New Filmic Geographies

To see the world in a grain of sand

William Blake

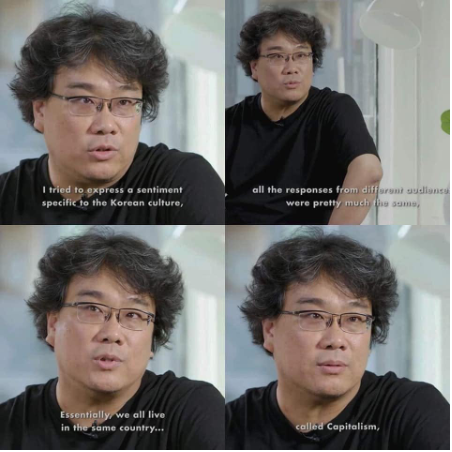

During Oscars season 2020, the internet was abuzz with a meme of Bong Joon Ho reflecting on the widespread positive reception of Parasite. Bong theorized that his film resonated with viewers around the world because "we all live in the same country called Capitalism."

It was a viral moment, even if the sentiment was unoriginal. In 2005, Jia Zhangke, meditating on his film The World (2004), said, "People are the same everywhere. It doesn't matter if you live in Beijing, Paris, Toronto, or Africa; you are facing the same fundamental challenges."1

If we all live in the same country and if people are the same everywhere, what is the role of international film? Taking seriously Suzanne Enzerink's provocation to imagine "transnational cinema [as] the aesthetic expression of an increasingly globalized world, where national film cultures have been eroded or recoded by circuits and flows (of capital, of shooting locations, actors, distribution),"2 what, nonetheless, do we think we will be given to see? If a new generation of transnational filmmakers might provide us with our "new filmic geographies," where do we hope that these new filmic geographies will take us, and why? A cohort of contemporary filmmakers from Bong Joon Ho to Mati Diop, Jia Zhangke to Boots Riley is making films set variously in Seoul, Dakar, Beijing, and Oakland, and they all share the same goal of exposing the specter of class inequality and attending to the ills of capitalism. Implicit in Bong's statement is the suggestion that capitalism makes geography irrelevant. But if these films, international though they are, are to be cherished for their eviscerating and necessary criticism of "the same country of Capitalism," what is the importance of our new filmic geographies?

I want to consider this question through two films I've seen in the past year, my intimate attachment to them itself a consequence of the displacement and mobility of labor in a neoliberal world. Yeo Siew Hua's hypnotic A Land Imagined (2018) is set in Singapore and follows an insomniac detective charged to solve the disappearance of a Chinese construction worker. Jia's The World accompanies a Chinese couple who have moved from their village to Beijing in search of work.

Yeo's film is interspersed with long scenes at a work site. Piles of gravel are demolished to make new piles. Ultimately, we learn that we are watching a land reclamation site, where Singapore uses earth from elsewhere to extend its shoreline. Viewed this way, modern Singapore is a kind of modernist assemblage, comprised of actual material from other nations. Conversely, The World is set in World Park, a Baudrillardian dreamscape made up of replicas of architectural wonders from across the world: diminished models of the Vatican, the leaning tower of Pisa, an Eiffel Tower standing at a third of the height of the original. World Park's punchy and paradoxical tagline — "Travel the world without leaving Beijing!" — stretches the tension between the global and the local, taking the idea of "glocalization" to its reductio ad absurdum.3 In one film: the expansion of shoreline, countries conglomerated into a single undifferentiated land mass. In another: the erosion of experience, the world cut down to size. In challenging us to reckon with what exactly makes up a nation (fungible soil, replicable icons), both films explode our notions of the local and the transnational.

Two years ago, before I left Singapore for my current job, I had its outline tattooed on my wrist, stamping my country onto my pulse to remind me to keep my finger on hers. But my tattoo is already inaccurate. The outline I have is too craggy at parts — too natural — tracing an outline of an older map. Today, the southwestern tip of the island is unnaturally angular and straight, smooth and comb-toothed, making the rhomboid island look like a crab with a bionic claw. I trace Singapore today, her outline will change tomorrow. The tides never erode her ersatz shores.

Singapore is derived from the anglicized version of Singapura, which means Lion City in Malay. This is in turn transliterated into Chinese as 新加坡 (xīn jiā pō). 新 means new, 加 means to add, and 坡 refers to a bank, or shore, or a hill. Taken together and directly translated, the chosen Chinese characters for Singapore's transformed and transliterated name mean: newly added shore — in other words, reclaimed land. Did Singapore's name always anticipate the country's future endeavors, always underscore and betray its dream of expansion? Perhaps the literal and the littoral, in Singapore, have always been bound together in this way.

