flattening the English subtitles in Parasite do, see Su Cho's "Subtitles Can't Capture the Full Class Critique in Parasite," Medium, February 3rd, 2020. I would add to the instances they describe here the way the subtitles inexplicably substitute the names of elite Korean universities (Seoul National) for western ones (Oxford). For an exploration of the way that Bong negotiates the influence of Hollywood in his earlier work, see Christina Klein, "Why American Studies Needs to Pay Attention to Korean Cinema, or, Transnational Genres in the Films of Bong Joon-ho." American Quarterly 60, no. 4 (2008): 871-898. For more on Bong's translation politics, see Claire Gullander-Drolet, "Bong Joon-ho's Eternal Engine: Translation, Memory, and Ecological Collapse in Snowpiercer (2013)," Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities 7, no. 1 (Winter 2019): 6-21.[⤒]

- Madhu H. Kadza, "Editor's Note," in Kitchen Table Translation: An Asteri(x) Anthology (Pittsburgh, Blue Sketch Press, 2017): 14.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Nikki J.Y Lee, "Localized Globalization and a Monster National: The Host and the South Korean Film Industry." Cinema Journal 50, no. 3, (2011): 50-51.[⤒]

- Jun-gyeong Geum, "The Okja Effect: Netflix Users Increase Twofold." [in Korean] Media Korea, July 18th, 2017. [⤒]

- Zimena Larkin, "How Netflix's increasing use of foreign language content is helping to fight xenophobia," The Independent, April 14th, 2018.[⤒]

- Lawrence Venuti, The Scandals of Translation: Towards an Ethic of Difference (Routledge, 1998): 4.[⤒]

- Kristen Yoonsoo Kim, "Steven Yeun's Smile Will Fool You," The Ringer, October 23rd, 2018. [⤒]

- For an important critique of this universal reading of the film, see Jane Hu, "The Specificity of Minari," The Ringer, February 17th, 2021.[⤒]

- Atom Egoyan and Ian Balfour, "Introduction," in Subtitles: On the Foreignness of Film (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2004): 30.[⤒]