Unsurprisingly, then, A Land Imagined meditates on the tensions between the national and the transnational. The title expresses its investment in fungibility and fantasy, even the fantasy of fungibility. Fungibility is defined as the interchangeability of materials and implies equal value between assets.4 A Land Imagined is given in the Chinese as 幻土, which means "imagined land" or "dreaming land" or "dreaming of land." The homonymic nature of Chinese lends itself to puns, and so 幻土 also puns with 换土, which means exchanging land, or swapping land — in other words, land reclamation: Singapore is increasingly a land imagined. Since independence in 1965, Singapore has increased its land mass by almost 22%,5 6 buying land from neighboring countries for its expansion project, destroying communities and ecosystems elsewhere.7 The scenes showing the movement of gravel display not a closed innocuous system, but allegorize a zero-sum game in which one country grows bigger by cannibalizing those around it. Singapore, in fact, even aims to game this process, employing Dutch poldering and dam engineering technology to reclaim more land for the same amount of soil.8 9 10

In A Land Imagined, two characters, Wang and Mindy, hang out on the beach at night and muse about Singapore's shoreline. Wang tells Mindy, "The sand here is imported from Malaysia . . . Other reclaimed parts of Singapore are from Indonesia, and Vietnam. I heard that Cambodia supplies our construction site . . . Some say it's bought off the black market." She responds excitedly, "Doesn't that mean we're no longer in Singapore? We're actually lying in Malaysia!" He smiles and tell her, "next time, I can take you to other reclaimed areas to see . . . the world!"

Never was Blake's romantic invitation to see the world in a grain of sand more literal, or more tragic. Wang's offer for faux touristic pursuits is full of pathos: the world, for our protagonists, is tragically shrunk to the limits of Singapore — literally: many low-wage laborers are trapped in Singapore, working to pay off the debts they took on to get there, with their passports withheld by employers. The film drives this point home with irony: the passports are locked in a cabinet labelled "first aid."

When it comes to the fungible soil (which also serves as a metaphor for the replaceable foreign labor in the film), there isn't even the illusion of difference; this is allegorized by the many scenes of droning machinery moving gravel almost senselessly from one pile to another. Wherever they go, Wang and Mindy are still always in the milieu of an uncaring and unequal Singapore, awful and expanding at every moment. As if offering a bleak response to this reflection, when asked how long this land reclamation will go on, the construction supervisor says, "We've never stopped reclaiming land. We'll reclaim for as long as we can." Echoing Bong's revelation about national difference or lack thereof, Singapore's financial ability to capture land reveals the same thing: capitalism reduces the world to an undifferentiated mass.

Singapore belabors the point that it has no natural resources, that its only resource is its people. But as a global financial hub, its main resource is in fact capital. And as opposed to its people, it is capital that is put on brash display as a visual shorthand for Singapore on the world stage. Not images of a diverse and multicultural nation populate the global imagination, but pictures of the twinkling skyline of the financial district, artificial skytrees, and flower domes catering to tourists. It's not Singapore and Singaporean stories that are interesting to global audiences, but wealth. Crazy Rich Asians made $238.5 million in the box office. Ilo Ilo a 2013 film about a Singaporean family that won Singaporean director Anthony Chen the prestigious Camera D'Or award at Cannes made only approximately $3 million. Much of Netflix's recent content about Singapore traffics in prosperity porn for which its global viewership is hungry. But this content isn't created by Singaporeans. Singapore Social, a docuseries capitalizing off the success of Crazy Rich Asians,is produced by a UK-based company. The more recent Bling Empire is more of the same.

Against a country like Singapore, which is now all too visible, reduced to its wealth in the global imagination, China looms large, but also yet unknown. For an economy that is set to overtake America's in the next decade, few films in the West offer considered portraits of modern China. Popular films likeZhang Yimou's Great Wall (2016) and Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon (2000) either caricature history or reduce the country to stereotypical kung fu masters.In contrast, Zhang Yimou's historical realist films such as To Live (1994) and Coming Home (2004) about China's Cultural Revolution rarely make the big screen in the US. The names of certain fifth generation Chinese filmmakers circulate widely because their films are known for being banned in China, but even globally, their films are rarely seen beyond the arthouse film festival circuit. These films are difficult to source, if one even knows to seek them out, often ensconced in the corners of the Criterion Collection, behind paywalls, and, in some cases, firewalls. At the moment of writing, Chen Kaige's Palme D'Or-winning Farewell My Concubine (1993), the only Chinese-language film to win the prestigious award, is unavailable to be streamed on any platform in the US.

***

Martin Heidegger and Jean Baudrillard argue that technology changed our ontology in the twentieth century. Heidegger writes that we have come to experience the world "conceived and grasped as a picture."11 Jia's The World showcases Heideggerian ontology to undercut it. It also offers an extended meditation on the truncated attention span of our contemporary condition: the slogan for World Park reads, "Give me a day; I'll give you the world!" Set in World Park Beijing, which opened its doors in 1993 and features replicas of architectural icons from across the world, The World is a Baudrillardian critique, invested in demonstrating the crumbling effects of the simulacra, of grasping the world as a picture:"China looks like a modern country, but if you look underneath the surface, it isn't. Reality has become a kind of illusion. Reality is a mess in China."12

Baudrillard's Simulacra and Simulation opens with a meditation on the Borges fable "in which the cartographers of the Empire draw up a map so detailed that it ends up covering the territory exactly." Borges's cartographer's vision materializes, half-baked, in Beijing's World Park, collapsing into the bathetic miniaturization of grandiose architectural feats. The film enacts this bathos for its audience in a slow unraveling. The first structure we see is the Eiffel Tower, which, at a third of the height of the original, still retains something of its grandiosity, maintaining the illusion that it is a like-enough replica. But this falls apart pathetically and comically as we see the formidable Vatican City shrunk to the size of a playground.

We see the cheap production quality in close up shots. The enterprise of holding the world in the palm of one's hand is thus rendered undesirable because kind of lame. This bathos is echoed in pathos: the park is meant for and serviced by the majority of Chinese people who cannot afford to travel. When asked by a friend if she's ever been on a plane, one character replies, "I don't even know anyone who has been on a plane." Jia's observation that "most individuals in China are living in an illusory world" is literalized in the scene where two characters sit in the cockpit of a model plane — the closest either of them will ever get to flying.13

World Park's tagline, "Travel the world without leaving Beijing!" unintentionally reveals the truth about China's phenomenal economic growth. As Jia explains, "With The World, I want to show the conflicts between the superficial idea of modernization and the deeper reality of a much deeper backwardness.... You can walk from the Eiffel Tower to the Pyramids with ease. You can visit different countries without a passport or a visa. It gives the impression that the whole world has become a global village. A lot of Chinese people think that way nowadays — they believe that China has really become a part of the international community. But that's not really a true reflection of the lives of everyday people in China."14 Under Jia's masterful hand, World Park not only attempts to imitate the world — its shoddy construction laying bare the futility of the enterprise — but endeavors to put the world inside Beijing, consuming and erasing it for its visitors, tempering desire and quelling the appetite for the outside.

The Chinese characters for China 中 国 mean middle kingdom, putting China at the center of the world. From the center of the world, everything else is peripheral. In a year where the global economy suffered unprecedented losses, and national borders were closed or tightened for most countries, enforcing by default more local and grounded economies, China was the only major economy to report an expansion — of 2.3% — in 2020,15 with predictions that it will overtake the US as the largest economy in the world sooner than previously believed. If these reports demonstrate the extent to which China does not need the world, The World offers us a glimpse of what that world may yet look like for many of its citizens who will never leave the country.

***

In the face of an oppressive irreality, both Yeo and Jia rely on a documentary approach. Yeo explains that foreign workers "aren't always afforded time and space in society. It's precisely this lack of visibility that compelled us to cast as many migrant workers as possible, to show actual scenes of how they lived and work, which also gave rise to the documentary approach to the film."16 Jia is also a documentary filmmaker and became fascinated with World Park because his partner, actress Zhao Tao, worked at a similar park, Window of the World, in Shenzhen, before she was accepted into the Beijing Dance Academy. The World was shot onsite and the actors play versions of themselves: Zhao Tao plays Zhao Tao, Cheng Taisheng plays Cheng Taisheng, and so on.

In a year of pandemic lockdown and restricted travel, I was, unsurprisingly, taken by these two films: one about my home country, and another titled The World. But both resolved nothing for me, providing neither comfort nor escape. Instead they produced a heightened claustrophobia that I find myself straining against. It's not Singapore or Beijing that generates claustrophobia, but capitalism.

In Parasite, Bong produced a searing commentary on inequality — one that is powerful for its universal appeal, even as it pointedly tackles the specific issues of South Korea's present moment: the helicopter parent and the overstimulated child, smothered and glutted with art therapy lessons and ramdon alike; the wealthy Park family's house is the one that gets a lot of media attention, but in fact the banjiha (basement apartment) that the Kims live in is the more significant piece of architecture — both politically and to the narrative. Thousands of young people live in such banjihas in Seoul to save money while they work to eke out a living. In fact, the banjihas are an enduring monument to an important moment in Korean history: in 1970, in response to rising tensions with North Korea, the South Korean government updated building codes to require basement bunkers for new apartment buildings.17

Parasite won big at the 2020 Oscars (one of the last major events of 2020 before lockdown), amid rousing applause and standing ovations from the (mostly white) wealthy celebrity class. It is laughably ironic how much the rich love Parasite.In the weeks immediately following, as America and the rest of the world hunkered down, those same celebrities made repeated gaffes in churning out tone-deaf social media content featuring themselves in their Beverly Hills mansions — many of which share the burnished minimalist aesthetic of the Parks's house. More Parasite memes proliferated in response highlighting the out-of-touchness of celebrity activism, and indeed, of the wealthy in general.

It's not enough that a contemporary Korean film director makes a film that feels universal. If our new filmic geographies are to make visible the circuits of an increasingly globalized world, not only do they have to bring us to different locales, they also have to help us to imagine a different world than the one called Capitalism. But audiences have a responsibility too in consuming international films: we have to bring an excavating curiosity to the films we watch; we have to not miss the trees for the forest, to resist becoming blind to geographically specific problems for a vision that is only in service of a universal critique. Films like Parasite should be cherished for their transferability and transnational appeal, but that should not make a blind spot of their local critique.

Jerrine Tan (@jerrinetanew) was born and raised in Singapore. She has a PhD in English from Brown University and currently teaches Global Anglophone Literature in the English department at Mount Holyoke College. Her essays have been featured in WIRED, Lit Hub, Asian American Writers' Workshop, and are forthcoming in Modern Fiction Studies and The Cambridge Companion to Kazuo Ishiguro.

References

- Shih A. Jia Zhangke: life and times beyond The World. CineAction 68 (2006): 53. [⤒]

- New Filmic Geographies CFP[⤒]

- A term popularized by sociologist Roland Robertson in the Harvard Business Review (1980), referring to the marketing strategy of adapting local and international products to local contexts. The concept first originated from Japan. In a particularly comedic moment in the film, a character points to a sight in the park (offscreen), exclaiming that it looks like a dam that had been built in their village. As the camera pans to the object he is pointing at, it's revealed to be a miniature London Bridge.[⤒]

- See Sadiya Hartman's Scenes of Subjection. I borrow from her conception of fungibility in a different context. While I read the indentured laborer as a kind of modern-day slave figure in A Land Imagined, I do not mean to equate it to the experience of the black slave in America.[⤒]

- William Jamieson. "In Conquering the Sea, Singapore Erases Its History." Failed Architecture, March 12, 2018.[⤒]

- "Such Quantities of Sand" The Economist. February 26, 2015. [⤒]

- Kalyanee Mam. "When Your Land is Stolen From Beneath Your Feet," The Atlantic, March 11, 2019. [⤒]

- Yeo Sam Jo, "Dutch experts give advice on Tekong land reclamation," Straits Times, November 17, 2016.[⤒]

- Housing & Development Board, "Polder Development at Pulau Tekong," YouTube, November 16, 2016.[⤒]

- The film was a collaboration between Singapore, France, and the Netherlands.[⤒]

- See Heidegger "The Age of the World Picture"[⤒]

- Richard James Hayis, "Illusory Worlds: An Interview with Jia Zhangke," Cineaste (Fall 2005): 58-59. [⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Jonathan Cheng, "China Is the Only Major Economy to Report Economic Growth for 2020," The Wall Street Journal, January, 18 2021. [⤒]

- Sihan Tan, Interview with Yeo Siew Hua, Bomb Magazine, May 24, 2019.[⤒]

- Julie Yoon, "Parasite: The real people living in Seoul's basement apartments," BBC Korea, February 10, 2020.[⤒]